Abstract

The CCN (cyr61, ctgf, nov) proteins (CCN1–6) are an important family of matricellular regulatory factors involved in internal and external cell signaling. They are central to essential biological processes such as adhesion, proliferation, angiogenesis, tumorigenesis, wound healing, and modulation of the extracellular matrix. They possess a highly conserved modular structure with four distinct modules that interact with a wide range of regulatory proteins and ligands. However, at the structural level, little is known although their biological function(s) seems to require cooperation between individual modules. Here we present for the first time structural determinants of two of the CCN family members, CCN3 and CCN5 (expressed in Escherichia coli), using small angle x-ray scattering. The results provide a description of the overall molecular shape and possible general three-dimensional modular arrangement for CCN proteins. These data unequivocally provide insight of the nature of CCN protein(s) in solution and thus important insight into their structure-function relationships.

Keywords: Extracellular Matrix Proteins, Heparin-binding Protein, Protein Domains, Protein Structure, X-ray Scattering

Introduction

The CCN proteins are an important family of matricellular proteins that modulate cellular signaling and play a role in regulating critical cellular functions (for recent reviews, see Refs. 1 and 2). There are now six recognized members of the CCN family. The first three to be discovered, Cyr61 (cysteine-rich protein 61) (CCN1) (3), CTGF (connective tissue growth factor) (CCN2) (4), and Nov (nephroblastoma overexpressed gene) (CCN3) (5), gave rise to the CCN acronym (6). The remaining three members are the Wnt-inducible proteins Wisp1–3 (CCN4–6) (7). The standardized nomenclature (8) was necessary as many of the proteins had other names dependent on observed function; for example, CCN1 was previously known as Cyr61, CTGF-2, IGFBP10, and IGFBP-rP4 (8).

The CCN proteins are heavily involved in angiogenesis, chondrogenesis, proliferation, adhesion, wound healing, tumorigenesis, and cell survival (9–11). Although all of the CCN proteins have been shown to play some role in basic functions such as proliferation, adhesion, and migration, the role certain CCNs play in more complex biological functions, such as CCN1 and CCN2 in angiogenesis or CCN4 and CCN6 in cancer, is more pronounced (11–13). However, the biochemical basis, and importantly, the underlying protein-protein interactions that lead to these functions are not understood. CCN3, like all CCN proteins, is involved in many biological functions including cancer (14), regulation of angiogenesis (15), and cell adhesion (16). CCN5 was first identified in the WISP pathway and has been implicated heavily for its role in several types of cancers, most importantly breast (17) and colon (7) cancers, and for its role in bone turnover and chondrogenesis (18).

The complexity of CCN behavior is due to their large repertoire of ligands. These include the integrins, which are considered to be the “functional receptors of the CCN family”; the small cysteine knot growth factors (vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor (TGF), and bone morphogenic protein (BMP)2); extracellular matrix proteins (collagen, fibulin, and Notch); heparin sulfated proteoglycans; LDL receptor protein-1; and insulin growth factor (11, 12, 19) In some cases, the module that these receptors bind is known. VEGF isoforms bind to domains 3 and 4 of CCN2 (20) and domain 2 of CCN3 binds BMP2 (21). Aggrecan binds to the N terminus of CCN2 (either domain 1 or domain 2) (22), and domain 3 and domain 4 facilitate binding to heparin sulfated proteoglycans (23) and fibulin (16). For some functions, only a single domain is needed, but for others, multiple domains acting in concert are required (24). This raises questions about how the shape of the molecule influences its biological function.

