Abstract

Trypanosoma congolense is an African trypanosome that causes serious disease in cattle in Sub-Saharan Africa. The four major life cycle stages of T. congolense can be grown in vitro, which has led to the identification of several cell-surface molecules expressed on the parasite during its transit through the tsetse vector. One of these, glutamic acid/alanine-rich protein (GARP), is the first expressed on procyclic forms in the tsetse midgut and is of particular interest because it replaces the major surface coat molecule of bloodstream forms, the variant surface glycoprotein (VSG) that protects the parasite membrane, and is involved in antigenic variation. Unlike VSG, however, the function of GARP is not known, which necessarily limits our understanding of parasite survival in the tsetse. Toward establishing the function of GARP, we report its three-dimensional structure solved by iodide phasing to a resolution of 1.65 Å. An extended helical bundle structure displays an unexpected and significant degree of homology to the core structure of VSG, the only other major surface molecule of trypanosomes to be structurally characterized. Immunofluorescence microscopy and immunoaffinity-tandem mass spectrometry were used in conjunction with monoclonal antibodies to map both non-surface-disposed and surface epitopes. Collectively, these studies enabled us to derive a model describing the orientation and assembly of GARP on the surface of trypanosomes. The data presented here suggest the possible structure-function relationships involved in replacement of the bloodstream form VSG by GARP as trypanosomes differentiate in the tsetse vector after a blood meal.

Keywords: Antibodies, Epitope Mapping, Glycosylphosphatidylinositol Anchors, Parasitology, X-ray Crystallography, GARP, Trypanosoma congolense, Surface Protein

Introduction

African trypanosomes are protozoan parasites that cause serious disease in humans and their domestic animals in Sub-Saharan Africa. These parasites have influenced the development of Africa and continue to cause socioeconomic devastation, especially by infecting cattle, the mainstay of many smallholder farmers (1). Trypanosomes alternate between a mammalian host and an insect vector, the infamous tsetse (Glossina). In mammalian hosts, the trypanosomes live as bloodstream forms (BSFs)4 that are proficient at antigenic variation and host immune system evasion (2). Thus, no suitable vaccine candidates for trypanosomiasis have been identified after more than a century of research. In contrast, the trypanosome life cycle stages that exist in the tsetse vector do not undergo antigenic variation. This potentially makes the vector-occupying trypanosomes much better targets for control if strategies can be devised to disrupt their life cycle in the vector or to interfere with their transmission to mammalian hosts. The primary impediment to developing strategies for disruption of trypanosome life cycles in the tsetse is a lack of understanding of the molecular basis of trypanosome-tsetse interactions. In alternating between their mammalian hosts and tsetse vectors, trypanosomes are subject to dramatic changes in environment. Therefore, it is not surprising that their response, in terms of metabolism and surface architecture, is equally dramatic. Several major surface molecules have been identified on insect forms of Trypanosoma brucei ssp. (3) and on T. congolense (4–8). Although some of these molecules have been extensively studied, no functional role has been assigned to any of them.

All of the trypanosome surface proteins so far described are anchored to the surface membrane via glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors (9). During all life cycle stages, the trypanosomes are covered with a continuous dense monolayer of proteins and glycoproteins proposed to protect the parasite from the host immune system or from the proteolytic environment of the tsetse (10, 11). The parasite surface molecules expressed in the insect stages may play a role in parasite establishment, differentiation, maturation, and tropism (10, 11). In addition, a role for surface molecules in ligand-associated parasite vector signaling involved in programmed cell death has been proposed (12). Both BSFs and metacyclic forms of trypanosomes express a dense surface coat of variant surface glycoprotein (VSG) molecules (13) that shields non-variant underlying membrane proteins and protects them from host immune responses. These molecules are involved in antigenic variation, the well known immune evasion strategy evolved by African trypanosomes (2). Differentiation of BSFs into procyclic forms in the tsetse vector is characterized by replacement of the VSG coat with a more restricted set of tsetse-specific surface molecules (3). During this differentiation, at no time are parasites uncoated, as the insect form surface molecules are incorporated into the surface membrane as the VSG coat is replaced (14).

