Abstract

Polyamines have been globally associated to plant responses to abiotic stress. Particularly, putrescine has been related to a better response to cold and dehydration stresses. It is known that this polyamine is involved in cold tolerance, since Arabidopsis thaliana plants mutated in the key enzyme responsible for putrescine synthesis (arginine decarboxilase, ADC; EC 4.1.1.19) are more sensitive than the wild type to this stress. Although it is speculated that the overexpression of ADC genes may confer tolerance, this is hampered by pleiotropic effects arising from the constitutive expression of enzymes from the polyamine metabolism. Here, we present our work using A. thaliana transgenic plants harboring the ADC gene from oat under the control of a stress-inducible promoter (pRD29A) instead of a constitutive promoter. The transgenic lines presented in this work were more resistant to both cold and dehydration stresses, associated with a concomitant increment in endogenous putrescine levels under stress. Furthermore, the increment in putrescine upon cold treatment correlates with the induction of known stress-responsive genes, and suggests that putrescine may be directly or indirectly involved in ABA metabolism and gene expression.

Key words: cold acclimation, dehydration, putrescine, polyamines, stress

Introduction

Polyamines are organic polycations widely distributed in all organisms. The diamine putrescine can be synthesized by ornithine decarboxylase (ODC; EC 4.1.1.17) or arginine decarboxylase (ADC; EC 4.1.1.19) pathways. After putrescine synthesis, aminopropyl groups are added sequentially to form the triamine spermidine and the tetramine spermine, catalized by the enzymes Spermidine synthase (SPDS; EC 2.5.1.16) and Spermine synthase (SPMS; EC 2.5.1.22) respectively.1,2

There is evidence for the involvement of putrescine, spermidine and spermine in a vast number of biological processes.2–5 However, their precise role in plant physiology still remains unclear.1 One of the most remarkable metabolic phenomena of polyamines is their dramatic change in concentration upon response to adverse environmental cues.6 In this regard, polyamines have been proposed to act as radical scavengers,7,8 as regulators of K+ channels in stomata9 and as compatible solutes.10 Stresses that lead to an increase in putrescine include K+ deficiency, ammonium nutrition, exposure to low pH, osmotic stress, cadmium and SO2 toxicity, UV-B radiation,3,8,11,12 and pathogen infections.13 ADC has been recognized as the key enzyme of polyamine metabolism in plant response to biotic and abiotic stress.8,14–16 Several environmental stresses induce ADC mRNA expression and enzyme activity in a diverse number of species.10 In the plant kingdom, to date, only Arabidopsis thaliana is the known exception lacking the ODC pathway,17 but this species display two ADCs genes (AtADC1 and AtADC2) which have been cloned and characterized. AtADC1 is highly expressed in roots and leaves of plants subjected to chilling, whereas light, sucrose and ethylene are important regulators of AtADC2 expression.18 AtADC2 (but not AtADC1) is also related to osmotic response and ABA treatment.16,19–21 Moreover, A. thaliana plants under cold stress present high AtADC1 and AtADC2 expression and increased putrescine levels, and mutants in these genes are impaired in their survival to freezing stress which reverts after the addition of putrescine in the growth media.21,22

The isolation of genes coding for polyamine biosynthetic enzymes allowed the genetic manipulation of polyamine metabolism.1,2,23 However, because overexpression of these genes under the control of a constitutive promoter render phenotypic alterations induced by over-accumulation of polyamines,24,25 the use of inducible promoters has become an important tool.26 In order to understand how putrescine levels are involved in the response to different abiotic stresses, we obtained transgenic plants overexpressing the ADC from oat under the control of the A. thaliana stress-inducible promoter pRD29A.27 The pRD29A promoter presents DRE (drought responsive element) and ABRE (ABA responding element) cis-acting elements which enable high and efficient induction under ABA, dehydration, high-salinity and low-temperature. These pRD29A:oat ADC transgenic plants were compared to the wild-type (WT) under dehydration, cold and freezing stresses. Here, we show that endogenous Putrescine levels affect the response of these plants to environmental stresses and how this polyamine potentially modulates ABA-dependent responses.

Results

Putrescine accumulation enhances dehydration tolerance.

