Abstract

Dendritic cell (DC)-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN) is a type II transmembrane C-type lectin expressed on DCs such as myeloid DCs and monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs). Recently, we have reported that DC-SIGN interacts with carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) expressed on colorectal carcinoma cells. CEA is one of the most widely used tumor markers for gastrointestinal cancers such as colorectal cancer. On the other hand, other groups have reported that the level of Mac-2-binding protein (Mac-2BP) increases in patients with pancreatic, breast, and lung cancers, virus infections such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus, and autoimmune diseases. Here, we first identified Mac-2BP expressed on several colorectal carcinoma cell lines as a novel DC-SIGN ligand through affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry. Interestingly, we found that DC-SIGN selectively recognizes Mac-2BP derived from some colorectal carcinomas but not from the other ones. Furthermore, we found that the α1-3,4-fucose moieties of Le glycans expressed on DC-SIGN-binding Mac-2BP were important for recognition. DC-SIGN-dependent cellular interactions between immature MoDCs and colorectal carcinoma cells significantly inhibited MoDC functional maturation, suggesting that Mac-2BP may provide a tolerogenic microenvironment for colorectal carcinoma cells through DC-SIGN-dependent recognition. Importantly, Mac-2BP was detected as a predominant DC-SIGN ligand expressed on some primary colorectal cancer tissues from certain parts of patients in comparison with CEA from other parts, suggesting that DC-SIGN-binding Mac-2BP bearing tumor-associated Le glycans may become a novel potential colorectal cancer biomarker for some patients instead of CEA.

Keywords: Carbohydrate, Carbohydrate Binding Protein, Carbohydrate Function, Colon Cancer, Dendritic Cell, Lectin, Tumor Marker

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs)4 play a critical role in initiating adaptive immunity by uptaking foreign antigens at the periphery, undergoing maturation during migration to lymph nodes and presenting antigen-derived peptides to naïve T cells (1, 2). For effective recognition of antigens, DCs exploit a wide range of pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors and C-type lectins (3–5). DC-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN; CD209) is a type II transmembrane C-type lectin expressed on myeloid DCs in the dermis, mucosae, lymph nodes, and monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs) (6, 7). DC-SIGN binds to “self” glycan ligands found on human cells and to “foreign” glycans of bacterial or parasitic pathogens, and specifically recognizes glycoconjugates containing mannose (Man), fucose (Fuc), and nonsialylated Lewis (Le)a/Leb epitope structures in a Ca2+-dependent manner (8). Through recognition of these glycans, DC-SIGN functions as an adhesion receptor and mediates the binding and internalization of foreign pathogens such as viruses (human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus), yeasts, bacteria (Mycobacterium tuberculosis), and parasites (3).

Recently, we and another group (9, 10) found that DC-SIGN recognizes colorectal carcinoma cells through carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). DC-SIGN-binding CEA contained tumor-associated Le glycans, which were important for cellular interactions between DCs and colorectal carcinoma cells in situ. It is evident that the expression of CEA is limited and can be detected only in cancer and embryonic tissues. This glycoprotein is one of the most widely used tumor markers for gastrointestinal cancers such as colorectal carcinomas. However, its sensitivity and specificity are not high, particularly for early stages of the disease such as Dukes A or B stages. Based on our studies, we hypothesized that DC-SIGN may also be involved in the recognition of other glycoproteins, as novel potential biomarkers, expressed on colorectal cancers.

In this study, we first identified Mac-2-binding protein (Mac-2BP) expressed on colorectal carcinoma cells as a novel DC-SIGN ligand through affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry. Mac-2BP, also known as 90K or galectin-3BP, is a secretory glycoprotein expressed on various normal epithelial cells and in human bodily fluids. It has been reported that the level of Mac-2BP increases in patients with pancreatic, breast, and lung cancer, virus infections such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and hepatitis C, and autoimmune diseases (11). However, most of the immunological significance of Mac-2BP on colorectal carcinomas remains unknown.

In addition, we found that DC-SIGN-dependent cellular interactions between immature MoDCs and colorectal carcinoma cells mainly expressing Mac-2BP were able to significantly inhibit LPS-induced MoDC functional maturation. Furthermore, we also detected Mac-2BP as a predominant DC-SIGN ligand expressed on some primary colorectal cancer tissues from certain parts of patients in comparison with CEA from the other parts. Therefore, we suggest that Mac-2BP carrying fucosylated glycans may become a novel potential colorectal cancer biomarker for some CEA-low or -negative colorectal cancer patients, and the novel function of DC-SIGN may, at least in part, underlie for its potential use as a novel diagnostic sensor for some colorectal cancer patients through recognition of CEA and Mac-2BP.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

Recombinant human DC-SIGN-human IgG-Fc fusion protein (rhDC-SIGN-Fc), anti-human DC-SIGN mAb, and anti-Mac-2BP polyclonal antibody (pAb) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Anti-Mac-2BP mAb was from Bender Medsystems (Burlingame, CA). Anti-Lea, Leb, and CEA mAbs were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Anti-human CD83 and CD86 mAbs were from BD Biosciences. Alexa Fluor 488- or 546-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen. HRP-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody and Ultrapure lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli 0111:B4 were from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-human DC-SIGN pAb (C-20) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). All chemicals for gel electrophoresis and Western blotting were purchased from Nacalai Tesque, ATTO Corp. (Tokyo, Japan), Bio-Rad, Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA), or Invitrogen.

Cell Lines, Cell Culture, and Immature MoDCs and Maturation of Immature MoDCs

Human colon tumor cell lines COLO205 and SW1116 and human hepatoma cell line HLF were cultured as described previously (10). All of the cell lines were obtained from ATCC. DC-SIGN-expressing HLF cells (HLF-DC-SIGN) were generated by transfection of the pcDNA3-DC-SIGN plasmid (10) with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), and then selection was performed in complete medium containing 1 mg/ml G418 (Invitrogen) for stable transfectants. Isolation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy donors, positive selection of CD14+ cells, induction of immature MoDCs, and maturation of MoDCs were conducted as described previously (10) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. DC maturation was confirmed by expression of CD83, a DC-specific maturation marker, and CD86, a costimulatory molecule, on mature but not immature DCs.

Cellular Adhesion Assay

HLF-DC-SIGN or HLF cells were incubated into confluent culture at 37 °C in 96-well plates and then COLO205 cells, which had been prelabeled with the green fluorescent dye calcein-AM (Invitrogen), were added onto the wells and incubated for 1 h. After unbound cells were removed with wash buffer (0.5% BSA, 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), and 1 mm CaCl2), cells on the plates were lysed with lysis buffer (20 mm Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), and 0.1% SDS) and analyzed by fluorometry at 488 nm. Population of adhered COLO205 cells was calculated as the percentage of maximal binding, which was determined by the lysed total amount of added calcein-AM-labeled cells (100% adhesions).

