Abstract

An 18-year-old woman was referred with late sequelae of chloroquine-induced Steven–Johnson syndrome. At the time of presentation, the symblepharon was involving the upper lids to almost the whole of the cornea, and part of the lower bulbar conjunctiva with the lower lid bilaterally. Other ocular examinations were not possible due to the symblepharon. B-scan ultrasonography revealed acoustically clear vitreous, normal chorioretinal thickness, and normal optic nerve head, with an attached retina. Conjunctivo-corneal adhesion released by superficial lamellar dissection of the cornea. Ocular surface reconstruction was carried out with a buccal mucous membrane. A bandage contact lens was placed over the cornea followed by the symblepharon ring to prevent further adhesion. The mucosal graft was well taken up along with corneal re-epithelization. Best corrected visual acuity of 20/120 in both sides after 1 month and 20/80 after 3 months was achieved and maintained till the 2.5-year follow-up.

Keywords: Ocular surface reconstruction, Steven–Johnson syndrome, superficial keratectomy

Steven–Johnson syndrome (SJS) is known to be caused by sensitivity to drugs, variety of infection, certain vaccines, toxins, deep X-ray therapy, malignancy, food, and pregnancy.[1] The role of drugs is said to be the most important. The commonest causative drug has been reported to be long-acting sulfonamides[1] and among the antimalarial drugs, chloroquine is said to be the most notorious causative agent.[2]

The treatment aims at the restoration of the anatomical structures and physiologic properties of the ocular surface.[3] In chronic phase, autologous or allogenic limboconjunctival graft are best used for transplantation. However, due to unavailability of the conjunctival tissue for transplantation in cases of bilateral involvement, another autologous graft, i.e., mucosal or amniotic membrane is used.

Case Report

An 18-year-old female patient presented with inability to open both eyes for 6 weeks. She had a history of fever from malaria 2 months back for which she was treated with oral chloroquin phosphate 500 mg. She developed erythematous papular eruptions on the trunk, mouth, and limbs along with pain, redness, and watering from both eyes 5 days after taking the medication followed by gross diminution of vision and inability to open her eyes. She was diagnosed to be a case of SJS and was treated conservatively elsewhere. The erythematous lesions resolved completely at 4 weeks with medications, but she was unable to open her eyes and she was referred to us for further evaluation and management. At the time of presentation, her visual acuity was positive perception of light in both eyes, with both the upper lids adhered to almost the whole of the cornea, and part of the lower bulbar conjunctiva with the lower lid [Fig. 1]. Other ocular examination was not possible due to adhesion. Intraocular pressure was found digitally normal. B-scan ultrasonography (USG) revealed acoustically clear vitreous, normal chorioretinal thickness, and normal optic nerve head with an attached retina.

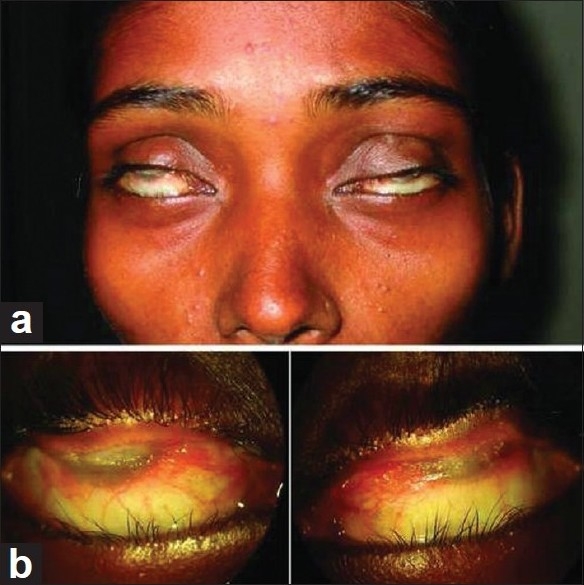

Figure 1.

Preoperative view: gross appearance (a). Close-up view shows the cornea and upper tarsal conjunctiva being totally adhered in both eyes (b)

Routine blood examination, blood glucose, and serum urea and creatinine levels were within normal limits. Physician evaluation was done by meticulous history taking, clinical examinations, and key laboratory examinations to exclude other blistering skin diseases such as pemphigus vulgaris, bullous pemphigoid, mucocutaneous diseases like Behçet's syndrome and Reiter's syndrome, and vasculitis like systemic lupus erythematosus. The patient was taken up for surgery and superficial lamellar dissection of the cornea was done to separate the conjunctivocorneal adhesion, followed by release of symblepharon between palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva. The inspection of the limbus revealed areas of scattered peripheral corneal neovascularization affecting less than 3 clock hours in both eyes, which implied the areas of limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) of the corresponding areas. Rest of the limbus appeared clinically healthy. The buccal mucous membrane was harvested after injecting 2% xylocaine with adrenaline (1 in 200,000) into the proposed site and the graft was removed from below moving upward. After harvesting, the extra fat was removed from the graft. A mucous membrane graft (MMG) of size 27 × 8 mm (right eye) and 26 × 8 mm (left eye) was placed over the raw area of superior bulbar conjunctiva and secured with interrupted stitches using 8-0 vicryl. The lower bulbar conjunctiva was covered by a MMG of size 15 × 7 mm (right eye) and 14 × 7 mm (left eye) and sutured in a similar fashion. A bandage contact lens (BCL) was placed over the cornea. This was followed by the placement of a symblepharon ring to prevent the recurrence of symblepharon and a temporary tarsorrhaphy was placed in both eyes to achieve some pressure effect on the MMG by the symblepharon ring [Fig. 2]. The patient was given a systemic antibiotic (cephalexin 500 mg three times a day for 5 days) and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (Ibugesic 100 mg, –paracetamol 500 mg, combination twice daily after meal for 4 days) along with a topical antibiotic steroid (Gatiflxaciin with dexamethasone, one drop six times a day for 1 month) combination, and a tear substitute (Carboymethylcellulose) was prescribed for six times a day for 6 months.

