Abstract

Objective: To investigate the specific effect of adjunctive aripiprazole on sexual function in patients with major depressive disorder and a history of an inadequate response to antidepressant medication by controlling for improvement in depressive symptoms as measured by improvement in Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total scores.

Method: For this post hoc analysis, data were pooled from 3 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled aripiprazole augmentation studies (CN138-139: June 2004–April 2006; CN138-163: September 2004–December 2006; and CN138-165: March 2005–April 2008). Outpatients who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for a major depressive episode that had lasted ≥8 weeks with an inadequate response to prospective antidepressant treatment were randomized to adjunctive aripiprazole or placebo for 6 weeks. Sexual functioning was assessed using the Massachusetts General Hospital Sexual Functioning Inventory (MGH-SFI). To assess whether adjunctive aripiprazole improves sexual functioning directly, rather than as an indirect effect of improvement in depression symptoms, the mean change in MGH-SFI item scores and overall improvement scores was assessed using analysis of covariance, with double-blind baseline and change in MADRS total score as covariates. Correlations between MGH-SFI items and MADRS total score and prolactin levels were also assessed.

Results: The analysis included 1,092 subjects (n=737 female and n=355 male). In the total population, adjunctive aripiprazole demonstrated statistically significant greater improvements versus placebo on the MGH-SFI item “interest in sex” (−0.34 vs −0.18, P<.05). In males, no significant treatment differences were observed. In females, improvements in sexual functioning with adjunctive aripiprazole versus placebo were found on the MGH-SFI items “interest in sex” (−0.41 vs −0.21, P<.05) and “sexual satisfaction” (−0.44 vs −0.25, P<.05).

Conclusions: Aripiprazole adjunctive to antidepressant treatment can have some beneficial effects on sexual functioning in patients with major depressive disorder who respond inadequately to standard antidepressant treatment; the benefits in women were specific to sexual interest and satisfaction and were independent of the improvement in depressive symptoms.

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifiers: NCT00095823, NCT00095758, and NCT00105196

Impairment in sexual functioning is common in patients with depression. Indeed, studies have shown that sexual dysfunction is a key component of depression, with an increased risk even when controlling for age, health, medication, and other variables.1,2 It is also widely recognized that antidepressant therapy (ADT) can contribute to the emergence or exacerbation of sexual dysfunction. In addition, sexual side effects have been reported to occur, in varying degrees, with some medications across several antidepressant classes.3 However, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), along with the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) such as venlafaxine and the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) clomipramine, are the antidepressants most commonly associated with the adverse effect of sexual dysfunction.4 Common sexual side effects reported during ADT include erectile dysfunction, diminished libido, arousal difficulties, ejaculatory dysfunction, and delayed or absent orgasm,5 although the effects vary with agent as well as between the sexes. It should also be considered that the incidence and type of sexual dysfunction varies between antidepressants in the same class due todifferences in their pharmacologic profiles. For example, among the SSRIs, the high selectivity of paroxetine for serotonin reuptake relative to dopamine reuptake may explain the higher reported incidence of sexual dysfunction with paroxetine relative to other SSRIs.3,5

Clinical Points

♦All health care professionals involved in the treatment of major depressive disorder should be aware that sexual dysfunction is common, can be exacerbated by some treatments, and may lead to premature discontinuation of medication.

♦Sexual dysfunction should be monitored and managed appropriately in all patients.

♦Adjunctive aripiprazole is associated with modest beneficial effects on sexual functioning in some patients, especially women.

Treatment-associated sexual dysfunction can have a range of potential consequences, including psychological distress, a negative impact on quality of life, and self-esteem and relationship difficulties.3 Sexual dysfunction is also a common reason for medication nonadherence, resulting in treatment failure and costly disease management outcomes.6 Data suggest that up to 90% of patients with treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction will discontinue their prescribed medication prematurely.6 Taken together, improvement in sexual function should be considered an important goal in the treatment of depression, and steps should be taken to manage antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction if it occurs. The management of sexual dysfunction in patients with depression should start with establishing the etiology of the problem and determining any temporal relationship between the onset of the problem and depressive symptoms, treatment effects, or other factors that may impact on sexual functioning.7 General guidelines for managing antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction have been proposed and include reducing the antidepressant dose, switching treatment to an agent with a more favorable side effect profile, nonpharmacologic (psychotherapeutic) interventions, or addition of adjunctive medication to counter the effects of antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction.3,7

