Abstract

Objectives:

This study aimed to assess the incidence and trend of childhood leukaemia in Basrah.

Methods:

This was a hospital-based cancer registry study carried out at the Pediatric Oncology Ward, Maternity & Children’s Hospital and other institutes in Basrah, Iraq. All children with leukaemia, aged 0 to 14 years diagnosed and registered in Basrah from January 2004 to December 2009 were included in the study. Their records were retrieved and studied. The pattern of childhood leukaemia by year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, morphological subtypes, and geographical distribution was analysed. Rates of childhood leukaemia over time were calculated for six years using standard linear regression.

Results:

The total number of cases of childhood leukaemia was 181. The number of cases ranged from 21 in year 1, to 31 in the final year reaching a peak of 39 in 2006. Leukaemia rates did not change over the study period (test for trend was not significant, P = 0.81). The trend line shows a shift towards younger children (less than 5 years). The commonest types of leukaemia were acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), then acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and finally chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML).

Conclusion:

Annual rates of childhood leukaemia in Basrah were similar to those in other countries with a trend towards younger children. This raises the question about the effect of environmental catastrophes in the alteration of some specific rates of childhood leukaemia, rather than the overall incidence rate. There is a need for further epidemiological studies to understand the aetiology of childhood leukaemia in Basrah.

Keywords: Childhood leukemia, Incidence, Time trend, Cancer registry study, Basrah, Iraq

Advances in Knowledge

This article is based on one of many studies by the Basrah Cancer Research Group and looks at the time trends and geographical distribution of childhood leukaemia in Basrah.

Although the rates of leukaemia in children aged 0 to 14 years did not change over the 6 year period (possibly because of incomplete cancer registration), the rates were much higher than in other Western and Eastern countries. This may be due to exposure to environmental leukemogens.

Another finding is the shift of the incidence of leukaemia in recent years towards children under 5 years.

The highest average rate of childhood leukaemia is in West and East Basrah, two regions exposed to great environmental pollution during recent decades.

Application to Patient Care

The results of our study are useful for determining the extent of childhood leukaemia in Basrah in recent years.

Comparison of the incidence rates in population groups that differ in exposures permits one to estimate the effect of exposure to a hypothesised factor of interest.

The extent of the time trend and geographical distribution of childhood leukaemia will help in future planning of health care services, drug supplies, and other preventive measures for patients and the general population.

Leukaemia is the most common childhood cancer, accounting for 25% to 35% of the incidence of all childhood cancer among most populations.1,2

The commonest type of childhood leukaemia is acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), which occurs in approximately 80% of leukaemia cases, followed by acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), and a few in other categories.3

The incidence of childhood leukaemia is higher in resource rich countries, ranging from 4.0 to 4.4 per 100,000 per year,4 and lower in less-income countries5 although these variations may reflect a lack of registrations of cancer in low-income countries.6 Studies from different parts of the world have indicated an increase in recent decades in the incidence of childhood leukaemia in some countries,7,8 while rates have stayed largely stable in the USA and Nordic countries.9,10 In most countries, the incidence of childhood leukaemia is higher among boys than girls.11,12 Although the aetiology of most childhood leukaemias is unknown,13 several factors have been associated with the disease, including socioeconomic status,14,15 environmental exposures including ionising radiation and benzene,16 infectious agents,17 and parental exposure risk factors.18,19

Basrah is Iraq’s second largest city and its main port. It is located along the Shatt Al-Arab waterway, approximately 545 km southeast of Baghdad and adjacent to Iran and Kuwait. Basrah is composed of a flat alluvial plain formed by the combined flood plains and deltas of the Tigris, Euphrates, and Shatt Al-Arab rivers. The area surrounding Basrah has substantial petroleum resources with many oil wells. Basrah has been exposed to massive environmental pollution as a consequence of military conflicts and lack of an efficient protective policy from 1980 to 2003. Previous research work and growing impressions among physicians and lay people suggest that childhood leukaemia has increased in Basrah since the second Gulf war.20,21,22

