Abstract

Background

Phages could be an important alternative to antibiotics, especially for treatment of multiresistant bacteria as e.g. Pseudomonas aeruginosa. For an effective use of bacteriophages as antimicrobial agents, it is important to understand phage biology but also genes of the bacterial host essential for phage infection.

Results

We isolated and characterized a lytic Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage, named JG004, and sequenced its genome. Phage JG004 is a lipopolysaccharide specific broad-host-range phage of the Myoviridae phage family. The genome of phage JG004 encodes twelve tRNAs and is highly related to the PAK-P1 phage genome. To investigate phage biology and phage-host interactions, we used transposon mutagenesis of the P. aeruginosa host and identified P. aeruginosa genes, which are essential for phage infection. Analysis of the respective P. aeruginosa mutants revealed several characteristics, such as host receptor and possible spermidine-dependance of phage JG004.

Conclusions

Whole genome sequencing of phage JG004 in combination with identification of P. aeruginosa host genes essential for infection, allowed insights into JG004 biology, revealed possible resistance mechanisms of the host bacterium such as mutations in LPS and spermidine biosynthesis and can also be used to characterize unknown gene products in P. aeruginosa.

Background

Opportunistic pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa are a major health concern due to increased antibiotic resistance [1,2]. Phages could be an alternative to antibiotics, therefore, it is important to investigate phage biology and phage-host interactions [3,4].

Phages are ubiquitous and up to 2.5*108 virus particles have been enumerated per ml in natural water [5] with about 100 million estimated phage species [6]. In August 2010, 586 complete genome sequences of phages were available and among these sequences were 46 sequences of Pseudomonas specific phages (National Center for Biotechnology Information; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/; Bethesda, USA). It was stated that about 75% of all sequenced viral genes share no identity to any gene in databases, therefore, most of the viral diversity is uncharacterized [7]. The amount of sequence information of tailed phages increased dramatically in the last years [8]. Characterization of phages is based on morphology as well as on combined genomic and proteomic approaches [9-12]. Other publications describe the host range of phages, which is important with regard to phage therapy [13-15].

In this work, we characterized a newly isolated P. aeruginosa broad-host-range phage named JG004 on genome level and applied a transposon mutagenesis approach of the respective host bacterium to identify genes in P. aeruginosa, which are essential during phage infection. This approach is fast, provides new insights into phage biology and can be easily adapted for the characterization of other phages.

Results and discussion

Family affiliation

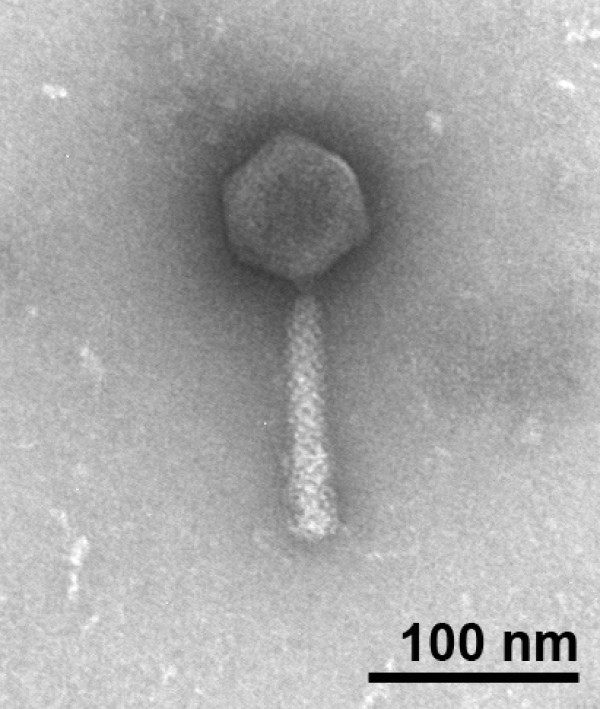

The morphology and size of JG004 phage particles were assessed by transmission electron microscopy (Figure 1), see Methods. In Figure 1, a isometric head structure is visible with a diameter of 67 nm. The contractile tail, which consists of a neck, a contractile sheath and a central tube, has a length of 115 nm. Due to the morphology and the identification of dsDNA by the sensitivity of restriction endonucleases like HindIII (data not shown), JG004 belongs to the familiy Myoviridae. The tailed phages comprise three families: Myoviridae, Siphoviridase as well as Podoviridae. It was stated that 96% of the investigated phages belong to the tailed phages. In particular, there are approximately 499 tailed Pseudomonas phages known, among them 139 from the family Myoviridae [9]. We describe the morphology of phage JG004 together with the comparison of its genome sequence below.

Figure 1.

Morphology of phage JG004. Electron microscopic image of negatively stained phage JG004, which exhibits a contractile sheath and a central tube with a length of 115 nm and a hexagonal head structure with a diameter of 67 nm.

Phage receptor and host range

Determination of the phage receptor was performed as described in the Methods section. Different P. aeruginosa mutant strains which lack flagella (ΔfliM), pili (ΔpilM) or a complete LPS (ΔalgC ) were used to investigate the ability of JG004 to infect these mutant strains. The gene algC encodes an enzyme with phosphoglucomutase and phosphomannomutase activity and is required for the biosynthesis of the complete P. aeruginosa LPS core [16]. The phage JG004 is able to lyse flagella and pili mutants but not the algC mutant defect in LPS biosynthesis, which indicates that LPS is the receptor of JG004.

In order to determine the host range of JG004, we used a set of 19 clinical isolates to investigate the ability of JG004 to infect these strains (Table 1). JG004 is able to infect around 50% of the tested clinical isolates (Table 1), suggesting that JG004 belongs to the broad-host-range phages. Additionally, JG004 is even capable of infecting a P. aeruginosa mucA mutant, which produces large amounts of exopolysaccharides and displayes a mucoid phenotype [17]. Mucoid P. aeruginosa strains are frequently isolated from patients suffering from cystic fibrosis and are correlated with a poor prognosis [18].

Table 1.

