Abstract

We report the development of ruthenium-based metathesis catalysts with chelating N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands which catalyze highly Z-selective olefin metathesis. A very simple and convenient synthetic procedure of such a catalyst has been developed. An intramolecular C-H bond activation of the NHC ligand, which is promoted by anion ligand substitution, forms the appropriate chelate for stereo- controlled olefin metathesis.

Based on the continued development of well-defined catalysts, olefin metathesis has emerged as a valuable synthetic method for the formation of carbon-carbon double bonds.1 Among the frontiers of catalyst development has been the quest for Z-selective olefin metathesis catalysts which would enable access to complex natural products2 and stereo-regular unique polymers.3 Specifically, the use of Z-selective catalysts in olefin cross-metathesis (CM) represents a promising and useful methodology in organic chemistry. However, due to the thermodynamic nature of metathesis, 4 most catalysts give a higher proportion of the thermodynamically favored E olefin isomer. This fundamental aspect of olefin metathesis has limited its applications in some areas of chemistry.

Recently, some ruthenium-based catalysts which showed enhanced Z-selectivity have been reported, however, their selectivity is still not satisfactory for precisely stereo-controlled syntheses.5 On the other hand, recently developed molybdenum- and tungsten- based catalysts have shown outstanding Z-selectivity in CM2 and metathesis homocoupling6 of terminal olefins. In particular, a bulky aryloxide substituted molybdenum catalyst afforded the cross-coupled product of enol ether and allylbenzene with 98% of the Z isomer. As has been demonstrated in the past, the ruthenium- and molybdenum-based systems show significant differences in selectivities and utility.7

For general use, metathesis catalysts should be not only tolerant towards various functional groups and impurities in reaction media, but also readily synthesized from common reagents by simple reaction steps. Here, we report chelated ruthenium catalysts, which catalyze highly Z-selective olefin metathesis, and their facile synthetic preparation.

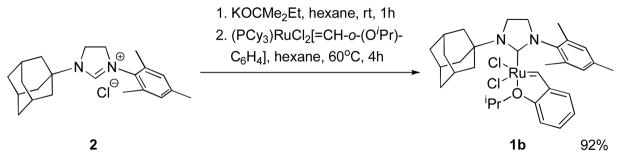

We chose [H2IMes2]RuCl2[=CH-o-(OiPr)C6H4] (1a, H2I = imidazolidinylidene, Mes = mesityl) and the bulkier [H2IMesAdm]-RuCl2[=CH-o-(OiPr)C6H4] (1b, Adm = 1-adamantyl) as precursors. 1b was readily synthesized from commercially available 2 in excellent yield (Scheme 1).8

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 1b

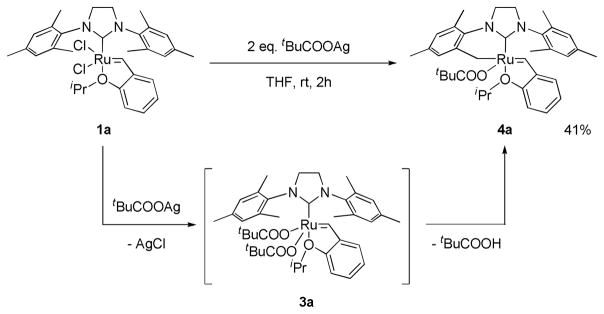

Reaction of 1a with excess silver pivalate resulted in the formation of 3a, which was only observed at early reaction times.9 Subsequent intramolecular C-H bond activation at the methyl position of the mesityl group resulted in the formation of 4a with concomitant release of pivalic acid (Scheme 2). Such intramolecular C-H bond activations assisted by carboxylate ligands have been reported in other organometallic complexes.10 Based on these previous reports, a plausible mechanism for the C-H bond activation in 3a contains 6-membered (A) or 4-membered (B) transition state shown in Figure 1. It should be noted that no other anionic ligands including sulfonate,5b phosphonate,5b and trifluoroacetate11 promote such intramolecular C-H bond activation in 1a. An X-ray crystal structure of 4a clearly indicates the C-H bond activation at the NHC ligand and subsequent formation of the 6-membered chelated complex (Figure 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 4a

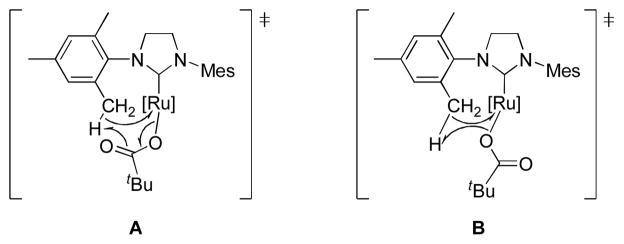

Figure 1.

