Abstract

This retrospective, interventional case series analyses treatment outcomes in eyes with choroidal neovascularization (CNV) secondary to pathological myopia, managed with photodynamic therapy, (PDT), (Group 1, N = 11), PDT and intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide (4 mg/0.1ml) (Group 2, N = 3), PDT and intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) bevacizumab 1.25 mg/0.05 ml, ranibizumab 0.5 mg/0.05 ml and reduced-fluence PDT and intravitreal ranibizumab 0.5 mg/0.05 ml (Group 3, N=12). All the patients underwent PDT. Intravitreal injections were repeated as required. SPSS 14 software was used to evaluate the data. Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used to evaluate pre- and post-treatment vision. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparison between the groups. All the groups were statistically comparable. All the eyes showed complete regression of CNV, with a minimum follow-up of six months. All groups had visual improvement; significantly in Group 3 (P = 0.003). Combination PDT with anti-VEGF agents appeared to be efficacious in eyes with myopic CNV. However, a larger study with a longer follow-up is required to validate these results.

Keywords: Bevacizumab, choroidal neovascularization, intravitreal injection, myopia, photodynamic therapy, ranibizumab, triamcinolone acetonide, vascular endothelial growth factor

Macular choroidal neovascularization (CNV) is a common vision threatening complication of high myopia.[1] The Verteporfin therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in pathologic myopia (VIP) study[2] has demonstrated no statistical benefit from treatment with photodynamic therapy (PDT) in such eyes, at the end of two years. Intravitreal bevacizumab and ranibizumab have been employed in the treatment of myopic CNV, with encouraging results.[3,4] Combination PDT and intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide (IVTA) has also been reported.[5] This combination is, however, not found to be as effective as PDT monotherapy.

This study analyses the treatment outcomes of CNV secondary to pathological myopia, with different modalities, including PDT monotherapy, combination of PDT with either intravitreal steroids or anti-VEGF agents; and the role of reduced-fluence PDT in combination with intravitreal ranibizumab.

Materials and Methods

Consecutive patients with myopic CNV treated between March 2006 and March 2008 were included. Being retrospective in nature, the ethics committee approval for this study was not sought, as per institutional policy. However, all the procedures followed were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Only eyes with CNV secondary to pathological myopia, defined as an eye with a minimum refractive error of –6 diopters, were included. Evaluation of the patients included recording the best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), fundus photography, digital fluorescein angiography, using the VISUPAC system and the FF 450plus Fundus Camera (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG Göschwitzer Straße 51-52 D-07745 Jena, Germany), and a macular scan with optical coherence tomography (OCT) using Stratus OCT 3.0 (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG Goschwitzer Straße 51-52 D-07745 Jena, Germany). Treatment was administered only if there was evidence of active CNV, that is, presence of leakage on fluorescein angiography and intra-retinal or sub-retinal fluid on OCT. Eleven eyes underwent PDT as per TAP protocol {Treatment of age-related macular degeneration with photodynamic therapy (TAP) Study}[6] [Group 1, Fig. 1]. Three eyes were treated with a combination of PDT and IVTA [Group 2, Fig. 2]. Twelve eyes were treated with a combination of PDT and intravitreal anti-VEGF agents (bevacizumab 1.25 mg/0.05 ml, Fig. 3 or ranibizumab 0.5 mg/0.05 ml, Fig. 4) administered within 48 – 72 hours of PDT (Group 3). Three eyes in Group 3 received verteporfin-PDT with reduced-fluence of 25 J/cm2 followed by intravitreal ranibizumab (0.5 mg/0.05 ml) within 48-72 hours [Fig. 5]. Follow-up examinations were performed at two-month intervals after the first visit, and at monthly intervals, thereafter. Retreatments were based on the activity of CNV as described before. The SPSS 14 software was used to evaluate statistical data. The Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used to evaluate the difference between pre- and post-treatment visual acuity. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparison between the groups.

