Abstract

Background: The incidence and risk factors of central nervous system (CNS) involvement in peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) are still unclear.

Patients and methods: We analyzed 228 patients with PTCLs, excluding cases of extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma and primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, by retrospectively collecting the clinical features and outcomes of the patients.

Results: Twenty events (8.77%, 20/228) of CNS involvement were observed during a median follow-up period of 13.9 months (range 0.03–159.43). Based on univariate analysis, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level [P = 0.019, relative risk (RR) 5.904, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.334–26.123] and involvement of the paranasal sinus (P = 0.032, RR 3.137, 95% CI 1.105–8.908) adversely affect CNS involvement. In multivariate analysis, both were independently poor prognostic factors for CNS relapse [elevated LDH level: P = 0.011, hazard ratio (HR) 6.716, 95% CI 1.548–29.131; involvement of the paranasal sinus: P = 0.008, HR 3.784, 95% CI 1.420–10.083]. The survival duration of patients with CNS involvement was significantly shorter than that of the patients without CNS involvement (P = 0.009), with median overall survival of 7.60 months (95% CI of 4.92–10.28) versus 27.43 months (95% CI of 0.00–57.38), respectively.

Conclusions: Elevated LDH level and involvement of the paranasal sinus are two risk factors for CNS involvement in patients with PTCLs. Considering the poor prognoses after CNS relapse, prophylaxis should be considered with the presence of any risk factor.

Keywords: CNS disease, PTCL, prognosis, prophylaxis

introduction

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) are a heterogeneous group of malignancies derived from mature or post-thymic T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, representing ∼12% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) in Western countries [1]. However, in the Asian population, the incidence of the disease is known to be higher [2, 3]. Because of its rare incidence and the lack of standardized treatment strategies, the prognosis of the disease is worse than that of B-cell lymphomas and the natural course is not well-understood.

Many authors have reported the risk factors and the prognostic value of involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) in patients with B-cell lymphoma [4–6]. Patients with aggressive lymphomas such as lymphoblastic and Burkitt's lymphoma are at high risk for CNS involvement (30–50%), and routine CNS prophylaxis for these diseases is recommended. In aggressive NHLs, involved sites, including testis [7], paranasal sinus [8], breast [9] and bone marrow [10], are also known to affect the incidence of CNS involvement. Other clinical factors including the presence of B symptoms, high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), two or more extranodal involvements, advanced stage, low albumin level and young age are reported to have an adverse influence on CNS involvement [4]. The prognoses of patients with CNS disease are dismal, with a median survival of 2–6 months, which is even shorter than that of patients with non-CNS relapse [11].

With respect to PTCLs, few studies have reported on the incidence of CNS involvement [12, 13] and no study has suggested specific risk factors for CNS involvement in the disease. This lack of information may be attributed to the low incidence and various subtypes of PTCLs. However, as novel treatment strategies enable patients with PTCLs to survive longer, cases of CNS involvement may also be increasing in frequency. Therefore, identification of risk factors for CNS involvement in patients with PTCLs is necessary.

Recently, Kim et al. reported that the incidence of CNS involvement in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma was 5.76% and suggested that a high NK/T-cell lymphoma prognostic index (NKPI) score [14] could be a predictive factor [15, 16]. However NK/T cell lymphoma differs from other PTCLs in that it frequently originates from the oronasal or aerodigestive areas.

In this study, we carried out a retrospective analysis of the clinical features, predictive factors and prognostic role of CNS involvement in patients with PTCLs.

patients and methods

patients

Patients older than 15 years who were diagnosed with mature T-cell lymphoma from June 1995 to August 2009 were included in the analysis. Based on the World Health Organization classification for mature T-cell neoplasms, we included patients with PTCL, not otherwise specified (NOS), anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTL) and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL). All of the pathologic diagnoses were based on hematoxylin and eosin staining, and immunostaining for antigens such as CD3, CD4, CD30 and CD56. If needed, further analysis for T-cell receptor class or Epstein–Barr virus in situ hybridization can be carried out.