Strains and phages used in this study.

| Bacterial strain or phage | Phenotype or genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| PAO1* | Wild type | [54] |

| PA14 | Wild type | [55] |

| PAO1 ΔmucA* | PAO1 mucA::aacC1-gfp GmR | Sabrina Thoma, this laboratory, unpublished |

| PAO1 ΔpilA* | pilA inactivated by allelic displacement; tagged with eGFP, TcR, GmR | [56] |

| PAO1 ΔfliM * | fliM inactivated by allelic displacement; tagged with eGFP, TcR, GmR | [56] |

| PAO1 ΔalgC | algC::aacC1-gfp GmR | Julia Garbe, this laboratory, unpublished |

| BT2, BT72, BT73, RN3, RN43, RN45*, NN84 | Clinical CF isolates | Medical Highschool Hannover, Germany |

| PACF15, PACF21*, PAKL1, | Clinical CF isolates | Gerd Döring, |

| PAKL4*, PACF60*, PACF61*, PACF62, PACF63* | Tübingen, Germany | |

| Nr. 18*, 19*, 26*, 29 | Urinary tract infection isolate | Michael Hogardt, München, Germany |

| JG004 | Wild type PAO1 LPS-specific lytic bacteriophage | This study |

* = strains infected by phage JG004 in the host range and receptor studies.

Abbreviations: GmR, resistant to gentamicin; TcR, resistant to tetracyclin; eGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Growth characteristics

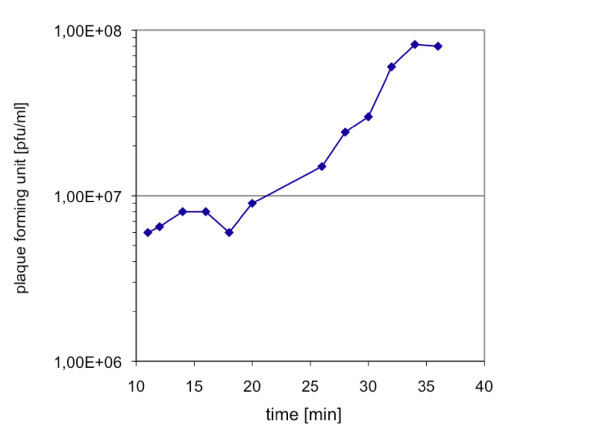

Figure 2 shows the one step growth curve of phage JG004. The burst size, which describes the average number of phages liberated per bacterial cell as well as the latent phase were calculated as described in Methods. JG004 is able to produce approximately 13 progeny phages per cell and has a latent phase of 31 min.

Figure 2.

Growth of JG004. One step growth curve of phage JG004. A representative growth experiment of three independent experiments is shown. Within 34 min, the phage is able to produce about 13 phage progeny per infected cell.

Genome properties and organization

The entire genome sequence of phage JG004 was determined as described in Methods and revealed a genome with a size of 93,017 bp. Detailed inspection of the 454 sequence reads as well as two possible genome assemblies, revealed some interesting features of the JG004 genome. A small part (bases from position 1 to 1238) of the JG004 genome has a twice to three times higher coverage by sequence reads compared to the rest of the genome (Additional file 2, Figure S1). This high coverage could be either an artifact of 454 sequencing or it indicates that this region might be present in multiple copies in the genome as a repetitive sequence. One possible arrangement could be a linear genome, which is flanked with the genome region (bases from 1 to 1238) at both ends. This is supported by the identification of 116 reads, which start exactly at the same position (position 1 in our submitted sequence; Additional file 2, Figure S2). Also, at the end of this part (position 1238), we identified 55 sequence reads which all stop at the same position indicating the endpoint of a linear genome (Additional file 2, Figure S3). This data suggests that the 1238 bp fragment is present at the beginning and the end of the genome.

To verify whether this part of the genome is present in one or multiple copies and to assess the chromosomal structure, we amplified this part of the genome by PCR using primers which bind outside of the putative repetitive sequence at the respective 5' and 3'-flanking regions. Assuming a circular genome we amplified the region using a primer which binds at position 1279 (primer 2; Additional file 2, Figure S4) and one primer which binds at position 92971 (primer 5; Additional file 2, Figure S4). Both primers generated a PCR product of 1300 bp, which corresponds to only one copy of the genome region 1 to 1238, confirming the 454 sequence data (Additional file 2, Figure S4). Moreover, we sequenced the PCR product and again confirmed the 454 sequence data. This result only indicates that the JG004 genome does not contain two consecutive copies of the putative repetitive sequence. The investigation of the linearity of the JG004 genome following treatment with exonuclease Bal31 [19], which degrades only double-stranded linear DNA, gave inconsistent results for the genome of JG004. We decided to integrate only one copy of the region from position 1 to 1238.

Annotation of the JG004 sequence identified 161 putative coding sequences and a GC content of 49.26% (Table 2; Additional file 1, Table S1). The general characteristics of the phage genome are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

General features of the JG004 genome

| Feature | Genome JG004 |

|---|---|

| Genome size | 93,017 bp |

| G+C content (G+C content host) | 49,26% (68%) |

| No. of predicted CDSs | 161 |

| Predicted tRNAs | tRNAGlu; tRNAPhe; tRNAGly; tRNAPro; tRNAAsn; tRNACys; tRNAAsp; tRNAIle; tRNALeu; tRNALys; tRNAArg; tRNAGln |

| % of genome with non-coding regions | 11.3% |

The presence of genes coding for tRNAs was investigated using the tool tRNAscan-SE 1.21 [20]. With this software, we were able to identify twelve tRNAs in the genome of JG004, which are summarized in Table 2 and Additional file 1, Table S1. The presence of tRNA genes is common in members of the Myoviridae phages with large genomes. It was pointed out earlier that tRNA genes in phages are almost always clustered and that they may facilitate a more rapid overall translation rate, especially the translation rate of rare codons [21].

We also searched the JG004 genome for the presence of promoters, terminators and regulatory elements as described in the Methods section. No convincing sigma 70-dependent promoter region was identified in a suitable location using the web service SAK [22]. However, we identified 16 putative rho-independent terminator regions using the TransTermHP software tool [23] (Table 3). All terminators are at the right location downstream of an annotated gene. We also scanned 100 bp of the 5' region of all JG004 ORFs for the presence of conserved motifs using the program MEME [24]. We identified a conserved putative Shine Dalgarno sequence with the consensus AAGGAG (G/A)(A/T) 3-10 nt in front of the predicted ATG start codon of 108 ORFs. This sequence is more closely positioned to the ATG start codon than the Shine Dalgarno sequence in Gram-negative bacteria as e.g. E. coli, which is positioned 7-14 nt to the ATG start. Moreover, we detected two AT rich motifs in front of 6 and 4 CDS, respectively, which may indicate putative phage promoters (Additional file 1, Table S2).