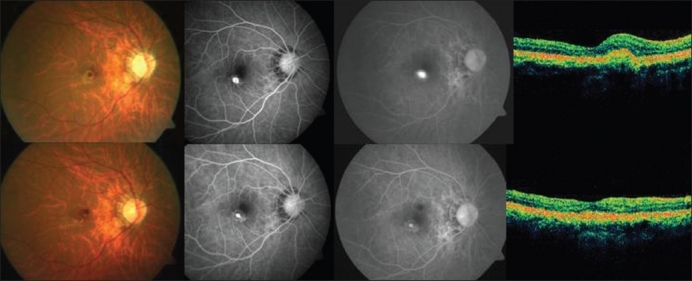

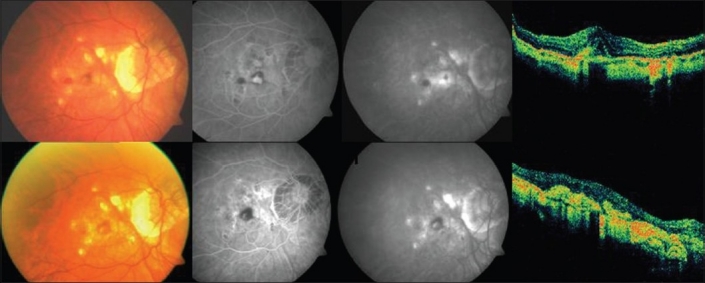

Figure 1.

Top (left to right): Pretreatment color fundus photograph, fluorescein angiography (early and late phases) showing active leakage and optical coherence tomography revealing increased retinal thickness in a case in group 1 (photodynamic monotherapy). Bottom (left to right): Post-treatment color fundus photograph, fluorescein angiography (early and late phases) showing resolution of the leakage with staining of the scar and optical coherence tomography showing a hyper-reflective scar with resolution of fluid in the same case as above

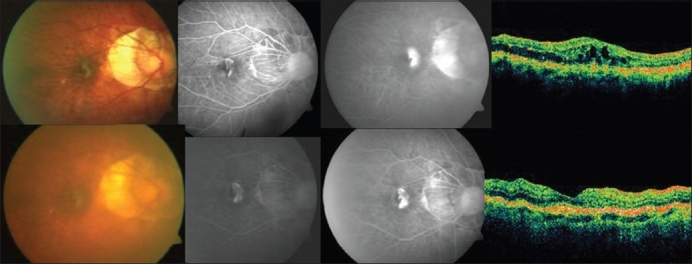

Figure 2.

Top (left to right): Pretreatment color fundus photograph, fluorescein angiography (early and late phases) showing active leakage and optical coherence tomography revealing increased retinal thickness in a case in group 2 (photodynamic therapy + triamcinolone acetonide). Bottom (left to right): Post-treatment color fundus photograph, fluorescein angiography (early and late phases) showing resolution of the leakage with staining of the scar and optical coherence tomography showing a hyper-reflective scar with resolution of fluid in the same case mentioned above