However, these suggestions were criticised for being inadequate proof of a real increase in the risk of childhood leukaemia because of incomplete case registration and/or inaccurate population denominators before 2003. In order to study the subject properly, the Basrah Cancer Research Group (BCRG) was established in 2004. BCRG initiated a project to improve registration, identify risk factors, and improve care. This group has achieved good results in registration of cancer, including childhood leukaemia.23

The purpose of this study was to assess the rates and trends of childhood leukaemia in Basrah, Iraq, from 2004 to 2009. The data reported here can be used for comparison with past figures or future findings.

Methods

The Basrah governorate is divided into five areas congruent to the health sectors established by the Basrah health authorities: City centre, South Basrah, West Basrah North Basrah and East Basrah (see map, Figure 4). Information related to the population of Basrah was based on data available from Basrah Health Authorities, electronic lists and the Statistical Office in Basrah. The authors depended on the information from ration cards to assess the size of the population in Basrah. The ration card system was established from the 1990s to provide basic foodstuffs to Iraqi people during the economic sanctions after the 1991 Gulf War. It is therefore the best way to assess the Basrah population’s size under the prevailing circumstances, because the Iraqi government monitors it carefully for economic reasons. It is renewed annually to take into account migration, death, and births in the population. In comparison with other parts of Iraq, the population in Basrah is more stable and, due to a stable political and economic environment migration is not an important issue.

Figure 4:

Average rates per 100,000 of childhood leukaemia in different areas of Basrah, 2004 – 2009: 1) Basrah City centre, 2) South Basrah, 3) West Basrah, 4) North Basrah, 5) East Basrah.

This hospital-based cancer registry study was based on all new cases of childhood leukaemia which were registered at the Pediatric Oncology Ward of the Basrah Maternity & Children’s Hospital and other institutes, e.g. the main oncology centre in Basrah, the cancer regisration section at the Department of Pathology, College of Medicine University of Basrah, and data from some specialist doctors who keep their own collection of cancer cases as part of their routine clinical work. The research protocol was approved by the Scientific Committee in the Department of Community Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Basrah, in December 2009. The permission of the Directorate of Health in Basrah was obtained prior to the research implementation.

In Basrah, all childhood leukaemia cases are referred to the Pediatric Oncology Ward in Basrah’s Maternity & Children’s Hospital, which is responsible for the treatment and registration of all childhood malignancies in Southern Iraq. Many of the children are treated outside Iraq, but they are diagnosed and registered in Basrah before travelling. Diagnosis was based on the histopathology of the bone marrow and complete blood counts. Two haematologists agreed on all diagnoses, and no changes in diagnostic techniques occurred over the study period. Standard criteria are used to diagnose leukaemia, which for the purpose of this analysis have been divided into acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), acute myeloblastic leukaemia (AML), chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Cases identified by various sources were entered first on Excel spreadsheets in most centres, or identified from their original documents and entered by BCRG on Excel. Then, all the Excel files were merged, matched and checked for any duplications.

All analyses were carried out with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) programme (Version 15.0). Some of the figures were constructed using Excel 2007. Incidence data were reported for each year by dividing the incidence by the population (aged 0–14 years) for each year, then multiplying by 100,000. To assess whether the increase in leukaemia rates over time was statistically significant, we calculated rates for the six years 2004–2009 and used standard linear regression to test whether the slope of the line between each year average rates was different from 0. This method is similar to that used by Linet et al. in their study of the changes in leukaemia rates in the USA.24 Age standardised incidence was derived using the world standard population by the direct method.25

Results

There were 181 cases of leukaemia in children aged 0–14 years registered in Basrah during the six years 2004 to 2009. This represented 46.2 % of the total percentage of cancers among children in Basrah. The number of cases ranged from 21 cases in the first year to 31 cases in the final year and reached a peak of 39 cases in 2006 [Table 1].