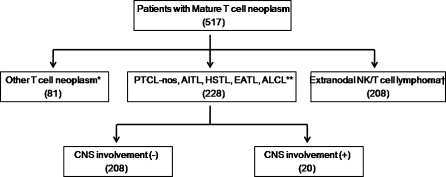

The following subtypes were excluded: T-cell leukemias, NK cell leukemia, lymphoblastic lymphoma, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous PTCLs, mycosis fungoides, Sezary syndrome and chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells. Among 517 patients with mature T-cell lymphoma, 228 patients were included in the analysis (Figure 1). This study was approved by the institutional review board of Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Program approved center. The study was carried out in accordance with the precepts of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1.

Patient cohort [*other T-cell neoplasms include other T-cell leukemias, natural killer (NK) cell leukemia, lymphoblastic lymphoma, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas, mycosis fungoides, Sezary syndrome and chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells; **PTCL-NOS, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; HSTL, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma; EATL, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; ALCL, anaplastic large cell lymphoma; †Kim et al. 20].

diagnosis of CNS disease

CNS disease was defined as any evidence of CNS involvement any time after initial diagnosis. CNS disease was divided into two categories; an isolated CNS involvement without evidence of systemic residual disease and combined involvement of CNS with other systemic involvement.

The types of CNS disease consisted of parenchymal metastases and leptomeningeal invasion. Parenchymal disease was diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or a brain computed tomography scan. Leptomeningeal involvement was diagnosed on the basis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology and three diagnostic criteria were applied. These criteria were (i) presence of malignant lymphomatous cells in the CSF, (ii) presence of suspicious cells with increased protein level in the CSF or (iii) presence of suspicious cells with suggestive findings of leptomeningeal seeding on MRI. The definition of suspicious cells was lymphocytes with an atypical morphology.

clinical parameters

We retrospectively collected clinical parameters from patients’ medical records, including age, sex, final pathologic diagnosis, date and the regimen of the first treatment, date of last visit or expiration, performance status (PS), Ann Arbor stage, presence of extranodal involvement, bone marrow involvement, paranasal sinus involvement or B symptoms and serum level of LDH. We calculated the prognostic models, international prognostic index (IPI) and prognostic index for PTCL-NOS (PIT).

statistical analysis

Time to CNS disease was defined as the time from the beginning of therapy to the diagnosis of CNS disease and was estimated from Kaplan–Meier curves. We carried out a log-rank test for univariate analysis of the other clinical parameters. A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered significant. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used in multivariate analysis to compare the factors proven to be statistically significant or to demonstrate a trend in the univariate analysis.

results

patient characteristics

The 228 patients had a median age 53 years (range 16–88), and 143 (62.7%) patients were male. With regard to histologic subtypes, 130 (57.0%) patients had PTCL-NOS, 52 (22.8%) had AITL, 32 (14.0%) had ALCL, 8 (3.5%) had EATL and 6 (2.6%) had HSTL. Among patients with ALCL, 11 were positive for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), 12 were negative for ALK and 9 were not examined for ALK status. The clinical parameters according to histologic subtype are summarized in Table 1. As for first-line treatment, 204 patients (89.5%) had received combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP) or CHOP-like therapy, 14 patients (6.1%) had received chemotherapy other than CHOP-like regimen and 10 patients (4.4%) had not received any kinds of definitive therapy. None of the patients had received CNS prophylaxis. Two patients who initially had CNS involvement at the time of diagnosis started IT MTX with fist-line systemic chemotherapy (CHOP).

Table 1.

