Abstract

Objective To evaluate the performance of the QFractureScores for predicting the 10 year risk of osteoporotic and hip fractures in an independent UK cohort of patients from general practice records.

Design Prospective cohort study.

Setting 364 UK general practices contributing to The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database.

Participants 2.2 million adults registered with a general practice between 27 June 1994 and 30 June 2008, aged 30-85 (13 million person years), with 25 208 osteoporotic fractures and 12 188 hip fractures.

Main outcome measures First (incident) diagnosis of osteoporotic fracture (vertebra, distal radius, or hip) and incident hip fracture recorded in general practice records.

Results Results from this independent and external validation of QFractureScores indicated good performance data for both osteoporotic and hip fracture end points. Discrimination and calibration statistics were comparable to those reported in the internal validation of QFractureScores. The hip fracture score had better performance data for both women and men. It explained 63% of the variation in women and 60% of the variation in men, with areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.89 and 0.86, respectively. The risk score for osteoporotic fracture explained 49% of the variation in women and 38% of the variation in men, with corresponding areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.82 and 0.74. QFractureScores were well calibrated, with predicted risks closely matching those across all 10ths of risk and for all age groups.

Conclusion QFractureScores are useful tools for predicting the 10 year risk of osteoporotic and hip fractures in patients in the United Kingdom.

Introduction

The World Health Organization defined osteoporosis as a progressive systemic, skeletal disease characterised by low bone mass and micro-architectural deterioration of bone tissue with a consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture.1 In 2000 an estimated 9 million incident cases of osteoporotic fractures occurred worldwide, comprising 1.6 million hip fractures, 1.7 million fractures of the forearm, and 1.4 million vertebral fractures. The annual costs of health and social care for fractures in the United Kingdom are estimated to be £1.8bn (€2bn; $3bn).2

Identifying those at an increased risk of fracture and who might benefit from a therapeutic or preventive intervention is important. QFractureScores are sex specific multivariable risk scores that have recently been developed to predict the 10 year risk of both osteoporotic fracture (vertebra, distal radius, or hip) and hip fracture.3

The risk scores were developed and validated on a large cohort of patients (3.6 million) from the QResearch (www.qresearch.org) database; two thirds of the cohort were randomly allocated to model development and one third to model validation. QResearch is a large database comprising over 12 million anonymised health records from 602 practices throughout the United Kingdom that use the Egton Medical Information Systems (EMIS) computer system (used in 59% of general practices in England). QFractureScores were developed on 2.4 million patients aged between 30 and 85 years contributing 16 million person years of observation, with 32 284 incident diagnoses of osteoporotic fracture, and 14 726 hip fractures, recorded between 1 January 1993 and 30 June 2008. QFractureScores were derived using a Cox proportional hazards model. Fractional polynomials were used to model non-linear risk relations with continuous risk factors, and the presence of interactions between risk factors was tested.4 Multiple imputation was used to replace missing values for key risk factors (smoking status, alcohol consumption, and body mass index) to reduce the biases that can occur in a complete case analysis.5 6 The final prediction model included 17 risk factor terms for women and 12 for men (box). Open source codes to calculate the QFractureScores are available from www.qfracture.org released under the GNU lesser general public licence, version 3. The performance of the QFractureScores was assessed on an additional 1.3 million patients from the QResearch database with 18 471 incident osteoporotic fractures and 7162 incident hip fractures and showed favourable performance when compared with the FRAX (fracture risk assessment) score.7

Risk factors in QFractureScores

Women and men

Age (continuous)

Body mass index (continuous)

Smoking status (non-smoker, former smoker, light smoker (<10 cigarettes/day), moderate smoker (10-19 cigarettes/day), heavy smoker (≥20 cigarettes/day)

Recorded alcohol use (none, trivial <1 unit/day, light 1 or 2 units/day, medium 3-6 units/day, heavy 7-9 units/day, very heavy >9 units/day)

Diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (yes/no)

Diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (yes/no)

Diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (yes/no)

Diagnosis of asthma (yes/no)

At least two prescriptions for tricyclic antidepressants in the six months before baseline (yes/no)

At least two prescriptions for corticosteroids in the six months before baseline (yes/no)

History of falls (yes/no)

Diagnosis of chronic liver disease (yes/no)

Women only

Parental history of osteoporosis (yes/no)

Diagnosis of gastrointestinal malabsorption (yes/no)

Diagnosis of other endocrine symptoms (yes/no)

At least two prescriptions of hormone replacement therapy (yes/no)

Menopausal symptoms (yes/no)

The development of the model and initial internal validation study were both carried out using random samples of data from the same population. External validation is also important to evaluate the model’s performance more widely.8 9 We independently evaluated the performance of QFractureScores on a separate large dataset of general practice records in the United Kingdom.