Table 1:

Leukaemia rates for children aged 0 to 14 years in Basrah, Iraq, from 2004 to 2009.

| Year | No. of leukaemia casesa | Populationb | Rate per 100,000 population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 21 | 777,709 | 2.70 |

| 2005 | 32 | 837,293 | 3.82 |

| 2006 | 39 | 866,896 | 4.49 |

| 2007 | 27 | 946,377 | 2.85 |

| 2008 | 31 | 971,929 | 3.18 |

| 2009 | 31 | 998,171 | 3.10 |

Note: The data were collected from the cancer registry at the Pediatric Oncology Ward in Basrah Maternity & Children’s Hospital.

Legend:

a = cases of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, acute myeloid leukaemia, and chronic myeloid leukaemia.

b = population aged from 0 to 14 years.

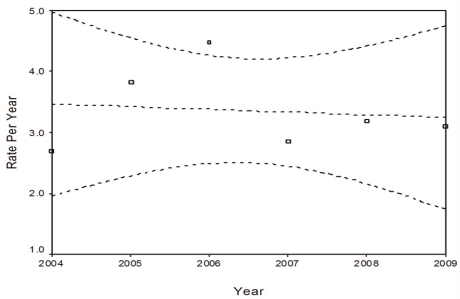

Leukaemia rates in children aged 0 to 14 years did not change over the 6 year period (ratio of 2008–2009 rate to 2004–2005 rate = 0.96; 95% confidence interval = 0.96 – 1.01). By using the parameter estimate from the regression model of untransformed values, it was found that leukaemia rates decreased by 0.123 per 100,000 during the 6 year period: beta (B) = – 0.123; standard error (SE) = 0.17); the test for trend was not significant, with P = 0.81. We were satisfied that presentation of rates in Figure 1 was a robust finding of no change in childhood leukaemia in Basrah over the period of our study.

Figure 1:

Leukaemia rates and 95% confidence intervals among children aged 0 to 14 in Basrah, Iraq, from 2004 to 2009

The total reported cases during the years 2004–2009 shows that leukaemia was more frequent in boys (59.8%) than in girls (40.2%), with a male to female ratio of 149:100. The total leukaemia rate among boys was 3.63 per 100,000 during the years 2004–2005 and 4.18 per 100,000 for 2008–2009. For girls, the rates were 3.03 during the earlier period and 2.07 during the most recent two year period (data not shown).

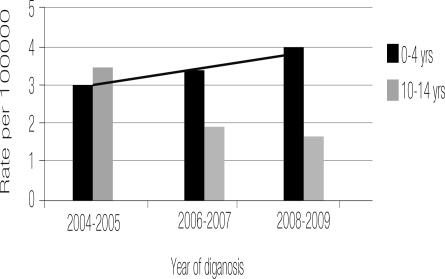

The trend line in Figure 2 shows the shift of the incidence of leukaemia in recent years towards younger children (below 5 years of age). In the 2004–2005 period, children ages 0 through 4 had overall annual leukaemia rates of 3.04 per 100,000, compared with 3.46 for children aged 10 to 14 years. In the 2008–2009 period, children aged 0 to 4 years had an annual rate of 4.36 per 100,000, compared with 1.73 for children aged 10 to 14 years.

Figure 2:

The rates of childhood leukaemia in Basrah, Iraq, according to the age and year of diagnosis.

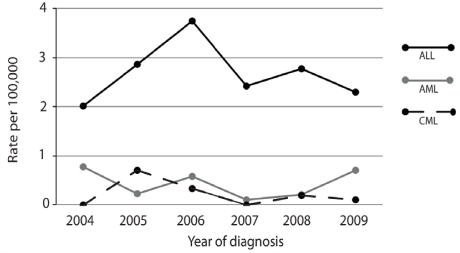

Different trends in incidence were observed for ALL, AML, and CML from 2004 to 2009 [Figure 3]. In the period 2004–2005, there were 40 cases of ALL, 8 cases of AML, and 6 cases of CML. These case number reflect rates of 2.47 per 100,000 children for ALL, 0.49 for AML, 0.37 for CML. During the period 2008–2009, the case counts and rates were 50 for ALL, 9 for AML, and 3 for CML, reflecting rates of 2.53, 0.45, and 0.15 per 100,000, respectively (data not shown).

