Abstract

Phosphorylation of rhodopsin by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 1 (GRK1, or rhodopsin kinase) is critical for the deactivation of the phototransduction cascade in vertebrate photoreceptors. Based on our previous studies in vitro, we predicted that Ser21 in GRK1 would be phosphorylated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) in vivo. Here, we report that dark-adapted, wild-type mice demonstrate significantly elevated levels of phosphorylated GRK1 compared with light-adapted animals. Based on comparatively slow half-times for phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, phosphorylation of GRK1 by PKA is likely to be involved in light and dark adaptation. In mice missing the gene for adenylyl cyclase type 1, levels of phosphorylated GRK1 were low in retinas from both dark- and light-adapted animals. These data are consistent with reports that cAMP levels are high in the dark and low in the light and also indicate that cAMP generated by adenylyl cyclase type 1 is required for phosphorylation of GRK1 on Ser21. Surprisingly, dephosphorylation was induced by light in mice missing the rod transducin α-subunit. This result indicates that phototransduction does not play a direct role in the light-dependent dephosphorylation of GRK1.

Keywords: Cyclic AMP (cAMP), Photoreceptors, Phototransduction, Protein Kinase A (PKA), Protein Phosphorylation, Retina, Rhodopsin, G Protein-coupled Receptor Kinase 1 (GRK1)

Introduction

The ability of rod and cone photoreceptors in the vertebrate retina to adjust the speed and sensitivity of their responses to changing intensities of light is essential for normal visual function. Photoreceptors respond to light stimuli within milliseconds and rapidly terminate signaling to recover and maintain their sensitivity under constantly changing ambient light. In rods, G protein-coupled receptor kinase 1 (GRK1)3 contributes to signal turnoff via phosphorylation of rhodopsin, the G protein-coupled receptor that initiates the phototransduction cascade. Phosphorylation is followed by the binding of arrestin to rhodopsin, which sterically blocks the interaction of rhodopsin with its G protein, transducin (1, 2). GRK1 is expressed in rods of all vertebrates and in cones in several vertebrates (3). For example, GRK1 is expressed in both rods and cones in mice, where it phosphorylates rhodopsin and the cone opsins, respectively (4–6). In humans, inactivating mutations in GRK1 result in severe defects in rod phototransduction, causing stationary night blindness as well as mild defects in cone phototransduction (7–9).

GRK1 is regulated allosterically by its substrate so that it only phosphorylates light-activated rhodopsin as part of a precisely timed mechanism of deactivation in response to light (10, 11). We have proposed a novel mechanism for regulating GRK1 activity via phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), based on the reduced ability of phosphorylated GRK1 to phosphorylate rhodopsin in vitro (12). In the present report, we demonstrate that GRK1 is a substrate for PKA in vivo. We show that phosphorylation of GRK1 is high in the dark and low in the light. The rate of change in the phosphorylation state of GRK1 is comparatively slow, possibly contributing to the ability of photoreceptors to adapt to continuously changing levels of light. Our findings introduce the exciting possibility that cAMP plays a role in regulating the lifetime of rhodopsin by altering the activity of GRK1 during dark and light adaptation. Unexpectedly, light-dependent dephosphorylation of GRK1 in mice missing the transducin α subunit was normal, indicating that a pathway other than phototransduction may be involved in the regulation of GRK1 dephosphorylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies

A monoclonal antibody directed against GRK1 (D11) was purchased from Affinity Bioreagents (Rockford, IL). An antibody directed against GRK1 phosphorylated at Ser21 (anti-pGRK1) was generated against a phosphopeptide corresponding to amino acids 16–28 of mouse GRK1 (IAARG[pS]FDGSSTP) by 21st Century Biochemicals (Marlboro, MA). Secondary antibodies for immunoblot analysis (Alexa Fluor 680 goat anti-rabbit IgG and IRDye800 goat anti-mouse IgG) and immunocytochemistry (Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-mouse IgG) were purchased from Invitrogen or Fisher Scientific.

Mice

All mice were in a C57BL/6 background, except for the Trα−/− mice, which were in a 129SV background. Therefore, in experiments using the Trα−/− mice, wild-type mice in the 129SV background were used as controls. Mice were raised under a normal 12-h light/12-h dark cycle except for the Arr−/− mice, which were raised in the dark to prevent light-dependent retinal degeneration (13).