Table 3.

Predicted Terminator sequences.

| Position | Gene | Sequence | Strand | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1682 - 1711 | gene 3 |

GCGTGGTAAAGAGAA GCCCCGGG-CAGC GAAA GCTGATCCCGGGGC TTTTTTATTGCCTTG |

plus | 100 |

| 1711 - 1682 | gene 4 |

CAAGGCAATAAAAAA GCCCCGGGATCAGC TTTC GCTG-CCCGGGGC TTCTCTTTACCACGC |

minus | 93 |

| 5477 - 5462 | gene 12 |

GCGTTGAAAAAGAAA GAGGGC TTTC GCCCTC TGCTGGTATCTAGAG |

plus | 100 |

| 14969 - 14951 | gene 30 |

ACCAAGTGATATAAA GCCCGCC CACAA GGCGGGC TTCTTTGTCTAAGGA |

minus | 95 |

| 31234 - 31251 | gene 64 |

TGCGTAAAGACTTCA GGGAGGC TTCG GCCTCCC TTTCGTCGTAGGAGG |

plus | 93 |

| 35839 - 35864 | gene 71 |

TATGCCACATCGACG GGGAGCTGCCT TAAC GGGTGGCTCCC TTTGTTGTTTCTGGA |

plus | 95 |

| 51300 - 51330 | gene 91 |

AAAACAAGAATAATT AAGCCCCGG-AAGC GAAA GCTTGCCGGGGCTC TTTGTTATGGGTTTT |

plus | 100 |

| 51328 - 51302 | gene 92 |

AACCCATAACAAAGA GCCCCGGCAAGC TTTC GCTT-CCGGGGC TTAATTATTCTTGTT |

minus | 95 |

| 51302 - 51328 | gene 91 |

AACAAGAATAATTAA GCCCCGG-AAGC GAAA GCTTGCCGGGGC TCTTTGTTATGGGTT |

plus | 100 |

| 66578 - 66593 | gene 116 |

CAGTTCTAACCCAAG GGGAGC TTCG GCTCCC TTTTTCATTGGAGAT |

plus | 100 |

| 72492 - 72507 | gene 129 |

GCTTCAATAAGATAA GGGAGC TTCG GCTCCC TTTATTGTATCAAAG |

plus | 93 |

| 76657 - 76683 | gene 133 |

GCATGTAAAATCATT GGCCCGG-GGCT TGAC AGCTTCCGGGCC TTTGTGTATTCTGAG |

plus | 95 |

| 79632 - 79650 | gene 142 |

GACGCCACACTTTCA GCCCGCC CACAA GGCGGGC TTCTTTTTGCCTGAA |

plus | 100 |

| 80739 - 80756 | gene 143 |

CATTATTTTAGAATT GCCCGGC GAGA GCCGGGC TTTTTCGTGGCAGGG |

plus | 100 |

| 87753 - 87785 | gene 162 |

AATGCTGTAAAATAA TGCCCGTTAGGC TGAAATAAT GCTTGACGGGCA TTTTTGTATCTGTAG |

plus | 100 |

| 92215 - 92198 | gene 173 |

TCTTTCCTATGAGAG GCCCCGG TCAC CCGGGGC TTGTTACGGATTGAT |

minus | 93 |

Terminator sequences are shown as displayed by TransTermHP. Each terminator sequence starts with 15 nt of the 5' tail (underlined) followed by the 5' stem, loop, 3' stem and 15 nt of the 3' tail (underlined). Score as provided by TransTermHP, only terminators with a score above 90 are shown.

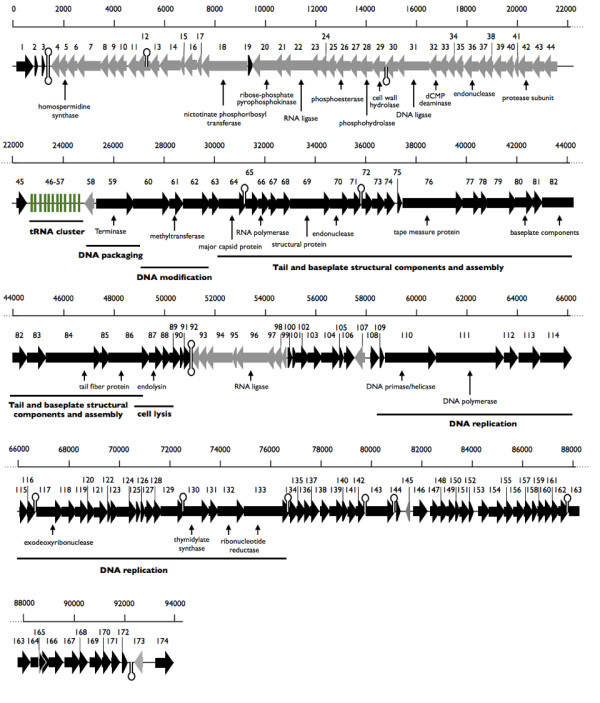

Features of the JG004 genome

A schematic representation of the genome, with its predicted CDSs, the tRNA locations, some functional assignments and overall genetic organization is shown in Figure 3 and Additional file 1, Table S1. The genome of phage JG004 shows 11.3% intergenic space. This is comparable with the genome of the host P. aeruginosa PAO1 which has 10.6% non-coding regions [25]. Putative functions could be assigned to only 30 (18.5%) genes based on sequence similarities (Figure 3). Although phage JG004 and PAK-P1 share strong similarities, we found 19 genes with no similarities to PAK-P1 including 13 genes with no significant similarities to any protein in the database. The proteins with no similarity to other proteins are small proteins with a size between 47 aa and 112 aa. It is still difficult to accurately predict short genes with computational methods [26], therefore, these predictions are uncertain.

Figure 3.

Genome of JG004. Schematic representation of the JG004 genome with its assumed tRNAs, genes and some functional assignments. The arrowheads point in the direction of transcription. Gene 46-57 represent the tRNAs of phage JG004. Predicted terminator structures are indicated as hairloop structures.

