Abstract

Objective

Previous findings suggest a relation between trauma exposure and risk for schizotypal personality disorder (SPD). However, the reasons for this relationship are not well understood. Some research suggests that exposure to trauma, particularly early trauma and child abuse, as well as PTSD may play a role.

Methods

We examined subjects (N=541) recruited from the primary care clinics of an urban public hospital as part of an NIMH-funded study of trauma related risk and resilience. We evaluated childhood abuse with the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) and the Early Trauma Inventory (ETI) and SPD with the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (SNAP). We assessed for lifetime PTSD using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS).

Results

We found that of the three forms of abuse analyzed (emotional, physical, and sexual), only emotional abuse significantly predicted SPD (p<.001, R=0.28) when all three abuse types were simultaneously entered into a regression model. Lifetime PTSD symptoms also significantly predicted SPD (p<.001, R=0.26). PTSD was specifically predictive of four of the eight SPD symptoms (p≤.001): excessive social anxiety, a lack of close friends or confidants, unusual perceptual experiences, and eccentric behavior or appearance. Using a Sobel test, we also found a partial mediation effect of PTSD on the relation between emotional abuse and SPD (z=3.45, p<.001).

Conclusions

These findings point to the important influence of emotional abuse on SPD and suggest that PTSD symptoms may provide a link between damaging childhood experiences and SPD symptoms in traumatized adults.

Keywords: Child Abuse, Childhood Maltreatment, PTSD, Schizotypal Personality Disorder, Trauma

The Differential Effects of Child Abuse and PTSD on Schizotypal Personality Disorder

Studies have shown that childhood (emotional, physical, and sexual) abuse is associated with many long-term psychological effects, including substance abuse, depression, suicidality, and personality disorders (PDs) [1, 2]. However, the specific mechanisms accounting for the relationship between childhood abuse and these negative mental health outcomes are not fully understood. Evidence suggests that posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be one pathway linking childhood abuse and later psychopathology. Early childhood trauma increases risk for additional trauma exposure as an adult and also increases one's likelihood of developing PTSD as a result of a subsequent trauma [3, 4]. Researchers have also found a dose-response relationship between lifetime level of trauma exposure and risk for the development of PTSD [4-6]. One explanation that has been offered to account for the relationship between childhood abuse and the wide range of associated mental health problems is that this risk is partially accounted for by PTSD among adults with a history of childhood abuse. Some studies suggest that PTSD symptoms mediate the relationship between early childhood trauma exposure and risk for adult psychopathology [7, 8]. For example, some recent research suggests that the relationship between childhood abuse and risk for substance use as an adult is accounted for by attempts to “self medicate” PTSD symptoms using drugs and alcohol [9].

Recently, there has been a particular focus on understanding how childhood abuse may increase the risk of developing PDs in adulthood. A community-based study by Johnson et al. [10, 11] showed that individuals who experienced childhood abuse or neglect were more than four times as likely to develop a PD in early adulthood. The investigators also found that verbal (i.e., emotional) abuse predicted PD symptoms in adolescence and adulthood, even after controlling for other forms of child abuse and cooccurring psychiatric disorders [10]. Specifically, this study found that emotional abuse was associated with increased risk of elevated borderline, narcissistic, paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal PD symptom levels in adolescence and early adulthood. Ruggiero, Bernstein, and Handelsman [12] also found a link between child abuse and risk for PDs in their sample of male VA patients. Their results demonstrated that different patterns of childhood abuse and neglect related to different PDs, suggesting more than a general association between childhood maltreatment and PDs. These studies investigated the overall relationship between childhood abuse and later development of any of the ten PDs outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders [DSM-IV; 13]. They did not focus on the relationship between abuse and risk for any specific PD. Therefore these studies do not clarify to what degree childhood abuse may be associated with characteristics of any one PD (e.g., self harm as a symptom of borderline PD or unusual perceptual experiences as a symptom of schizotypal PD) as opposed to increased risk for factors that are common across PDs (e.g., interpersonal difficulties).

