Abstract

Background

Environmental enrichment (EE) enhances motor and cognitive performance after traumatic brain injury (TBI). However, whether the EE-mediated benefits are time-dependent and task-specific is unclear. A preliminary study, in which only half of the possible temporal manipulations were evaluated, revealed that the beneficial effects of enrichment were only observed when provided concurrently with specific training (i.e., motor or cognitive), suggesting task-specific dependence.

Objective

To further assess the effects of time of initiation and duration of EE on neurobehavioral recovery after TBI by evaluating and directly comparing all the temporal permutations.

Methods

Anesthetized adult male rats received either a cortical impact or sham injury and were then randomly assigned to eight groups receiving continuous, or early and delayed EE with either 1 or 2 weeks of exposure. Functional outcome was assessed with established motor (beam-balance/walk) and cognitive (Morris water maze) tests on post-injury days 1-5 and 14-18, respectively.

Results

Motor ability was enhanced in the TBI groups that received early EE (i.e., during testing) vs. standard housing. In contrast, acquisition of spatial learning was facilitated in the groups receiving delayed EE (i.e., during training).

Conclusions

These data support the conclusion from the previous study that EE-mediated functional improvement after TBI is contingent on task-specific neurobehavioral experience, and extends those preliminary findings by demonstrating that the duration of enriched exposure is also important for functional recovery.

Keywords: beam-walking, controlled cortical impact, functional recovery, learning and memory, Morris water maze, neurobehavior, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Environmental enrichment (EE) consists of increased living space, various complex stimuli that stimulate the senses, and social interaction that promotes exploration of the surroundings 1. EE is typically introduced immediately after traumatic brain injury (TBI) and is continued until all behavioral manipulations have been completed. This paradigm has consistently shown improvement on motor and cognitive performance after brain trauma 1-6 and is thus considered a reasonable approach to preclinical rehabilitation 1,4,5. However, the continuous-exposure nature of the current EE model is inconsistent with the clinical scenario where patients typically do not begin rehabilitation immediately after injury and also may not receive similar lengths of rehabilitation.

Hence, it is important to discern as much information about the EE paradigm as possible so that it may be adapted to function as a rehabilitation-relevant model. A missing link in the current model that is vital to the rehabilitation approach is that it is not well known whether the EE-mediated benefits after TBI are contingent on immediate and continuous enrichment or if delayed and intermittent exposure prior to or during neurobehavioral training is sufficient. A preliminary investigation from our laboratory set out to address this important question and found that the benefits of EE were only observed when provided concurrently with specific training (i.e., motor or cognitive), suggesting task-specific dependence 4. However, a limitation of that experiment was that only half of the possible temporal permutations were evaluated. Thus, the goal of the current study is to extend and further assess the time of initiation and duration of EE on neurobehavioral recovery after TBI by evaluating and directly comparing all temporal permutations such that a clearer understanding emerges. The hypothesis is that the additional evaluations will support the conclusion of the previous study by demonstrating optimal effect on behavioral recovery when EE is provided concurrently with specific behavioral testing or training (i.e., beam-walking or spatial learning in a water maze). It is further predicted that groups receiving longer durations of EE will perform better than those receiving limited exposure.