Aripiprazole is an atypical antipsychotic that is approved as an adjunctive agent to ADT for the treatment of depression. The efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy to ADT has been demonstrated in 3 large, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials involving patients who presented with a history of inadequate response to at least 1 trial of ADT and who exhibited an inadequate response to a prospective 8-week trial of a different ADT.8–10 Aripiprazole has a unique pharmacologic profile: partial agonist activity at dopamine D2, D3, and serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and antagonist activity at 5-HT2A receptors.11 This pharmacologic profile mayhave beneficial effects on sexual functioning in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) who have an inadequate response to standard ADT.3 For example, bupropion, an inhibitor of both the norepinephrine and dopamine transporters, has been shown in some studies to reduce SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction,12 whereas antagonism at 5-HT2A receptors is seen with other antidepressants (such as nefazodone and mirtazapine), which are associated with a low incidence of sexual dysfunction.4 Aripiprazole monotherapy has also been shown to improve sexual functioning, as measured by mean improvement in Arizona Sexual Experience scale (ASEX) scores, in community-treated patients with schizophrenia.13 Thus, it was hypothesized that adjunctive aripiprazole has the potential to improve sexual functioning in patients with MDD.

Although medication-induced hyperprolactinemia is less likely with the atypical antipsychotics than typical agents,14 it has been reported commonly in women treated with SSRIs15 and can be associated with a wide range of clinical symptoms including sexual dysfunction. Thus, it has been suggested that reducing medication-induced hyperprolactinemia in patients with psychiatric disorders may improve sexual functioning.16 Given that aripiprazole, both as monotherapy and adjunctive to antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia, has been associated with decreases in mean prolactin levels,13,17 it was also hypothesized that potential improvements in sexual functioning with adjunctive aripiprazole may be correlated with decreases in prolactin levels.

Here, we present a post hoc analysis of pooled data from 3 double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials conducted with aripiprazole that had the mean change in Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total scores as the primary endpoint. As reported previously,8–10 in the original individual studies at the end of the double-blind treatment phase, the mean change in the MADRS total scores was significantly greater in patients receiving adjunctive aripiprazole (−8.5 to −10.1) compared with placebo (−5.7 to −6.4, all P≤001). This post hoc analysis was designed to assess the direct impact of adjunctive aripiprazole treatment on sexual functioning in patients with MDD and a historyof an inadequate response to antidepressant medication by controlling for improvement in depressive symptoms as measured by improvement in MADRS total scores.

METHOD

Data were pooled from 3 placebo-controlled studies conducted at multiple sites within the United States. All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received appropriate approval by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before study entry.

Study Design and Patient Population

Full details of the primary studies have been described previously.8–10 Briefly, 3 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (CN138-139: June 2004–April 2006; CN138-163: September 2004–December 2006; and CN138-165: March 2005–April 2008) were conducted to investigate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of adjunctive aripiprazole with standard ADT in patients with MDD who showed an inadequate response (defined as <50% reduction in severity of depressive symptoms) to at least 1 historical and 1 prospective ADT. The studies are registered in clinicaltrials.gov (identifiers: NCT00095823, NCT00095758, and NCT00105196).

Subjects were outpatients, aged 18–65 years, who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for a major depressive episode18 that had lasted ≥8 weeks. Patients were also required to have reported inadequate response to a previous adequate trial of ADT (defined as <50% reduction in severity of depressive symptoms—determined by the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire [ATRQ]19—to at least 1 and no more than 3 ADT trials of >6 weeks duration [monotherapy] or >3 weeks duration [combination treatments] at the minimum dose specified in the ATRQ). Further details of inclusion and exclusion criteria have been reported previously.8–10

Each study consisted of 3 phases: a 7- to 28-day screening phase, an 8-week prospective standard ADT treatment phase, and a 6-week double-blind randomization phase (actual study visits weeks 9–14). During the prospective ADT treatment phase, patients were treated with either escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine controlled release, sertraline, or venlafaxine extended release, given according to label dosing. Patients also received single-blind placebo treatment in this phase to blind the patients to the transition into the randomized, double-blind treatment phase. For continuation into the double-blind treatment phase, patients in all studies were required to have an inadequate response to 8 weeks of prospective ADT treatment—defined as a <50% reduction in 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17) total score during prospective ADT treatment and a HDRS-17 score ≥14 and a Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement of illness scale (CGI-I) score ≥3 at randomization (week 8). Patients in study CN138-165 were also required to have a CGI-I score ≥3 at study week 6. Patients meeting criteria for entry into double-blind treatment were randomized (1:1) to continue the same ADT plus either double-blind adjunctive placebo or adjunctive aripiprazole (2–20 mg/d). Aripiprazole was started at 5 mg/d and increased in weekly 5-mg/d increments to a maximum of 15 mg/d (patients receiving paroxetine or fluoxetine) or 20 mg/d (all other patients) based on assessment of efficacy and clinical response. Aripiprazole doses could be decreased at any visit on the basis of tolerability, except in the last week of double-blind treatment.