Some research has focused particularly on the association between schizotypal PD (SPD) and child abuse. An increasing body of research indicating an association between history of childhood trauma and increased risk for adult psychotic symptoms [5, 14, 15] has led researchers to investigate the specific association between the development of SPD symptoms and childhood abuse. SPD is one of the most controversial of the ten DSM-IV PDs, with some research suggesting that SPD should not exist as a distinct disorder [16, 17] and some discussion of removing SPD as a diagnostic category in DSM-5. Instead, researchers have suggested that the eccentric symptoms that seem to set SPD apart may be better understood as a trait modifier for other PDs [18]. There is also evidence that SPD's unique symptoms could be represented through a specific pathological personality trait (i.e., peculiarity) [19]. Research has consistently shown that high rates of comorbidity exist among the ten PDs, especially within the same DSM-IV PD clusters [20]. With existing research suggesting that change to the current diagnostic setup of PDs is necessary, understanding how the specific symptoms of schizotypy may be influenced by traumatic life events is particularly relevant.

Accumulating evidence supports the hypothesis that early trauma exposure increases the risk of developing peculiar perceptions and beliefs [21]. Berenbaum et al. [22] found that childhood maltreatment was associated with elevated levels of cognitive-perception SPD symptoms (e.g., ideas of reference, magical thinking, unusual perceptual experiences, and paranoid ideation) and with SPD in general. Consistent with previous findings [10], a follow-up study by Berenbaum et al. [21] showed emotional abuse related to SPD most strongly, even when controlling for other forms of maltreatment. Additionally, the investigators found that PTSD acted as a partial mediator of the association between childhood maltreatment and SPD [22], suggesting that PTSD may represent one pathway in which child abuse translates into SPD. These researchers posit that developing peculiar beliefs or perceptions may provide a way of coping with trauma, like childhood abuse. However, they indicate that additional research on the role of PTSD is needed.

The similar (and sometimes overlapping) nature of PTSD and psychosis and their co-occurrence in trauma survivors need to be taken in to account in understanding any potential relation between child abuse, PTSD, and psychotic-spectrum disorders, including SPD. Recent reviews on the relationship of psychotic symptoms and PTSD-associated symptoms suggest the links between symptoms of PTSD (e.g., re-experiencing, flashbacks, dissociation) and psychotic symptoms are multi-determinant [5, 23]. Some argue that the association between psychosis and high rates of trauma exposure understandably leads to high comorbidity with PTSD, and that PTSD may act as an indicator of more severe mental illness in such cases [8]. Dissociative experiences often characteristic of PTSD can also increase one's vulnerability to psychotic-like symptoms later in life [5]. Another possibility is that they represent similar entities, and therefore operate on a continuum of reactions to extreme stress. However, research indicates that comorbid PTSD and secondary psychosis are not associated with a family history of psychotic disorder, suggesting that PTSD and psychosis may not share common underlying genes [24]. These reviews further suggest that it is likely that different processes vary across individual cases.

Only limited research has explored the complex relationship between several types of childhood abuse, lifetime PTSD symptoms, and SPD. If PTSD symptoms, regardless of whether they are a direct result of child abuse, are a mechanism linking child abuse and SPD, this suggests the important role that both early abuse and PTSD symptomology may play in exacerbating schizotypy. Thus, the goal of this paper is to examine the potential relationship among these variables in a highly-traumatized population. Specifically, the current study will explore: (1) how each form of childhood abuse influences the development SPD, (2) if the presence of lifetime PTSD symptoms has a mediating effect on the association between SPD and childhood abuse, and (3) if certain symptoms of SPD are relevant to these relationships.

Method

Procedure

Data for this study were collected as part of the Grady Trauma Project, a 5-year NIH-funded study of risk and resilience to PTSD at Grady Memorial Hospital [see 25, 26 for a more detailed description of study methods]. We recruited participants from the General Medical and Obstetric/Gynecological Clinics at a publicly funded, not-for-profit healthcare system in Atlanta, Georgia. Research participants were recruited while either waiting for their medical appointments or while waiting with others who were scheduled for medical appointments. Individuals were excluded if they were under the age of 18, actively psychotic, or unwilling or unable to give consent. Because the study employed multiple research assistants, potential participants were also asked to confirm that they had not previously participated in the study and were excluded if they had. In addition, participants were not allowed to “self refer” to the study based on having learned about it through friends or family members. Though it could not be confirmed that family members of participants had not themselves participated, the nature of recruitment and the size of the patient population from which participants were recruited significantly decreased the possibility that this occurred.

Subjects responded to a battery of self-report measures which took 45 to 75 minutes to complete (dependent in large part on the extent of the participant's trauma history and symptoms). All measures were obtained by verbal interview. Study participants who completed the initial interview were invited to participate in three more phases of the study, each occurring on a separate day, during which a more comprehensive, structured-interview-based assessment of trauma history, PTSD, other Axis I symptoms, and associated aspects of psychological functioning, including personality, was obtained. Written and verbal informed consent was obtained for all participants during each phase of the study. All procedures in this study were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Emory University School of Medicine and Grady Memorial Hospital.