Trypanosoma species display different subsets of surface proteins. For example, T. brucei ssp. insect forms express the major surface glycoprotein EP and GPEET procyclins (15), whereas T. congolense insect forms express four major surface molecules: glutamic acid/alanine-rich protein (GARP) (4, 5), a protease-resistant surface molecule (6), a heptapeptide repeat protein (now considered the T. congolense procyclin) (7), and congolense epimastigote-specific protein (found exclusively on epimastigote forms in the tsetse mouthparts) (8). All of these molecules are surface-orientated, immunodominant, and highly charged. GARP is particularly interesting, as its expression coincides with the loss and gain of VSG in the tsetse vector. GARP is expressed by early procyclic forms in the tsetse midgut as VSG is replaced (6) and is absent in established procyclic midgut forms (6), where the T. congolense heptapeptide repeat protein procyclin is predominant (7). GARP is also strongly expressed by epimastigotes in tsetse mouthparts (6) and is lost during replacement by VSG molecules during differentiation to metacyclic forms.

Although GARP shows no sequence similarity to VSG molecules, it is tempting to speculate that its coexpression may mitigate the loss of VSG with respect to protecting the parasite membrane during differentiation. VSG molecules are well known to protect bloodstream trypanosomes from host antibody responses; however, the function of GARP is not known, although it has been hypothesized that it serves to protect the parasite membrane molecules from digestion enzymes in the tsetse midgut or to be involved in parasite differentiation and tropism within the tsetse (4, 10, 11). A requirement of this prediction is that GARP and VSG share a high degree of structural complementarity and that GARP is appropriately spatially oriented on the parasite cell surface. To address these possibilities, we present a detailed structural, immunofluorescence, and epitope mapping characterization of GARP. Collectively, the data offer a rare insight into the possible function of a trypanosome surface protein.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

GARP Cloning, Protein Production, and Purification

The amplified garp gene (mature N terminus to glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor site) from T. congolense was amplified from a cDNA expression library of strain IL 3000 (16) and cloned in pGEX4T-1 with forward primer 5′-GGATCC CAG AGC GTT CCC CCA AAG GT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GAATTC GGC CTT CTC CGC CTC GTA CT-3′. The PCR product was cloned using BamHI and EcoRI in frame with an N-terminal GST tag to facilitate purification. Sequence analysis of several clones revealed a limited number of polymorphisms, and a prominently isolated clone was selected for protein production. The GARP-GST fusion protein was produced recombinantly in Escherichia coli BL21 cells grown at 30 °C in autoinduction medium (Invitrogen). Following 24 h of growth, the cells were harvested, and the pellet was resuspended in buffer A (20 mm HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) and 150 mm NaCl) and lysed in a French press. The insoluble material was removed by centrifugation, and the soluble fraction was applied to a gravity flow glutathione-Sepharose 4B column (GE Healthcare). Following several washes, GARP was eluted with 10 mm reduced glutathione, and the GST tag was subsequently removed by thrombin cleavage. Additional FPLC purification steps included size exclusion (buffer A) and anion exchange (loading buffer: 20 mm HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) and 10 mm NaCl; elution buffer: 20 mm HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) and 500 mm NaCl) chromatography. The purity of GARP was assessed at each stage by SDS-PAGE, and protein concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm with a calculated extinction coefficient of 0.011 m−1 cm−1.

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Processing

Crystallization trials with purified recombinant GARP (rGARP) in buffer A were set with Index screen (Hampton Research) in 96-well sitting drop plates at 18 °C. The final drops consisted of 0.6 μl of rGARP at 35 mg/ml with 0.6 μl of reservoir solution and were equilibrated against 100 μl of reservoir solution. Diffraction quality crystals grew overnight in 12.5% polyethylene glycol 1500. A single crystal was looped, cryopreserved in mother liquor supplemented with 12.5% glycerol and 0.5 m sodium iodide for 50 s, and flash-cooled to 100 K directly in the cryostream. Diffraction data were collected on a Rigaku R-AXIS IV++ imaging plate area detector coupled to an MM-002 x-ray generator with Osmic Blue optics and an Oxford Cryostream 700 and processed with d*trek (17). Data collection and processing statistics are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell. r.m.s.d., root mean square deviation.

| Data collection and processing | |

| Space group | P1 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 36.18, 37.79, 40.68 |

| α, β, γ | 106.17°, 111.74°, 99.50° |

| Wavelength | 1.54180 |

| Resolution (Å) | 34.62-1.65 (1.71-1.65) |

| Measured reflections | 161,401 |

| Unique reflections | 20,523 |

| Redundancy | 7.86 (6.85) |

| Completeness (%) | 93.1 (89.0) |

| I/σ〈I〉 | 10.9 (3.5) |

| Rmergea | 0.087 (0.450) |

| Phasing statistics | |

| Phasing power | 0.870 |

| Figure of merit | 0.282 |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 34.62-1.65 (1.71-1.65) |

| Rworkb | 0.199 (0.334) |

| Rfreec | 0.251 (0.381) |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 1353 |

| Solvent | 257 |

| Iodide | 4 |

| Glycerol | 6 |

| B-values | |

| Protein (Å2) | 21.09 |

| Solvent (Å2) | 32.95 |

| Iodide (Å2) | 25.78 |

| Glycerol (Å2) | 21.51 |

| r.m.s.d. from ideality | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.015 |

| Bond angles | 1.402° |

| Ramachandran statistics (%) | |

| Most favored | 99.44 |

| Allowed | 0.56 |

| Disallowed | 0.0 |

a Rmerge = ΣhklΣi|Ihkl,i − [Ihkl]|/ΣhklΣiIhkl,i, where [Ihkl] is the average of symmetry-related observations of a unique reflection.

