Abstract

BACKGROUND

Proper evaluation of the generalizability of an instrument is critical for its use across different social contexts such as caregiver status.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the differential item functioning of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale, patterns of response to each item of the CES-D Scale attributable to caregiver status was assessed.

STUDY DESIGN

Using a cross-study comparison method, a sample of 58 matched pairs of Korean American caregivers and noncaregivers was used for matched moderated regression analysis on the CES-D Scale.

RESULTS

The authors identified three items that vary according to caregiver status in the present study: Item 2 (My appetite was poor), Item 4 (I felt that I was as good as other people), and Item 14 (I felt lonely).

CONCLUSIONS

Beyond assessing the level of depression through total CES-D scores, it is important to examine variations in the items of the CES-D Scale across different social contexts.

Keywords: cross-cultural issues, depression, rating scale and scales

BACKGROUND

Depression and Caregiving Among Korean American Women

With 1.5 million people, Korean Americans (KAs) are the fifth largest Asian group in the United States (Reeves & Bennett, 2004). However, for KAs, very limited data on the prevalence of depression are available, particularly for KA women. The data that have been collected suggest an increased susceptibility among KA immigrant women, about 48.7% of whom reported a high level of depression, which was demonstrated on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale cutoff score of 16 or higher (Kim & Rew, 1994).

KA immigrant women are vulnerable to depression because they need to straddle distinct cultures and adjust to different sociocultural roles and expectations in a new country (Kim, Han, Shin, Kim, & Lee, 2005; Kim & Rew, 1994; Shin, 1993; Um & Dancy, 1999). In Korea, the traditional family is husband-dominant, and the husband is the breadwinner. However, as Korean families adjust to a new culture and society, the traditional family structure and relationships tend to be modified (Um & Dancy, 1999). Currently, in most KA families, wives as well as husbands contribute to the household income, making the majority of KA families more egalitarian in terms of gender roles. More than 99% of KA women have reported that they were working outside the home, and 36% of them had not worked in Korea before coming to the United States (Um & Dancy, 1999). Stress related to the changes in role and work burdens have increased the risk for depression among this population.

Along with contributing to the household income, KA immigrant women are expected to continue their role as a primary caregiver for the family. Traditionally, caring for older parents or sick family members is regarded as one of the main responsibilities of women in Korea. Hence, KA women are living under the influence of a strong sense of filial obligation (Kong, 2007). All of the KA caregivers interviewed for a study on KA caregivers’ experiences reported that taking care of frail family members was a part of their natural responsibilities (Kim & Theis, 2000). Based on a review of 32 studies on the experiences of caregivers, Kong (2007) found that a major motivation for caregiving among KA caregivers was filial obligation, whereas White caregivers were more likely to be motivated by filial affection. She also discussed the increased risk for depression among caregivers in relation to the amount of burdens placed on them. Youn, Knight, Jeong, and Benton (1999) have reported that compared with Whites, KA caregivers experienced higher levels of burden and anxiety than their White counterparts. These findings indicated that the social context of expecting women to take major caregiving roles as well as ethnicity based on a traditional culture play significant roles in determining KA women’s experiences with depression. Social context and ethnicity have been found to contribute to differences in the manifestations of depressive symptoms as well as in the prevalence of depression (Roxburgh & Xu, 2006; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001).

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

More than 40 instruments have been developed and used to measure depression (Kim, 2002). The most commonly used instrument for measuring depression among KA immigrant women is the CES-D Scale (Kim & Rew, 1994; Lee & Farran, 2004; Shin, 1993; Um & Dancy, 1999). The CES-D Scale, a 20-item self-report scale, has been widely used to measure the level of depression in both clinical and community settings (Radloff, 1977; Radloff & Locke, 1986). Responses are scored based on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time; less than 1 day a week) to 3 (most or all of the time; 5–7 days a week). A score of 16 has been used as a cutoff point to dichotomize depressed and nondepressed groups. The scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity across various populations, including Koreans (Black, Markides, & Miller, 1998; Farran, Miller, Kaufman, Donner, & Fogg, 1999; Lee & Farran, 2004; Roberts, 1980). However, lack of consistency regarding item responses in the measurement of depression suggests that response patterns may be affected by unique conceptualizations of depression among different ethnic groups (Perreira, Deeb-Sossa, Harris, & Bollen, 2005). Relying on instruments without much consideration of their applicability across different social contexts and ethnicities may result in inconsistent findings (Perreira et al., 2005). Although the stability and applicability of the CES-D Scale across different ethnic groups have been evaluated, limited numbers of studies have addressed the cross-contextual generalizability of the CES-D Scale.

