SUMMARY

Mural cells (pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells) provide trophic and structural support to blood vessels. Vascular smooth muscle cells alternate between a synthetic/proliferative state and a differentiated/contractile state, but the dynamic states of pericytes are poorly understood. To explore the cues that regulate mural cell differentiation and homeostasis, we have generated conditional knock-in mice with activating mutations at the PDGFRβ locus. We show that increased PDGFRβ signaling drives cell proliferation and downregulates differentiation genes in aortic vascular smooth muscle. Increased PDGFRβ signaling also induces a battery of immune response genes in pericytes and mesenchymal cells, and inhibits differentiation of white adipocytes. Mural cells are emerging as multipotent progenitors of pathophysiological importance, and we identify PDGFRβ signaling as an important in vivo regulator of their progenitor potential.

Keywords: Pericyte, Vascular Smooth Muscle, Adipose, Immune Response, PDGF

INTRODUCTION

Pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) are collectively called mural cells. They are a heterogeneous class of cells, derived from mesoderm or neural crest, which support and interact with endothelial cells in the blood vessel wall. An important distinction between pericytes and VSMCs is anatomical: pericytes are embedded within the basement membranes of capillaries, venules, and arterioles, while VSMCs are found outside the basement membrane of larger vessels. A second distinction is functional, where VSMCs have well-defined roles in providing strength, resilience, and contraction to large vessels and in repairing vascular injury. In contrast, the roles of pericytes are poorly understood and may include structural support for the microvasculature, signaling to the endothelium to control cell growth or quiescence, regulation of blood-brain barrier homeostasis, and potentially some immune functions. Quiescent VSMCs function through a smooth muscle contractile apparatus but they are not terminally differentiated cells; in response to environmental cues (e.g. vascular injury, inflammation) they have the potential to downregulate their contractile apparatus genes and reenter the cell cycle. Pericytes may possess even greater phenotypic plasticity. They are increasingly viewed as multipotent progenitor cells or mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) with capacity to differentiate into adipocytes, osteoblasts, chondrocytes and other cell types (Crisan et al., 2008). Pericytes and MSC may also regulate immune system homeostasis (da Silva Meirelles et al., 2008). These properties make them potentially useful as a source of adult stem cells for regenerative therapies. Nevertheless, how pericyte or mesenchymal progenitor differentiation is regulated in a physiological context remains unclear. It is important to understand regulatory cues because this could offer new avenues for regenerative medicine and might provide insight on disease processes.

Several key signaling pathways coordinate mural cell/endothelial cell interactions during development, including TGF-β, angiopoietins, sphingosine-1-phosphate, Notch, and platelet derived growth factor-B (PDGF-B) (Armulik et al., 2005). Sprouting endothelial tubes secrete PDGF-B, which signals through the PDGF receptor β (PDGFRβ) expressed in mural cell progenitors. This directs the recruitment and expansion of mural cell progenitors at the site of angiogenesis, until PDGFRβ is downregulated as the vasculature matures. Mice lacking PDGFRβ or PDGF-B die around birth with reduced numbers of VSMCs and organ-specific loss of pericytes, including a 95% reduction in pericytes of the central nervous system (Hellstrom et al., 1999; Leveen et al., 1994; Lindahl et al., 1997; Soriano, 1994). Tissue-specific knock-out of PDGF-B demonstrates that the endothelium is the critical source of ligand for recruiting and expanding PDGFRβ-expressing mural cell progenitors (Bjarnegard et al., 2004). Although mice without PDGFRβ signaling develop some VSMCs, analysis of chimeric embryos with competitive mixtures of wild type and PDGFRβ-deficient cells has demonstrated a quantitative dependence on PDGFRβ for mural cell development (Crosby et al., 1998; Lindahl et al., 1998; Tallquist et al., 2000).

PDGF receptors are receptor tyrosine kinases with an extracellular ligand-binding domain and a cytoplasmic enzymatic domain. The signaling activity of PDGFRs is tightly regulated by an autoinhibitory allosteric conformation, and requires ligand-induced receptor dimerization at the cell surface to alleviate autoinhibition and achieve physiological activity. Once activated, tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptor activates a number of downstream signaling pathways including Ras/MAP kinases, PI3 kinase/AKT, PLC/PKC, and Stats (Heldin and Westermark, 1999). These signaling pathways together have additive effects on development, and the summation of pathway activity downstream of PDGFRβ determines the degree of expansion of mural cell progenitors (Tallquist et al., 2003). Point mutations in PDGFRs have been described that relieve autoinhibition and allow constitutive signaling in the absence of ligand (Chiara et al., 2004; Irusta and DiMaio, 1998; Magnusson et al., 2007). In humans, activating mutations in PDGFRα can cause gastrointestinal stromal tumors (Heinrich et al., 2003). Activating mutations in the mouse PDGFRα lead to connective tissue hyperplasia in embryos and widespread organ fibrosis in adult mice (Olson and Soriano, 2009). In contrast, the developmental and disease consequences of increased PDGFRβ signaling are still an open question. Activating mutations in PDGFRβ might alter the developmental potential of mural cells.

PDGF ligands are expressed in many cell types in the cardiovascular system including endothelial cells, monocytes/macrophages, lymphocytes, and platelets, and aberrant PDGFRβ signaling has been implicated in cardiovascular disease (Andrae et al., 2008; Raines, 2004). With this physiological context as a basis for investigating the consequences of increased PDGFRβ signaling, we created two conditional knock-in alleles expressing mutant PDGFRβ from the endogenous PDGFRβ promoter that are able to be conditionally activated in a tissue-specific manner. We report that PDGFRβ activation opposes the differentiation of aortic VSMC and brain pericytes. By microarray profiling we define the PDGFRβ–induced pericyte phenotype as involved in immune responses, highlighting an inherent potential of microvascular pericytes to mediate inflammatory and immune signaling. We find that PDGFRβ signaling in pericytes or mesenchymal progenitor cells inhibits the differentiation of white adipocytes, providing novel insight on the regulation of mesenchymal progenitor differentiation in a physiological context. The finding that PDGF signaling can induce an immune response in pericytes and influence adipocyte differentiation may promote new approaches for understanding obesity.

RESULTS

Derivation of Knock-in Mice

To explore the role of PDGFRβ signaling, we generated three lines of knock-in mice expressing full-length PDGFRβ cDNAs from the endogenous PDGFRβ promoter. Two lines expressed cDNAs harboring different activating mutations, and a third line expressed wild-type PDGFRβ cDNA as a control. The first mutation (V536A), designated βJ, has been characterized in the Ba/F3 cell line as a mutation conferring constitutive activation (Irusta and DiMaio, 1998). It disrupts a highly conserved juxtamembrane region in type III RTKs that contacts the kinase domain and is important for full autoinhibition (Hubbard, 2004). The second mutation (D849V), designated βK, has been characterized in embryoid bodies as conferring constitutive activation on PDGFRβ (Magnusson et al., 2007). It is located in the kinase domain and is thought to interfere with the inactive conformation of the ATP-binding pocket. Our targeting approach allowed conditional cDNA expression by inserting a lox-stop-lox cassette and a splice acceptor in place of the endogenous exon 2 (Figure S1A). In the absence of Cre recombination, knock-in mice are heterozygous for PDGFRβ and are phenotypically normal (Soriano, 1994). We identified correctly targeted ES cell clones by Southern blot (Figure S1B) and these clones were used to derive germline chimeras for the βWt, βJ and βK strains.

PDGFRβ+/(S)Wt, PDGFRβ+/(S)J and PDGFRβ+/(S)K heterozygous mice that carried the inactivating stop-lox-stop cassette, designated (S), were crossed to epiblast-specific Cre lines (Meox2Cre (Tallquist and Soriano, 2000) or Sox2Cre (Hayashi et al., 2002) to obtain mice with activated alleles in all tissues of the embryo proper. Crosses between epiblast-specific Cre lines and control PDGFRβ+/(S)Wt parents yielded the expected ratio of PDGFRβ+/Wt offspring that were all viable and fertile, indicating that knock-in expression of a wild-type cDNA at physiological levels does not produce a distinguishable phenotype. In further experiments, PDGFRβ+/+ mice were used as matched controls for their mutant littermates. Crosses between epiblast-specific Cre and PDGFRβ+/(S)J (or PDGFRβ+/(S)K) parents yielded mutant pups at the expected frequency before postnatal day 7 (P7) (βJ = 25/94, βK = 29/105). Mutant and control pups were indistinguishable from P0 until ~P6, but mutants were growth deficient during the second week and usually died by P14 (Figure 1A). We confirmed complete excision of the lox-stop-lox cassette by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) on tissue samples from Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K pups. To test the possibility that increased PDGFRβ signaling has additional consequences in the development of extra-embryonic organs, we used male germline-specific PrmCre (O'Gorman et al., 1997) to generate PDGFRβ+/K mice with increased PDGFRβ signaling in all embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues. This produced a postnatal phenotype that was indistinguishable from epiblast-specific Cre. From this survival data we conclude that increased PDGFRβ signaling by D849V (βK) or V536A (βJ) allows normal embryonic development, but produces postnatal phenotypes that we describe in detail below. In all subsequent studies we have not observed any consistent phenotypic difference between PDGFRβ+/J and PDGFRβ+/K mice or cell lines, and therefore all presented data is representative of either allele.