b Rwork = Σ|Fo − Fc|/ΣFo, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

c Rfree is R using 5% of reflections randomly chosen and omitted from refinement.

Phasing, Model Building, and Refinement

A total of four iodide sites were identified and refined using autoSHARP (18). Automated model building with ARP/Warp (19) was used to build and register ∼80% of the sequence. The remaining structure was built manually in COOT (20) and iteratively refined with REFMAC (21). All solvent atoms were inspected manually before deposition. Stereochemical analysis was performed using PROCHECK and SFCHECK in CCP4 (22). Overall, 5% of the reflections were set aside for calculation of Rfree. Phasing and refinement statistics are presented in Table 1.

Production and Selection of Monoclonal Antibodies

A BALB/c mouse (female, 8 weeks old) was immunized with rGARP over a 4-month period. Each injection contained 25 μg of rGARP. A priming injection in Freund's complete adjuvant was followed by two boosts in incomplete adjuvant and a final intravenous injection without adjuvant. Three days following the last injection, the mouse was killed, and the spleen was removed for cell fusion. Single-step hypoxanthine/aminopterin/thymidine selection and cloning of hybridomas were performed using the ClonaCell®-HY system (STEMCELL Technologies Inc., Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada). Following a 10-day incubation, 1000 hybridoma clones were picked and grown in wells of 96-well tissue culture microplates in 200 μl of clone picking medium as described by the manufacturer. Three days later, the hybridoma tissue culture supernatants were screened by indirect ELISA using 1.0 μg of rGARP as antigen and dried onto ELISA plates as described (23). Selected mAbs were tested by immunoblotting on rGARP and trypanosome lysates (4) and by immunofluorescence microscopy (24) on both living and acetone-permeabilized T. congolense IL 3000 procyclic culture forms (PCFs) and epimastigote forms (EMFs) (grown in vitro) and T. congolense 1/148 parasites taken directly from infected tsetse (in vivo) as described (25). Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) and anti-mouse IgM (μ-chain) secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) were used to detect the selected mAbs. Parasites were observed using a Leica DM6000B microscope fitted with an epifluorescence attachment and an oil immersion 100× Neofluor objective.

Trypanosomes

T. congolense IL 3000 (16) PCFs and EMFs were grown in vitro as described (4). T. congolense 1/148 BSFs and insect forms (27) were generously provided by Dr. Lee Haines (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine). T. brucei brucei 427 PCFs (26) and Trypanosoma simiae PCFs (26) were grown as described previously.

Identification of mAb Epitopes on rGARP

Epitope mapping was performed using immunoaffinity-mass spectrometry. Fifty μg of rGARP WAS initially concentrated by precipitation at 4 °C overnight in 9 volumes of ice-cold acetone. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the rGARP pellet was resolubilized in 30 μl of 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate and 6 m urea for trypsin digestion or in 30 μl of 25 mm ammonium carbonate (pH 7.8) for Glu-C digestion. rGARP samples were reduced with 30 μl of 10 mm DTT for 45 min at 37 °C and alkylated with 30 μl of 40 mm iodoacetamide for 45 min at 37 °C in the dark. Proteolysis of rGARP was performed by overnight digestion at 37 °C with trypsin (20 ng/μl stock, sequencing-grade porcine trypsin, Promega, Madison, WI) or at 24 °C with Glu-C (1 μg/μl stock, MS-grade, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). An enzyme/protein ratio of 1:20 was used with both enzymes. To stop digestion, a 1× final concentration of protease inhibitor mixture was used (Set V, EDTA-free, Calbiochem), and the digest mixture was diluted with PBS to a final concentration of 0.2 μg of rGARP/μl. Peptides were immunoenriched from the digests using mAb-coupled magnetic beads (goat anti-mouse IgG Dynabeads, Invitrogen Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway). Beads were initially washed three times with 500 μl of PBS, followed by incubation with 1 ml of hybridoma tissue culture supernatant overnight at 4 °C. The mAb-coupled beads were washed three times with 1 ml of PBS and resuspended in 25 μl of PBS and 0.1% Tween 20 just prior to use. For each peptide capture reaction, 50 μl of digested rGARP (0.2 μg/μl, ∼10 μg) was added to 25 μl of mAb-coated Dynabeads. Capture reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h with shaking, after which the beads were magnetically captured and washed with PBS. Non-bound, non-epitope peptides were saved to allow comparison with captured peptides. Elution of bound peptides was performed by incubating the immunoaffinity beads in 50 μl of 5% acetic acid for 5 min at 20 °C.