Clinical parameters according to histologic subtype

| Histologic subtypes | PTCL-NOS (%) | ALCL (%) | AITL (%) | HSTL (%) | EATL (%) | Total (%) |

| Number of cases | 130 | 32 | 52 | 6 | 8 | 228 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 86 (66.2) | 20 (62.5) | 32 (61.5) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (50) | 143 (62.7) |

| Female | 44 (33.8) | 12 (37.5) | 20 (38.5) | 5 (83.3) | 4 (50) | 85 (37.3) |

| Age, median (years) | 52.5 | 36.5 | 58.5 | 36.5 | 51.5 | 53 |

| ≤50 | 59 (45.4) | 24 (75.0) | 9 (17.3) | 5 (83.3) | 4 (50.0) | 101 (44.3) |

| >50 | 71 (54.6) | 8 (25.0) | 43 (82.7) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (50.0) | 127 (55.7) |

| Clinical features | ||||||

| ECOG PS ≥ 2 | 34 (26.2) | 8 (25.0) | 21 (40.4) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (37.5) | 69 (30.3) |

| B symptom present | 68 (52.3) | 18 (56.3) | 34 (65.4) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (37.5) | 125 (55.8) |

| Serum LDH > UNL | 81 (62.3) | 14 (43.8) | 42 (80.8) | 2 (40.0) | 4 (50.0) | 143 (62.7) |

| Extranodal involvement > 1 | 33 (25.4) | 18 (56.3) | 26 (50.0) | 5 (83.3) | 4 (50.0) | 86 (37.7) |

| Bone marrow involvement | 42 (32.6) | 12 (38.7) | 28 (53.8) | 5 (83.3) | 0 (0.0) | 87 (38.2) |

| Paranasal sinus involvement | 22 (16.9) | 4 (13.3) | 5 (9.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 31 (13.6) |

| Ann Arbour stage | ||||||

| I/II | 36 (27.7) | 10 (31.3) | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 49 (21.5) |

| III/IV | 94 (72.3) | 22 (68.8) | 50 (96.2) | 6 (100) | 7 (87.5) | 179 (78.5) |

| First-line treatment | ||||||

| CHOP/CHOP-like regimen | 114 (87.6) | 27 (84.4) | 50 (96.2) | 5 (83.3) | 8 (100) | 204 (89.5) |

| Regimen other than CHOP | 8 (6.2) | 4 (12.5) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 14 (6.1) |

| No treatment | 8 (6.2) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (4.4) |

| Prognostic index | ||||||

| IPI risk | ||||||

| Low/low intermediate | 86 (66.2) | 19 (59.4) | 15 (28.8) | 3 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) | 128 (56.1) |

| High/high intermediate | 44 (33.8) | 13 (40.6) | 37 (71.2) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (37.5) | 100 (43.9) |

| PIT group | ||||||

| 1/2 | 71 (54.6) | 20 (62.5) | 13 (25.0) | 3 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) | 112 (49.1) |

| 3/4 | 59 (45.4) | 12 (37.5) | 39 (75.0) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (37.5) | 116 (50.9) |

PTCL-NOS, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; ALCL, anaplastic large cell lymphoma; AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; HSTL, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma; EATL, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; UNL, upper normal limit; CHOP, combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone; IPI, international prognostic index; PIT, prognostic index for PTCL-NOS.

clinical features of CNS disease

CNS involvement was observed in 20 out of 228 patients (8.77 %) during a median follow-up period of 13.9 months (range 0.03–159.43). The baseline characteristics of patients with PTCLs according to CNS involvement are described in Table 2. Among the histologic subtypes, ALCL had the highest proportion of CNS disease (5/32, 15.6%). Two patients were positive for ALK, two were negative and one was not examined for ALK status. None of the patients with HSTL (0/8, 0%) and a relatively small portion of patients with AITL (3/52, 5.8%) had CNS disease. However, there was no statistically significant difference among the histologic subgroups (P = 0.348).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients with PTCLs according to CNS involvement

| Without CNS involvement (%) | With CNS involvement (%) | |

| Number of cases (total N = 228) | 208 | 20 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 133 (63.9) | 10 (50.0) |

| Female | 75 (36.1) | 10 (50.0) |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤50 | 92 (44.2) | 9 (45.0) |

| >50 | 116 (55.8) | 11 (55.0) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| PS 0–1 | 148 (71.2) | 11 (55.0) |