ELISA Analysis

For analysis of DC-SIGN binding to proteins secreted by HLF, COLO205, or SW1116 cells, culture supernatants were mixed with coating buffer (Na2CO3 buffer, pH 9.6) and then coated onto NUNC maxisorp 96-well plates (Nalge Nunc) overnight at 4 °C. Mannan was used as a positive control. Then, the plates were blocked with 3% BSA in coating buffer for 1 h at room temperature, washed with TBS (pH 7.6) containing 0.05% Tween 20, and then incubated with 0.4 μg/ml rhDC-SIGN-FLAG in 1% BSA in TBS (pH 7.6) containing 5 mm CaCl2 for 1 h at room temperature. After the plates had been washed, HRP-conjugated anti-FLAG mAb was added, followed by incubation for 1 h.

For analysis of DC-SIGN binding to Mac-2BP secreted by human hepatoma and colorectal carcinoma cell lines, 1 μg/ml anti-Mac-2BP pAbs were precoated onto 96-well plates overnight at 4 °C. After blocking, culture supernatants of HepG2, HLF, COLO205, LS180, or SW1116 cells were added, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature. DC-SIGN binding was assayed using rhDC-SIGN-FLAG, as described above.

For quantitative kinetic data of association between DC-SIGN and Mac-2BP, 5 ng/well of Mac-2BP captured onto plates were reacted for 2 h with different concentrations (0.063–8.000 nm) of rhDC-SIGN-FLAG in the presence of 5 mm CaCl2. Quantitative kinetic data (Kd app and Bmax) were calculated based on the amounts of total and unbound rhDC-SIGN-FLAG using a nonlinear regression model by GraphPad Prism software (version 4.0c). DC-SIGN was regarded as a tetramer.

For determination of the glycan profile of COLO205-derived Mac-2BP, anti-Mac-2BP pAb was precoated onto 96-well plates overnight at 4 °C. After blocking, culture supernatants of HLF or COLO205 cells were added, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature. Then the captured Mac-2BP was incubated with biotin-conjugated plant lectins (phytohemeagglutinin (PHA)-L4, Lycopersicon esculentum agglutinin, and Aleuria aurantia agglutinin (AAL)), followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated avidin. After development, binding was quantitated by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm using a Multilabel Counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. All experiments were performed in triplicate and were repeated a minimum of three times.

Preparation of Membrane Fractions, Affinity Chromatography, and Mass Spectrometry

Affinity sepharoses were prepared using Seize X Protein G Immunoprecipitation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). According to the manufacturer's instructions, rhDC-SIGN-Fc and hIgG-Fc proteins were immobilized to Protein G-Sepharose using the cross-linker disuccinimidyl suberate. Cells were homogenized in homogenization buffer (10 mm Tris/HCl (pH 7.6), 0.5 mm MgCl2, and protease inhibitor mixture), and then tonicity was restored into 150 mm NaCl. The homogenate was centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris and nuclei. The supernatant was supplemented with EDTA to 5 mm and then centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 45 min at 4 °C. The resulting total membrane pellet was solubilized with lysis buffer (150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor mixture) for 60 min at 4 °C and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 60 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was saved as the solubilized COLO205 membrane proteins and was applied to a rhDC-SIGN-Fc or hIgG-Fc affinity column. After the column had been washed with TBS buffer (pH 7.5) containing 5 mm CaCl2 and 0.1% Triton X-100, the proteins bound to the column were eluted with TBS buffer (pH 7.5) containing 10 mm EDTA and 0.1% Triton X-100. The EDTA-eluted fractions were buffer-exchanged, applied again to the same column and then eluted with TBS buffer (pH 7.5) containing 50 mm Man. The secondly eluted proteins were resolved on a 5–20% Tris/HCl gradient gel (ATTO Corporation) and then stained with a silver staining kit (Wako Pure Chemical Industries). Bands were excised from the gel and subjected to in-gel digestion. The peptides released from the gel were subjected to LC/MS/MS with a linear ion trap mass spectrometer (LTQ, Thermo Fisher Scientific) interfaced on-line with a nano HPLC (Paradigm, Michrom BioResources, Auburn, CA). The eluents consisted of H2O containing 2% CH3CN and 0.1% formic acid (Pump A), and 90% CH3CN and 0.1% formic acid (Pump B), and the peptides were eluted with a linear gradient of 5–80% from Pump B. Data-dependent MS/MS acquisition was performed for the most intense ions as precursors. Proteins were identified by searching the Swiss-Prot Homo sapiens and NCBInr database (human) using the Mascot search engine (Matrixscience, London, UK) and Bioworks search engine (Thermo Fisher Scientific), respectively.

Ligand Precipitation, Immunoprecipitation, and Immunoblotting

Solubilized membrane proteins from HLF, COLO205, and SW1116 cells were prepared as described above, and used as ligand precipitation, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblot samples. To identify the proteins carrying DC-SIGN carbohydrate ligands on colorectal carcinomas, precipitation was performed using rhDC-SIGN-Fc- or rhIgG-Fc-Protein G beads, and the bound proteins were eluted with EDTA as immunoblot samples. The samples were resolved on 5–20% gradient SDS-PAGE gels (ATTO Corp.) and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, followed by immunoblot detection with specific antibodies. For visualization, a SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-goat IgG. The amounts of SDS-PAGE loading proteins from HLF, COLO205, and SW1116 cells were adjusted on the basis of cell numbers, and we confirmed by Bradford method that whole membrane lysates contained 15–20 μg/lane and culture supernatant contained 27–32 μg/lane of comparable proteins (data not shown).

Glycan Digestion Assay

For peptide-N-glycosidase (PNGase) F treatment, membrane proteins prepared from COLO205 cells, as described above, were adjusted to 10 mm EDTA, 0.1% SDS, and 0.1% Nonidet P-40 and then incubated overnight with or without PNGase F at 37 °C. After replacement in Hepes buffer (pH 7.5)-0.15 m NaCl by ultrafiltration, DC-SIGN ligands were precipitated with rhDC-SIGN-Fc, followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-Mac-2BP pAb. For α1-3,4-fucosidase treatment, a membrane pellet of COLO205 cells prepared as described above was suspended in 20 mm KH2PO4 (pH 5.0) buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40, followed by incubation overnight with or without α1-3,4-fucosidase at 37 °C, and then ligand precipitation with rhDC-SIGN-Fc, anti-Lea or -Leb mAb, SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting with anti-Mac-2BP pAb.

MoDC Functional Maturation

To determine the effect of a MoDC-COLO205-cocultured supernatant on LPS-induced functional maturation of MoDCs, immature MoDCs were incubated in a MoDC-cultured or MoDC-SW1116-cocultured supernatant for 3 days in the presence of IL-4 (500 units/ml), GM-CSF (800 units/ml), and LPS (1 ng/ml). Supernatant of MoDC, which cultured in the presence of anti-DC-SIGN pAb, was used as a control. Cultures were replenished with fresh supernatant on the second day. The effect on MoDC functional maturation was determined by cell-surface expression of CD83, a DC-specific maturation marker, and CD86, a costimulatory molecule on mature DCs, using FACS CaliburTM, and the mean fluorescent intensity was calculated with CELLQUEST softwareTM (BD Biosciences). All experiments were performed in triplicate and were repeated a minimum of three times.