MALDI-TOF MS

Captured and non-captured peptides from trypsin and Glu-C digests were desalted with C18 ZipTips. For each sample, 1 μl of the desalted peptide mixture was mixed (1:1) with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid and spotted onto a Voyager 100-position stainless steel MALDI plate (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Calmix 2 internal standards consisting of angiotensin-1 (1296.6853), ACTH(1–17) clip (2093.0867), and ACTH(18–39) clip (2465.1989) were used to calibrate the Voyager prior to analysis of samples. An Applied Biosystems Voyager DE-STR mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems) running in delayed extraction reflectron mode was used to acquire MALDI-TOF data. For in silico digestion, the rGARP protein sequence was submitted to MS digest (ProteinProspector software), and peptide masses were compared with the in-solution digests. Captured peptides were also detected and processed by MS/MS to confirm sequence. Peptides were spotted onto a 384 OptiT MALDI plate and analyzed on an Applied Biosystems/MDS SCIEX 4800 MALDI TOF/TOF analyzer. Peptides were identified by database searching of MS/MS spectra using GPS ExplorerTM Version 3.5 software. The immunoaffinity-MS experiments to localize the mAb epitopes were performed twice as complete experimental replicates.

RESULTS

Size Exclusion Chromatogram Suggests a Dimeric Assembly or Non-globular Shape for GARP

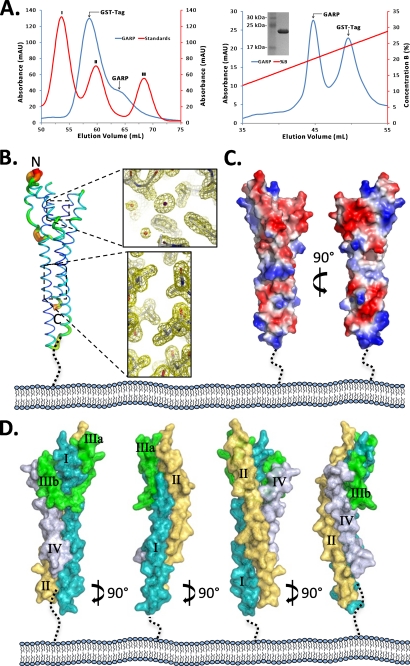

T. congolense GARP was recombinantly produced in E. coli (rGARP) and initially purified using GST affinity chromatography, followed by thrombin digestion to remove the GST tag. A size exclusion chromatogram (Fig. 1A, left panel) of the digested protein revealed a small absorbance for GARP consistent with the lack of tryptophan residues and a theoretical extinction coefficient of 0.014 m−1 cm−1. Based on a linear regression fit with molecular mass standards, rGARP eluted consistent with a protein of ∼36 kDa, suggesting either a rGARP dimer (the theoretical molecular mass of the rGARP monomer is 19.5 kDa) or a distinct non-globular shape. A final purification step incorporating anion exchange chromatography (Fig. 1A, right panel) successfully removed residual contaminating GST and resulted in sufficiently pure rGARP for crystallization trials.

FIGURE 1.

GARP adopts an extended helical structure. A, left panel, Superdex 200 size exclusion chromatogram of rGARP (blue curve). The protein standards used were conalbumin (75 kDa; peak I), ovalbumin (43 kDa; peak II), and carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa; peak III). Right panel, anion exchange chromatogram showing the separation of rGARP from contaminating GST. Inset, SDS-PAGE of purified rGARP. mAU, milli-absorbance units. B, B-factor putty model of the GARP ectodomain displayed in the predicted orientation with respect to the parasite cell surface. Ordered regions are shown in blue and thin ribbons, whereas flexible regions are displayed in red and larger diameter tubes. Insets, 2Fo − Fc σA weighted electron density maps at 1.2σ showing one of the iodide sites (upper inset) and the ordered interhelical interface (lower inset). C, electrostatic surface representation of rGARP reveals a broad distribution of acidic and basic patches along the entire length of the helical structure. D, surface representation of the rGARP ectodomain highlighting the intimate assembly of extended helices I (teal), II (gold), and IV (gray) and the role of the helix (IIIa)-loop-helix (IIIb) (green) in organizing the C-terminal portion of the ectodomain.