No significant match to proteins annotated as integrase, repressor or transposase was found, suggesting that this phage is a virulent phage which is in concordance with the results of the highly related phage PAK-P1 [27].

Gene 66 has similarities to RNA polymerases (e-value: 6e-41) suggesting that the phage JG004 is probably not dependent on the host transcriptional machinery. Moreover, genes encoding for enzymes of the DNA replication machinery were found, suggesting that the DNA replication is also independent from the host. We found genes with similarities to a DNA polymerase (gene 111; e-value: 0.0), a DNA helicase/primase (gene 110; e-value: 0.0), a thymidylate synthetase (gene 130; e-value: 6e-70), a ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase (gene 132, 133; e-values: 0.0) and to a putative exodeoxyribunuclease (gene 117; e-value: 1e-28). A terminase like gene (gene 59; e-value: 0.0) could also be detected. Phage terminases are DNA packaging enzymes and are among the most conserved proteins found in phages. Some terminases also contain endonuclease activity to cut DNA into the genome length of the respective phage [28]. Two putative endonucleases were also detected (gene 36, 70; e-values: 2e-8, 3e-14). Endonucleases could be involved in the DNA packaging process or in host nucleic acid damaging. Interestingly, the putative endonuclease gene 70 has no homologue in phage PAK-P1.

Moreover, one putative methyltransferase was found (gene 61; e-value: 4e-8). Methyltransferases are important for the methylation of DNA to protect the DNA against it's own endonucleases or endonucleases of the host, which serve as a protection against foreign DNA and infection of phages.

Sequence based predictions identified only six genes probably involved in virion morphogenesis: gene 84 and 86 (putative tail fiber proteins; e-values: 2e-153; 1e-105), gene 80 and 82 (putative baseplate components; e-values: 2e-63; 2e-95), gene 69 (putative structural protein; e-value: 1e-93) as well as gene 64, which encode for the major capsid protein (e-value: 0.0). A putative tape measure protein was also detected (gene 76; e-value: 9e-20) close to the putative structural proteins. It was shown for phage T4 that the so called tape measure protein regulates the length of the phage tail [29].

Lysis of phages with dsDNA is accomplished by two proteins, an endolysin, which degrades the peptidoglycan and a holin, which permeabilizes the cytoplasmic membrane to release the endolysin into the periplasm [30]. We found one gene, which shares 98% identity to the endolysin of the Pseudomonas phage PaP1 (gene 87; 6e-102). However, we could not detect any similarities to a holin. This is not unexpected, since holins are very diverse and classified into twelve unrelated orthologous groups [30].

58 putative small proteins with less than 100 amino acids were found in in the genome of phage JG004. None of these small proteins has a predicted function. It was shown before that phage genomes contain small proteins with unknown function [31-33]. It is speculated that these proteins may have a role as accessory factors that bind to and subtly modify the specificity of host proteins so that they function appropriately during phage infection [34].

Interestingly, one hypothetical protein shared a low identity (32%; e-value: 0.32) with a homospermidine synthase (gene 5). We could show that phage JG004 is spermidine-dependent since it is not able to infect a P. aeruginosa mutant with a defect in spermidine synthesis (Table 4; see paragraph transposon mutagenesis). A homospermidine synthase produces homospermidine out of spermidine and putrescine. It is suggested that polyamines like spermidine are important for the DNA charge balance during DNA packaging [35]. The negative charge of the DNA is shielded by the positive charge of the polyamine and allows compact packaging.

Table 4.

Transposon mutants screened with the LPS specific phage JG004.

| Transposon mutant | Integration of transposon | Product name* | Pathway and Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| TM3 | speD (PA0654) | S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase proenzyme | Polyamine biosynthesis (PseudoCyc) |

| TM4 | PA0534 | conserved hypothetical protein | - |

| TM7 | PA0421 | hypothetical protein | - |

| TM12 | wzz2 (PA0938) | hypothetical protein | Involved in O-antigen chain length determination/LPS biosynthesis [57] |

| TM13 | PA2555 | probable AMP-binding enzyme | - |

| TM15 | algC (PA5322) | phosphomannomutase | LPS biosynthesis; alginate biosynthesis [16] |

| TM16 | migA (PA0705) | alpha-1,6-rhamnosyl-transferase | LPS outer core biosynthesis [42] |

| TM17 | rmlA (PA5163) | glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase | LPS biosynthesis [39] |

| TM18 | waaL (PA4999) | O-antigen ligase | LPS biosynthesis [58] |

| TM19 | PA5001 | hypothetical protein | LPS biosynthesis [40] |

| TM20, TM22 | rmlB (PA5161) | dTDP-D-glucose 4,6-dehydratase | LPS biosynthesis [40] |

| TM21 | PA2200 | conserved hypothetical protein | - |

| TM23 | wapR (PA5000) | alpha-1,3-rhamnosyl-transferase WapR | LPS outer core biosynthesis [42] |

Integration of the transposon was identified by arbitrary PCR.* = according to http://www.pseudomonas.com

Similarities of JG004 to other phages

Comparison of the genome with other phage genomes present in databases revealed that phage JG004 is highly related to the recently published phage PAK-P1 [27] with 87% identity on the nucleotide level. A Mauve analysis [36] between JG004 and PAK-P1 identified only few insertions or deletions, see Additional file 2, Figure S5. This suggests that these phages could belong to the same genus within the Myoviridae family.

Using BlastP searches we identified predicted proteins with a sequence identity between 43 to 99% to Pseudomonas phage KPP10 proteins [13] (Additional file 1, Table S1). Although phage KPP10 shares a similar morphology to JG004 with a head size of 72 nm and a tail length of 116 nm, genome alignments revealed that only 8% of the KPP10 genome shares similarities between 66% and 95% to JG004. Clearly, despite some morphological similarities, the genome sequence does not indicate any close relationship. In addition to phage PAK-P1 and to a lesser extent to phage KPP10, no significant genome sequence homology to other phages has been observed. The major capsid protein of JG004 shares 100% identity to the major capsid protein of PAK-P1 and as described by Debarbieux et al. [27], 33% identity to the major capsid protein of the Salmonella phage FelixO1 [27]. While JG004 and FelixO1 seem related regarding the size of phage head and tail structures (FelixO1 head: 70 nm, tail 138 nm) we did not detect any significant similarity to phage FelixO1 or related phages as Erwinia phage phiEa21-4 or Enterobacteria phage WV8 on the genome level. However, we identified four proteins with an identity from 27 to 49% to another orphan phage: Escherichia phage rv5 with no apparent relative [37]. Again no significant similarity on the genome level was observed. The same observation was made for the widespread PB1-like phages 14-1, F8, LBL3, LMA2, PB1 and SN. Although the phages have a similar morphology (head diameter: 74 nm; tail length: 140 nm; [38]), the genomes of these phages share no significant similarity to phage JG004.