| PS 2–4 | 60 (28.8) | 9 (45.0) |

| B symptom | ||

| Present | 93 (45.1) | 7 (35.0) |

| Absent | 113 (54.9) | 13 (65.0) |

| Serum LDH | ||

| ≤Upper normal limit | 82 (39.6) | 2 (10.0) |

| >Upper normal limit | 125 (60.4) | 18 (90.0) |

| Number of extranodal site involvement | ||

| 0–1 | 131 (63.3) | 10 (50.0) |

| 2 or more | 76 (36.7) | 10 (50.0) |

| Visceral organ involvement | ||

| Present | 71 (34.1) | 11 (55.0) |

| Absent | 137 (65.9) | 9 (45.0) |

| Bone marrow involvement | ||

| Present | 81 (39.1) | 6 (30.0) |

| Absent | 126 (60.9) | 14 (70.0) |

| Sinonasal area involvement | ||

| Present | 25 (12.0) | 6 (30.0) |

| Absent | 183 (88.0) | 14 (70.0) |

| Ann Arbour stage | ||

| I/II | 46 (22.1) | 3 (15.0) |

| III/IV | 162 (77.9) | 17 (85.0) |

| International prognostic index risk | ||

| Low/low intermediate | 115 (55.3) | 13 (65.0) |

| High/high intermediate | 93 (44.7) | 7 (35.0) |

| PIT group | ||

| 1/2 | 99 (47.6) | 13 (65.0) |

| 3/4 | 109 (52.4) | 7 (35.0) |

| Histologic subtype | ||

| PTCL-unspecified | 119 | 11 (8.5)a |

| ALCL | 27 | 5 (15.6)a |

| AITL | 49 | 3 (5.8)a |

| EATL | 7 | 1 (12.5)a |

| HSTL | 6 | 0 (0.0)a |

Among the same histologic subtype.

PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; CNS, central nervous system; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PIT, prognostic index for PTCL-NOS; ALCL, anaplastic large cell lymphoma; AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; EATL, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; HSTL, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma.

The clinical manifestations of CNS disease are summarized in Table 3. Fourteen (70.0%) patients had leptomeningeal involvement, five (25.0%) had parenchymal metastasis and one (5.0%) had both. Two (10.0%) patients had isolated CNS involvement and 18 (90.0%) had CNS disease along with another systemic disease. Both patients with isolated CNS involvement had parenchymal metastasis and among the 18 patients with combined CNS and systemic involvement, 14 had leptomeningeal seeding, 3 had parenchymal metastasis and 1 had both types of involvement.

Table 3.

Clinical manifestations of CNS disease

| Histologic subtypes | Total | PTCL-NOS | ALCL | AITL | EATL |

| Disease relationship between CNS and whole-body system | |||||

| Isolated CNS relapse | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| With systemic involvement | 18 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| The type of CNS disease | |||||

| Leptomeningeal seeding | 14 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Parenchymal metastasis | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Combined | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

CNS, central nervous system; PTCL-NOS, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; ALCL, anaplastic large cell lymphoma; AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; EATL, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.

The median time to CNS disease was 6.05 months (range 0.0–71.2). The clinical features of individual patients with CNS disease and their courses are summarized in Table 4. Two patients had CNS involvement at the time of initial diagnosis, 7 patients had recurring disease of the CNS after complete remission after systemic chemotherapy or autologous stem cell transplantation and 11 patients had CNS disease developed during the first-line or salvage chemotherapy with residual systemic disease.

Table 4.

The clinical features of individual patients with CNS relapse

| Sex | Age | Histology | Stage | Site of involvement | IPI risk | First-line therapeutic regimen | Disease status at the presentation of CNS disease | Time to CNS event (months) | Pattern | Therapy directed to CNS disease | CNS response | Survival after CNS disease (months) |

| CNS involvement without systemic residual disease | ||||||||||||

| M | 44 | PTCL-NOS | IVB | Testis | HI | CHOP#6 | CR after CHOP | 32.13 | P/I | RT/ASCT | CR | 13.3 |

| M | 43 | PTCL-NOS | IIIB | Temporal bone | LI | CHOP#6 | CR after CHOP | 6.37 | P/I | RT | CR | 100.5 |

| M | 43 | PTCL-NOS | IVB | Nasal cavity, testis | LI | CHOP#3 | CR after ASCT | 9.00 | L/S | IT | PD | 1.0 |