GARP Adopts an Extended Helical Bundle Structure

rGARP crystallized as a monomer in a P1 unit cell consistent with an interpretation of the initial size exclusion profile for rGARP as adopting a non-globular shape rather than a dimeric assembly. Attempts to solve the structure of GARP by molecular replacement were unsuccessful, as no models of sufficient homology were identified by sequence alignment. Ultimately, the structure of GARP was solved by iodide single anomalous dispersion phasing, and the final model was refined to a resolution of 1.65 Å. The final model is highly ordered with clear electron density and low B-factors for all residues except Lys-150, positioned on a short surface loop spatially located near the N terminus (Fig. 1B). It is noteworthy that an unpaired cysteine (Cys-148), positioned on the same surface loop as Lys-150, displays clear electron density for an oxidized sulfur, which explains why no disulfide-mediated multimers were observed during purification.

Overall, the GARP ectodomain extends ∼90 Å in height and, on average, 25 Å in width with respect to its predicted orientation to the membrane. The surface of GARP is highly polar, with both positively and negatively charged patches broadly distributed over the length of the ectodomain (Fig. 1C). The scaffold of GARP is defined primarily by a core of extended twisted helices with a smaller helical bundle packed onto the predicted membrane-distal N-terminal end (Fig. 1, C and D). Helix I extends from Lys-40 through Lys-92 and adopts an approximate 40° bend at Ala-56. A short loop connects helices I and II (Val-96–Thr-147), which are similar in size and adopt a similar angular distortion at Ser-131. Connecting helix II to helix IV is a small helical bundle composed of helices IIIa (Glu-153–Lys-161) and IIIb (Ser-171–Leu-174), which are separated by a 10-residue loop. Despite adopting a random coil structure, this loop is well ordered with low B-factors and serves to position helices IIIa and IIIb on opposite sides of helix I, creating a tightly packed five-helical bundle head group of GARP. Helix IV (Ala-189–Ala-223) completes the GARP ectodomain structure and results in the C terminus positioned at the opposite end of the GARP ectodomain relative to the N terminus.

Monoclonal Antibodies 2-D7 and 4-B7 Recognize Recombinant and Native Forms of GARP

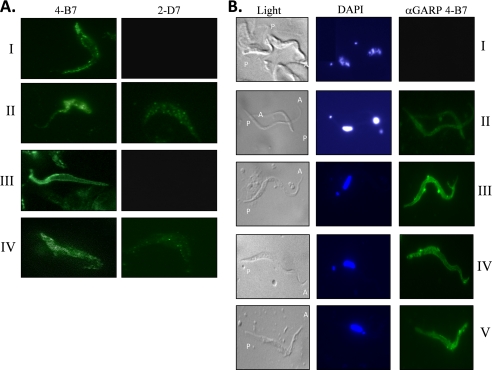

A total of 48 hybridomas were selected based on binding to rGARP in ELISA. Of the 48 mAbs, 15 were also positive in immunoblots on rGARP, thus ostensibly bound linear epitopes on the denatured polypeptide. To evaluate the ability of the mAbs to react with GARP in the presence of post-translational modifications, immunoblotting was performed using proteins separated from lysates of PCFs from different trypanosome species. Of the 15 mAbs, five reacted with “natural” GARP protein in T. congolense PCFs and one mAb (2-D7) reacted with a protein in the PCF of the related T. simiae. None of the 15 mAbs reacted with antigens of T. brucei brucei PCFs (immunoblot data not shown). Flow cytometry and immunofluorescence microscopy on live T. congolense PCFs were then used to determine the surface reactivity of all six selected mAbs. Only one mAb (4-B7) showed surface fluorescence. Thus, although the epitope recognized by mAb 4-B7 appears to be a linear sequence as determined by immunoblotting on denatured rGARP, it is a surface-disposed epitope on GARP in situ on the trypanosome surface.

Based on binding patterns in immunoblots and surface immunoreactivity on live cells, mAb 2-D7 (a non-surface binder) and surface-binding mAb 4-B7 were selected for more detailed analysis. Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed on live and acetone-permeabilized T. congolense insect stages grown in vitro as culture forms (Fig. 2A) and on parasites harvested from infected tsetse (Fig. 2B). mAb 4-B7 clearly bound to the surface of both live PCFs and EMFs and to acetone-permeabilized parasites (Fig. 2A). Although mAb 2-D7 did not recognize GARP on live PCFs and EMFs, it was able to react weakly when the cells were acetone-permeabilized, indicating that the surface coat had been perturbed, allowing access to the antibody (Fig. 2B). This suggests that the mAb 2-D7 epitope may be concealed by tight packing of GARP on the parasite cell surface.