Figure 3:

The rates of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), and chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) from 2004 to 2009

The rates of childhood leukaemia in each region of Basrah over the five years are shown in Figure 4. The highest rate was found in West Basrah (4.01/100,000), followed by East Basrah (3.88/100,000), North Basrah (3.69/100,000), South Basrah (3.58/100,000), and Basrah city centre (2.77/100,000) respectively.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to describe rates and changes in childhood leukaemia for the population of Basrah, Iraq, in recent years. Data for this study were taken from the cancer registry of the Pediatric Oncology Word of the Maternal & Children’s Hospital in cooperation with the College of Medicine of the University of Basrah and the BCRG.

Basrah is confronted with a range of environmental problems, some of which can be directly linked with the effects of recent military conflicts. Others have been triggered by internal Iraqi policies and actions, and were exacerbated by factors such as the impact of economic sanctions.26

During the 2003 Gulf war, there were reports of oil wells having been deliberately set on fire in the Rumeila oilfield in Basrah, while a thick haze of dark smoke could be seen from Kuwait City the following day. The broad categories of contaminants are volatile hydrocarbons, hydrogen sulphide, and naturally occurring radioactivity. Since the aromatic hydrocarbons (like benzene), which are known to be leukaemogenic, are the most volatile of hydrocarbons, exposure even at low levels can be very harmful.27

Also, in Gulf wars of 1991 and 2003, the US and UK Governments acknowledged that known depleted uranium munitions were used in Iraq. Many tons of this radioactive substance was targeted at the Basrah governorate.28

Our data show that the rates of leukaemia in children aged 0 to 14 years did not change over the 6 year period. This finding is inconsistent with Hagopian et al. study which reported that the average annual incidence of childhood leukaemia in Basrah has raisen substantially.22 In the Hagopian et al. study, the average annual rates of childhood leukaemia were measured by dividing the incidence by the population (aged 0–14 years) for each year, then multiplying by 100,000. The incidence included all new cases of childhood leukaemia that were diagnosed and treated in Basrah (included cases from Basrah and those who came from other provinces in southern Iraq) and divided by the estimated size of the population from Basrah province only; this led to an increase in the average annual rate to about 12 per 100,000. Also, the change in the trend of childhood leukaemia in Hagopian et al. study might be attributed to the underestimation of cancer cases, because of incomplete cancer registration prior to 2003 in Basrah.23

In the present study, leukaemias make up about 46% of paediatric cancers in Basrah, whereas international percentages ranged from 27% of paediatric cancers in the United States, 30% in Ireland and France, 33% in Germany, 35% in Shanghai, China, and India.29–34 The high percentage of leukaemia in the present study may reflect the underestimation of other types of paediatric cancer, or it may be suggest a relatively higher risk of leukaemias in Basrah reflecting an exposure to certain risk factors, like the exposure to environmental leukemogens.

Another finding in the present study is the shift of the incidence of leukaemia in recent years towards younger children (below 5 years of age). Our results are similar to those from the United States and Great Britain,35 where the peak occurs between the age of 2–5 years, but the peak is less marked in less developed countries.36,37 This observation may also be attributed to the effect of environmental pollution and/or the changes in the life style of the population in Basrah in recent years compared to the West.

The highest average rate of childhood leukaemia is present in West and East Basrah. These two regions were exposed to great environmental pollution during recent decades. West Basrah was exposed to many environmental carcinogens in the wars of 1991 and 2003 such as depleted uranium and aromatic hydrocarbons. East Basrah was also affected by environmental pollution as a result of the military conflict in the period from 1980 to 1988, during the Iraq-Iran War.