Transposon mutagenesis

We screened a random P. aeruginosa transposon library to identify P. aeruginosa genes essential for infection by phage JG004. A mixture of random transposon P. aeruginosa mutants were infected by phage JG004 (see Material and Methods). Only P. aeruginosa mutants, which contained a mutation in a gene essential for phage infection, survived the phage treatment. These strains were isolated and the genomic position of the mariner transposon was identified by arbitrary PCR (Table 4). A total of approximately 30000 transposon mutants were screened and 14 phage resistant mutants were isolated and analyzed. Since two mutants, TM20 and TM22 are defect in the same gene, rmlB, a total of 13 genes was identified, which are essential for phage infection.

The transposon screen revealed genes important for LPS biosynthesis (see Table 4 for details) like the gene algC which is needed for a complete LPS core in P. aeruginosa [16]. It also revealed the genes rmlA and rmlB, which are involved in the biosynthesis of the LPS core sugars [39,40]. These findings confirm that the phage JG004 uses LPS as receptor. Other identified genes involved in LPS biosynthesis are wzz2, waaL, migA, PA5000 and PA5001 (Table 4) [40].

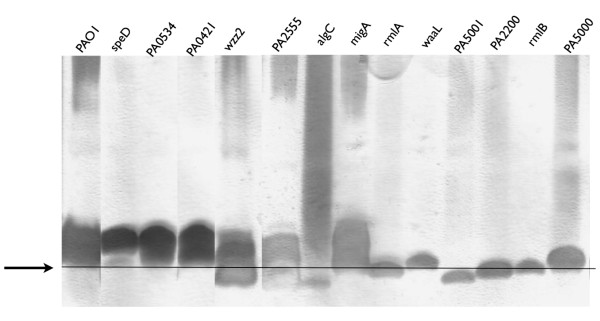

Since nine out of 13 identified genes encoded proteins involved in LPS biosynthesis, we additionally isolated LPS from all mutant strains and analyzed it by electrophoresis (see Materials and Methods). Figure 4 shows the LPS profiles of the transposon mutants. The lipid A, which migrates furthest due to its size, is seen as a dark grey spot at the end of the gel. The migration depends on changes in the LPS composition, mostly in the core polysaccharide which is adjacent to the lipid A [41]. Not all LPS biosynthesis genes cause changes in the LPS which are visible by electrophorsis e.g. migA [42], which appears as wild type LPS. The black line in Figure 4 indicates the migration level of the wild type lipid A. Dramatic changes in the LPS profile which differs clearly from the P. aeruginosa wild type LPS can be seen for the algC, the wzz2 and the PA5001 mutant. Further analysis of the LPS for example Western blot analysis with antibodies specific to the different components of the LPS could provide a better understanding of the mutants, but was not involved in this phage characterization study.

Figure 4.

LPS profile of transposon mutants. Silver stained SDS-PAGE illustrating the isolated LPS of the wild type PAO1 and the transposon mutants. Only the gene, interrupted by the transposon of the respective mutant is indicated on top of the lanes, PAO1 is the P. aeruginosa wild type. The arrow points to the black line in the lower part of the gel. This line indicates the migration of wild type lipid A and core sugars of the LPS [42]. As indicated, the LPS of the speD, PA0534, PA0421, PA2555 and migA mutant strains appears similar to wild type LPS. The LPS profile of the remaining mutant strains is different and indicates an altered LPS structure. Interestingly, the biochemical analysis of LPS indicates that gene PA2200 might be involved in biosynthesis or modification of P. aeruginosa LPS due to altered migration.

We also identified genes essential for phage infection, which encode proteins of unknown function. The gene PA0421 encodes a protein with a weak similarity to an amine oxidase, the gene PA0534 encodes again a conserved hypothetical protein with an FAD binding domain, PA2555 encodes a putative acetate-CoA ligase and gene PA2200 encodes a conserved hypothetical protein with an EAL domain, which indicates that this protein could hydrolyze the signal molecule cyclic-di-GMP (http://www.pseudomonas.com). However, the role of these proteins during phage infection is unclear and is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

The gene PA0654 encodes the SpeD protein, an S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase, which is an essential part of the spermidine biosynthesis pathway in P. aeruginosa [43]. These results suggest that the infection process of phage JG004 is dependent on spermidine. As pointed out earlier, JG004 also possesses a probable homospermidine synthase, which uses spermidine and purtrescine to synthesize homospermidine. Spermidine itself or homospermidine could be important substances essential for compact packaging of phage DNA by balancing the negative charge of the DNA [35].

The analysis of P. aeruginosa transposon mutants resistant to phage infection confirmed that phage JG004 recognizes LPS as receptor. Moreover, this approach revealed details of phage JG004 biology, e.g. its dependance on spermidine.

Conclusions

We characterized a P. aeruginosa specific broad-host-range phage which is a member of the Myoviridae phage family. JG004 has a contractile sheath and a central tube with a length of 115 nm and an isometric head structure with a diameter of 67 nm. JG004 uses LPS as receptor and has a burst size of 13 phage particles. Genome analysis revealed that this phage shares 87% identity to phage PAK-P1. Despite its morphological similarity to other phages, no significant identity to other phage genomes was detected.

We used a transposon mutagenesis approach of the host to identify genes important for phage infection. This approach indicated a dependance of JG004 on spermidine production of the host bacterium and confirmed LPS as host receptor. In addition to the characterization of host-phage biology, this approach could be an interesting tool to perform host receptor studies or to investigate genes of unknown function such as e.g. P. aeruginosa genes involved in LPS biosynthesis.

Methods

Bacterial strains

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. aeruginosa strains were routinely grown in Luria Bertani (LB) broth medium aerobically at 37°C.