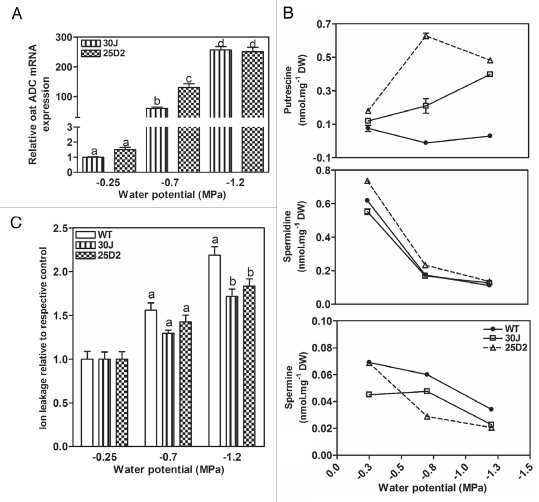

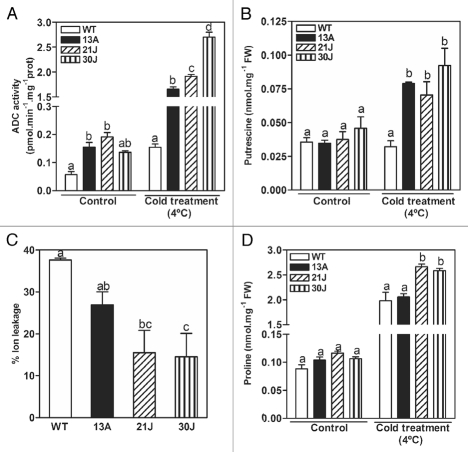

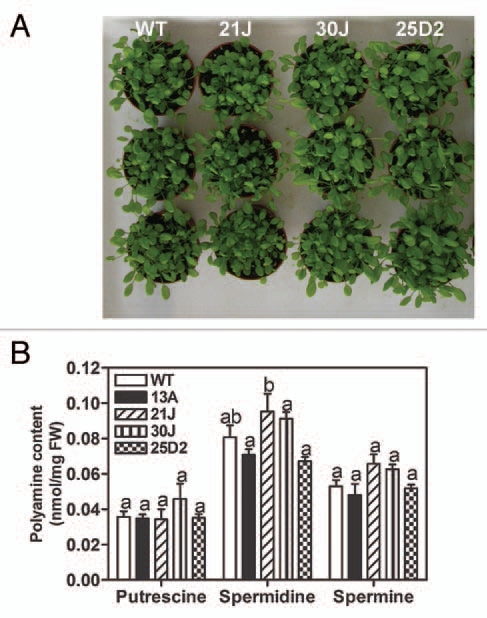

Transgenic A. thaliana plant harboring a pRD29A::oatADC construct were obtained, and four independent lines were selected for further work based on high ABA-inducible ADC activity (unpublished results). These transgenic lines did not present phenotypic differences in germination, vegetative growth or development compared to the wild type plants, in contrast to constitutive overexpression lines (Fig. 1A).28 In addition, putrescine, spermidine and spermine content of the transgenic lines were similar to WT under control conditions (Fig. 1B). Upon dehydration treatment (decreased water potential using different concentrations of PEG), oat ADC expression was induced and putrescine content was higher in the transgenic lines when compared to WT in the stress conditions (Fig. 2A and B). On the other hand, spermidine and spermine levels decreased in both WT and pRD29A::oatADC upon decreased water potential (Fig. 2B). Electrolyte leakage measurements were performed to assess the vitality of the treated plants and a higher damage in WT seedlings was observed, particularly at −1.2 MPa (Fig. 2C). The dehydration tolerance of pRD29A::oatADC transgenic plants thus matched with the higher expression of oat ADC and putrescine accumulation (Fig. 2A and B). As a whole, these data support the notion that putrescine accumulation is involved in the better performance of the transgenic lines.

Figure 1.

Phenotipic comparison between WT and transgenic plants. WT and transgenic lines were soil-grown under normal conditions during 21 days for visual observation (A). Polyamine content in control conditions (B) was determined. The same letter means no significant difference into each group (putrescine, spermidine or spermine).

Figure 2.

WT and transgenic A. thaliana seedlings under water potential stress. Eleven-day-old plate-grown seedlings were transferred to plates imbibed with different PEG solutions in order to modify medium water potential. After 13 h of treatment, seedlings were harvested for real-time RT-PCR quantification of oat ADC expression in transgenic plants (A), free polyamine detremination (B) and electrolyte leakage measurements (C). Control and treated samples were harvested at the same time. At −0.25 MPa is the normal water potential a medium presents. ND; not detected. The same letter means no significant difference into each group (−0.25, −0.75 or −1.2 MPa). As at −0.25 MPa there were no significant difference between WT and the transgenic lines (p > 0.05), data is presented as % ion leakage relative to corresponding control in order to better visualize the difference at higher water potential.