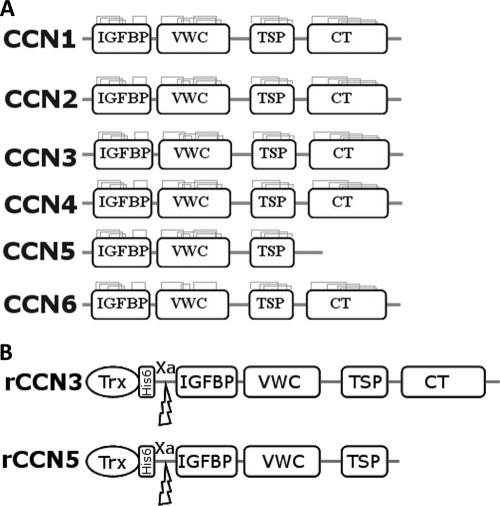

The CCN proteins, like many extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, are constructed from a series of distinct domains (25) that have evolved through exon shuffling (6, 26, 27). The building blocks that make up the CCN family are: 1) an insulin-like growth factor binding domain (IGFBP); 2) a von Willebrand type C repeat (VWC); 3) a thrombospondin type I repeat (TSP); and 4) a cysteine knot containing a carboxyl-terminal domain (CT) (6). A schematic diagram is shown in Fig. 1. These four domains have been shown to be discrete structural entities and can be produced as individual truncates that still possess biological activity (24). The CCN family is highly conserved at the primary structure level with ∼30–50% amino acid identity (and 40–60% similarity) (28, 29). CCN5 is an exception in that it lacks the CT domain but still maintains the first three highly conserved domains, and CCN6 lacks four normally conserved cysteine residues in the VWC domain. Protease-susceptible linkers separate the domains with the N- and C-terminal halves separated by a longer linker region that varies in both length and composition between the proteins. These linker regions can be cleaved by a range of matrix metalloproteases (MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, and MMP-13) (30) and proteases such as elastase and plasmin (30–32). Currently there is no structural information known about the CCN proteins. The high number of cysteines in each protein (∼10% by mass) makes obtaining pure material difficult (12), and previous attempts to purify these proteins have resulted in insoluble aggregates (33, 34). There has been some progress, with microgram quantities of active CCN2 produced in bacteria (35). Production of individual domains or truncated sections has been more successful (35–38), although it has not led to a greater understanding of the structure of the CCN proteins or their individual domains.

FIGURE 1.

A schematic diagram of the CCN family. A, the six members of the CCN family illustrating the four conserved domains. The conserved cysteine bonds are also shown in each domain with CCN6 lacking two of these in the VWC domain. CCN5 can also be seen to be lacking the CT domain (6). B, a schematic of the recombinant (r) constructs of CCN3 and CCN5 with an N-terminal Trx tag, an N-terminal hexa-histidine affinity tag, and a factor Xa cleavage site.

Although the structure of the individual domains can be hypothesized through homology modeling of related ECM domains (1), it does not yield any clues as to the overall shape of the molecule and any interdomain interactions that may occur. It has been hypothesized that the proteins exist as a globular bundle until positive or negative regulators act upon them to unfold and expose their active domains or cleave them at their protease-susceptible linkers into biologically active truncated fragments (9). Given the high degree of sequence identity between the proteins, it is likely that domain-domain interactions may be one of the factors that control the subtle differences in behavior and binding of these proteins (1, 2). In the case of CCN2, domain cooperativity has already been seen to influence ligand binding with domain 4 binding to VEGF121 and both domain 3 and domain 4 being required to bind the longer VEGF1165 (20). Experiments done by Kubota et al. (24) also demonstrated that certain biological effects were only seen when multiple domains were involved. Movement about linker regions has been seen to be important in other mosaic proteins (39), and the secondary structure, if any, of the linker regions can also have an effect on interdomain communication (40).

To begin to understand how structure can lead to function, we have expressed and purified CCN3 and CCN5 in high yields. We have elucidated their low resolution solution structures using small angle scattering to give us a first look at the hitherto unseen CCN protein family members.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning

The cDNA clones of CCN3 (IRATp970B0612D) and CCN5 (IRATp970H0284D) were obtained from imaGenes and cloned into the pET32-Xa/LIC vector at the ligation independent cloning site (Merck Biosciences), excluding the predicted signal sequence (residues 1–31 and 1–23, respectively). The pET32-rCCN vector was then transformed into Rosetta-Gami2 cells (Merck Biosciences) for expression.

