Abstract

Background

In higher plants, the inhibition of photosynthetic capacity under drought is attributable to stomatal and non-stomatal (i.e., photochemical and biochemical) effects. In particular, a disruption of photosynthetic metabolism and Rubisco regulation can be observed. Several studies reported reduced expression of the RBCS genes, which encode the Rubisco small subunit, under water stress.

Results

Expression of the RBCS1 gene was analysed in the allopolyploid context of C. arabica, which originates from a natural cross between the C. canephora and C. eugenioides species. Our study revealed the existence of two homeologous RBCS1 genes in C. arabica: one carried by the C. canephora sub-genome (called CaCc) and the other carried by the C. eugenioides sub-genome (called CaCe). Using specific primer pairs for each homeolog, expression studies revealed that CaCe was expressed in C. eugenioides and C. arabica but was undetectable in C. canephora. On the other hand, CaCc was expressed in C. canephora but almost completely silenced in non-introgressed ("pure") genotypes of C. arabica. However, enhanced CaCc expression was observed in most C. arabica cultivars with introgressed C. canephora genome. In addition, total RBCS1 expression was higher for C. arabica cultivars that had recently introgressed C. canephora genome than for "pure" cultivars. For both species, water stress led to an important decrease in the abundance of RBCS1 transcripts. This was observed for plants grown in either greenhouse or field conditions under severe or moderate drought. However, this reduction of RBCS1 gene expression was not accompanied by a decrease in the corresponding protein in the leaves of C. canephora subjected to water withdrawal. In that case, the amount of RBCS1 was even higher under drought than under unstressed (irrigated) conditions, which suggests great stability of RBCS1 under adverse water conditions. On the other hand, for C. arabica, high nocturnal expression of RBCS1 could also explain the accumulation of the RBCS1 protein under water stress. Altogether, the results presented here suggest that the content of RBCS was not responsible for the loss of photosynthetic capacity that is commonly observed in water-stressed coffee plants.

Conclusion

We showed that the CaCe homeolog was expressed in C. eugenioides and non-introgressed ("pure") genotypes of C. arabica but that it was undetectable in C. canephora. On the other hand, the CaCc homeolog was expressed in C. canephora but highly repressed in C. arabica. Expression of the CaCc homeolog was enhanced in C. arabica cultivars that experienced recent introgression with C. canephora. For both C. canephora and C. arabica species, total RBCS1 gene expression was highly reduced with WS. Unexpectedly, the accumulation of RBCS1 protein was observed in the leaves of C. canephora under WS, possibly coming from nocturnal RBCS1 expression. These results suggest that the increase in the amount of RBCS1 protein could contribute to the antioxidative function of photorespiration in water-stressed coffee plants.

Background

With a world production of 134 million bags of beans in 2010 http://www.ico.org, coffee is the most important agricultural commodity worldwide and a source of income for many developing tropical countries [1]. In the genus Coffea, two species are responsible for almost all coffee bean production: Coffea canephora and Coffea arabica, which contribute approximately 30 and 70% of worldwide production, respectively [2]. C. canephora is a diploid (2n = 2x = 22) and allogamous Coffea species. On the other hand, C. arabica is an amphidiploid (allotetraploid, 2n = 4x = 44), which comes from a natural hybridisation estimated to have taken place more than 100,000 years ago between the ancestors of present-day C. canephora and C. eugenioides [3]. In this context, the transcriptome of C. arabica is a mixture of homeologous genes expressed from these two sub-genomes [4]. Aside from the pure "Arabica" varieties, C. arabica cultivars recently introgressed with C. canephora genome have been selected in order to take advantage of available C. canephora's disease-resistant genes. Natural and recent interspecific (C. arabica x C. canephora) Timor Hybrids as well as controlled interspecific crosses provided the progenitors for these introgressed C. arabica varieties [5].

Coffee production is subjected to regular oscillations explained mainly by the natural biennial cycle but also by the adverse effects of climatic conditions. Among them, drought and high temperature are key factors affecting coffee plant development and production [6,7]. If severe drought periods can lead to plant death, moderate drought periods are also very damaging to coffee growers by affecting flowering, bean development and, consequently, coffee production. In addition, large variations in rainfall and temperature also increase bean defects, modify bean biochemical composition and the final quality of the beverage [8-11]. As a result of global climate change, periods of drought may become more pronounced, and the sustainability of total production, productivity and coffee quality may become more difficult to maintain [12].

The primary effects of water stress (WS) on physiological and biochemical processes in plants have been extensively discussed [13-16]. They are attributable to various processes, including diffusional (stomatal and mesophyllian resistances to the diffusion of CO2), photochemical (regulation of light harvest and electron transport) and/or biochemical processes (e.g., regulation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase content or activity and regulation of the Calvin cycle through exports of assimilates). Stomatal closure is one of the earliest responses to short-term soil drying, therefore limiting water loss and net carbon assimilation (A) by photosynthesis. The decrease of photosynthesis under WS can come from CO2 limitation mediated by stomatal closure or by a direct effect on the photosynthetic capacity of chloroplasts. Independently of the nature of this reduction, the intensity of the intercepted irradiance can greatly exceed the irradiance necessary to saturate photosynthesis. As CO2 assimilation precedes inactivation of electron transfer reactions, an excess of reducing power is frequently generated in water-stressed plants [17]. Thus, this excess can be used to reduce the molecular oxygen leading to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and causing photooxidative damage [18]. Under prolonged drought stress, reduced growth, reduced leaf area and altered assimilate partitioning among tree organs seems to be responsible for decreased crop yield [19]. In C3 plants, the key photosynthetic enzyme is the Rubisco (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, EC 4.1.1.39), which is responsible for CO2 fixation and photorespiration [20]. This enzyme is localised in the chloroplast stroma and accounts for approximately 30-60% of the total soluble protein in plants. Rubisco also constitutes a large pool of stored leaf nitrogen that can be quickly remobilised under stress and senescence [21,22]. In higher plants, the Rubisco holoenzyme is composed of large (RBCL) and small (RBCS) subunits encoded respectively by the unique chloroplastic RBCL gene and the small RBCS multigene family located in the nucleus [23]. In fact, potential Rubisco activity is determined by the amount of Rubisco protein, which in turn is determined by the relative rate of biosynthesis and degradation. These processes are regulated by gene expression, mRNA stability, polypeptide synthesis, post-translational modification, assembly of subunits into an active holoenzyme, and various factors that impact upon protein degradation [24-26].

Numerous studies have shown that RBCS transcripts accumulate differentially in response to light intensity or tissue development [for a review, see [27]]. This raises the possibility that RBCS subunits may regulate the structure or function of Rubisco [28]. At the molecular level, drought stress suppresses the expression of many photosynthetic genes including the RBCS genes [29-33]. In contrast, transcripts encoding enzymes of the pentose phosphate and glycolytic pathway (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and pyruvate kinase) were induced during drought, suggesting that these pathways are used for the production of reducing power in the absence of photosynthesis during stress [34]. Even if Rubisco inactivation contributes to the non-stomatal limitation of photosynthesis under drought stress [35,36], data demonstrated a Rubisco reduction in stressed plants [37-39]. This is in agreement with the observation that part of the biochemical limitation of the photosynthetic rate (A) during drought comes from Rubisco regeneration rather than from a decrease in Rubisco activity [40]. In that sense, the WS-induced decrease in Rubisco content may characterise a general stimulation of senescence and/or the specific degradation of this protein by oxidative processes [41]. However, other work has reported that the amount of Rubisco protein is poorly affected by moderate and even prolonged severe drought [42]. The mechanism by which Rubisco may be down-regulated due to tight binding inhibitors could be pivotal for the tolerance and recovery from stress [38]. Rubisco binding proteins that are able to stabilise Rubisco could also be related to drought tolerance [41,43], but their roles in the structure, function and regulation of RBCS subunits are poorly understood [28,44].

During the last decade, coffee breeding programs identified clones of C. canephora var. Conilon that presented differential responses to WS [45]. Physiological characteristics of these clones revealed differences in root depth, stomatal control of water use and long-term water use efficiencies (WUE), which were estimated through carbon isotope discrimination [for a review, see [7]]. Even if some coffee cultivars perform osmotic adjustment under water deficit stress [46], little is known about the mechanisms of drought stress tolerance in coffee trees [47]. When studying container-grown C. arabica L. plants for 120 days under three soil moisture regimes, Meinzer et al. [48] observed that the total leaf area of plants irrigated twice a week was one-half that of plants irrigated twice a day although their assimilation rates on a unit-leaf-area basis were nearly equal throughout the experiment. This suggests that the maintenance of nearly constant photosynthetic characteristics on a unit-leaf-area basis through the maintenance of a smaller total leaf area may constitute a major mode of adjustment to reduced soil moisture availability in coffee. Similar results were also reported for field-grown C. canephora [46].

The periodicity of coffee vegetative growth is also heavily dependent on several environmental factors, such as temperature, photoperiod, irradiance and water supply. Seasonal changes in vegetative growth and photosynthesis were previously reported for field-grown plants of C. arabica L. cv. Catuaí Vermelho [49]. In that case, the reduced growth period during the winter season was characterised by a decline in air temperature leading to a decrease in the net carbon assimilation rate (A) and leaf starch accumulation. This decrease in photosynthesis during the winter season is not likely to be due to stomatal limitation because gs (stomatal conductance) remains relatively high at the same time. Kanechi et al. [50] showed that low rates of photosynthesis were accompanied by a decreased content of Rubisco in coffee leaves exposed to prolonged WS. In another study, Kanechi et al. [51] also demonstrated that leaf photosynthesis in coffee plants exposed to rapid dehydration decreased as a consequence of non-stomatal limitation that was associated with the inhibition of Rubisco activity.

Regarding the importance of photosynthesis in controlling plant development and the lack of information concerning expression of genes coding for Rubisco subunits in coffee, here, we decided to first focus on the expression of RBCS1 genes encoding the small subunit of Rubisco. Using the recent advances in coffee genomics [52-57] and the CaRBCS1 cDNA available from C. arabica [58], our study aims to (i) identify the different coffee RBCS1 gene homeologs corresponding to the C. canephora and C. eugenioides ancestor sub-genomes of the amphidiploid C. arabica species, (ii) evaluate the expression of these alleles in different coffee genotypes and species with an emphasis on C. arabica cultivars with and without recent introgression from C. canephora and (iii) study the effects of different (moderate and severe) WS on RBCS1 expression in juvenile and adult C. canephora and C. arabica plants. Finally, RBCS1 expression was also studied at different times of the day and discussed in relation to the RBCS1 protein profiles observed under WS.