| M | 56 | PTCL-NOS | IIIA | Infraauricular mass | LI | CHOP#6 | CR after ASCT | 29.60 | L/S | IT/CT | CR | 12.1+ |

| F | 24 | PTCL-NOS | IVA | Ovary, lung, thyroid | HI | CHOP#3 | CR after ASCT | 12.40 | L&P/S | RT | PR | 3.9 |

| F | 57 | EATL | IIIA | Colon | LI | CHOP#4 | CR after salvage therapy | 7.7 | L/S | CT | NE | 0.3 |

| M | 59 | ALCL, ALK− | IIB | Nasal cavity | L | CHOP#2 | CR after CHOP | 3.53 | P/S | Not done | NE | 2.8 |

| CNS involvement with systemic residual disease | ||||||||||||

| M | 55 | AITL | IVB | Omentum, liver, BM | HI | CHOP#2/IT | Initial diagnosis | 0 | L/S | IT/CT | CR | 4.6 |

| M | 54 | PTCL-NOS | IVA | Colon, ileum, BM | HI | CHOP#2/IT | Initial diagnosis | 0 | L/S | IT/CT | CR | 3.1 |

| F | 52 | AITL | IIIB | Peritoneal, inguinal LN | LI | CHOP#6 | PD after salvage CT | 71.23 | L/S | CT | NE | 2.7 |

| F | 69 | ALCL | IIB | Epiglottis | LI | CHOP#4 | PD after salvage CT | 5.73 | L/S | RT | PD | 0.07 |

| F | 50 | AITL | IIIA | Infraauricular mass | LI | CHOP#1 | During salvage CT | 2.90 | P/S | RT/IT/CT | PD | 3.6 |

| F | 59 | PTCL-NOS | IVB | BM, neck LN | LI | CHOP#1 | During salvage CT | 1.43 | P/S | RT/CT/ASCT | CR | 100.1 |

| M | 38 | ALCL, ALK+ | IVA | Small bowel, lung | LI | CHOP#3 | During salvage CT | 8.03 | L/S | IT/RT | CR | 2.5 |

| F | 57 | PTCL-NOS | IIIA | Stomach | LI | CHOP#5 | PD after salvage CT | 6.97 | L/S | RT | PD | 0.3 |

| F | 31 | ALCL, ALK+ | IVB | Skin, liver, BM | H | CHOP#2 | During first-line CT | 1.03 | L/S | Not done | NE | 0.2 |

| F | 59 | ALCL, ALK− | IVB | Nasopharynx, lung | HI | CHOP#1 | During first-line CT | 2.17 | L/S | IT | NE | 0.3 |

| M | 31 | PTCL-NOS | IVB | Skin, liver | H | CHOP#2 | During salvage CT | 1.90 | L/S | Not done | NE | 0.5 |

| M | 60 | PTCL-NOS | IVB | Jejunum, rib | H | Bortezomib-CHOP#1 | During first-line CT | 0.6 | L/S | IT/CT | CR | 6.7+ |

| F | 21 | PTCL-NOS | IVB | Skin, BM | LI | CHOP#3 | During first-line CT | 1.97 | L/S | IT/ASCT | CR | 4.6 |

PTCL-NOS, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; EATL, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; ALCL, anaplastic large cell lymphoma; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma; kinase; AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; IPI, international prognostic index; HI, high intermediate risk group; LI, low intermediate risk group; L, low risk group; H, high risk group; CHOP, combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; PD, progressive disease; NE, not evaluated; CT, chemotherapy; RT, whole-brain radiation therapy; IT, intrathecal chemotherapy; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; P, parenchymal disease; L, leptomeningeal disease; I, isolated central nervous system (CNS) involvement; S, combined with systemic progression; BM, bone marrow; LN, lymph node.