Expression and Purification

Single colonies were used to inoculate 10 ml of LB supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and grown overnight at 37 °C. This was then used to inoculate 1 liter of LB supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 35 μg/ml chloramphenicol and was grown for ∼8 h at 37 °C before expression was induced with 0.2 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside and left for ∼16 h at 20 °C before cells were harvested through centrifugation. Cell pellets were frozen overnight at −20 °C before being resuspended in lysis buffer (25 mm Hepes, pH 7.3, 500 mm NaCl, 1 mm PMSF, EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablet (Roche Applied Science); 10% v/v Bugbuster; Benzonase; and rLysozyme (Merck Biosciences) and incubated for ∼20 min at room temperature before being lysed using a French press. Lysed cells were spun at 24,000 rpm for ∼30 min, and the inclusion bodies were collected. Inclusion bodies were resuspended in ∼20 ml solubilization buffer (25 mm Hepes, pH 7.3, 500 mm NaCl, 1 mm PMSF, 7.2 m urea) before being applied to a 1-ml His-Trap crude column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 25 mm Hepes, pH 7.3, 500 mm NaCl, 20 mm imidazole, and 7.2 m urea. The CCN proteins were eluted in a single step with elution buffer (as above, except 0.5 m imidazole). The partially purified CCN proteins were dripped slowly into ∼100 volumes of refolding buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8.2, 250 mm NaCl, 10 mm KCl, 0.05% PEG3350) and left at 4 °C for >24 h. The refolded CCN proteins were then subjected to a two-step purification using an ÄKTA Express (GE Healthcare) that involved an Ni2+ affinity column equilibrated with refolding buffer and eluted with an ascending imidazole gradient (0–500 mm) followed by gel filtration on a Superdex 75 column in 25 mm Tris, pH 8.2, 200 mm NaCl. Proteins were then concentrated for use in biophysical studies. The concentration was calculated using absorbance at 280 nm. Once concentrated, the purity was checked by SDS-PAGE and Western blot using anti-His antibodies targeting the N-terminal fused His tag. Samples were stored at 4 °C.

Circular Dichroism (CD)

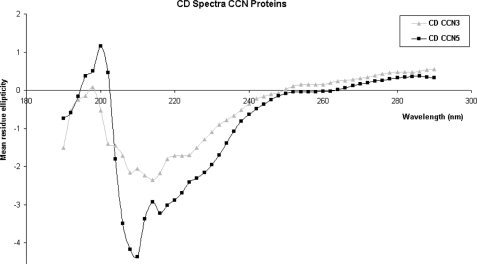

CD data were recorded on a Jasco-J600 spectropolarimeter at 25 °C from 190 to 290 nm with a 50 nm/min scanning speed using quartz cuvette with 5-mm path length. For both samples, eight runs were performed and averaged. A buffer blank (50 mm Tris, pH 8.2, 200 mm NaCl) was subtracted. An estimation of the secondary structure was performed by the program JFIT (41). CD data of CCN3 and CCN5 can be seen in Fig. 2.

FIGURE 2.

Circular dichroism data. CD spectra of CCN3 (gray triangles) and CCN5 (black squares) are shown. CD spectra were collected on a Jasco-J600 between 190 and 290 nm. Analysis in the program JFIT suggested that ∼50% of the protein was composed of β-strands, ∼40% consisted of random coil, and ∼10% consisted of α-helix. The large proportion of β-strand and coil is consistent with the homology modeling with the small proportion of α-helix likely from the Trx tag.

Dynamic Light Scattering

Dynamic light scattering analysis was performed on a Malvern Instruments machine at 20 °C. Protein concentration was ∼1 mg/ml in 25 mm Tris, pH 8.2, 200 mm NaCl, and samples were filtered through a 0.22-μm filter to remove any dust or particulates. For both CCN3 and CCN5, the samples were pure and monodispersed.