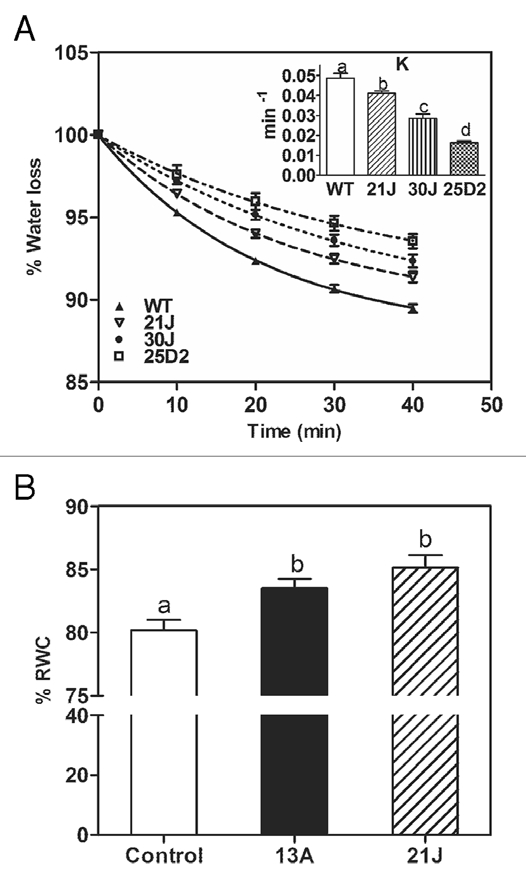

Since decrease in stomatal conductivity is an important trait under drought and polyamines were suggested to control stomatal movement,9,29 we also estimated the relative differences in transpiration between adult WT and transgenic plants grown in soil under control greenhouse conditions (Fig. 3A). Transpiration in transgenic pRD29A::oatADC lines was lower than in WT plants, implying that putrescine may also act in water saving traits at the whole plant level. Supporting this idea, relative water content in transgenic lines was higher than the wild-type (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Water lost percentage (A) and relative water content percentage (B) in WT and transgenic lines. Four similar shape and weight rosettes from each line were detached from 21-day-old soil-grown plants and placed in plates with their abaxial face up. Weight was measured every 10 min, considering 100% of water content related to the first weight measured. In an info graph the K value is compared, showing significant difference between WT and the transgenic lines, meaning that the transgenic lines are loosing less water. Five plates were measured for each line. K, decay constant.

Putrescine accumulation enhances freezing tolerance.

It is known that putrescine levels are involved in plant cold acclimation21,22 and that tolerance to severe dehydration is a critical factor in tolerance to freezing because both share similar signaling pathways.30,31 Thus, we also tested our pRD29A::oatADC transgenic lines under cold and freezing stress. Soil-grown transgenic plants acclimated for 10 days at 4°C presented cold-induced oat ADC activity and more putrescine than non-stressed and WT plants (Fig. 4A and B). When cold-induced damage was determined in acclimated-freezed plants, the transgenic lines suffered less membrane damage than the WT (Fig. 4C). In addition, the compatible osmolyte proline increased in WT and transgenic plants under cold acclimation, but the response was more pronounced in the transgenic 21J and 30J lines (Fig. 4D), in agreement with their better performance upon cold treatment.32

Figure 4.

Cold-induced oat ADC activity (A), free putrescine content (B), freeze-induced membrane damage (C) and proline content (D) in WT and transgenic plants grown in soil. 21-day-old soil-grown WT and transgenic plants were transferred to 4°C room for 10 days under long day growth conditions. After this time, samples were taken for ADC activity assay, free Putrescine determination, proline determination and freezing stress and ion leakage measurements. Control samples were taken before plants were subject to cold acclimatizing. The same letter means no significant difference into each group (control or 4°C acclimated).

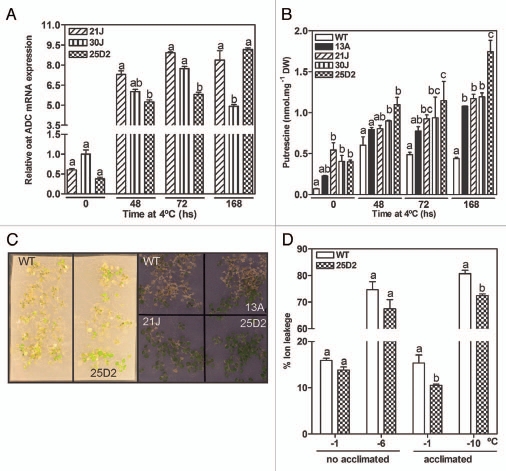

To further explore this behavior, transgenic and WT seedlings grown on plates were subjected to freezing stress in a programmable chamber in order to avoid the effects of humidity evaporation over the plant performance. In order to characterize the system, oat ADC expression was assayed for cold acclimated transgenic plants at different time points (0, 48, 72 and 168 h; Fig. 5A). Gene expression increased with the time of treatment and correlated with an increase in putrescine levels (Fig. 5B). Since this was higher for line 25D2, this line was used for further experiments. Under these conditions, we recorded the electrolyte-leakage at the lower temperature at which differences in survival were visually evident between WT and pRD29A::oatADC lines (−6°C for non-acclimated and −10°C for acclimated plants, Fig. 5C). Differences were not significant between non-acclimated WT and 25D2 seedlings (Fig. 5D). However, pre-acclimated 25D2 suffered less freezing-induced damaged than the WT (Fig. 5D). These measurements correlated with the visual observation of these plants (Fig. 5C) and with the fact that the transgene is been actively expressed after 48 h at 4°C (Fig. 5A). This was in line with the higher putrescine levels for the transgenic lines (Fig. 5B). Spermidine and spermine levels decreased for both WT and transgenic lines (data not shown),22 implying that the better performance of this plant under freezing stress is due to a higher accumulation of putrescine.

Figure 5.

Cold-induced oat ADC expression (A), free putrescine content (B) and freeze-induced membrane damage (C and D) in WT and transgenic seedlings grown in plates. Eleven days old seedlings were cold-acclimatized for several times (0, 48, 72 and 168 hs) and subjected to programmed freezing treatment with or without 4°C pre-acclimatizing for 48 hs. The temperature −6°C was the lower temperature selected for no-acclimated plates, while −10°C was selected for the acclimated ones. (C) Visual observation.