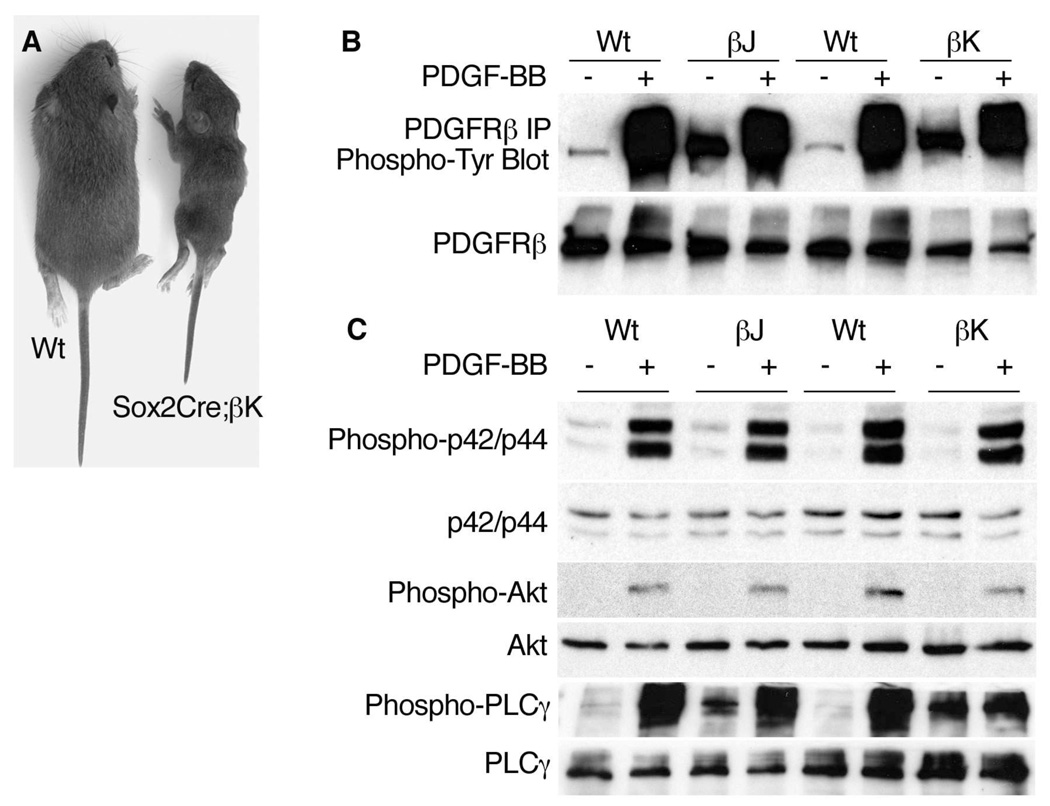

Figure 1. Constitutive and Inducible Signaling by PDGFRβ Mutant cDNA Knock-ins.

(A) Littermates at P14.

(B) Western blot analysis of protein expression and phosphorylation in PDGFRβ+/w (Wt), PDGFRβ+/J (βJ) and PDGFRβ+/K (βK) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Cells were serum starved, then harvested directly (−) or stimulated with 10ng/ml PDGF-BB (+) for 10 minutes. Protein lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (“IP”) with PDGFRβ antibody and were blotted for phosphotyrosine. On separate membranes, equal amounts of total protein were blotted for PDGFRβ.

(C) Western blot analysis of signaling protein expression and phosphorylation in PDGFRβ+/w (Wt), PDGFRβ+/J (βJ) and PDGFRβ+/K (βK) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Cells were serum starved, then harvested directly (−) or stimulated with 10ng/ml PDGF-BB (+).

See also Figure S1.

To examine the basal and ligand-inducible activity of mutant receptors, we cultured mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from control and mutant embryos. After 48 hr of serum starvation, PDGFRβ+/J and PDGFRβ+/K cells retained elevated phosphorylation of PDGFRβ compared to wild-type cells (Figure 1B). PDGFRβ from mutant cells was phosphorylated to higher levels after a pulse of PDGF-BB, similar to wild-type cells, indicating that PDGFRβ+/J and PDGFRβ+/K cells retain responsiveness to their cognate ligands. We also observed high basal phosphorylation of PLCγ1 in PDGFRβ+/J and PDGFRβ+/K cells, but p42/44 and Akt were significantly phosphorylated only with the addition of PDGF-BB (Figure S1C). Therefore, similar to the previously reported activation of PLCγ1 in PDGFRα+/J and PDGFRα+/K MEFs (Olson and Soriano, 2009), PDGFRβ J and PDGFRβK signaling has a specific effect on basal PLCγ1 phosphorylation.

Changes in Aortic Wall Architecture and Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotype with Increased PDGFRβ Signaling

In search of developmental defects that might contribute to the lethal phenotype of Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/Jand Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K pups, we observed thickening of the media in the ascending aorta during the second week (data not shown). To isolate this phenotype from consequences of PDGFRβ activation in other tissues, we generated mutant mice with Sm22Cre, which is active in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) of the aorta and adjacent mesenchymal tissues (Figure 2A,B) (Boucher et al., 2003) and in cardiomyocytes (data not shown). The excision efficiency of the lox-stop-lox cassette in Sm22Cre;PDGFRβ+/K aortas was 71% complete (by qRT-PCR). Activation of mutant PDGFRβ in VSMCs recapitulated the aorta phenotype seen with Sox2Cre mice, but otherwise the mutants were viable and fertile. Aortas from Sm22Cre;PDGFRβ+/K neonates were initially histologically normal (Figure 2C,D), but with age the media thickened, leading eventually to a 2-fold dilation of the vessel (Figure 2E,F). These alterations began in the ascending aorta during the second week and progressed through the arch and descending aorta to affect the entire thoracic and abdominal aorta by four weeks. Aortic dilation appears to reach homeostasis at this time without additional consequences, as we have never observed aortic rupture in Sm22Cre-derived mutants up to 1 year of age (n=10). Apoptotic cells (cleaved caspase-3+) were not detected in aortic sections from 6 month old Sm22Cre;PDGFRβ+/K mice (data not shown, embryonic trigeminal ganglion served as a positive control), suggesting that organ homeostasis is achieved by aortic VSMCs becoming refractory to PDGFRβ signaling rather than by increased apoptosis. It is likely that the in vivo configuration of vessel walls provides stabilizing cues to balance the proliferative potential of mutant mural cells.

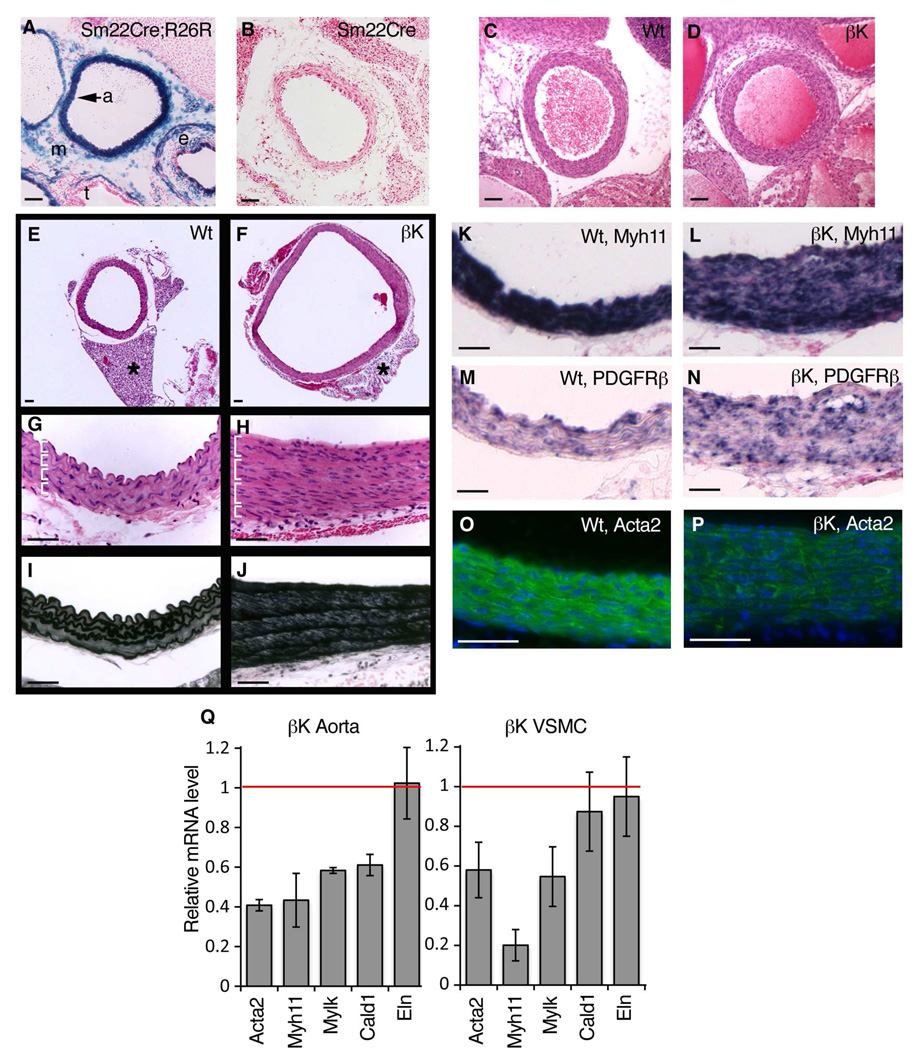

Figure 2. Altered Aortic Wall Architecture and Downregulation of Contractile Genes in Sm22Cre;PDGFRβ+/k Smooth Muscle Cells.