Results

Identification of coffee cDNA sequences coding for RBCS1 (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase small subunit)

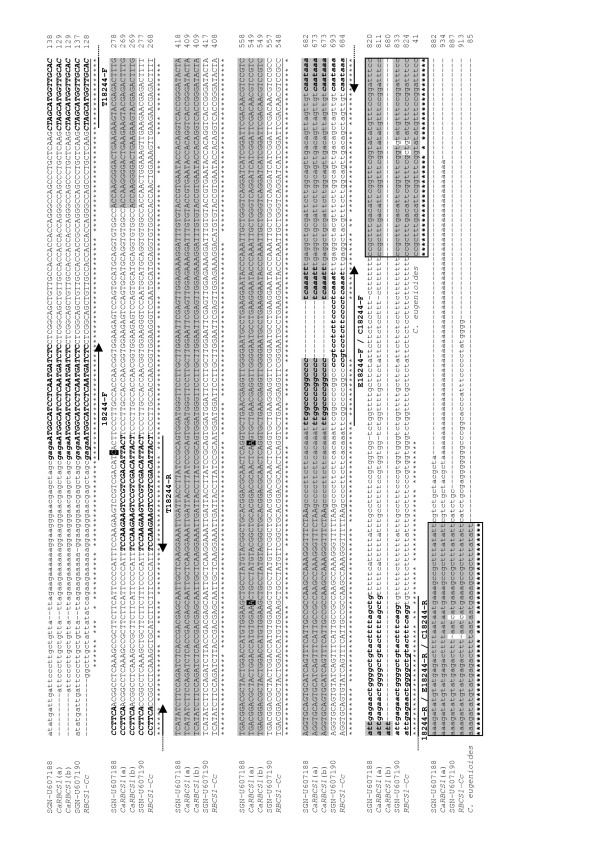

The use of the CaRBCS1 [GenBank:AJ419826] cDNA from C. arabica as a query sequence identified several similar sequences in the coffee databases, and they were aligned for comparison (Figure 1). The C. arabica unigene SGN-U607188 preferentially aligned with the CaRBCS1 cDNA and gene sequences already reported for this species, and it matched perfectly with the coding sequences of partial RBCS1 genes cloned from different genotypes of C. arabica [GenBank:DQ300266 to DQ300277; L.S. Ramirez, unpublished results]. On the other hand, the C. arabica unigene (SGN-U607190) was more identical to the C. canephora SGN-U617577 unigene than other C. arabica SGN-U607188 unigene. A single and short RBCS1 EST of C. eugenioides [4] was also aligned with these sequences. Notably, it was strictly identical with the CaRBCS1 and SGN-U607188 sequences from C. arabica but diverged by few bases with the unigenes SGN-U607190 and SGN-U617577 of C. canephora.

Figure 1.

Alignment of coffee RBCS1 nucleic sequences. Sequences of the CaRBCS1 cDNA [58] from C. arabica cv. Caturra (a) [Genbank:AJ419826] and of the corresponding gene (b) [GenBank:AJ419827] without introns, were aligned with the unigenes SGN-U607188, SGN-U607190 and RBCS1-Cc (identical to SGN-U617577 formed by the alignment of 145 reads found in leaf cDNA libraries from C. canephora) from the SOL genomic database [56] and with the unique RBCS1 homologous read of C. eugenioides [4]. The SGN-U607188 and SGN-U607190 unigenes were formed by the alignment of reads found in cDNA libraries from fruits and the leaves of C. arabica plants. The coding sequences of the partial RBCS1 genes from genotypes of C. arabica [Genbank:DQ300266 to DQ300277; L.S. Ramirez, unpublished results] that matched with CaRBCS1 sequences are underlined in grey, while base differences are boxed in black. The CcRBCS1 cDNA sequence [GenBank:FR728242, this work] corresponded to the underlined sequence of the SGN-U617577 unigene. For all the sequences, the coding sequence is in uppercase, and the 5' and 3' UTR regions are in lower case. Horizontal arrows as well as nucleotides in bold and italics indicate the primers (Table 1) used for qPCR reactions. The stars below the alignments indicate identical bases, and the nucleotides are numbered for each lane.

Within the RBCS1 protein-coding sequence, five bases differed between SGN-U607188 and SGN-U607190, but only three diverged between the sequences of C. arabica. The main difference between all of these sequences was found in their 3' untranslated (UTR) region by the presence of a 12-bp sequence (GTCCTCTTCCCC) localised 31 bp after the stop codon of the unigenes SGN-U607190 and SGN-U617577 of C. canephora, which was not observed in the CaRBCS1 gene and cDNA sequences. In addition, the C. arabica unigene SGN-U607190 was more related to the C. canephora unigene SGN-U617577 than to the previously-cloned CaRBCS1 cDNA.

RBCS1 cDNAs were sequenced from the Rubi (Mundo Novo x Catuaí) cultivar of C. arabica that did not recently introgress with C. canephora genomic DNA and clone 14 of C. canephora var. Conilon using primer pair 18244, which was designed to conserved RBCS1 cDNA regions of the two species. For the Rubi cultivar, the cDNA was strictly identical to the RBCS1 coding region of the CaRBCS1 gene [GenBank:AJ419827] and without detection of any single nucleotide polymorphisms (data not shown). On the other hand, the RBCS1 cDNA from C. canephora was strictly identical to the unigene SGN-U617577 (Figure 1). Altogether, these results confirmed those retrieved from the EST analysis, which demonstrated the existence of two homeologous genes of RBCS1 in C. arabica, one from the C. canephora sub-genome and another from the C. eugenioides sub-genome.

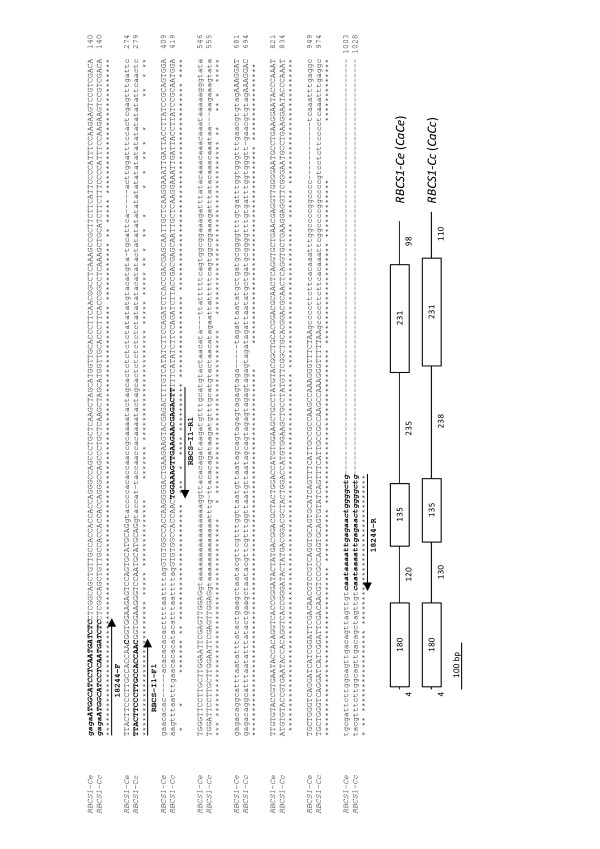

Cloning of the CcRBCS1 gene

The RBCS1 gene from C. canephora (called RBCS1-Cc or CaCc) was also cloned and sequenced (Figure 2). It shared 90% nucleotide identity with the CaRBCS1 gene from C. arabica that corresponds to the RBCS1 gene (called RBCS1-Ce or CaCe) of the C. eugenioides sub-genome. The two genes exhibited a similar structure and consisted of three exons and two introns. The sizes of the first and second introns were 120 bp and 235 bp for the CaCe allelic form and 130 bp and 238 bp for the CaCc allelic form, which therefore demonstrates inter-specific sequence polymorphisms. The nucleotide sequences differed by numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and several insertion and deletion (indels) events in the introns and the 3' UTR region. Regarding the introns, it is worth noting that those of the RBCS1-Cc gene were always slightly longer than those of the RBCS1-Ce gene.

Figure 2.

Alignment of the RBCS1 genes from C. arabica and C. canephora. The CaRBCS1 gene [GenBank:AJ419827], previously cloned from C. arabica [58], corresponded to the C. eugenioides (CaCe: RBCS1-Ce) allele, while the CcRBCS1 gene [GenBank:FR772689, this work] corresponded to the C. canephora (CaCc: RBCS1-Cc) allele. Horizontal arrows as well as nucleotides are in bold and italics and correspond to primer sequences. The 18244-F and -R primers were used to amplify the CcRBCS1 (Table 1). The RBCS-I1-F1 (RBCS_intron1_F1) and -R1 (RBCS_intron1_R1) primers were used for the mapping of the CcRBCS1 gene [64]. The stars below the alignments indicate identical bases, and the nucleotides are numbered for each lane. A schematic representation of the CaCe and CaCc genes is also given. Exons are boxed and numbers indicate fragment sizes in base pairs.

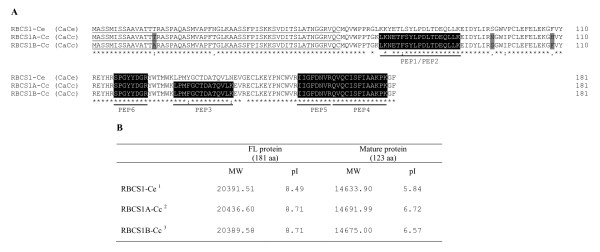

The characteristics of the RBCS1 proteins

An in silico analysis of these sequences was performed to define the characteristics of the corresponding RBCS1 proteins. All of them contained a 543-bp open reading frame coding for a protein of 181 amino acids (Figure 3A). The RBCS1-Ce (CaCe) protein was deduced from the unigene SGN-U607188 from C. arabica and was identical to that deduced from the CaRBCS1 cDNA and gene sequences. The protein has a theoretical molecular mass of 20391 Da and an estimated isoelectric point (pI) of 8.49 (Figure 3B). By homology with other chloroplastic proteins encoded in the nucleus [59], the first 58 amino acids corresponded to a putative chloroplast transit peptide. Consequently, the theoretical molecular mass of the mature RBCS1-Ce should be 14633 Da with a pI of 5.84. On the other hand, two isoforms of the RBCS1-Cc protein could be deduced from the nucleic sequences of C. canephora: RBCS1A-Cc coded by the RBCS1-Cc cDNA (this study) and RBCS1B-Cc deduced from the SGN-U607190 unigene. In their mature forms, the RBCS1A-Cc and RBCS1B-Cc proteins should have a molecular mass of 14691 and 14675 Da and estimated pIs of 6.72 and 6.57, respectively. This analysis suggests that different RBCS1 isoforms exist and are characterised by similar molecular weights but differing theoretical pIs.

Figure 3.

Sequence alignment and characteristics of the coffee RBCS1 proteins. (A): The amino acids corresponding to the chloroplastic transit peptide [1 to 58] are underlined. Identical amino acids are indicated by stars, conservative substitutions are indicated by two vertically stacked dots and semi-conservative substitutions are indicated by single dots. The RBCS1-Ce (CaCe) isoform from C. eugenioides corresponded to the proteins with the GenBank accession numbers CAD11990 and CAD11991 translated from the CaRBCS1 cDNA [GenBank:AJ419826] and gene [GenBank:AJ419827], respectively. The RBCS1A-Cc (CaCc) protein from the CcRBCS1 cDNA (FR728242) and gene (FR772689) sequences of C. canephora (this study) was strictly identical to the protein deduced from the SGN-U617577 unigene. The RBCS1B-Cc (CaCc) protein was deduced from the SGN-U607190 unigene. Divergent amino acids between RBCS1-Ce (CaCe) and RBCS1A-Cc (CaCc) proteins are boxed in grey, and those confirmed by mass spectrometry analysis (Table 6) are boxed in black. (B) The RBCS1-Ce (CaCe) protein deduced from the CaRBCS1 cDNA and gene sequences was identical to the protein deduced from the SGN-U607188 unigene (1). The RBCS1A-Cc protein was deduced from the RBCS1-Cc (identical to SGN-U6175772) cDNA and gene sequences from C. canephora (this study). The RBCS1B-Cc protein was deduced from the SGN-U607190 (3) nucleic acid sequence. Molecular weights (MW in Daltons), amino acids (aa) and isoelectric points (pI) are indicated for full-length (FL) and mature (without the chloroplast transit peptide) RBCS1 proteins. SGN sequences were obtained from the Sol Genomics Network http://solgenomics.net/content/coffee.pl.