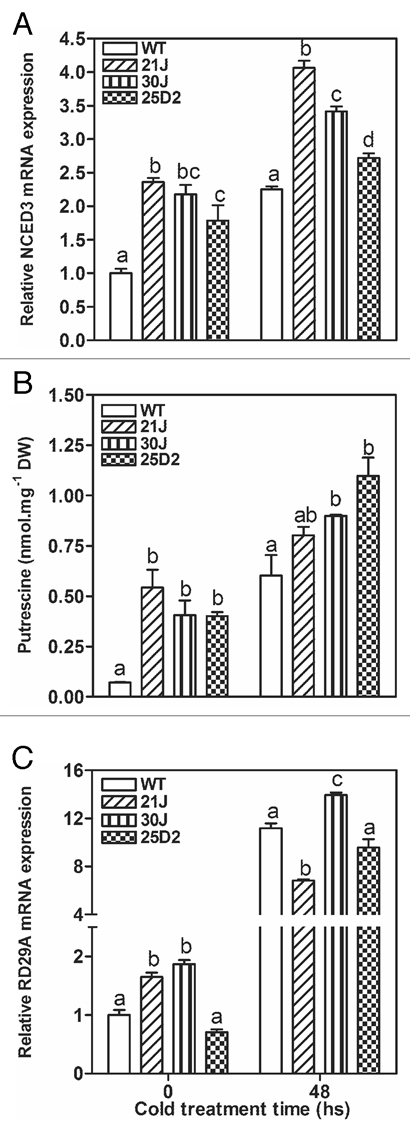

Cold acclimation increases RD29A and NCED3 activation.

The phytohormone ABA is associated with a positive response of plants to cold stress,31,33 and the expression of the key gene controlling ABA-synthesis under stress, AtNCED3, is directly or indirectly modulated by putrescine in response to cold.21,22 In addition, genes from the COR operon such as AtRD29A, are know markers of the plant response to cold stress.31,34 The expression levels of AtNCED3 and AtRD29A genes were determined in WT and pRD29A::oatADC transgenic plants grown in petri dishes under control or 48 h of cold stress treatments (Fig. 6). AtNCED3 basal expression was higher in transgenic lines compared to WT, but after cold acclimation all plants induced the expression of this gene (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, the expression of AtNCED3 in 21J, 30J and 25D2 lines correlated with a major increase in free endogenous putrescine (Fig. 6B), supporting a putrescine-mediated induction of ABA biosynthesis.21,22 AtRD29A expression was induced by chilling in both WT and pRD29A::oatADC plants in different degrees (Fig. 6C), confirming that the stress-signaling pathways are not disrupted in the transgenics accumulating more putrescine.

Figure 6.

Real-time RT-PCR quantification of NCED3 (A) and RD29A (C) expression and free Putrescine content (B) in WT and transgenic seedlings after 48 h of cold treatment. Eleven-day-old WT and transgenic seedlings were subjected to 48 h cold-stress at 4°C in long day conditions. Samples were harvested at the beginning of treatment (time 0) and after 48 h of treatment (time 48). real-time RT-PCR was performed considering EF-1 as house-keeping gene. The same letter means no significant difference into each group (0 or 48 h).

Discussion

In this work, the advantages of using a stress-inducible transgene to modulate an essential metabolic pathway have been demonstrated, as none of the transgenic pRD29A::oatADC lines presented phenotypic differences when compared to the WT under control growth conditions in germination, vegetative growth or development. In contrast to data reported previously on transgenic plants constitutively overexpressing ADC activity, which presented dwarfism and late flowering,28 our lines did not show any aberrant phenotype when ADC activity was induced and putrescine was accumulated. It is worthy to note that under our experimental conditions, sometimes some of the transgenic lines presented higher ADC activity than WT under control conditions. When analyzing polyamines content, putrescine was accumulated upon induction of ADC activity by osmotic and cold stresses in all the transgenic lines investigated. Interestingly, there were not significant differences in higher polyamines content when compared to WT under control or treatment conditions.

A higher relative water content percentage (%RWC) has been observed in at least two of the pRD29A::oatADC lines. So, it could be speculated that the transgenic plants display a more efficient usage of water than the WT, and this could be an advantage under dehydration stress. Accordingly, a transpiration assay showed that transgenic lines 30J and 25D2 lost less water. These plants also presented a higher putrescine accumulation after ABA treatment (not shown). The fact that these lines transpire less than the WT would indicate a higher stomata closure.35 In this regard, it is known that polyamines are capable of regulate stomata opening and inhibit KAT1 channel, preventing the K+ influx in the guard cells.9 It has also been shown that elevated Putrescine levels induced stomata closure in transgenic lines constitutively overexpressing the ADC2 gene,6,35 in total agreement with the results published here.

Finally, in the literature exists several reports that indicate that osmotic stress is a strong inductor of ADC activity and putrescine accumulation in different plant species.36,37 Data obtained from stressed plants supplemented with putrescine, and by diminutions of vitality due to the addition of putrescine analogues and/or ADC and ODC inhibitors,8,10,38 suggest the importance of this metabolic response. Moreover, A. thaliana adc2 mutants are hypersensitive to salt shock,39 while transgenic plants overexpressing ADC activity and accumulating higher putrescine levels had a better physiological performance upon salt shock and drought stress.26,35,40 In the transgenic plants studied in this work, a decrease in the water potential induced ADC activity and putrescine accumulation, leading to a better dehydration tolerance than the WT. In contrast to Yamaguchi et al. and Shi et al. who reported that Spermine (instead of putrescine) would be the polyamine with a protective role under dehydration stress, in our experiments both spermidine and spermine levels decreased in WT and pRD29A::oatADC lines (unpublished results). These data imply that putrescine (but not spermine) could be the polyamine responsible for the better performance observed under our experimental conditions. It is important to note that differences between reports could arise due to differential stress treatment or growing environment. Contrary to our experimental design, Yamaguchi et al.41 assayed a very fast and extreme dehydration stress.