Analysis of GRK1 Phosphorylation

Animals were dark- or light-adapted for the indicated times, followed by euthanasia using procedures in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. For immunoblot analysis, eyes were enucleated and the retinas removed under infrared light or under a light intensity of ∼1,500 lux in HEPES-Ringer buffer containing 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 120 mm sodium chloride, 0.5 mm potassium chloride, 0.2 mm calcium chloride, 0.2 mm magnesium chloride, 0.1 mm EDTA, 10 mm glucose, 1 mm DTT (14). Each retina was placed in 100 μl of HEPES-Ringer buffer, followed by the addition of 150 μl of heated (95 °C) buffer containing 125 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, and 100 mm NaF for homogenization using a motorized pestle. The homogenates were heated for 3 min at 95 °C and sheared with a 25-gauge needle. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 25 °C and the supernatant collected for protein determination. After adding bromphenol blue and β-mercaptoethanol, 25 μg of sample protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis. Nitrocellulose membranes were preincubated in Odyssey Blocking Buffer (Licor Biosciences, Lincoln, NB) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with antibodies at the following dilutions: anti-pGRK1, 1:1,000; anti-GRK1, 1:10,000. After incubation with secondary antibodies at 1:10,000, the blots were analyzed using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Licor Biosciences). For experiments in Fig. 6, retinas were removed as described above and incubated ex vivo in 100 μl of HEPES-Ringer solution containing the adenylyl cyclase activator, forskolin, or the phosphodiesterase inhibitor, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, as described in the legend to Fig. 6.

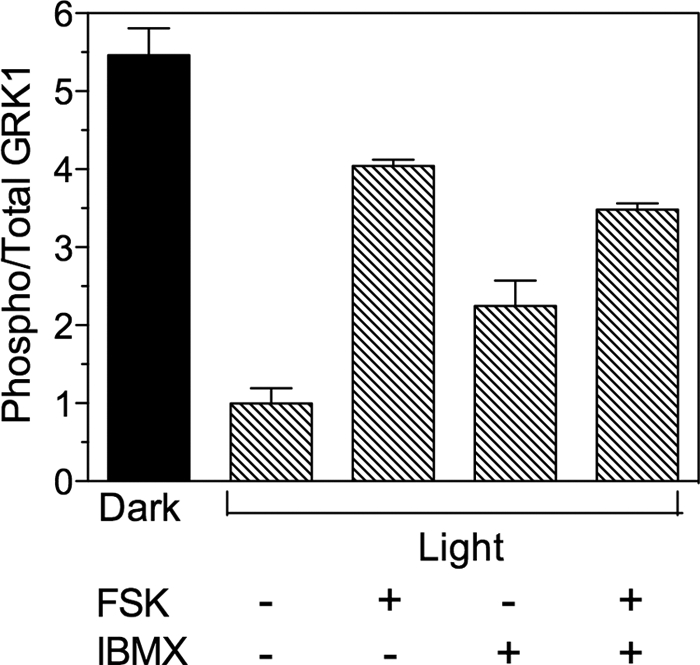

FIGURE 6.

Phosphorylation of GRK1 in retinas ex vivo. One mouse (−light) was dark-adapted overnight and dissected under infrared light. The other mice were exposed to 1,500 lux (+light) for 3–6 h prior to euthanasia. Retinas dissected from light-exposed mice were incubated in the light in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 20 μm forskolin (FSK) and 1 mm 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) in HEPES-Ringer buffer for 30 min, followed by homogenization and immunoblot analysis. Error bars represent the range of duplicate samples.

For immunocytochemistry, enucleation was followed by incubation overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C and washing three times in PBS. Eyes were cryoprotected and sectioned as described (15). Sections were rehydrated for 5 min in PBS, followed by a 5-min incubation at room temperature in 1% SDS in PBS, washed three times for 5 min each in PBS, and incubated with antibodies at the following dilutions: anti-pGRK1, 1:100; anti-GRK1, 1:10,000. Additional washes and incubation with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-mouse IgG at 1;1,000) were performed as described (15). Images were collecting using a Nikon Eclipse 400 Epifluorescent microscope (see Fig. 3A) or a Nikon Eclipse 90i confocal microscope (see Fig. 3B).

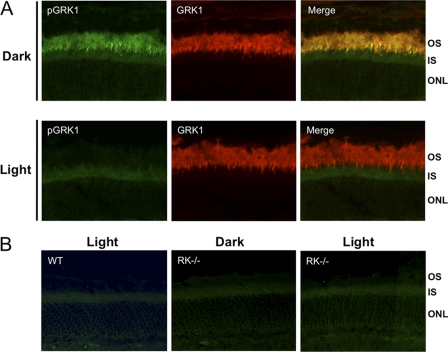

FIGURE 3.

Immunocytochemical analysis of phosphorylated GRK1 in dark- and light-adapted mice. Mice were dark- or light-adapted as described in the legend for Fig. 2, followed by euthanasia and removal of the eyes. Eyecups were fixed as described under “Materials and Methods. ” A, sections from dark- and light-adapted wild-type (WT) mouse retinas were double-labeled with anti-pGRK1 and anti-GRK1. B, retina sections from light-adapted WT mice and dark-reared GRK1 knock-out (RK−/−) mice, which were euthanized and enucleated in the dark or light-adapted prior to euthanasia, were labeled with anti-pGRK1. OS, outer segment; IS; inner segment; ONL; outer nuclear layer.