Measures

Assessment of Childhood Physical, Sexual and Emotional Abuse

Data on history of childhood physical, sexual and emotional abuse were collected using two instruments: a self-report instrument, The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) and a structured trauma interview, the Early Trauma Interview (ETI). The CTQ [27, 28] is a 25-item, brief, reliable and valid assessment instrument assessing sexual, physical, and emotional abuse in childhood [29]. The CTQ was assessed during the initial interview. The ETI is a structured interview with high test-re-test reliability, internal consistency and external validity [30] that assesses childhood physical, sexual and emotional abuse. The ETI was administered during each participant's third interview by a trained interviewer. Researchers created a continuous variable for each abuse type by summing participant item scores. Higher scores on either measure indicated higher levels of reported abuse.

Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (SNAP) [31]

The SNAP is a factor-analytically derived self-report questionnaire with 375 true-false items. Scores can be obtained on 34 Scales: 12 Trait Scales, 3 Temperament Scales, 6 validity Scales, and 13 Personality Disorder Scales. The Personality Disorder Diagnostic Scales map onto the symptoms of the ten DSM-IV PDs [32]. Although the DSM diagnostic criteria can be applied to SNAP items, it is generally used as a continuous measure of traits/symptoms. Accordingly, we used continuous measures of SPD and its specific symptoms for this study. Reliability and validity has been studied extensively and proven adequate for the majority of the scales [33-35].

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) [36, 37]

The CAPS is an interviewer-administered diagnostic instrument measuring PTSD, and includes items that rate social and occupational functioning, global PTSD symptom severity, and the validity of participant's responses. The CAPS assesses lifetime and current PTSD and yields a continuous measure of the severity of overall PTSD and of the three symptom clusters (intrusion, avoidance, and arousal). The frequency and intensity scores for each of the 17 diagnostic criteria are summed to arrive at a total severity score. This measure has excellent psychometric properties [37, 38].

Interviewers queried participants regarding the worst trauma they experienced inclusive of traumatic events occurring in both childhood/adolescence and adulthood. The CAPS was only administered on traumas that met criterion A of the DSM-IV. The majority of participants in the study (≈75%) reported experiencing multiple types of traumatic events. Traumas reported by participants spanned a range of events, including severe childhood abuse, molestation, rape, violent assaults, and witnessing deaths. For the following analyses, we used a continuous measure of lifetime PTSD symptom severity.

Data Analysis

The overall analytic approach was to examine the predictive utility of the three forms of childhood abuse and PTSD on SPD using SPSS software. Descriptive statistics were computed and bivariate correlations among variables were described. Separate regression models were used to examine the extent to which child abuse predicts SPD and its symptoms when different measures of abuse were used. Linear regression was also used to determine whether PTSD predicts SPD and its specific symptoms. Hierarchical linear regressions were utilized to examine the unique predictive value of PTSD and childhood abuse in estimating SPD. Additionally, we ran a Sobel test to formally assess whether mediation effects were present.

Results

Demographics

The sample consisted of 541 individuals, with 59% females. The subjects were all adult (>18 years; median age of 41) and primarily African American (91.4%). The remainder of the racial composition was as follows: White (5.6%), mixed/other (2.4%), and Hispanic or Latino (0.6%). The sample was predominately poor, with 74.5% of individuals unemployed and 69% coming from households with a monthly income of less than $1,000. The majority of participants were medical patients (>80%). Many participants were also on disability as a result of physical or mental health problems at the time of assessment (17%). Almost 90% of participants reported a trauma that met criterion A for PTSD. The majority of participants reported adult traumas (40.2%) or childhood traumas (29.8%), while 30% of the participants met criteria for both a childhood and adult trauma. More than 74% of participants experienced at least two traumas in their lifetime. Although this was a community sample, the rates of psychopathology in the sample are quite high when compared to prevalence rates of psychopathology found in national representative samples [39, 40] (see table 1). The rates of trauma exposure and psychopathology are not inconsistent with research conducted in studies of similar community samples, however [e.g., 41, 42]. In addition, the continuous SPD variable correlated highly with other SNAP PD scales, with correlations ranging from .15 - .49 (mean r=.28). The highest correlation was between SPD and paranoid PD. This is consistent with other research finding significant correlation between PDs [16, 43], particularly in traumatized samples [44].