Differential Item Functioning

One approach to addressing cross-contextual generalizability is by performing differential item functioning (DIF) analysis. DIF consists of an examination of whether each item in an instrument is being interpreted consistently, relative to the rest of the items in the instrument. If the items are being interpreted differently across social contexts, this can be an indicator that the instrument is not measuring the same construct across them. If a large number of items are subject to such biases, it can threaten the reliability and validity of the instrument (Holland & Wainer, 1993).

The most popular methods of estimating DIF are based on item-response theory (IRT). IRT models generate item parameters and then test for group differences in the estimation of each item parameter (Holland & Wainer, 1993). These methods have three major drawbacks. First, they assume a parametric IRT model for the scale. If the assumed model is incorrect, the resulting DIF analysis will be moot. Second, the meaning of group differences can be very difficult to understand both in terms of meaning and in terms of the implications for use of the scale. Finally, these models generally require relatively large samples (e.g., 150 participants per group), limiting their use with populations where large samples are difficult or expensive to obtain. One alternative method of estimating biases with smaller samples is matched moderated regression (MMR) analysis (Young, Fogg, & Choi, 2002). MMR analysis has four distinctive benefits. The first is that the parameters that are estimated from MMR analysis are relatively easy to interpret. The intercept differences reflect mean item differences between groups that are independent of the latent trait. For example, Gelin and Zumbo (2003) have noted intercept differences between men and women on an item about crying when measuring depression. Women have reported crying more than men, independent of their level of depression. On the other hand, slope differences reflect interaction effects in the relationship between the item and the total scale score, which is used to estimate the latent trait. Slope differences demonstrate that the item may be more correlated to the latent trait in one group than it is in another. There are other DIF models that do not require the use of an IRT model (Swaminathan & Rogers, 1990), but they also require large samples to estimate the DIF effects.

A second benefit of MMR analysis is that it has more statistical power than IRT models that are generally used to estimate DIF. MMR employs the use of least squares estimation rather than maximum likelihood types of estimation and so large samples are not required to produce accurate and robust results. The maximum likelihood estimates used in item-response DIF models often requires large sample sizes (e.g., 150 or more participants) to estimate these same biases (Rao & Sinharay, 2006).

The third benefit of MMR analysis is that the calculation of effects is less ambiguous than IRT models. IRT models require specification of a single or multiple parameter measurement model and the specification of constraints on the selected model. Both of these decision points require an experienced psychometrician and can be open to debate as to the best choice. MMR analysis, on the other hand, is a single model for performing DIF. Thus, it avoids the challenges inherent in selecting which measurement model the scientist wants to assume best describes his or her data, and which of the resulting parameters are the optimal ones to constrain when looking for group differences.

Finally, MMR analysis associated with DIF is relatively easy to calculate. Any scientist with access to statistical software that performs multiple regression analysis can analyze his or her data without much difficulty. MMR analysis is based on using linear regression to estimate the relationship between the latent trait of interest and each item of the scale. The procedure also produces more interpretable results because the samples are matched.