(A) Staining for β-gal activity (blue) in Sm22Cre;R26RlacZ aorta at E16.5. Activity is seen in aortic smooth muscle (a) as well as mosaic activity in periaortic mesenchyme (m), esophagus (e), and trachea (t).

(B) Negative control for β-gal activity in Sm22Cre mouse. There is no blue stain.

(C,D) Hematoxylin/eosin staining of ascending aorta in wild-type and Sm22Cre;PDGFRβ+/k littermates at P2.

(E,F) Low magnification images of descending aorta from P30 mice with 2-fold enlargement of the mutant lumen [F]. Asterisk marks anterior periaortic adipose that arises from an Sm22Cre-expressing lineage and is reduced to a rudiment in mutants (see also Figure S5). Images in [E,F] are the same magnification.

(G,H) Higher magnification of aortic wall in [E,F], stained with hematoxylin/eosin, with 2–4 smooth muscle cell nuclei per layer (marked with brackets) in mutant. Orientation: lumen is up.

(I,J) Aortic wall in [E,F], stained with Weigert’s elastic stain to visualize elastic lamellae.

(K–N) In situ hybridization for Myh11 and PDGFRβ mRNA (blue stain) in tunica media at P20. Myh11 is downregulated in mutant patches without detectable mRNA (visualized by pink counter stain in [L]). Same orientation as [G,H].

(O,P) Immunofluorescence for Acta2 (green) in tunica media at P20, with reduced protein expression in mutant. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI (blue).

(Q) qRT-PCR on RNA isolated from P20 aorta or cultured VSMCs, showing mutant mRNA levels compared to wild-type (red line), with decreased expression of contractile genes (Acta2, Myh11, Mylk, Cald1) but not tropoelastin (Eln) (mean +/− SD, n=3 aortas or independent cell lines per genotype).

See also Figure S2.

The tunica media is the largest part of the aortic wall and is composed of concentric musculoelastic layers. Each elastic lamella consists of a single layer of VSMCs and a layer of extracellular matrix, which is secreted by immature VSMCs during development and organized into fibers. Four to five intact elastic lamellae were easily identified in both control and mutant descending aortas (Figure 2G–J, brackets). Normally a single layer of VSMC nuclei separates each elastic lamella, but the most striking change in mutant aortas was increased cellularity, with two to four layers of nuclei between each mutant lamella (Figure 2G,H). VSMC proliferation was significantly increased in mutant aortas at E18.5, based on BrdU incorporation (Figure S2A–E), but BrdU incorporation was not increased in cardiomyocytes (data not shown).

The observed VSMC hyperplasia could be a response to cardiovascular challenges. To determine whether signals transduced by the mutant PDGFRβ can autonomously induce cell proliferation, we placed aortic rings in collagen gels and cultured them in serum free media for five days and scored cells that were released from the explant. Mutant aortas released >4-fold more VSMCs than controls, and this increase was due to proliferation because it could be blocked by mitomycin C (Figure S2F,G). As increased proliferation was seen over several days in vitro, as well as at E18.5 before any other alteration in aortic size or structure, we conclude that the mutant PDGFRβ autonomously induces VSMC proliferation.

VSMCs have the ability to alternate between quiescent/contractile and proliferative/non-contractile states depending on environmental cues (Owens et al., 2004). We hypothesized that since PDGFRβ signaling significantly increased proliferation, it might also down-regulate genes of the contractile apparatus, which would constitute further evidence of an alternate phenotypic state. Indeed, wild-type and mutant aorta sections expressed PDGFRβ and mutants contained medial areas negative for smooth muscle myosin mRNA (Myh11, also called SMMHC) (Figure 2K–N), a definitive marker of mature VSMCs (Owens et al., 2004). Expression of smooth muscle actin protein (Acta2, also called αSMA) was also broadly reduced (Figure 2O,P). Gene expression changes in aortic tissue were measured by qRT-PCR, which showed significantly reduced Myh11 (mutant level = 0.43 of control), smooth muscle actin (Acta2), smooth muscle myosin light-chain kinase (Mylk) and caldesmon, a calcium-binding regulator of smooth muscle contraction (Cald) (Figure 2Q). Elastin deficiency causes a hyperproliferative response in VSMCs (Li et al., 1998) but Eln mRNA was unchanged in our mutant aortas. Contractile genes were also expressed at reduced levels in cultured VSMCs, and Eln was again unchanged (Figure 2Q), indicating a cell-autonomous phenotype. We conclude that PDGFRβ signaling in aortic VSMCs induces a de-differentiation phenotype, resulting in thickening of the tunica media and an increase in aortic radius.

Changes in Pericyte Differentiation with Increased PDGFRβ Signaling

Increased PDGFRβ signaling in pericytes might be expected to influence angiogenesis and vascular remodeling in tissues that are sensitive to normal pericyte function, like the central nervous system and the retina. To test this hypothesis, we examined brain and retinal vasculature in Sox2Cre and Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K pups. While vessel density was somewhat reduced in P12 Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K brains compared to controls, the average capillary size was increased in mutant brains (Figure S3A–D). Mutant arteries and capillaries in flat mounted retinas at P7 were also enlarged (Figure S3E,F).

Individual pericytes extend processes to achieve appropriate coverage of arteries, capillaries and veins. Insufficient PDGFRβ signaling reduces pericyte coverage of CNS capillaries and results in poor blood-brain barrier (BBB) formation (Armulik et al., 2010; Daneman et al., 2010). To determine if increased PDGFRβ signaling alters pericyte coverage, we prepared flat mounted retinas from P7 mice and used double labeling for pericytes (NG2) and endothelial cells (FITS-GS-lectin) (Figure S3E). Pericyte coverage was increased on all types of mutant vessels as measured by NG2 area over FITC-GS-lectin (Figure S3E,G). We did not observe CNS or retina aneurisms nor did we observe fibrinogen or mouse IgG in the brain parenchyma (data not shown), and therefore the BBB appears to be intact in mice with increased PDGFRβ signaling, consistent with the high degree of pericyte coverage. Increased PDGFRβ signaling in pericytes increases vessel coverage in the retina and may also alter vessel diameter through unknown mechanisms.