Plausible transition states of the intramolecular C-H bond activation in 3a.

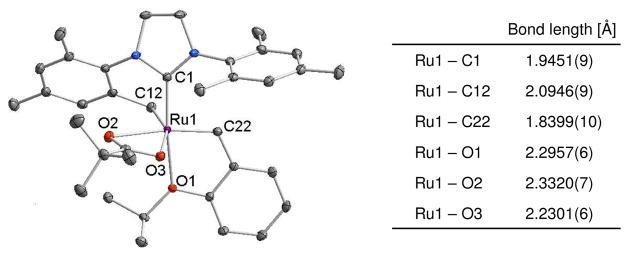

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structure and selected bond length of 4a are shown. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability. For clarity, hydrogen atoms have been omitted.

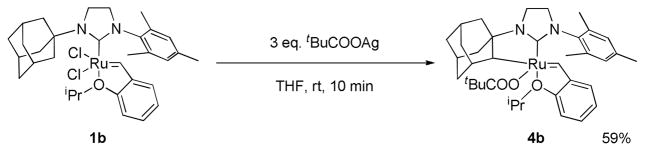

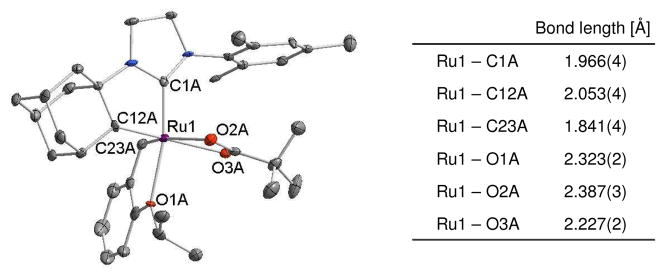

When 1b was reacted with excess silver pivalate, C-H bond activation occurred at the adamantyl group, which resulted in the formation of the 5-membered chelate complex [(C10H14)H2IMes]-RuCl2[=CH-o-(OiPr)C6H4] (4b) (Scheme 3). A dicarboxylate complex was not detected as the C-H bond activation reaction of 1b was too fast, but observation of pivalic acid suggests the same reaction mechanism of intramolecular C-H bond activation. The C-H bond activation at the adamantyl group and the fast reaction may be attributed to the ligand geometry in 1b. An X-ray crystal structure of 1b showed that the adamantyl group is proximal to a vacant coordination site where the C-H bond activation is supposed to occur and the distance between ruthenium and C12, where a new bond forms after C-H bond activation, is relatively short (2.80 Å).12 The molecular structure of 4b determined by X-ray crystallography revealed an adamantyl contained chelate which confirmed the intramolecular C-H bond activation at the adamantyl group (Figure 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 4b

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal structure and selected bond length of 4b are shown. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability. For clarity, hydrogen atoms have been omitted.

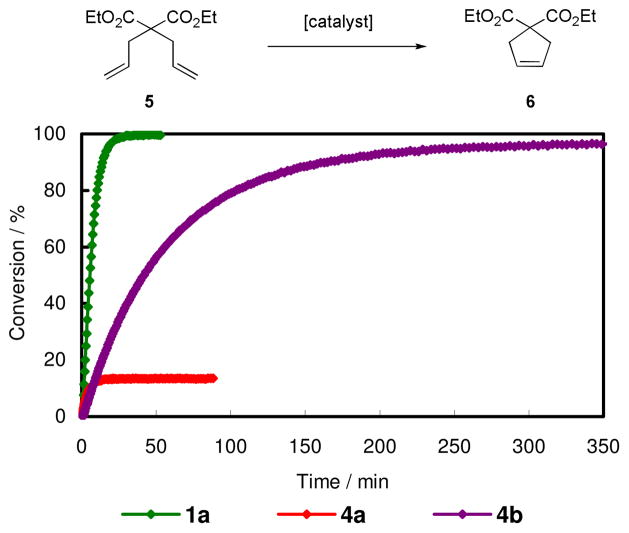

Complexes having chelating NHC ligand derived from intramolecular C-H bond activation have been reported.13 Most of them were formed during catalyst decomposition pathway and none have been reported to have catalytic activity. We investigated at first whether 4a and 4b were still ‘active’ as olefin meta thesis catalysts, testing them in standard ring closing metathesis (RCM) of diethyldiallyl malonate (5)14 and ring opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) of norbornene (7). As shown in Figure 4, both 4a and 4b were metathesis active in the RCM reaction although activities were lower than 1a. Because of catalyst decomposition, the conversion by 4a was limited to ca. 14%. On the other hand, 4b was able to achieve almost full conversion at higher temperature (70 °C). In the ROMP of 7 affording polynorbornene (8), both 4a and 4b also showed high activities at the presented conditions.16

Figure 4.