Histochemistry

Clinical colorectal cancer tissue specimens were purchased from SuperBioChips Laboratories (Seoul, Korea), or obtained from Shiga University of Medical Science with informed consent. This project was approved by the ethics committee of Shiga University of Medical Science. Following deparaffinization and hydration of paraffin-embedded tissue sections, antigen retrieval was performed by steaming in citrate buffer (pH 6.0). After blocking with 1% BSA, the slides were incubated with 1 μg/ml of anti-Mac-2BP pAb followed by Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated secondary Ab (for anti-Mac-2BP staining), anti-CEA mAb (1:50) followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary Ab (for anti-CEA staining), and/or 1 μg/ml of allophycocyanin-conjugated rhDC-SIGN-FLAG (for direct rhDC-SIGN staining, donor 1) or rhDC-SIGN-FLAG followed by anti-FLAG mAb and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary Ab (for indirect rhDC-SIGN staining, donor 2), and then washed and mounted. To observe the expression of DC-SIGN ligands on COLO205 cells, cells were stained with 1 μg/ml of rhDC-SIGN-allophycocyanin and anti-Mac-2BP pAb, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary Ab in the presence of CaCl2 or EDTA. To investigate cellular interactions between immature MoDCs and COLO205 cells, cells were coincubated for 1 h at 37 °C and then stained with 1 μg/ml of anti-DC-SIGN mAb and anti-Mac-2BP pAb or anti-Leb mAb, followed by Alexa Fluor 488- and 546-conjugated secondary Abs. The cellular interactions were visualized by laser confocal microscopy.

Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of data obtained in three experiments performed in triplicate. Statistical significance was determined by means of Student's t test.

RESULTS

DC-SIGN-mediated Cellular Adhesions and Mac-2BP Identified as a Novel DC-SIGN Ligand on Colorectal Carcinoma Cells

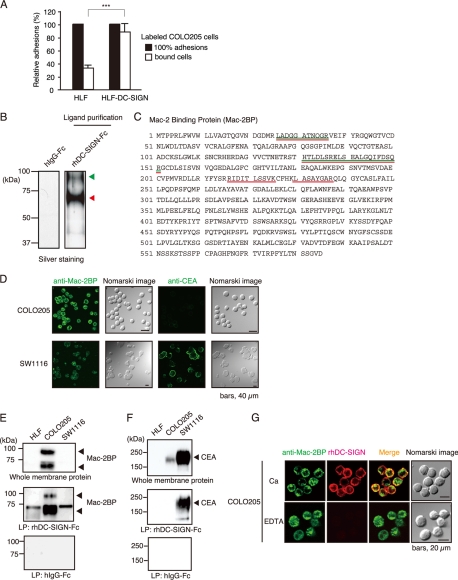

To determine whether or not DC-SIGN-expressing cells interact with human colorectal carcinoma cells, we coincubated either human hepatoma HLF cells or DC-SIGN-expressing HLF (HLF-DC-SIGN) cells with COLO205 cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, COLO205 cells significantly bound to HLF-DC-SIGN cells compared with control HLF cells, indicating that DC-SIGN is sufficiently involved in the cellular adhesions through interaction with DC-SIGN ligands expressed on COLO205 cells.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of Mac-2BP expressed on colorectal carcinomas as a novel ligand for DC-SIGN. A, DC-SIGN-mediated cellular adhesions with COLO205 cells. HLF or HLF-DC-SIGN cells bound with calcein-AM-labeled COLO205 cells were lysed and analyzed by fluorometry at 488 nm. The relative adhesions are shown. Error bars indicate S.D. (n = 3). B, purification of DC-SIGN ligands expressed on COLO205 cells. DC-SIGN ligands were purified with a DC-SIGN affinity column and then detected by silver staining. The arrowheads indicate the elution positions of the purified DC-SIGN ligands. The molecular mass markers are shown on the left. C, identification of DC-SIGN novel ligands by MS. The purified DC-SIGN ligand bands were analyzed by MS. The identified peptides are shown in green (upper band) or red (lower band), respectively. D, confocal microscopic images of the expressions of Mac-2BP and CEA on COLO205 and SW1116 cells. Cells were stained with anti-Mac-2BP pAb or anti-CEA mAb (green). Nomarski images are shown on the right. E and F, ligand precipitation (LP) analysis of the interaction of DC-SIGN with CEA or Mac-2BP. Solubilized membrane proteins of HLF, COLO205, and SW1116 cells were precipitated with rhDC-SIGN-Fc or hIgG-Fc, and then EDTA-eluted DC-SIGN ligands were detected by immunoblotting using anti-Mac-2BP pAb (E) or anti-CEA mAb (F). G, confocal microscopic images of the interactions between DC-SIGN and Mac-2BP on COLO205 cells. The cells were costained with anti-Mac-2BP pAb (green) and rhDC-SIGN-allophycocyanin (red) in the presence of CaCl2 or EDTA.

To completely isolate DC-SIGN ligands expressed on COLO205, the ligand glycoproteins from solubilized membrane fractions were purified by an affinity column of recombinant human DC-SIGN-Fc (rhDC-SIGN-Fc) and then analyzed by nano-LC/MS/MS, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The two major silver-stained bands, which were independent of the Fc portion of the DC-SIGN-Fc chimeric protein, indicated by the arrows (Fig. 1B) from rhDC-SIGN-Fc column were identified as matured and degraded Mac-2BP, respectively (Fig. 1C).

On the other hand, we previously identified CEA as the main DC-SIGN ligand expressed on SW1116 cells, another human colorectal carcinoma cell line. Therefore, we compared the expression levels of Mac-2BP and CEA between COLO205 and SW1116 cells by confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 1D, the cell-surface expression of Mac-2BP was markedly higher on COLO205 than SW1116 cells. In contrast, CEA could hardly be detected on COLO205 cells compared with its abundant expression on SW1116 cells.

Next, to confirm the interaction of DC-SIGN with Mac-2BP in vitro, DC-SIGN ligands purified from COLO205, SW1116, and human hepatoma HLF cells were immunoblotted with anti-Mac-2BP pAb (Fig. 1E) or anti-CEA mAb (Fig. 1F). The results showed that COLO205-derived Mac-2BP, but not HLF or SW1116-derived Mac-2BP, apparently interacted with rhDC-SIGN (Fig. 1E). In contrast, we observed high-level expression of CEA on SW1116 cells and its distinct association with rhDC-SIGN (Fig. 1F), whereas we could not detect any association of COLO205-derived CEA with rhDC-SIGN. Confocal microscopy also showed that Mac-2BP (green) was substantially colocalized with allophycocyanin-fluoresceinated rhDC-SIGN (red) on COLO205 cells in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Fig. 1G). These findings indicated that Mac-2BP is a novel DC-SIGN ligand expressed on colorectal carcinoma cells and that DC-SIGN selectively interacts with Mac-2BP expressed on particular carcinoma cells as opposed to CEA.