RBCS1 gene expression in different genotypes and species of Coffea

According to the sequence alignments, primer pairs specific for each of the RBCS1 homeologous genes (CaCc = RBCS1-Cc and CaCe = RBCS1-Ce) were designed (Table 1) and quantitative PCR assays were performed to analyse RBCS1 expression in leaves of coffee plants from different species and genotypes by measuring the CaCc and CaCe expression levels (Table 2). From a technical point of view, cross-hybridisation of primers against the two different RBCS1 genes was excluded because the melting curves clearly separated the CaCc and CaCe amplicons produced using the C18244 and E18244 specific primer pairs, respectively (data not shown). Using the C18244 primer pair, high expression of the CaCc homeologous gene was observed in leaves of Conilon clones of C. canephora. On the other hand, CaCc was weakly expressed in leaves of C. arabica genotypes, particularly for those that did not undergo recent introgression with C. canephora genomic DNA, such as Typica, Bourbon, Caturra, Catuaí and Rubi, for example. The opposite situation was observed with the primer pair E18244, specific for the RBCS1-Ce (CaCe) haplotype from the C. eugenioides sub-genome of C. arabica. For C. eugenioides, the CaCc/CaCe expression was extremely low, which validates that there is almost an exclusive expression of the CaCe isoform in this species. Altogether, these results showed that CaCe and CaCc expression could be considered as negligible in C. canephora (high CaCc/CaCe ratio) and C. eugenioides (low CaCc/CaCe ratio), respectively. The results also demonstrated a large variability of CaCc expression in leaves of the two studied Timor hybrids. Both CaCc and CaCe homeologous genes were expressed to similar levels (CaCc/CaCe = 0.4) in the HT832/2 genotype, whereas CaCc expression was undetected (CaCc/CaCe = 4.10-5) in HT832/1 (Table 2). In introgressed C. arabica genotypes coming from breeding programs that used either HT832/2 or controlled crosses with C. canephora, a great variability in CaCc/CaCe ratios was also observed. For example, high CaCc expression was detected in leaves of the HT832/2-derived Obatã, Tupi, IAPAR59 (I59), IPR97 and IPR98 cultivars as well as in those of the interspecific controlled cross Icatú. However, CaCc gene expression was low in the HT832/2-derived IPR107 and Icatú-derived IPR102 and IPR106 genotypes. For all coffee genotypes analysed, levels of the total RBCS1 gene expression evaluated by the T18244 primer pair appeared quite similar (data not shown).

Table 1.

List of primers used for gene cloning and quantitative PCR experiments

| Gene name | Source gene | Primer name | Primer sequence | bp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBI * | SGN-U637098 |

BUBI-F BUBI-R |

5' AAGACAGCTTCAACAGAGTACAGCAT 3' 5' GGCAGGACCTTGGCTGACTATA 3' |

104 |

| GAPDH * | SGN-U637469 |

GAPDH-F GAPDH-R |

5' TTGAAGGGCGGTGCAAA 3' 5' AACATGGGTGCATCCTTGCT 3' |

59 |

| RBCS1-Cc (CaCc) |

SGN-U617577 FR728242 |

C18244-F C18244-R |

5' CCGTCCTCTTCCCCTCAAAT 3' 5' CCTGAAAGTACAGCCCCAGTTC 3' |

91 |

| RBCS1-Ce (CaCe) |

SGN-U607188 AJ419826 |

E18244-F E18244-R |

5' TTGGCCCCGGCCCCTCAAATT 3' 5' CAGCTAAAAGTACAGCCCCAGTTC 3' |

93 |

| RBCS1-T |

T18244-F T18244-R |

5' CTAGCATGGTTGCACCCTTCA 3' 5' AGTAATGTCGACGGACTTCTTGGA 3' |

77 | |

| RBCS1-DNA |

18244-F 18244-R |

5' GAGAATGGCATCCTCAATGATCTC 3' 5' CAGCCCCAGTTCTCAATTTTATTG 3' |

660(C) 648(E) |

Primers were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems). The source gene indicates the accession numbers of coffee cDNA and gene sequences found in the GenBank and SOL Genomics Network (SGN, http://solgenomics.net/content/coffee.pl[56]) libraries and used to design the primer pairs. The size of the amplicon is indicated in base pairs (bp). E: C. eugenioides corresponding to the CaCe (RBCS1-Ce isoform). C: C. canephora corresponding to the CaCc (RBCS1-Cc isoform). The RBCS1-T primer pair was used to amplify total-RBCS1 (CaCe+CaCc) transcripts. The RBCS1-DNA primer pair was used to amplify the CaCc cDNA and gene sequences. Primer sequences of reference genes previously reported by Barsalobres-Cavallari et al. [101] are also given (*).

Table 2.

The expression of RBCS1 isoforms in leaves of different coffee genotypes.

| Genotype | Cultivar | Origin | Trial | CaCc/CaCe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. canephora | ||||

| L21 | I | 65.93 | ||

| 14 T | Conilon | G | 1324.28 | |

| 22 S | Conilon | G | 247,10 | |

| 73 T | Conilon | G | 260.65 | |

| 120 T | Conilon | G | 236.71 | |

| C. arabica ("pure") | ||||

| Rubi S | Mundo Novo x Catuaí | E | 0.00013 | |

| Bourbon | I | 0.00014 | ||

| Typica | I | 0.00017 | ||

| Catuaí | Mundo Novo x Caturra | I | 0.00021 | |

| C. arabica ("introgressed") | ||||

| HT832/1 | Timor hybrid | E | 0.00004 | |

| HT832/2 | Timor hybrid | I | 0.40102 | |

| Icatú | C. canephora x Bourbon | I | 9.33 | |

| IAPAR59 T | Villa Sarchi x HT832/2 (Sarchimor) | I | 3.22 | |

| Tupi | Villa Sarchi x HT832/2 (Sarchimor) | I | 2.63 | |

| Obabã | [Villa Sarchi x HT832/2] x Catuaí | I | 1.26 | |

| IPR97 | Sarchimor | I | 4.98 | |

| IPR98 | Sarchimor | I | 21.65 | |

| IPR102 | Icatú x Catuaí | I | 0.00427 | |

| IPR106 | Icatú x Catuaí | E | 0.03212 | |

| IPR107 | Sarchimor x Mundo Novo | E | 0.12255 | |

| C. eugenioides | I | 0.00035 | ||

Expression was measured by the ratio CaCc/CaCe where CaCc (RBCS1-Cc) and CaCe (RBCS1-Ce) values were obtained using the C18244 and E18244 primer pairs (Table 1), respectively. Relative quantifications (RQ) were normalised using the expression of the CcUBQ10 (in the case of C. canephora) or GAPDH (for other species) reference genes. The CaCc/CaCe ratio corresponded to (1+E)-ΔCt, where ΔCt = CtmeanCaCc - CtmeanCaCe with E as the efficiency of the gene amplification. Leaves were collected from plants grown in the field at the Embrapa Cerrados (E), IAPAR station (I) and UFV greenhouse (G). When known, the reaction to drought is indicated (T = Tolerant and S = Susceptible). All Sarchimors are derived from HT832/2.

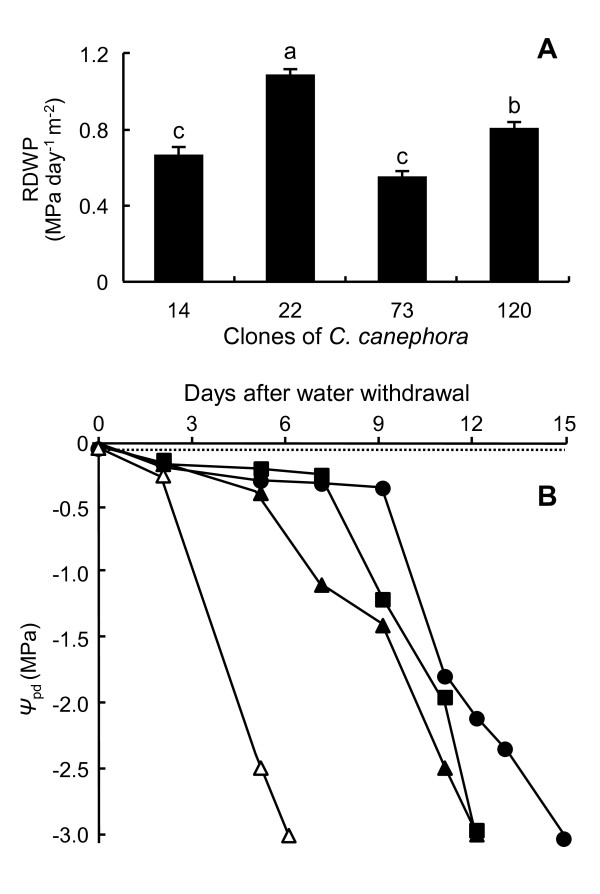

RBCS1 gene expression in leaves of C. canephora subjected to water stress

The rate of decrease in the predawn leaf water potential (Ψpd) (RDPWP) is one of the physiological parameters that distinguished the drought-susceptible clone 22 of C. canephora var. Conilon from the drought-tolerant clones 14, 73 and 120 [60,61]. To reach the imposed Ψpd of -3.0 MPa for the stressed (NI) condition in the greenhouse, the RDPWP decreased faster for the clone 22 than for drought-tolerant clones (Figure 4A). In this condition, the clones 22 reached the Ψpd of -3.0 MPa within six days, while clones 14, 73 and 120 reached the same within 12, 15 and 12 days, respectively (Figure 4B). As a control and for all the clones, the Ψpd values of plants under irrigation were close to zero, which confirms the unstressed condition.

Figure 4.

The evolution of predawn leaf water potentials (Ψpd) in the leaves of C. canephora. The clones 14, 22, 73 and 12 of C. canephora var. Conilon were grown in a greenhouse under water stress. The rate of decrease of Ψpd (RDPWP) is indicated for each clone without irrigation (NI) in MPa day-1 m-2 (A). Different small letters represent significant differences between means for drought-stressed clones by the Newman-Keuls test at P ≤ 0.05 (clone effect). Values are means ± SD of three replicates. (B) For each clone, Ψpd evolutions are presented relative to the days after water withdrawal (Δ, clone 22-NI; ▲, 14-NI; ■, 120-NI and ●, 73-NI).