Small Angle X-ray Scattering Data Collection

Small angle x-ray scattering experiments were performed at beamline I22 at the Diamond Light Source (Didcot, Oxfordshire, UK) at 20 °C using a RAPID 2D detector. Scattering experiments using concentrations of 3.5 mg/ml for CCN3 and 5 and 3.5 mg/ml for CCN5 were performed using 300-s exposures, but no radiation damage was observed. A silver behenate standard was used for calibrating the q axis (42), and a 5 mg/ml lysozyme (mass 14.3kDa) solution in sample buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 8.2, 200 mm NaCl) was used as a molecular mass standard to calculate the mass of the CCN samples.

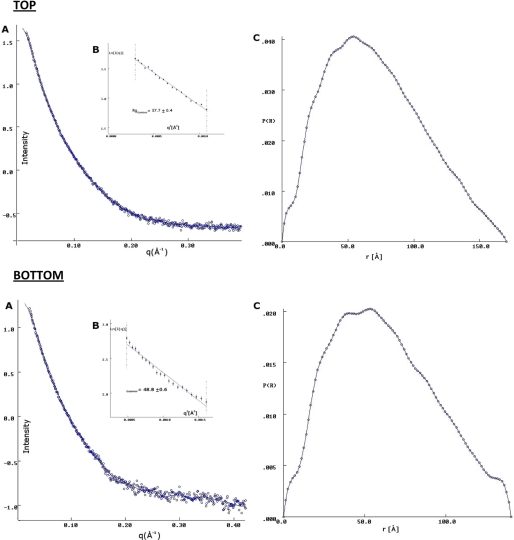

Data were analyzed and processed using the PRIMUS (43). Indirect Fourier transformation GNOM (44) was used to generate the pair distribution function of the samples and calculate the radius of gyration (Rg) and particle maximum dimension (Dmax). The scattering data for CCN3 and CCN5 can be seen in Fig. 3. Ab initio modeling was performed using the program DAMMIN (45). Twenty individual runs of DAMMIN were averaged by the program DAMAVER (46). Visualization of the molecular envelope and manual modeling of the homology models of the CCN domains were performed in PyMOL (62). A summary of the data collection details is provided in Table 1.

FIGURE 3.

Scattering curves for CCN3 and CCN5. Top, A, the scattering curve of CCN3 (blue circles). The fit to the ab initio data is shown in red and was calculated using the program DAMMIN (41). B, the radius of gyration (Rg) was calculated using the Guinier approximation (61) and was found to be 57.7 Å. C, the interatomic distance function (P(r)) gave a maximum dimension of 170 Å. These values were calculated in GNOM (44). Bottom, A, the scattering curve of CCN5 (blue circles). The fit to the ab initio data is shown in red and was calculated using the program DAMMIN (41). B, the radius of gyration (Rg) was calculated using the Guinier approximation (61) and was found to be 48.8 Å. C, the interatomic distance function (P(r)) gave a maximum dimension of 160 Å. These values were calculated in GNOM (44).

TABLE 1.

Small angle x-ray scattering data statistics

| CCN3 | CCN5 | |

|---|---|---|

| P(r) functiona | ||

| Rg (Å) | 57.7 | 48.8 |

| Dmax (Å) | 170 | 160 |

| Structural modeling | ||

| Discrepancyb (χ2) | 1.3 | 1.28 |

| NSD | 1.48 | 1.67 |

a The distance distribution function (P(r)) function from GNOM was used to calculate the radius of gyration (Rg) and the maximum dimension (DMax).

b The discrepancy (χ2) between experimental and ab initio data was calculated by the program DAMMIN. DAMAVER was used to average 20 models and gave the above value for normalized spatial discrepancy (NSD).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Expression and Purification

Both CCN3 and CCN5 proteins have been successfully expressed in the recombinant form and purified (>95% purity) to high concentration (47). In both cases, the proteins were constructed as recombinant protein in pET32 with an N-terminal thioredoxin (Trx) and hexa-histidine tag. The histidine tag was used for affinity purification, and the thioredoxin tag has been seen to help with the formation of disulfide bonds previously (35). In the case of CCN3, an ∼30-kDa breakdown product was observed before being removed using a high molecular weight cut-off filter. This fragment comprising the C-terminal region was also observed in preparations of CCN3 by Perbal et al. (16) and Thibout et al. (36). Despite the presence of the factor Xa cleavage site, both proteins were left with the Trx tag intact as upon cleavage, there were problems with protein precipitation at high concentrations.