Table 1.

Rates of Psychopathology

| Axis I disorders | |

|---|---|

| Major Depression | 35.5 |

| Bipolar Disorder (I and II) | 6.9 |

| Psychotic Disorder | 10.6 |

| Anxiety Disorders (excluding PTSD) | 29.0 |

| PTSD | |

| Current | 16.5 |

| Lifetime | 24.6 |

| Previous psychiatric hospitalization | |

| 16.6 | |

| Previous suicide attempt | |

| 16.3 |

Note: All Axis I disorder diagnoses are obtained from the SCID, except PTSD which was diagnosed using the CAPS. Anxiety disorders include Panic disorder, Agoraphobia, Social Phobia, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, and Anxiety Disorder NOS.

Correlation Analyses of Abuse and PTSD with SPD

We first examined the relationship between sexual, physical, and emotional abuse, PTSD lifetime symptom severity and SPD scores using bivariate correlation analyses. Childhood physical and emotional abuse significantly correlated (p<.01) with SPD using both measures of childhood trauma. Childhood sexual abuse significantly correlated (p<.05) with SPD using the CTQ but not using the ETI. Lifetime PTSD symptom severity also correlated with SPD (p<.01). We also examined how each SPD symptom related to childhood abuse and PTSD. All SPD symptoms correlated with emotional abuse (p<.05) in both abuse measures with the exception of odd beliefs and suspiciousness. Five of the eight SPD symptoms correlated with lifetime PTSD and childhood abuse (physical and emotional; p<.05): excessive social anxiety, a lack of close friends or confidants, unusual perceptual experiences, constricted affect, and eccentric behavior or appearance. Table 2 presents the results of the correlation analyses.

Table 2.

Correlation Analyses between SPD (SNAP), Child Abuse (CTQ; ETI), and Lifetime PTSD symptom severity (CAPS)

| Correlation Analyses |

Physical Abuse |

Sexual Abuse |

Emotional Abuse |

Physical Abuse |

Sexual Abuse |

Emotional Abuse |

PTSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

(CTQ) |

(CTQ) |

(CTQ) |

(ETI) |

(ETI) |

(ETI) |

|

| SPD | .15 | .10 | .27 | .13 | .06 | .23 | .26 |

|

Pearson Correlation

Significance (two-tail) |

<.001** |

.02* |

<.001** |

<.001** |

.21 |

<.001** |

<.001** |

| Ideas of Reference | .07 | .07 | .19 | .09 | .07 | .15 | .08 |

|

Pearson Correlation

Significance (two-tail) |

.13 |

.13 |

<.001** |

.07 |

.14 |

.003** |

.13 |

| Odd Beliefs | .04 | .043 | .10 | -.03 | .01 | .04 | .01 |

|

Pearson Correlation

Significance (two-tail) |

.39 |

.32 |

.02* |

.53 |

.83 |

.43 |

.87 |

| Unusual Perceptions | .11 | .08 | .15 | .10 | .07 | .17 | .25 |

|

Pearson Correlation

Significance (two-tail) |

.01** |

.07 |

.001** |

.05* |

.17 |

<.001** |

<.001** |

| Eccentric Behavior | .15 | .11 | .27 | .17 | .07 | .23 | .22 |

|

Pearson Correlation

Significance (two-tail) |

<.001** |

.01** |

<.001** |

<.001** |

.16 |

<.001** |

<.001** |

| Constricted Affect | .06 | .04 | .17 | .14 | -.02 | .10 | .13 |

|

Pearson Correlation

Significance (two-tail) |

.21 |

.40 |

<.001** |

.005** |

.71 |

.04* |

.02* |

| Social Anxiety | .12 | .04 | .16 | .12 | .05 | .17 | .17 |

|

Pearson Correlation

Significance (two-tail) |

.001** |

.34 |

<.001** |

.015* |

.37 |

.001** |

.001** |

| Lack of Close Friends | .10 | .06 | .21 | .08 | .01 | .16 | .19 |

|

Pearson Correlation

Significance (two-tail) |

.02* |

.19 |

<.001** |

.11 |

.83 |

.001** |

.001** |

| Suspiciousness | .08 | .05 | .12 | -.02 | .001 | .07 | .08 |

|

Pearson Correlation

Significance (two-tail) |

.07 | .26 | .005** | .74 | .98 | .18 | .12 |

For this and all subsequent tables

represents significance at the p<.05 level

p<.01.