On the other hand, our data show that the average annual rate of all types of childhood leukaemia (per 100,000 children aged 0 – 14) did not noticeably rise in Basrah during the six years under review. Also, the rates of childhood leukaemia subtypes (ALL, AML, and CML) were not elevated. Because ALL was by far the commonest type, the trends in the rates of all leukaemias combined should mostly reflect trends in the incidence of ALL.

Conclusion

Although we observed no temporal increase in the incidence rates for childhood leukaemia during the 6 year period from 2004 to 2009, there is shift in the incidence of leukaemia in recent years towards younger children and there is an increase in the percentage of childhood leukaemia in comparison with other studies worldwide. This result raises the question about the effect of environmental pollution on the specific characteristics of childhood leukaemia rather than on the overall incidence rate.

It is known that the Basrah region was exposed to environmental insults including the known leukemogen benzene 27 and pyrophoric depleted uranium, 21,28 but also, and still ongoing, undifferentiated water and air pollution; however, no data are available on the doses to which the leukaemia patients in our study were exposed. There is a need for further epidemiological studies to understand the effect of environmental pollution on the pattern of childhood leukaemia in Basrah.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Hans Peer Wagner, Professor of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology (University of Bern, Switzerland) for valuable discussions and for checking the manuscript. We express our appreciation to all the members of BCRG for their continuous effort in updating and improving the data collected.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors reported no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Stiller CA, Draper GJ, Bieber CA. The international incidence of childhood cancer. Int J Cancer. 1988;42:511–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910420408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pui CH, Schrappe M, Ribeiro RC, Niemeyer CM. Childhood and adolescent lymphoid and myeloid leukemia. Hematology. 2004:118–145. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2004.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linet MS, Devesa S, Morgan GJ. The leukemias. In: Schottenfeld D, Joseph F, Fraumeni J, editors. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Oxford; Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 841–871. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkin DM. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. Geneva: World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, International Association of Cancer Registries; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman LS, Edwards BK, Rise LAG, Young JL. Cancer Incidence in Four Member Countries (Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, and Jordan) of the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC) Compared with US SEER. National Cancer Institute. From: . http://seer.cancer.gov/publications/mecc/mecc_monograph.pdf Accessed: April 2007.