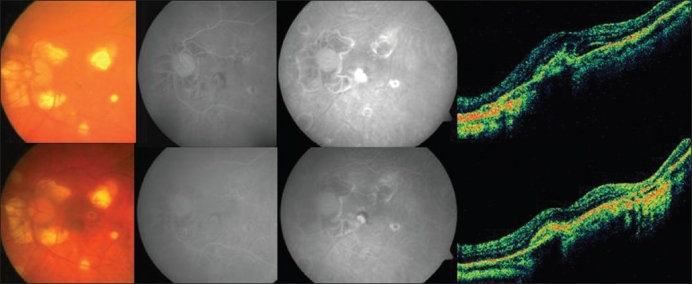

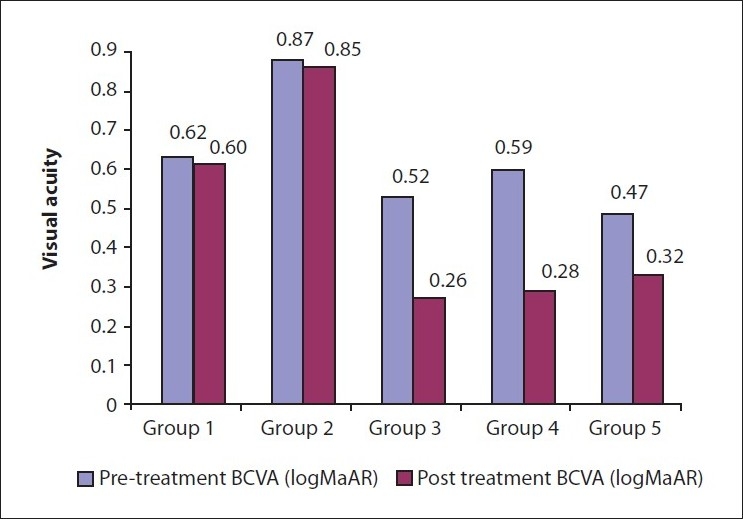

Figure 3.

Top (left to right): Pretreatment color fundus photograph, fluorescein angiography (early and late phases) showing active leakage and optical coherence tomography revealing increased retinal thickness in a case in group 3 (photodynamic therapy and intravitreal bevacizumab). Bottom (left to right): Post-treatment color fundus photograph, fluorescein angiography (early and late phases) showing resolution of the leakage with staining of the scar and optical coherence tomography showing a hyper-reflective scar with resolution of fluid in the same case mentioned above

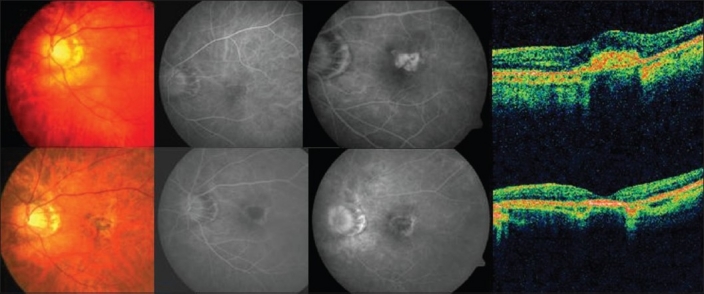

Figure 4.

Top (left to right): Pretreatment color fundus photograph, fluorescein angiography (early and late phases) showing active leakage and optical coherence tomography revealing increased retinal thickness in a case in group 4 (Combination photodynamic therapy and intravitreal ranibizumab). Bottom (left to right): Post-treatment color fundus photograph, fluorescein angiography (early and late phases) shows resolution of the leakage with staining of the scar and optical coherence tomography showing a hyper-reflective scar with resolution of fluid in the same case mentioned above

Figure 5.

Top (left to right): Pretreatment color fundus photograph, fluorescein angiography (early and late phases) showing active leakage and optical coherence tomography revealing increased retinal thickness in a case in group 5 (reduced-fluence photodynamic therapy with ranibizumab). Bottom (left to right): Post-treatment color fundus photograph, fluorescein angiography (early and late phases) showing resolution of the leakage with staining of the scar and optical coherence tomography showing a hyper-reflective scar with resolution of fluid in the same case mentioned above