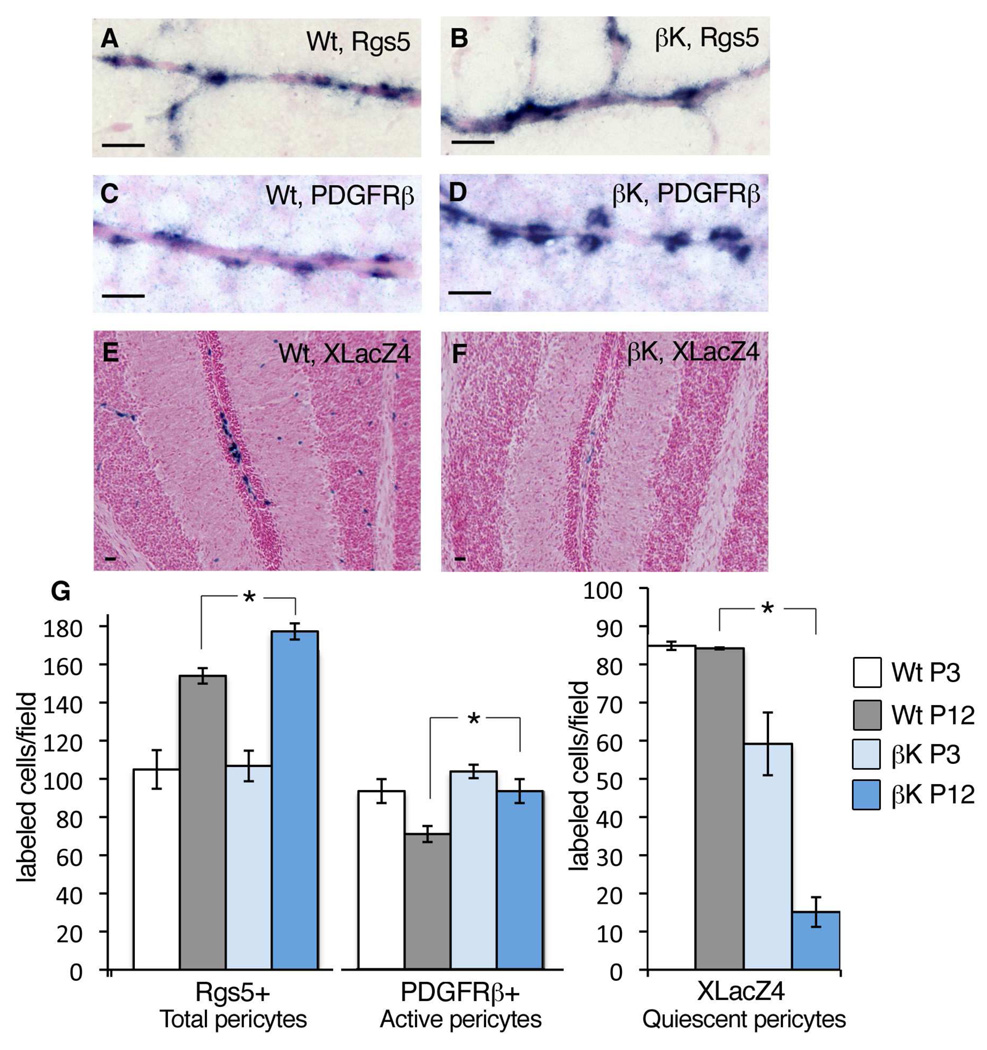

Increased PDGFRβ signaling might be expected to modulate pericyte differentiation similar to its observed ability to oppose aortic VSMC differentiation (Figure 2). A major challenge in studying pericytes is the lack of definitive markers or indicators of differentiation, but Rgs5 has emerged as a pericyte-specific marker in the brain (Bondjers et al., 2003). When comparing brains of wild-type and Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K pups at P3 and P12, we found that the number of Rgs5-expressing pericytes was similar between mutants and controls at P3. However, at P12 we counted somewhat higher numbers of Rgs5+ cells in Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K brains (Figure 3A,B,G). This is consistent with PDGFRβ as a positive regulator of pericyte progenitor proliferation/migration. In normal brains, PDGFRβ+ pericytes decreased in number over time, implying pericyte differentiation with downregulation of the gene. In mutant brains, however, the number of PDGFRβ+ pericytes was slightly higher than controls at P3 and higher still at P12 (Figure 3C,D,G), suggesting enrichment of activated or less differentiated pericytes in the population. To label quiescent or mature pericytes, we took advantage of the XlacZ4 promoter trap, which marks quiescent pericytes but is dynamically silenced in activated pericytes (Tidhar et al., 2001). Strikingly, increased PDGFRβ signaling coincided with fewer XlacZ4-expressing pericytes in mutant brains (Figure 3E,F,G). In summary, pericytes accumulate in higher numbers over time in mutant brains, based on Rgs5-expression. Furthermore, mutants have more pericytes in an active/progenitor state and fewer in a quiescent/differentiated state compared to controls. Similar changes in the number of PDGFRβ+ and XlacZ4+ cells were seen in other tissues from Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K mice, particularly in skeletal muscle and both brown and white adipose tissue (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that PDGFRβ signaling causes a shift in the differentiation status of pericytes.

Figure 3. Phenotypic Shift in Pericytes from Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K Brains.

(A–D) In situ hybridization for Rgs5 [A,B] or PDGFRβ mRNA [C,D] (blue stain) in brain pericytes at P3.

(E,F) Stain for β-gal activity (blue) expressed by the XLacZ4 promoter trap in quiescent pericytes of the cerebellum at P12.

(G) Quantification of CNS pericytes expressing Rgs5, PDGFRβ or XLacZ4 at P3 or P12. Total pericyte numbers increase over time (Rgs5+ cells). In mutant CNS, active pericytes (PDGFRβ+ cells) do not regress from P3 to P12, but conversely there are few quiescent pericytes (XLacZ4+ cells) (mean +/− SD, n=3 brain stems per genotype and time point).

See also Figure S3.

PDGFRβ-activated Pericytes Express Immune Response Signature Genes (IRSGs)

To identify targets of PDGFRβ signaling and potentially new markers for pericyte activation, we used microarray analysis to compare gene expression in control and mutant pericytes. We chose P1 as a time point when the number of Rgs5+ pericytes was similar between mutants and controls. This time is also before the appearance of an overt phenotype in the mutant brain vasculature, and by qRT-PCR we ensured that major markers for endothelial cells (Pecam, Vegfr2) were not significantly different (Figure 4A). We dissociated P1 mouse brains and isolated microvessel fragments with their associated pericytes by affinity to anti-PECAM-coated magnetic beads (Figure 4B). This method has been reported to recover pericytes (Bondjers et al., 2006) and we confirmed the efficiency of the method in parallel microvessel isolates from XLacZ4 transgenic mice (Figure 4C).

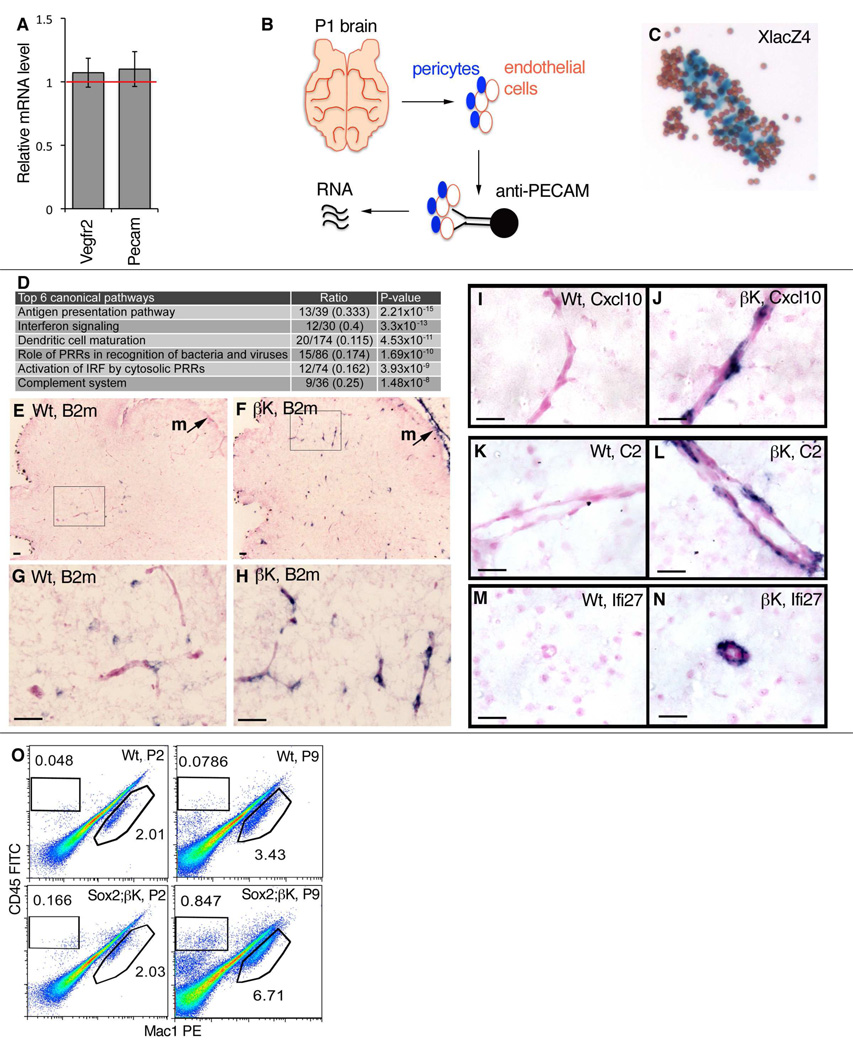

Figure 4. Microarray and In Situ Characterization of Immune Response Signature Genes (IRSGs) in Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ +/K Pericytes.

(A) qRT-PCR on RNA isolated from whole P1 brains, showing mutant mRNA levels relative to wild-type (red line), with normal expression of endothelial cell markers Vegfr2 and Pecam (mean +/− SD, n=3 brains per genotype).

(B) Work flow for isolation of RNA from brain microvessels with attached pericytes.

(C) XLacZ4-positive pericytes (blue) in isolated wild-type microvascular fragments after pull-down with attached Dynabeads (brown); a control experiment performed in parallel with tissue processed for microarrays.

(D) Differentially expressed pathways in brain microvessels at P1, identified by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Canonical pathways are defined by a cluster of related signature genes, which constitutes the ratio’s denominator. The ratio’s numerator is the number of signature genes that were changed in the microarray data. P-value is the probability that the ratio occurred by chance. IRF = interferon regulator factor; PRR = pattern recognition receptor. Further information is available in Table S1 and supplemental.database.

(E–H) ISH for B2m (blue stain) in cerebellum and meninges (m) at P2.

(I–N) ISH for IRSGs Cxcl10, C2, and Ifi27 (blue stain) in mutant pericytes at P12 [I–L] or P7 [M,N].

(O) Representative FACS analysis of leukocytes in the brain of control and mutants at P2 and P9. Significant increase in gated CD45+Mac1− and CD45+Mac1+ populations are seen in Sox2Cre/PDGFRβ +/K mutants at P9. Numerical data for each gate is the percentage of total cells analyzed.

See also Figure S4 and Table S1.

RNA was isolated from four control (wild-type or Sox2Cre) and four mutant (Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K) brains, and used to prepare labeled samples for microarray hybridization. From this analysis, 550 transcripts exhibited >1.5 fold change with a p value < 0.05. Unexpectedly, genes commonly used as pericyte markers were not scored as significantly changed, including Rgs5 and Cspg4, suggesting that they may not be targets of PDGFRβ signaling. Instead, most of the changes were in genes not previously associated with pericytes. Modeling of these data with two different pathway-mining software packages revealed significant upregulation of transcripts involved in immune functions (Figure 4D and Table S1). We selected immune response signaling genes (IRSGs) from these categories for validation in situ, to see if they were overexpressed in pericytes. We examined expression of β2-microglobulin (B2m) a highly induced chemokine (Cxcl10) a representative interferon regulated gene (Ifi27) and a complement component (C2). Each of these mRNA transcripts, as well as protein in the case of β2M, was higher in mutant brain pericytes and meningeal cells (Figure 4E–N, and data not shown). We tested alternative possibilities that endothelial cells or leukocytes could be the source of overexpressed IRSGs, but results for these cell types were negative (Figure S4A,B). However, cultured mutant microvascular fragments containing pericytes continued to overexpress IRSGs (Figure S4C), and PDGF-BB could induce IRSGs in wild type microvascular fragments in low serum conditions (Figure S4C). As additional supporting evidence that IRSG expression is autonomous to pericytes/mesenchymal progenitor cells, we found overexpression of IRSGs in cultured subcutaneous mesenchymal cells even after several passages (see below and Figure S7D). Taken together, these data show that pericyte plasticity includes the potential to activate a battery of genes involved in innate and adaptive immunity, and PDGFRβ activity can modulate this response.

