Abstract

To demonstrate how Community Advisory Boards (CABs) can best integrate community perspectives with scientific knowledge and involve community in disseminating HIV knowledge, this paper provides a case study exploring the structure and dynamic process of a “Community Collaborative Board” (CCB). We use the term CCB to emphasize collaboration over advisement. The CCB membership, structure and dynamics are informed by theory and research. The CCB is affiliated with Columbia University School of Social Work and its original membership included 30 members. CCB was built using six systematized steps meant to engage members in procedural and substantive research roles. Steps: (1) Engaging membership, (2) Developing relationships, (3) Exchanging information, (4) Negotiation and decision-making, (5) Retaining membership, and (6) Studying dynamic process. This model requires that all meetings be audio-taped to capture CCB dynamics. Using transcribed meeting data, we have identified group dynamics that help the CCB accomplish its objectives: 1) dialectic process helps exchange of information; 2) mutual support helps members work together despite social and professional differences; and 3) problem solving helps members achieve consensus. These dynamics also help members attain knowledge about HIV treatment and prevention and disseminate HIV-related knowledge. CABs can be purposeful in their use of group dynamics, narrow the knowledge gap between researchers and community partners, prepare members for procedural and substantive research roles, and retain community partners.

Keywords: Community-Based Participatory Research, Community Advisory Boards, group dynamics, HIV research

Community partners on Community Advisory Boards (CABs) have been traditionally involved in procedural aspects of research: advising on recruitment strategies; gaining entry to the community; and communicating risks and benefits to participants (Cox, Rouff, Svendsen, Markowitz, & Abrams, 1998; Morin et al., 2008; Strauss et al., 2001). However, a set of principles of Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) exist encouraging researchers to expand community involvement in substantive aspects of research: specification of aims; data collection, analysis and interpretation; and dissemination (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). CBPR has prompted a flourishing of CABs whose members – service providers and consumers, agency administrators – are involved in all aspects of research (Israel et al., 2006; McKay, Pinto, Bannon, & Guillamo-Ramos, 2007; Pinto, McKay, & Escobar-Chavez, 2008). However, disparate degrees of knowledge about HIV and research methods undermine CAB utility and retention of members. Retention can be improved by addressing members’ wishes to gain HIV knowledge and disseminate it in their communities (Cargo et al., 2008; Cox et al., 1998; Morin et al., 2008; Pinto, 2009). Regrettably, what CAB dynamics facilitate integration of science-based knowledge with community perspectives remain unknown.

This paper provides a case study exploring the structure and dynamic process of a “Community Collaborative Board” (CCB). We use this term to emphasize collaboration over advisement. Excerpts from board meetings will illustrate the integration of community and science-based knowledge and plans for disseminating HIV knowledge.

CCB STRUCTURE & PROCEDURES

To describe CAB roles, previous studies have relied on board members’ interviews at the end of a single study (Cox et al., 1998; Morin, Maiorana, Koester, Sheon, & Richards, 2003). Contrastingly, to capture group dynamics as they occur and evaluate their usefulness, this CCB audio records all meetings. This CCB involves community partners in procedural and substantive aspects of research. We draw on the Theory of Balance and Coordination (Litwak, Meyer, & Hollister, 1977), suggesting that it is necessary to balance scientific and experiential knowledge so that researchers and community partners may match diverse skills with research tasks. This CCB is grounded in two models of collaboration. One model is parent-focused and aims to design, implement and test interventions (McKay, Hibbert et al., 2007; McKay, Pinto et al., 2007). The other model was developed by the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies (HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies, 2010) to provide input in clinical trials.