Methods

Subjects and groups

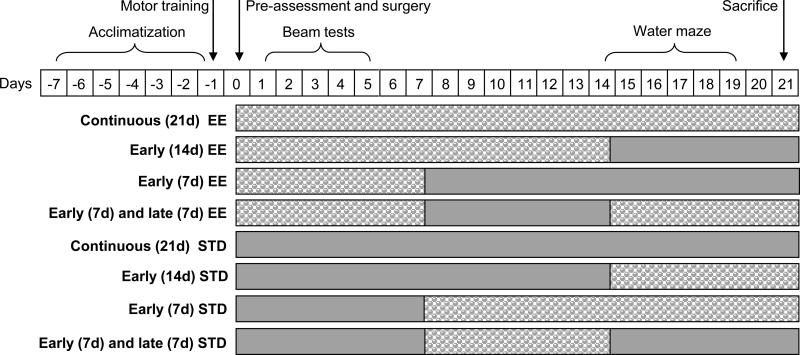

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) weighing 300-325 g on the day of surgery were initially housed in standard steel-wire mesh cages and maintained in a temperature (21 ± 1°C) and light controlled (on 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m.) environment with food and water available ad libitum. After one week of acclimatization the rats underwent a single day of beam-walk training, which consisted of placing the rats on the beam for 3-5 trials until they could traverse the beam in order to escape aversive stimuli (i.e., light and white noise). Once the rats were skilled at completing the beam task they were prepared for surgery. Briefly, isoflurane (4% in 2:1 N2O/O2) anesthetized rats were intubated, mechanically ventilated, and then subjected to either a right hemisphere controlled cortical impact (2.8 mm tissue deformation at 4 m/sec) or sham injury 7-8. Core temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C during surgery. Following the cessation of anesthesia, the rats underwent acute neurological assessments, which consisted of recording the latency of hind limb reflexive ability after a gentle squeeze of the rats paw and return of the righting reflex. Following surgery, the rats were randomly assigned to either EE or standard (STD) housing and the following eight temporal manipulations (n=10 per group): TBI + continuous (21d) EE, TBI + early (14d) EE, TBI + early (7d) EE, TBI + early (7d) + delayed (7d) EE, TBI + continuous (21d) STD, TBI + early (14d) STD, TBI + early (7d) STD, and TBI + early (7d) + late (7d) STD. Sham controls were also evaluated for each condition (n=3 per group).

Housing: environmental enrichment vs. standard

The groups designated for early or continuous EE were immediately placed in a 36×20×18 inch steel-wire cage consisting of three levels (with ladders to ambulate from one level to another) with various toys (e.g., balls and blocks of various sizes), tubes for tunneling, nesting materials (e.g., cloth and paper towels), and ad libitum food and water 1,5. To maintain novelty, the objects were rearranged every day and changed each time the cage was cleaned, which was approximately every 3 days. Ten to twelve rats, which included both TBI and sham controls, were housed in the EE at any given time. Rats in the STD conditions were placed in regular sized steel-wire mesh cages (2 rats per cage) with only food and water. See Fig. 1 for a schematic of the housing manipulations. As indicated above, all experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh and were conducted in accordance with the recommendations provided in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy Press, 1996). Every attempt was made to limit the number of animals used and to minimize suffering.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the experimental paradigm for TBI rats exposed to the various EE manipulations. Only TBI groups are depicted for simplicity, but sham controls underwent the same time management. Filled bars = EE.

Motor: beam-balance and beam-walk

Motor function was assessed by established beam-balance (BB) and beam-walk (BW) tasks. The BB task consists of placing the rat on an elevated (90 cm) narrow wooden beam (1.5 cm wide) and recording the time it remains on for a maximum of 60 sec. The BW task consists of recording the elapsed time to traverse the beam. Rats were tested for BB and BW performance immediately before surgery (to establish a baseline measure), as well as on post-operative days 1–5, and consisted of three trials (60 sec allotted time with an intertrial interval of 30 sec) per day on each task. The average daily scores for each subject were used in the statistical analyses.