Biophysical Experiments

Circular dichroism experiments of CCN3 and CCN5 gave curves compromising ∼50% β-strand and ∼40% random coil and are shown in Fig. 2. The small proportion of helical content (∼10%) is likely due to the presence of the attached Trx tag that is composed primarily of α-helices (Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID 1KEB) (48). This high ratio of β-strands and random coil is in agreement with homology modeling (1) and secondary structure prediction software. These suggested that domains 1–3 are composed entirely of β-strands and disulfide-stabilized random coil and that only the CT domain may contain a small proportion of α-helix. For CCN5 that lacks the CT domain, all of the observed helical content is likely due to the α-helices present in the Trx tag.

There have been suggestions that the CCN proteins may exist as dimers or higher order oligomers in solution due to the VWC and CT domains (10). The calculated mass (calculated from the distance distribution function (P(r) curve) gave a mass of 50.2 kDa for CCN3 and 38.1 kDa for CCN5, which is close to the calculated masses of the fusion proteins of 51.2 and 39.9 kDa, respectively. The monomeric state was also supported by the monodisperse nature of the peaks seen in the dynamic light scattering experiments, which were both >99% pure by dynamic light scattering analysis.

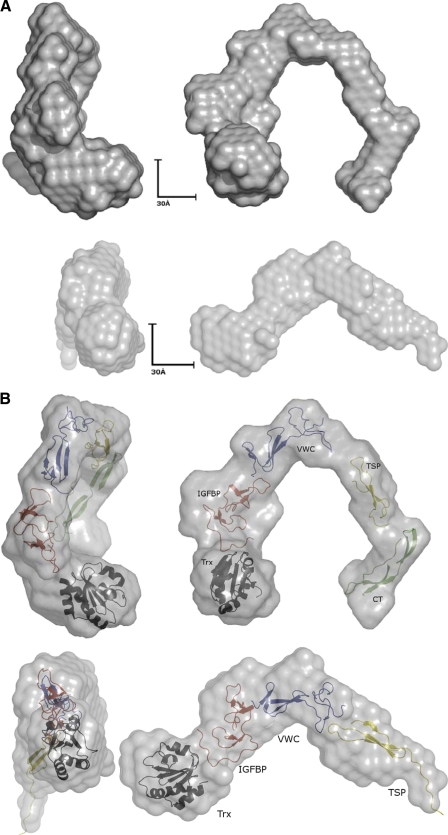

Ab Initio Modeling

Given the complete absence of structural data available for the CCN molecules, ab initio modeling was performed using the program DAMMIN (45) with 20 runs of DAMMIN (45) being averaged using the program DAMAVER (46). The resultant surface envelope models suggested that both proteins exist as extended, not globular, molecules in solution (Fig. 4A), differing from the globular hypothesis proposed by Perbal (9). This long extended flexible structure, although not immediately obvious as a stable protein, is in keeping with the known structural information about many of the other ECM multidomain proteins that exhibit similar long extended highly flexible structures (25). Fibronectin forms a long extended formation of small repeats (49), as does fibrillin (50), and all the current data on the related ECM modulator thrombospondin (51) also support the idea of a long extended molecule to allow for easy docking of ligands or multiple domains to interact with the same ligand simultaneously. The long linker region separating the N- and C-terminal halves of the molecule allows for a great deal of flexibility and could accommodate large domain movements for multiple domains to act in synergy with the binding ligands, as seen for domains 3 and 4 of CCN2, to simultaneously bind to VEGF165, as reported by Inoki et al. (20) or by Kubota et al. (24), using the four independent domains of CCN2. In addition to allowing flexible binding of multiple domains to ligands, the extended molecule allows access to the protease-susceptible sites that link the domains and may be why biologically active truncates are so prevalent among the CCN family (52, 53). These proteases include several matrix metalloproteases (MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, and MMP-13) that target the large linker region connecting the N- and C-terminal halves of the molecule, whereas other cellular proteases such as elastase and plasmin target the shorter linker between domains 1–2 and domains 3–4 (30–32).