Plot of conversion versus time for the RCM of 5. Reaction conditions were as follows; 1a15: 1.0 mol % catalyst, 0.1 M substrate, 30 °C, CD2Cl2; 4a: 1.0 mol % catalyst, 0.1 M substrate, 30 °C, C6D6; 4b: 5.0 mol % catalyst, 0.1 M substrate, 70 °C, C6D6.

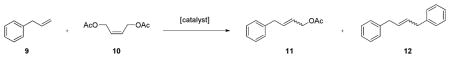

Encouraged by the results of the standard metathesis assays, we then tested the CM of allylbenzene (9) and cis-1,4-diacetoxy-2-butene (10).14 Selected data of the CM are summarized in Table 1. Surprisingly, 4a and 4b gave a much lower E/Z ratio of the cross-coupled product (11) (entry 1 and 2) compared to their parent non-chelate catalysts (entry 6 and 7). The E/Z ratio of 0.12 (90% Z isomer) achieved by 4b is among the lowest reported for ruthenium- based olefin metathesis catalysts. In addition to this, the homocoupled product (12) afforded by 4b also showed significantly low E/Z ratio (E/Z = 0.06, 95% Z isomer). The conversion to 11 was improved under THF reflux condition maintaining excellent Z-selectivity (entry 3). This was probably a result of more efficient removal of ethylene which was generated during the course of reaction. Unexpectedly, addition of water led to higher conversions and selectivity for the Z olefin products (entry 4). This result implies not only that water can be used to optimize reaction conditions but also that 4b is tolerant towards water in organic solvent. Thus, dry solvent is not necessary for 4b in olefin metathesis reactions. This feature enables easy use of the catalyst in common organic syntheses and polymer syntheses without strict reaction conditions. However, 4b decomposed immediately when exposed to oxygen in solution, meaning that degassing of solvent is required to achieve high conversion. Notably, the reaction was reproducible on a synthetic scale (mmol scale, entry 5).

Table 1.

CM of 9 and 10a

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | catalyst | catalyst loading mol %b | solvent | temp °C | time min | 11

|

12

|

||

| conversionc % | E/Zd | conversionc% | E/Zd | ||||||

| 1 | 4a | 2.5 | C6H6 | 23 | 10 | 57.5 | 1.44 | 3.3 | 1.21 |

| 60 | 57.4 | 1.44 | 3.0 | 0.69 | |||||

| 2 | 4b | 5.0 | C6H6 | 70 | 30 | 32.5 | 0.13 | 24.8 | 0.07 |

| 120 | 36.4 | 0.12 | 26.0 | 0.06 | |||||

| 3 | 4b | 5.0 | THF | (reflux) | 240 | 59.5 | 0.19 | 31.6 | 0.04 |

| 4 | 4b | 5.0 | THF/H2Oe | (reflux) | 240 | 64.4 | 0.14 | 28.6 | 0.03 |

| 5f | 4b | 5.0 | THF/H2Oe | (reflux) | 240 | 61.6g | 0.14 | NAh | 0.03 |

| 6 | 1a | 2.5 | C6H6 | 23 | 1 | 69.7 | 10.5 | 5.9 | 5.22 |

| 30 | 66.3 | 10.7 | 10.2 | 6.86 | |||||

| 7 | 1b | 2.5 | C6H6 | 23 | 1 | 0.15 | 3.10 | NAi | NAi |

| 30 | 0.23 | 2.90 | NAi | NAi | |||||

All reactions unless otherwise stated were carried out using 0.20 mmol of 9, 0.40 mmol of 10 and 0.10 mmol of tridecane (internal standard for GC analysis) in 1.0 ml of solvent.

Based on 9.

Conversion of 9 to the product determined by GC analysis.

Molar ratio of E isomer and Z isomer of the product determined by GC analysis.

THF : H2O = 1 : 1 (by volume).