Label-free Peptide Quantification by Mass Spectrometry

The photoreceptor layer from a flat-mounted frozen retina was isolated in a series of 10-mm tangential sections, and the peptide composition of each section was analyzed by label-free quantitative mass spectrometry (16). Briefly, two 60-day-old pigmented Long-Evans rats (Rattus norwegicus) were dark-adapted for at least 12 h and sacrificed under dim red light either immediately or following a 1-h exposure to bright light producing 15,000 lux on the cornea surface as described (17). Serial tangential sectioning was performed as described by Sokolov et al. (18) with modifications described by Strissel et al. (19) and Lobanova et al. (17). Each retina section was dissolved in 50 μl of 0.5% v/v AALS II (Anionic Acid-Liable Surfactant; Protea Biosciences, Morgantown, WV), followed by sonication and boiling for 5 min. Cysteine residues were reduced with 10 mm DTT and alkylated with 20 mm iodoacetamide. Proteins were digested with trypsin (15 ng/μl) overnight at 37 °C. Peptide digests obtained from each of the 24 sections (12 from each retina) were analyzed using a nanoAcquity UPLC system coupled to a Synapt HDMS mass spectrometer (Waters Corp., Milford, MA). Tandem MS data including phosphorylation as a variable modification were obtained in the data-dependent acquisition mode and searched against the NCBInr protein data base. These data are available online in the form of a Scaffold 3 file (.sf3, Proteome Software, Inc.).4

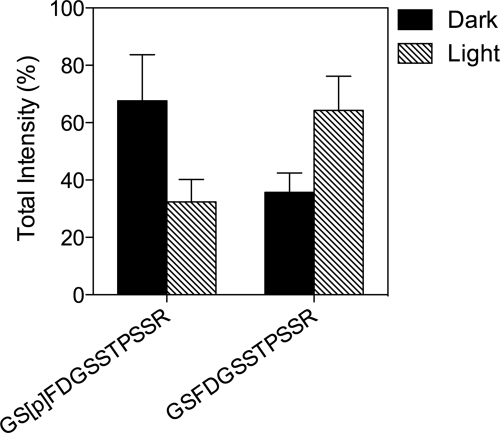

The total intensities (calculated as a sum of ion chromatogram peak areas for a given peptide obtained by LC/MS analyses added across the first five sections, which represent outer segments, based on rhodopsin content) of the phosphorylated peptide corresponding to amino acids 20–31 of rat GRK1 (GS[p]FDGSSTPSSR, 1,263.499 Da) and the unphosphorylated peptide (GSFDGSSTPSSR, 1,183.499 Da) were measured in duplicate. The raw intensity data for each peptide can be found in lines 1464 and 1466 of supplemental Table 1 in Ref. 16.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical comparison of multiple groups was performed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test. Comparisons in Fig. 8B were performed using a Student's t test.

FIGURE 8.

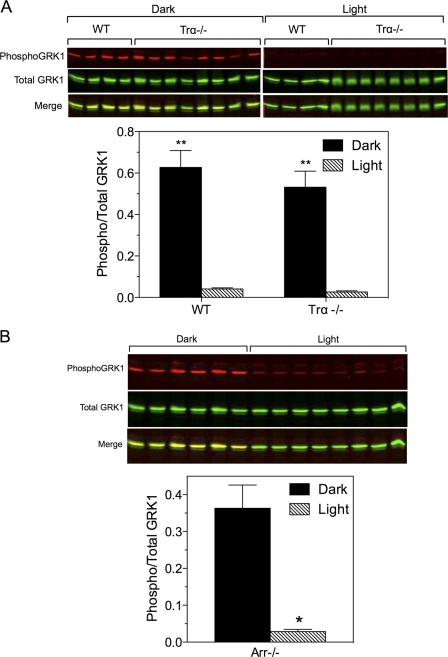

Phosphorylation of GRK1 and phosducin in Trα−/− and Arr−/− mice. A, wild-type and Trα−/− mice were dark-adapted overnight, then maintained in the dark or exposed to light for 2–3 h, euthanized, and the retinas were dissected for immunoblot analysis. Upper panel, Western blot of samples collected from two experiments. Lower panel, quantitative analysis of data shown above. Error bars represent S.E., n = 4 for each WT group; n = 8 for each Trα−/− group; **, p < 0.001 dark versus light. B, Arr−/− mice were dark-adapted overnight and exposed to light for 30–40 min. Upper panel, Western blot of samples collected from a single experiment. Lower panel, quantitative analysis of the data shown above. n = 6 (dark) and 8 (light); *, p < 0.0001 versus dark.