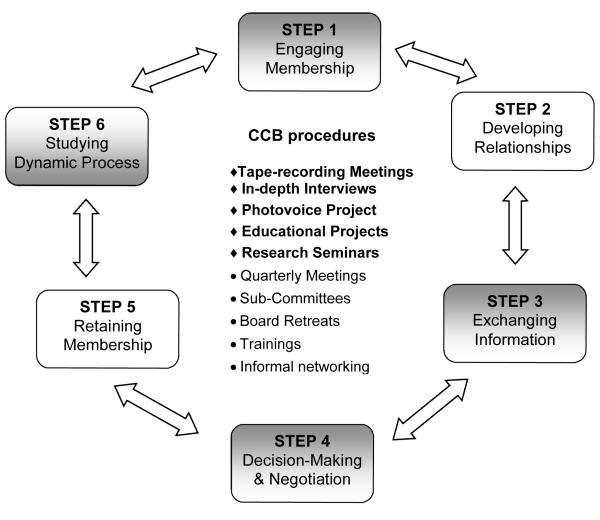

We based this CCB on triangulated different types of data (Denzin, 1989). We used as background information 12 interviews with members of the two boards above. To promote researcher-researcher, community-researcher and community-community collaborations, both models involved cross sections of community and researcher representation. Figure 1 shows CCB structure and procedures in six recursive steps: Engaging Membership; Developing Relationships; Exchanging information; Negotiation and Decision-Making; Retaining Membership; and Studying Dynamic Process. Steps represented by shaded boxes are unique to this CCB, as are highlighted procedures.

Figure 1. CCB structure and procedures.

Note: The models in which this CCB is grounded, involve a broad cross section of community and researcher representation.

Engaging Membership required the use of a purposive solicitation of 30 individuals. The initial group of four researchers recommended community partners with whom they had served on other CABs. Initial partners were known to at least two researchers, who in turn recommended service consumers and providers. Some board members knew one another from different professional networks. This helped create stronger links than single relationships would have created. Initial CCB members included eight behavioral researchers, one doctoral student, two post-doctoral fellows, one director of field education, eight providers, five administrators, one pastor, and four consumers. Nineteen were females and 11 males. Nine were African-American, seven Latino/a, nine Caucasian, two Asian/Pacific Islander, and three multi-ethnic/racial. Ages ranged from 33 to 60.

Developing Relationships occur during quarterly and sub-committee meetings, retreats, seminars, informal interactions via electronic correspondence, phone calls, and social events. Relationships rely on exchange of social support – e.g., researchers assist providers to prepare presentations for conferences; providers make referrals for consumers; and all members create opportunities to talk about issues affecting our lives. During meetings, all members educate one another about the networks with which they are associated and bring resources from these networks – e.g., Requests for Proposals. We socialize around social/cultural activities and often discuss what we expect from one another.

Exchanging Information occurs at meetings where presentations are made by board members and guests. We have engaged in educational projects, including a Photovoice, in which members documented with photographs the strengths and challenges faced by their communities. This type of project helps us develop research goals. By capitalizing on existing relationships, some members have dedicated time to building trust with members not previously known to them. Members demonstrate trust by disclosing personal information, sharing resources and partnering in grant writing. We value our diverse knowledge equally and express it, for example, in our Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) and vision statement: “to close the gap of health disparities in our communities and to improve individual well being through community-based participatory research.” This vision highlights the knowledge/skills community partners lend to scientific research (Popay & Williams, 1996).

Decision-Making & Negotiation is advanced by information exchange, a sharing of social influence that generates new ideas. The CCB is unique in its decision-making because it uses recorded data from previous meetings to evaluate and modify how members share power and solve problems. For example, the project described below grew out of community partners’ recommendations. While the first author serves as the chair of most meetings, several members have served as co-chairs. Prior to each meeting, the CCB coordinator requests agenda items from all members. Those who submit items lead corresponding discussions in meetings.

Retaining Membership requires sub-committees to oversee CCB procedures. Activities that help retain membership include informal gatherings, workshops on research designs and on data analysis/interpretation. We provide stipends to all members other than researchers at each meeting. These stipends come from the grant that generated this study. Meeting attendance varies based upon members’ availability. We optimize attendance by alternating evening and morning meetings. Approximately, two thirds of members attend all quarterly and sub-committee meetings. However, all members receive minutes of all meetings. To capture CCB dynamics, we audio-record and transcribe all meetings and make these available to all members.

Studying Dynamic Process concerns the use of meeting data to evaluate CCB process, identify helpful dynamics, and plan future work. This step of the model is the main focus of this paper and is therefore illustrated below. To demonstrate the integration of CCB members’ diverse knowledge, we used excerpts from meetings.