Cognitive: acquisition of spatial learning

Spatial learning was assessed in a Morris water maze (MWM) task 9 shown to be sensitive to cognitive function/dysfunction after TBI 1,5,10,11. Briefly, the maze consisted of a plastic pool (180 cm diameter; 60 cm high) filled with tap water (26 ± 1°C) to a depth of 28 cm and was situated in a room with salient visual cues. The platform was a clear Plexiglas stand that was positioned in the southwest quadrant and held constant for each rat. Spatial learning acquisition began on post-operative day 14 and consisted of providing a block of four daily trials (4-min inter-trial interval) for five consecutive days (14–18) to locate the platform when it was submerged 2 cm below the water surface (i.e., invisible to the rat). On post-operative day 19 the platform was raised 2 cm above the water surface (i.e., visible to the rat) as a control procedure to determine the contributions of non-spatial factors (e.g., sensory-motor performance, motivation, and visual acuity) on MWM performance. Swim speed was also assessed on this day. Each trial lasted until the rat climbed onto the platform or until 120 sec had elapsed, whichever occurred first. Rats that failed to locate the goal within the allotted time were manually guided to it. All rats remained on the platform for 30 sec and then placed in a heated incubator between trials. The times of the 4 daily trials for each rat were averaged and used in the statistical analyses. The data were obtained using a spontaneous motor activity recording & tracking (SMART) system (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA).

Statistical analyses

The data were collected by observers blinded to treatment conditions and statistical analyses were performed using Statview 5.0.1 software (Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, CA). The motor and cognitive data were analyzed by repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The acute neurological assessments and swim speed data were analyzed by one-factor ANOVAs. When the overall ANOVAs revealed a significant effect, the Bonferroni/Dunn post-hoc test was used to determine specific group differences. The data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) and are considered significant when corresponding p values are ≤ 0.05 or as determined by the Bonferroni/Dunn statistic after correcting for multiple comparisons; given the numerous groups, the corrected p value for significance was ≤ 0.0014.

Results

Acute neurological assessments

No significant differences were observed among the TBI groups in hind limb withdrawal response latencies after a brief paw pinch [range 168.3 ± 2.7 sec to 181.6 ± 6.1 sec, p > 0.0014] or for return of the righting reflex [range 364.8 ± 15.6 sec to 375.9 ± 18.5 sec, p > 0.0014] after the cessation of anesthesia. The lack of significant differences with these acute neurological indices suggests that all TBI groups experienced an equivalent level of injury and anesthesia. Despite similar injury severity, two rats from the “TBI + early (7d) + delayed (7d) EE” group were unable to locate the visible platform, which may be indicative of visual deficits, and were therefore excluded from the study. Thus, the statistical analyses are based on one-hundred-and-two rats. Furthermore, because there were no significant differences in any outcome measure among the sham-injured controls, the data were pooled and analyzed as one group (designated as SHAM).