FIGURE 2.

Immunofluorescence analysis of anti-GARP mAbs on trypanosomes grown in vitro and in vivo in infected tsetse. A, T. congolense IL 3000 grown in vitro. Row I, live PCFs; row II, acetone-fixed PCFs; row III, live EMFs; row IV, acetone-fixed EMFs. B, T. congolense 1/148 harvested from rats or infected tsetse. Row I, BSFs isolated from infected rats; row II, PCFs isolated from midguts of infected tsetse after 10.5 days; row III, PCFs isolated from midguts of infected tsetse after 25 days; row IV, proventricular forms isolated from the tsetse proventriculus; row V, EMFs isolated from tsetse mouthparts. Trypanosomes were simultaneously labeled with anti-GARP mAb 4-B7 and the DNA-binding dye DAPI. The posterior (P) and anterior (A) ends of the trypanosomes are indicated. With both in vitro and in vivo grown parasites, undiluted hybridoma tissue culture supernatants containing primary antibodies were used as the primary antibody, followed by a 1:50 dilution of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG/M secondary antibody.

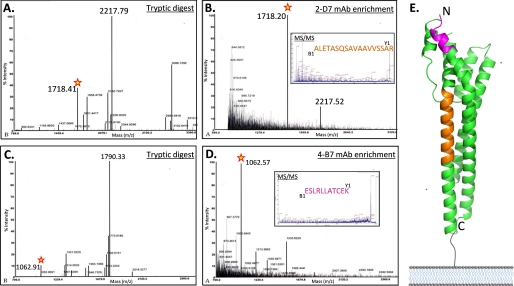

Identification and Localization of Anti-GARP mAb 2-D7 and 4-B7 Epitopes on the GARP Crystal Structure

To explicitly define the regions of GARP recognized by mAbs 4-B7 and 2-D7, we proceeded to map the epitopes by mass spectrometry of peptides immunoenriched from proteolytic digests of rGARP (Fig. 3). We theorized that accurate epitope mapping of mAbs 4-B7 and 2-D7 would provide valuable information as to the orientation and packing of GARP on the trypanosome surface membrane.

FIGURE 3.

MALDI-TOF mass spectra of rGARP peptides before and after immunoenrichment using monoclonal antibodies. For the purposes of clarity, only the major peaks are highlighted. A, mass spectrum of the rGARP trypsin digest. B, mAb 2-D7 immunoenrichment of a monoisotopic peptide mass of 1718 Da from the trypsin digest (red star). Inset, MS/MS sequencing of the enriched 1718-Da peptide (56ALETASQSAVAAVVSSAR73, orange). C, mass spectrum of the rGARP Glu-C digest. D, mAb 4-B7 immunoenrichment of a monoisotopic mass of 1062 Da. Inset, MS/MS sequencing of the enriched 1062-Da peptide (141SLRLLATCE149, purple). E, GARP crystal structure showing the location of surface-exposed (mAb 4-B7) and buried (mAb 2-D7) epitopes.

Peptides were enriched from both trypsin (Fig. 3A) and Glu-C (Fig. 3C) digests of rGARP using mAbs 2-D7 (Fig. 3B) and 4-B7 (Fig. 3D) coupled to magnetic beads, respectively. mAb 2-D7, which recognizes a non-exposed GARP epitope (Fig. 2, A and B), selectively enriched a monoisotopic peptide mass of 1718 Da from the trypsin digest (Fig. 3B). Based on the in silico trypsin digest of the GARP sequence, the sequence of the 1718-Da peptide was 56ALETASQSAVAAVVSSAR73. The same mAb, 2-D7, did not enrich any peptides from a Glu-C digest of rGARP (data not shown). It is likely that the 1718-Da peptide enriched by mAb 2-D7 from the trypsin digest was cleaved by Glu-C at Glu (underlined) in the sequence 56ALETASQSAVAAVVSSAR73.

When rGARP was digested with Glu-C and the released peptides were incubated with mAb 4-B7, a peptide with a monoisotopic mass of 1062 Da was selectively enriched (Fig. 3C). Based on the in silico Glu-C digest of rGARP, the corresponding amino acid sequence for the 1062-Da peptide was 141SLRLLATCE149. In contrast, mAb 4-B7 did not enrich any peptides from trypsin-digested rGARP. This is not surprising because the peptide containing the presumed epitope has an internal tryptic cleavage site (Arg, underlined) and would be cleaved in 141SLRLLATCE149, thereby destroying the epitope. MALDI-TOF MS/MS was used to confirm the amino acid sequences of the immunoenriched 1062- and 1718-Da peptides (Fig. 3, B and C, insets).