Methods

Study participants were patients registered between 27 June 1994 and 30 June 2008 with records on the THIN database (www.thin-uk.com). This database comprises the records of general practices that use the INPS Vision system (In Practice Systems, London); currently 20% of UK general practices. Patients were eligible if they were aged between 30 and 85 years, had no previously recorded fracture (hip, distal radius, or vertebra), were permanent residents in the United Kingdom, and had no interrupted periods of registration with a practice.

Primary outcomes

The two primary outcomes were first (incident) diagnosis of an osteoporotic fracture (hip, distal radius, or vertebra) as recorded on the general practice computer records (THIN), and incident diagnosis of hip fracture.

Statistical analysis

We determined an entry date for each patient, which was the latest of the date of their 30th birthday, date of registration with the practice, date on which the practice computer system was installed plus one year, or the beginning of the study period (27 June 1994). Patients were included in the analysis only once they had a minimum of one year’s complete data in their medical record. Observation time was calculated from the entry date to an exit date, which was defined as the earliest date of recorded fracture, date of death, date of deregistration with the practice, date of last upload of computerised data, or the study end date (30 June 2008).

Smoking status (when recorded) was derived from two risk factors: whether the patient was a non-smoker, former smoker, or current smoker, and the number of cigarettes smoked—categorised as light (<10 cigarettes/day), moderate (10-19 cigarettes/day), or heavy (≥20 cigarettes/day). These two risk factors were then combined into five categories: non-smoker, former smoker, light smoker, moderate smoker, and heavy smoker.

Using QFractureScores we calculated the 10 year estimated risk of fracture (osteoporotic and hip) for every patient in the THIN cohort. We used the Kaplan-Meier method to obtain observed 10 year fracture risks. To replace missing values for smoking status, number of cigarettes smoked, alcohol consumption, and body mass index we used multiple imputation using all predictors plus the outcome variable. This involves creating multiple copies of the data and imputing the missing values with sensible values randomly selected from their predicted distribution. We generated five imputed datasets and combined the results from analyses on each of the imputed datasets using Rubin’s rules to produce estimates and confidence intervals that incorporate the uncertainty of imputed values.10

Predictive performance of QFractureScores for the THIN cohort was assessed by examining measures of calibration and discrimination. Calibration refers to how closely the predicted 10 year risk of fracture agrees with the observed 10 year risk of fracture. We assessed this for each 10th of predicted risk, ensuring 10 equally sized groups, and for each five year age band by calculating the ratio of predicted to observed fracture risk separately for men and for women. We assessed the calibration of the risk score predictions by plotting observed proportions versus predicted probabilities. The Brier score for censored survival data was also calculated, which is a measure of accuracy and is the average squared deviation between predicted and observed risk; a lower score represents greater accuracy.11

Discrimination is the ability of the risk score to differentiate between those patients who do and those who do not experience a fracture event during the study. This measure is quantified by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve statistic; a value of 0.5 represents chance and 1 represents perfect discrimination. We also calculated the D statistic12 and R2 statistic,13 which are measures of discrimination and explained variation, respectively, and are tailored towards censored survival data.

All statistical analyses were carried out in R (version 2.11.1)14 and the imputation by chained equations (ICE) procedure in Stata (version 11).15

Results

Between 27 June 1994 and 30 June 2008, 2 244 636 eligible patients from 364 general practices in the United Kingdom were registered in the THIN database. For the osteoporotic fracture end point, 2 209 451 patients (50.6% women) were eligible for analysis (27 551 had a recorded fracture before 27 June 1994 and were excluded) contributing 12 784 326 person years of observation, of which there were 25 208 incident cases of osteoporotic fracture. For the hip fracture end point, 2 244 636 patients were eligible for analysis (5202 had a recorded hip fracture before 27 June 1994 and were excluded) contributing 13 053 891 person years of observation, of which there were 12 188 incident cases of hip fracture. The median follow-up for the osteoporotic fracture end point was 5.98 (interquartile range 2.61-8.50) years and for the hip fracture end point was 6.03 (2.62-8.50) years. In total, 319 991 patients (14.5%) were followed up for 10 years or more for the osteoporotic end point and 329 571 patients (14.7%) for the hip fracture end point.

The 10 year observed risk of osteoporotic fracture in women (19 055 incident osteoporotic fractures) aged between 30 and 85 was 3.04% (95% confidence interval 2.99% to 3.09%) and in men (6153 incident osteoporotic fractures) was 1.04% (1.01% to 1.07%). The 10 year observed risk of hip fracture in women (9165 incident hip fractures) aged between 30 and 85 was 1.48% (1.44% to 1.51%) and in men (3023 incident hip fractures) was 0.52% (0.50% to 0.54%). Table 1 details the characteristics of the patients in the THIN cohort.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients aged 30 to 85 years in THIN database. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Derivation cohort (QResearch) | External validation cohort (THIN) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n=1 183 663) | Men (n=1 174 232) | Women (n=1 136 417) | Men (n=1 108 219) | |||

| Median (interquartile range) age (years) | 48 (37-62) | 46 (37-59) | 48 (37-62) | 47 (37-59) | ||