Transposon mutagenesis

Transposon mutagenesis was performed with the mariner transposon as previously described [44] with the following modifications. After incubation of the mating mixture, the cells were scraped and resuspended in 1 ml LB. For selection of P. aeruginosa strains resistant to phage infection, the cells were incubated with a ten fold excess of the phage JG004 for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were plated on LB medium containing 200 μg/ml gentamicin and 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol for the inhibition of the E. coli S17λpir strain. The insertion of the transposon was identified by arbitrary PCR and sequencing as described previously [45].

Phage Isolation

Phages were isolated from sewage following a simple enrichment procedure. Samples from a sewage plant Steinhof in Braunschweig, Germany were centrifuged for 5 min at 4100 × g (Biofuge Fresco, Heraeus). Ten ml of the supernatant was mixed with 5 ml of a P. aeruginosa overnight culture and incubated in 50 ml LB broth at room temperature. After an incubation of 48 h, the cells were sedimented by centrifugation at 4100 × g (Biofuge fresco) for 10 min and the supernatant was transferred to a clean tube. To kill the remaining bacteria, several drops of chloroform were added to the supernatant and the emulsion was mixed for 30 s. To separate the phages, appropriate dilutions of the phage lysate were spotted onto bacterial lawns of top-agar plates. Top-agar plates were produced by adding approximately 5 × 108 cells/ml of P. aeruginosa from an overnight LB broth to 3.5 ml of LB top-agar (0.75%). The inoculated top-agar was overlaid on an LB agar plate and allowed to solidify. After incubation at 37°C for 10 to 16 h, zones of lysis were monitored. Single plaques, derived from a single phage, were separated by stinging with a pipette tip into the plaque followed by resuspending the phages in SM buffer (100 mM NaCl, 8 mM MgSO4, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). Five consecutive single plaque isolates were processed for a pure culture, which was verified by electron microscopy. The resulting phage lysate was concentrated for further analysis using polyethylenglycol and stored at 4°C.

Electron microscopy

The morphology of the phages was determined by negative staining with 2% uranyl acetate (pH 4.8) and transmission electron microscopy. Phages were allowed to absorb onto a thin carbon film, prepared on mica, from a liquid sample for different time points, washed in TE buffer (10 mM TRIS, 2 mM EDTA, pH 6.9) and distilled water. Phages were negatively stained by floating the carbon film for appr. 15 sec on a drop of 2% aqueous uranyl acetate. Then, the carbon film was picked up with copper grids (300 mesh), blotted semi-dry with filter paper (Macherey-Nagel, MN615, 90 mm, Düren, Germany) and subsequently air dried. Samples were examined in a Zeiss EM910 transmission electron microsope at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV and calibrated using 30 nm gold particles at a magnification of 63.000. Images were recorded digitally with a Slow-Scan CCD-Camera (ProScan, 1024 × 1024, Scheuring, Germany) with ITEM-Software (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions, Münster, Germany). Brightness and contrast were adjusted with Adobe Photoshop CS3.

Determination of host range of phage JG004

To determine the phage host range, top-agar plates with the potential host lawn were prepared. Top-agar plates were produced by adding approximately 5 × 108 cells/ml of P. aeruginosa from an overnight LB broth to 3.5 ml of LB top agar (0.75%). Ten μl of a phage stock solution were spotted on the top-agar plate and incubated at 37°C for 12 to 16 h. After incubation, the appearance of the lysis zones at the site where the phage suspension was added, was examined. Each phage was tested against each bacterial strain in triplicate in independent experiments. The lysis was categorized as clear (+), turbid (0) and no reaction (-) as described [14].

Phage growth characteristics

To determine phage growth characteristics, such as burst size and duration of the infection cycle, single step growth experiments were performed as previously described for phage JG024 [46]. The burst size was determined as: (phage titer at the end of the single step growth curve at time point 34 min minus phage titer at time point 11 min) divided by phage titer at time point 11 min. The latent phase was estimated at the midpoint of the exponential phase of a one step growth experiment [47,48].

Sequencing, analysis and annotation of phage genome

To isolate phage DNA, phages were propagated in top-agar plates as described above. After growth at 37°C the plates were overlayed with 10 ml SM buffer and incubated with shaking at 4°C for 4 h. The supernatant was filtrated (0.22 μm) and stored at 4°C. Phage DNA was isolated using the Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) Lambda Kit according to manufacturer's instructions. Ten ml phage lysate with a titer of at least 1010 phages/ml were used to isolate up to 1 μg/ μl pure phage DNA. Digestion with restriction endonucleases was done following the protocols of the manufacturer.

Whole genome sequencing of the phage JG024 was done at the McGill University and Génome Québec Innovation Centre (Montréal, QC, Canada) using the Genome Sequencer FLX and 454 Technology. A total of 19294 reads with an average length of 344 bases was assembled to one single contig with a 67-fold coverage. The annotation of the unknown phage genes was done by using the software GeneMark.HMM [26]. The Heuristic approach of GeneMark was used to identify genes in small genomes under 100 kb. The identified genes were compared with the NCBI ORF Finder [49]. Nucleotide sequences were scanned for homologues using the Basic Alignment Search Tool (blastx) [50]. To search for tRNA genes in the phage genome sequence, the internet tool tRNAscan-SE 1.21 [20] was used. Results were compared with the phage PAK-P1 annotation. Sequence comparison was conducted using ClustalW2 online analysis tool [51]. Investigation of the codon usage was performed using a software tool based on JCat [52]. The genome sequence as well as the annotation is deposited at GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information) using the following accession number: GU988610.

Verification of genome ends

To verify the genome ends, we amplified approximately 1300 bp of the ends of the genome by PCR and sequenced the PCR products using sequencing service of GATC Biotech (Konstanz, Germany). 30 ng genomic DNA of JG004 (see above) were used as a template in a standard PCR using TrueStart Taq polymerase (Fermentas AB, Helsingborg, Sweden) and primers described in Additional file 2, Fig. S4. The PCR products were separated on 1% TAE agarose and stained with SYBR safe (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany) to verify the size. Before sequencing, the PCR products were purified using QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Isolation and analysis of LPS

LPS was isolated and analyzed by a two-buffer tricine-based SDS-PAGE system. The isolation of the LPS was performed as described previously [16]. The SDS-PAGE consists of a 4% stacking gel and a 16.5% separating gel. Before analysis by SDS-PAGE, an aliquot of the LPS sample was combined with an equal volume of 2 × sample buffer (0.2% bromophenol blue, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 40% glycerol, 3.3% SDS and 100 mM Tris HCL, pH6.8) and heated to 95°C for 5 min. Before silver staining with 0.1% silver nitrate, the gels were incubated in acetic acid for 30 min. After 5 min washing in dH2O, the gels were developed in 2.5% sodium carbonate, 0.1% formaldehyde, 0.001% sodiumthiosulfate for 2-5 min. To stop the reaction, the gels were transferred into a 2% glycine, 0.5% EDTA solution.