RESULTS

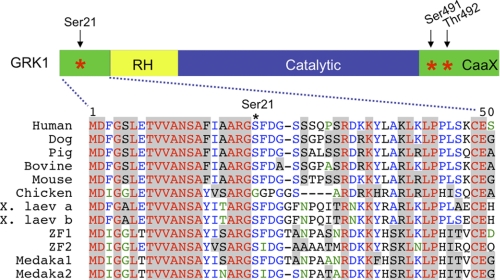

Previously, we showed that phosphorylation of GRK1 on Ser21 by PKA in vitro reduces its ability to phosphorylate rhodopsin, suggesting a role for this posttranslational modification in phototransduction (12). This potential phosphorylation site is conserved from fish to mammals (with the interesting exception of chicken GRK1) (Fig. 1), an evolutionary time scale of ∼400 million years (20). Evolutionary conservation of PKA phosphorylation sites often predicts phosphorylation in vivo and strongly correlates with the physiological significance of phosphorylation (21). Structural and mutagenesis studies also predict that the amino terminus of GRK1 is positioned to play a role in the interaction of the kinase with rhodopsin (22–24) Thus, the fact that Ser21 is phosphorylated by PKA in vitro and is highly conserved in vertebrate evolution suggests that it is phosphorylated in vivo and that phosphorylation has an important physiological role in GRK function.

FIGURE 1.

Ser21 is conserved in most vertebrates. The serine phosphorylated by PKA, Ser21, and the autophosphorylation sites, Ser491 and Thr492, are marked with asterisks (*) (12, 53). RH, RGS homology domain; CaaX, isoprenylation motif; X. laev, Xenopus laevis; ZF, zebrafish (Danio rerio); Medaka, medaka fish. The alignment was performed using the software program, VectorNTI (Invitrogen).

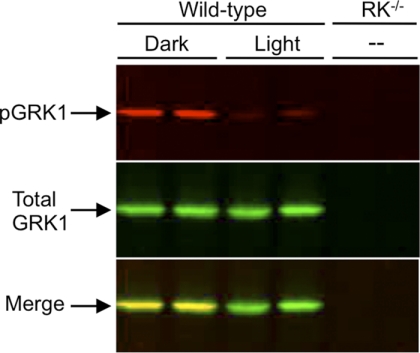

To determine whether GRK1 is phosphorylated in vivo, wild-type mice were dark-adapted overnight, euthanized under infrared light, or exposed to bright light for 1 h prior to euthanasia. Using an antibody specific for mouse GRK1 phosphorylated on Ser21 (anti-pGRK1), immunoblot analysis of the retinas demonstrate that phosphorylation is high in dark-adapted mice and low in mice exposed to light (Fig. 2). In contrast, the levels of total GRK1 are unchanged. Immunocytochemical analysis shown in Fig. 3A reveal an elevated level of phosphorylated GRK1 in rod outer segments of dark-adapted mice compared with light-adapted animals. The merged images display colocalization of phosphorylated and total GRK1 in rod outer segments, consistent with previously published work indicating that GRK1 is primarily located in rod outer segments (25). A comparison of retinas from light-adapted wild-type mice with those from light- and dark-adapted GRK1 knock-out (RK−/−) mice stained with anti-pGRK1 demonstrates that the weak staining observed in the inner segment is nonspecific (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 2.

Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated GRK1 in dark- and light-adapted mouse retinas. Mice were dark-adapted overnight and then exposed to 1,500 lux for 1 h or maintained in the dark. After euthanasia, the retinas were removed for immunoblot analysis. The blots were double-labeled with an antibody that recognizes GRK1 phosphorylated on Ser21 (anti-pGRK1; top panel) and an antibody that recognizes total GRK1 (anti-GRK1; middle panel). Retinas from dark-reared mice null for GRK1 (RK−/−) were used as a control. Bottom panel, merged image.

Using an entirely independent method to identify phosphorylated and unphosphorylated GRK1, we separated the outer segment layer from dark- and light-adapted rat retinas by freezing and tangential sectioning and identified the phosphorylation status of Ser21 by mass spectrometry as described previously (16). Two peptides were identified by tandem MS analysis corresponding to amino acids 20–31 of rat GRK1: the unphosphorylated peptide (GSFDGSSTPSSR) and a peptide phosphorylated at a serine corresponding to Ser21 (GS[p]FDGSSTPSSR) (Fig. 4). The relative amount of phosphorylated peptide, determined from the peak areas of the corresponding ion chromatograms, was elevated in the dark-adapted rats. Conversely, the unphosphorylated peptide was present in greater quantities in light-adapted animals. Taken together, the immunoblot, immunohistochemical, and mass spectrometry data indicate that Ser21 is phosphorylated and dephosphorylated in vivo in a light-dependent manner, strengthening our hypothesis that this phosphorylation contributes to the function of GRK1.

FIGURE 4.

Mass spectrometry analysis of GRK1 phosphorylated on Ser21 in photoreceptor cells. Retinas from dark- and light-adapted rats were processed for serial, tangential sectioning as described under “Materials and Methods. ” The sections were compared by mass spectrometry for changes in levels of a phosphopeptide corresponding to amino acids 20–31 of rat GRK1 phosphorylated on Ser21 compared with the corresponding unphosphorylated peptide. Error bars represent the range of duplicate dark and light analyses.