| Alcohol consumption: | ||||||

| None | 275 984 (23.3) | 140 925 (12.0) | 243 624 (21.4) | 132 872 (12.0) | ||

| Trivial <1 unit/day | 341 295 (28.8) | 226 118 (19.3) | 288 754 (25.4) | 168 374 (15.2) | ||

| Light 1 or 2 units/day | 162 433 (13.7) | 234 460 (20.0) | 71 616 (6.3) | 72 962 (6.6) | ||

| Moderate 3-6 units/day | 19 455 (1.6) | 96 202 (8.2) | 17 911 (1.6) | 48 270 (4.4) | ||

| Heavy 7-9 units/day | 1208 (0.1) | 11 006 (0.9) | 1558 (0.1) | 7986 (0.7) | ||

| Very heavy >9 units/day | 1231 (0.1) | 8877 (0.8) | 1178 (0.1) | 5046 (0.5) | ||

| Not recorded | 382 063 (32.4) | 456 616 (38.9) | 511 776 (45.0) | 672 709 (60.7) | ||

| Body mass index: | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 25.88 (4.9) | 26.43 (4.1) | 26.15 (5.0) | 26.63 (4.1) | ||

| Not recorded | 299 140 (25.3) | 392 613 (33.4) | 200 192 (17.6) | 270 900 (24.4) | ||

| Smoking status: | ||||||

| Non-smoker | 630 470 (53.3) | 462 344 (38.9) | 530 062 (46.6) | 401 760 (36.3) | ||

| Former smoker | 139 496 (11.8) | 173 503 (14.6) | 125 816 (11.1) | 158 600 (14.3) | ||

| Current smoker: | ||||||

| Light (<10 cigarettes/day) | 51 945 (4.4) | 69 504 (5.9) | 70 741 (6.2) | 68 077 (6.1) | ||

| Moderate (10-19 cigarettes/day) | 131 563 (11.1) | 146 959 (12.4) | 109 052 (9.6) | 104 844 (9.5) | ||

| Heavy (≥20 cigarettes/day) | 54 489 (4.6) | 77 147 (6.5) | 77 828 (6.9) | 117 567 (10.6) | ||

| Amount not recorded | 175 700 (14.8) | 244 775 (20.9) | 153 448 (13.5) | 137 617 (12.4) | ||

| Not recorded | 175 700 (14.8) | 244 775 (20.9) | 69 470 (6.1) | 119 754 (10.8) | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 9459 (0.8) | 3903 (0.3) | 12 340 (1.1) | 5260 (0.5) | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 41 842 (3.5) | 62 265 (5.2) | 54 520 (4.8) | 76 585 (6.9) | ||

| Type 2 diabetes | 22 645 (1.9) | 27 637 (2.3) | 28 039 (2.5) | 35 157 (3.2) | ||

| Asthma | 66 892 (5.7) | 55 888 (4.7) | 97 177 (8.6) | 78 079 (7.1) | ||

| Current tricyclic antidepressants | 46 054 (3.9) | 14 646 (1.2) | 59 803 (5.3) | 23 048 (2.1) | ||

| Current corticosteroids | 20 005 (1.7) | 11 569 (1.0) | 36 752 (3.2) | 23 686 (2.1) | ||

| History of falls | 8801 (0.7) | 4676 (0.4) | 29 106 (2.6) | 14 911 (1.4) | ||

| Chronic liver disease | 1563 (0.1) | 2133 (0.2) | 1892 (0.2) | 2586 (0.2) | ||

| Gastrointestinal malabsorption | 5970 (0.5) | 4851 (0.4) | 6388 (0.6) | 5047 (0.5) | ||

| Other endocrine conditions | 8615 (0.7) | 1886 (0.2) | 9665 (0.9) | 2124 (0.2) | ||

| Menopausal conditions | 25 683 (2.2) | — | 58 507 (5.2) | — | ||

| 10 year osteoporotic fracture risk (95% CI) | Not reported | Not reported | 3.04 (2.99 to 3.09) | 1.04 (1.01 to 1.07) | ||

| 10 year hip fracture risk (95% CI) | Not reported | Not reported | 1.48 (1.44 to 1.51) | 0.52 (0.50 to 0.54) | ||

| Country: | ||||||

| England: | Not reported | Not reported | 980 465 (86.3) | 956 465 (86.3) | ||

| Northern Ireland | Not reported | Not reported | 31 478 (2.8) | 29 428 (2.7) | ||

| Scotland | Not reported | Not reported | 61 563 (5.4) | 59 754 (5.4) | ||

| Wales | Not reported | Not reported | 62 911 (5.5) | 62 572 (5.7) | ||

Complete data on smoking status, smoking category, alcohol consumption, and body mass index were available for 44.5% of women (n=506 081) and 31.8% of men (n=352 380). Most patients (n=1 693 039; 75.4%) had no or only one missing risk factor (table 2). Missing data were noticeably high for alcohol consumption (45.0% for women and 60.7% for men). For other risk factors 17.6% of women and 24.4% of men had missing data on body mass index, 13.5% and 12.4% on smoking status, and 6.1% and 10.8% for number of cigarettes smoked.