DC-SIGN Binds to Mac-2BP Secreted by Several Colorectal Carcinoma Cell Lines

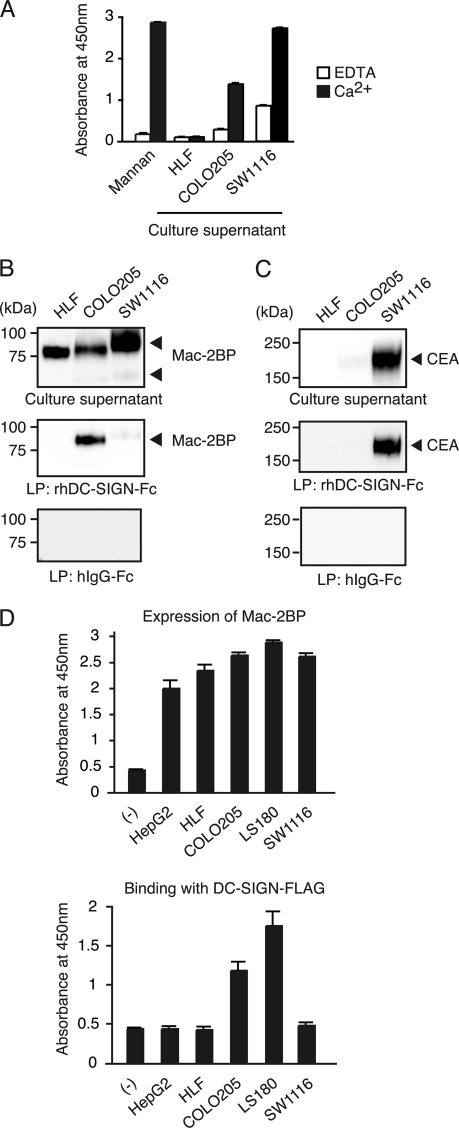

Mac-2BP and CEA were known originally as secretory proteins. Therefore, we examined whether or not DC-SIGN ligands existed in COLO205-, SW1116-, or HLF-cultured supernatants. As shown in Fig. 2A, ELISA analysis revealed that DC-SIGN ligand glycoproteins could be detected in a Ca2+-dependent manner in both COLO205- and SW1116-cultured supernatants, but not in a HLF-cultured supernatant.

FIGURE 2.

Culture supernatants derived from colorectal carcinoma cells contain secreted Mac-2BP that can be recognized by DC-SIGN. A, culture supernatant of colorectal carcinoma cells contain DC-SIGN-ligands. Total culture supernatant proteins from HLF, COLO205, and SW1116 cells, coated onto plates, were detected with rhDC-SIGN in the presence of 5 mm CaCl2 or EDTA. Mannan was used as a positive control for DC-SIGN binding. Error bars indicate S.D. (n = 3). B and C, DC-SIGN interacts selectively with COLO205-derived Mac-2BP or SW1116-derived CEA contained in culture supernatants. A total culture supernatant and purified DC-SIGN ligands from HLF, COLO205, or SW1116 cells were immunoblotted with anti-Mac-2BP pAb or anti-CEA mAb. D, colorectal carcinoma cells secrete Mac-2BP that can be recognized by DC-SIGN. Mac-2BPs from human hepatoma HepG2 and HLF and colorectal carcinoma COLO205, LS180, and SW1116 cells were captured with anti-Mac-2BP pAb and then detected with anti-Mac-2BP mAb (upper panel) or with rhDC-SIGN-FLAG (lower panel), respectively. Error bars indicate S.D. (n = 3).

Next, to verify that DC-SIGN interacts with secreted CEA and Mac-2BP, purified DC-SIGN ligands from HLF-, COLO205-, and SW1116-cultured supernatants were immunoblotted with anti-Mac-2BP pAb and anti-CEA mAb, respectively. Interestingly, only Mac-2BP secreted by COLO205 cells, but not by HLF or SW1116 cells, interacted with rhDC-SIGN (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, CEA, which can interact with DC-SIGN, was only observed in the SW1116-cultured supernatant (Fig. 2C). Moreover, we investigated the interaction of DC-SIGN with Mac-2BP secreted by several other human hepatoma and colorectal carcinoma cell lines (Fig. 2D). The ELISA data showed that the human hepatoma HepG2 and HLF, and human colorectal carcinoma COLO205, LS180, and SW1116 cell lines all apparently expressed Mac-2BP (Fig. 2D, upper panel); however, only the COLO205- and LS180-derived Mac-2BP had the ability to interact with rhDC-SIGN (lower panel), indicating that parts of colorectal carcinomas can secrete DC-SIGN-recognizing Mac-2BP. These results also suggest that distinct glycoforms of Mac-2BP exist in different colorectal carcinomas.

DC-SIGN Binds to Mac-2BP from Colorectal Carcinoma Cells in Ca2+-dependent and Dose-dependent Manners

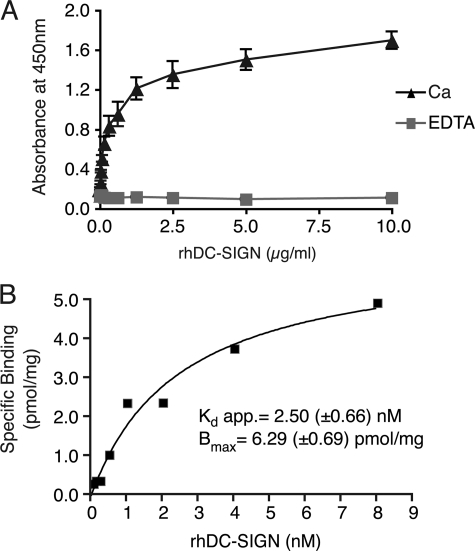

To quantitatively characterize the direct association between DC-SIGN and COLO205-derived Mac-2BP, we performed ELISA experiments. As shown in Fig. 3A, the interactions were monitored as the changes in the ELISA responses, and the Ca2+ chelator EDTA completely blocked the interactions, suggesting that DC-SIGN directly binds to glycans on Mac-2BP in a dose-dependent manner, and the interaction occurs in a Ca2+-dependent manner and the CRD of DC-SIGN mediates the binding.

FIGURE 3.

Biochemical analysis of the interaction between DC-SIGN and Mac-2BP. A, DC-SIGN-dependent interaction with COLO205-derived Mac-2BP. Mac-2BP, captured with anti-Mac-2BP pAb onto plates, was detected with different concentrations of rhDC-SIGN-FLAG in the presence of 5 mm CaCl2 or EDTA. Error bars indicate S.D. (n = 3). B, quantitative kinetic analysis for association between DC-SIGN and Mac-2BP. The apparent (app.) dissociation constant (Kd app.) and Bmax were calculated based on the amounts of total and unbound rhDC-SIGN-FLAG using a nonlinear regression model.

Moreover, their affinity level was shown to be extremely high when the apparent dissociation constant (Kd app = 2.50 (±0.66)) was calculated by fitting a curve using nonlinear regression model (Fig. 3B). These results suggest the potential physiological interaction between DC-SIGN and Mac-2BP in the colon microenvironment.