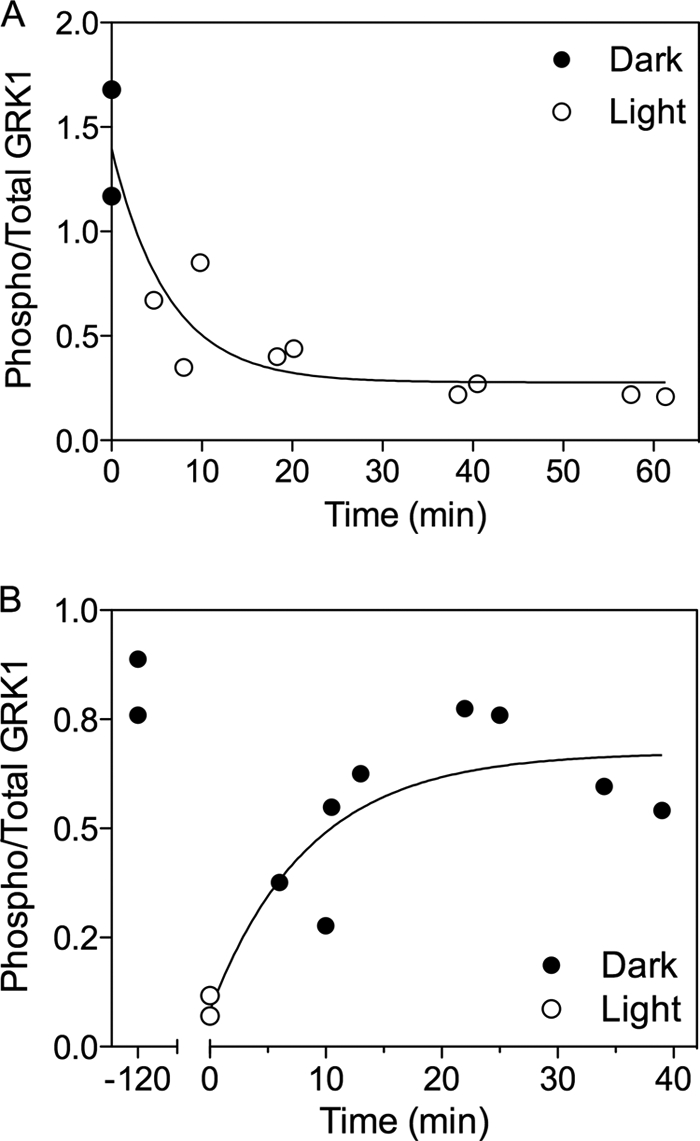

A time course analysis was performed to determine how rapidly light exposure results in the loss of phosphorylated GRK1. When dark-adapted mice were placed in the light, GRK1 was dephosphorylated in vivo with a half-time of ∼4 min (Fig. 5A). Similarly, mice that were light-adapted for 2 h then dark-adapted for various times, exhibited an increase in phosphorylated GRK1 with a half-time of ∼5 min (Fig. 5B). These relatively slow changes in phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are consistent with an influence on dark and light adaptation.

FIGURE 5.

Time course of GRK1 phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. A, mice were dark-adapted overnight, then exposed to 1,500 lux for the indicated time periods. B, mice were exposed to 1,500 lux for 2 h and returned to the dark for the indicated time periods. Each point represents the time at which a single retina was solubilized in SDS-containing buffer for immunoblot analysis. Each experiment is representative of at least two independent experiments.

Although phototransduction has been studied extensively, there are still unknown factors that influence the timing and amplification of signaling under conditions of sustained illumination (26, 27). Previously, we showed that recombinant GRK1 can be phosphorylated in retina extracts by an endogenous kinase (12). To establish the identity of this kinase, we incubated retinas removed from light-adapted mice with forskolin, an activator of adenylyl cyclase, and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, which raises cyclic nucleotide levels by inhibiting phosphodiesterase activity. The data in Fig. 6 indicate that stimulation of cAMP synthesis and/or inhibition of its breakdown indeed results in phosphorylation of GRK1.