FIGURE 4.

Model fitting to small angle x-ray scattering data. A, the ab initio models generated by DAMMIN (45) for CCN3 and CCN5. In both cases, they are long elongated molecules that are extended and may act as a scaffold for binding and coordinating ligand partners. B, the homology models generated of the individual domains of the CCN proteins modeled into the surface envelope of the small angle x-ray scattering model. The domains are colored with the Trx tag in black, the IGFBP domain in red, the VWC domain in blue, the TSP domain in yellow, and the CT domain in green. CCN5 lacks the CT domain. The figures were generated using PyMOL (62).

Although there is no direct structural information known about CCN proteins, it has been possible to form partial homology models for the individual domains (Fig. 4B) (1, 2). These models were built using homologous domains from other ECM proteins and maintain the same structural features and the same conserved motifs and are also in agreement with CD spectrum data that suggest that the CCN proteins are composed predominantly of β-sheet and random coil structure. The IGFBP domain is a flat domain that has a two-lobe arrangement with the active site cleft between the lobes and the N-terminal lobe of primarily random coil stabilized by a ladder-like arrangement of disulfide bonds and an anti-parallel β-sheet forming the C-terminal half. For CCN3 and CCN5, the IGFBP domain was modeled from the NMR structure of IGFBP4 (PDB 1DSP) (54). The VWC domain is related to fibronectin (55) and has two small β-sheets stabilized by disulfides at the N-terminal half and a C-terminal half stabilized by three disulfides without any major secondary structure elements. The NMR structure of the VWC domain from collagen IIa (PDB 1U5M) was used to generate the homology models (55). The TSP domain forms a three-stranded anti-parallel sheet with layers of cysteines, tryptophans, and arginines similar to thrombospondin (56), and the structure of the TSP domain from malaria TRAP protein (PDB 2BBX) was used for both CCN3 and CCN5 (57). Finally, the CT domain has a cysteine knot that is similar to that found in the growth factors such as VEGF, TGF, and BMPs (58). The CT domain in CCNs may have some structural differences outside of the cysteine knot as only a partial model of the CCN3 domain could be built using the structure of TGFβ-1 (PDB 1KLA) (59) as a template (1, 2).

With only partial homology models and an absence of structural data, we were unable to employ rigid body modeling programs such as SASREF (60); however, using molecular graphics programs, we were able to manually dock the modeled domains (1, 2) into the surface envelope produced by DAMMIN (45). In both cases, the ab initio surface envelope was able to comfortably accommodate the Trx tag and the functional domains for CCN3 and CCN5, aligning each domain so that the N and C termini were in the approximately correct orientation to link to the next domain. The available space between the domains also gave a large enough degree of freedom to comfortably accommodate the unstructured linker regions between each domain.

Given the high degree of homology (6) between CCN1–4 and CCN6, it is likely that this long extended flexible structure with each domain readily accessible for binding will hold true for every member of the CCN family. Although CCN5 lacks the CT domain that is responsible for many of the biological functions in CCN1–3 (9, 10, 12), CCN5 is still biologically active (13) and seems to share the same extended structure, suggesting that it is the interaction with other domains that is responsible for its biological activity and that subtle changes in the structure could be responsible for the observed activity.

Conclusion

Small angle x-ray scattering data have now given us our first insight into the structure of the full-length CCN proteins. It can now be hypothesized that they exist in the ECM as long extended scaffolds able to move and flex to allow multiple domains to bind a ligand, these domains working in concert to pass on messages throughout the cell. This first glimpse of the CCN structure when combined with higher resolution structural techniques may soon begin to answer some of the important questions about the molecular recognition of CCN proteins through their ligands. In addition, with further scattering experiments on CCN-ligand complexes, we may be able to observe the flexible nature of CCN binding.