Numerous publications link ABA metabolism with a better tolerance of plants to cold stress.6,21,22,31,33 In addition, AtNCED3 overexpression increase ABA content and reduces stomata conductivity.42–44 These observations are in agreement with the differential expression of AtNCED3 and AtRD29A in our pRD29A::oatADC lines under cold stress, also previously reported in WT and adc mutants supplemented with putrescine.21,22 Therefore, it could be speculated that putrescine may modulate at least the first steps of ABA metabolism, thus contributing to ABA-mediated tolerance. Further research aimed in unraveling this point is warrant.

There are several reports demonstrating that cold stress determinate an increment in putrescine and spermine content, along with induction of ornithine-, arginine- and S-adenosyl-methionine decarboxylase activities.10,45–49 Furthermore, A. thaliana ADC1 gene (but not ADC2) is induced under low temperature conditions.18 In our experiments, induction of ADC activity and putrescine accumulation were observed in 10-day, cold-acclimated plants, and those plants that accumulated higher putrescine levels presented lower membrane damage and a better survival under freezing stress. Thus, higher levels of putrescine represent a tolerance trait (insofar they are within physiological range, in our case achieved with a stress-inducible promoter instead of a constitutive one). These results are in agreement with previous reports showing that A. thaliana adc mutants are impaired in freezing tolerance, which is restored by exogenous putrescine application.22 The technological application of these observations in other plant species of agronomic interest is currently under evaluation in our laboratory.

Materials and Methods

Plant material and growth conditions.

Seeds of the A. thaliana gl-1 mutant were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC, Ohio State University, OH). Because all oat ADC transgenic plants were obtained in the gl-1 background, this mutant was used as WT control. Binary vectors harboring oat-ADC-encoding sequences under the control of the stress-inducible promoter pRD29A50 were used to transform A. thaliana plants by floral dip. Seeds were selected with kanamycine till the third generation. Four independent lines harboring the pRD29A::oatADC construction (13A, 21J, 30J and 25D2) were selected at random for further experimentation. Transgenesis was confirmed by PCR and by Southern Blot analysis.

Seeds were directly sown in pots filled with soil:sand:perlite (2:1:1) Plants were sub-irrigated with half-strength Hoagland's nutrient solution. Experiments with seedlings were performed growing plants in vitro for 12 days (post-imbibitions) on a polyester mesh (33 µm opening, 40 µm fiber diameter; Bückmann GmbH, Germany) in half-strength MS medium at pH 5.7 and including vitamines and 1 g/l MES (Duchefa Biochemie). All seeds were stratified at 4°C for 48 h before transferring to a growth room with a 16/8 h photoperiod at 24 ± 2°C, 50/75 ± 5% RH (day/night) and a photon flux density of 100 µmolm−2s−1 provided by day-light and grolux® fluorescent lamps.

Treatments.

Low water potential was applied as described by Verslues et al.30 with a few modifications. Ten-day-old seedlings were grown in vitro and transferred to plates with different water potential. Before transfer, the plates were equilibrated overnight with 50 ml of the appropriate PEG-8000 (Sigma) solution (0, 250, 400, 550, 700 g/l for −0.25, −0.5, −0.7, −1.2 and −1.7 MPa, respectively). The seedlings were harvested after 13 h of treatment.

Transpiration percentage was determined as follows. 21-day-old plant-rosettes grown on soil were cut off and placed in Petri dishes with their abaxial face up (four similar sized rosettes/plate). Plates were opened when the assay began, and weight was measured every ten min. 100% of water content was related to the first weight measured at time 0. Five dishes were measured for each genotype.

Relative water content51 was expressed as percentage, and was determined according to the following equation:

where FW, DW and TW means fresh weight, dry weight and weight at maximum turgent, respectively. DW was determined drying the plant material at 60°C for at least three days. TW was determined in leaves floating in distilled water on petri dishes for 24 h, once its FW was known.

For cold acclimation in whole plant, 3-week-old plants grown on soil were transferred for 10 days to a cold room at 4 ± 1°C (canopy level), 90 ± 5% RH with a long day photoperiod and a dim light. For cold acclimation in seedlings, 10-day-old seedlings were transferred to a cold room at 4 ± 1°C for different periods of time under the same light and photoperiodic conditions.

For freezing stress in pots, non-acclimated and 10-day-acclimated plants were subjected to −20°C for 30 minutes in the dark. Then they were restored back to normal conditions during two days before the assays were performed (25°C, 16 h light). Freezing assays in plates were carried out in a temperature programmable freezer. Non-acclimated or cold-acclimated (48 h, 4°C) 12- to 14-day-old seedlings were transferred to the programmable freezer set at −1°C. After 1–2 hs the plates were sprinkled with ice chips and maintained at −1°C for at least 16 h. Temperature was lowered with a rate of 1°C/h and plates were removed (−6°C for non-acclimated and −10°C for acclimated plants). After removal the plates were maintained in the dark at 4°C for 12 to 20 h for thawing.30 The polyester mesh with plants was transferred to a new medium and returned to the original growth conditions. Tolerance to freezing was determined by electrolyte leakage test30 and by visual observation.