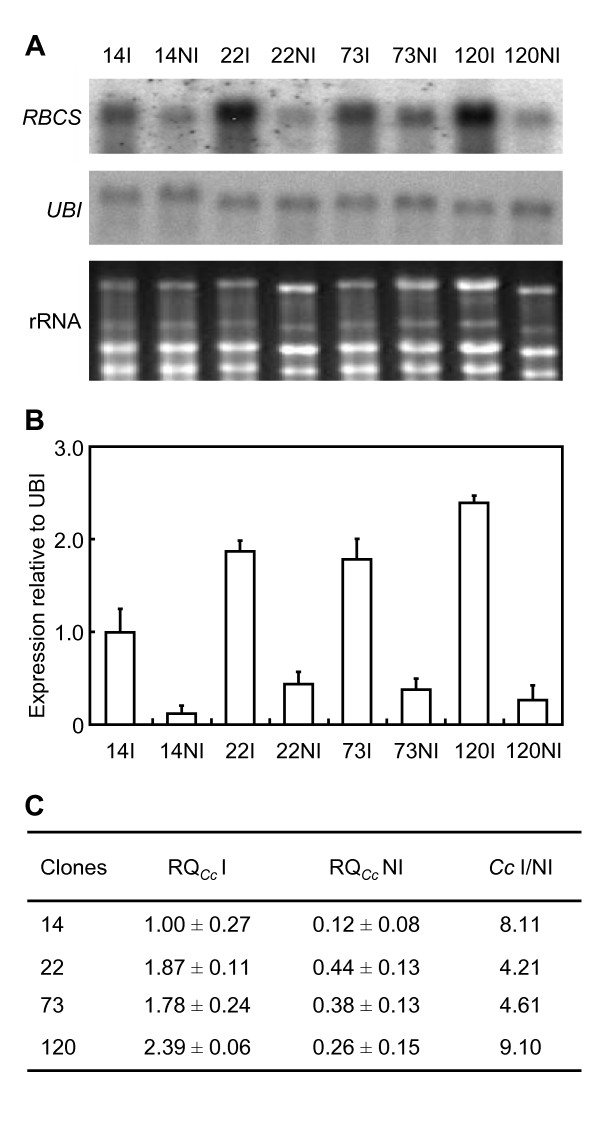

The effects of WS on RBCS1 gene expression were analysed in leaves of these clones grown under I and NI conditions by a northern blot experiment with an internal RBCS1 cDNA fragment as a probe (Figure 5A). For all the clones, RBCS transcripts of the expected size (approx. 0.9 kb) were highly detected under the irrigated condition and poorly accumulated under WS. As an internal control, the expression of the CcUBQ10 (ubiquitin) reference gene appeared equal for all samples. The expression of RBCS1 alleles was also studied by quantitative PCR (qPCR) for the same clones using the expression of the CcUBQ10 gene as an internal reference (Figure 5B). For all clones, the CaCe expression was negligible, and relative quantification of CaCc (RQCc) was chosen to reflect total RBCS1 expression (Figure 5C). This analysis also confirmed reduction of CaCc gene expression (CaCc I/NI ranging from 4- to 9-fold) with WS. In addition, some differences in RBCS1 expression were observed between the clones but they were not correlated with phenotypic sensitivity to drought. Identical qPCR results were also obtained using GAPDH as a reference gene (data not shown).

Figure 5.

The expression profiles of RBCS1 in C. canephora. For northern blot experiment (A), total RNAs (15 μg) were extracted from leaves of clones 14, 22, 73 and 120 of Conilon grown with (I) or without (NI) irrigation, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and hybridised independently with CcRBCS1 (RBCS) and CcUBQ10 (UBI) cDNA probes. Total RNA (rRNA) stained with ethidium bromide was used to monitor equal loading of the samples. (B) The qPCR analysis was performed using the C18244 primer pair specific for the CaCc isoform of the RBCS1 genes. Expression levels are indicated in relative quantification of RBCS1 transcripts using the expression of the CcUBQ10 gene as a reference. Results are expressed using 14I as an internal calibrator. In each case, values are the mean of three estimations ± SD. (C) Values of relative quantification (RQ) are given for clones 14, 22, 73 and 120 grown with (I, Ψpd ≈ -0.02 MPa) or without (NI, Ψpd ≈ -3.0 MPa) irrigation. RBCS1 targets correspond to the CaCc gene amplified with the C18244 primer pair. The I/NI ratio of RBCS1-Cc gene expression (Cc I/NI) is also indicated.

RBCS1 gene expression in leaves of young plants of C. arabica subjected to water stress

The effects of WS on RBCS1 gene expression were further analysed in leaves of young plants of Rubi and introgressed I59 cultivars grown in field conditions with (I) or without (NI) irrigation during two consecutive years (2008 and 2009). Two points of analysis were performed every year. The unstressed condition (U) corresponded to the rainy periods and the water stress (WS) condition to the dry season (Table 3). In this case, drought was not imposed but determined by the natural rainfall pattern during the dry-wet season cycle. For both cultivars, Ψpd values of irrigated plants, during the dry season, ranged from -0.11 to -0.38 MPa, demonstrating the absence of drought stress. For the NI treatment, lower (more negative) values of Ψpd were observed in 2008 than in 2009, demonstrating that the dry season was more severe during the former than in the latter. In addition, Ψpd values measured during the dry season of 2008 and 2009 were almost less negative for the cultivar I59 than for Rubi, indicating a better access to soil water for I59 than for the Rubi cultivar.

Table 3.

Predawn leaf water potentials (Ψpd) measured in field tests of C. arabica.

| Cultivar | Y | Irrigated (I) | Non-Irrigated (NI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U | WS | U | WS | ||||

| I59 | 2008 | -0.23 ± 0.09 | -0.38 ± 0.10 | -0.21 ± 0.05 | -0.80 ± 0.12 | ||

| Rubi | 2008 | -0.19 ± 0.02 | -0.22 ± 0.07 | -0.19 ± 0.06 | -1.88 ± 0.26 | ||

| I59 | 2009 | -0.06 ± 0.02 | -0.12 ± 0.00 | -0.07 ± 0.02 | -0.59 ± 0.03 | ||

| Rubi | 2009 | -0.06 ± 0.02 | -0.11 ± 0.00 | -0.13 ± 0.04 | -1.20 ± 0.16 | ||

| Icatú | 2010 | nd | <-4.0 | ||||

| Rubi | 2010 | nd | <-4.0 | ||||

| Obatã | 2010 | nd | <-4.0 | ||||

| I59 | 2010 | nd | <-4.0 | ||||

| Cultivar | Y | Irrigated (I) | Non-Irrigated (NI) | ||||

| U1 | WS | U2 | U1 | WS | U2 | ||

| I59 | 2008 | -0.41 ± 0.03 | -0.37 ± 0.05 | -0.14 ± 0.03 | -0.66 ± 0.03 | -1.35 ± 0.09 | -0.15 ± 0.03 |

| Rubi | 2008 | -0.28 ± 0.05 | -0.20 ± 0.04 | -0.17 ± 0.04 | -0.45 ± 0.04 | -1.96 ± 0.13 | -0.18 ± 0.03 |

Young (top) and adult (bottom) plants were grown under irrigated (I) or non-irrigated (NI) conditions. Ψpd values are expressed in mega-Pascal (MPa) and standard deviations (n = 9 leaves) are also indicated. For young plants, Ψpd was measured during the rainy season (U: unstressed) and the dry season (WS: water stress). For adult plants, Ψpd were measured only during the dry season (WS) under irrigated (I) or with the irrigation suspended for 90 days (NI) conditions. The points U1, WS and U2 corresponded to measurements before, during and after the return of irrigation, respectively. nd: Ψpd potentials were not determined but ranged from -0.1 to -0.2 MPa under irrigation. The year of analysis (Y) is also indicated.

Q-PCR reactions used the primer pairs E18244, C18244 and T18244 to detect CaCe (Ce), CaCc (Cc) and total-RBCS1 (RQRBCS1-T) expression, respectively (Table 4). Independent of water conditions, expression of both the CaCc and CaCe homeologs was always detected in the I59 cultivar, whereas CaCc expression was not detected in Rubi. It is also worth noting that total RBCS1 was mostly higher in I59 than in Rubi. For both cultivars, levels of RQRBCS1-Twere quite similar during the unstressed (rainy) condition of the year 2008. In comparison to the irrigated (I) condition, RQRBCS1-Twas reduced by 30% and 90% in NI plants of the I59 cultivar in 2008 and 2009, respectively. In both cases, this reduction affected mainly CaCc expression. For the Rubi cultivar, the absence of irrigation (NI) also reduced total RBCS1 expression by more than 80% in 2008 and 2009.

Table 4.

Daytime expression levels of RBCS1 genes in the leaves of young plants of C. arabica.

| Irrigated (I) | Non-Irrigated (NI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S - Y | RQCc | RQCe | RQRBCS1-T | Cc/Ce | RQCc | RQCe | RQRBCS1-T | Cc/Ce | |

| U-08 | 8.70 | 0.05 | 11.93 | 189.44 | (*) | (*) | (*) | (*) | |

| I59(1) | WS-08 | 32.80 | 0.09 | 32.66 | 253.33 | 21.83 | 0.13 | 22.49 | 167.92 |

| U-09 | 22.27 | 3.28 | 23.01 | 6.79 | 23.69 | 0.32 | 23.28 | 74.05 | |

| WS-09 | 10.80 | 0.66 | 12.33 | 16.36 | 3.06 | - | 3.61 | nd | |

| U-08 | - | 15.08 | 13.95 | - | (*) | (*) | (*) | (*) | |

| Rubi(1) | WS-08 | - | 14.39 | 12.15 | - | - | 1.97 | 2.25 | - |

| U-09 | - | 9.78 | 7.58 | - | - | 5.20 | 5.65 | - | |

| WS-09 | - | 13.40 | 13.27 | - | - | 2.37 | 2.64 | - | |

| Icatú(2) | WS-10 | 13.73 | 1.14 | 11.95 | 12.04 | 3.69 | 0.61 | 3.42 | 6.09 |

| Rubi(2) | WS-10 | - | 8.95 | 10.02 | - | - | 1.14 | 1.15 | - |

| Obatã(2) | WS-10 | nd | nd | 12.19 | - | nd | nd | 3.60 | - |

| I59(2) | WS-10 | nd | nd | 26.15 | - | nd | nd | 17.05 | - |

Nine-month-old plants (1: at the date of the U-08 point of analysis) grown in field conditions were studied during two consecutive years (2008 and 2009). Twenty-month-old plants (2: at the date of the WS-10 point of analysis) were analysed only during the dry season of 2010. For each cultivar, the season (S) and the year (Y) of analysis are indicated: U (unstressed condition) corresponding to the rainy season and WS (water stress) to the dry season. Corresponding predawn leaf water potentials (Ψpd) are given in Table 3. RBCS1 gene expression was expressed in relative quantification (RQ) for the I59 (IAPAR59), Rubi, Icatú and Obatã cultivars grown in the field with (I) or without (NI) irrigation. RBCS1 targets correspond to CaCe (Ce), CaCc (Cc) and total RBCS1 (RBCS1-T) transcripts amplified by the E18244, C18244 and T18244 primer pairs (Table 1), respectively. Cc/Ce values corresponded to RQCc/RQCeratios. For the U-08 point of harvest (*), qPCR analyses were not performed for non-irrigated (NI) plants that were considered identical to irrigated (I) ones. For the Rubi cultivar, CaCc gene expression was not detected (-). In that case, CaCe expression (RQCe) and total RBCS1 gene expression (RQRBCS1-T) was deduced from qPCR experiments that used the E18244 and T18244 primer pairs. For Obatã and I59 cultivars analysed in 2010, CaCe (Ce)- and CaCc (Cc)-specific expression was not determined (nd), and RQRBCS1-Twas deduced from qPCR experiments that used the T18244 primer pair. Results were normalised using the expression of the GAPDH reference gene.