Assessments

Patients were evaluated weekly for the 6-week duration of double-blind treatment. The primary efficacy measure in these studies was the mean change from the end of the prospective ADT treatment phase (double-blind baseline, week 8) to the end of the randomized, double-blind phase (week 14) in the MADRS total score.20

Sexual functioning was assessed using the Massachusetts General Hospital Sexual Functioning Inventory (MGH-SFI).21 This is a patient-rated self-report outcome measure that quantifies sexual dysfunction into 5 functional domains (“interest in sex,” “sexual arousal,” “ability to achieve orgasm,” “ability to maintain erection” [males only], and “sexual satisfaction”). Patients rate each item at the start of prospective ADT treatment (week 0), the end of the prospective ADT treatment phase (double-blind baseline, week 8), and week 14 using a 6-point scale from 1 (good function) to 6 (poor function). Overall improvement since their last medication change was also measured at the end of the prospective ADT treatment phase (double-blind baseline, week 8) and week 14 using a 6-point scale (1=very much improved, 2=much improved, 3=minimally improved, 4=unchanged, 5=minimally worse, 6=much worse). Serum blood samples were drawn at screening and at study weeks 8 and 14 to determine serum prolactin levels.

Analyses

For this post hoc analysis, data were pooled from patients who participated in 3 aripiprazole studies. All analyses were conducted on the safety sample, which included all patients who received at least 1 dose of study medication (adjunctive aripiprazole or adjunctive placebo) during the 6-week, double-blind treatment phase. In these analyses, double-blind baseline was defined at the end of the prospective ADT treatment phase, just prior to receiving double- blind study medication. Analyses were conducted on the last-observation-carried-forward data set.

To assess how the treatment effect on sexual functioning might be impacted by improvement in depressive symptoms, this analysis was conducted on the change in MGH-SFI scores at endpoint, in which an adjustment for change in MADRS total score was included in the statistical model. Mean change in MGH-SFI item scores and overall improvement scores were assessed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with double-blind treatment and study as main effects and double-blind baseline MADRS total score assessment and change from double-blind baseline in MADRS total score as covariates. Separate analyses were also conducted for male and female subjects using the same ANCOVA model, controlling for depressive symptoms at double-blind baseline and their improvement with treatment.

Correlations between MGH-SFI items and MADRS total score or prolactin levels were made using Pearson's product-moment correlation.

RESULTS

Subject Disposition and Characteristics

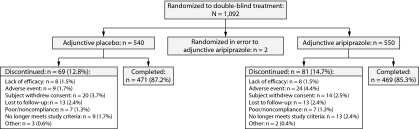

A total of 1,092 patients were randomized to double-blind treatment in these 3 studies; 540 patients received adjunctive placebo, 550 patients received adjunctive aripiprazole, and an additional 2 patients were randomized to aripiprazole treatment in error. Patient disposition of the combined data set is shown in Figure 1. The randomized, double-blind treatment phase was completed by 85.3% of adjunctive aripiprazole-treated patients and 87.2% of adjunctive placebo-treated patients. The most common reasons for withdrawal were withdrawal of consent (3.7%) in the adjunctive placebo group and adverse events (4.4%) in the adjunctive aripiprazole group. Overall, 1,085 patients (adjunctive placebo, n=538; adjunctive aripiprazole, n=547) received at least 1 dose of study medication and were included in the safety sample, of whom 990 patients (adjunctive placebo, n=489; adjunctive aripiprazole, n=501) had at least 1 MGH-SFI item rating score for inclusion in this post hoc analysis.

Figure 1.

Pooled Patient Disposition (randomized sample)

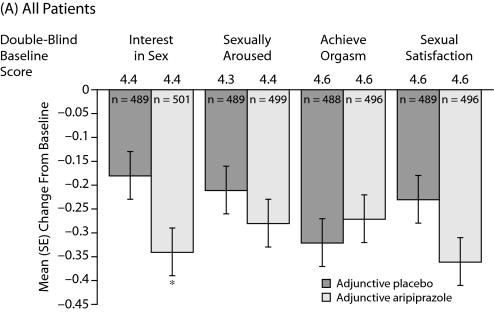

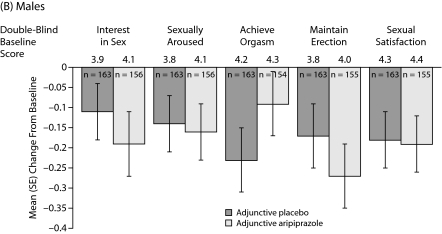

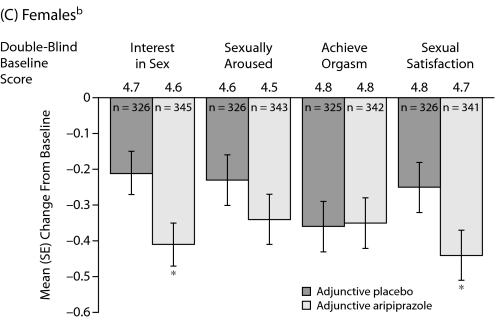

aMean change in MGH-SFI item scores from double-blind baseline were assessed using analysis of covariance, with double-blind treatment and study as main effects and double-blind baseline assessment and change from double-blind baseline in Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale total score as covariates.

bSafety sample, last observation carried forward.