DC-SIGN Recognizes Fucose Residues of Le N-Glycans on Mac-2BP from Colorectal Carcinoma Cells

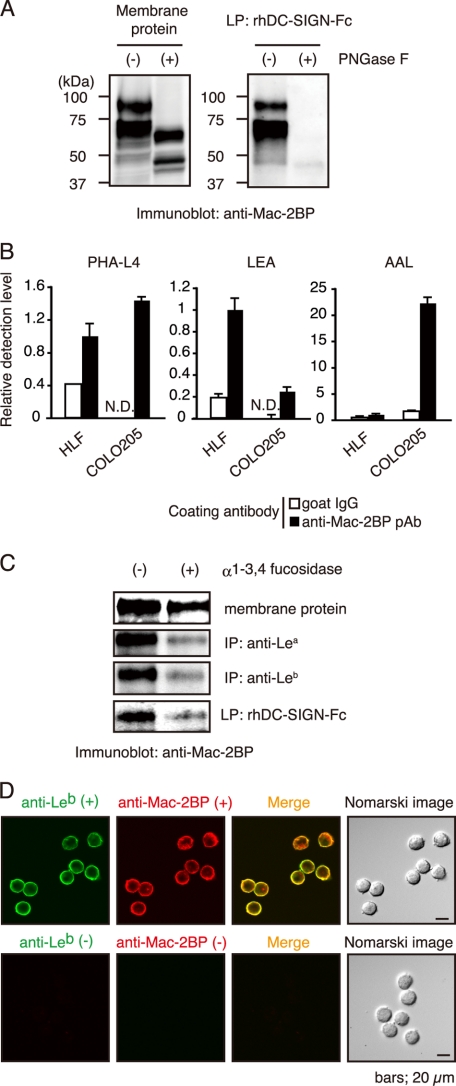

To determine whether or not interaction of Mac-2BP with DC-SIGN is N-glycan-dependent, Mac-2BP purified from COLO205 cells was treated with PNGase F and then precipitated with rhDC-SIGN. Fig. 4A shows that the Mac-2BP band shifted from 90 to 65 kDa on PNGase F treatment and that the PNGase F-treated form had completely lost the ability to bind rhDC-SIGN, indicating that the N-glycans on Mac-2BP mediate the interaction with DC-SIGN.

FIGURE 4.

Fucose residues of colorectal carcinoma-associated Lewis N-glycans expressed on COLO205-derived Mac-2BP are essential for DC-SIGN binding. A, N-glycans of COLO205-derived Mac-2BP are essential for DC-SIGN binding. COLO205 membrane proteins were incubated with or without PNGase F, and then total membrane proteins (left) and subsequently purified DC-SIGN-ligands (right) were immunoblotted with anti-Mac-2BP pAb. B, determination for the Mac-2BP glycan profile by ELISA. COLO205-derived Mac-2BP glycoproteins captured with pre-coated anti-Mac-2BP pAb were detected with biotinylated plant lectin PHA-L4 (left), Lycopersicon esculentum agglutinin (LEA, middle), or AAL (right). Goat IgG was used as an isotype control for anti-Mac-2BP capture pAb. Detection levels for HLF-derived Mac-2BP were arbitrarily set at 1. Error bars indicate S.D. (n = 3). C, DC-SIGN recognizes the fucose residues of Le glycans expressed on COLO205-derived Mac-2BP. COLO205 membrane proteins were incubated with or without α1-3,4-fucosidase and then precipitated with rhDC-SIGN-Fc, anti-Lea or -Leb mAb, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Mac-2BP pAb. IP, immunoprecipitation. D, confocal microscopic image of Leb expression on COLO205-derived Mac-2BP. The cells were costained with anti-Leb mAb (green) and anti-Mac-2BP pAb (red). Staining without primary Abs was performed as a negative control. LP, ligand precipitation.

We next examined whether or not DC-SIGN-binding Mac-2BP expresses characteristic glycans by ELISA involving commonly used plant lectins (Fig. 4B). Well-coated Mac-2BP was incubated with three plant lectins, PHA-L4, Lycopersicon esculentum agglutinin, and AAL, respectively. Lycopersicon esculentum agglutinin, which predominantly recognizes polylactosamine glycans, exhibited a high degree of binding to HLF-derived Mac-2BP and a low degree of binding to COLO205-derived Mac-2BP. Whereas PHA-L4, which recognizes β1-6 branched GlcNAc glycans, exhibited almost the same degree of binding to HLF- and COLO205-derived Mac-2BPs, suggesting that β1-6 branched GlcNAc glycans are not the direct moieties for DC-SIGN binding. Interestingly, fucose-binding AAL lectin exhibited much stronger affinity with COLO205-derived than HLF-derived Mac-2BP.

AAL lectin exhibits a high affinity for α-fucosyl residues in the cores of N-linked glycans and Le glycans such as Lea, Leb, Lex, Ley, sialyl-Lex, and sialyl-Lex. Because DC-SIGN exhibits the highest affinity to Le glycans, but not to sialylated Le glycans, we hypothesized that fucose residues on Le glycans may directly mediate the interaction between DC-SIGN and COLO205-derived Mac-2BP. To prove this, we treated Mac-2BP with α1-3,4-fucosidase, an enzyme that specifically cleaves α1-3,4-bound fucose of Lea, Leb, Lex, and Ley. As shown in Fig. 4C, the defucosylated Mac-2BP had almost completely lost the ability to interact with DC-SIGN. Confocal microscopy also showed that Mac-2BP (red) significantly expresses Leb glycans (green) on COLO205 cells (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that DC-SIGN is selective in its recognition of specific types of fucosylated N-glycans and that these N-glycans expressed on DC-SIGN-binding Mac-2BP are important for the interaction.

DC-SIGN Mediates Cellular Adhesion between Immature MoDCs and COLO205 Cells

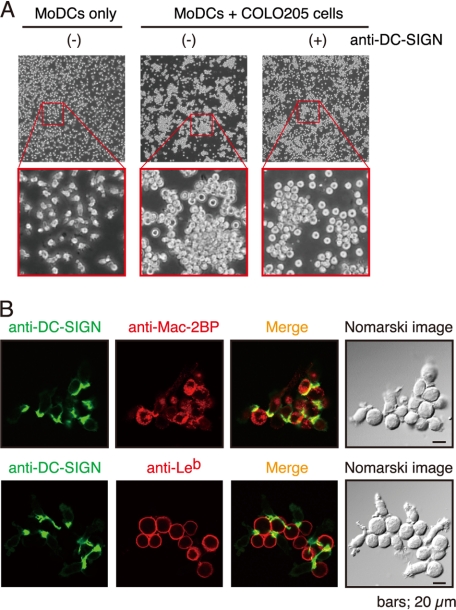

Next, to determine whether or not immature DCs interact with COLO205 cells through DC-SIGN, we prepared MoDCs from human peripheral blood monocytes and cocultured them with COLO205 cells. As shown in Fig. 5A, MoDCs were found to stably adhere to COLO205 cells and to form large agglutinations when they were cocultured (middle), compared with a MoDC culture control (left). The addition of anti-DC-SIGN pAb partially blocked the MoDC-COLO205 interactions and agglutinations (right), indicating that DC-SIGN mediated the interactions and agglutinations. Furthermore, confocal microscopy demonstrated that immature MoDCs expressed a remarkable level of DC-SIGN (green) at the points of contact with COLO205 cells expressing both Mac-2BP (upper) and Leb (lower, red) (Fig. 5B). These results, also considering the results of Fig. 4, C and D, suggest that Mac-2BP carrying Leb glycans is involved in the association between MoDCs and colorectal cancer cells in situ.

FIGURE 5.

DC-SIGN mediates interaction between MoDCs and COLO205 cells. A, DC-SIGN-dependent cellular adhesions between MoDCs and COLO205 cells. MoDCs only (left) or MoDCs plus COLO205 cells in the presence (right) or absence (middle) of anti-human DC-SIGN pAb were cultured and visualized by phase-contrast microscopy. B, confocal microscopic images of MoDC-COLO205 cellular interactions mediated by DC-SIGN and Mac-2BP. MoDCs were cocultured with COLO205 cells. After fixation, cells were stained with anti-human DC-SIGN mAb (green) and anti-Mac-BP pAb or anti-Leb mAb (red).