Table 2.

Completeness of data

| No of risk factors not recorded (per patient) | No (%) of women (n=1 136 417) | No (%) of men (n=1 108 219) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (no missing data) | 506 081 (44.5) | 352 380 (31.8) |

| 1 | 398 859 (35.1) | 435 719 (39.3) |

| 2 | 151 328 (13.3) | 186 061 (16.8) |

| 3 | 17 755 (1.6) | 23 343 (2.1) |

| 4 | 62 394 (5.5) | 110 716 (10.0) |

Table 3 shows the incidence rates (per 1000 person years) for fracture by age and sex in the THIN cohort. Women experienced 19 055 fractures during 6 493 740 person years of follow-up: incidence rate 2.93 (95% confidence interval 2.89 to 2.98). Men experienced 6153 osteoporotic fractures during 6 290 586 person years of follow-up: incidence rate 0.98 (0.95 to 1.00). The rates of osteoporotic fracture were highest in those aged 80 to 85 years at baseline: incidence rate in women 17.7 (17.14 to 18.28) and in men 7.01 (6.54 to 7.51). Hip fractures accounted for 48.1% of fractures in women and 49.1% in men. Overall, 9165 hip fractures were recorded for women during the 6 673 972 person years of follow-up, giving an overall incidence rate of 1.37 (1.35 to 1.40), whereas for men, 3023 incident hip fractures occurred during 6 379 919 person years of follow-up, giving an incident rate of 0.47 (0.46 to 0.49). Among those aged 80 to 85 years the incidence of hip fracture in women was 12.47 (12.02 to 12.94) and in men was 5.42 (5.01 to 5.86).

Table 3.

Incidence rates of osteoporotic fracture (distal radius, hip, or vertebra) and hip fracture per 1000 person years in THIN cohort by age at baseline in men and women

| Age (years) | Osteoporotic fractures | Hip fractures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person years of observation | No of fractures | Rate/1000 person years (95% CI) | Person years of observation | No of fractures | Rate/1000 person years (95% CI) | |

| Women: | ||||||

| 30-34 | 917 642 | 386 | 0.42 (0.38 to 0.46) | 925 879 | 31 | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.05) |

| 35-39 | 886 876 | 393 | 0.44 (0.40 to 0.49) | 895 173 | 38 | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.06) |

| 40-44 | 774 263 | 468 | 0.60 (0.55 to 0.66) | 782 832 | 60 | 0.08 (0.06 to 0.10) |

| 45-49 | 727 432 | 701 | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.04) | 736 908 | 132 | 0.18 (0.15 to 0.21) |

| 50-54 | 714 507 | 1119 | 1.57 (1.48 to 1.66) | 726 914 | 226 | 0.31 (0.27 to 0.35) |

| 55-59 | 600 457 | 1331 | 2.22 (2.10 to 2.34) | 615 661 | 345 | 0.56 (0.50 to 0.62) |

| 60-64 | 513 369 | 1815 | 3.54 (3.37 to 3.70) | 533 233 | 539 | 1.01 (0.93 to 1.10) |

| 65-69 | 455 260 | 2344 | 5.15 (4.94 to 5.36) | 479 425 | 946 | 1.97 (1.85 to 2.10) |

| 70-74 | 388 396 | 3135 | 8.07 (7.79 to 8.36) | 416 219 | 1652 | 3.97 (3.78 to 4.17) |

| 75-79 | 306 809 | 3668 | 11.96 (11.57 to 12.35) | 332 570 | 2338 | 7.03 (6.75 to 7.32) |

| 80-85 | 208 730 | 3695 | 17.70 (17.14 to 18.28) | 229 159 | 2858 | 12.47 (12.02 to 12.94) |

| Total | 6 493 740 | 19 055 | 2.93 (2.89 to 2.98) | 6 673 972 | 9165 | 1.37 (1.35 to 1.40) |

| Men: | ||||||

| 30-34 | 916 590 | 412 | 0.45 (0.41 to 0.50) | 929 528 | 45 | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.06) |

| 35-39 | 911 311 | 409 | 0.45 (0.41 to 0.49) | 924 254 | 77 | 0.08 (0.07 to 0.10) |

| 40-44 | 809 997 | 355 | 0.44 (0.39 to 0.49) | 821 559 | 76 | 0.09 (0.07 to 0.12) |

| 45-49 | 749 353 | 412 | 0.55 (0.50 to 0.61) | 760 068 | 116 | 0.15 (0.13 to 0.18) |

| 50-54 | 729 014 | 489 | 0.67 (0.61 to 0.73) | 739 153 | 163 | 0.22 (0.19 to 0.26) |

| 55-59 | 603 892 | 445 | 0.74 (0.67 to 0.81) | 611 878 | 189 | 0.31 (0.27 to 0.36) |