Identification of promoter regions, terminator structures and other motifs

The genome of phage JG004 was scanned for the presence of putative sigma 70-dependent promoter regions using the web service SAK [22]. Putative promoter regions with a score above 1 were scanned for the presence of conserved -10 and -35 regions using the Virtual Footprint software [53] and for their genomic location, orientation and vicinity to the next gene. No promoter was identified matching these criteria. Rho-independent terminator structures were identified using the TransTermHP software tool [23]. Only rho-independent terminators at the correct genomic location with a score above 90 are displayed. Definition of the score is described in [23]. The program MEME was used for identification of conserved intergenic motifs in phage JG004 [24].

Authors' contributions

JG designed the study and performed the experiments. BB assisted with bioinformatics knowledge and reassembled the JG004 genome sequence. Electron microscopically examinations were done by MR. MS designed the study, did bioinformatic analyses and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1 and S2. S1: Genes of phage JG004 and their predicted function. S1: Predicted position of putative phage promoter.

Supplementary Figures. Contains Supplementary Figures S1 to S5.

Contributor Information

Julia Garbe, Email: julia.garbe@med.lu.se.

Boyke Bunk, Email: b.bunk@tu-bs.de.

Manfred Rohde, Email: manfred.rohde@helmholtz-hzi.de.

Max Schobert, Email: m.schobert@tu-bs.de.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gerd Doering, Burkhard Tuemmler and Michael Hogardt for providing clinical P. aeruginosa strains. Richard Muench helped with the TransTermHP analysis. We thank Dr. Elizabeth Murphy for proofreading. JG was supported by the DFG-European Graduate College 653.