The PDGFRβ-induced immune response signature could modulate inflammatory properties of endothelial cells, leading to increased leukocyte adhesion and transmigration. Furthermore, many of the IRSGs are chemokines involved in leukocyte trafficking (Cxcl10, Cxcl9, Cxcl12, Ccl5, Ccl2, see Table S1). We used fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) to examine bone marrow-derived cells in the brain at P2 and P9. In P2 brains, we found no significant difference between control and Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K brains in the number of CD45+ cells (all leukocytes) and CD45+Mac1+ double positive cells (macrophages, microglia and some other cells of the innate immune system). However, at P9 the number of CD45+ and CD45+Mac1+ cells in the brain was significantly increased in Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K pups (Figure 4O). The potential for pericytes to influence transmigration of leukocytes through vessel walls has been previously addressed in tumors (Hamzah et al., 2008). Our findings suggest that pericytes have the potential to activate a battery of immune response genes that initiate immune cell recruitment in the brain and possibly other tissues. Pericyte-mediated inflammatory responses could be an important component of autoimmune diseases, and may contribute to the observed lethality in Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K pups.

PDGFRβ Signaling Blocks White Adipose Differentiation

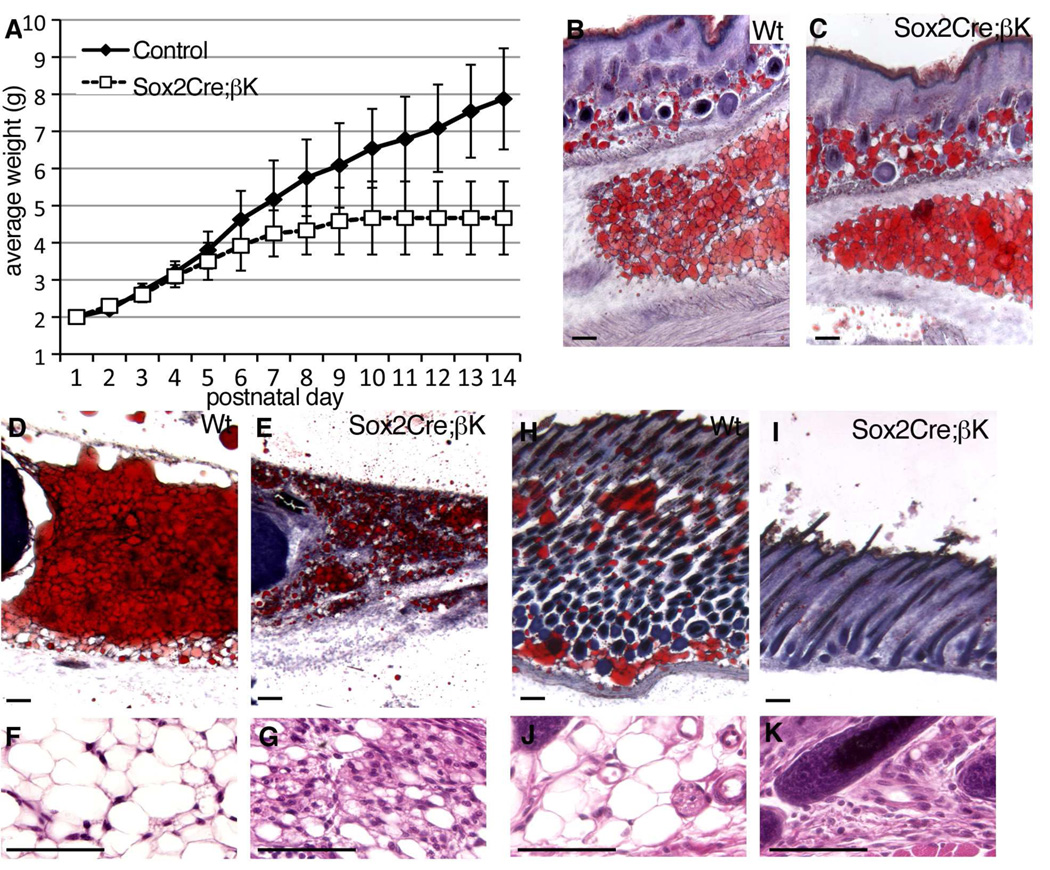

All PDGFRβ+/J and PDGFRβ+/K pups generated with epiblast-specific Cre (Sox2Cre, Meox2Cre) and male germline Cre (PrmCre) entered growth stasis after the first week (Figure 5A, data not shown). Mutant pups nursed and their stomachs contained milk. We could not find any defects in gastrointestinal vascular or lacteal development that could explain the observed growth stasis. This phenotype was not seen in smooth muscle-specific (Sm22Cre) or endothelial and blood cell-specific (Tie2Cre) mutants.

Figure 5. Inhibition of White Fat in vivo.

(A) Weight plot of control (combined wild-type, Sox2Cre, and PDGFRβ +/(S)K, n=24) versus Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ +/K (n=10) pups during the second postnatal week (mean +/− SD).

(B,C) Histological sections of flank skin with nascent subcutaneous WAT and inguinal WAT from littermates at P3, stained with oil Red O (ORO) to detect lipids (red).

(D,E) Inguinal WAT at P13 stained with ORO.

(F,G) Inguinal WAT at P13 stained with hematoxylin/eosin.

(H,I) Flank skin and subcutaneous WAT at P13 stained with ORO. WAT is virtually eliminated from mutant skin.

(J,K) Subcutis at P13 stained with hematoxylin/eosin.

See also Figure S5.

Mice are born with brown adipose tissue (BAT) but white adipose tissue (WAT) only develops postnatally. PDGFRβCre has been used to lineage trace white adipocytes in development and to provide evidence that mural cells are white adipocyte progenitors (Tang et al., 2008). We therefore monitored adipogenesis in our mice before growth stasis (P3) and after its onset (P11 – P14). Nascent subcutaneous and inguinal WAT developed in controls and mutants by P3 (Figure 5B,C). At P13, mutant inguinal and subcutaneous WAT contained reduced lipids but a higher cell density (Figure 5D–K). At this time, only rudimentary mesenteric adipose depots could be detected in mutants (Figure S5A,B). In addition to these changes in juvenile Sox2 mutants, lineage tracing showed that Sm22Cre is active in mesenchymal cells (Figure 2A) that give rise to periaortic adipose (Figure S5C). Closer examination of adult Sm22Cre;PDGFRβ+/K mice revealed isolated reduction of periaortic adipose (Figure S5D,E). Therefore, despite initial differentiation of some adipocytes, WAT failed to fully develop in mice with increased PDGFRβ signaling in pericytes and other mesenchymal cells. Interscapular BAT was present in newborn controls and mutants (Figure S5F,G), and was not significantly reduced in P13 pups (data not shown).

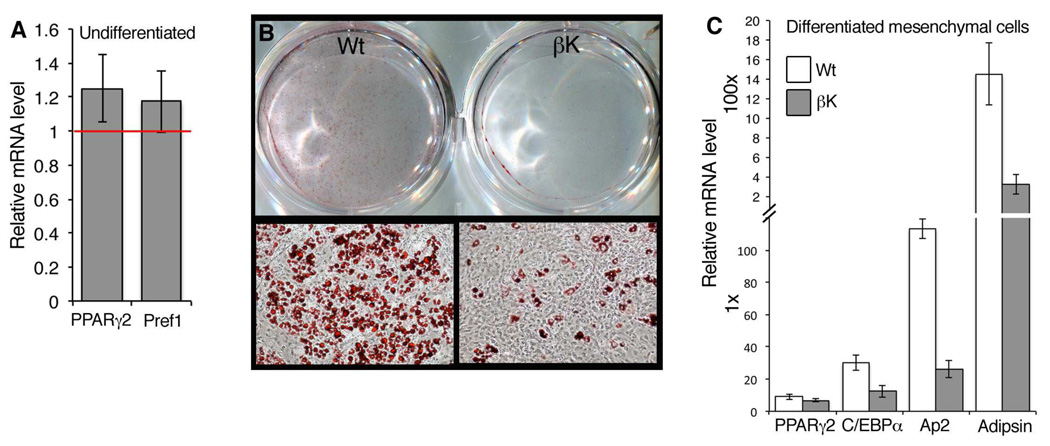

To isolate the effect on adipogenesis from additional phenotypes that may result from PDGFRβ activation, we established cultures of subcutaneous mesenchymal cells (ScMCs) from newborn (P1) pups and assayed their capacity for adipogenesis in vitro. These primary cells spontaneously differentiate into adipocytes at low efficiency without differentiation media (data not shown). Before inducing differentiation, we tested control and Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K cells for expression of PPARγ2, a key transcriptional regulator of adipogenesis, and Pref-1, a marker for mesenchymal cells and preadipocytes. These genes were modestly increased in mutant ScMCs but the difference was not significant (Figure 6A). Control ScMCs treated with differentiation media were highly adipogenic after 12 days of differentiation as assessed by Oil Red O staining, but Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K cells differentiated very poorly (Figure 6B). We did not see evidence of ScMC differentiation towards brown fat (Figure S6). Control ScMC differentiation corresponded to induction of adipogenic transcription factors (PPARγ2 and C/EBPα) and differentiation markers (Ap2 and Adipsin). Consistent with severely reduced lipid accumulation in mutant ScMCs, C/EBPα, Ap2 and Adipsin were induced at lower levels in mutant cells (Figure 6C). Taken together, these results in isolated cells show that increased PDGFRβ signaling in preadipocytes, which may be pericytes or other mesenchymal cells, is inhibitory to white adipocyte differentiation.