GROUP DYNAMICS IN CCB PROJECTS

Group dynamics – equitable participation, open communication, committee work – promote collective action, address conflicts and engender trust (Becker, Israel, & Allen III, 2005; Breton, 1990; Steinberg, 1997). For example, during a quarterly meeting, members proposed to address how HIV prevention methods could be used by providers to bridge research to practice. We devoted two meetings to this issue, in which researchers presented summaries of science-based prevention methods. After presentations, facilitators encouraged discussion about how HIV prevention knowledge could be bridged to practice, what science-based information was most useful to communities and what strategies could be used to educate consumers. Discussions revealed three group dynamics (below) that have helped us fulfill our goals to integrate community perspectives with science-based knowledge and to disseminate HIV knowledge.

Methods and procedures

Approval from the appropriate Institutional Review Board was received to collect audio recordings of meetings (four hours altogether). Using transcriptions, three coders developed a coding scheme independently. Exchanges between CCB members were coded to capture group dynamics. Coders met to review, discuss and integrate codes. This iterative approach is recommended for capturing themes that emerge from data representing consensus among coders (Beebe, 1995). Text was coded that included CCB members’ exchange of information, social support and solutions to agreed-upon issues. These themes were identified based on Shulman’s group dynamics (Shulman, 1992). Coders achieved 100% concordance on the passages below. After the analysis was completed, members were asked to review results and provide interpretations and feedback. Recommendations were integrated throughout the paper.

Incorporating community perspectives in HIV research and practice

Dialectic process was characterized by exchange of knowledge and experiences. This discussion was sparked by a woman who identifies as a service consumer living with HIV. She said this about her health care provider:

I’m learning a whole lot here … if only could I get this information at my doctor’s office … but my doctor doesn’t tell me how to protect my husband who is HIV-negative.

Encouraged by this statement, a researcher reflected:

I ask for an HIV test every year when I see my gynecologist and she thinks I’m paranoid. She doesn’t want to test me because she says, ‘Aren’t you married?’ She thinks because I am a white married woman I don’t need a test, and that I’m paranoid for asking.

Some members observed that, as providers serving HIV-positive individuals, many lacked HIV knowledge to educate clients. The following exchange shows how a dialectic process helped develop CCB members’ HIV knowledge.

Provider #1: I don’t understand how antiretroviral drugs are a prevention method. How would meds make me less infectious?

Researcher #1: The meds prevent replication of the virus.

Provider #2: But it’s not a vaccine. Think of it more as a chemical barrier.

Provider #3: But if you stop taking it you will become vulnerable.

Researcher #2: How many of us actually know how antiretroviral medication works?

Researcher #1: We need to study this further … for now; we need to know that meds help decrease the likelihood of transmission by lowering the amount of HIV in the blood.

All agreed that, by focusing on primary prevention, providers might overlook HIV-positive individuals’ need of secondary prevention. Some researchers responded as this one did:

I wonder if what’s on the table is “HIV-phobia” … speaking in terms of primary prevention as if that’s the most important thing. I wonder if our board’s focus on primary prevention reflects HIV stigma. We have to be aware that what we are talking about is stigma. AIDS is a stigmatized illness different from other diseases.

Mutual support was characterized by members’ willingness to support one another despite their differences. Social support helped members reveal their fears about HIV, recognize HIV stigma, and ponder how fear and stigma may affect providers’ incorporation of HIV knowledge into practice. One provider said:

My white blood cell count has been low for many years… and although it may indicate HIV in my body, I have been reluctant to take the test. If one is reluctant, how can we possibly integrate this into our services and help clients get tested?

From this point forward, the discussion focused on mutual support as a way for addressing structural barriers – homophobia, heterosexism and racism. A provider reflected:

How do you bring to practice topics of racism, sexism, and classism? How do we bring that into an individualized HIV intervention and help consumers see how society is unequal? How do we support one another to change those inequities?

An agency administrator prompted the board to generate solutions.

The emotions behind what we say are present in how we respond to consumers. That is why self-reflection is so needed to support our work. And what other solutions may we come up with?

CCB members observed that providers’ self-reflection may foretell the incorporation of prevention methods into services being provided in community settings. Self-reflection was suggested as a strategy for confronting fears and biases.

We need to look at ourselves. What about if transmitting HIV prevention knowledge is making me uncomfortable? If I am uncomfortable, I don’t use what I know the same way. (Provider)

This issue is related to the provider’s knowledge, as are issues regarding race, class, gender … that the work really begins with the provider, as opposed to looking at the consumer … self-reflection, that’s an intervention in and of itself in relationship to integrating HIV prevention into practice. (Administrator)

Board cohesion was fostered when a consumer suggested that CCB members get HIV tests. Getting tested with support from the group, he suggested, might help providers and researchers further face their fears and biases.