| 60-64 | 500 299 | 489 | 0.98 (0.89 to 1.07) | 507 598 | 218 | 0.43 (0.37 to 0.49) |

| 65-69 | 417 588 | 595 | 1.42 (1.31 to 1.54) | 423 791 | 333 | 0.79 (0.70 to 0.87) |

| 70-74 | 321 199 | 865 | 2.69 (2.52 to 2.88) | 325 637 | 545 | 1.67 (1.54 to 1.82) |

| 75-79 | 215 248 | 868 | 4.03 (3.77 to 4.31) | 218 448 | 621 | 2.84 (2.62 to 3.08) |

| 80-85 | 116 096 | 814 | 7.01 (6.54 to 7.51) | 118 005 | 640 | 5.42 (5.01 to 5.86) |

| Total | 6 290 586 | 6153 | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.00) | 6 379 919 | 3023 | 0.47 (0.46 to 0.49) |

Table 4 presents the performance data on discrimination and calibration for the QFractureScores in the THIN cohort alongside those previously reported in the internal validation using the QResearch cohort.3 The R2 statistic (percentage of explained variation) was about 4% higher for the osteoporotic fracture score in women and 8% higher in men compared with the internal validation performance data. For the hip fracture score, the R2 statistic was marginally lower for both women (1%) and men (3%) in the THIN cohort compared with the internal validation. The D statistic was noticeably higher for hip fracture in both women and men (2.66 and 2.53) than for osteoporotic fracture (2.02 and 1.60). The D statistics of QFractureScores for osteoporotic fracture were higher in the external validation than in the internal validation. Values for the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve were higher for osteoporotic fracture in the THIN cohort in both women and men (0.816 and 0.739) than in the internal validation (0.788 and 0.688). Values for the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for hip fracture alone were higher than for osteoporotic fracture, whereas values were comparable to those obtained in the internal validation. The Brier score (adjusted for censoring), a measure of prediction accuracy, was better for hip fracture than for osteoporotic fracture.

Table 4.

Discrimination and calibration performance data for QFractureScores in THIN cohort

| Variables | Internal validation cohort (QResearch) | External validation cohort (THIN) | THIN (complete case) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |||

| Osteoporotic fracture: | ||||||||

| R2* (95% CI) | 44.87 (43.07 to 46.67) | 30.02 (22.21 to 37.84) | 49.24 (48.64 to 49.85) | 37.99 (36.64 to 39.35) | 48.93 (46.93 to 48.72) | 37.04 (34.92 to 39.16) | ||

| D statistic† (95% CI) | 1.85 (1.78 to 1.91) | 1.34 (1.09 to 1.59) | 2.02 (1.99 to 2.04) | 1.60 (1.56 to 1.65) | 1.96 (1.92 to 2.00) | 1.56 (1.50 to 1.64) | ||

| Area under ROC curve (95% CI) | 0.788 (0.786 to 0.790) | 0.688 (0.684 to 0.692) | 0.816 | 0.739 | 0.810 | 0.742 | ||

| Brier score‡ (95% CI) | Not calculated | Not calculated | 0.027 (0.025 to 0.029) | 0.010 (0.008 to 0.012) | 0.029 (0.026 to 0.031) | 0.012 (0.009 to 0.015) | ||

| Hip fracture: | ||||||||

| R2* (95% CI) | 63.94 (62.12 to 65.76) | 63.19 (60.81 to 65.57) | 62.82 (62.22 to 63.43) | 60.42 (59.22 to 61.63) | 62.19 (61.24 to 63.11) | 57.41 (55.27 to 59.43) | ||

| D statistic† (95% CI) | 2.73 (2.62 to 2.83) | 2.68 (2.55 to 2.82) | 2.66 (2.63 to 2.70) | 2.53 (2.46 to 2.59) | 2.62 (2.57 to 2.68) | 2.38 (2.28 to 2.48) | ||

| Area under ROC curve (95% CI) | 0.890 (0.889 to 0.892) | 0.856 (0.851 to 0.860) | 0.890 | 0.855 | 0.884 | 0.843 | ||

| Brier score‡ (95% CI) | Not calculated | Not calculated | 0.013 (0.012 to 0.015) | 0.005 (0.003 to 0.007) | 0.014 (0.011 to 0.016) | 0.006 (0.003 to 0.010) | ||

ROC=receiver operating characteristic.

*Percentage of explained variation.

†Measure of discrimination.

‡Measure of prediction accuracy—that is, the average squared deviation between predicted and observed risk; a lower score represents greater accuracy.