To display the spatial relationships of the identified peptides on the protein surface, the peptides were mapped onto the GARP ectodomain structure (Fig. 3E). Interestingly, the non-exposed epitope recognized by mAb 2-D7 (Fig. 3E, orange) is found approximately midway along helix I, where, if the GARP molecules were tightly packed on the trypanosome membrane, the 2-D7 epitope would be inaccessible to antibodies. In contrast, the epitope recognized by mAb 4-B7 (Fig. 3E, purple) is located near the tip of the GARP polypeptide at the C-terminal end of helix II and distal to the parasite membrane. Thus, the mAb 4-B7 is unshielded by other GARP molecules on the parasite cell surface and readily accessible to the antibody.

DISCUSSION

The Structure of GARP Allows Tight Intramolecular Packing on the Trypanosome Cell Surface

GARP is predicted to serve a key role in protecting the parasite membrane from digestive enzymes, antibodies, and complement in the tsetse midgut (10, 11). This is supported by immunogold electron microscopy studies in which it was shown that GARP is densely packed on the cell surface of T. congolense (5). We have now established a structural rationale for this latter observation that supports the prediction that GARP would form a rather dense protective shield. The GARP ectodomain adopts a highly ordered, extended α-helical structure that is consistent with the ability to pack tightly on the surface of the parasite.

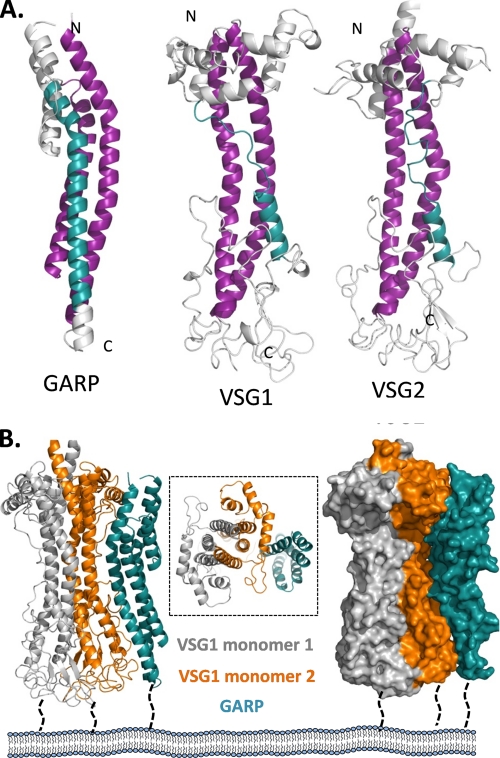

Does the Structure of GARP Allow Tight Intramolecular Packing with VSG on the Trypanosome Cell Surface?

On the basis of the observations that the structure of GARP is amenable to self-assembly to form a dense layer on the parasite cell surface, we explored whether GARP displays structural complementarity to VSG, the only other structurally characterized trypanosome major surface protein (28). Intriguingly, a structural comparison of GARP with two different VSGs revealed a complementary core of twisted α-helices (Fig. 4A). A pair of extended bent helices (Fig. 4A, purple) anchor the core and form a platform on which a third helix (teal) packs. This third helix is less well conserved, as it is composed of both a helical and loop portion in the VSG structures. Collectively, the similarity between the three protein structures demonstrates a core template indicative of conserved function.

FIGURE 4.

Structural complementarity between GARP and VSG. A, secondary structure representation of GARP, VSG1 (Protein Data Bank code 1VSG), and VSG2 (code 2VSG), with core helices shown in purple and teal. B, proposed model for GARP-VSG assembly on the parasite cell surface. Secondary and surface representations of the VSG1 monomers (gray and orange) are manually docked with GARP (teal), revealing the structural complementarity. Inset, view looking down at the parasite cell surface showing the conserved twisted α-helical structures of GARP and VSG.

The observation that GARP shares a general shape with VSG molecules suggested that VSG and GARP could potentially form a continuous surface coat. This feature would be particularly valuable to the trypanosome during the VSG loss and GARP gain that occur during differentiation from BSFs to procyclic forms in the tsetse midgut and again when GARP is replaced by VSG upon differentiation from epimastigote forms to metacyclic forms in the tsetse mouthparts. Tight packing of surface coat molecules on the trypanosome would aid parasite survival because at no time would their surface membrane be unshielded. Indeed, studies on T. brucei brucei clearly demonstrated that during differentiation from BSFs to procyclic forms, as VSG molecules were lost from the parasite surface, they were replaced by the EP procyclins such that at no time were there trypanosomes that were not coated (14).