I would like to recommend an assignment for this board. I would like everybody to have an HIV test. I think you should put yourself in the other person’s shoes [consumers]. I’d like for someone to come back and share that experience.

Problem solving was characterized by CCB members’ collective work toward solutions to agreed-upon issues. Members discussed which science-based methods could be consistently used to educate consumers. They agreed on three methods – condom use, HIV testing and medication adherence. Participants felt that these methods could be implemented by building clients’ personal capacities.

We’re hosting our first health fair. People will come to an area where they can sit down, talk about issues and get tested for HIV. By witnessing community leaders, such as me changing their behaviors and getting tested, others can move beyond their fears and phobias. (Pastor)

In terms of discussion, it really complicates things. Simplification is difficult around medication. We have medication groups and education and I’m working with an occupational therapist to better develop strategies to talk about medication properly. (Provider)

All agreed that, in addition to these solutions, providers must examine structural barriers impeding HIV prevention.

Just teaching people how to avoid HIV is not enough, unless we also address disparities, racism and other issues that have profound impacts on how people protect themselves. (Researcher)

I would say age is important because when you talk to some younger gentlemen, they say, “You know what? AIDS is treatable now.” Younger people believe that older people are not having sex, and even providers may think so. (Consumer)

Disseminating HIV knowledge

Dialectic process encouraged members to use their social and professional positions to facilitate dissemination of knowledge. Some members represent organizations serving populations most affected by HIV. CCB members have authority to change agency policy and practice. They can promote HIV prevention by incorporating research into services they provide and by encouraging the practitioners they supervise to do the same. One administrator said:

It’s pathetic, because I used to be an HIV counselor and here I am saying, “It’s not my job.” It shows me how far away I’ve gotten from the things that matter to me. I want to do more, and will take this information to the people I supervise.

CCB members have influence among their neighbors, who view them as role models. Members have agreed to spread the knowledge generated through this project.

I work sometimes with the people in my building. Someone brought up the discussion about a little girl having HIV. So I brought it up to their attention, “What’s the problem?” I helped the girls and boys write a record about how to prevent getting HIV. Next time I see them they have to sing this rap song that they made up about preventing HIV. (Consumer)

Researchers agreed to build capacity by infusing participatory strategies into their classes to encourage providers to use HIV knowledge in practice. One researcher commented:

This type of structured discussion has been so helpful… I will try a similar process in my classes and teach my students how to overcome the barriers we identified here. This is important because my students are already providing services in their internships.

CCB providers are committed to educate fellow providers on incorporating HIV prevention in practice.

One of the reasons I am here is to take what I’m learning back to my agency. This has been such a rich discussion that helped me with my struggle as to how to address HIV issues in this terrible economic environment. (Provider and agency administrator)

LESSONS LEARNED

The CCB is committed to co-author publications and disseminate lessons learned. We have taken lessons we learned to researchers and communities through presentations – e.g., NIH-sponsored training institutes: Community-Partnered Suicide Prevention, Rochester, New York, 2008 and Winter Research Institute on CBPR, San Jose, California, 2010. In the Winter Institute, experts agreed that publishing CCB dynamics could help other collaborators replicate and evaluate their endeavors (C. Cerulli, N. Wallerstein, A. M. White, and J. Wiley). The Box below summarizes key lessons learned.

Lessons Learned from Developing a Community Collaborative Board: Structure, Procedures, Outputs and Outcomes.

Is the CCB model replicable?

◆ The systematic collection and analysis of different types of data used in this study make this CCB model replicable. The entire CCB model or parts of it have been used by researchers and community partners in Portland, OR; Rochester, NY; Newark, NJ; and both Brazil and Mongolia. Knowing that CAB dynamics require researchers and community partners to engage in dialectic processes, mutual support and problem solving will help CCB members choose to engage in group dynamics shown to facilitate the processes and outcomes discussed here. Grounded in this CCB, researchers will be better able to use group dynamics to build capacity and to accomplish the procedures needed to maintain a board and retain its membership.

Has the structure (e.g., voting and membership requirements) of this CCB changed over time?

◆ Decisions about this CCB’s structure have been made over time through negotiation and consensus. These are documented in our vision statement and a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). Any suggested change has been reviewed by the board during quarterly meetings. Changes are made based on consensus. This egalitarian process is helped by capitalizing on the group dynamics discussed above.