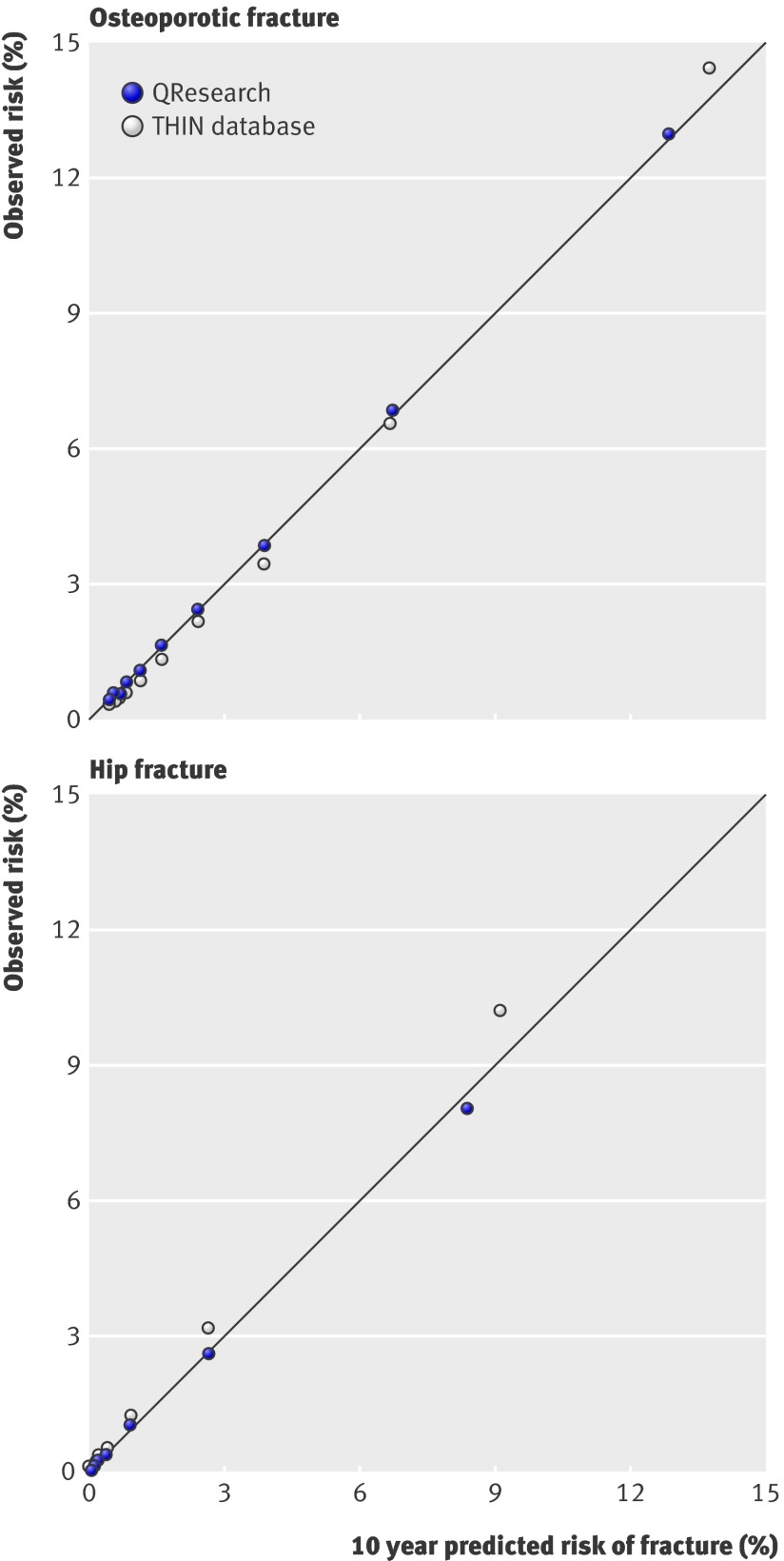

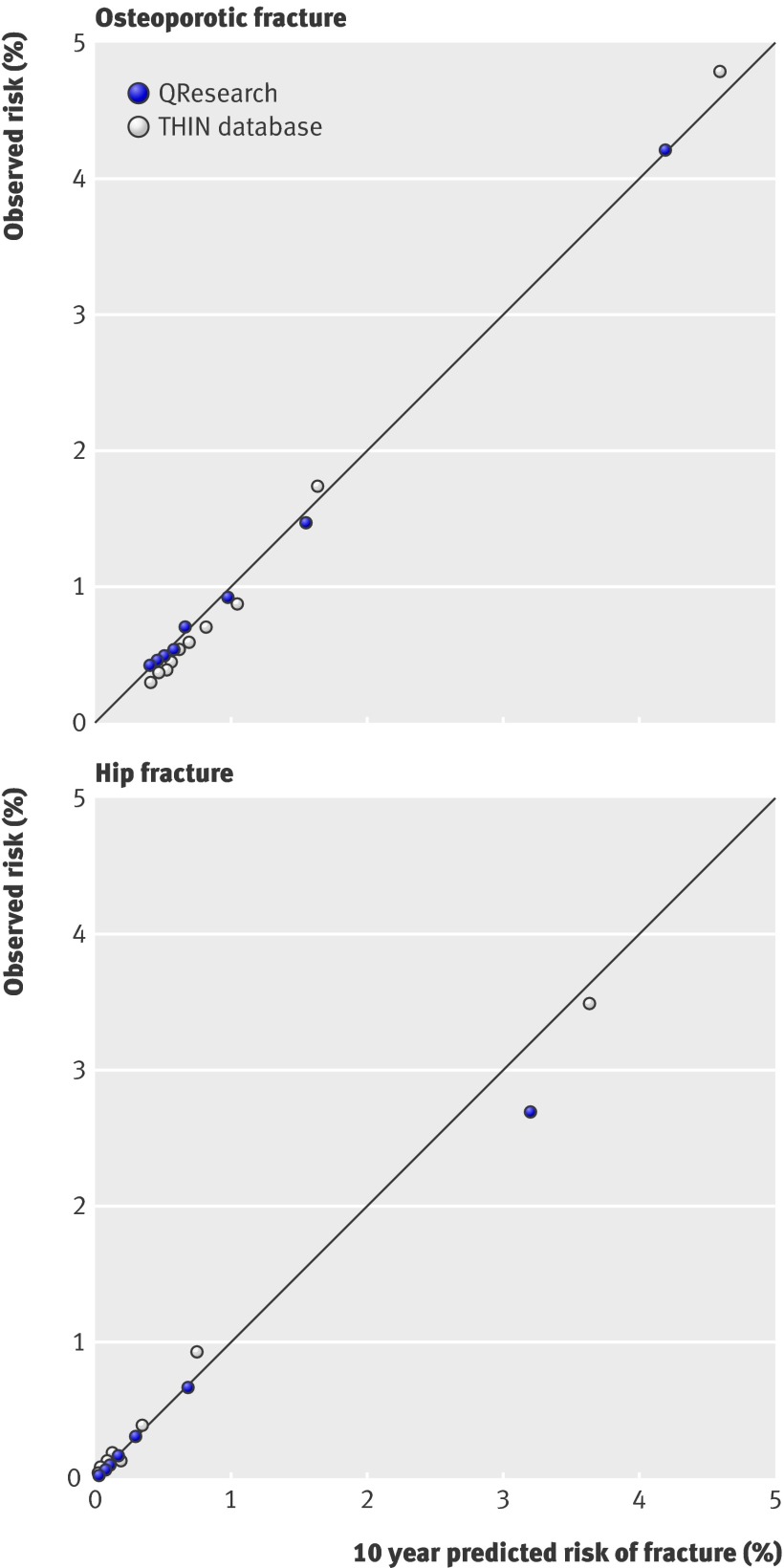

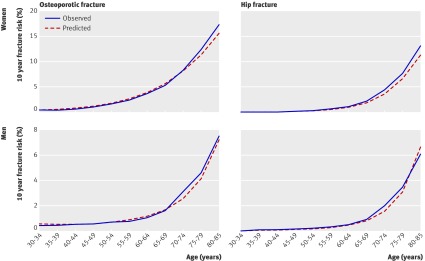

Figures 1 and 2 present the calibrations of QFractureScores for men and women by 10th of risk for both the THIN cohort (external validation) and the QResearch cohort (internal validation). Model calibration was good, with close agreement between predicted and observed risk of osteoporotic and hip fractures across all 10ths of risk, with no discernible over-prediction or under-prediction. Similarly, figure 3 displays the calibration of QFractureScores for men and women by age group. Agreement between predicted and observed fracture risks was close across all age groups.

Fig 1 Observed versus predicted fracture risks for women. THIN=The Health Improvement Network

Fig 2 Observed versus predicted fracture risks for men. THIN=The Health Improvement Network

Fig 3 Observed and predicted fracture risk by age group and sex

Discussion

QFractureScores are four new risk scores for predicting the 10 year risk of osteoporotic and hip fracture separately in men and women, developed and internally validated on the large UK primary care electronic QResearch database.3 The database comprised 3.7 million patients registered between 1 January 1993 and 30 June 2008, contributing 50 755 osteoporotic fractures, 19 531 hip fractures, and 25 million person years of observation using the EMIS computer system.

QFractureScores were designed to be based on risk factors that are readily available and recorded in patients’ health records or which patients themselves are likely to know. Other risk scores for predicting osteoporotic fracture have included clinical ones such as loss of bone mineral density, as measured by dual energy x ray absorptiometry.7 16 The rationale for excluding laboratory tests or clinical measurements in QFractureScores was to make the score readily available and cost effective so that it could be easily implemented in routine clinical practice and national screening initiatives. All the variables in the QFractureScores will be known to the patient or collected as part of routine clinical practice and recorded within the patients’ healthcare record. Thus QFractureScores can be applied in primary care to identify patients who are at high risk and would benefit from further investigation without the need for expensive tests to identify those at an increased risk.