RBCS1 expression was also studied in the young plants of the Icatú, Rubi, Obatã and I59 cultivars subjected (NI) or not subjected (I) to the severe WS that occurred during the dry season of 2010, as shown in the Table 3. In the irrigated condition, the I59 cultivar showed highest values of total RBCS1 expression, while RBCS1 expression in the Rubi, Icatú and Obatã cultivars was lower and more similar (Table 4). Under NI condition, RQRBCS1-Tdecreased for all cultivars, highly (-90%) for Rubi and to a lower extent (-70%) for Icatú and Obatã. Finally, the I59 cultivar was the genotype with the lowest decrease in RBCS1 gene expression; the value of RQRBCS1-T during the NI treatment was 65% of that observed under irrigation.

RBCS1 gene expression in leaves of adult C. arabica plants subjected to water stress: the effects of time of day

The effects of harvest hour on RBCS1 leaf expression were also studied using adult (eight-year old) plants of the Rubi and I59 cultivars grown in the field under continuous irrigation condition (I) or subjected to 90 days of WS during the dry season of 2008 (NI). The points of analysis were before (U1, unstressed), during (WS, water stress) and after (U2, unstressed) the dry season. As in young plants, the Ψpd values measured for the non-irrigated (NI) treatment during the WS period were less negative for I59 than for Rubi (Table 3). On the other hand, the Ψpd values ranged from -0.14 to -0.41 MPa for the irrigated (I) treatment, demonstrating the absence of WS.

CaCc expression (RQCc) decreased during the transition from U1 to WS under I and NI conditions in the I59 leaves harvested in the daytime (Table 5). However, CaCe gene expression was stable in plants irrigated continuously but decreased with WS in the NI condition. For the Rubi cultivar, CaCe expression (RQCe) was relatively stable under irrigated conditions for all points of the analysis. However, total RBCS1 expression (RQRBCS1-Tcorresponding to RQCe) decreased with WS under NI treatment. The comparison of total RBCS1 expression levels between the two cultivars revealed higher (from 2- to 5-fold) expression in I59 than in Rubi, with a predominant expression of the CaCc over the CaCe homeolog in the former. For both cultivars, total RBCS1 expression values were similar before (U1) and after (U2) the WS period, demonstrating gene expression recovery with the return of irrigation.

Table 5.

The expression levels of CaCc and CaCe isoforms in leaves of eight-year-old C. arabica.

| WT | Y | RQCc | RQCe | RQRBCS1-T | Cc/Ce | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U1-08 | 21.65 | 6.22 | 27.87 | 3.48 | ||

| I | WS-08 | 6.95 | 8.99 | 15.94 | 0.77 | |

| I59 | U2-08 | 35.17 | 6.21 | 41.38 | 5.66 | |

| U1-08 | 20.56 | 5.46 | 26.03 | 3.76 | ||

| NI | WS-08 | 11.74 | 1.60 | 13.34 | 7.33 | |

| U2-08 | 24.19 | 9.35 | 33.54 | 2.59 | ||

| U1-08 | - | 11.58 | 11.58 | - | ||

| I | WS-08 | - | 10.38 | 10.38 | - | |

| Rubi | U2-08 | - | 8.00 | 8.00 | - | |

| U1-08 | - | 15.99 | 15.99 | - | ||

| NI | WS-08 | - | 9.52 | 9.52 | - | |

| U2-08 | - | 12.46 | 12.46 | - | ||

| WT | Y | RQCc | RQCe | RQRBCS1-T | Cc/Ce | |

| U1-08 | 14.62 | 7.18 | 21.80 | 2.03 | ||

| I | WS-08 | 19.55 | 6.04 | 25.59 | 3.23 | |

| I59 | U2-08 | 25.90 | 11.81 | 37.72 | 2.19 | |

| NI | U1-08 | 35.32 | 8.16 | 43.48 | 4.33 | |

| WS-08 | 17.68 | 6.12 | 23.80 | 2.89 | ||

| U2-08 | 19.62 | 6.65 | 26.26 | 2.95 | ||

| U1-08 | - | 7.21 | 7.21 | - | ||

| I | WS-08 | - | 8.30 | 8.30 | - | |

| Rubi | U2-08 | - | 8.79 | 8.79 | - | |

| U1-08 | - | 14.05 | 14.05 | - | ||

| NI | WS-08 | - | 7.16 | 7.16 | - | |

| U2-08 | - | 8.12 | 8.12 | - | ||

Leaves of the cultivars I59 and Rubi were harvested in daytime (top: between 10:00 and noon) or night time (bottom: between 3:00 and 5:00 am). The points of analysis were before (U1, unstressed), during (WS, water stress) and after (U2, unstressed) the dry season of 2008. Corresponding predawn leaf water potentials (Ψpd) are given in the Table 3. The results of the relative quantification (RQ) are given for the cultivars IAPAR59 (I59) and Rubi grown in the field with (I) or without (NI) irrigation during the dry season (WT: water treatment). RBCS1 targets corresponded to CaCe (Ce) and CaCc (Cc) amplified by the E18244 and C18244 primer pairs (Table 1), respectively. Total RBCS1 expression (RQRBCS1-T) corresponded to RQCc+ RQCe, while Cc/Ce ratios corresponded to the RQCc /RQCeratios. For the Rubi cultivar, CaCc gene expression was not detected (-). Results were normalised using the expression of the GAPDH reference gene.

RBCS1 expression was also analysed when measuring Ψpd in leaves harvested at night (Table 5). As observed for daytime, total RBCS1 expression was higher in I59 than in Rubi. For the I59 cultivar, it is worth noting that total nocturnal RBCS1 expression during WS was higher than expression measured at daytime in the same plants. For Rubi, values of night-time RBCS1 expression were quite similar to those determined at daytime.