Regression Analyses of SPD with Abuse and PTSD

To assess whether childhood abuse predicted SPD, we performed two linear regressions. As shown in Table 3, childhood abuse predicted SPD. In examining measures of childhood abuse from both the CTQ and ETI, only emotional abuse predicted SPD. We next tested whether emotional abuse predicted specific SPD symptoms. Emotional abuse predicted five of the eight SPD symptoms when looking at both measures of abuse (p≤.01): ideas of reference, excessive social anxiety, a lack of close friends or confidants, unusual perceptual experiences, and eccentric behavior or appearance. We found that emotional abuse had the most significant (R2 change=.08 and .05 for the CTQ and ETI respectively) predictive effect on the symptom of eccentric behavior or appearance. No significant gender differences were found.

Table 3.

Linear Regression Predicting SPD from Two Measures of Child Abuse (CTQ; ETI)

| Predicting SPD | Stand.β | T | P | R | R2 change | F change | P change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1a: Child Abuse (CTQ) | .28 | .08 | 15.00 | <.001** | |||

| Step 1b: Child Abuse (ETI) | .24 | .06 | 8.14 | <.001** | |||

| 1a - Physical Abuse | -.06 | -.99 | .32 | ||||

| 1a- Sexual Abuse | -.06 | -1.24 | .22 | ||||

| 1a - Emotional Abuse | .34 | 5.61 | <.001** | ||||

| 1b - Physical Abuse | -.01 | -.07 | .94 | ||||

| 1b – Sexual Abuse | -.05 | -.85 | .40 | ||||

| 1b - Emotional Abuse | .26 | 4.09 | <.001** |

Note: Only 415 subjects were used in the ETI regression analysis due to missing data

Next, using linear regression we examined whether PTSD symptoms predicted SPD and its symptoms. We found that PTSD significantly predicted SPD (p<.001). PTSD was also significantly predictive of four SPD symptoms (p≤.001): excessive social anxiety, a lack of close friends or confidants, unusual perceptual experiences, and eccentric behavior or appearance. Lifetime PTSD had the most significant (R2 change=.04) predictive effect on the symptom of unusual perceptions. Results are shown in Table 4. No significant gender differences were found.

Table 4.

Linear Regression Predicting SPD symptoms from PTSD

| Lifetime PTSD predicting: | R | R2 change | F change | P change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPD (all symptoms) | .26 | .07 | 21.92 | <.001** |