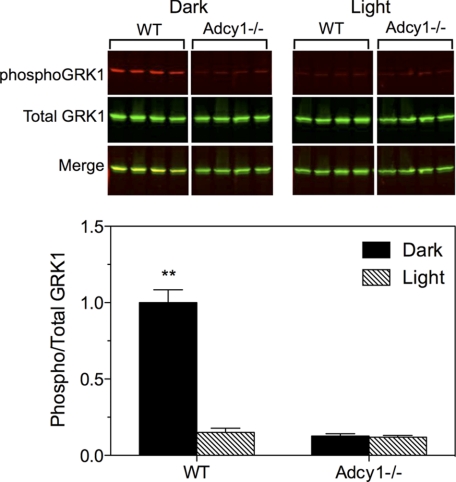

Adenylyl cyclase type 1 (AC1) is a Ca2+/calmodulin-sensitive isoform of adenylyl cyclase that is selectively expressed in the brain and the neural retina (28). AC1 was previously identified as the primary enzyme for synthesis of cAMP in photoreceptor cells (29). To determine whether AC1 contributes to the phosphorylation of GRK1, AC1 knock-out (Adcy1−/−) mice (30) were evaluated. Compared with wild-type mice, retinas from Adcyl−/− mice displayed very little phosphorylation of GRK1 under either light- or dark-adapted conditions (Fig. 7). These data indicate that phosphorylation of GRK1 by PKA requires AC1. Because AC1 is regulated by Ca2+/calmodulin, we speculated that its activity is influenced by the reduction in intracellular Ca2+ that occurs during the photoresponse (31). This hypothesis predicts that mice null for Gαt (Trα−/− mice) would not exhibit light-dependent dephosphorylation of PKA-phosphorylated substrates because Ca2+ levels in these mice do not change in the absence of phototransduction (32). Surprisingly, phosphorylation of GRK1 on Ser21 was high in the dark and low in the light in Trα−/− mice (Fig. 8A), indicating that GRK1 dephosphorylation is independent of phototransduction.

FIGURE 7.

Phosphorylation of GRK1 in retinas from Adcy1−/− mice. Mice were dark-adapted overnight, then exposed to light (1,500 lux) for 2 h or maintained in the dark prior to euthanasia and removal of retinas. Retinas were processed for Western blot analysis to evaluate levels of phosphorylated and total GRK1. Upper panel, representative Western blot; lower panel, average of duplicate experiments. Error bars represent S.E., n = 8. **, p < 0.001 versus all other groups.

Because the binding of visual arrestin to light-activated, phosphorylated rhodopsin is independent of Gtα1, it is possible that arrestin could signal via an unknown pathway to mediate dephosphorylation of GRK1 in rods, as observed for arrestin2 and arrestin3 in different cell types (e.g. 33). We tested this hypothesis by analyzing the phosphorylation of GRK1 in arrestin knock-out (Arr−/−) mice. The results show that dephosphorylation of GRK1 occurs in the absence of arrestin (Fig. 8B). Therefore, neither transducin nor arrestin is necessary for the light-dependent dephosphorylation of GRK1.

DISCUSSION

The present report describes the phosphorylation of GRK1 on Ser21 by PKA in mouse photoreceptor cells. The level of phosphorylation is high in the dark and low in the light. Ser21 is part of an α-helical domain in the amino terminus that is structurally conserved across the GRK family of proteins. Biochemical and structural studies indicate that this region generally plays a role in receptor interaction, leading to allosteric activation of the kinase (22, 24, 34), possibly through interaction with the hinge region of the RGS homology domain and a region of the kinase domain of the carboxyl terminus (23, 35). Although Ser21 is visualized in the crystal structure of GRK1, its potential interactions with rhodopsin or regions of the kinase have not been defined. Previously, we reported that the cone-specific GRK, GRK7, is similarly phosphorylated on Ser36 in cones of dark-adapted animals (15). Mice do not have the gene for GRK7 and, instead, express only GRK1 in both rods and cones (3). Our prior studies in vitro indicate that phosphorylation of rhodopsin is reduced when GRK1 is phosphorylated by PKA (12). Because cAMP levels in photoreceptor cells are elevated in the dark and decline upon light exposure (36, 37), our data suggest a novel mechanism whereby the lifetime of rod and cone opsins may be influenced by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the GRKs.

There are a number of potential mechanisms that may contribute to light adaptation in rods, including changes in the catalytic gain and lifetime of rhodopsin (38). The lifetime of rhodopsin is limited by the rate of its phosphorylation by GRK1 followed by arrestin binding, which both take place within 40–54 ms from onset of the light response (39, 40). However, phosphorylation of GRK1 by PKA in the dark and dephosphorylation in the light are much slower processes, with t½ values of ∼5 and 4 min, respectively. Therefore, phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of GRK1 may serve as a novel mechanism that contributes to long term adaptation of rod photoreceptors to the continually changing light environment by modifying the activity of GRK1 toward its substrate, rhodopsin; that is, rhodopsin phosphorylation may be slower in dark-adapted rods characterized by larger and longer electrical responses and faster in light-adapted rods, where photoresponses are smaller and shorter. Several groups have attempted to characterize the various factors responsible for light adaptation and determined that different mechanisms might be functioning during distinct phases of adaptation. For example, Calvert et al. (26) noted two phases of adaptation: the better characterized fast phase with a time constant of 1–2 s, and a slower phase observed only at high light intensities. Burns and co-workers also identified a novel mechanism of adaptation, known as adaptive acceleration, which accelerates recovery and persists for many seconds (27). Other contributions to long term adaptation include translocation of transducin, arrestin, and recoverin (but not GRK1) (25), which occurs on the order of minutes (41). Future studies using transgenic mice with mutations at Ser21 are aimed at addressing the role of phosphorylation by PKA.