Motor: beam-balance and beam-walk

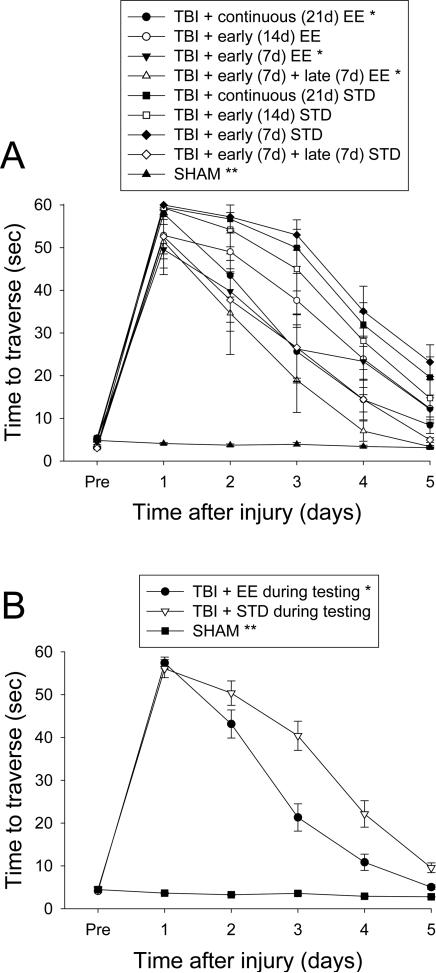

All rats were capable of balancing on the beam and as such no pre-surgical differences were observed among groups. Similarly, there were no significant differences among groups in time to traverse the beam prior to injury. However, after the cortical impact significant impairments were detected in both BB and BW tasks for all TBI groups vs. SHAM controls. No statistical differences were observed on BB ability among the TBI groups post-injury regardless of EE temporal manipulation [p > 0.0014, data not shown]. However, as depicted in Fig. 2A, being in the enriched environment during BW testing improved motor ability as revealed by the TBI + continuous EE, TBI + early (7d) EE group, and the TBI + early (7d) + late (7d) EE group traversing the beam significantly faster than the TBI + continuous (21d) STD group and TBI + early (14d) STD group, both of which were in STD housing [p's < 0.0014]. No other group comparisons were statistically significant at the Bonferroni/Dunn level. A subsequent analysis of pooled STD vs. EE conditions during the BW testing revealed that animals in the EE performed significantly better than those in STD conditions [p = 0.0006; Fig. 2B].

Fig. 2.

Mean (± S.E.M.) walking ability as measured by time (sec) to traverse an elevated wooden beam. A) *p < 0.0014 vs. TBI + continuous (21d) STD and TBI + early (14d) STD. **p < 0.0001 vs. all TBI groups. No other comparisons were statistically significant. B) Pooled data for EE and STD groups. *p = 0.0006 vs. TBI + STD. **p < 0.0001 vs. TBI + EE and TBI + STD.

Cognitive: acquisition of spatial learning

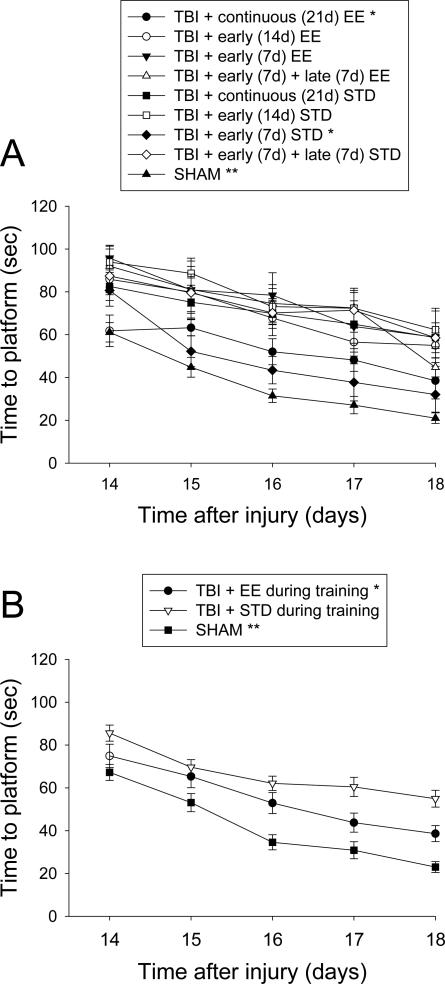

Analysis of spatial learning revealed significant group [F8,93 = 9.066, p < 0.0001] and day [F4,372 = 40.786, p < 0.0001] effects. All TBI groups were significantly impaired relative to the SHAM controls, which were quite proficient in performing the task over the testing period. As depicted in Fig. 3A, exposure to the enriched environment during training facilitated the acquisition of spatial learning as evidenced by shorter times to locate the escape platform in the TBI + continuous EE and TBI + early (7d) STD groups vs. the TBI + continuous STD, TBI + early (7d) + late (7d) STD, TBI + early (14d) STD, and TBI + early (7d) + late (7d) EE groups [p's < 0.0001]. No other group comparisons were statistically significant at the Bonferroni/Dunn level. A subsequent analysis of pooled STD vs. EE groups during water maze training revealed that animals in the EE performed significantly better than those in STD conditions [p = 0.0010; Fig. 3B].

Fig. 3.

Mean (± S.E.M.) time (sec) to locate a hidden (submerged) platform in a water maze. A) *p < 0.0001 vs. TBI + continuous (21d) STD, TBI + early (7d) + late (7d) STD, TBI + early (14d) STD, and TBI + early (7d) + late (7d) EE. **p < 0.0001 vs. all TBI groups. No other comparisons were statistically significant. B) Pooled data for EE and STD groups. *p = 0.0010 vs. TBI + STD. **p < 0.0001 vs. TBI + EE and TBI + STD.