Previous Example of the Use of MMR Analysis

Young et al. (2002) used MMR analysis to examine the differences in the manifestations of depressive symptom attributable to ethnicity. Using two groups of female caregivers of patients with dementia—Caucasian American (CA) caregivers and Korean caregivers in Korea (KK)––they assessed group differences in the depressive symptoms that are described in the CES-D Scale. For the study, CA caregivers (N = 100) completed the English version of the CES-D Scale and KK caregivers (N = 78) completed the Korean version of the CES-D Scale, the CES-D-K. Details of sampling and research procedures are reported elsewhere (Lee & Farran, 2004; Young et al., 2002). KK caregivers reported significantly higher levels of depression than CA caregivers. Young et al. (2002) questioned whether ethnic differences in the levels of depression reflected differences in severity of depression or whether the group differences were attributable to factors unrelated to depression. They used a sample of 62 matched pairs for MMR analysis. They found significant ethnic group differences in terms of the intercept on 10 items and the slope on 1 item. The 9 remaining items showed no evidence of ethnic group differences, which made them conclude that these items on the CES-D Scale are generalizable across CA and KK caregivers (Young et al., 2002).

These identified ethnic group differences in the manifestations of depressive symptom led the current authors to ask how much item bias might be found according to different social contexts, particularly caregiver status. Regardless of known significant influences of depression among KA women, our knowledge of the differences in the ways KA women express depression in varying social contexts is very limited. Among the various types of social context, the focus of the present article is caregiver status. Thus, the present study was designed to explore how responses to each item of the CES-D Scale would change depending on caregiver status and thus to identify the invariant items of the CES-D Scale according to different social context.

In this study, we assessed the differences of the CES-D Scale attributable to caregiver status with matched samples of KA caregivers and KA women from the general population. In this way, ethnicity is controlled for (both samples are KA), but the social context of the women’s lives is allowed to vary (caregiver vs. noncaregiver). This analytic approach makes it possible to compare the magnitude of the item differences according to caregiver status.

METHOD

This study compared the DIF of the CES-D Scale between two samples of KA women, caregivers and noncaregivers, by estimating item differences attributable to caregiver status.

Sample and Setting

Approval was obtained from the University Institutional Review Board prior to recruitment and data collection of both samples of KA women.

KA caregivers

The KA caregiver sample and KA noncaregiver sample were collected at different times. Both samples were collected from the Chicago metropolitan area. Data from the KA caregivers were collected in 1998. A purposive sample of KA caregivers (n = 58) was recruited through KA social service agencies, physicians’ offices, churches, adult daycare centers, and long-term institutions by a snowball sampling method. For KA caregivers, inclusion criteria for the subjects were first-generation KAs who were born in Korea, lived in the United States at the time of the data collection, and were able to speak and read Korean. Each subject was the family member who had the major responsibility of providing care on a daily basis to an elderly person who has impairment in any activities of daily living, cognition, or behaviors. Inclusion criteria for KA care recipients were persons who were older than 60 years of age and required daily routine care because of impairment in performing activities of daily living or problems in cognition or behaviors. Care recipients included both male and female subjects.

KA noncaregivers

The KA noncaregivers (n = 300) were recruited through KA community activity centers and Korean YWCA meetings (n = 88), Korean churches (n = 128), workplaces (n = 55), and word-of-mouth strategies (n = 29) in 2005, for a study of barriers to seeking mental health services among KA women. The inclusion criteria of the KA noncaregiver sample were 40 to 69 years old, married, female, immigrated to the United States from Korea after the age of 16 years, and 1 year minimum duration of residence in the United States. This study focused on women aged 40 to 69 years because midlife to older KA women may experience unique barriers to seeking mental health services in the United States. Older KA women report higher levels of psychological distress than younger KA women (Shin, 1993). Potential participants who had a self-reported psychiatric history or had taken antipsychotic medications were excluded to study healthy KA women in the community. Koreans who immigrated to the United States before age 16 experience substantially different adjustment experiences from those who immigrate at older ages (Noh & Avison, 1996), so only women who immigrated after age 16 were recruited for the study. Women who have resided in the United States for less than 1 year were excluded because they did not have enough opportunity to experience the U.S. health care system. Even if the participants were not specifically asked about their caregiving role, the chances of caregivers being included in the sample is extremely low, considering the reported difficulties of recruiting KA caregivers to fill out a survey (Lee, Farran, Tripp-Reimer, & Saddler, 2003). Among the 300 subjects, only 58 KAs were selected for the analysis after using the matching procedure with the caregiver sample.