How has this CCB membership change over time and defined self-governance?

◆ The membership has been continuous; with only five out of 30 members having terminated participation. In exit interviews, they said that they were changing jobs and/or moving to another city. Our members have attended at least two quarterly meetings per year, been involved in at least one sub-committee, and participated in at least one educational project per year. Members have been engaged in developing the MOU for governance procedures. Opportunities for informal networking include retreats and time before and after meetings scheduled in advance in order to promote attendance.

Has this CCB governance been hierarchical and CCB members also involved in other networks?

◆ Initial CCB members knew each other from other professional networks. To engage new members, we relied on our professional relationships. This helped us identify individuals with a track record in CBPR and/or who had the capacity to engage with community members and disseminate research findings. Recruiting CCB members among individuals in several networks has fostered gender, racial/ethnic and intellectual diversity among board members. The leadership of the CCB is moved around the group, in order to encourage power-sharing among diverse individuals. Though the PI of the CCB grant continues to provide guidance, governance has a flat structure characterized by members having equal voting rights on any decision made by the board.

How does this CCB encourage power sharing around racism, sexism, classism, and stigma?

◆ Discussions related to these issues are initiated during meetings where members identify concerns and vent frustrations. CCBs should encourage members to speak honestly about sensitive issues while recognizing the difficulty of doing so. Discussions should be facilitated by different members to allow for power sharing. Especial attention must be paid to members reticent to speak about these topics. In order to capture the phenomenon of power sharing around these issues, we have plans to conduct a self-study.

What has been the role of monetary stipends to this CCB’s success?

◆ Stipends help generate better involvement in research-related endeavors. In our experience, monetary stipends have been essential to the CCB’s success. Involvement with the CCB requires members to incur costs, including transportation to and from meetings, parking, child care and others. Especially in urban areas, these costs can add up to large sums of money, making it impossible, especially for low-income community members, to participate in CCBs. Without stipends to defray these expenses, it would be more difficult to retain members.

What outcomes/outputs has the CCB completed in the past three years?

◆ The CCB has been involved in activities designed to build capacity and accomplish research outcomes/outputs. The CCB has engaged in a Photovoice project designed to help us develop our vision statement and MOU. Having a model with recursive and flexible steps to follow may help provide the structure needed for optimum functioning of CCBs. We have written grant proposals that have been funded. Other examples include written materials for disseminating research findings at the community level. Capacity building includes skill development through trainings, networking and presenting at conferences.

The CCB is a network of diverse individuals with common concerns and goals. To avoid attrition, we identified potential members from professional networks with similar visions. All invited members joined the CCB. We thus recommend the recruitment of individuals who have existing professional relationships. We have had disagreements around research design and types of grants (federal or foundation) to pursue. Disagreements are resolved through negotiation and consensus building. Disagreement is a functional group process, mediated by meeting facilitators, and which is resolved by capitalizing on these dynamics: dialectic process; mutual support; and problem solving. We capitalize on trusting relationships to promote, rather than curtail, dialogue. We have learned that sub-committees with diverse representations yield better integration of diverse knowledge in grant proposals and publications. Working in different committees allows each of us to wait for the next opportunity to realize research projects and designs we each prefer.

The research projects with which we are engaged and their corresponding outputs are originate in quarterly meetings. Members suggest projects grounded in their personal and professional opinions, and the group decides whether to take on such projects. Outputs – e.g., fact sheets and peer reviewed papers – reflect the values of all members. We recommend that CCBs develop in the short-term oral and written agreements about their visions and goals. As research projects unfold, dissemination of research findings in the form of community forums, fact sheets and electronic bulletins is highly recommended.

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge, this is the first time in the literature that CAB structure and dynamics have been theoretically and empirically explicated. This CCB has capitalized on group dynamics to integrate scientific with experiential knowledge, help community partners become educated and involved in HIV research and dissemination. Dialectic process has advanced exchange of information; mutual support has helped members work together despite social and professional differences; and problem solving has helped members achieve consensus.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all members of the Community Collaborative Board (CCB) who participated in this study, who graciously took time from their very busy schedules to help advance knowledge about collaborative research. We acknowledge the outstanding feedback we received on earlier drafts of this paper by Liliane C. Windsor, Doug Warn, Juan David Gastolomendo, Kim Burke and Fatima Hafiz-Wahid.