This work was supported by a Royal Society Industry Fellowship and Cancer Research UK through a Biological Sciences Committee project grant award (C397/A12744) (to K. R. A.).

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- IGFBP

- insulin-like growth factor binding domain

- VWC

- von Willebrand type C repeat

- MMP

- metalloprotease

- Trx

- thioredoxin

- CT

- carboxyl-terminal domain.

REFERENCES

- 1. Holbourn K. P., Acharya K. R., Perbal B. (2008) Trends Biochem. Sci. 33, 461–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holbourn K. P., Perbal B., Acharya K. R. (2009) J. Cell Commun. Signal. 3, 25–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Brien T. P., Yang G. P., Sanders L., Lau L. F. (1990) Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 3569–3577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bradham D. M., Igarashi A., Potter R. L., Grotendorst G. R. (1991) J. Cell Biol. 114, 1285–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Joliot V., Martinerie C., Dambrine G., Plassiart G., Brisac M., Crochet J., Perbal B. (1992) Mol. Cell. Biol. 12, 10–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bork P. (1993) FEBS Lett. 327, 125–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pennica D., Swanson T. A., Welsh J. W., Roy M. A., Lawrence D. A., Lee J., Brush J., Taneyhill L. A., Deuel B., Lew M., Watanabe C., Cohen R. L., Melhem M. F., Finley G. G., Quirke P., Goddard A. D., Hillan K. J., Gurney A. L., Botstein D., Levine A. J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 14717–14722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brigstock D. R., Goldschmeding R., Katsube K. I., Lam S. C., Lau L. F., Lyons K., Naus C., Perbal B., Riser B., Takigawa M., Yeger H. (2003) Mol. Pathol. 56, 127–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perbal B. (2001) Mol. Pathol. 54, 57–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brigstock D. R. (1999) Endocr. Rev. 20, 189–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lau L. F., Lam S. C. (1999) Exp. Cell Res. 248, 44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen C. C., Lau L. F. (2009) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41, 771–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zuo G. W., Kohls C. D., He B. C., Chen L., Zhang W., Shi Q., Zhang B. Q., Kang Q., Luo J., Luo X., Wagner E. R., Kim S. H., Restegar F., Haydon R. C., Deng Z. L., Luu H. H., He T. C., Luo Q. (2010) Histol. Histopathol. 25, 795–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perbal B. (2006) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 587, 23–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lin C. G., Leu S. J., Chen N., Tebeau C. M., Lin S. X., Yeung C. Y., Lau L. F. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 24200–24208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perbal B., Martinerie C., Sainson R., Werner M., He B., Roizman B. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 869–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davies S. R., Watkins G., Mansel R. E., Jiang W. G. (2007) Ann. Surg. Oncol. 14, 1909–1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumar S., Hand A. T., Connor J. R., Dodds R. A., Ryan P. J., Trill J. J., Fisher S. M., Nuttall M. E., Lipshutz D. B., Zou C., Hwang S. M., Votta B. J., James I. E., Rieman D. J., Gowen M., Lee J. C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 17123–17131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perbal B. (2001) Bull. Cancer 88, 645–649 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Inoki I., Shiomi T., Hashimoto G., Enomoto H., Nakamura H., Makino K., Ikeda E., Takata S., Kobayashi K., Okada Y. (2002) FASEB J. 16, 219–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Minamizato T., Sakamoto K., Liu T., Kokubo H., Katsube K., Perbal B., Nakamura S., Yamaguchi A. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 354, 567–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aoyama E., Hattori T., Hoshijima M., Araki D., Nishida T., Kubota S., Takigawa M. (2009) Biochem. J. 420, 413–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adams J. C., Tucker R. P. (2000) Dev. Dyn. 218, 280–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kubota S., Kawaki H., Kondo S., Yosimichi G., Minato M., Nishida T., Hanagata H., Miyauchi A., Takigawa M. (2006) Biochimie 88, 1973–1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hohenester E., Engel J. (2002) Matrix Biol. 21, 115–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bornstein P. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 130, 503–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kireeva M. L., Mo F. E., Yang G. P., Lau L. F. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 1326–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brigstock D. R. (2003) J. Endocrinol. 178, 169–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Planque N., Long Li C., Saule S., Bleau A. M., Perbal B. (2006) J. Cell. Biochem. 