| Unusual Perceptions | .25 | .06 | 20.77 | <.001** |

| Social Anxiety | .24 | .06 | 18.65 | <.001** |

| Eccentricities | .20 | .04 | 12.88 | <.001** |

| Lack of Friends | .19 | .04 | 11.50 | .001** |

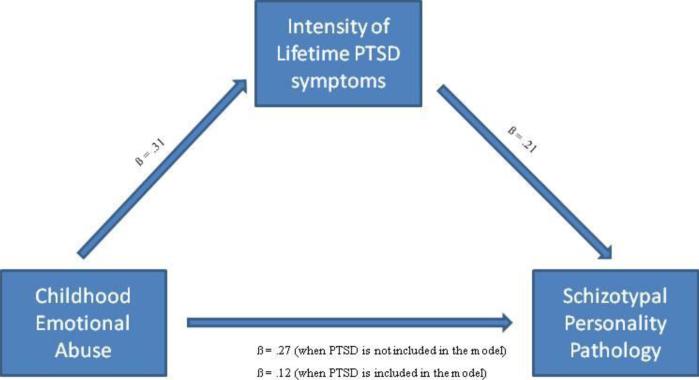

Finally, we formally tested whether or not the association between PTSD and emotional abuse and SPD could be accounted for by mediation. Following recommended guidelines [45], we first verified that there was a significant relation between childhood emotional abuse and both adult SPD and lifetime PTSD symptoms. We confirmed that childhood emotional abuse, based on the CTQ, significantly predicted adult SPD as well as the intensity of lifetime PTSD symptoms (ß= .27, p < .001; ß= .31, p < .001, respectively). We next specified a model to determine whether the significant relation between childhood emotional abuse and adult SPD diminished when PTSD symptoms were proposed as a mediator. We found that this relation between abuse and SPD, while still significant, diminished when lifetime PTSD symptomatology was entered in the first step of a regression model (ß= .12, p < .05), suggesting a partial mediation. To formally determine whether this mediation effect was significant, we conducted a Sobel test [46]. Results from the Sobel test indicated that the mediation effect of PTSD symptoms was significant (z = 3.45, p < .001). These results are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sobel mediation model demonstrating the partial mediation effect of PTSD on the relation between childhood emotional abuse and SPD.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the relationship between the three domains of childhood abuse (i.e., physical, sexual, and emotional), PTSD, and all individual symptoms of SPD. Results from the present study are consistent with previous findings [10, 22] that PDs, and SPD specifically, are associated with childhood abuse. Interestingly, we found that only emotional abuse emerged as a unique predictor of SPD when all abuse types were examined together. This result reiterates the importance of examining all forms of childhood abuse when trying to understand the relationship between childhood maltreatment and later psychopathology. Although emotional abuse has often been ignored in research on the effects of childhood maltreatment, its unique relationship to adult psychopathology and risk for PDs is becoming increasingly clear.

We also found a partial mediating effect of the presence of lifetime PTSD symptoms on the relation between childhood emotional abuse and SPD. This is consistent with prior findings [21] that also demonstrated a partial mediating effect of PTSD. Our results suggest the influence that childhood abuse, and trauma more generally, has on the development of SPD may depend on whether or not an individual develops PTSD in their lifetime. The type or strength of the abuse may determine whether or not there are lasting effects of the abuse, including additional trauma in adulthood, which then may influence whether PTSD emerges. This possibility is supported by previous research showing that child abuse is a risk factor for PTSD and adult psychopathology, and that child abuse and PTSD both affect the risk of developing psychopathology in adulthood regardless of whether or not the PTSD resulted directly from the childhood trauma [3]. Some researchers suggest that PTSD may cause a fundamental change in individuals that may affect personality and influence the development of personality pathology [44]. Specifically, Herman's [47] model suggests that “complex trauma”, conceptualized as severe and repeated exposure to abuse often beginning in childhood, leads to changes in the personality system. This may be particularly important for the present study, in which a majority of participants could be conceptualized as having complex trauma based on their abuse histories. Longitudinal research that focuses on the pathway between different forms of abuse, the development of PTSD, and later traumatization may provide a clearer picture of how early trauma can lead to changes in personality pathology broadly, and to schizotypy in particular.

Because SPD is often viewed as a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder and is linked to peculiar and eccentric behaviors or beliefs, we explored which SPD symptoms related to child abuse and PTSD. Previously, Berenbaum and colleagues [22] found important links between cognitive-perception SPD symptoms, child abuse, and PTSD. Our results suggest that having unusual perceptual experiences and eccentric behaviors may be the most strongly related symptom linking child abuse and PTSD. The presence of excessive social anxiety and the absence of close confidants also appear to play a role in why childhood abuse is associated with increased risk for developing SPD. The cognitive effects of PTSD (e.g., negative appraisal or constant perceived threat) [5] could relate to the magical thinking found in SPD as interpretations of intrusive thoughts or flashbacks that occurred with PTSD. Additionally, research on resiliency in the face of trauma and PTSD has shown that social support can act as a buffer against the detrimental effects of trauma [48], and the isolation that often accompanies SPD may prohibit adequate coping or one's ability to test reality appropriately [8]. Future research should continue to explore the link to specific SPD symptoms and examine how this may be important to other schizophrenia-spectrum disorders as well.

Limitations

The primary limitation for this study was the use of cross-sectional and retrospective data. We cannot determine causality among our variables, and longitudinal research which examines the etiology of SPD as it relates to trauma is still needed. Despite the potential problems of retrospective reporting, it is nonetheless helpful in the absence of other options as we try and sort out the long term effects of trauma.

Another limitation in this study was the high level of comorbidity across SNAP PD symptom scales. Previous research has shown that individuals with personality pathology often have high rates of symptomatology across various PDs, as opposed to confined symptoms of one disorder [43]. This problem of comorbidity is one reason that researchers have called for change in the DSM-IV PD diagnostic system. In particular, research has focused on underlying factors (e.g., internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and emotional dysregulation) that may account for this cross diagnostic overlap [49, 50]. The purpose of this study was not to try and discover how pure SPD symptoms (in the absence of other symptomotology) relate to trauma, because we are aware that a pure disorder rarely exists. Instead, we hoped to clarify how symptoms characteristic of SPD in highly traumatized individuals may be important in our understanding of trauma and its repercussions. The data we present here, although specific to the current SPD diagnosis, is still useful to understanding the relationship between trauma, PTSD, and personality even given the limitations of the current diagnostic system.