Figure 6. Inhibition of White Adipocyte Differentiation in vitro.

(A) qRT-PCR on RNA isolated from undifferentiated SuMCs, showing Sox2Cre/PDGFRβ+/K mRNA levels compared to controls (red line). Preadipocyte markers PPARγ2 and Pref-1 are slightly increased in mutant cells (mean +/− SD, n=3 independent cultures per genotype).

(B) Oil Red O stain performed on control and mutant SuMCs after 12 days of differentiation.

(C) qRT-PCR on RNA isolated from differentiated SuMCs, expressed as fold-increase in mRNA levels over basal level in undifferentiated SuMCs. WAT markers C/EBPα, AP2, and Adipsin are inhibited in mutant cells (mean +/− SD, n=3 independent cultures per genotype).

See also Figure S6.

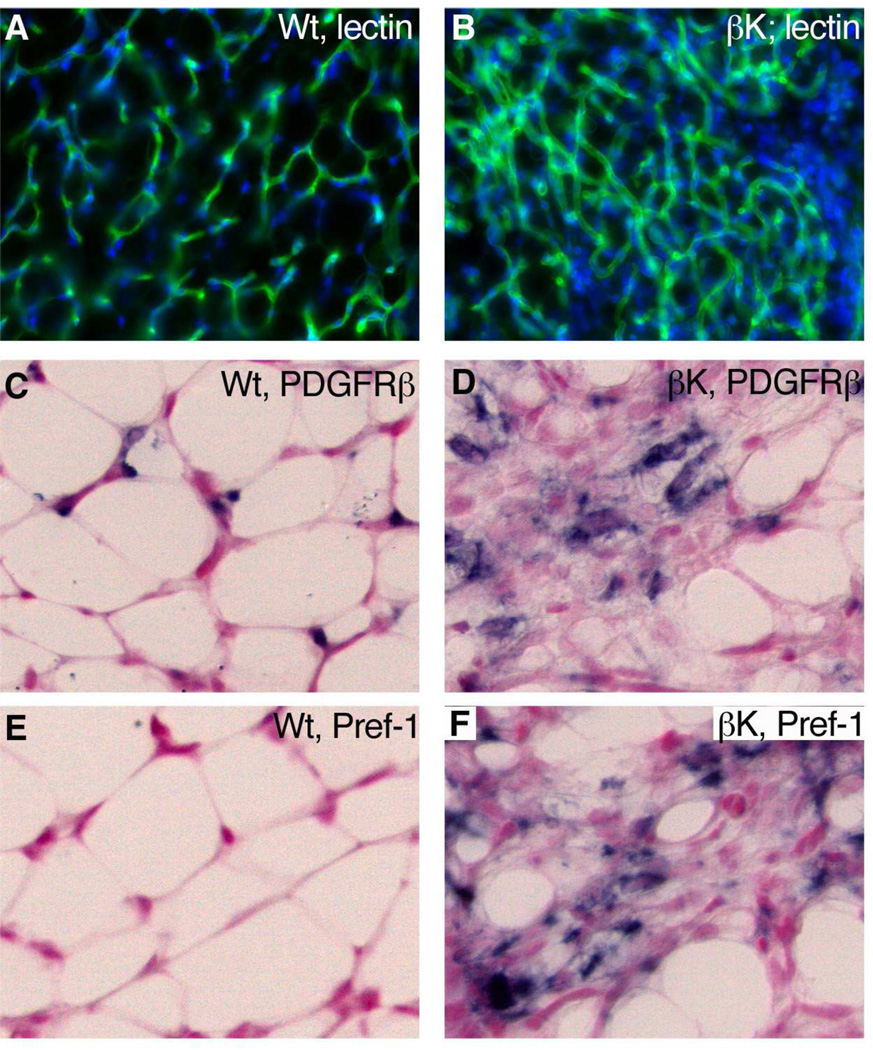

Mutant White Adipose is Composed of Adipocyte Progenitors and Leukocytes

To uncover developmental mechanisms for the loss of adipose, we examined P13 WAT for apoptotic cells, vascular regression, and evidence of preadipocyte accumulation. Few apoptotic cells were detected in wild-type or Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K adipose by immunostaining for cleaved caspase-3 (data not shown), suggesting that the loss of adipose is not due to cell death. Reduced blood supply could oppose adipogenesis because angiogenesis and adipogenesis are developmentally and functionally linked (Cao, 2007; Rupnick et al., 2002). However, staining with FITC-GS-lectin revealed a dense network of capillaries in WAT of Sox2Cre;PDGFRβ+/K pups (Figure 7A,B). Finally, we used expression of PDGFRβ and Pref-1 to test for pericyte/preadipocyte accumulation within mutant WAT. Normal WAT at P13 contained few PDGFRβ-expressing cells and fewer still Pref-1-expressing preadipocytes, but mutant adipose held abundant PDGFRβ+ and Pref-1+ cells (Figure 7C–F). Pref-1 is a marker for preadipocytes that is downregulated during differentiation (Smas and Sul, 1993). Pref-1, also known as Dlk1, is also a novel marker reported in embryonic brain pericyte progenitors (Bondjers et al., 2006). Although forced expression of a soluble form of Pref-1 can impair adipogenesis in mice (Lee et al., 2003), we observed normal downregulation of Pref-1 in nascent WAT at P3 in both controls and mutants. (Figure S7A–C) and Pref-1 was only re-expressed in mutant WAT at P13 (Figure 7F). This is consistent with Pref-1 being a pericyte or preadipocyte marker rather than being a functional part of our system.

Figure 7. Progenitor Cells in Mutant WAT.

(A,B) Immunofluorescence for capillary endothelium of inguinal WAT at P13, stained with FITC-GS-lectin.

(C–F) ISH for PDGFRβ or Pref-1 (blue stain) in inguinal adipose at P13. An increase in these markers indicates the accumulation of pericytes/preadipocytes in mutant adipose.

See also Figure S7.

As shown by our in vitro analysis of isolated ScMCs, PDGFRβ plays an intrinsic role in opposing adipocyte differentiation (Figure 6B,C). We also tested the expression of IRSGs Cxcl10, C2, and Ifi27 in the same cell cultures before inducing adipogenesis, and found IRSGs to be overexpressed in mutant cells compared to control cells (Figure S7D). The IRSGs were also overexpressed in nascent WAT of mutant pups at P3 (Figure S7E–J). Normal WAT is rich in leukocytes and macrophages. To see if additional immune cells were recruited to mutant WAT in vivo, we performed FACS of the stromal vascular fraction of control and mutant inguinal WAT at P9. The total number of cells in the mutant stromal vascular fraction was increased 1.5-fold compared to control WAT (data not shown). The proportion of CD45+Mac1+ double positive cells was increased 1.44-fold in mutants (Wt CD45+Mac1+ = 13.30 +/− 3.4%, βK CD45+Mac1+ = 19.95 +/−3.05%, n=3) and the proportion of CD45+Mac1− leukocytes was 3.59-fold higher (Wt CD45+Mac1− = 13.83 +/− 3.4%, βK CD45+Mac1− = 47.8 +/− 14.25%, n=3). Therefore, PDGFRβ signaling alters the ground state of adipocyte progenitor cells, which inhibits WAT differentiation. Concomitantly, increased PDGFRβ activity induces IRSGs that lead to recruitment of significant numbers of bone marrow-derived cells to the hypotrophic WAT. Consistent with evidence that PDGFRβ+ mural cells are adipocyte progenitors in the newborn mouse (Tang et al., 2008), our findings demonstrate that PDGFRβ activity regulates the balance between progenitor and differentiated states of mural cells in multiple tissues.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that PDGFRβ signaling opposes differentiation of vascular smooth muscle and pericytes, inhibits the differentiation of white adipocyte progenitors derived from pericytes or other mesenchymal cells, and maintains progenitor potential in vivo. Inhibition of adipogenesis was the most striking consequence of retained progenitor potential due to PDGFRβ signaling, as WAT became enriched for PDGFRβ+ and Pref-1+ cells. PDGFRβ signaling also promoted an immature phenotype in VSMCs and CNS pericytes. Thus, PDGFRβ provides important regulatory cues to oppose differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells. Engagement of this pathway may be highly relevant in the development of mesenchymal stem cells towards therapeutic ends.