The CCB is supported by a grant from Columbia University Diversity Program Research Fellowship (Principal Investigator: Rogério M. Pinto, Ph.D.)

Dr. Pinto wrote this manuscript supported by a National Institute of Mental Health Mentored Research Development Award (K01MH081787-02).

When this manuscript was written, Dr. Valera was a postdoctoral fellow supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH19139, Behavioral Sciences Research in HIV Infection; Principal Investigator: Anke A. Ehrhardt, Ph.D.) at the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies (P30 MH 43520; Center Director: Anke A. Ehrhardt, Ph.D.).

REFERENCES

- Becker AB, Israel BA, Allen AJ., III . Strategies and Techniques for Effective Group Process in CBPR. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Shulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community-based Participatory Research for Health. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; San Francisco: 2005. pp. 52–72. [Google Scholar]

- Beebe J. Basic concepts and techniques of rapid appraisal. Human Organization. 1995;54(1):42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Breton M. Learning from social group work traditions. Social Work with Groups. 1990;13:21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cargo M, Delormier T, Levesque L, Horn-Miller K, McComber A, Macaulay AC. Can the democratic ideal of participatory research be achieved? An inside look at an academic-indigenous community partnership. Health Education Research. 2008;23(5):904–914. doi: 10.1093/her/cym077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LE, Rouff JR, Svendsen KH, Markowitz M, Abrams DI. Community Advisory Boards: Their role in AIDS clinical trials. Health and Social Work. 1998;23(4):290–297. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.4.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK. Interpretive Interactionism. Vol. 16. SAGE Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies, C. U. 2010 http://www.hivcenternyc.org/.2010, from http://www.hivcenternyc.org/

- Israel BA, Krieger JW, Vlahov D, Ciske SJ, Foley M, Fortin P. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: Lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City, and Seattle Urban Research Centers. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PM, Israel B, Schulz AJ, Reyes A. Methods for Social Epidemiology. Jossey Bass and J. Turner; San Francisco: 2005. Community-Based Participatory Research: Rationale and relevance for social epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- Litwak E, Meyer HJ, Hollister CD. The role of linkage mechanisms between bureaucracies and families: Education and health as empirical cases in point. In: Lievert RJ, Immershein AW, editors. Power, Paradigms, and Community Research. Sage Publications; Beverly Hills, CA: 1977. pp. 121–152. [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Hibbert R, Lawrence R, Miranda A, Paikoff R, Bell C, et al. Creating mechanisms for meaningful collaboration between members of urban communities and university-based HIV prevention researchers. Social Work in Mental Health. 2007;5:147–168. doi: 10.1300/J200v05n01_07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Pinto RM, Bannon JWM, Guillamo-Ramos V. Understanding motivators and challenges to involving urban parents as collaborators in HIV prevention research efforts. Health and Social Work. 2007;5:169–185. doi: 10.1300/J200v05n01_08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin SF, Maiorana A, Koester KA, Sheon NM, Richards TN. Community consultation in HIV prevention research: A study of community advisory boards at 6 research sites. JAIDS. 2003;33:513–520. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin SF, Morfit S, Maiorana A, Armrattana A, Goicochea P, Mutsambi JM, et al. Building community partnerships: Case studies of Community Advisory Boards at research sites in Peru, Zimbabwe, and Thailand. Clinical Trials. 2008;5(2):147–157. doi: 10.1177/1740774508090211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto RM. Community perspectives on factors that influence collaboration in public health research. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36:930–947. doi: 10.1177/1090198108328328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto RM, McKay MM, Escobar-Chavez C. “You’ve gotta know the community”: Minority women make recommendation about community-focused health research. Women and Health. 2008;47:83–104. doi: 10.1300/J013v47n01_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J, Williams G. Public health research and lay knowledge. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;42(5):759–768. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman L. The Skills of Helping Individuals, Families, Groups and Communities. Brooks Cole; Belmont, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg D. A mutual-aid approach to working with groups: Helping people help each other. Jason Aronson, Inc.; Northvale, NJ: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss RP, Sengupta S, Quinn SC, Goeppinger J, Spaulding C, Kegeles S, et al. The Role of Community Advisory Boards: Involving Communities in the Informed Consent Process. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(12):1938–1943. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]