*P<.05 vs placebo.

Abbreviation: MGH-SFI=Massachusetts General Hospital-Sexual Functioning Inventory.

Patient demographic characteristics for the pooled sample are shown in Table 1. There were no clinically relevant differences between the treatment groups across demographic characteristics. The mean age of patients was approximately 45 years, more females (n=737) than males (n=355) were randomized to treatment, and the majority (88.7%) of patients were white.

Table 2.

Correlation Between Change in MGH-SFI Item Scores and Change in MADRS Total Score and Prolactin Level (safety sample)a

| Change inMADRS Total Score | Change in Prolactin Level | |||

| Correlation | Adjunctive Placebo | Adjunctive Aripiprazole | Adjunctive Placebo | Adjunctive Aripiprazole |

| Total population | ||||

| Interest in sex | 0.217 | 0.211 | −0.064 | −0.091 |

| Sexually aroused | 0.185 | 0.219 | −0.053 | −0.008 |

| Achieve orgasm | 0.168 | 0.193 | −0.059 | −0.073 |

| Sexual satisfaction | 0.167 | 0.241 | −0.065 | −0.099 |

| Overall improvement | 0.301 | 0.372 | −0.069 | −0.069 |

| Females | ||||

| Interest in sex | 0.196 | 0.194 | −0.065 | −0.064 |

| Sexually aroused | 0.184 | 0.227 | −0.063 | −0.001 |

| Achieve orgasm | 0.170 | 0.195 | −0.085 | −0.024 |

| Sexual satisfaction | 0.148 | 0.208 | −0.074 | −0.063 |

| Overall improvement | 0.253 | 0.375 | −0.091 | −0.019 |

| Males | ||||

| Interest in sex | 0.276 | 0.224 | −0.049 | −0.100 |

| Sexually aroused | 0.186 | 0.179 | 0.029 | 0.085 |

| Achieve orgasm | 0.157 | 0.152 | 0.118 | −0.145 |

| Maintain erection | 0.160 | 0.152 | −0.007 | 0.070 |

| Sexual satisfaction | 0.223 | 0.295 | −0.001 | −0.101 |

| Overall improvement | 0.416 | 0.327 | 0.038 | −0.064 |

Bolded values represent P<.05.

Abbreviations: MADRS=Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, MGH-SFI=Massachusetts General Hospital-Sexual Functioning Inventory.

Among patients who entered the prospective ADT treatment phase of the studies, the frequency of ADT selection was venlafaxine extended release (29.5%), escitalopram (27.9%), sertraline (19.1%), fluoxetine (14.5%), and paroxetine controlled release (9.0%). The distribution of ADT during the double-blind treatment phase was similar (venlafaxine extended release [27.8%], escitalopram [30.5%], sertraline [18.2%], fluoxetine [15.0%], and paroxetine controlled release [8.5%]) and was comparable between treatment groups.

Table 1.

Pooled Patient Demographics (randomized sample)

| Characteristic | Adjunctive Placebo | Adjunctive Aripiprazole |

| Patients, n | 540 | 552a |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 181 (33.5) | 174 (31.5) |

| Female | 359 (66.5) | 378 (68.5) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 44.7 (10.9) | 45.4 (10.8) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 483 (89.4) | 486 (88.0) |

| Black | 42 (7.8) | 43 (7.8) |

| Asian | 6 (1.1) | 9 (1.6) |

| American Indian/Alaskan native | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 0 | 3 (0.5) |

| Other | 7 (1.3) | 9 (1.6) |

| Duration of current episode, mo | ||

| Median (range) | 18.8 (1.6–678.8) | 18.8 (1.7–474.1) |

| Single depressive episode, n (%) | 109 (20.2) | 99 (17.9) |

| No. of adequate trials in current episode, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 5 (0.9) | 3 (0.5) |

| 1 | 363 (67.2) | 385 (69.8) |

| 2 | 142 (26.3) | 132 (24.0) |

| 3 | 27 (5.0) | 30 (5.4) |

| ≥4 | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

Includes 2 subjects who were randomized to aripiprazole treatment in error.