Figure 2.

Early post-operative view (seventh day): – gross appearance (a). Close-up view of both eyes with the bandage contact lens and symblepharon ring seen in situ (b)

The re-epithelialization of the corneal epithelium was completed by in 10 days. Temporary tarsorrhaphy was removed after 2 weeks and both the BCL and the symblepharon ring was removed at 4 weeks. Except few sectors of peripheral corneal vascularization, no other sequelae were observed postoperatively. The patient showed remarkable recovery. Best corrected visual acuity of 20/120 in both sides after 1 month and 20/80 after 3 months [Fig. 3] was achieved and maintained till the 2.5-year follow-up without any other sequelae.

Figure 3.

Postoperative view (3 months): gross appearance (a). Close-up view showing well reconstruction in the inferior fornix in both eyes (b)

Discussion

The exact etiology of SJS is not known and the understanding of the etiopathogenesis and management protocol of ocular adnexal complication of SJS has been limited so far. Often, patients of SJS are treated by a physician or dermatologist in early phases and later referred to an eye care center. Patients often consult an ophthalmologist with severe ocular sequelae only after the resolution of skin lesions, as in our case.

The acute stage of the SJS is characaterized by bilateral catarrhal and membranous conjunctivitis. During the chronic stage of the disease, most patients have various alterations of the ocular surface, such as symblepaharon, entropion, trichiasis, dry eye, limbal cell deficiency, conjunctival inflammation and corneal neovascularization.[4,5] The major aim of treatment in late phases of SJS is ocular surface reconstruction to correct cicatricial sequalae and chronic inflammation.[3] Management option in late cases is a challenge and is often frustrating, because of the combination of various alterations in surface milieu causing severe dryness and surface inflammation leading to treatment failure.

Several surgical approaches for the reconstruction of the ocular surface in cicatricial disorders with or without significant LSCD have been tried with encouraging results.[6] To reconstruct and maintain the ocular surface, a healthy conjunctiva when available, is the ideal material for grafting.[7] A full-thickness oral MMG is the simplest graft[7] to use if a conjunctiva is not available. It is preferred over split-thickness mucosal grafts as it contracts less in comparison, though a split-thickness graft is more preferable from the cosmesis point of view because of its lesser bulk and pinky appearance[7] However, amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT) is an accepted approach to the surgical management of chronic symblephera because of the unique properties of the membrane,[8] especially in cases with significant LSCD.[9] It can be combined with limbal transplantation and with an adjunctive antimetabolite. However, in cases with an adequate reserve of limbal stem cells, mucosal tissue transplantation achieves equally good results[10] as seen in our case. Mucosal tissue transplantation can be considered in situations where cost and inadequate infrastructure are concerned. Our case had a partial LSCD which was scattered and amounting to 3–4 clock hours in each eye. As such the corneal re-epitheliazation was satisfactory after the procedure. In cases of severe bilateral LSCD, an additional procedure of stem cell harvesting and ex vivo culture would have been required. The ultimate aim of treatment of the chronic phase of ocular surface disorders like SJS is restoration of the anatomical structures and physiologic properties of the ocular surface.

References

- 1.Bianchine JR, Macareg PV, Lasang LI, Azarnoff DL, Brunk SF, Hvidberg EF, et al. Drugs as Histological factors in SJ Syndrome. Am J Med. 1968;44:390–405. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(68)90110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beedimoni RS, Rambhimaiah S. Oral chloroquine-induced Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Indian J Pharmacol. 2004;36:101. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimazaki J, Yang H-Y, Tsubota K. Amniotic membrane transplantation for ocular surface reconstruction in patients with chemical and thermal burns. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:2068–76. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart MG, Duncan NO 3rd, Franklin DJ, Friedman EM, Sulek M. Head and neck manifestations of erythema multiforme in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111:236–42. doi: 10.1177/01945998941113P112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsubota K, Satake Y, Kaido M, Shinozaki N, Shimmura S, Bissen-Miyajima H, et al. Treatment of severe ocular surface disorders with corneal epithelial stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1697–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906033402201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomes JA, Santos MS, Ventura ẦS, Donato WB, Cunha MC, Höfling-Lima AL. Amniotic membrane with living related corneal Limbal/Conjunctival Allograft for Ocular Surface Reconstruction in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1369–74. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.10.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson H, Collin J. Mucous Membrane Grafting. In: Geerling G, Brewitt H, editors. Surgery for the Dry Eye. Vol. 41. Basel Karger: Dev Ophthalmol; 2008. pp. 230–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimazaki J, Shinozaki N, Tsubota K. Transplantation of amniotic membrane and limbal autograft for patients with recurrent pterygium associated with symblepharon. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:235–40. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azuara-Blanco A, Pillai CT, Dua HS. Amniotic membrane transplantation for ocular surface reconstruction. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:399–402. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.4.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manner GE, Mathers WD, Wofley DE, Martinez JA. Hard palate mucosa graft in Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118:786–91. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72559-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]