Procedure for Matching

For the present study, the two samples (KA caregivers and KA noncaregivers) were matched on the CES-D score. The mean total CES-D score of the KA caregivers (mean = 21.53, SD = 12.16) was significantly higher than that of the KA noncaregivers (mean = 6.24, SD = 10.29). To preclude potential group differences in severity of depression, we used a configural matching procedure (Rassler, 2002). Configural matching assures similar distributions in the two groups by selecting one of the two groups (in this case, the one with the smaller sample size) and dividing it into ordered categories based on the total score of the CES-D. In this analysis, we used eight ordered categories, which are called octiles. Then the cases from the second, uncategorized group, were matched up with each of the octiles. In this way, we recreated the same distribution of scores in each matched sample. The process produced a sample of 58 matched pairs of the total CES-D scores. The mean CES-D scores for KA caregivers and the KA noncaregiver group were 21.53 and 20.71, respectively.

The matching process led to selection of individuals with high CES-D scores, however, the demographic characteristics of the individuals from the noncaregiver sample were similar to those in the entire noncaregiver sample, indicating that the individuals selected for this study accurately represented the entire noncaregiver sample. Moreover, the emphasis of the study was to use the configural matching procedure to preclude potential differences in severity of depression between the caregiver and noncaregiver samples.

CES-D Instruments

Two different versions of the CES-D were used for the present study: the CES-D-Korean (CES-D-K) and the revised translated version (CES-D-K-R). The CES-D-K was developed for the Korean immigrant population (Noh, Avison, & Kaspar, 1992). The CES-D-K has established psychometric properties, including reliability and content, construct, and concurrent validity with Koreans in Canada (Noh et al., 1992). Noh, Kaspar, and Chen (1998) revised the translated version of the CES-D-K into the CES-D-K-R by changing the wording of the four items describing positive affect into ones indicating a loss of positive affect. This substitution was done to reduce Asians’ potential bias to not endorse positive feelings, which may be related to the Confucian philosophy of fatalism and emotional self-control (Noh et al., 1998). The reliability and validity were slightly higher in the 20-item CES-D-K-R, with a reliability of .93 compared with .89 in the CES-D-K (Noh et al., 1998).

The CES-D-K (Noh et al., 1992) was used for the KA caregiver sample and was pilot tested with five KA adult caregivers prior to conducting this study. During the pilot test, the Korean translation of the CES-D item, “I felt that I was just as good as other people,” appeared to be problematic because it was translated to “I felt that I was at least as good as other people” (Noh et al., 1992). The two words in the phrase, “least” and “good,” appeared to contradict each other in meaning and cause confusion among the KA caregivers. Therefore, the item was retranslated in Korean to mean, “I felt that I was as good as other people.” The internal consistency reliability of the CES-D-K for the KA caregiver sample was .94. The CES-D-K-R was used in the sample of KA noncaregivers (Noh et al., 1998). The internal consistency reliability of the CES-D-K-R for the KA noncaregiver sample was .96. The two versions of the CES-D were used for the present analysis because the CES-D-K-R was not available when the KA caregiver sample was collected in 1998. We believe that both versions of the CES-D are reliable and valid translations for the Korean-speaking population based on the findings from Noh et al. (1998) using bilingual technique.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis used in this study was MMR, including the effects of age and education in the regression model, using the five steps outlined below:

Construct estimates of the latent trait were made by summing all of the items, save the item undergoing MMR analysis. Thus, if there were 10 items, the first MMR analysis looked at predicting item 1 from the sum of items 2 to 10.

A dummy-coded variable was created to represent the two groups as well as an interaction term that was the product of the group variable and the estimated latent trait.

A multiple regression analysis was conducted with the latent trait, the group variable, and the interaction term as predictors of the item score.

If the interaction term was not significant, it was dropped from the model. The regression was performed again, but only including the latent trait and the group variable.