ADC activity.

Arginine decarboxylase activity was measured by quantifying the 14CO2 released employing [U-14C]-L-arginine as substrate.52 500 mg of vegetal tissue were homogenized with morter and pestle in 1 ml of extraction buffer pH 7.5 (100 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.5, 20 mM sodium ascorbate, 5 mM EDTA, 0.4 mM PMSF, 1 µl/ml β-mercaptoethanol, 50 µM PLP, PVP and PEG-8000). 190 µl of supernatant were assayed in a reaction mix containing 10 mM L-arginine, 1 mM urea and 50 nCi [U-14C]-L-arginine (Amersham, 1.85 MBq, 50 µCi) in a final volume of 200 µl. After 45 min at 37°C, the reaction was stopped with 1 ml 10% v/v perchloric acid and the 14CO2 released was trapped in absorbent paper imbibed in 2 M KOH. Radioactive emission was measured in a Beckman LS 5000 TD scintillation counter. Protein content was determined by Bradford's method, using bovine serum albumin as the reference standard.53

Polyamine determination.

Free polyamines were quantified analyzing their dansyl-derivatives by HPLC whereas proline was determined spectrophotometrically by the ninhydrin reaction, both as described by Maiale et al.54

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis.

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction with some modifications. Briefly, the samples (seedlings or stem and leaves) were homogenized with morter and pestle in 1 ml TRIzol. The homogenate was collected in a 0.5 ml tube and 200 µl chloroform was added. After hand-shaking and centrifugation, the aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh RNAse free tube where RNA was precipitated with 0.5 ml isopropanol. The pellet was washed with ethanol 75% v/v, resuspended in 40 µl milliQ-RNAse free water and re-purified with Total Quick RNA Cells and Tissues columns according to manufacturer's instructions (Talent). The purified RNA was treated with TURBO DNA-free (Ambion) according to manufacturer's instructions to remove contaminating genomic DNA. A total of 2 µg of RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA with random hexamers using SuperScript™ III RT (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed on the ABIPrism® 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) and Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was used to amplify and detect the cDNA. The reaction mix for each well was 1 µl cDNA (1/10), 10 µl specific primers mix (FW and REV) and 12.5 µl Master Mix in a final volume of 25 µl. UBQ-10 (At4g05320) or EF-1 (At2g18720) were used as housekeeping genes to normalize the expression data. The PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s and 60°C for 1 min. Three replications were performed for each sample in each experiment. Data were analyzed using the DART-PCR Version 1.0 datasheet as described by Peirson et al.

The following primer sequences were used (FW and REV): 5′-AGT TAC GAC GTG AAA CAG GAT ATC A-3′ and 5′-CCA CCA TTT CCC ACA CCT TA-3′ (oat ADC; 300/900 nM), 5′-GAA GTT TGC TTC AAT GCT AGG TTA CTC-3′ and 5′-TCG TCA CGG CAG ACT CTG TT-3′ (RD29A; 250/250 nM; 2 mM MgCl2 added), 5′-AAA GCC ATC GGT GAG CTT CA-3′ and 5′-GCA GCT CTG GCG TAG AAT AGC-3′ (NCED3; 250/250 nM), 5′-TTG ACA GGC GTT CTG GTA AGG-3′ and 5′-CAG CGT CAC CAT TCT TCA AAA A-3′ (EF-1, 250/250 nM), 5′-TAA TCC CTG ATG AAT AAG TGT TCT AC-3′ and 5′-AAA ACG AAG CGA TGA TAA AGA AG-3′ (UBQ-10; 300/900 nM).

Electrolyte leakage test.

The electrolyte leakage test to determine stress induced damage in seedlings or leaves was performed according to Verslues et al. Briefly, seedlings were transferred to a tube containing 10 ml of milliQ water and were incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Then conductivity of the solution was measured in each tube before and after autoclaving the system for 20 min. Percentage of electrolyte leakage was calculated according to the following equation:

When low water potential-induced damage was analyzed, the seedlings were pre-treated as follow: the seedlings and mesh were lifted off of the plate and rinsed twice (5 s) with 5 ml of mannitol solutions of the same water potential as the PEG-infused plates (18.2, 36.4, 54.7, 87.5 and 120.4 g/l mannitol for −0.25, −0.5, −0.7, −1.2 and −1.7 respectively). After that, mesh and seedlings were gently blotted on Tissue paper and transferred to the tube containing milliQ water.

For freezing-induced damaged, the seedlings and mesh were transferred to the tube containing milliQ water after thawing (12 to 20 h at 4°C in dark) and the 2 h incubation in the milliQ water was performed at 4°C in dark.

Statistical analysis.

ANOVA with Bonferroni's post test analysis and t-test were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, USA).

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Dr. Ricardo Di Masso (Cátedra de Genética Experimental, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional de Rosario) for his invaluable assistance on statistical analysis. This work was supported by grants PICT of Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCYT, Argentina), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET, Argentina), San Martin University (UNSAM) and AECI (Spanish International Cooperation Agency) to O.A.R. and grants BIO2005-09252-C02-01 and BIO2008-05493-C02-01 to A.F.T. A.F.T, T.A., P.C. and O.A.R. also acknowledge grants-in-aid from COST-Action FA0605. M.E.G. and F.D.E. are fellows of CONICET (Argentina). O.A.R. is member of the research committee from CONICET (Argentina).