DC-SIGN-mediated Cellular Adhesion between Immature MoDCs and COLO205 Cells Attenuates MoDC Maturation

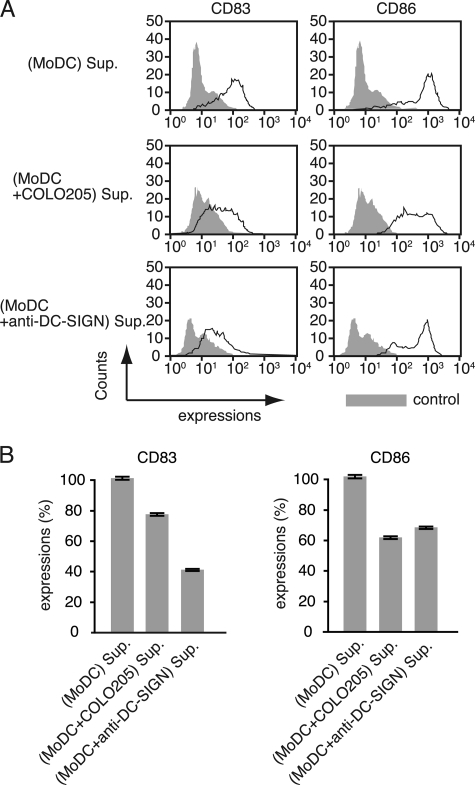

We previously demonstrated that the MoDC-SW1116 adhesion mediated by the glycosylation-dependent interactions between DC-SIGN and CEA resulted in dysfunctional MoDCs (9, 10). To determine whether or not this observation is also caused by the DC-SIGN-Mac-2BP interaction, we examined the effect of MoDC-COLO205 coculture condition on MoDC functional maturation. A coculture-derived supernatant was prepared from cocultures of COLO205 carcinoma cells and MoDCs after LPS stimulation. The addition of the MoDC-COLO205 coculture-derived supernatant to a new MoDC culture led to inhibition of maturation marker CD83 and activation marker CD86 expression compared with a MoDC culture-derived control supernatant (Fig. 6, A and B), suggesting that interaction between MoDCs and COLO205 cells causes suppression of LPS-induced functional maturation of MoDCs. Direct stimulation of MoDC with anti-DC-SIGN pAb also significantly suppressed MoDC maturation, suggesting that the DC-SIGN signaling cascade is sufficiently involved in MoDC maturation pathways. Collectively, our results indicate that the DC-SIGN-dependent interaction with COLO205-derived Mac-2BP as well as that with SW1116-derived CEA induces cellular adhesion between MoDCs and colorectal carcinoma cells, which impairs MoDC functional maturation.

FIGURE 6.

A COLO205-MoDC coculture-derived supernatant suppresses the functional maturation of MoDCs. A, flow cytometry analysis of CD83 and CD86 expressions. Immature MoDCs were incubated with a MoDC-cultured or COLO205-MoDC-cocultured supernatant (Sup.) for 3 days in the presence of IL-4, GM-CSF, and LPS (1 ng/ml), and the cultures were replenished with fresh supernatant on the second day. Supernatant of MoDCs, which cultured in the presence of anti-DC-SIGN pAb, was used as a control. The effect on MoDC functional maturation was determined as MoDC surface expression of CD83 and CD86 determined by flow cytometry. B, the relative expression levels of CD83 and CD86. The inhibition of MoDC functional maturation was measured as the percentage of mean fluorescent intensity (± S.E.) of incubation with MoDC-cultured supernatant. All experiments were performed in triplicate and were repeated a minimum of three times.

Mac-2BP Is a Major DC-SIGN Ligand in Some Primary Colorectal Carcinoma Tissues

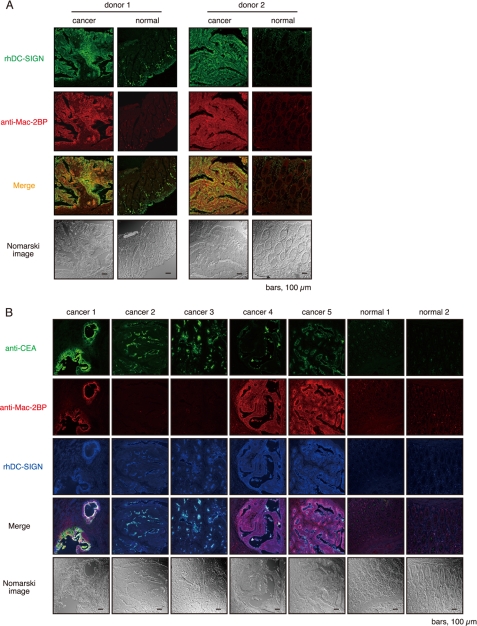

To determine whether or not DC-SIGN recognizes Mac-2BP in situ, human normal and malignant colon tissues from the same patients were double stained with rhDC-SIGN and anti-Mac-2BP pAb (Fig. 7A). As reported previously (12), Mac-2BP expression in malignant tissues was high in about half of the patients at mucosal epithelia compared with in normal tissues. Moreover, the staining pattern in the rhDC-SIGN markedly overlapped that of the Mac-2BP in the malignant epithelia (Fig. 7A), indicating that Mac-2BP, as a novel DC-SIGN ligand, is highly expressed on primary cancer colon epithelia, and implying that DC-SIGN is involved in the association between DCs and colorectal cancer cells in situ through recognition of these cancer-related Le glycan ligands.

FIGURE 7.

Mac-2BP expressed on colorectal cancer cells is a major target for DC-SIGN in situ. A, DC-SIGN recognizes colorectal carcinoma-derived Mac-2BP in situ. Primary colorectal cancer and normal colon tissues of donor 1 (SuperBioChips Laboratories) and donor 2 (Shiga University of Medical Science) were stained with rhDC-SIGN (green) and anti-Mac-2BP pAb (red). B, expressions of CEA and Mac-2BP in colorectal tumor tissues (SuperBioChips Laboratories). Triple staining of primary colorectal cancer and normal colon tissues with anti-CEA mAb (green), anti-Mac-2BP pAb (red), and rhDC-SIGN-allophycocyanin (blue). All samples were examined by confocal microscopy.