Accumulation of RBCS protein in leaves of C. canephora subjected to water stress

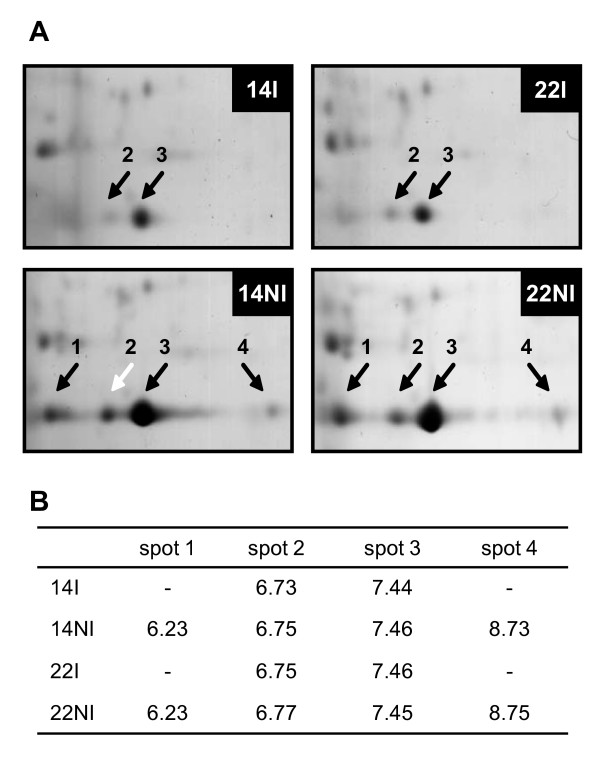

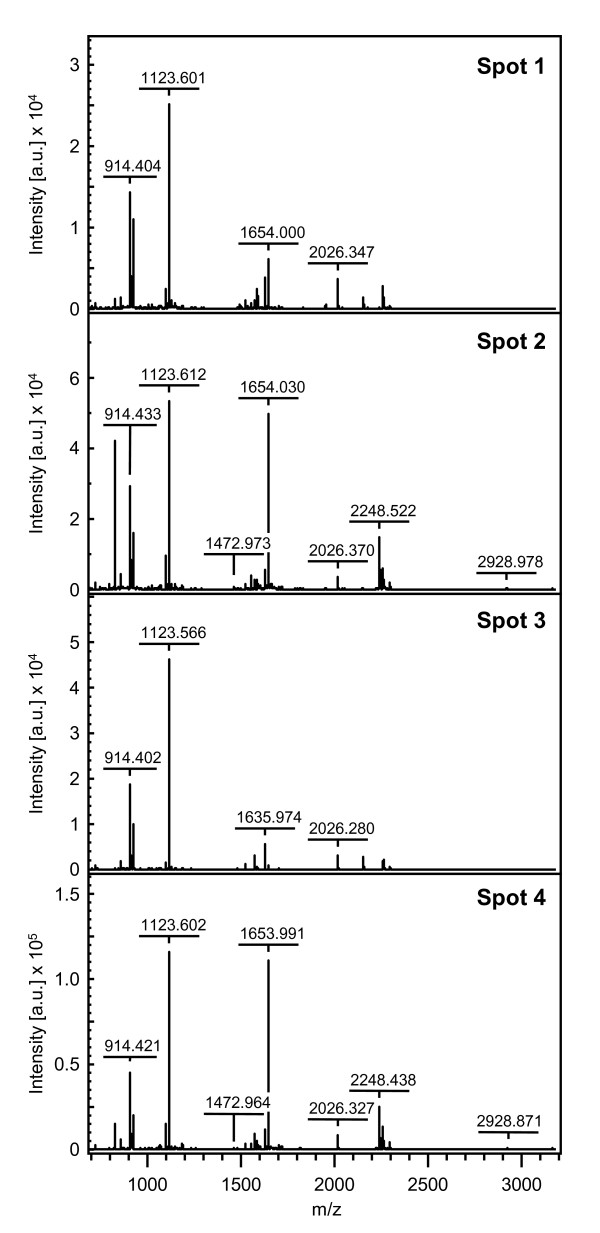

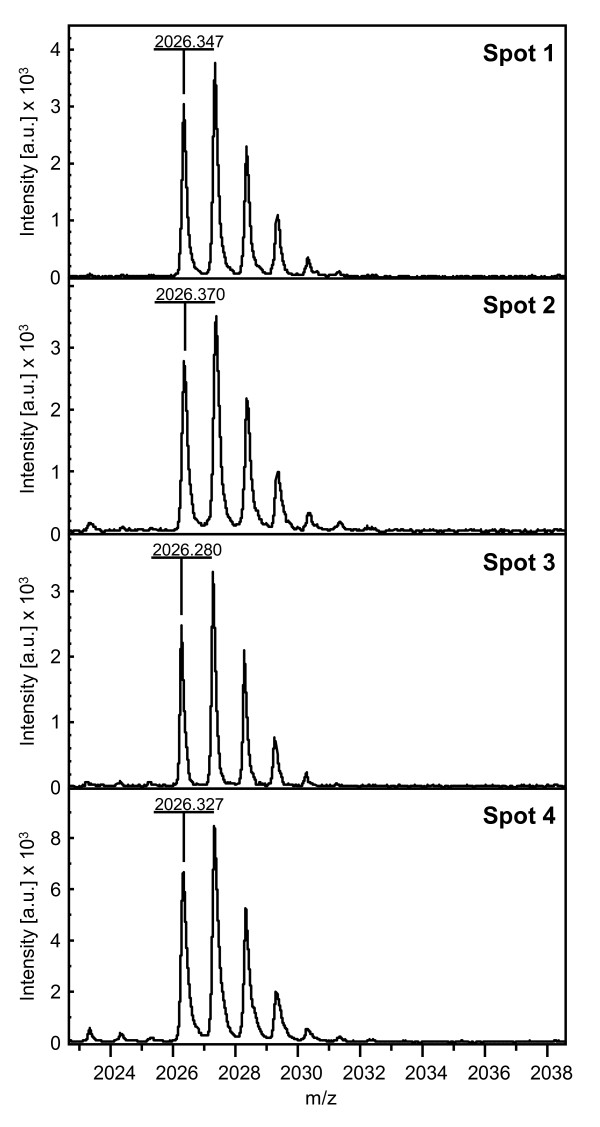

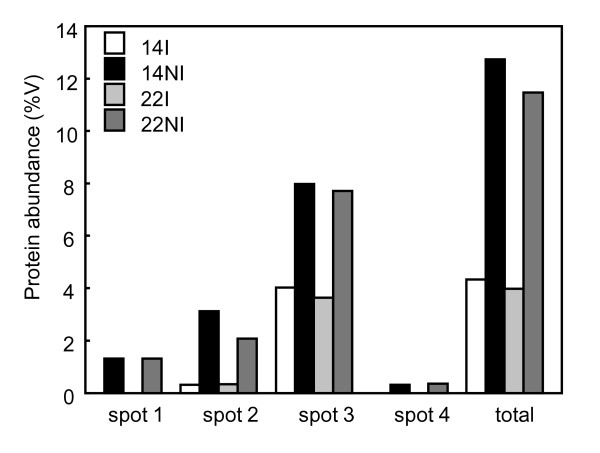

Soluble proteins were extracted from leaves harvested at night for clones 14 (drought tolerant) and 22 (drought susceptible) of C. canephora var. Conilon grown with (I) or without (NI) irrigation, and they were analysed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE). When looking at the gel portion containing the RBCS proteins, quantitative and qualitative changes of protein profiles were observed during WS (Figure 6A). For both cultivars, spots 2 and 3 were detected under the I and NI conditions. However, spots 1 and 4 were only detected under water stress. All were characterised by a similar molecular weight but differed in their pIs (Figure 6B). A detailed analysis of RBSC isoforms was performed for clone 14 under NI condition. Spot 2 (pI ≈ 6.7) was sequenced and resulted in six peptides (Table 6) that perfectly matched with the mature isoform of RBCS1 protein (Figure 3). Peptides 1 (M+H 2068.0) and 2 (M+H 2026.3) overlapped but differed in their N-terminal amino acid sequence by two residues. Peptides 4, 5 and 6 corresponded to the common regions of the CaCe and CaCc RBCS1 isoforms, while peptides 1, 2 and 3 matched only with the CaCc isoforms. For clone 14NI, the spectra of tryptic masses of spots 1 to 4 were very similar (Figure 7). Identical results were also obtained for spots 1 to 4 of clone 22NI (data not shown). In addition, peptide 2 corresponded to the ion M+H 2026.3 that was also observed in the spectra of all RBCS1 spots, which confirmed the similarity between these isoforms (Figure 8). For all of these isoforms, peptide mass fingerprinting of the tryptic digestion did not reveal post-translational modifications. This is justified by the fact that some tryptic peptides may not generally be represented in the mass spectrum, notably N-terminal peptides. Comparison of tryptic masses revealed that the ions with an m/z of 1472.9 and 1489.9, corresponding to peptide 4 (Figure 3A and Table 6), differed by 17 Da and characterised the loss of an ammonium group from the N-terminal sequence. They were present in RBCS1 spots 1 and 2 but absent in spots 3 and 4 (Figures 9 and 10). However, this peptide 4 was conserved in the CaCe and CaCc RBCS1 isoforms (Figure 3A). The normalised relative abundance, as evaluated by the percentage volume of the spots, clearly indicates an increase in all RBCS1 isoforms with drought stress (Figure 11). For example, the amount of RBCS spot 3 (pI ≈ 7.4) increased significantly under WS in the leaves of clones 14 and 22 (Figure 6A). However, quantitative differences between the two genotypes of C. canephora were not observed.

Figure 6.

Differential accumulation of RBCS subunits in leaves of C. canephora subjected to different water regimes. A: Proteins were extracted from clones 14 and 22 grown with (I) or without (NI) irrigation (14I, 14NI, 22I and 22NI) and analysed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE). Only parts of the 2-DE gels containing RBCS proteins are shown. Black arrows indicate RBCS spots. The RBCS1 protein analysed by MS/MS is shown by a white arrow. B: Isoelectric points (pI) of RBCS proteins identified by 2-DE gel electrophoresis. The pIs of were determined from calibrated 2-DE gels using ImageMaster Platinum 6.0 Software. The absence (-) of a pI value indicates that the isoform was not present in the gel.

Table 6.

Mass spectrometry analysis of the RBCS1 spot 2 isoform.

| Peptides | Mass (M+H) | position | peptide sequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2068.0015 | 68-86 | LKNETFSYLPDLTDEQLLK |

| 2 | 2026,3700 | 66-86 | NETFSYLPDLTDEQLLK |

| 3 | 1581.7596 | 130-143 | LPMFGCTDATQVLK |

| 4 | 1473.7050 | 167-179 | QVQCISFIAAKPK |

| 5 | 933.5152 | 159-166 | IIGFDNVR |

| 6 | 914.4002 | 116-123 | SPGYYDGR |

This spot was identified in the leaves of clone 14 of C. canephora under the WS condition. Six peptides from MALDI-TOF/TOF tryptic mass spectra (Figure 7) were sequenced by MS/MS ion search and de novo sequencing. They are also reported in Figure 3. The peptides position refers to the full-length RBCS1 protein. Peptide masses are shown as the monoisotopic mass (M+H).

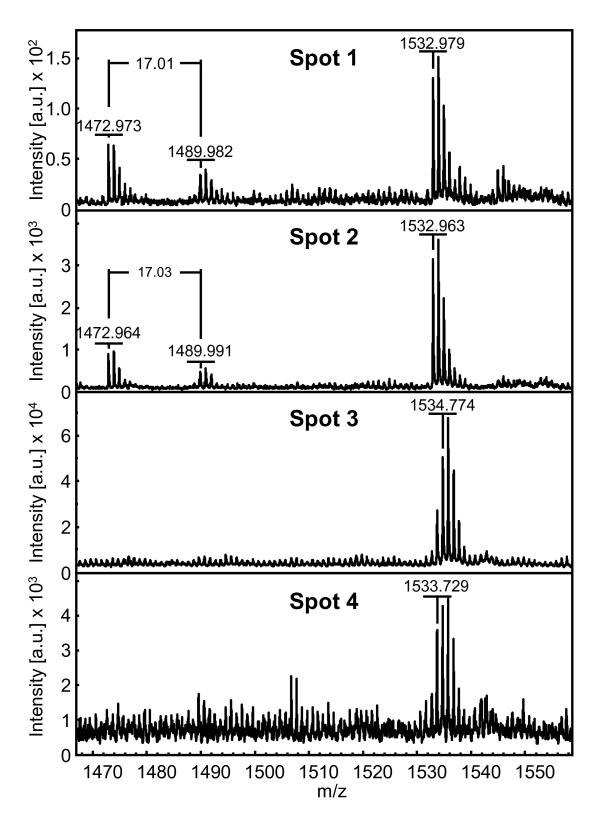

Figure 7.

Tryptic mass spectra of RBCS1 isoforms. The spot numbers correspond to the RBCS1 isoforms identified by 2-DE gel electrophoresis in the leaves of clone 14 of C. canephora under the NI condition (see Figure 6). The x-axis represents the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio and the y-axis represents the signal intensity of the ions expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.). For major peaks, corresponding monoisotopic m/z ratios are indicated.

Figure 8.

Magnification of the tryptic mass spectra of peptide 2. The spot numbers correspond to the RBCS1 isoforms identified by 2-DE in the leaves of clone 14 of C. canephora under the NI condition. The x-axis represents the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio, and the y-axis represents the signal intensity of the ions expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.). The mass differences of the peaks correspond to the mass accuracy of MALDI-TOF/TOF.

Figure 9.

Magnification of the tryptic mass spectra of the ions M+H 1472.9 and M+H 1489.9. The spot numbers correspond to RBCS1 isoforms identified by 2-DE gel electrophoresis in the leaves of clone 14 of C. canephora under NI conditions. The x-axis represents the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio and the y-axis represents the intensity of peaks expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.). The mass difference between ions of 17 Da corresponds to the loss of ammonia.

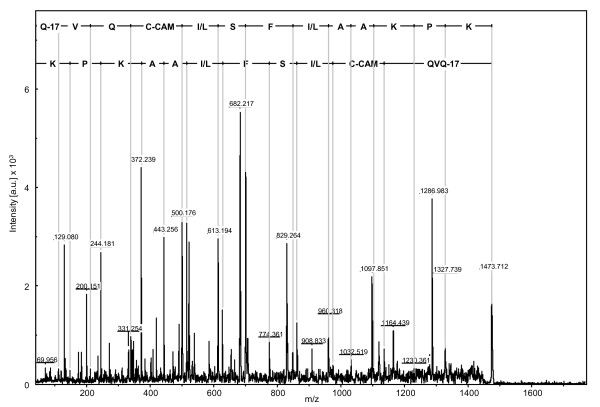

Figure 10.

MS/MS mass spectra of the ion M+H 1472.973 (peptide 4). This ion was isolated from RBCS1 spot 1 of clone 14 of C. canephora under NI conditions. The amino acid sequence of peptide 4 is indicated in the upper part of the graph. The x-axis represents the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio, and the y-axis represents the intensity of peaks expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.).

Figure 11.

Normalised protein abundance of RBCS1 isoforms. Protein abundance was measured in clones 14 and 22 of C. canephora subjected (NI) or not subjected (I) to WS from the 2-DE and expressed in percentage volume (%V) of spots analysed by ImageMaster Platinum 6.0 software.

Discussion and conclusions

The mechanisms regulating Rubisco activity and its abundance during water stress (WS) are not well characterised. Some works have reported that the loss of Rubisco activity constitutes an early response to WS [37]. In contrast, there is also evidence that more severe stress or stress applied for a longer period also decreases the amount of Rubisco [62]. Numerous studies have investigated the expression of the RBCS genes in response to light or in different tissue types and have shown that transcripts from individual genes accumulate differently [for a review, see [63]]. In higher plants, the RBCS genes are very similar to each other, which results in only a few amino acid differences in the RBCS proteins. Considering that RBCS complements the structure of RBCL and that evolution is likely to have resulted in specialisation of the different RBCS proteins, it is possible that different RBCS genes may have different impacts on Rubisco activity and regulation [34]. In this context, the main aims of this work were to identify the alleles of coffee RBCS1 gene, to determine the expression of these genes in different species with an emphasis on the polyploid species C. arabica and to study the effects of WS on RBCS1 expression in different genotypes and environmental conditions.