Sexual Functioning: All Patients

Mean changes in MGH-SFI items during double-blind treatment are shown in Figure 2A–2C. In the total population, adjunctive aripiprazole demonstrated statistically significant greater improvements versus adjunctive placebo on the MGH-SFI item “interest in sex” (−0.34 vs −0.18, P<.05) (Figure 2A). Improvement in sexual functioning was independent of improvement in depressive symptoms, as double-blind baseline MADRS total score and change from double-blind baseline in MADRS total score were included in the ANCOVA model as covariates.

Figure 2.

Mean (SE) Change in MGH-SFI Items During Double-Blind Treatmenta,b

aOverall improvement since their last medication change rated on a 6-point scale (1=very much improved to 6=much worse).

bMean double-blind baseline scores—all patients: placebo 3.8, aripiprazole 3.8; females: placebo 3.8, aripiprazole 3.8; and males: placebo 3.9, aripiprazole 3.8.

cMean MGH-SFI overall improvement scores were assessed using analysis of covariance, with double-blind treatment and study as main effects and double-blind baseline assessment and change from double-blind baseline in Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale total score as covariates. Differences were not statistically significant.

Abbreviation: MGH-SFI=Massachusetts General Hospital-Sexual Functioning Inventory.

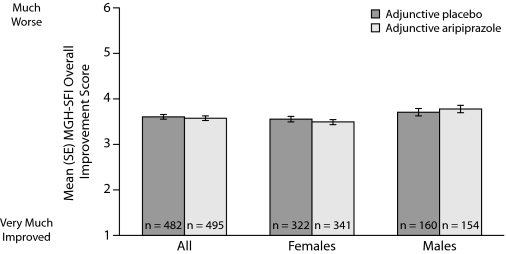

MGH-SFI ratings of overall improvement since medication change are shown in Figure 3; the differences between adjunctive aripiprazole treatment compared with adjunctive placebo treatment were not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Overall Improvement in Sexual Functioning Since Medication Change at Week 14 (safety sample, last observation carried forward)a,b,c

Sexual Functioning: Males

Mean changes in MGH-SFI items during double-blind treatment in males are shown in Figure 2B. Adjunctive aripiprazole demonstrated only numerical improvements versus adjunctive placebo on the following MGH-SFI items in males: “interest in sex,” “ability to get sexually aroused,” “ability to maintain erection,” and “sexual satisfaction.” None of these changes reached statistical significance. Overall improvement since medication change was also not significantly different between treatment groups in males (Figure 3).

Sexual Functioning: Females

Mean changes in MGH-SFI items during double-blind treatment in females are shown in C. Adjunctive aripiprazole demonstrated statistically significant improvement versus adjunctive placebo on the MGH-SFI items “interest in sex” and “sexual satisfaction” in females (−0.41 vs −0.21 and −0.44 vs −0.25, respectively, P<.05). Again, this improvement in sexual functioning was independent of improvement in depressive symptoms, which was adjusted for in the statistical model. Adjunctive aripiprazole demonstrated comparable overall improvement since medication change to adjunctive placebo in females (Figure 3).

Correlation Between Change in MGH-SFI Item Scores and Change in MADRS Total Score and Prolactin Levels

Correlation coefficients (r) between changes in MGH-SFI item and change in MADRS total scores or change in prolactin levels are shown inTable 2 . In the total population, there was a statistically significant, moderate correlation between improvement in the MADRS total score and improvement in all MGH-SFI item scores in both treatment groups (P<.05). In females, improvement in all 5 MGH-SFI item scores showed a statistically significant, moderate correlation with improvement in MADRS total scores in the adjunctive aripiprazole and adjunctive placebo groups, whereas in males, there was a statistically significant, moderate correlation between improvement in the MADRS total score and improvement in all MGH-SFI item scores in the adjunctive placebo group (P<.05). In the adjunctive aripiprazole group, there was no significant correlation in “ability to maintain erection” or “ability to achieve orgasm.”

In the total population, significant, but weak, negative correlation was seen between change in prolactin scores and the MGH-SFI items “interest in sex” and “sexual satisfaction” in the adjunctive aripiprazole group (P<.05). No other MGH-SFI items showed significant correlation with change in prolactin levels in either the total population or analysis by gender.

DISCUSSION

Results from this post hoc analysis of pooled data from 3 randomized, controlled trials of aripiprazole augmentation of ADT suggest that adjunctive aripiprazole is associated with modest beneficial effects on sexual functioning in some patients. These benefits were manifested primarily by significant improvement in “interest in sex” and “sexual satisfaction” in women after treatment with adjunctive aripiprazole compared with those treated with placebo. Importantly, the improvement in sexual functioning was independent of improvements in depressive symptoms.