Additionally, we had a fairly homogeneous sample, with respect to both race and income. Although the sample enabled us to examine the link between child abuse and adult SPD in a highly traumatized community sample, generalizeability of our findings should be taken with caution. We believe, however, that this limitation is balanced by two factors. First, this population tends to be under-represented in research on personality disorders. Secondly, the high level of trauma and PTSD in the sample increases the public health relevance of our results.

Finally, based on study exclusion criteria, we were not able to test the association between SPD and schizophrenia in this sample. This relationship remains an important area of future research in understanding how both may be associated with PTSD and trauma. Some researchers argue that PTSD and psychosis are similar entities on a spectrum of ways that people react to extreme stress [5], and the similarities between certain symptoms of PTSD and psychotic-like symptoms makes it difficult for us to fully identify how PTSD and SPD can be understood together. Research on this topic is far from conclusive, however, and continuing to explore the complex relationship among all of these disorders is necessary.

Clinical Implications

These findings elucidate the importance of considering childhood abuse as a potential etiological factor in the development of SPD. In particular, knowing that emotional abuse and the presence of PTSD symptoms increases the risk of developing SPD could have important implications for the conceptualization and treatment of SPD (similarly to how these factors have affected our understanding of borderline PD). Currently, controversy exists over whether SPD is a discrete disorder, a variant of the other Cluster A PDs, or a clinical syndrome that relates more closely to schizophrenia [17, 51]. How the occurrence of childhood abuse and PTSD uniquely affect symptoms of SPD may help us better understand SPD and where it fits as a pathological entity. For example, it is possible that the pathway to SPD is heterogeneous, with a genetic liability to schizophrenia representing one mechanism that symptom development occurs and an environmentally influenced (through extreme stress related to trauma and PTSD exposure) condition representing another mechanism. Determining an environmentally mediated pathway to SPD symptoms could potentially help clinicians conceptualize treatment plans related to SPD. In particular, treatment for PTSD symptoms, like exposure-based cognitive behavioral therapies, which have shown efficacy in symptom reduction [52, 53] may provide a first step in treating SPD.

In addition, the distinctive role of emotional abuse in risk for adult psychopathology is again demonstrated in this study. Treatments and interventions for childhood maltreatment should focus on the particularly detrimental effects that result from emotional abuse. It may be that these distinct effects of emotional abuse reflect the severity or all-encompassing nature of the abuse. Another possibility is that the presence of emotional abuse is an indicator of low levels of social support in the child's life, a known risk factor for the development of later psychopathology. Future studies that aim to establish the relationship between childhood abuse and negative health outcomes should explore the separate effects that each form of abuse may have on outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was primarily supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH071537). Support also included Emory and Grady Memorial Hospital General Clinical Research Center, NIH National Centers for Research Resources (M01 RR00039), and the Burroughs Welcome Fund. We thank Allen Graham, BA, Eboni Johnson, BS, Josh Castleberry, BS, Daniel Crain, BS, Nineequa Blanding, BS, Daphne Pierre, BS, and Rachel Hershenberg, BA for their assistance with data collection and support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kendler K, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57::953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacMillan H, et al. Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1878–1883. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breslau N, et al. Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: Results from the Detroit Area Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:902–907. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schumm J, Briggs-Phillips M, Hobfall S. Cumulative interpersonal traumas and social support as risk and resiliency factors in predicting PTSD and depression among inner-city women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:825–836. doi: 10.1002/jts.20159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrison A, Frame L, Larkin W. Relationship between trauma and psychosis: A review and integration. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;42:331–353. doi: 10.1348/014466503322528892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz A, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder among African Americans in an inner city mental health clinic. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:212–216. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazza J, Reynolds W. Exposure to violence in young inner-city adolescents: Relationships with suicidal ideation, depression, and PTSD symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;27:203–213. doi: 10.1023/a:1021900423004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueser K, et al. Trauma, PTSD, and the course of severe mental illness: An interactive model. Schizophrenia Research. 2002;53:123–143. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Najavits L, Weiss R, Shaw S. The link between substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder in women: A research review. The American Journal on Addictions. 1997;6:273–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson J, et al. Childhood verbal abuse and risk for personality disorders in adolescence and early adulthood. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42:16–23. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.19755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson J, et al. Childhood maltreatment increases risk for personality disorders during early adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:600–606. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruggiero J, Bernstein D, Handelsman L. Traumatic stress in childhood and later personality disorders: A retrospective study of male patients with substance abuse. Psychiatric Annals. 1999;29:713–721. [Google Scholar]