If the interaction term was significant, then the lower level effects could not be interpreted. To interpret the interaction term, a regression was performed between the latent trait and the item scores separately for each of the groups.

By conducting the five steps of MMR analysis, we estimated the group differences across KA caregivers and KA noncaregivers.

RESULTS

The demographic characteristics of the KA caregivers and KA noncaregivers are summarized in Table 1. No statistically significant differences between the two groups were found for age, length of residence in the United States, or level of education.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Korean American (KA) Caregivers and KA Noncaregivers

| Variables | KA Caregivers (n = 58) | KA Noncaregivers (n = 58) | Test of Group Differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 57.7 (12.4) | 55.1 (9.1) | t = −0.24, not significant |

| Range | 33–85 | 40–69 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | |

| Length of residence (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 18.6 (6.75) | 21.0 (9.8) | t = 0.29, not significant |

| Range | 3.6–41 | 1–38 | |

| Missing | 3 | 1 | |

| Level of education | |||

| High school diploma or less | 32.8% (19) | 43.1% (25) | χ2 = 0.57, not significant |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 15.5% (9) | 20.7% (12) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 46.6% (27) | 36.2% (21) | |

| Missing | 5.2% (3) | 0 |

Differences in CES-D by Caregiver Status

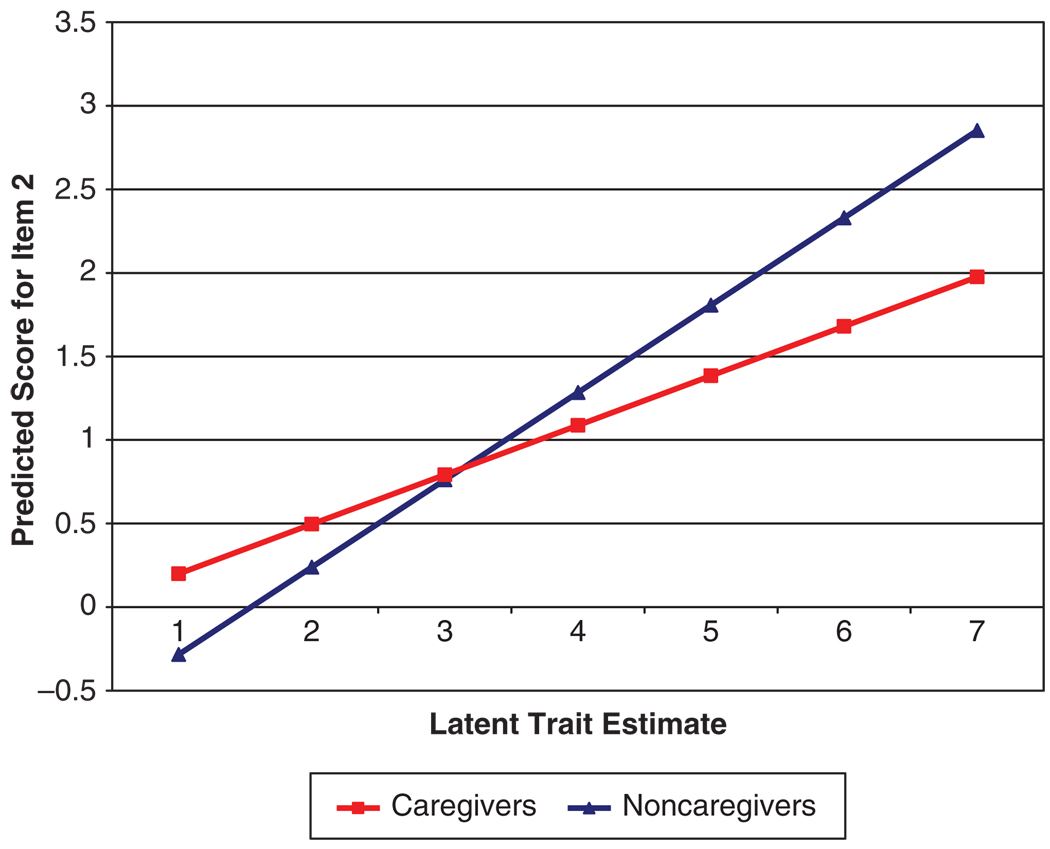

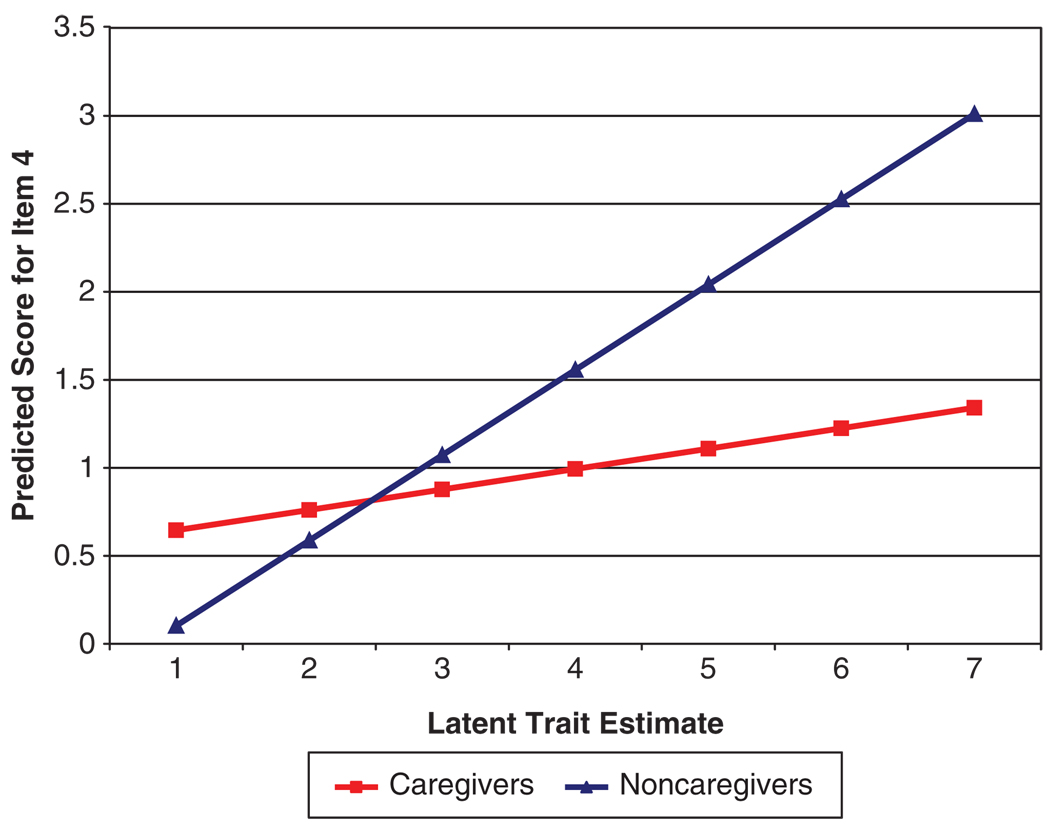

As described earlier, the first MMR model that was examined included an interaction term between the adjusted total score and a dummy-coded group membership variable. Significant interactions between caregiver status and the total CES-D score were observed for 3 of the 20 items: Items 2 (My appetite was poor), 4 (I felt that I was as good as other people), and 14 (I felt lonely). See Figures 1, 2, and 3 for the interaction effects of items 2, 4, and 14, respectively. Feeling lonely was a stronger manifestation of depression for KA caregivers, whereas for KA noncaregivers, a poor appetite and not feeling as good as other people were stronger manifestations of depression.

FIGURE 1.

Group slopes for Item 2—poor appetite

FIGURE 2.

Group slopes for Item 4—as good as others.

FIGURE 3.

Group slopes for Item 14—feeling lonely.