Abbreviations

- ABA

abscisic acid

- ADC

arginine decarboxylase

- DW

dry weight

- FW

fresh weight

- HPLC

high-pressure liquid chromatography

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SD

standard deviation

- %RWC

relative water content percentage

References

- 1.Kusano T, Berberich T, Tateda C, Takahashi Y. Polyamines: essential factors for growth and survival. Planta. 2008;228:367–381. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill SS, Tuteja N. Polyamines and abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2010;5:26–33. doi: 10.4161/psb.5.1.10291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galston AW, Sawhney RK. Polyamines in plant physiology. Plant Physiol. 1990;94:406–410. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.2.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slocum RD. Tissue and subcellular localization of polyamines and enzymes of polyamines metabolism. In: Slocum RD, Flores HE, editors. Biochemistry and physiology of polyamines in plants. Boca Raton: CRS Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galston AW, Flores HE. Polyamines and plant morphogenesis. Boca Raton: CRS Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alcázar R, Altabella T, Marco F, Bortolotti C, Reymond M, Koncz C, et al. Polyamines: molecules with regulatory functions in plant abiotic stress tolerance. Planta. 2010;231:1237–1249. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen SS. A guide to the polyamines. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flores HE. Changes in polyamine metabolism in response to abiotic stress. In: Slocum RD, Flores HE, editors. Biochemistry and Physiology of Polyamines in Plants. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 213–228. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu K, Fu H, Bei Q, Luan S. Inward potassium channel in guard cells as a target for polyamine regulation of stomatal movements. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1315–1326. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.3.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouchereau A, Aziz A, Larher F, Martin-Tanguy J. Polyamines and environmental challenges: recent development. Plant Sci. 1999;140:103–125. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alcázar R, Marco F, Cuevas °C, Patrón M, Ferrando A, Carrasco P, et al. Involvement of polyamines in plant response to abiotic stress. Biotechnol Lett. 2006;28:1867–1876. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-9179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groppa MD, Benavides MP. Polyamines and abiotic stress: recent advances. Amino Acids. 2008;34:35–45. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torrigiani P, Rabiti AL, Bortolotti C, Betti L, Marani F, Canova A, et al. Polyamine synthesis and accumulation in the hypersensitive response to TMV in Nicotiana tabacum. New Phytologist. 1997;145:467–473. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mo H, Pua EC. Upregulation of arginine decarboxylase gene expression and accumulation of polyamines in mustard (Brassica juncea) in response to stress. Physiol Plant. 2002;114:439–449. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1140314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez-Amador MA, Leon J, Green PJ, Carbonell J. Induction of the arginine decarboxilase ADC2 gene provides evidence for the involvement of polyamines in the wound response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:1454–1463. doi: 10.1104/pp.009951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Urano K, Yoshiba Y, Nanjo T, Igarashi Y, Seki M, Sekiguchi F, et al. Characterization of Arabidopsis genes involved in biosynthesis of polyamines in abiotic stress responses and developmental stages. Plant Cell Environ. 2003;26:1917–1926. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanfrey C, Sommer S, Mayer MJ, Burtin D, Michael AJ. Arabidopsis polyamine biosynthesis: absence of ornithine decarboxylase and the mechanism of arginine decarboxylase activity. Plant J. 2001;27:551–560. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hummel I, Bourdais G, Gouesbet G, Couee I, Malmberg RL, El Amrani A. Differential gene expression of arginine decarboxylase ADC1 and ADC2 in Arabidopsis thaliana: characterisation of transcriptional regulation during seed germination and seedling development. New Phytol. 2004;163:519–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soyka S, Heyer AG. Arabidopsis knockout mutation of ADC2 gene reveals inducibility by osmotic stress. FEBS Lett. 1999;458:219–223. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alcázar R, Cuevas °C, Patron M, Altabella T, Tiburcio AF. Abscisic acid modulates polyamine metabolism under water stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol Plant. 2006;128:448–455. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuevas JC, López-Cobollo R, Alcázar R, Zarza X, Koncz C, Altabella T, et al. Putrescine as a signal to modulate the indispensable ABA increase under cold stress. Plant Signal Behav. 2009;4:219–220. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.3.7861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cuevas JC, López-Cobollo R, Alcázar R, Zarza X, Koncz C, Altabella T, et al. Putrescine is involved in Arabidopsis freezing tolerance and cold acclimation by regulating abscisic acid levels in response to low temperature. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1094–1105. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.122945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattoo AK, Minocha SC, Minocha R, Handa AK. Polyamines and cellular metabolism in plants: transgenic approaches reveal different responses to diamine putrescine versus higher polyamines spermidine and spermine. Amino Acids. 2010;38:405–413. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar A, Altabella T, Taylor MR, Tiburcio AF. Recent advances in polyamine research. Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2:124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galston AW, Kaur-Sawhney R, Altabella T, Tiburcio AF. Plant polyamines in reproductive activity and response to abiotic stress. Botanical Acta. 1997;110:197–207. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy M, Wu R. Arginine decarboxylase transgene expression and analysis of environmental stress tolerance in transgenic rice. Plant Sci. 2001;160:869–875. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9452(01)00337-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishitani M, Xiong L, Stevenson B, Zhu JK. Genetic analysis of osmotic and cold stress signal transduction in Arabidopsis: Interactions and convergence of abscisic acid-dependent and abscisic acid-independent pathways. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1935–1949. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.11.