The existence of homeologous coffee RBCS1 genes was revealed through a search of public databases of coffee ESTs homologous to the CaRBCS1 cDNA sequence previously cloned from C. arabica [53]. Here, we report the cloning and sequencing of the RBCS1 cDNA and its corresponding gene from C. canephora (RBCS1-Cc). Nucleic acid alignments demonstrated that the RBCS1-Cc cDNA matched with RBCS1 ESTs expressed in both the C. canephora and C. arabica cDNA libraries [55,56]. In the latter species, RBCS1 ESTs identical to the previously-cloned CaRBCS1 cDNA and gene sequences also corresponded to a RBCS1 read in C. eugenioides. RBCS1 sequence alignments also revealed the existence of some nucleic differences that could correspond to sequencing errors or real SNPs that characterise the different alleles of RBCS1. Access to coffee whole genome sequences could help to resolve these points [52]. It is also worth noting that all the RBCS genomic sequences amplified from the 12 different genotypes of C. arabica (L.S. Ramirez, unpublished results) were identical to CaRBCS1 rather than RBCS1-Cc. This should be explained by the fact that these genes were probably amplified by specific primers that recognise the CaRBCS1 allele carried by the C. eugenioides sub-genome. Altogether, these results clearly showed that two homeologous RBCS1 genes were expressed in C. arabica, one from the CcRBCS1 gene (also called CaCc), which was carried by the C. canephora sub-genome of C. arabica, and the other from the CaRBCS1 gene (also called CaCe), which was carried by the C. eugenioides sub-genome of C. arabica. Thus, our results once again confirmed that the ancient C. canephora and C. eugenioides genomes constitute the two different sub-genomes of C. arabica [3,4]. Comparison of the RBCS1-Cc and RBCS1-Ce (corresponding to CaRBCS1) gene sequences also revealed interspecific sequence polymorphisms characterised by several indels mainly in the introns and in the 3' UTR region. Intraspecific sequence polymorphisms were also observed in C. canephora, and they permitted the recent mapping of the CcRBCS1 gene to the G linkage group of the C. canephora genetic map [64].

The expression variability of RBCS1 alleles was further tested in different coffee species and genotypes of C. arabica using specific primer pairs designed to the 3' UTR region of the RBCS1 cDNAs. Our results clearly demonstrated high CaCc (with negligible expression of CaCe) expression in C. canephora and high CaCe (with negligible expression of CaCc) expression in C. eugenioides. After this validation, expression of the homeologous RBCS1 genes was analysed in the different genotypes of C. arabica. These highlighted the predominant expression of the homeologous CaCe over the CaCc genes in the leaves of non-introgressed ("pure") C. arabica cultivars such as Typica, Bourbon and Catuaí; the former two cultivars correspond to the base populations that generated the latter cultivar [65,66]. In a previous study, Petitot et al. [67] also reported that the CaWRKY1a and CaWRKY1b genes of C. arabica, which encode for transcription factors of the WRKY family, originated from the two parental sub-genomes of this coffee species. In that case, CaWRKY1a and CaWRKY1b were concomitantly expressed, and both homeologous genes contributed to the transcriptional expression of coffee defence responses to pathogens. The result presented here are quite different, because they clearly highlighted the predominant expression of the CaCe over the CaCc homeologous gene for the non-introgressed genotypes of C. arabica and suggested that specific suppression of CaCc expression occurred during the evolutionary processes that led to the creation of the C. arabica species. This observation is in agreement with the recent results of Vidal et al. [4], who reported that within C. arabica, the C. eugenioides sub-genome may express genes coding for proteins that assume basal biological processes (as is the case for photosynthesis), while the C. canephora sub-genome contributes to adjust Arabica gene expression by expressing genes coding for regulatory proteins.

Another noteworthy result concerned the differential expression of the RBCS1 homeolog genes in Timor hybrids HT832/1 and HT832/2 as well as in the Icatú- or HT832/2-derived (introgressed) varieties. The qPCR experiments presented here clearly showed that the CaCe and CaCc homeologs were co-expressed with the same order of magnitude in HT832/2, while CaCc expression was undetectable in HT832/1. Most of the HT832/2-derived cultivars showed preferential expression of CaCc over the CaCe homeolog. However, Icatú-derived IPR102 and IPR106, as well as HT832/2-derived IPR107, presented the inverse situation of low expression of CaCc. The simplest hypothesis would be the existence of one or several genetic factors activating the expression of sub-genome CaCc genes in the C. canephora (Cc) species when introgressed with C. arabica. The RBCS1-Cc gene itself might be this genetic factor, but it might also be one or several other introgressed genes involving epistatic regulation. Epistasis is now proven to have a crucial role in gene regulation [68] and even in the heterosis phenomena [69]. Under this hypothesis, pure C. arabica does not express RBCS1-Cc in the absence of the Cc genetic factor. Introgressed C. arabica does or does not include the Cc genetic factor depending on the actual Cc genome introgressed. During selection from introgressed material, the percentage of the Cc genome tends to decrease because i) backcrosses are often directed toward a pure C. arabica parent and ii) phenotypic selection is directed towards C. arabica characteristics. Indeed, only disease-resistant genes from C. canephora are desired, while other genes that are part of the genetic drag lead to a decrease in cup quality [70,71]. The recently introgressed C. canephora genome has been estimated to represent 8 to 27 percent of the whole genome of introgressed varieties of C. arabica [5]. However, Bertrand et al [71] showed that differences in the cup quality of various introgressed varieties was not explained by the quantity of the introgressed C. canephora genome, thus suggesting that the types of introgressed genes are more important than the quantity of introgressed genome. In our study, it could be hypothesised that the Cc genetic factor is absent in HT832/1 and present in HT832/2 accessions of Timor hybrids. HT832/2-derived introgressed lines express RBCS1-Cc if the Cc factor has been maintained in the selection process. This would be the case for all HT832/2-derived varieties except in IPR107, which might have lost the Cc genetic factor during selection. Under this hypothesis, both Icatú-derived genotypes IPR102 and IPR106 would have lost the Cc genetic factor. No HT832/1-derived varieties were part of our study. However, such varieties should not express RBCS1-Cc, as the Cc factor would be absent in HT832/1. Checking the expression of RBCS1-Cc in HT832/1-derived varieties would thus reinforce or discard the hypothesis of a Cc genetic factor that epistatically regulates the expression of this gene. However, RBCS1 represents a potentially useful model to explore the differential expression of both the CaCc and CaCe sub-genome of C. arabica. Such experiments would advance our understanding of how epistasis regulates the gene expression of different sub-genomes in an amphidiploid species. Differential gene expression from both whole sub-genomes of C. arabica has been recently studied through a coffee-specific microarray [72]. This work allowed a more specific study that showed a preferential general expression of CaCc and CaCe genes at higher and lower temperatures, respectively [73]. Well-designed RBCS1 expression studies might provide a powerful single gene model for drought resistance and epistatic regulation in an amphidiploid and may contribute to a better understanding of epigenetic regulation in plant polyploids and its relationship to polyploidy advantages [74]. Recent genomic resources from C. canephora, including a dense genetic map [64], will help precise tracking of the introgressed C. canephora genome and possibly aid in understanding the functioning of the Cc genetic factor responsible for CaCc expression in introgressed varieties.

Another aim of this work was to study the effects of WS on RBCS expression in different coffee species. In higher plants, several works reported the rapid decrease in abundance of RBCS transcripts with WS and, consequentially, a reduction in RBCS protein accumulation in leaves [30-34,75]. In our conditions, it is worth noting that the decreases of Ψpd were much slower for field-grown plants of C. arabica than those for C. canephora grown in a greenhouse. In addition, and except in 2010, the Ψpd values observed for C. arabica during the period of maximum WS, were much less negative than those of C. canephora. This clearly demonstrated that the WS conditions were not equivalent between the two studies and that the stress suffered by the clones of C. canephora was more severe than the stress applied to the Rubi and I59 cultivars of C. arabica. For the latter and in young and adult plants, Ψpd values under WS always appeared less negative for I59 than Rubi indicating better access to soil water for the former than the latter [76]. Regarding RBCS1 gene expression, the results presented here clearly showed a drastic decrease in total RBCS1 transcripts with severe WS for C. canephora. Irrespective of the clone analysed, total RBCS1 (CaCc) gene expression was reduced by 75% in WS-plants with a leaf predawn water potential (Ψpd) of -3.0 MPa. Independently of plant age, a drought-induced decrease of total (daytime) RBCS1 transcripts was also observed for the two field-grown cultivars (Rubi and I59) of C. arabica subjected to WS. For I59, WS reduced the daytime expression of both the CaCc and CaCe homeologous genes, whereas only CaCc expression declined at night. Q-PCR experiments showed higher RBCS1 gene expression in I59 but also showed a lower extent of gene expression for the Icatú and Obatã cultivars than for the Rubi cultivar. For the latter, total RBCS1 gene expression was lower at night time than at daytime suggesting reduced transcription or an increase in transcript turnover under nocturnal conditions. However, the opposite seems to occur for the I59 cultivar, which shows a nocturnal increase in total RBCS1 gene expression, mainly mediated by enhanced CaCc expression. Together with the Ψpd measurements, these results demonstrate the different behaviours of C. arabica cultivars during drought stress and suggest that those introgressed with a C. canephora genome could better tolerate WS conditions than cultivars of "pure" C. arabica.

It is well known that expression of the RBCS genes is positively regulated by light [for a review, see [77]]. In addition, several works also reported that increased sugar (e.g., glucose and fructose) levels can trigger repression of photosynthetic gene transcription including RBCS [24]. However, diurnal RBCS expression and light/dark oscillation of RBCS mRNA in an inverse timeframe to the normal daytime accumulation and night mobilisation of leaf carbohydrates previously reported [78-81]. Praxedes et al. [82] showed increased concentration of sucrose and hexoses, probably coming from enhanced starch degradation, in WS leaves of clone 120 of C. canephora that could also be explained by the daytime decrease of RBCS1 transcripts reported here.

In order to see if this reduction in RBCS1 gene expression also affected the amount of the corresponding protein, 2-DE experiments were performed to study RBCS1 proteins in the leaves of clones 14 (drought-tolerant) and 22 (drought-susceptible) of C. canephora var. Conilon grown with (I) or without (NI) WS. For both clones, drought stress increased the amount of the main RBCS1 isoform corresponding to spot 3 and also led to the accumulation of at least three other RBCS isoforms of identical molecular weight but different pIs. Comparison of the tryptic mass profile by peptide mass fingerprinting revealed the absence of some peptides in the different RBSC1 isoforms, such as for spots 3 and 4, that did not contain peptide 4. In addition, other ions that could correspond to this peptide were not found. It is possible that peptide 4 was not detected due to posttranslational modifications that modify its mass. Another possibility is that spots 3 and 4 really corresponded to RBCS alleles that differed from RBCS1 proteins as in C. arabica, where differential expression of RBSC alleles under drought stress was observed (Ramos, personal communication). In the literature, few examples showed up-regulation of RBCS gene expression with drought stress accompanied by the Rubisco increase [83-85]. Altogether, the results presented here suggest a decoupling between RBCS1 gene expression and the accumulation of RBCS1 protein during WS.

Several hypotheses could be proposed to explain why the decline of photosynthetic CO2 fixation (A) with drought stress previously reported for clones 14 and 120 of C. canephora var. Conilon [60] is not accompanied by a decrease in amount of RBCS1 protein. The first hypothesis could involve the participation of Rubisco binding proteins (RBP) that stabilise, protect and activate the Rubisco holoenzyme under adverse environmental conditions [86]. Proteins such as chaperones, Rubisco activase, Clp ATP-dependent calpain protease and detoxifying enzymes have been shown to play such roles that favour Rubisco accumulation and stabilisation by preventing its damage under drought stress [26,41]. It is worth noting that WS increased expression of genes coding for small HSP proteins, as observed in the leaves of clones 14 and 22 of C. canephora [87]. In addition, high activities of detoxifying enzymes (e.g., ascorbate peroxidase and superoxide dismutase) were also reported in the leaves of water-stressed clones 14 and 120 of C. canephora [47]. The second possibility is that accumulation of RBCS1 protein could come from the expression of other RBCS alleles up-regulated during WS to compensate for the down-regulation of RBCS1. However, because the decrease of RBCS1 gene expression was confirmed by qPCR experiments using different primer sets, including one pair designed to the RBCS-coding sequence that should be extremely conserved within the coffee RBCS gene family, this hypothesis seems unlikely. A third possibility is that RBCS1 protein accumulated under WS came from the translation of RBCS1 mRNA transcribed overnight. This hypothesis cannot be completely ruled out because nocturnal RBCS1 expression was effectively observed in leaves of the I59 and Rubi cultivars of C. arabica. In that case, nocturnal accumulation of RBCS1 mRNAs could participate in maintaining the high daytime amount of RBCS1 protein even under a sharp reduction in RBCS1 gene expression. This should also favour a quick recovery of photosynthetic capacity under favourable environmental conditions and help coffee plants to cope with WS [38].