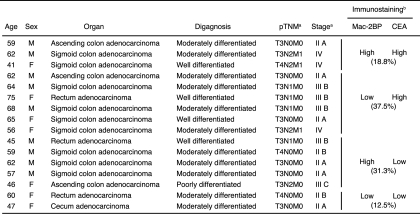

We and another group (9, 10) have recently reported that DC-SIGN recognizes CEA expressed in colorectal cancer tissues of patients. Therefore, to next examine the differences in expression pattern of and association with rhDC-SIGN between CEA and Mac-2BP, we performed triple staining with rhDC-SIGN, anti-Mac-2BP pAb, and anti-CEA mAb. In contrast to the CEA localization limited on the apical face of cancer epithelia, Mac-2BP expression exhibited a more diffuse pattern on both the apical and basolateral faces of epithelia in malignant colorectal cancer tissues, and little expression of either CEA or Mac-2BP was observed in colorectal normal tissues (Fig. 7B). Additionally, as shown in Fig. 7B, colorectal cancer patients could be divided into Mac-2BPhigh/CEAhigh (cancer 1), Mac-2BPlow/CEAhigh (cancer 2 and 3), Mac-2BPhigh/CEAlow (cancer 4 and 5), and Mac-2BPlow/CEAlow (data not shown) groups based on the distinct expression patterns of CEA and Mac-2BP together with the DC-SIGN recognition model. The profiles of Mac-2BP/CEA expression pattern-based groups were shown in Table 1. These results indicate that Mac-2BP may become a novel potential colorectal cancer biomarker for some patients with CEA-low or -negative colorectal cancer.

TABLE 1.

Pathological profile of Mac-2BP/CEA expression patterns in cancer tissues with rhDC-SIGN-staining positive specimens (n = 16)

a AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (6th Edition).

b Tissue specimens were stained with anti-CEA mAb and anti-Mac-2BP followed by Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary Abs.

DISCUSSION

During the neoplastic process in colon tissues, genetic or epigenetic gene alteration often accompanies changes in cell-surface glycans. Glycosylation changes during malignant transformation lead to tumor-specific carbohydrate structures that interact with C-type lectins on dendritic cells. In general, these changes have been associated with a poor prognosis, as they are linked to the aggressiveness and metastatic capacity of tumors. Good examples of heavily glycosylated tumor antigens are CEA and CEACAM1 (13–19), which can be secreted or expressed by colon cancer cells. Because the function of dendritic cells may be dependent on their binding properties as to self-antigens and pathogens, it is essential to obtain a detailed insight into the carbohydrate-binding properties of DC-SIGN.

Previous research indicated that tumor cells with their surface decorated with β1-6-branched N-linked oligosaccharides acquire invasiveness and metastatic potential through a change in the affinity level to the extracellular microenvironment (20, 21). Mac-2BP expressed on colorectal carcinoma cells was initially identified as a l-PHA-recognized major glycoprotein bearing polylactosamine glycans extending from β1-6 branched N-linked oligosaccharides (22, 23). In this study, we have firstly identified Mac-2BP on colorectal carcinoma cells as a novel ligand for C-type lectin DC-SIGN and demonstrated the Ca2+-dependent interaction of rhDC-SIGN with Mac-2BP from colorectal carcinoma COLO205 cells. Generally, DC-SIGN exhibits dual specificities for high-mannose as well as Le-type glycans (8, 24, 25). Foreign antigens recognized by DC-SIGN have both types of glycans. Whereas, so far, most endogenous ligands for DC-SIGN have been found to carry only Le-type glycans. Here we showed that specific removal of Le glycans on Mac-2BP by α1-3,4-fucosidase abrogated these interactions, indicating that the fucose moieties of Le glycans are required for the interactions. We also observed that DC-SIGN ligands are highly expressed with Le glycans on human colorectal carcinoma cells, suggesting that increased expression of DC-SIGN ligands on colorectal cancer cells in addition to altered glycosylation results in recognition by DC-SIGN and that further fucosylation of polylactosamine glycans and formation of Le epitopes on Mac-2BP during cancer progression may be important for induction of the interaction between DC-SIGN and Mac-2BP. In addition, we also found that the expression levels of Le epitopes were positively correlated with the staining levels with rhDC-SIGN in 30 colorectal carcinoma cell lines, including LoVo, LS513, LS174T, SNU1197, etc. (data not shown).

CEA is one of the most widely used tumor markers for gastrointestinal cancer such as colorectal carcinomas. It has been pointed out that the change in distribution of CEA from apical into basolateral and stromal areas in malignant colorectal cancer tissues could be a cause of its entry into the blood and elevation of the serum CEA levels (14, 16). However, the sensitivity and specificity of CEA are considered to be low, particularly for early stages of the disease such as Dukes A or B stages (26). We showed here that the distribution of Mac-2BP was more basolateral than that of CEA and that expression of Mac-2BP in primary colon adenocarcinoma tissues was increased compared with in proximal normal tissues and obtained various staining patterns for Mac-2BP such as luminal staining and punctate staining on the apical and basolateral faces (Fig. 7B). In addition, we observed here that DC-SIGN greatly associated with not only CEA but also Mac-2BP on the apical face of cancer epithelia and that DC-SIGN retained responsiveness to Mac-2BP in more basolateral areas. Because basolateral expression of Mac-2BP has been reported to be more prevalent in early stage Dukes A tumors than in advanced ones (12), DC-SIGN may preferably recognize early stage colorectal carcinoma cells through Mac-2BP. Therefore, similarly to that of CEA, aberrant expression of Mac-2BP and its polar breakdown in cancer tissues may allow its entry into blood vessels. Furthermore, it is also interesting that the type of Mac-2BP secreted by several colorectal carcinoma cells had DC-SIGN-detectable glycan structures, whereas we did not detect any binding of DC-SIGN to serum Mac-2BP from healthy donors (data not shown), suggesting that DC-SIGN can qualitatively distinguish colorectal carcinoma-derived Mac-2BP from serum Mac-2BP in normal and cancer patients.

Recent evidence indicates that dendritic cell-associated DC-SIGN may have functions in both the induction of tolerance to self-antigens and the recognition of pathogens, respectively. A variety of cytokines, including IL-6, IL-10, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), have been shown to affect the maturation of DCs from CD34+ precursors and from MoDCs in vitro (27, 28). Failure of the immune system to provide protection against tumor cells is an important immunological problem. It is now evident that inadequate functioning of the host immune system is one of the main mechanisms by which tumors escape from immune control, as well as an important factor that limits the success of cancer immunotherapy. In recent years, it has become increasingly clear that defects in DCs play a crucial role in non-responsiveness to tumors (29). Here, we showed that DC-SIGN-dependent cellular interactions between immature MoDCs and colorectal carcinoma cells significantly inhibited MoDC functional maturation, suggesting that, similar to CEA, Mac-2BP bearing colorectal tumor-associated Le glycans may provide a tolerogenic microenvironment for colorectal carcinoma cells through interactions with DC-SIGN. These findings also imply that the glycosylation-dependent cellular interactions may result in suppression of DC functions, possibly through immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-10, and that production of these immunosuppressive factors in DC tumor coculture supernatants may be one of the mechanisms by which tumors evade immunosurveillance.

Recently, the intracellular signaling mechanisms of DC-SIGN were elucidated (30–32). DC-SIGN constitutively associates with a signalosome complex consisting of scaffold protein LSP1 and mediates cross-talk with Toll-like receptor signaling, which results in modulation of Toll-like receptor-induced cytokine responses. Indeed, interaction of foreign pathogens such as M. tuberculosis leads to up-regulation of LPS-induced IL-10 and suppresses MoDC maturation (33). Therefore, the MoDC maturation as a consequence of DC-SIGN interacting with Le glycans of cancer cells may also be mediated through a series of LSP1-associated intracellular signaling pathway. MoDCs, following sensitization with CEA-derived peptides ex vivo, are now utilized as a tool for the clinical applications of tumor immunotherapies. As the immunogenicities of peptide vaccines vary among patients who exhibit different immune responsiveness, which is defined by means of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) types, etc., appropriate selection of antigens is needed individually to obtain adequate therapeutic benefit. In this context, colorectal carcinoma-derived Mac-2BP, similar to CEA, might become a candidate new cancer vaccine. Canceling of tumor-escaping mechanisms, such as DC-SIGN-mediated MoDC dysfunction, by combination of therapeutic agents that target intracellular signaling molecules (e.g. LSP1) may be a critical step for maintaining the effective tumor-immunogenicity in the future.