To assess the degree of structural complementarity, the GARP ectodomain structure was manually docked against the VSG1 dimer (Fig. 4B). Both a secondary structure and surface representation reveal the potential for intimate packing between these surface proteins. Furthermore, a top-down view illustrates the homology of the shared twisted helical bundles. The main structural differences are localized at the extreme ends of the protein where bundles of helices or loops cap the core helical structure. In VSGs, these are highly variable sequences involved in antigenic variation. There are no “cap-like” structures on GARP, suggesting that the proteins may serve primarily as a tight self-associating barrier on the parasite cell surface.

The major surface molecules so far described on T. congolense insect forms appear to be differentially expressed in different compartments during transit though their tsetse vector. In light of our analysis of GARP, it will be interesting to determine the crystal structures of the T. congolense procyclin, the T. congolense heptapeptide repeat protein, and congolense epimastigote-specific protein, as they may be predicted to have structures allowing functionally interesting relationships with the other major molecules on the parasite surface.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Lee Haines for generously providing trypanosomes from infected tsetse and for preparing microscope slides.

This work was supported in part by separate Discovery Grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (to M. J. B. and T. W. P.).

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2Y44) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- BSF

- bloodstream form

- VSG

- variant surface glycoprotein

- GARP

- glutamic acid/alanine-rich protein

- rGARP

- recombinant GARP

- PCF

- procyclic culture form

- EMF

- epimastigote form.

REFERENCES

- 1. Swallow B. M. (2000) PAAT Technical and Scientific Series 2, Rome, FAO/WHO/IAEA/OAU-IBAR [Google Scholar]

- 2. Donelson J. E. (2003) Acta Trop. 85, 391–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roditi I., Furger A., Ruepp S., Schürch N., Bütikofer P. (1998) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 91, 117–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beecroft R. P., Roditi I., Pearson T. W. (1993) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 61, 285–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bayne R. A., Kilbride E. A., Lainson F. A., Tetley L., Barry J. D. (1993) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 61, 295–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bütikofer P., Vassella E., Boschung M., Renggli C. K., Brun R., Pearson T. W., Roditi I. (2002) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 119, 7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Utz S., Roditi I., Kunz Renggli C., Almeida I. C., Acosta-Serrano A., Bütikofer P. (2006) Eukaryot. Cell. 5, 1430–1440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sakurai T., Sugimoto C., Inoue N. (2008) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 161, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferguson M. A. J. (1999) J. Cell Sci. 112, 2799–2809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roditi I., Pearson T. W. (1990) Parasitol. Today 6, 79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stebeck C. E., Pearson T. W. (1994) Exp. Parasitol. 78, 432–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pearson T. W., Beecroft R. P., Welburn S. C., Ruepp S., Roditi I., Hwa K. Y., Englund P. T., Wells C. W., Murphy N. B. (2000) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 111, 333–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vickerman K. (1969) J. Cell Sci. 5, 163–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roditi I., Schwarz H., Pearson T. W., Beecroft R. P., Liu M. K., Richardson J. P., Bühring H. J., Pleiss J., Bülow R., Williams R. O., Overath P. (1989) J. Cell Biol. 108, 737–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roditi I., Clayton C. (1999) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 103, 99–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fish W. R., Muriuki C. W., Grab D. J., Lonsdale-Eccles J. D. (1989) Biochemistry 28, 5415–5421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pflugrath J. W. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55, 1718–1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vonrhein C., Blanc E., Roversi P., Bricogne G. (2007) Methods Mol. Biol. 364, 215–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perrakis A., Morris R., Lamzin V. S. (1999) Nature Struct. Biol. 6, 458–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Collaborative Computational Project Number 4 (1994) Acta Crystallog. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tolson D. L., Turco S. J., Beecroft R. P., Pearson T. W. (1989) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 35, 109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tolson D. L., Turco S. J., Pearson T. W. (1990) Infect. Immun. 58, 3500–3507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haines L. R., Lehane S. M., Pearson T. W., Lehane M. J. (2010) PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cross G. A., Manning J. C. (1973) Parasitology 67, 315–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zweygarth E., Röttcher D. (1987) Parasitol. Res. 73, 479–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Freymann D., Down J., Carrington M., Roditi I., Turner M., Wiley D. J. (1990) J. Mol. Biol. 216, 141–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]