Results

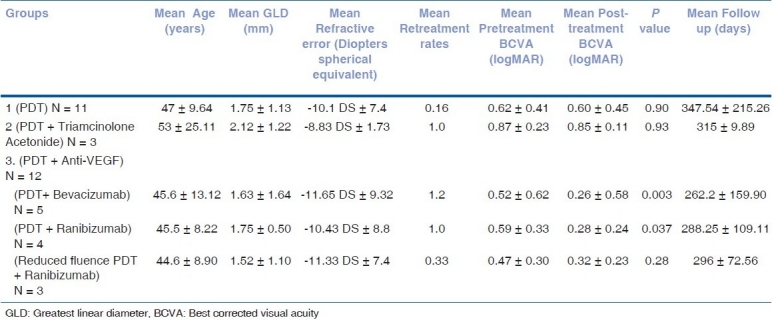

The clinical profiles, visual outcomes, and follow-up of different groups are summarized in Table 1. Angiographically, all CNVs were of the classic type. All groups were statistically comparable in terms of age, presenting BCVA, greatest linear diameter (GLD), and refractive error (Kruskal-Wallis test). Visual improvement, defined as any improvement of 0.2 logMAR, was seen in five (n = 11) eyes in Group 1, two (n = 3) eyes in Group 2, and eleven (n = 12) eyes in Group 3 [Fig. 6]. No correlation between age at onset and final visual acuity was seen in any group. At the last follow-up, all CNVs regressed completely. One patient in group 2 required retreatment with combination therapy. No ocular or systemic adverse reaction was noted in any of the treated eyes till the last follow-up.

Table 1.

Pretreatment clinical features and visual outcomes of different groups

Figure 6.

Bar diagram shows a comparison of pretreatment and post-treatment visual acuities in all the five groups

Discussion

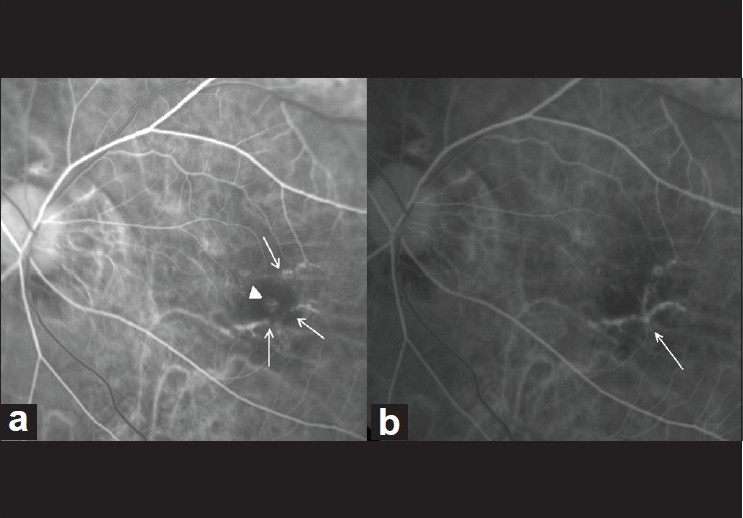

This study reveals better visual outcomes and reduced retreatment rates in eyes treated with combination PDT and anti-VEGF agents. For such eyes treated with PDT alone, the VIP study demonstrated no statistical treatment benefit at the end of two years. Krebs et al,[7] reported that following PDT, the distance visual acuity improved from 43 letters to 53 letters at one year, and was stable thereafter up to three years. A better visual outcome as compared to the VIP study was attributed to fewer numbers of retreatments, as repeated treatments with PDT were associated with hypoxic stress and release of VEGF. Better visual outcome in our study was again attributable to the same reason. In group 1, even though the retreatment rate was 0.16, the degree of visual improvement was less than expected because lacquer cracks were noted to be extending under the fovea in four of these 11 eyes [Fig. 7].

Figure 7.

(a) Pretreatment fluorescein angiography (arteriovenous phase) showing classic choroidal neovascularization (arrow-head) with lacquer cracks (arrows) in a case in group 1 (photodynamic monotherapy). (b) Six months post-treatment fluorescein angiography (arteriovenous phase) showing complete regression of choroidal neovascularization, with extension of lacquer cracks under the fovea (arrow)

Montero et al,[8] stated that as the complications with intravitreal triamcinolone were greater in younger individuals, the combination of PDT and IVTA should be reserved for the elderly who show a poorer response to PDT and have a lower visual acuity, or for patients with recurrent CNVs. Treatment results for Group 2 in our study also reiterate the fact that this modality does not result in a significantly better visual outcome compared to PDT monotherapy.