Water stress can directly affect photosynthesis by causing changes in plant metabolism or by limiting the amount of CO2 available for fixation [35]. Although stomatal closure generally occurs when plants are exposed to drought, in some cases photosynthesis may be more controlled by the capacity to fix CO2 than by increased diffusive resistance [88]. If Rubisco is not a limiting enzyme for carbon fixation under drought, the impaired activity of enzymes involved in the regeneration of Rubisco or in the Calvin cycle (e.g., sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase and transketolase) could be responsible for the drought-induced decrease in photosynthetic capacity [89]. In addition to the carboxylase activity, Rubisco has also oxygenase activity. This process, called photorespiration, can protect the photosynthetic apparatus against photoinhibition by keeping the electron transport chain active, thus limiting electron accumulation and ROS formation. This could explain why photoinhibitory damages were not observed in water-stressed coffee plants [47,60,90]. In that case, Rubisco could confer acclimatisation to oxidative stress under water deficit. The true mechanism of Rubisco contribution to water and oxidative stress responses in coffee plants still remains obscure and highlights the necessity for additional detailed studies to precisely determine its contribution.

The work presented here is the first to (a) investigate the effects of drought stress on gene expression with coffee plants grown in the field, (b) compare these results with those obtained for coffee plants grown under WS intensities and (c) analyse the transcriptome response of the two main coffee species, while taking into account the complex regulation of homeolog genes in C. arabica and opening the way to further sharpen understanding of epistatic regulation of sub-genome expression in an amphidiploid species. These results constitute only one part of a broader project that aims to study the effects of drought stress on biomass, architecture, anatomy and eco-physiological parameters of Rubi and I59 cultivars [61,91]. The integration of these data with ongoing studies of candidate genes should help us to understand the genetic determinants of drought tolerance in coffee, which constitutes an essential step in the improvement of coffee-breeding programs.

Methods

Plant material

Different plant material was used in this study depending on the specific experiments. So-called Timor Hybrids were not first-generation crosses but rather originated from various backcrosses with C. arabica after an initial cross [92]. The main three Timor Hybrids (HT832/1, HT832/2 and HT1343) were used in C. arabica breeding programs [5,93]. In our study, all Timor Hybrid introgressed varieties were derived from HT832/2. Controlled crosses also led to the Icatú F1 cross between C. canephora and C. arabica [94]. After backcrosses with C. arabica, Icatú-derived varieties were selected. In summary, we used the following material (Table 2):

• two diploid species: C. canephora (Cc) and C. eugenioides (Ce)

• four varieties of C. arabica amphidiploid species whose sub-genomes are related to present C. canephora (CaCc) and C. eugenioides (CaCe)

• one controlled F1 cross between C. canephora and C. arabica: Icatú

• two natural C. arabica introgressed hybrids: HT832/1 and HT832/2

• various introgressed HT832/2- or Icatú-derived varieties

Evaluation of RBCS1 gene expression in different genotypes of C. arabica

The plants of the genotypes Tupi, Bourbon, Typica, Catuaí, HT832/1, HT832/2 and IPR (97 to 107 [93]) from C. arabica as well as plants of C. eugenioides and C. canephora (clone L21) were cultivated on the coffee collection of the IAPAR (Instituto Agronômico do Paraná, Londrina, Brazil 23°21'17"S - 51°10'00"W) experimental station without WS (Table 2).

The effects of water stress on RBCS1 gene expression in C. canephora

Drought stress experiments used C. canephora clones (drought-tolerant: 14, 74 and 120; drought-susceptible 22) of the Conilon variety previously identified by the Incaper (Instituto Capixaba de Pesquisa, Assistência Técnica e Extensão Rural, Espírito Santo, Brazil). Rooted stem cuttings were grown in greenhouse conditions (UFV- Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil) in small (12 l) containers [95]. When the plants were 6 months old, water deficit was imposed by withholding watering to reach a predawn leaf water potential (Ψpd) of around -3.0 MPa for WS condition (Figure 4).

The effects of water stress on RBCS1 gene expression in young C. arabica plants

Young (4-month-old) seedlings of the cultivars Rubi MG1192, Icatú, Obatã and IAPAR59 (I59) of C. arabica [96] were planted (0.7 m within plants and 3 m between rows) at the Cerrados Agricultural Research Center (Planaltina-Distrito Federal, Brazil 15°35'44"S - 47°43'52"W) of the Embrapa, in full sun conditions in December 2007 and cultivated with (I) or without (NI) irrigation [76]. For the irrigated (I) condition, water was supplied by sprinklers (1.5 m height) organised in the field to perform uniform irrigation. Soil water content was controlled using PR2 profile probes (Delta-T Devices Ltd), and regular irrigations were performed to always maintain the water content above 0.27 cm3 H2O cm-1. The points of analysis corresponded to the rainy (U, unstressed) and dry (WS, water-stress) seasons (Table 3).

The effects of water stress on RBCS1 gene expression in adult C. arabica plants

Adult (8 year old) C. arabica cv. Rubi and I59 plants were grown at the Cerrados Center in full sun conditions under continuous irrigation (I) or irrigation suspension (NI) during the dry season in 2008. The points of analysis were before (U1, unstressed), during (WS, water-stress) and after (U2, unstressed) the irrigation suspension period (Table 3). Irrigation conditions were identical to those described for young plants.

Sample analysis and preparation

For both C. arabica and C. canephora, water stress levels were evaluated by measuring predawn leaf water potentials (Ψpd) with a Scholander-type pressure chamber (Table 5) using fully expanded leaves (8-15 cm long) from the third or fourth pair from the apex of plagiotropic branches localised in the third upper part of the plant canopy. Leaves were collected between 3:00 and 5:00 am (night-time). For C. arabica, quantitative PCR (qPCR) experiments used leaves harvested at night (at the time of Ψpd measurements) or between 10:00 and noon (daytime). For C. canephora, leaves were collected between 10:00 and noon for qPCR, Northern blot and 2-DE experiments. In that case, they were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and further conserved at -80°C before extraction.

RNA isolation

Samples stored at -80°C were ground into a powder in liquid nitrogen, and total RNAs were extracted using the "Plant RNA Purification Reagent" (PRPR) method (Invitrogen). Around 50 mg of powder was added to 500 μl of PRPR buffer, mixed vigorously for 2 min at 25°C and then centrifuged (16000 × g, 2 min, 4°C). After the addition of 5 M NaCl (100 μl) and chloroform (300 μl) to the supernatant, the sample was centrifuge as previously described. One volume of isopropanol was further added to the supernatant. After incubation at 25°C for 30 min, nucleic acids were precipitated by centrifugation (16000 × g, 30 min, 4°C), and the pellet was dried and dissolved in 40 μl of RNAse-free water and stored at -20°C. RNA quantification was performed using a NanoDrop™ 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Northern blot experiments

Fifteen micrograms of total RNA were fractionated on a 1.2% (w/v) agarose gel containing 2.2 M formaldehyde in MOPS buffer. Equal amounts of RNA samples were loaded and controlled by the abundance of the 26S and 18S rRNA on gels stained with ethidium bromide. The CcRBCS1 [GenBank:GT649534] and CcUBQ10 [GenBank:GT650583] probes were amplified by conventional PCR using universal primers from the plasmid harboring the corresponding EST sequences, and labelled by random priming with α-32P-dCTP (GE Healthcare) as previously described [97]. RNAs were transferred to Hybond N+ membranes followed by hybridisation at 65°C in modified Church and Gilbert buffer (7% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5 M sodium phosphate pH 7.2) and washed at 65°C in 2 × standard saline citrate (SSC; 1 × = 150 mM sodium chloride and 15 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0), 0.1% SDS (2 × 15 min), with a final stringent wash in 0.1 × SSC, 0.1% SDS (2 × 15 min). Membranes were exposed with BAS-MS 2340 IP support, and the data was acquired using a Fluorescent Image Analyzer FLA-3000 (Fujifilm Life Science). When necessary, membranes were stripped and tested with a new probe.

Cloning of the CcRBCS1 cDNA and gene sequences

The primer pair 18244 (RBCS1-DNA, Table 1), common to all cDNA of RBCS1 isoforms, was used to amplify RBCS1 cDNA sequences from the Rubi cultivar of C. arabica (pure C. arabica without introgression of C. canephora) and clone 14 of C. canephora var. Conilon, respectively. PCR was performed using a PTC-100 Thermocycler (MJ Research) with Taq Platinum DNA polymerase according to the supplier (Invitrogen) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, Ta = 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 3 min, and a final extension step of 72°C for 7 min. The quality of the amplicons was verified by electrophoresis. PCR fragments were cleaned using the Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega) and double-strand sequenced without cloning using the primers used for the PCR and the BigDye Terminator Sequencing Kit v3.1 chemistry on an ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). For the cloning of the CcRBCS1 gene, fresh leaves from clone 14 of C. canephora were collected in the greenhouse, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and used to extract genomic DNA as described previously [97]. The CcRBCS1 gene was amplified from genomic DNA (10 ng) using the primer pair 18244 (Table 1) and PCR conditions identical to those described before for the isolation of CcRBCS1 cDNA. The fragment obtained was cloned in pTOPO2.1 (Invitrogen) and double-strand sequenced.

Multiple alignments

Multiple alignments of nucleic and protein sequences using sequences available from the online Sol Genomics Network (SGN, http://solgenomics.net/content/coffee.pl[56]) were obtained by the CLUSTALW program [98] followed by manual adjustment.

Real time RT-PCR assays

To eliminate contaminant genomic DNA, samples were treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and RNA quality was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and visual inspection of the ribosomal RNA bands upon ethidium bromide staining. Synthesis of first strand cDNA was accomplished by treating 1 μg of total RNA with the ImProm-II™ Reverse Transcription System and oligo (dT15) according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Promega). The absence of contaminating genomic DNA in the cDNA preparations was checked by common PCR reaction using SUS10/SUS11 primer pair that spans introns 5 to 9 of the CcSUS1 gene (AJ880768), which encodes isoform 1 of the sucrose synthase from C. canephora [99]. RT-PCR was carried out using 1 μl of synthesised cDNA under conventional PCR conditions using a PTC-100 Thermocycler (MJ Research) with GoTaq DNA polymerase according to the supplier (Promega) with the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 94°C, Ta = 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 3 min and a final extension step of 72°C for 6 min. In such conditions, the amplification of a 667-bp fragment characterised the CcSUS1 cDNA, and the absence of corresponding genomic sequence is indicated by the lack of an amplicon at 1130-bp (data not shown).