Cognitive: swim speed and visible platform

No significant differences in swim speed (range = 27.5 ± 1.1 cm/sec to 33.6 ± 1.3 cm/sec) or visible platform acquisition were observed among the TBI groups vs. SHAM controls, suggesting that the accurate assessment of place learning was not precluded by extraneous factors, such as motor or visual disparities.

Discussion

Studies from our laboratory and others have shown, unequivocally, that EE is a robust therapeutic approach for experimental brain trauma when provided daily during behavioral assessments 1-6. The current study is a replication, and significant extension, of a previous report 4 that assessed whether the EE-mediated beneficial effects on recovery after TBI are contingent on continuous exposure to EE or if abbreviated enrichment prior to or during task-specific training is sufficient.

The data showed that BW recovery was facilitated in the continuous EE, early 7-d EE, and early + late EE groups, which were in the enriched environment during motor assessment, relative to the continuous STD and early 14-d STD groups. Although it was expected that all groups in the EE during beam testing would be significantly different from the STD housed animals, the statistical analyses did not reveal this for the early 14-d EE group. The lack of effect may be due to the strictness of the Bonferroni/Dunn posthoc statistical test, which was used to minimize type I errors (i.e., attributing an effect when one is not present) given the multiple group comparisons. However, this level of conservativeness may have produced type II errors (i.e., not attributing an effect when one may have been present). Thus, to clarify the effects of EE or STD housing during BW testing, all the EE groups were pooled and directly compared to the combined STD groups. This straightforward analysis clearly demonstrated that the rats in the enriched environment during testing performed significantly better than the groups in STD housing. Regarding the acquisition of spatial learning, in general the groups that received EE during MWM training performed significantly better than those undergoing training while in STD housing. Specifically, the continuous EE and early (7d) STD groups required shorter times to find the escape platform vs. the continuous STD and early + late STD groups. Like the motor data, there were some groups that did not reach statistical significance due to the many comparisons and thus the groups were again pooled into EE or STD housing during maze training. As delineated in Fig. 2B, the EE animals were significantly better than the STD, suggesting that the benefits of EE are task-specific, which replicates our previous preliminary study 4.

The data also revealed that in addition to EE exposure during training, the duration of enrichment is also an important factor for the EE-mediated benefits. This conclusion is derived from the finding that the early (7d) STD group, which was exposed to enrichment for a total of 14 days (i.e., 1 week prior to and during maze training) performed significantly better than the early (14d) STD group that was transferred to EE just as the acquisition of spatial learning began. This finding indicates that a certain threshold of enrichment is necessary to elicit neurobehavioral recovery. Furthermore, the similar rate of learning between the continuous EE group, which received 21 days of enrichment and the early (7d) STD group that received 14 days of EE suggests that 2 weeks of exposure is sufficient to confer learning benefits. However, the facilitated acquisition of spatial learning in the early (7d) STD group relative to the early (7d) and late (7D) EE group, both of which received 14 days of enrichment, but the later accumulated the total in one week intervals separated by a week of STD housing, suggests that the 2 weeks of enrichment must be provided contiguously. The finding may indicate that the neural plastic changes or molecules, such as hippocampal neurogenesis and increased expression of nerve growth factor or synaptophysin, which are known to be mediated by EE 12-20 may require consistent exposure leading up to and during the training to induce and maintain functional benefits.