References

- Strateva T, Yordanov D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa - a phenomenon of bacterial resistance. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:1133–1148. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.009142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livermore DM. Has the era of untreatable infections arrived? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64(Suppl 1):i29–36. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skurnik M, Strauch E. Phage therapy: facts and fiction. Int J Med Microbiol. 2006;296:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers WC. Bacteriophage therapy. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:437–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergh O, Børsheim KY, Bratbak G, Heldal M. High abundance of viruses found in aquatic environments. Nature. 1989;340:467–468. doi: 10.1038/340467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohwer F. Global phage diversity. Cell. 2003;113:141. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart M, Rohwer F. Here a virus, there a virus, everywhere the same virus? Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens SR. Comparative genomics and evolution of the tailed-bacteriophages. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann HW. 5500 Phages examined in the electron microscope. Arch Virol. 2007;152:227–243. doi: 10.1007/s00705-006-0849-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan T, Liu J, DuBow M, Gros P, Pelletier J. The complete genomes and proteomes of 27 Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5174–5179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501140102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulakov LA, N KV, Shlyapnikov MG, Kochetkov VV, Del Casale A, Allen CCR, Larkin MJ, Ceyssens PJ, Lavigne R. Genomes of "phiKMV-like viruses" of Pseudomonas aeruginosa contain localized single-strand interruptions. Virology. 2009;391:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceyssens PJ, Noben JP, Ackermann HW, Verhaegen J, De Vos D, Pirnay JP, Merabishvili M, Vaneechoutte M, Chibeu A, Volckaert G, Lavigne R. Survey of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its phages: de novo peptide sequencing as a novel tool to assess the diversity of worldwide collected viruses. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:1303–1313. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama J, Maeda Y, Takemura I, Chess-Williams R, Wakiguchi H, Matsuzaki S. Blood kinetics of four intraperitoneally administered therapeutic candidate bacteriophages in healthy and neutropenic mice. Microbiol Immunol. 2009;53:301–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2009.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knezevic P, Kostanjsek R, Obreht D, Petrovic O. Isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa specific phages with broad activity spectra. Curr Microbiol. 2009;59:173–180. doi: 10.1007/s00284-009-9417-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma V, Harjai K, Chhibber S. Characterization of a T7-like lytic bacteriophage of Klebsiella pneumoniae B5055: a potential therapeutic agent. Curr Microbiol. 2009;59:274–281. doi: 10.1007/s00284-009-9430-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne MJ, Russell KS, Coyle CL, Goldberg JB. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa algC gene encodes phosphoglucomutase, required for the synthesis of a complete lipopolysaccharide core. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3500–3507. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3500-3507.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DW, Schurr MJ, Mudd MH, Govan JR, Holloway BW, Deretic V. Mechanism of conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8377–8381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govan JR, Deretic V. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:539–574. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.539-574.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loessner MJ, Inman RB, Lauer P, Calendar R. Complete nucleotide sequence, molecular analysis and genome structure of bacteriophage A118 of Listeria monocytogenes: implications for phage evolution. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:324–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropinski AM, Sibbald MJ. Transfer RNA genes and their significance to codon usage in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa lamboid bacteriophage D3. Can J Microbiol. 1999;45:791–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon L, Chervonenkis AY, Gammerman AJ, Shahmuradov IA, Solovyev VV. Sequence alignment kernel for recognition of promoter regions. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1964–1971. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsford CL, Ayanbule K, Salzberg SL. Rapid, accurate, computational discovery of Rho-independent transcription terminators illuminates their relationship to DNA uptake. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R22. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1994;2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, Brinkman FS, Hufnagle WO, Kowalik DJ, Lagrou M, Garber RL, Goltry L, Tolentino E, Westbrock-Wadman S, Yuan Y, Brody LL, Coulter SN, Folger KR, Kas A, Larbig K, Lim R, Smith K, Spencer D, Wong GK, Wu Z, Paulsen IT, Reizer J, Saier MH, Hancock RE, Lory S, Olson MV. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature. 2000;406:959–964. doi: 10.1038/35023079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besemer J, Borodovsky M. Heuristic approach to deriving models for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3911–3920. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debarbieux L, Leduc D, Maura D, Morello E, Criscuolo A, Grossi O, Balloy V, Touqui L. Bacteriophages can treat and prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infections. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1096–1101. doi: 10.1086/651135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VB, Feiss M. The bacteriophage DNA packaging motor. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:647–681. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuladze NK, Gingery M, Tsai J, Eiserling FA. Tail length determination in bacteriophage T4. Virology. 1994;199:301–310. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young I, Wang I, Roof WD. Phages will out: strategies of host cell lysis. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:120–128. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ES, Heidelberg JF, Eisen JA, Nelson WC, Durkin AS, Ciecko A, Feldblyum TV, White O, Paulsen IT, Nierman WC, Lee J, Szczypinski B, Fraser CM. Complete genome sequence of the broad-host-range vibriophage KVP40: comparative genomics of a T4-related bacteriophage. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:5220–5233. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.17.5220-5233.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceyssens PJ, Lavigne R, Mattheus W, Chibeu A, Hertveldt K, Mast J, Robben J, Volckaert G. Genomic analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phages LKD16 and LKA1: establishment of the phiKMV subgroup within the T7 supergroup. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6924–6931. doi: 10.1128/JB.00831-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigele PR, Pope WH, Pedulla ML, Houtz JM, Smith AL, Conway JF, King J, Hatfull GF, Lawrence JG, Hendrix RW. Genomic and structural analysis of Syn9, a cyanophage infecting marine Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:1675–1695. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann NH, Clokie MRJ, Millard A, Cook A, Wilson WH, Wheatley PJ, Letarov A, Krisch HM. The genome of S-PM2, a "photosynthetic" T4-type bacteriophage that infects marine Synechococcus strains. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3188–3200. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.3188-3200.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu TY, Schaefer J. REDOR NMR characterization of DNA packaging in bacteriophage T4. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:1031–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling ACE, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne R, Darius P, Summer EJ, Seto D, Mahadevan P, Nilsson AS, Ackermann HW, Kropinski AM. Classification of Myoviridae bacteriophages using protein sequence similarity. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceyssens P, Miroshnikov K, Mattheus W, Krylov V, Robben J, Noben J, Vanderschraeghe S, Sykilinda N, Kropinski A, Volckaert G, Mesyanzhinov V, Lavigne R. Comparative analysis of the widespread and conserved PB1-like viruses infecting Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:2874–2883. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenfeldt W, Giraud MF, Leonard G, Rahim R, Creuzenet C, Lam JS, Naismith JH. The purification, crystallization and preliminary structural characterization of glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase (RmlA), the first enzyme of the dTDP-L-rhamnose synthesis pathway from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:1501–1504. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900010040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J, Kocíncová D, Westman E, Lam J. Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Innate immun. 2009;15:261–312. doi: 10.1177/1753425909106436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau P, Lindhout T, Beveridge T, Dutcher J, Lam J. Differential lipopolysaccharide core capping leads to quantitative and correlated modifications of mechanical and structural properties in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6618–6631. doi: 10.1128/JB.00698-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon KKH, Westman EL, Vinogradov E, Jin S, Lam JS. Functional characterization of MigA and WapR: putative rhamnosyltransferases involved in outer core oligosaccharide biosynthesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1857–1865. doi: 10.1128/JB.01546-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou HT, Kwon DH, Hegazy M, Lu CD. Transcriptome analysis of agmatine and putrescine catabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1966–1967. doi: 10.1128/JB.01804-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulasekara HD, Ventre I, Kulasekara BR, Lazdunski A, Filloux A, Lory S. A novel two-component system controls the expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa flmbrial cup genes. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:368–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole GA, Kolter R. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:449–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbe J, Wesche A, Bunk B, Kazmierczak M, Selezska K, Rohde C, Sikorski J, Rohde M, Jahn D, Schobert M. Characterization of JG024, a Pseudomonas aeruginosa PB1-like broad host range phage under simulated infection conditions. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:301. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajunen M, Kiljunen S, Skurnik M. Bacteriophage phiYeO3-12, specific for Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:3, is related to coliphages T3 and T7. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5114–5120. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.18.5114-5120.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moineau S, Durmaz E, Pandian S, Klaenhammer TR. Differentiation of Two Abortive Mechanisms by Using Monoclonal Antibodies Directed toward Lactococcal Bacteriophage Capsid Proteins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:208–212. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.1.208-212.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DL, Church DM, Federhen S, Lash AE, Madden TL, Pontius JU, Schuler GD, Schriml LM, Sequeira E, Tatusova TA, Wagner L. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:28–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote A, Hiller K, Scheer M, Münch R, Nörtemann B, Hempel DC, Jahn D. JCat: a novel tool to adapt codon usage of a target gene to its potential expression host. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W526–531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münch R, Hiller K, Grote A, Scheer M, Klein J, Schobert M, Jahn D. Virtual Footprint and PRODORIC: an integrative framework for regulon prediction in prokaryotes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4187–4189. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn NW, Holloway BW. Pleiotrophy of p-uorophenylalanine-resistant and antibiotic hypersensitive mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Genet Res. 1971;18:185–197. doi: 10.1017/S0016672300012593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahme LG, Stevens EJ, Wolfort SF, Shao J, Tompkins RG, Ausubel FM. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science. 1995;268:1899–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.7604262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausen M, Heydorn A, Ragas P, Lambertsen L, Aaes-Jørgensen A, Molin S, Tolker-Nielsen T. Biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa wild type, flagella and type IV pili mutants. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1511–1524. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels C, Griffiths C, Cowles B, Lam JS. Pseudomonas aeruginosa O-antigen chain length is determined before ligation to lipid A core. Environ Microbiol. 2002;4:883–897. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abeyrathne PD, Daniels C, Poon KKH, Matewish MJ, Lam JS. Functional characterization of WaaL, a ligase associated with linking O-antigen polysaccharide to the core of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3002–3012. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.3002-3012.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1 and S2. S1: Genes of phage JG004 and their predicted function. S1: Predicted position of putative phage promoter.

Supplementary Figures. Contains Supplementary Figures S1 to S5.