Our studies also raise questions regarding the signaling pathway whereby cAMP is generated and how that pathway is regulated by light. As described above, cAMP in mouse photoreceptor cells is synthesized by Ca2+/calmodulin-sensitive AC1 (29). The authors observed a dramatic reduction in cAMP levels and the loss of light-dependent regulation of adenylyl cyclase activity in Adcy1−/− mice. Consistent with our hypothesis that PKA, activated by cAMP, phosphorylates GRK1 on Ser21, we also observed an absence of GRK1 phosphorylation in the dark in the Adcy1−/− mice. It is known that AC1 is synergistically activated by Gs and Ca2+/calmodulin (42). Although it has not been proven that AC1 is controlled by Ca2+/calmodulin in photoreceptor cells, it seems reasonable that Ca2+ plays a prominent role, given that the EC50 for AC1 is ∼100–150 nm (30) and that Ca2+ concentrations vary from 250 nm to 23 nm in dark- and light-adapted rod outer segments, respectively (32). Surprisingly, the Trα−/− mice displayed normal, light-dependent dephosphorylation of GRK1, despite maintaining elevated levels of Ca2+. Previously, Rajala et al. (43) reported that phosphorylation of the insulin receptor on tyrosine is high in the light and low in the dark, even in Trα−/− mice and speculated that arrestin may activate a signaling pathway that is independent of transducin. However, we found that the light-dependence of GRK1 dephosphorylation in Arr1−/− mice was also normal. Although feedback from cones or other cells in the retina could explain our results, it is also possible that there are unknown binding partners for rhodopsin. For example, rhodopsin may couple to other members of the Gi/Go family, as has been shown by us and others in cultured cells (44–46). It is also not clear whether the light-dependent decline in phosphorylation is mediated entirely by changes in adenylyl cyclase and kinase activity or whether changes in phosphodiesterase and phosphatase activities may be more important in determining the dephosphorylated state of GRK1.

Phosphorylation of GRK family members by a variety of serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases has been shown to play a significant role in localization, stability, and (in the case of GRK2 and GRK3) interaction with βγ in cultured cells (47). The present report is, to our knowledge, the first example of phosphorylation demonstrated in native tissue. Other substrates for PKA in dark-adapted photoreceptor cells include phosducin (48, 49), arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase, a key enzyme for melatonin synthesis (50), and connexin 35, located at gap junctions between rods and cones in zebrafish (51). These proteins are located in different compartments in photoreceptor cells, suggesting that cAMP has a broad influence on multiple aspects of photoreceptor cell function, ranging from circadian-induced shedding of photoreceptor outer segments to rod-cone coupling. Cyclic AMP has been localized primarily to the inner segment and outer nuclear layer in dark-adapted rats (52). However, the ability of cAMP to diffuse rapidly throughout the cell suggests that it could be active in numerous compartments. Analysis of the major components of the cAMP signaling pathway, including the regulatory and catalytic subunits of PKA, will lead to a better understanding of its contribution to the function of GRK1 and its role in the response of photoreceptor cells to light.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Daniel Storm, Janis Lem, Maxim Sokolov, and Ching-Kang Chen for mice; Drs. M. Arthur Moseley, J. Will Thompson, and Nikolai P. Skiba for help in performing mass spectrometry; and Dr. Raju Rajala for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY072224 (to E. R. W.), EY10336 (to V. Y. A.), and R01EY004864 (to P. M. I.) and National Institutes of Health Core Grants for Vision Research EY5722 (to V. Y. A. and E. R. W.) and EY006360 (to P. M. I.) This work was also supported by Research to Prevent Blindness (to P. M. I.).

For access to the database, please send a message to V. Y. Arshavsky (vadim.arshavsky@duke.edu).