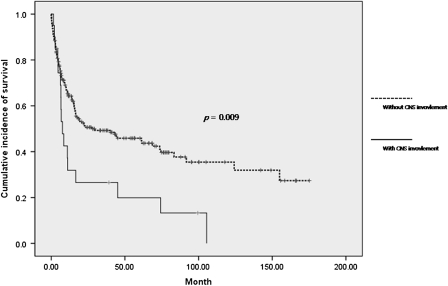

Survival of the patients with CNS involvement was significantly shorter than that of patients without CNS involvement (P = 0.009), with median overall survival of 7.60 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 4.92–10.28] versus 27.43 months (95% CI of 0.00–57.38), respectively (Figure 2). Two patients died from progression of CNS disease, 11 patients died of systemic progression and 7 patients were lost during follow-up.

Figure 2.

Overall survival according to central nervous system involvement.

risk factor analysis

An increased risk for CNS involvement was associated with increased LDH level [P = 0.015, relative risk (RR) 7.282, 95% CI 1.472–36.033] and involvement of the paranasal sinus (P = 0.029, RR 3.514, 95% CI 1.134–10.893) in univariate analysis. Risk factors of CNS involvement in B-cell lymphoma, such as bone marrow involvement, advanced age or Ann Arbor stage and extranodal involvement, did not increase the risk for CNS involvement in cases of PTCL (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate analysis for CNS involvement in patients with PTCLs

| RR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | |||

| Female | 1.773 | 0.706–4.455 | 0.223 |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≤50 | |||

| >50 | 0.969 | 0.385–2.438 | 0.947 |

| Serum LDH | |||

| ≤Upper normal limit | |||

| >Upper normal limit | 5.904 | 1.334–26.123 | 0.019 |

| B symptoms | |||

| Absent | |||

| Present | 1.528 | 0.586–3.988 | 0.386 |

| Ann Arbor stage | |||

| I/II | |||

| III/IV | 1.609 | 0.452–5.731 | 0.463 |

| Extranodal involvement | |||

| 0–1 | |||

| 2 or more | 1.724 | 0.686–4.329 | 0.247 |

| Visceral organ involvement | |||

| Absent | |||

| Present | 2.358 | 0.934–5.956 | 0.069 |

| PS | |||

| 0–1 | |||

| 2–4 | 2.018 | 0.796–5.118 | 0.139 |

| Paranasal sinus involvement | |||

| Absent | |||

| Present | 3.137 | 1.105–8.908 | 0.032 |

| Bone marrow involvement | |||

| Absent | |||

| Present | 0.667 | 0.246–1.805 | 0.425 |

| IPI | |||

| I/II | |||

| III/IV | 0.666 | 0.255–1.737 | 0.406 |

| PIT | |||

| III/IV | |||

| I/II | 0.489 | 0.188–1.275 | 0.143 |

CNS, central nervous system; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PS, performance status; IPI, international prognostic index; PIT, prognostic index for PTCL-NOS.

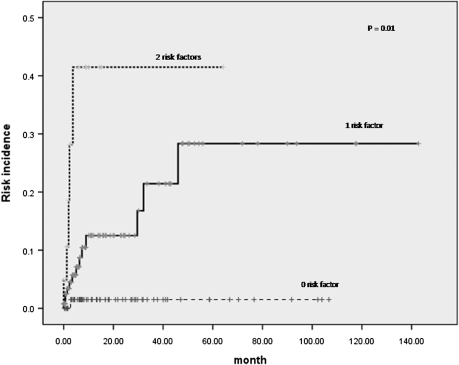

In multivariate analysis, both the increased LDH level [P = 0.011, hazard ratio (HR) = 6.716, 95% CI 1.548–29.131] and involvement of the paranasal sinus (P = 0.008, HR 3.784, 95% CI 1.420–10.083) were predictive factors for CNS disease. Comparing the patients with zero, one or two risk factors, the incidences of CNS involvement were significantly different among the groups (Figure 3). One out of 75 (1.3%) patients without any risk factor, 14 out of 132 (10.6%) patients with one risk factor and 5 out of 21 (23.8%) patients with both risk factors had CNS disease (P = 0.010).

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of central nervous system relapse according to number of the risk factors.

discussion

The risk of CNS involvement is 30–50% in patients with aggressive lymphomas such as lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia or Burkitt's lymphoma [17–19], and 5–10% in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [4].