Impairment of sexual functioning is frequently associated with major depression,12 and treatments have also been shown to contribute to the emergence or exacerbation of sexual dysfunction, particularly SSRIs, SNRIs, and TCAs.3 In this analysis, perhaps not surprisingly, statistically significant correlations were observed between improvement in depression symptoms and improvement in sexual functioning for the majority of sexual functioning items in both men and women. To further explore the relationship between improvements in sexual functioning and depression symptoms following treatment with aripiprazole, further analyses of the changes in MGH-SFI items were carried out, controlling for improvements in depressive symptoms. When controlling for the change in MADRS total score from double-blind baseline, improvements in sexual functioning following adjunctive aripiprazole treatment were not statistically significant in men. This may be due to the fact that there were too few men in the analysis to achieve sufficient statistical power or that aripiprazole has less effect on the physical components of sexual function in men. On the item “achieve orgasm,” adjunctive aripiprazole patients reported less improvement than the adjunctive placebo patients, suggesting that adjunctive aripiprazole in men will not worsen sexual function compared with ADT monotherapy.

In contrast, improvements in sexual functioning were shown to occur independently of improvement in depressive symptoms on the 2 MGH-SFI items related to libido and sexual satisfaction. The finding that adjunctive aripiprazole can improve sexual function in women independently of the benefits on depression itself suggests a potential direct effect of aripiprazole on sexual functioning in women with MDD. Diminished sexual function in women is usually multifactorial and associated with a variety of psychological factors, such as the quality of interpersonal relationships, body image, sexual self-esteem, and prior psychosexual adjustment, so the findings have clinical relevance for clinicians considering adjunctive aripiprazole for their patients who do not respond to ADT.22 MGH-SFI ratings of overall improvement since medication change were not significantly different between adjunctive aripiprazole and adjunctive placebo in men or women, although the sensitivity of this question for detecting improvements in sexual functioning with treatment has not been systematically evaluated.

It is interesting to note that sexual functioning improvements in women were mainly seen on the more emotional components of sexual functioning, specifically, improvements in libido and sexual satisfaction items of the MGH-SFI. In considering reasons for a gender-specific effect, one possibility is that improvements in sexual functioning may be related to the enhanced dopaminergic effects of aripiprazole when added to ADT, especially as dopamine is known to have a positive effect on sexual desire and arousal in women and may promote willingness to continue sexual activity after it is initiated.22

In support of this hypothesis, preclinical studies have demonstrated that aripiprazole adjunctive to the SSRI escitalopram reversed the inhibitory action of escitalopram on the firing rate of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine neurons. As the firing rates of serotonin and dopamine neurons were not diminished by the combination of escitalopram and aripiprazole, the direct 5-HT1A and D2 agonistic activity of aripiprazole may contribute to enhancing overall serotonin and dopamine transmission.23 It is also possible that the partial agonist activity of aripiprazole at dopamine D2 and D3 receptors may further enhance dopaminergic activity in patients with depression. Women may respond better to the type of sexual dysfunction improved by treatment with dopamine-modulating agents, reflecting differences in the endocrinology and the physiology of the normal sexual response cycle between men and women. It is quite possible that sexual satisfaction in women is affected more by improvements in libido as compared to men, in whom sexual satisfaction may more closely reflect improvements in the more physical aspects of sexuality, such as ability to achieve orgasm or maintain erection. Further study is needed to better understand the mechanisms underlying the improvement in sexual functioning observed with aripiprazole and to examine potential reasons for the differential effect between men and women.

Similar to the findings reported here, bupropion—a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor without direct effects on serotonergic neurotransmission—has also been shown to increase the desire to engage in sexual activity, as well as to increase the frequency of engaging in sexual activity, but not other aspects of sexual functioning.12 It is also interesting to note that flibanserin, a drug that was initially developed as an antidepressant, has been shown to be effective for the treatment of premenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder.24,25 Flibanserin is an agonist at serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and an antagonist at serotonin 5-HT2A receptors and is thought to act by modulating dopamine and norepinephrine neurotransmitter systems, thereby leading to a healthy sexual response.26,27

Previous findings from a 26-week open-label study in patients with schizophrenia have shown that aripiprazole treatment was associated with improvements in sexual functioning using the ASEX scale as well as mean decreases in serum prolactin levels, although no meaningful correlation was found between sexual functioning and prolactin levels.13 Similarly, our study also failed to show a consistent correlation between changes in prolactin levels and changes in sexual functioning. Thus, it seems unlikely that reduction in prolactin levels with adjunctive aripiprazole treatment contributed to the improvements in sexual functioning experienced in these patients, especially since that correlation was not observed on the MGH-SFI in women who showed greatest improvement with treatment. However, of note, studies relating hyperprolactinemia with sexual dysfunction have found more of an association in men than in women, suggesting that men may be more sensitive than women to hyperprolactinemia-related sexual dysfunction.14

The findings of this study should be considered with several limitations in mind. First, the study did not attempt to identify the possible underlying causes of sexual dysfunction, which is a consideration given the well-known impact of both mental and physical illnesses on sexual functioning,28 and the analyses did not make any distinction between patients who may have ADT-induced sexual dysfunction or depression-induced sexual dysfunction. However, given that the improvements observed were independent of change from double-blind baseline in MADRS total score, we can hypothesize that adjunctive aripiprazole treatment helped to ameliorate ADT-induced sexual dysfunction. Further studies will be necessary to establish which specific types of sexual dysfunction benefit from adjunctive treatment with aripiprazole and to establish explicitly whether improvement is specific to ADT-induced sexual dysfunction or to sexual dysfunction consequent to depression.