WHO has recently developed a risk prediction model, the FRAX (fracture risk assessment) instrument, to predict individual risks of fracture.7 FRAX has been incorporated into clinical guidelines in the United Kingdom and United States17 18 19 and uses information on age, sex, height, body mass index, previous fracture, family history of fracture, glucocorticoid use, current smoking status, alcohol consumption, rheumatoid arthritis, other secondary causes of osteoporosis, and, if available, bone mineral density of the femoral neck. The details and source code for the calculation of an individual’s risk using FRAX has to date not been published or released for independent evaluation. We sought to compare QFractureScores against FRAX for the hip fracture end point but our requests for an independent head to head comparison were not taken up by the developers of FRAX.

Although the development and intended use of QFractureScores were for the United Kingdom, the risk factors in both the osteoporotic and the hip fracture models include no UK specific terms (such as the Townsend deprivation score as used in other QResearch risk scores or ethnicity). There is thus no reason why the QFractureScores could not be used outside the United Kingdom; however, the performance of the models would need to be established before use in a different population.

Our independent evaluation of QFractureScores was carried out on the large separate database (THIN) based on general practices recording clinical data using the INPS Vision system, which is used in 20% of UK general practices. The dataset comprised 2.2 million patients registered between 27 June 1994 and 30 June 2008, contributing 13 million person years of observation. The performance data presented in this article on the THIN cohort provide strong evidence to support the external validity of QFractureScores in predicting 10 year risk of osteoporotic or hip fracture, with comparable performance to that observed in the internal validation data. QFractureScores for osteoporotic and hip fracture end points in both women and men were well calibrated in this large cohort, with good agreement between predicted and observed risks. Discriminant ability in both the internal validation and the external validation are impressive, with values for the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve exceeding 0.8 for women and 0.73 for osteoporotic fracture in men and 0.86 for hip fracture in men.

To date, the development, internal validation, and our external validation of QFractureScores have used 5.9 million patients. These patients have contributed 38 million person years of observation and 75 963 new cases of osteoporotic fractures and 31 719 of hip fractures during the observation periods. Such data have been used to develop and evaluate four risk scores to predict the 10 year risk of osteoporotic and hip fracture in adults aged 30 to 85.

Conclusions

In this study, we have provided an independent and external validation of the QFractureScores risk score on a large cohort of patients in the United Kingdom. We have assessed the performance of QFractureScores against the performance data from the internal validation of QFractureScores with comparable results and shown good evidence to confirm predictive power of the risk scores without the need for recalibration.

What is already known on this topic

International guidelines propose a targeted approach based on a 10 year absolute fracture risk for identifying high risk patients who may benefit from interventions

QFractureScores were developed and internally validated using a large cohort of UK patients and published in 2009

Risk prediction models need to be independently and externally validated to objectively evaluate performance

What this study adds

Results from this independent and external validation of QFractureScores indicated good performance data for both osteoporotic and hip fracture end points

The performance data for both risk prediction models, especially for hip fracture score, suggest that the QFractureScores could be useful in identifying patients in the UK who are at increased risk of osteoporotic fracture who could benefit from interventions

Contributors: GSC carried out the analysis and prepared the first draft, which was revised according to comments and suggestions from SM and DGA. GSC is guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not for profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Trent multicentre research ethics committee.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;342:d3651

References

- 1.Consensus development conference: diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of osteoporosis. Am J Med 1999;94:646-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burge RT, Worley D, Johansen A, Bose U. The cost of osteoporotic fractures in the United Kingdom. J Med Econ 2001;4:51-62. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Predicting risk of osteoporotic fracture in men and women in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QFractureScores. BMJ 2009;339:b4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royston P, Ambler G, Sauerbrei W. The use of fractional polynomials to model continuous risk variables in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 1999;28:964-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vergouwe Y, Royston P, Moons KG, Altman DG. Development and validation of a prediction model with missing predictor data: a practical approach. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:205-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: a primer. Stat Med 1999;18:2529-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int 2008;19:385-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altman DG, Royston P. What do we mean by validating a prognostic model? Stat Med 2000;19:453-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altman DG, Vergouwe Y, Royston P, Moons KGM. Prognosis and prognostic research: validating a prognostic model. BMJ 2009;338:b605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley, 1987.

- 11.Graf E, Schmoor C, Sauerbrei W, Schumacher M. Assessment and comparison of prognostic classification schemes for survival data. Stat Med 1999;18:2529-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Royston P, Sauerbrei W. A new measure of prognostic separation in survival data. Stat Med 2004;23:723-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royston P. Explained variation for survival models. Stata J 2006;6:83-96. [Google Scholar]

- 14.R Project. The R Project for statistical computing [program]. 2011. www.R-project.org.

- 15.StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 11 [program]. StataCorp, 2009.

- 16.Nguyen ND, Frost SA, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Development of prognostic nomograms for individualizing 5-year and 10-year fracture risks. Osteoporos Int 2008;19:1431-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawson-Hughes B. A revised clinician’s guide to the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:2463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Compston J, Cooper A, Cooper C, Francis R, Kanis JA, Marsh D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men from the age of 50 years in the UK. Maturitas 2009;62:105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. 2011. www.nof.org/professionals/clinical-guidelines.