99, 105–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hashimoto G., Inoki I., Fujii Y., Aoki T., Ikeda E., Okada Y. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 36288–36295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Winter P., Leoni P., Abraham D. (2008) Growth Factors 26, 80–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brigstock D. R., Steffen C. L., Kim G. Y., Vegunta R. K., Diehl J. R., Harding P. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 20275–20282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brigstock D. R. (2002) Angiogenesis 5, 153–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shimo T., Nakanishi T., Nishida T., Asano M., Kanyama M., Kuboki T., Tamatani T., Tezuka K., Takemura M., Matsumura T., Takigawa M. (1999) J. Biochem. 126, 137–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gygi D., Zumstein P., Grossenbacher D., Altwegg L., Lüscher T. F., Gehring H. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 311, 685–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thibout H., Martinerie C., Créminon C., Godeau F., Boudou P., Le Bouc Y., Laurent M. (2003) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ball D. K., Rachfal A. W., Kemper S. A., Brigstock D. R. (2003) J. Endocrinol. 176, R1–R7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tong Z. Y., Brigstock D. R. (2006) J. Endocrinol. 188, R1–R8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dobson C. M. (1990) Nature 348, 198–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Arai R., Wriggers W., Nishikawa Y., Nagamune T., Fujisawa T. (2004) Proteins 57, 829–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Altschuler E. L., Hud N. V., Mazrimas J. A., Rupp B. (1997) J. Pept Res. 50, 73–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang T. C., Toraya H., Blanton T. N., Wu Y. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 180–184 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Konarev P. V., Volkov V. V., Koch M. H. J., Svergun D. I. (2003) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 1277–1282 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Svergun D. I. (1991) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24, 485–492 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Svergun D. I. (1999) Biophys. J. 76, 2879–2886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Volkov V. V., Svergun D. I. (2003) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 860–864 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Holbourn K. P., Acharya K. R. (2011) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 407, 837–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rudresh, Jain R., Dani V., Mitra A., Srivastava S., Sarma S. P., Varadarajan R., Ramakumar S. (2002) Protein Eng. 15, 627–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Leahy D. J., Aukhil I., Erickson H. P. (1996) Cell 84, 155–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Downing A. K., Knott V., Werner J. M., Cardy C. M., Campbell I. D., Handford P. A. (1996) Cell 85, 597–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Carlson C. B., Lawler J., Mosher D. F. (2008) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 65, 672–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ayer-Lelievre C., Brigstock D., Lau L., Pennica D., Perbal B., Yeger H. (2001) Mol. Pathol 54, 105–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perbal B. (2004) Lancet 363, 62–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sitar T., Popowicz G. M., Siwanowicz I., Huber R., Holak T. A. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13028–13033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. O'Leary J. M., Hamilton J. M., Deane C. M., Valeyev N. V., Sandell L. J., Downing A. K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 53857–53866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tan K., Duquette M., Liu J. H., Dong Y., Zhang R., Joachimiak A., Lawler J., Wang J. H. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 159, 373–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tossavainen H., Pihlajamaa T., Huttunen T. K., Raulo E., Rauvala H., Permi P., Kilpeläinen I. (2006) Protein Sci. 15, 1760–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. McDonald N. Q., Hendrickson W. A. (1993) Cell 73, 421–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hinck A. P., Archer S. J., Qian S. W., Roberts A. B., Sporn M. B., Weatherbee J. A., Tsang M. L., Lucas R., Zhang B. L., Wenker J., Torchia D. A. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 8517–8534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Petoukhov M. V., Svergun D. I. (2005) Biophys. J. 89, 1237–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Guinier A. (1939) Ann. Phys. 12, 161–237 [Google Scholar]

- 62. DeLano W. L. (2010) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.3r1, Schrödinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]