In conclusion, based on the distinct expression patterns of Mac-2BP and CEA together with the DC-SIGN recognition model presented here, colorectal cancer patients could be divided into Mac-2BPhigh/CEAhigh, Mac-2BPlow/CEAhigh, Mac-2BPhigh/CEAlow, and Mac-2BPlow/CEAlow groups. The establishment of a model of the DC-SIGN-Mac-2BP/CEA interaction is a valuable step toward elucidation of the physiological function and molecular mechanism and provides a knowledge-based approach for the clinical applications of cancer immunotherapies and novel diagnoses. For this purpose, identification of the DC-SIGN-Mac-2BP/CEA model that breaks immunotolerance to Mac-2BP/CEA and induces cancer immunosurveillance failure both in vitro and in vivo is therefore a major goal for therapeutic applications in the future.

Acknowledgment

We thank Tomoko Tominaga for secretarial assistance.

This work was supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research B 20370052 (to T. K.) and C 21590543 (to B. Y. M.), for Young Scientists Start-up 20890255 (to M. N.), and for Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Fellows 22-9530 (to M. N.) from JSPS, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, JSPS Core-to-Core Program Strategic Research Networks (17005) from JSPS, and Research Proposal Grants from Japan Foundation for Applied Enzymology (Osaka, Japan; to B. Y. M.).

- DC

- dendritic cell

- DC-SIGN

- DC-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin

- rhDC-SIGN-Fc

- recombinant human DC-SIGN-human IgG-Fc fusion protein

- pAb

- polyclonal Ab

- Mac-2BP

- Mac-2-binding protein

- CEA

- carcinoembryonic antigen

- MoDC

- monocyte-derived DC

- Le

- Lewis

- PHA

- phytohaemagglutinin

- AAL

- Aleuria aurantia agglutinin

- PNGase

- peptide N-glycosidase

- M-CSF

- macrophage colony-stimulating factor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Banchereau J., Briere F., Caux C., Davoust J., Lebecque S., Liu Y. J., Pulendran B., Palucka K. (2000) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 767–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lanzavecchia A., Sallusto F. (2001) Cell 106, 263–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Geijtenbeek T. B., van Vliet S. J., Engering A., ‘t Hart B. A., van Kooyk Y. (2004) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22, 33–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Vliet S. J., den Dunnen J., Gringhuis S. I., Geijtenbeek T. B., van Kooyk Y. (2007) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 19, 435–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Kooyk Y., Rabinovich G. A. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9, 593–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Geijtenbeek T. B., Kwon D. S., Torensma R., van Vliet S. J., van Duijnhoven G. C., Middel J., Cornelissen I. L., Nottet H. S., KewalRamani V. N., Littman D. R., Figdor C. G., van Kooyk Y. (2000) Cell 100, 587–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Geijtenbeek T. B., Torensma R., van Vliet S. J., van Duijnhoven G. C., Adema G. J., van Kooyk Y., Figdor C. G. (2000) Cell 100, 575–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Liempt E., Bank C. M., Mehta P., Garciá-Vallejo J. J., Kawar Z. S., Geyer R., Alvarez R. A., Cummings R. D., Kooyk Y., van Die I. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 6123–6131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Gisbergen K. P., Aarnoudse C. A., Meijer G. A., Geijtenbeek T. B., van Kooyk Y. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 5935–5944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nonaka M., Ma B. Y., Murai R., Nakamura N., Baba M., Kawasaki N., Hodohara K., Asano S., Kawasaki T. (2008) J. Immunol. 180, 3347–3356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grassadonia A., Tinari N., Iurisci I., Piccolo E., Cumashi A., Innominato P., D'Egidio M., Natoli C., Piantelli M., Iacobelli S. (2004) Glycoconj. J. 19, 551–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ulmer T. A., Keeler V., Loh L., Chibbar R., Torlakovic E., André S., Gabius H. J., Laferté S. (2006) J. Cell Biochem. 98, 1351–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Midiri G., Amanti C., Benedetti M., Campisi C., Santeusanio G., Castagna G., Peronace L., Di Tondo U., Di Paola M., Pascal R. R. (1985) Cancer 55, 2624–2629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hamada Y., Yamamura M., Hioki K., Yamamoto M., Nagura H., Watanabe K. (1985) Cancer 55, 136–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shi Z. R., Tsao D., Kim Y. S. (1983) Cancer Res. 43, 4045–4049 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahnen D. J., Nakane P. K., Brown W. R. (1982) Cancer 49, 2077–2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nittka S., Böhm C., Zentgraf H., Neumaier M. (2008) Oncogene 27, 3721–3728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shively J. E. (2004) Oncogene 23, 9303–9305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nittka S., Günther J., Ebisch C., Erbersdobler A., Neumaier M. (2004) Oncogene 23, 9306–9313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seelentag W. K., Li W. P., Schmitz S. F., Metzger U., Aeberhard P., Heitz P. U., Roth J. (1998) Cancer Res. 58, 5559–5564 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dennis J. W., Laferté S., Waghorne C., Breitman M. L., Kerbel R. S. (1987) Science 236, 582–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laferté S., Loh L. C. (1992) Biochem. J. 283, 193–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fernandes B., Sagman U., Auger M., Demetrio M., Dennis J. W. (1991) Cancer Res. 51, 718–723 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Appelmelk B. J., van Die I., van Vliet S. J., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C. M., Geijtenbeek T. B., van Kooyk Y. (2003) J. Immunol. 170, 1635–1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guo Y., Feinberg H., Conroy E., Mitchell D. A., Alvarez R., Blixt O., Taylor M. E., Weis W. I., Drickamer K. (2004) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 591–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duffy M. J. (2001) Clin. Chem. 47, 624–630 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Menetrier-Caux C., Montmain G., Dieu M. C., Bain C., Favrot M. C., Caux C., Blay J. Y. (1998) Blood 92, 4778–4791 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kiertscher S. M., Luo J., Dubinett S. M., Roth M. D. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 1269–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gabrilovich D. (2004) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 941–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gringhuis S. I., den Dunnen J., Litjens M., van Het Hof B., van Kooyk Y., Geijtenbeek T. B. (2007) Immunity 26, 605–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gringhuis S. I., van der Vlist M., van den Berg L. M., den Dunnen J., Litjens M., Geijtenbeek T. B. (2010) Nat. Immunol. 11, 419–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gringhuis S. I., den Dunnen J., Litjens M., van der Vlist M., Geijtenbeek T. B. (2009) Nat. Immunol. 10, 1081–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Geijtenbeek T. B., Van Vliet S. J., Koppel E. A., Sanchez-Hernandez M., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C. M., Appelmelk B., Van Kooyk Y. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 197, 7–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]