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alcázar R, García-Martínez JL, Cuevas °C, Tiburcio AF, Altabella T. Overexpression of ADC2 in Arabidopsis induces dwarfism and late-flowering through GA deficiency. Plant J. 2005;43:425–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinet M, Ndayiragije A, Lefèvre I, Lambillotte B, Dupont-Gillain CC, Lutts S. Putrescine differently influences the effect of salt stress on polyamine metabolism and ethylene synthesis in rice cultivars differing in salt resistance. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:2719–2733. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verslues PE, Agarwai M, Katiyar-Ayarwai S, Zhu J, Zhu JK. Methods and concepts in quantifying resistance to drought, salt and freezing, abiotic stresses that affect plant water status. Plant J. 2006;45:523–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahajan S, Tuteja N. Cold, salinity and drought stresses: an overview. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;444:139–158. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galiba G, Vágújfalvi A, Li C, Soltész A, Dubcovsky J. Regulatory genes involved in the determination of frost tolerance in temperate cereals. Plant Sci. 2009;2009:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lang V, Mäntylä E, Welin B, Sundberg B, Tapio Palva E. Alterations in water status, endogenous abscisic acid content and expression of rab 18 gene during the development of freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:1341–1349. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.4.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomashow MF. So what's new in the field of plant cold acclimation? Lots! Plant Physiol. 2001;125:89–93. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alcázar R, Planas J, Saxena T, Zarza X, Bortolotti C, Cuevas JC, et al. Putrescine accumulation confers drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing the homologous Arginine decarboxylase 2 gene. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48:547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang J, Zhang J, Liu K, Wang Z, Liu L. Involvement of polyamines in the drought resistance of rice. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:1545–1555. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi J, Fu XZ, Peng T, Huang XS, Fan QJ, Liu JH. Spermine pretreatment confers dehydration tolerance of citrus in vitro plants via modulation of antioxidative capacity and stomatal response. Tree Physiol. 2010;30:914–922. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpq030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valdés-Santiago L, Guzmán-de-Peña D, Ruiz-Herrera J. Life without putrescine: disruption of the eneencoding polyamine oxidase in Ustilago maydis odc mutants. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010;10:928–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urano K, Yoshiba Y, Nanjo T, Ito T, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Arabidopsis stress-inducible gene for arginine decarboxylase AtADC2 is required for accumulation of putrescine in salt tolerance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313:369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Capell T, Bassie L, Christou P. Modulation of the polyamine biosynthetic pathway in transgenic rice confers tolerance to drought stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9909–9914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306974101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamaguchi K, Takahashi Y, Berberich T, Imai A, Takahashi T, Michael AJ, et al. A protective role for the polyamine spermine against drought stress in Arabidopsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:486–490. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taiz L, Zeiger E. Plant physiology. USA: Sinauer Associates Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson AJ, Jackson AC, Symonds RC, Mulholland BJ, Dadswell AR, Blake PS, et al. Ectopic expression of a tomato 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene causes over-production of abscisic acid. Plant J. 2000;23:363–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor IB, Burbidage A, Thompson AJ. Control of abscisic acid synthesis. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:1563–1574. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.350.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang SY. Changes in polyamines and ethylene in cucumber seedlings in response to chilling stress. Physiol Plant. 1987;69:253–257. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kramer GF, Wang CY. Effects of chilling and temperature preconditioning on the activity of polyamine biosynthetic enzymes in zucchini squash. J Plant Physiol. 1990;136:115–119. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee TM, Lur HS, Chu C. Role of abscisic acid in chilling tolerance of rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings. II. Modulation of free polyamine levels. Plant Sci. 1997;126:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen W, Nada K, Tachibana S. Involvement of polyamines in the chilling tolerance of cucumber cultivars. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:431–439. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.1.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He L, Nada K, Kasukabe Y, Tachibana S. Enhanced susceptibility of photosynthesis to low-temperature photoinhibition due to interruption of chill-induced increase of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxilase activity in leaves of spinach (Spinacia olaracea L.) Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:196–206. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiesa MA, Ruiz OA, Sanchez DH. Lotus hairy roots expressing inducible arginine decarboxylase activity. Biotechnol Lett. 2004;26:729–733. doi: 10.1023/b:bile.0000024097.59742.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koide RT, Robichaux RH, Morse SR, Smith CM. Plant water status, hydraulic resistance and capacitance. In: Pearcy RW, Ehleringer JR, Mooney HA, Rundel PW, editors. Plant Physiological Ecology: field methods and instrumentation. Londres: Chapman & Hall; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Birecka H. Assay methods for enzymes of polyamine metabolism. In: Slocum RD, Flores HE, editors. Biochemistry and physiology of polyamines in plants Boca Raton. CRS Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maiale S, Sanchez DH, Guirado A, Vidal A, Ruiz OA. Spermine accumulation under salt stress. J Plant Physiol. 2004;161:35–42. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-01167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peirson NS, Butler JN, Foster RG. Experimental validation of novel and conventional approaches to quantitative real-time PCR data analysis. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]