The overall findings suggest that an interaction between EE and neurobehavioral training is important for recovery and thus supports the hypothesis. This finding also supports the validity of EE as a rehabilitation-relevant model. The parallel can be appreciated when one considers that the cognitive and physical training as well as the social integration that make up a multidisciplinary rehabilitation setting, and which are thought to provide an enriching environment for patients are the same components that have been found to be critical to the EE-mediated benefits after experimental TBI 1. Furthermore, during the rehabilitation phase of recovery, pharmacological agents may act in synergy with the rehabilitation program in promoting recovery. Examples of this regimen in the laboratory include the use of d-amphetamine, which enhances motor performance in TBI rats when beam-walking (i.e., relevant experience) is contiguous with the period of drug action 21, but not if the pharmacotherapy is provided to rats without BW experience. A similar finding is observed after a single dose of methylphenidate coupled with several rehabilitation trials (i.e., BW) 22. A more recent study showed that EE combined with the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT attenuates the loss of TBI-induced choline acetyltransferase-positive medial septal cells, which suggests that histopathology can also benefit from a rehabilitation paradigm 23.

In conclusion, EE is a robust, non-invasive therapeutic strategy that enhances neurobehavioral recovery after experimental TBI. The current data indicate that EE does not have to be initiated immediately after TBI for successful promotion of cognitive recovery. This is an important finding given that most pharmacologic 24-29 and non-pharmacologic approaches 30-32 require relatively early initiation for therapeutic efficacy. This study provides a clearer understanding of the importance of initiation and duration of EE and may have important implications for clinical rehabilitation programs.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health grants HD046700 and NS060005 awarded to AEK.

Support: This work was supported by NIH grants HD046700 and NS060005 (AEK) There are no conflicts of interest to report