- GRK

- G protein-coupled receptor kinase

- AC1

- adenylyl cyclase type 1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wilden U., Hall S. W., Kühn H. (1986) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 1174–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wilden U., Kühn H. (1982) Biochemistry 21, 3014–3022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weiss E. R., Ducceschi M. H., Horner T. J., Li A., Craft C. M., Osawa S. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 9175–9184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen C. K., Burns M. E., Spencer M., Niemi G. A., Chen J., Hurley J. B., Baylor D. A., Simon M. I. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3718–3722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lyubarsky A. L., Chen C., Simon M. I., Pugh E. N., Jr. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 2209–2217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maeda T., Imanishi Y., Palczewski K. (2003) Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 22, 417–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cideciyan A. V., Jacobson S. G., Gupta N., Osawa S., Locke K. G., Weiss E. R., Wright A. F., Birch D. G., Milam A. H. (2003) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44, 1268–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cideciyan A. V., Zhao X., Nielsen L., Khani S. C., Jacobson S. G., Palczewski K. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 328–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dryja T. P. (2000) Am. J. Ophthalmol. 130, 547–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fowles C., Sharma R., Akhtar M. (1988) FEBS Lett. 238, 56–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palczewski K., Buczylko J., Kaplan M. W., Polans A. S., Crabb J. W. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 12949–12955 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Horner T. J., Osawa S., Schaller M. D., Weiss E. R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28241–28250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen J., Simon M. I., Matthes M. T., Yasumura D., LaVail M. M. (1999) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 40, 2978–2982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee B. Y., Thulin C. D., Willardson B. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 54008–54017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Osawa S., Jo R., Weiss E. R. (2008) J. Neurochem. 107, 1314–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reidel B., Thompson J. W., Farsiu S., Moseley M. A., Skiba N. P., Arshavsky V. Y. (2011) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, M110.002469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lobanova E. S., Finkelstein S., Song H., Tsang S. H., Chen C. K., Sokolov M., Skiba N. P., Arshavsky V. Y. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 1151–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sokolov M., Lyubarsky A. L., Strissel K. J., Savchenko A. B., Govardovskii V. I., Pugh E. N., Jr., Arshavsky V. Y. (2002) Neuron 34, 95–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Strissel K. J., Sokolov M., Trieu L. H., Arshavsky V. Y. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 1146–1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Futuyama D. J. (1998) Evolutionary Biology, 3rd Ed., p. 130, Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 21. Budovskaya Y. V., Stephan J. S., Deminoff S. J., Herman P. K. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 13933–13938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Palczewski K., Buczylko J., Lebioda L., Crabb J. W., Polans A. S. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 6004–6013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Singh P., Wang B., Maeda T., Palczewski K., Tesmer J. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14053–14062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yu Q. M., Cheng Z. J., Gan X. Q., Bao G. B., Li L., Pei G. (1999) J. Neurochem. 73, 1222–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Strissel K. J., Lishko P. V., Trieu L. H., Kennedy M. J., Hurley J. B., Arshavsky V. Y. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29250–29255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Calvert P. D., Govardovskii V. I., Arshavsky V. Y., Makino C. L. (2002) J. Gen. Physiol. 119, 129–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Krispel C. M., Chen C. K., Simon M. I., Burns M. E. (2003) J. Gen. Physiol. 122, 703–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xia Z., Choi E. J., Wang F., Blazynski C., Storm D. R. (1993) J. Neurochem. 60, 305–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jackson C. R., Chaurasia S. S., Zhou H., Haque R., Storm D. R., Iuvone P. M. (2009) J. Neurochem. 109, 148–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu Z. L., Thomas S. A., Villacres E. C., Xia Z., Simmons M. L., Chavkin C., Palmiter R. D., Storm D. R. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 220–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Burns M. E., Pugh E. N., Jr. (2010) Physiology 25, 72–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Woodruff M. L., Sampath A. P., Matthews H. R., Krasnoperova N. V., Lem J., Fain G. L. (2002) J. Physiol. 542, 843–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lefkowitz R. J., Shenoy S. K. (2005) Science 308, 512–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Noble B., Kallal L. A., Pausch M. H., Benovic J. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47466–47476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huang C. C., Orban T., Jastrzebska B., Palczewski K., Tesmer J. J. (2011) Biochemistry 50, 1940–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cohen A. I., Blazynski C. (1990) Vis. Neurosci. 4, 43–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Farber D. B., Souza D. W., Chase D. G., Lolley R. N. (1981) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 20, 24–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pugh E. N., Jr., Nikonov S., Lamb T. D. (1999) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 9, 410–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen C. K., Woodruff M. L., Chen F. S., Chen D., Fain G. L. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 1213–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gross O. P., Burns M. E. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 3450–3457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Calvert P. D., Strissel K. J., Schiesser W. E., Pugh E. N., Jr., Arshavsky V. Y. (2006) Trends Cell Biol. 16, 560–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ferguson G. D., Storm D. R. (2004) Physiology 19, 271–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rajala A., Anderson R. E., Ma J. X., Lem J., Al-Ubaidi M. R., Rajala R. V. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9865–9873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weiss E. R., Heller-Harrison R. A., Diez E., Crasnier M., Malbon C. C., Johnson G. L. (1990) J. Mol. Endocrinol. 4, 71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dickerson C. D., Weiss E. R. (1995) Exp. Cell Res. 216, 46–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li X., Gutierrez D. V., Hanson M. G., Han J., Mark M. D., Chiel H., Hegemann P., Landmesser L. T., Herlitze S. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 17816–17821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Penela P., Ribas C., Mayor F., Jr. (2003) Cell. Signal. 15, 973–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bauer P. H., Müller S., Puzicha M., Pippig S., Obermaier B., Helmreich E. J., Lohse M. J. (1992) Nature 358, 73–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lee R. H., Brown B. M., Lolley R. N. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 15860–15866 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pozdeyev N., Taylor C., Haque R., Chaurasia S. S., Visser A., Thazyeen A., Du Y., Fu H., Weller J., Klein D. C., Iuvone P. M. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 9153–9161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li H., Chuang A. Z., O'Brien J. (2009) J. Neurosci. 29, 15178–15186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Traverso V., Bush R. A., Sieving P. A., Deretic D. (2002) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 1655–1661 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Palczewski K., Buczylko J., Van Hooser P., Carr S. A., Huddleston M. J., Crabb J. W. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 18991–18998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]