The reaction was carried out using 1.0 mmol of 9, 2.0 mmol of 10 and 0.050 mmol of catalyst in 5.0 ml of solvent.

Isolated yield.

12 was obtained with impurities.

GC signal of 12 was too small to quantify.

In summary, we have demonstrated the utility of chelated ruthenium catalyst for Z-selective olefin cross-metathesis reactions. The Z-selectivity achieved by 4b is the best among reported ruthenium- based catalysts and comparable to the molybdenum- and tungsten-based catalysts. Notably, this is the first time that Z-selectivity in the cross-metathesis of two different olefins has been demonstrated using a ruthenium-based catalyst. The ruthenium catalyst is readily synthesized from common reagents via simple reaction steps and is stable in the presence of water which should promote its application in precisely stereo-controlled organic and polymer syntheses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. B. K. Keitz, Mr. M. B. Herbert and Dr. P. Teo for helpful discussions and suggestions for this work, Materia, Inc. for the generous donation of catalysts and Dr. M. W. Day and Mr. L. M. Henling for X-ray crystallography. The Bruker KAPPA APEXII X-ray diffractometer was purchased via an NSF CRIF:MU award to the California Institute of Technology, CHE-0639094. This work was financially supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH 5R01GM031332-27) and Mitsui Chemicals, Inc.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and X-ray data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Fürstner A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:3012–3043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trnka TM, Grubbs RH. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:18–29. doi: 10.1021/ar000114f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schrock RR. Chem Rev. 2002;102:145–179. doi: 10.1021/cr0103726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:4592–4633. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Samojłowicz C, Bieniek M, Grela K. Chem Rev. 2009;109:3708–3742. doi: 10.1021/cr800524f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Vougioukalakis G, Grubbs RH. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1746–1787. doi: 10.1021/cr9002424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meek SJ, O’brien RV, Llaveria J, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Nature. 2011;471:461–466. doi: 10.1038/nature09957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Flook MM, Jiang AJ, Schrock RR, Muller P, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7962–7963. doi: 10.1021/ja902738u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Flook MM, Gerber LCH, Debelouchina GT, Schrock RR. Macromolecules. 2010;43:7515–7522. doi: 10.1021/ma101375v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Torker S, Müller A, Chen P. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:3762–3766. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Flook MM, Ng VWL, Schrock RR. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;132:1784–1786. doi: 10.1021/ja110949f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grubbs RH, editor. Handbook of Metathesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2003. pp. s1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Rosen EL, Sung DH, Chen Z, Lynch VM, Bielawski CW. Organometallics. 2010;29:250–256. [Google Scholar]; (b) Teo P, Grubbs RH. Organometallics. 2010;29:6045–6050. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Jiang AJ, Zhao Y, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16630–16631. doi: 10.1021/ja908098t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Marinescu SC, Schrock RR, Müller P, Takase MK, Hoveyda AH. Organometallics. 2011;30:1780–1782. doi: 10.1021/om200150c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortez GA, Baxter CA, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Org Lett. 2007;9:2871–2874. doi: 10.1021/ol071008h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jafarpour L, Hillier AC, Nolan SP. Organometallics. 2002;21:442–444. [Google Scholar]

- 9.3a was detected by 1H NMR and FD-MS. See details in the Supporting Information.

- 10.(a) Davies DL, Donald SMA, Al-Duaij O, Macgregor SA, Pölleth M. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4210–4211. doi: 10.1021/ja060173+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li L, Brennessel WW, Jones WD. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12414–12419. doi: 10.1021/ja802415h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li L, Brennessel WW, Jones WD. Organometallics. 2009;28:3492–3500. [Google Scholar]; (d) Tsurugi H, Fujita S, Choi G, Yamagata T, Ito S, Miyasaka H, Mashima K. Organometallics. 2010;29:4120–4129. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krause JO, Nuyken O, Wurst K, Buchmeiser MR. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:777–784. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For X-ray crystal structure and selected bond length of 1b, see the Supporting Information.

- 13.(a) Trnka TM, Morgan JP, Sanford MS, Wilhelm TE, Scholl M, Choi TL, Ding S, Day MW, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:2546–2558. doi: 10.1021/ja021146w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Leitao EM, Dubberley SR, Piers WE, Wu Q, McDonald R. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:11565–11572. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritter T, Hejl A, Wenzel AG, Funk TW, Grubbs RH. Organometallics. 2006;25:5740–5745. [Google Scholar]

- 15.The RCM data was referred to ref. 14.

- 16.For the reaction conditions and results, see the Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.