Increasing PDGFRβ signaling specifically in VSMCs induced key aspects of a “phenotypic switch” (Owens et al., 2004), including down-regulation of contractile apparatus genes and increased proliferation, but the mice remained healthy into adulthood without spontaneous atherosclerosis or neointima formation. Yet PDGF expression has been reported in many types of vascular and inflammatory cells and PDGFRβ signaling clearly has a role in experimentally induced cardiovascular disease (Raines, 2004) and cardiac challenge (Chintalgattu et al., 2010). It is likely that in the context of an intact vessel wall, properly integrated VSMCs become refractory to PDGF signaling. Environmental conditions that disrupt matrix contacts would be expected to synergize with PDGF signaling, resulting in VSMC activation and cardiovascular disease.

Pericytes converge on newly formed capillaries and produce extracellular matrix to induce quiescent, leak resistant, optimally functional vessels (Carmeliet, 2003; Jain, 2003). Endothelial cells and pericytes exchange signals such as PDGF-B/PDGFRβ to regulate this process (Armulik et al., 2005). When pericytes fail to adequately coat capillaries in mice with deficient PDGF-B/PDGFRβ signaling, the vascular consequences include leaky vessels and loss of blood-brain barrier (Armulik et al., 2010; Daneman et al., 2010; Hellstrom et al., 2001; Lindahl et al., 1997). We show that increased PDGFRβ signaling leads to increased pericyte coverage of blood vessels and induced changes in pericyte differentiation. There have been few attempts to define pericyte “activation” in molecular terms (Berger et al., 2005). Our microarray profiling and subsequent characterization revealed that a major outcome of PDGFRβ signaling in pericytes and other mesenchymal progenitors is the activation of a latent immunological potential. This resulted in recruitment of large numbers of leukocytes to the brain. Loss of Rgs5 has been shown to alter pericyte differentiation in tumors, and leads to recruitment of immune cells that improve cancer outcomes (Hamzah et al., 2008). Our finding that altered pericyte differentiation can lead to immune cell recruitment in the developing brain suggests the potential for pericytes to play a role in CNS inflammation or in autoimmune disease, and this merits further testing. It remains to be seen whether these aspects of pericyte activation are helpful or harmful in the adult CNS, and it will be important to understand the previously unappreciated potential of PDGF to modulate this phenotype.

Many adipocyte progenitors are perivascular cells, but clearly not all pericytes adopt an adipogenic fate in the organism (Rodeheffer et al., 2008; Tang et al., 2008; Zeve et al., 2009). There is also evidence for adipocyte progenitors that differ from pericytes (Joe et al., 2010; Majka et al., 2010; Uezumi et al., 2010). Fat development in vivo is still a poorly understood process. In our mouse model, WAT initially appears normal at P3 but is defective thereafter. This leads us to postulate that WAT arises from more than one developmental lineage with PDGFRβ having a negative impact during a second wave of adipogenesis. Our work clearly shows that PDGFRβ signaling inhibits WAT differentiation in vitro, acting in adipocyte progenitors that may be pericytes or anatomically distinct mesenchymal cells. The anti-adipogenic effect of PDGFRβ signaling could not have been predicted from previous developmental studies because PDGFB/PDGFRβ-deficient mice die before the stage at which most adipogenesis occurs (Leveen et al., 1994; Soriano, 1994). Some of the molecular steps in fat differentiation, that also support a role for PDGF in inhibiting adipogenesis, have been described in tissue culture. In the 3T3-L1 preadipocyte cell line, down-regulation of PDGFRβ is one of the first events following treatment with differentiation medium, occurring at just 6 hours (Vaziri and Faller, 1996), while induction of PPARγ and C/EBPα are first detectable after 2–3 days, and adipocyte morphology is reached 4–5 days later. Conversely, addition of PDGF-BB to the differentiation media partially inhibits lipid accumulation and induction of C/EBPα, PPARγ2, aP2 and adiponectin in 3T3-L1 cells (Artemenko et al., 2005).

Our findings raise the possibility that agonists or antagonists to PDGFRs might be useful agents for controlling adipogenesis. Components of the immune response battery (IRSGs) may also be candidates for mediating the inhibitory effect on white adipocyte differentiation. However, we have also shown that chronic activation of PDGFRα can lead to multiorgan fibrosis (Olson and Soriano, 2009), and PDGF is a potent mitogen that can promote tumor formation (Andrae et al., 2008; Pietras et al., 2003). Focusing on signaling events engaged downstream of the PDGF receptors may therefore provide more specificity in potential treatments. A better understanding of how PDGFRβ regulates pericyte or mesenchymal progenitor status and immune responses could thus lead to the identification of novel therapeutic targets for cardiovascular and obesity-related diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

A detailed description of ES cell targeting and vector design is provided in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. All procedures described in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Mount Sinai and the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. Embryos and pups were examined in mixed C57BL6/129S4 backgrounds, and mutants generated with Meox2Cre were also examined in a co-isogenic 129S4 background, with identical phenotypes. All analyses were based on a minimum of three mutants and littermate controls (wild-type or Cre-only).

Brain Microvessel Purification

Microvessels were purified as described (Bondjers et al., 2006). For each brain, 10µl rat anti-Pecam antibody (BD Pharmingen) was bound to 50µl anti-rat Dynabeads (Invitrogen 110.35) by overnight incubation, followed by washing with PBS + 0.1% BSA + 2mM EDTA. The next day, P1 pups were sacrificed and each brain was minced and triturated in 4ml 1xHBSS (+Ca/Mg) + 1% BSA + 5mg/ml collagenase type 1 (Gibco 17100-017). After 15 minutes at 37°C with gentle rocking, cells and microvascular fragments were filtered through 100µm nylon mesh, and rinsed twice with ice-cold wash buffer (PBS/BSA/EDTA). Cell slurry was then incubated with anti-Pecam Dynabeads for 30 minutes at 4°C with end-over-end rotation. Beads and attached microvessels were recovered with a magnet and washed 5x with ice-cold wash buffer, followed by RNA isolation. Microarray analysis is described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Flow Cytometery

For FACS analysis, brains and inguinal WAT were excised and single cells isolated by digestion with 0.4% collagenase in DMEM + 1.5%BSA for 1 hour at 37°C. After filtering through a 40µm filter, cells were resuspended in HBSS + 2% FBS and anti-Fc binding was blocked for 15 minutes with anti-CD16 (eBioscience) at 4°C. Next, cells were labeled with anti-Mac1 (CD11b-PE) (eBioscience) and anti-CD45.2-FITC (BD Pharmingen) for 15 minutes. Compensation was set using single-labeled samples, and samples were sorted on a FACSCalibur cytometer and data was analyzed with FlowJo software. For flow cytometry, single cells were filtered from bone marrow, spleen, and thymus, and resuspended in HBSS + 2% FBS. After blocking, cells were labeled with anti-CD45.2-FITC and 2×106 CD45+ cells were sorted on a MoFlo cell sorter.

Subcutaneous Mesenchymal Cell Isolation and Differentiation

Subcutaneous mesenchymal cells (SuMCs) were isolated as described (Lichti et al., 2008). Briefly, P0–P1 pups were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation and washed in 70% ethanol. Whole skins were removed and floated dermis-down on cold 0.25% trypsin (without EDTA) overnight at 4°C. Epidermis was then removed, subcutaneous tissue was digested with 0.4mg/mL collagenase in DMEM + 1.5% BSA for 1 hour at 37°C, and released cells were filtered through a 100µm filter. Hair follicle buds were removed by centrifugation at 15g. SuMCs were then plated at a density of 1 mouse/10cm dish, and grown in DMEM + 10% FBS supplemented with antibiotics. 24–48 hrs later, each culture was expanded onto a 15cm dish and grown to confluence. For differentiation assays, passage 2 cells were plated at 5×105 cells/6 well dish. Upon reaching confluence, undifferentiated SMCs were either harvested for RNA analysis, or induced to differentiate. Adipogenesis was induced by two cycles of induction/maintenance medium, consisting of 48 hours in induction medium (DMEM + 10% FBS, 10µg/ml insulin, 0.25µg/ml dexamethasone, 0.5mM IBMX), or 48 hours in maintenance medium (DMEM + 10% FBS, 10µg/ml insulin). After two cycles (8 days), cells were held for an additional 4 days in maintenance medium. For staining, cells were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 10 minutes, then rinsed in PBS, H2O, and 60% isopropanol sequentially. Staining was performed with oil red O (0.3% oil red O in 60% isopropanol) for 30 minutes, followed by rinse with 60% isopropanol and H2O, sequentially.

HIGHLIGHTS.

PDGF signaling in aortic mesenchyme opposes vascular smooth muscle differentiation.

Brain pericytes acquire an immune response phenotype when activated by PDGFRβ.