- 6.Howard SC, Metzger ML, Wilimas JA, Pui CH, Robison LL, Ribeiro RC. Childhood cancer epidemiology in low-income countries. Cancer. 2008;112:461–472. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hrusak O, Trka J, Zuna J, Polouckova A, Kalina T, Stary J. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia incidence during socioeconomic transition: Selective increase in children from 1 to 4 years. Leukemia. 2002;16:720–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNally RJQ, Eden TOB. An infectious etiology for childhood leukemia: A review of the evidence. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:243–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linet MS, Ries LA, Smith MA, Tarone RE, Devesa SS. Cancer surveillance series: Recent trends in childhood cancer incidence and mortality in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1051– 8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.12.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hjalgrim LL, Rostgaard K, Schmiegelow K, Söderhäll S, Kolmannskog S, Vettenranta K, et al. Age- and sex-specific incidence of childhood leukemia by immunophenotype in the nordic countries. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1539–44. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNally RJ, Rowland D, Roman E, Cartwright RA. Age and sex distributions of hematological malignancies in the U.K. Hematol Oncol. 1997;15:173–189. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1069(199711)15:4<173::aid-hon610>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearce MS, Parker L. Childhood cancer registrations in the developing world: Still more boys than girls. Int J Cancer. 2001;91:402–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1048>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson JR, Gerald PF, Willoughby ML, Armstrong BK. Maternal folate supplementation in pregnancy and protection against acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in childhood: A case-control study. Lancet. 2001;358:1935–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06959-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borugian MJ, Spinelli JJ, Mezei G, Wilkins R, Abanto Z, McBride ML. Childhood leukemia and socioeconomic status in Canada. Epidemiology. 2005;16:526–31. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000164813.46859.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raaschou-Nielsen O, Obel J, Dalton S, Tjønneland A, Hansen J. Socioeconomic status and risk of childhood leukaemia in Denmark. Scand J Public Health. 2004;32:279–86. doi: 10.1080/14034940310022214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belson M, Kingsley B, Holmes A. Risk Factors for Acute Leukemia in Children: A Review. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:138–45. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Infante-Rivard C, Olson E, Jacques L, Ayotte P. Drinking water contaminants and childhood leukemia. Epidemiology. 2001;12:13–19. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fear NT, Simpson J, Roman E. Childhood cancer and social contact: The role of paternal occupation (United Kingdom) Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:1091–7. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez-Saldivar ML, Ortega-Alvarez MC, Fajardo-Gutierrez A, Bernaldez-Rios R, Del Campo-Martinez L, Medina-Sanson A. Father’s occupational exposure to carcinogenic agents and childhood acute leukemia: A new method to assess exposure (a case-control study) BMC Cancer. 2008;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciment J. Iraq blames Gulf war bombing for increase in child cancers. BMJ. 1998;317:1612–15. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yacoub AAH, Al-Sadoon IO, Hassan GG, Al-Hemadi M. Incidence and pattern of malignant disease among children in Basrah with specific reference to leukemia during the period 1990 – 1998. Med J Basrah Univ. 1999;17:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagopian A, Lafta R, Hassan J, Davis S, Mirick D, Takaro T. Trends in childhood leukemia in Basrah, Iraq, 1993–2007. Am J Public Health. From: http://ajph.aphapublications.org/cgi/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2009.164236Accessed: Feb 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Basrah Cancer Research Group . Cancer in Basrah 2005–2008. Basrah: Dar Alkutub for Press & Publication, University of Basrah; 2009. p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linet MS, Ries LA, Smith MA, Tarone RE, Devesa SS. Cancer surveillance series: Recent trends in childhood cancer incidence and mortality in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1051–58. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.12.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyle P, Parkin DM. Statistical methods for registries. In: Jensen OM, Parkin DM, MacLennan R, Muir CS, Skeet RG, editors. Cancer Registration, Principles and Methods. Lyon: IARC; 1991. p. 26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.United Nations Environment Programme . Desk Study on the Environment in Iraq. From: www.unep.org/pdf/iraq Accessed: Feb 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Environment in Iraq . UNEP Progress Report; UN, Geneva: 2003. From: http://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/Iraq_PR.pdf Accessed: Feb 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dyer O. WHO suppressed evidence on effects of depleted uranium; expert says. BMJ. 2006;333:990. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39027.603264.DB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linabery AM, Ross JA. Trends in childhood cancer incidence in the US (1992–2004) Cancer. 2008;112:416–32. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stack M, Walsh PM, Comber H, Ryan CA, O’Lorcain P. Childhood cancer in Ireland: A population-based Study. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:890–7. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.087544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desandes E, Clavel J, Berger C, Bernard JL, Blouin P, De Lumley L, et al. Cancer incidence among children in France, 1990–1999. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;43:749–57. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spix C, Eletr D, Blettner M, Kaatsch P. Temporal trends in the incidence rate of childhood cancer in Germany 1987–2004. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1859–67. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bao PP, Zheng Y, Wang CF, Gu K, Jin F, Lu W. Time trends and characteristics of childhood cancer among children age 0–14 in Shanghai. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53:13–16. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swaminathan R, Rama R, Shanta V. Childhood cancers in Chennai, India, 1990–2001: Incidence and survival. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2607–11. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Margolin JF, Steuber CP, Poplack DG. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 15th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. pp. 538–90. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stiller CA, Parkin DM. Geographic and ethnic variations in the incidence of childhood cancer. Br Med Bull. 1996;52:682–703. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plesko I, Somogyi J, Dimitrova E, Kramaroki Descriptive epidemiology of childhood malignancy in Slovakia. Neoplasm. 1989;36:233–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]