In cases of PTCLs, there have been few reports of the incidence of CNS involvement, risk factors or prognostic role on overall survival. Kim et al. reported that 5.76% of secondary CNS involvement in patients with extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type and group III/IV NKPI [20] has statistical power to predict secondary CNS disease.

In our study, 20 out of 228 patients (8.77%) had CNS disease. Patients with ALCL had the highest incidence (5/32, 15.6%), and among 32 patients with ALCL, ALK status was examined in 23 patients. Twelve patients were ALK negative and 11 were ALK positive. Although ALK-positive ALCL is known to have a better prognosis, there was no difference in CNS involvement between the ALK-positive and ALK-negative groups (P = 0.924).

Patients with AITL had the least CNS involvement (3/52, 5.8%). In many cases, patients with AITL have advanced age, B symptoms, poor PS, elevated LDH and advanced stage, all of which are known to adversely affect the prognoses of the patients [21, 22]. However, according to our study, CNS involvement seems to be relatively rare in AITL. For cases of HSTL, which is also known to have an aggressive clinical course such as visceral organ/extranodal involvement or pancytopenia, there was no CNS involvement. As our study analyzed only six patients with HSTL, a larger clinical study is necessary to determine the CNS involvement with HSTL.

IPI and PIT have been applied to various kinds of PTCLs, and many have a reported prognostic value [3, 21, 23, 24]. In our study, however, neither IPI nor PIT was related to CNS disease, which may be the result of a lack of predictive roles of age, advanced stage, extranodal involvement, PS or bone marrow involvement. The known incidence of CNS involvement and risk factors according to histologic subtypes are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Published data of incidence and risk factors for CNS disease according to histologic subtype

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphomaa | Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphomab | PTCLc | |

| Incidence | 5–10% | 5.76% | 8.77% |

| Risk factors | Advanced age High IPI score Two or more extranodal involvement Paranasal sinus involvement Bone marrow involvement Testicular involvement | III/IV NKPI groupd Presence of B symptoms Advanced stage Elevated LDH level Regional lymph nodes involvement | Elevated LDH level Paranasal sinus involvement |

Blood Rev 2006; 20: 319–332.

Ann Oncol 2010; 21 (5): 1058–1063.

This study.

J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 612–618.

CNS, central nervous system; NK, natural killer; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; IPI, international prognostic index; NKPI, NK/T-cell lymphoma prognostic index; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

The median time to first CNS involvement in our study was 6.05 months (range 0.0–71.2 months). Using the results of previous reports, this is somewhat shorter than that of the B-cell lymphomas (5–12 months [4]) and is similar to that of extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type (6.03 months [20]).

Seven patients had CNS disease that relapsed without evidence of systemic residual disease. The longest disease-free interval between systemic remission and CNS relapse was 32.13 months, where the primary disease was PTCL-NOS in testis. Another patient with testis involvement of PTCL-NOS had CNS relapse after 9 months of complete remittance. Of 228 patients, three had testicular involvement and two had CNS disease. This suggests that the testis could also be a sanctuary area against systemic chemotherapy and therefore should be considered a high-risk site for CNS relapse in PTCLs, as in the case of B-cell lymphomas. A larger analysis is required to further analyze this as a factor.

The median survival duration of patients with CNS disease was significantly shorter than that of patients without CNS disease. Among 13 patients with CNS disease whose clinical courses were followed up, 11 patients died of systemic progression and only two died of CNS progression. CNS relapse might be a manifestation of systemic progression, or untreated malignant lymphocytes could remain in the brain parenchymal tissue or CSF.

Fourteen out of 132 (10.6 %) patients with either risk factor (elevated LDH level, paranasal sinus involvement) and 5 out of 21 (23.8%) patients with both risk factors had CNS involvement. This implies that screening and follow-up examinations for CNS involvement should be considered in patients with any risk factor, although there is no consensus on efficacy, what therapeutic agents or methods should be used for the treatment [4]. Further large-scaled analysis is necessary on this issue.