PDGF signaling inhibits the differentiation of white adipocytes in vivo and in vitro.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Amelie Cornil and G. Michael Upchurch for expert technical assistance; Rob Krauss, Sergio Lira, Paul Kincade and our laboratory colleagues for stimulating discussions and critical comments on the manuscript; Tearina Chu and the Mount Sinai Microarray-PCR-Bioinformatics shared resource for microarray hybridization; Yezhou Sun of the Mount Sinai Bioinformatics Laboratory for bioinformatics and statistics; and Taishan Hu and Jacob Bass for assistance with cell cytometry. L.E.O. was supported by the American Cancer Society and the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. This work was also supported by grants RO1HD24875 and R37HD25326 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to P.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Data include one table, seven figures and Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

REFERENCES

- Andrae J, Gallini R, Betsholtz C. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1276–1312. doi: 10.1101/gad.1653708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res. 2005;97:512–523. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000182903.16652.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A, Genove G, Mae M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, He L, Norlin J, Lindblom P, Strittmatter K, et al. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature. 2010;468:557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature09522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artemenko Y, Gagnon A, Aubin D, Sorisky A. Anti-adipogenic effect of PDGF is reversed by PKC inhibition. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:646–653. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M, Bergers G, Arnold B, Hammerling GJ, Ganss R. Regulator of G-protein signaling-5 induction in pericytes coincides with active vessel remodeling during neovascularization. Blood. 2005;105:1094–1101. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnegard M, Enge M, Norlin J, Gustafsdottir S, Fredriksson S, Abramsson A, Takemoto M, Gustafsson E, Fassler R, Betsholtz C. Endothelium-specific ablation of PDGFB leads to pericyte loss and glomerular, cardiac and placental abnormalities. Development. 2004;131:1847–1857. doi: 10.1242/dev.01080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondjers C, He L, Takemoto M, Norlin J, Asker N, Hellstrom M, Lindahl P, Betsholtz C. Microarray analysis of blood microvessels from PDGF-B and PDGF-Rbeta mutant mice identifies novel markers for brain pericytes. FASEB J. 2006;20:1703–1705. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4944fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondjers C, Kalen M, Hellstrom M, Scheidl SJ, Abramsson A, Renner O, Lindahl P, Cho H, Kehrl J, Betsholtz C. Transcription profiling of platelet-derived growth factor-B-deficient mouse embryos identifies RGS5 as a novel marker for pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:721–729. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63868-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher P, Gotthardt M, Li WP, Anderson RG, Herz J. LRP: role in vascular wall integrity and protection from atherosclerosis. Science. 2003;300:329–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1082095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y. Angiogenesis modulates adipogenesis and obesity. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2362–2368. doi: 10.1172/JCI32239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat Med. 2003;9:653–660. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara F, Goumans MJ, Forsberg H, Ahgren A, Rasola A, Aspenstrom P, Wernstedt C, Hellberg C, Heldin CH, Heuchel R. A gain of function mutation in the activation loop of platelet-derived growth factor beta-receptor deregulates its kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42516–42527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintalgattu V, Ai D, Langley RR, Zhang J, Bankson JA, Shih TL, Reddy AK, Coombes KR, Daher IN, Pati S, et al. Cardiomyocyte PDGFR-beta signaling is an essential component of the mouse cardiac response to load-induced stress. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:472–484. doi: 10.1172/JCI39434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, Chen CW, Corselli M, Park TS, Andriolo G, Sun B, Zheng B, Zhang L, et al. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby JR, Seifert RA, Soriano P, Bowen-Pope DF. Chimaeric analysis reveals role of Pdgf receptors in all muscle lineages. Nat Genet. 1998;18:385–388. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Meirelles L, Caplan AI, Nardi NB. In search of the in vivo identity of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2287–2299. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman R, Zhou L, Kebede AA, Barres BA. Pericytes are required for blood-brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis. Nature. 2010;468:562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature09513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamzah J, Jugold M, Kiessling F, Rigby P, Manzur M, Marti HH, Rabie T, Kaden S, Grone HJ, Hammerling GJ, et al. Vascular normalization in Rgs5-deficient tumours promotes immune destruction. Nature. 2008;453:410–414. doi: 10.1038/nature06868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Lewis P, Pevny L, McMahon AP. Efficient gene modulation in mouse epiblast using a Sox2Cre transgenic mouse strain. Mech Dev. 2002;119 Suppl 1:S97–S101. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Duensing A, McGreevey L, Chen CJ, Joseph N, Singer S, Griffith DJ, Haley A, Town A, et al. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 2003;299:708–710. doi: 10.1126/science.1079666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH, Westermark B. Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1283–1316. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom M, Gerhardt H, Kalen M, Li X, Eriksson U, Wolburg H, Betsholtz C. Lack of pericytes leads to endothelial hyperplasia and abnormal vascular morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:543–553. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom M, Kalen M, Lindahl P, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Role of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development. 1999;126:3047–3055. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard SR. Juxtamembrane autoinhibition in receptor tyrosine kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:464–471. doi: 10.1038/nrm1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irusta PM, DiMaio D. A single amino acid substitution in a WW-like domain of diverse members of the PDGF receptor subfamily of tyrosine kinases causes constitutive receptor activation. EMBO J. 1998;17:6912–6923. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RK. Molecular regulation of vessel maturation. Nat Med. 2003;9:685–693. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe AW, Yi L, Natarajan A, Le Grand F, So L, Wang J, Rudnicki MA, Rossi FM. Muscle injury activates resident fibro/adipogenic progenitors that facilitate myogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:153–163. doi: 10.1038/ncb2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Villena JA, Moon YS, Kim KH, Lee S, Kang C, Sul HS. Inhibition of adipogenesis and development of glucose intolerance by soluble preadipocyte factor-1 (Pref-1) J Clin Invest. 2003;111:453–461. doi: 10.1172/JCI15924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leveen P, Pekny M, Gebre-Medhin S, Swolin B, Larsson E, Betsholtz C. Mice deficient for PDGF B show renal, cardiovascular, and hematological abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1875–1887. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DY, Brooke B, Davis EC, Mecham RP, Sorensen LK, Boak BB, Eichwald E, Keating MT. Elastin is an essential determinant of arterial morphogenesis. Nature. 1998;393:276–280. doi: 10.1038/30522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichti U, Anders J, Yuspa SH. Isolation and short-term culture of primary keratinocytes, hair follicle populations and dermal cells from newborn mice and keratinocytes from adult mice for in vitro analysis and for grafting to immunodeficient mice. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:799–810. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl P, Hellstrom M, Kalen M, Karlsson L, Pekny M, Pekna M, Soriano P, Betsholtz C. Paracrine PDGF-B/PDGF-Rbeta signaling controls mesangial cell development in kidney glomeruli. Development. 1998;125:3313–3322. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.17.3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl P, Johansson BR, Leveen P, Betsholtz C. Pericyte loss and microaneurysm formation in PDGF-B-deficient mice. Science. 1997;277:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson PU, Looman C, Ahgren A, Wu Y, Claesson-Welsh L, Heuchel RL. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta constitutive activity promotes angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2142–2149. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000282198.60701.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majka SM, Fox KE, Psilas JC, Helm KM, Childs CR, Acosta AS, Janssen RC, Friedman JE, Woessner BT, Shade TR, et al. De novo generation of white adipocytes from the myeloid lineage via mesenchymal intermediates is age, adipose depot, and gender specific. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14781–14786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003512107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Gorman S, Dagenais NA, Qian M, Marchuk Y. Protamine-Cre recombinase transgenes efficiently recombine target sequences in the male germ line of mice, but not in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14602–14607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson LE, Soriano P. Increased PDGFRalpha activation disrupts connective tissue development and drives systemic fibrosis. Dev Cell. 2009;16:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietras K, Sjoblom T, Rubin K, Heldin CH, Ostman A. PDGF receptors as cancer drug targets. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:439–443. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raines EW. PDGF and cardiovascular disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:237–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodeheffer MS, Birsoy K, Friedman JM. Identification of white adipocyte progenitor cells in vivo. Cell. 2008;135:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupnick MA, Panigrahy D, Zhang CY, Dallabrida SM, Lowell BB, Langer R, Folkman MJ. Adipose tissue mass can be regulated through the vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10730–10735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162349799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smas CM, Sul HS. Pref-1, a protein containing EGF-like repeats, inhibits adipocyte differentiation. Cell. 1993;73:725–734. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90252-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Abnormal kidney development and hematological disorders in PDGF beta-receptor mutant mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1888–1896. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallquist MD, French WJ, Soriano P. Additive effects of PDGF receptor beta signaling pathways in vascular smooth muscle cell development. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E52. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallquist MD, Klinghoffer RA, Heuchel R, Mueting-Nelsen PF, Corrin PD, Heldin CH, Johnson RJ, Soriano P. Retention of PDGFR-beta function in mice in the absence of phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase and phospholipase Cgamma signaling pathways. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3179–3190. doi: 10.1101/gad.844700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallquist MD, Soriano P. Epiblast-restricted Cre expression in MORE mice: a tool to distinguish embryonic vs. extra-embryonic gene function. Genesis. 2000;26:113–115. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<113::aid-gene3>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Zeve D, Suh JM, Bosnakovski D, Kyba M, Hammer RE, Tallquist MD, Graff JM. White fat progenitor cells reside in the adipose vasculature. Science. 2008;322:583–586. doi: 10.1126/science.1156232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidhar A, Reichenstein M, Cohen D, Faerman A, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Shani M. A novel transgenic marker for migrating limb muscle precursors and for vascular smooth muscle cells. Dev Dyn. 2001;220:60–73. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1089>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uezumi A, Fukada S, Yamamoto N, Takeda S, Tsuchida K. Mesenchymal progenitors distinct from satellite cells contribute to ectopic fat cell formation in skeletal muscle. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:143–152. doi: 10.1038/ncb2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri C, Faller DV. Down-regulation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor expression during terminal differentiation of 3T3-L1 pre-adipocyte fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13642–13648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeve D, Tang W, Graff J. Fighting fat with fat: the expanding field of adipose stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:472–481. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.