Second, this study used the MGH-SFI, which is derived from the ASEX, to assess sexual functioning. Although the MGH-SFI has been validated in male psychiatric patients,21 it has not been specifically validated in female patients. Third, these studies were not powered to detect differences in MGH-SFI items, and, thus, all significant values should be considered exploratory and with this limitation in mind. Fourth, treatment effects were modest, and the clinical significance of observed improvement is unknown. Fifth, the effects on sexual functioning of aripiprazole as an adjunct to individual ADTs were not evaluated; the benefits of adjunctive aripiprazole may vary based on the types of antidepressants and their underlying propensity to cause sexual dysfunction.

Sixth, data from this analysis came from controlled clinical trials in a defined, predominantly white patient population. With this in mind, the findings may not generalize to a wider patient population, for example, those in an earlier stage of treatment or patients with concurrent medical conditions that may impact sexual function. Finally, individual variability in prolactin levels may account for the lack of a consistent significant correlation between change in sexual function and prolactin; thus, the importance of prolactin and sexual dysfunction should not be dismissed.

In conclusion, patients in the present post hoc analysis identified as inadequate responders to ADT, and thus eligible for treatment with adjunctive aripiprazole or adjunctive placebo, had moderate sexual dysfunction at double-blind baseline. Adjunctive aripiprazole had a significant positive effect on some of the more emotional components of sexual functioning in women—namely, libido and sexual satisfaction—that were largely independent of improvement in depressive symptoms.

Drug names: aripiprazole (Abilify), bupropion (Aplenzin, Wellbutrin, and others), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), mirtazapine (Remeron and others), paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva, and others), sertraline (Zoloft and others), venlafaxine (Effexor and others).

Potential conflicts of interest: Dr Fava has received grant/research support from Abbott, Alkermes, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, BioResearch, Brain Cells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Clinical Trial Solutions, Eli Lilly, Forest, Ganeden, GlaxoSmithKline, J & J, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex, NARSAD, National Center for Complimentary and Alternative Medicine, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, Novartis, Organon, PamLab, Pfizer, Pharmavite, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Shire, Solvay, Synthelabo, and Wyeth-Ayerst; has served as a consultant to or on the advisory boards of Abbott, Amarin, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Auspex, Bayer AG, Best Practice Project Management, BioMarin, Biovail, BrainCells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Clinical Trials Solutions, CNS Response, Compellis, Cypress, Dov, Eisai, Eli Lilly, EPIX, Euthymics Bioscience, Fabre-Kramer, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Grunenthal GmBH, Janssen, Jazz, J & J, Knoll, Labopharm, Lorex, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, Methylation Sciences, Neuronetics, Novartis, Nutrition 21, Organon, PamLab, Pfizer, PharmaStar, Pharmavite, Precision Human Biolaboratory, PsychoGenics, Psylin Neurosciences, Ridge Diagnostics, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Solvay, Somaxon, Somerset, Synthelabo, Takeda, Tetragenex, TransForm, Transcept, Vanda, and Wyeth-Ayerst; has had speaking/publishing affiliations with Adamed, Advanced Meeting Partners, American Psychiatric Association, American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, AstraZeneca, Belvoir, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Imedex, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Primedia, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Reed-Elsevier, Novartis, Organon, Pfizer, PharmaStar, UBC, and Wyeth-Ayerst; has equity holdings in Compellis; receives copyright royalties for the Massachusetts General Hospital Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire (CPFQ), the Discontinuation Emergent Signs Symptoms (DESS) scale, and the SAFER criteria interview; and has patent applications for SPCD and for a combination of azapirones and bupropion in major depressive disorder. Dr Dording has received research support from Abbott, Alkermes, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, J & J, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex, Novartis, Organon, PamLab, Pfizer, Pharmavite, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Solvay, Synthelabo, and Wyeth-Ayerst; has served as a consultant to or on the advisory board of Takeda; and has served on the speakers bureau of Wyeth-Ayerst. Drs Baker, Berman, and Mankoski and Mr Eudicone are employees of and stock shareholders in Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr Owen is a former employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr Tran is a former employee and Dr Forbes is a current employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization.