References

- 1.Sozda CN, Hoffman AN, Olsen AS, Cheng JP, Zafonte RD, Kline AE. Empirical comparison of typical and atypical environmental enrichment paradigms on functional and histological outcome after experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1047–57. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamm RJ, Temple MD, O'Dell DM, Pike BR, Lyeth BG. Exposure to environmental complexity promotes recovery of cognitive function after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 1996;13:41–7. doi: 10.1089/neu.1996.13.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hicks RR, Zhang L, Atkinson A, Stevenon M. Veneracion M, and Seroogy KB. Environmental enrichment attenuates cognitive deficits, but does not alter neurotrophin gene expression in the hippocampus following lateral fluid percussion brain injury. Neuroscience. 2002;112:631–37. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffman AN, Malena RR, Westergom BP, et al. Environmental enrichment-mediated functional improvement after experimental traumatic brain injury is contingent on task-specific neurobehavioral experience. Neurosci Lett. 2008;431:226–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kline AE, Wagner AK, Westergom BP, et al. Acute treatment with the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT and chronic environmental enrichment confer neurobehavioral benefit after experimental brain trauma. Behav Brain Res. 2007;177:186–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Passineau MJ, Green EJ, Dietrich WD. Therapeutic effects of environmental enrichment on cognitive function and tissue integrity following severe traumatic brain injury in rats. Exp Neurol. 2001;168:373–84. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kline AE, Massucci JL, Dixon CE, Zafonte RD, Bolinger BD. The therapeutic efficacy conferred by the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetralin (8-OH-DPAT) after experimental traumatic brain injury is not mediated by concomitant hypothermia. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:175–85. doi: 10.1089/089771504322778631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon CE, Clifton GL, Lighthall JW, Yaghmai AA, Hayes RL. A controlled cortical impact model of traumatic brain injury in the rat. J Neurosci Meth. 1991;39:253–62. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Meth. 1984;11:47–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamm RJ, Dixon CE, Gbadebo DM, Singha AK, Jenkins LW, Lyeth BG, Hayes RL. Cognitive deficits following traumatic brain injury produced by controlled cortical impact. J Neurotrauma. 1992;9:11–20. doi: 10.1089/neu.1992.9.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheff SW, Baldwin SA, Brown RW, Kraemer PJ. Morris water maze deficits in rats following traumatic brain injury: lateral controlled cortical impact. J Neurotrauma. 1997;14:615–27. doi: 10.1089/neu.1997.14.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frick KM, Fernandez SM. Enrichment enhances spatial memory and increases synaptophysin levels in aged female mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:615–26. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaulke LJ, Horner PJ, Fink AJ, McNamara CL, Hicks RR. Environmental enrichment increases progenitor cell survival in the dentate gyrus following lateral fluid percussion injury. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;141:138–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kempermann G, Kuhn HG, Gage FH. More hippocampal neurons in adult mice living in an enriched environment. Nature. 1997;386:493–95. doi: 10.1038/386493a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krech D, Rosenzweig MR, Bennett EL. Effects of environmental complexity and training on brain chemistry. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1960;53:509–19. doi: 10.1037/h0045402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leggio MG, Mandolesi L, Federico F, Spirito F, Ricci B. Gelfo F, and Petrosini L. Environmental enrichment promotes improved spatial abilities and enhanced dendritic growth in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2005;163:78–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson AK, Eadie BD, Ernst C, Christie BR. Environmental enrichment and voluntary exercise massively increase neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus via dissociable pathways. Hippocampus. 2006;16:250–60. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torasdotter M, Metsis M, Henriksson BG, Winblad B, Mohammed AH. Environmental enrichment results in higher levels of nerve growth factor mRNA in the rat visual cortex and hippocampus. Behav Brain Res. 1998;93:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Praag K, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Neural consequences of environmental enrichment. Nat Rev. 2000;1:191–8. doi: 10.1038/35044558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Will B, Galani R, Kelche C, Rosenweig MR. Recovery from brain injury in animals: relative efficacy of environmental enrichment, physical exercise or formal training (1990-2002). Prog Neurobiol. 2004;72:167–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feeney DM, Gonzalez A, Law WA. Amphetamine, haloperidol, and experience interact to affect rate of recovery after motor cortex injury. Science. 1982;217:855–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7100929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kline AE, Chen MJ, Tso-Olivas DY, Feeney DM. Methylphenidate treatment following ablation-induced hemiplegia in rat: experience during drug action alters effects on recovery of function. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;48:773–79. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kline AE, McAloon RL, Henderson KA, Bansal UK, Ganti BM, Ahmed RH, Gibbs RB, Sozda CA. Evaluation of a combined therapeutic regimen of 8-OH-DPAT and environmental enrichment after experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2010 doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1535. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dixon CE, Ma X, Kline AE, et al. Acute etomidate treatment reduces cognitive deficits and histopathology in traumatic brain injured rats. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2222–7. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000080493.04978.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kokiko ON, Hamm RJ. A review of pharmacological treatments used in experimental models of traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2007;21:259–74. doi: 10.1080/02699050701209964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kline AE, Massucci JL, Ma X, Zafonte RD, Dixon CE. Bromocriptine reduces lipid peroxidation and enhances spatial learning and hippocampal neuron survival in a rodent model of focal brain trauma. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:1712–22. doi: 10.1089/neu.2004.21.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kline AE, Yu J, Horváth E, Marion DW, Dixon CE. The selective 5-HT1A receptor agonist repinotan HCl attenuates histopathology and spatial learning deficits following traumatic brain injury in rats. Neuroscience. 2001;106:547–55. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parton A, Coulthard E, Husain M. Neuropharmacological modulation of cognitive deficits after brain damage. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:675–80. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000189872.54245.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid WM, Hamm RJ. Post-injury atomoxetine treatment improves cognition following experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:248–56. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bramlett HM, Green EJ, Dietrich WD, Busto R, Globus MY, Ginsberg MD. Posttraumatic brain hypothermia provides protection from sensorimotor and cognitive behavioral deficits. J Neurotrauma. 1995;12:289–98. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark RS, Kochanek PM, Marion DW, Schiding JK, White M, Palmer AM, Dekosky ST. Mild posttraumatic hypothermia reduces mortality after severe controlled cortical impact in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:253–61. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199603000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clifton GL, Jiang JY, Lyeth BG, Jenkins LW, Hamm RJ, Hayes RL. Marked protection by moderate hypothermia after experimental traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11:114–21. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]