- 13.APA . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Author; Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gearon J, et al. Traumatic life events and PTSD among women with substance use disorders and schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:522–528. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Read J, et al. Childhood trauma, psychosis, and schizophrenia: A literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112:330–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Widiger T, Simonsen E. Alternative dimensional models of personality disorder: Finding common ground. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:110–130. doi: 10.1521/pedi.19.2.110.62628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westen D, Shedler J. Revising and assessing Axis II, Part 2: Toward an empirically based and clinically useful classification of personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:273–285. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortigo K, et al. Exploring the classification of Cluster A personality disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry. submitted manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krueger R, Eaton N. Personality traits and the classification of mental disorders: Toward a more complete integration in DSM-V and an empirical model of psychopathology. Psychological Medicine. doi: 10.1037/a0018990. submitted manuscript. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skodol A. Manifestations, clinical diagnosis, and comorbidity. In: Oldham J, Skodol A, Bender D, editors. Textbook of personality disorders. American Psychoanalytic Publishing; Washington D.C.: 2005. pp. 57–87. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berenbaum H, et al. Psychological trauma and schizotypal personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:502–519. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berenbaum H, Valera E, Kerns J. Psychological trauma and schizotypal symptoms. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003;29:143–152. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamner M, et al. Psychotic features and illness severity in combat veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45:846–852. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sautter F, et al. Family history study of posttraumatic stress disorder with secondary psychotic symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1775–1777. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley R, et al. Influence of child abuse on adult depression: Moderation by the corticotrophin-releasing hormone receptor gene. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65(2):190–200. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powers A, Ressler K, Bradley B. The protective role of friendship on the effects of childhood abuse and depression. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26(1):46–53. doi: 10.1002/da.20534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernstein D, et al. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(3):340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernstein D, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernstein D, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(2):169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bremner J, Vermetten E, Mazure C. Development and preliminary psychometric properties of an instrument for the measurement of childhood trauma: The Early Trauma Inventory. Depression and Anxiety. 2000;12:1–12. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1<1::AID-DA1>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark L. SNAP (Schedule for nonadaptive and adaptive personality): Manual for administration, scoring and interpretation. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trull T. Dimensional models of personality disorder: Coverage and cutoffs. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19(3):262–282. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark L, et al. Convergence of two systems for assessing specific traits of personality disorder. Psychological Assessment. 1996;5:81–91. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melley A, Oltmanns T, Turkheimer E. The Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (SNAP): Temporal stability and predictive validity of the diagnostic scales. Assessment. 2002;9(2):181–187. doi: 10.1177/10791102009002009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds S, Clark L. Predicting dimensions of personality disorder from domains and facets of the Five-Factor Model. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:199–222. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blake D, et al. A clinician rating scale for assessing current lifetime PTSD: the CAPS-1. Behavior Therapy. 1990;13:187–188. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blake D, et al. The development of a clinician administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weathers F, Keane T, Davidson J. Clinician-administered PTSD scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:590–596. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kessler R, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Switzer G, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and service utilization among urban mental health center clients. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12:25–39. doi: 10.1023/A:1024738114428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liebschutz J, et al. PTSD in urban primary care: High prevalence and low physician recognition. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:719–726. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0161-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lenzenweger M, et al. DSM-IV personality disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunn N, et al. Personality disorders in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder and depression. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:75–82. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014680.54051.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sobel M. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology. American Sociological Association; Washington, DC: 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herman J. Trauma and recovery. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vranceanu A, Hobfall S, Johnson R. Child multi-type maltreatment and associated depression and PTSD symptoms: The role of social support and stress. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krueger R. Continuity of axes I and II: Toward a unified model of personality, personality disorders, and clinical disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:233–261. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westen D, Shedler J. Personality diagnosis with the Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure (SWAP): Integrating clinical and statistical measurement and prediction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:810–822. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ortigo K, et al. Exploring the classification of Cluster A personality disorders. in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bradley R, et al. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:214–227. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schnurr P, Friedman M, Engel C. Cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in women: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:820–830. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]