In summary, elevated serum LDH level and involvement of the paranasal sinus are risk factors for CNS involvement in patients with PTCLs. CNS prophylaxis might be considered for patients with any risk factors although it is not clear what the treatment option should be.

funding

This study was supported by research grants from the Samsung Biomedical Research Institute (CA-A9-208) and the Korea Health 21 R&D Project (A090224).

disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.O'Leary H, Savage KJ. The spectrum of peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16:292–298. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32832b89a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim K, Kim WS, Jung CW, et al. Clinical features of peripheral T-cell lymphomas in 78 patients diagnosed according to the Revised European-American lymphoma (REAL) classification. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:75–81. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko OB, Lee DH, Kim SW, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of T-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a single institution experience. Korean J Intern Med. 2009;24:128–134. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2009.24.2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill QA, Owen RG. CNS prophylaxis in lymphoma: who to target and what therapy to use. Blood Rev. 2006;20:319–332. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrlinger U, Glantz M, Schlegel U, et al. Should intra-cerebrospinal fluid prophylaxis be part of initial therapy for patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma: what we know, and how we can find out more. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:S25–S34. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Besien K, Gisselbrecht C, Pfreundschuh M, Zucca E. Secondary lymphomas of the central nervous system: risk, prophylaxis and treatment. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(Suppl 1):52–58. doi: 10.1080/10428190802311458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zucca E, Conconi A, Mughal TI, et al. Patterns of outcome and prognostic factors in primary large-cell lymphoma of the testis in a survey by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:20–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laskin JJ, Savage KJ, Voss N, et al. Primary paranasal sinus lymphoma: natural history and improved outcome with central nervous system chemoprophylaxis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:1721–1727. doi: 10.1080/17402520500182345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aviles A, Delgado S, Nambo MJ, et al. Primary breast lymphoma: results of a controlled clinical trial. Oncology. 2005;69:256–260. doi: 10.1159/000088333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto W, Tomita N, Watanabe R. Central nervous system involvement in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 2010;85:6–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein SH, Unger JM, Leblanc M, et al. Natural history of CNS relapse in patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a 20-year follow-up analysis of SWOG 8516—the Southwest Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:114–119. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Guillermo A, Cid J, Salar A, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphomas: initial features, natural history, and prognostic factors in a series of 174 patients diagnosed according to the R.E.A.L. Classification. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:849–855. doi: 10.1023/a:1008418727472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savage KJ, Chhanabhai M, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM. Characterization of peripheral T-cell lymphomas in a single North American institution by the WHO classification. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1467–1475. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seo HI, Park SJ, Kim SH, et al. Analysis of 50 consecutive hepatic resection cases for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;10:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollender A, Kvaloy S, Nome O, et al. Central nervous system involvement following diagnosis of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a risk model. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1099–1107. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boehme V, Zeynalova S, Kloess M, et al. Incidence and risk factors of central nervous system recurrence in aggressive lymphoma–a survey of 1693 patients treated in protocols of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL) Ann Oncol. 2007;18:149–157. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buckstein R, Lim W, Franssen E, Imrie KL. CNS prophylaxis and treatment in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: variation in practice and lessons from the literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:955–962. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000067909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sariban E, Edwards B, Janus C, Magrath I. Central nervous system involvement in American Burkitt's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1:677–681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.11.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SJ, Oh SY, Hong JY, et al. When do we need central nervous system prophylaxis in patients with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type? Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1058–1063. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park BB, Ryoo BY, Lee JH, et al. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:716–722. doi: 10.1080/10428190601123989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mourad N, Mounier N, Briere J, et al. Clinical, biologic, and pathologic features in 157 patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma treated within the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte (GELA) trials. Blood. 2008;111:4463–4470. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-105759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallamini A, Stelitano C, Calvi R, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma unspecified (PTCL-U): a new prognostic model from a retrospective multicentric clinical study. Blood. 2004;103:2474–2479. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzumiya J, Ohshima K, Tamura K, et al. The International Prognostic Index predicts outcome in aggressive adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma: analysis of 126 patients from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:715–721. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]