Funding/support: This study was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, New Jersey, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan. Editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Ogilvy Healthworld Medical Education; funding for editorial support was provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Previous presentation: Presented in part at the 160th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 19–24, 2007; San Diego,California; and the Institute on Psychiatric Services meeting; October 2–5, 2008; Chicago, Illinois.

REFERENCES

- 1.Araujo AB, Durante R, Feldman HA, et al. The relationship between depressive symptoms and male erectile dysfunction: cross-sectional results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(4):458–465. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199807000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy SH, Dickens S.E., Eisfeld B.S., et al. Sexual dysfunction before antidepressant therapy in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1999;56(2-3):201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fava M, Rankin M.Sexual functioning and SSRIs J Clin Psychiatry 200263suppl 513–16,.discussion 23–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montejo AL, Llorca G., Izquierdo J.A., et al. Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction. Incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multicenter study of 1,022 outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 3):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lane RM. A critical review of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-related sexual dysfunction; incidence, possible aetiology and implications for management. J Psychopharmacol. 1997;11(1):72–82. doi: 10.1177/026988119701100117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nurnberg HG. An evidence-based review updating the various treatment and management approaches to serotonin reuptake inhibitor-associated sexual dysfunction. Drugs Today (Barc) 2008;44(2):147–168. doi: 10.1358/dot.2008.44.2.1191059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zajecka J. Strategies for the treatment of antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 3):35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berman RM, Marcus R.N., Swanink R., et al. The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(6):843–853. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcus RN, McQuade R.D., Carson W.H., et al. The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a second multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(2):156–165. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31816774f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berman R.M., Fava M., Thase M.E., et al. Aripiprazole augmentation in major depressive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(4):197–206. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900020216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burris K.D., Molski T.F., Xu C., et al. Aripiprazole, a novel antipsychotic, is a high-affinity partial agonist at human dopamine D2 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302(1):381–389. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.033175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clayton A.H., Warnock J.K., Kornstein S.G., et al. A placebo-controlled trial of bupropion SR as an antidote for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor–induced sexual dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(1):62–67. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanssens L., L'Italien G., Loze J.Y., et al. The effect of antipsychotic medication on sexual function and serum prolactin levels in community-treated schizophrenic patients: results from the Schizophrenia Trial of Aripiprazole (STAR) study ( NCT00237913) BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8(1):95. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byerly M., Suppes T., Tran Q.V., et al. Clinical implications of antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia in patients with schizophrenia spectrum or bipolar spectrum disorders: recent developments and current perspectives. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):639–661. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31815ac4e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papakostas G.I., Miller K.K., Petersen T., et al. Serum prolactin levels among outpatients with major depressive disorder during the acute phase of treatment with fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(6):952–957. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahl J., Kinon B.J., Liu-Seifert H. Sexual dysfunction associated with neuroleptic-induced hyperprolactinemia improves with reduction in prolactin levels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1032(1):289–290. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kane J.M., Correll C.U., Goff D.C., et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 16-week study of adjunctive aripiprazole for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder inadequately treated with quetiapine or risperidone monotherapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(10):1348–1357. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05154yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. Text Revision. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(8):649–659. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montgomery S.A., Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134(4):382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Labbate L.A., Lare S.B. Sexual dysfunction in male psychiatric outpatients: validity of the Massachusetts General Hospital Sexual Functioning Questionnaire. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70(4):221–225. doi: 10.1159/000056257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clayton A.H. Sexual function and dysfunction in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26(3):673–682. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(03)00043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chernoloz O., El Mansari M., Blier P. Electrophysiological studies in the rat brain on the basis for aripiprazole augmentation of antidepressants in major depressive disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;206(2):335–344. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1611-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pyke R., Cotton D., Kennedy S., et al. Washington: DC; May 3–8, 2008. Flibanserin: a novel centrally acting agent that is not an effective antidepressant but has potential to treat decreased sexual desire in women. American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting New Research Abstracts (NR5–119). 160th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jolly E., Clayton A.H., Thorp J., et al. Efficacy of flibanserin 100 mg qhs as a potential treatment for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in North American premenopausal women. Poster presented at the 12th Congress of the European Society of Sexual Medicine Congress. November 12–18, 2009 Leon, France. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borsini F., Evans K., Jason K., et al. Pharmacology of flibanserin. CNS Drug Rev. 2002;8(2):117–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2002.tb00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Invernizzi R.W., Sacchetti G., Parini S., et al. Flibanserin, a potential antidepressant drug, lowers 5-HT and raises dopamine and noradrenaline in the rat prefrontal cortex dialysate: role of 5-HT(1A) receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139(7):1281–1288. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balon R. Human sexuality: an intimate connection of psyche and soma—neglected area of psychosomatics? Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(2):69–72. doi: 10.1159/000190789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]