This study is the first of its kind in analyzing the treatment outcomes of combination PDT with ranibizumab / bevacizumab, for the treatment of myopic CNV. Both combinations are effective in both older and younger age groups with far lesser complications. The average number of treatments in both groups per month can be translated to 0.18 and 0.16, respectively, which is less as compared to those reported in the published studies on bevacizumab monotherapy.[2,9,10] The combined regime is postulated to have a beneficial synergistic effect that can reduce the need for repeated injections.

Selectivity of verteporfin-PDT has been achieved with reduced light dosage that not only causes reduced choroidal occlusion, but also avoids collateral alteration of the physiological choroid and obtains complete CNV closure.[11] Our results with reduced fluence PDT and intravitreal ranibizumab show that the average number of injections required to cause complete CNV regression was 1.33 at 296 days of follow-up. However, the average number of injections required with standard fluence PDT and ranibizumab in our study was two, thus validating the above claim, in principle.

Being retrospective in nature, the study has its own inherent shortcomings. We realize that the numbers in study groups are not large. These constitute the two major drawbacks of this study. In conclusion, a combination therapy of PDT with anti-VEGF agents appears efficacious in the treatment of eyes with CNV secondary to pathological myopia, and may afford better visual outcomes as compared to PDT monotherapy. However, a larger study with a longer follow-up is required to validate these results.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Krishnendu Nandi, MS for his help with statistics.

References

- 1.Yoshida T, Ohno-Matsui K, Yasuzumi K, Kojima A, Shimada N, Futagami S, et al. Myopic choroidal neovascularization: A 10-year follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1297–305. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blinder KJ, Blumenkranz MS, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Donato G, Lewis H, et al. Verteporfin therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in pathologic myopia: 2-year results of a randomized clinical trial-VIP report no. 3. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:667–73. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01998-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamamoto I, Rogers AH, Reichel E, Yates PA, Duker JS. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) as treatment for subfoveal choroidal neovascularistaion secondary to pathological myopia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:157–60. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.096776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silva RM, Ruiz-Moreno JM, Nascimento J, Carneiro A, Rosa P, Barbosaa A, et al. Short-term efficacy and safety of intravitreal ranibizumab for myopic choroidal neovascularization. Retina. 2008;28:1117–23. doi: 10.1097/iae.0b013e31817eda41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan WM, Lai TY, Wong AL, Liu DT, Lam DS. Combined photodynamic therapy and intravitreal triamcinolone injection for the treatment of choroidal neovascularizationsecondary to pathological myopia: A pilot study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:174–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.103606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with verteporfin: One-year results of 2 randomized clinical trials--TAP report: Treatment of age-related macular degeneration with photodynamic therapy (TAP) Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1329–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krebs I, Binder S, Stolba U, Glittenberg C, Brannath W, Goll A. Choroidal neovascularizationin Pathologic Myopia: Three-year results after PDT. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:416–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montero JA, Ruiz-Moreno JM. Combined photodynamic therapy and intravitreal triamcinolone injection for the treatment of choroidal neovascularizationsecondary to pathological myopia: A pilot study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:131–3. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.106526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rheaume MA, Sebag M. Intravitreal Bevacizumab for the treatment of CNV associated with pathological myopia. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008;43:576–80. doi: 10.3129/i08-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakaguchi H, Ikuno Y, Gomi F, Kamei M, Sawa M, Tsujikawa M, et al. Intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin) for subfoveal choroidal neovascularistaion associated with pathological myopia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:161–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.099887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michels S, Hansmann F, Geitzenauer W, Schmidt-Erfurth U. Influence of treatment parameters on selectivity of verteporfin therapy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:371–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]