Invariant and Variant CES-D Items

Among the 20 items of the CES-D Scale, three items were found to be variant (attributable to) caregiver status in the present study. In addition to the three variant items identified in the present study, 10 items were found to vary across different ethnic groups in a previous study (Young et al., 2002). Thus seven items were found to be invariant across caregiver status and ethnicity. Table 2 shows the invariant and variant CES-D Scale items identified in the present and the previous studies (Young et al., 2002).

TABLE 2.

Invariant and Variant CES-D Items Based on Four Subscales

| Invariant Items | Variant Items |

|---|---|

| Depressed affect | Depressed affect |

| 3. Unresponsive to help | 9. My life was a failure |

| 6. Felt depressed | 14. Felt lonely |

| 10. Felt fearful | 17. Had crying spells |

| 18. Felt sad | |

| Somatic | Somatic |

| 7. Everything was an effort | 1. Bothered by things |

| 11. Sleep was restless | 2. Poor appetite |

| 20. Could not get going | 5. Trouble concentrating |

| 13. Talked less | |

| Positive affect | |

| 4. Was as good as others | |

| 8. Hopeful about future | |

| 12. Was happy | |

| 16. Enjoyed life | |

| Interpersonal problems | |

| 15. People were unfriendly | |

| 19. People disliked me |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we explored differences in terms of DIF of the CES-D Scale across different social contexts based on caregiver status. The present study revealed significant interactions between caregiver status and total CES-D scores. When response patterns for the CES-D scale were compared for KA caregivers and KA noncaregivers, significant interactions between caregiver status and total CES-D scores were observed in three items: Item 2 (My appetite was poor), 4 (I felt that I was as good as other people), and 14 (I felt lonely). Among caregivers, endorsement of the item about loneliness significantly increased as the total depression score increased, whereas the item about feeling as good as others did not exhibit such a relationship with the total depression score. A possible reason for this phenomenon is the emotional return of caregiving. KA caregivers may feel good about themselves by fulfilling cultural expectations and norms as caregivers. According to previous studies, caregivers reported that caregiving is a rewarding experience and makes them feel useful or proud (Amirkhanyan & Wolf, 2003; Center on Aging Society, 2005, Lee et al., 2003). KA caregivers may maintain a consistent level of self-esteem regardless of the emotional strain they experience. On the other hand, loneliness was found to be a predictor for depression among KA caregivers. Thus, loneliness may be a symptom that requires special attention among KA caregivers, especially because caregiving responsibilities usually leave a minimum amount of time for one to be alone. Among noncaregivers, a poor appetite or not feeling as good as other people significantly increased as the total depression score increased. The endorsement of these items may confirm a primary somatic manifestation or a reluctance to endorse positive emotions among Asian Americans when experiencing depression (Noh et al., 1998).

Besides the 10 CES-D Scale items that have been previously found to be variant across different ethnicity (Young et al., 2002), we identified three items attributable to caregiver status in the present study. As a result, we were able to identify seven invariant items across social roles (caregivers vs. noncaregivers) and ethnic groups. In other words, these seven items helped us to identify the primary manifestations of depression across caregiver status and ethnicity.

Shafer (2006) conducted meta-analysis of the factor structures of four major depression scales: Beck Depression Inventory, CES-D, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale. Based on the analysis, she found that CES-D Scale showed relatively little variability across the studies, which were conducted in different social contexts and ethnic groups compared with the other three depression scales. The CES-D Scale has four main components of depressive affect (7 items), somatic symptoms (7 items), positive affect or wellbeing (4 items), and interpersonal relations (2 items; Radloff, 1977; Shafer, 2006).

Among the seven invariant items which were identified from the present and previous study, four items fit in the depressed affect component: Item 3 (Unresponsive to help), Item 6 (I felt depressed), Item 10 (I felt fearful), and Item 18 (I felt sad). Three items, Item 7 (Everything was an effort), Item 11 (Sleep was restless), and Item 20 (I could not get going), fit in the somatic symptoms component. The present study demonstrates that the depressed affect and somatic symptoms components are the most robust components that are stable across different social contexts as well as ethnicity. Previously, somatic symptoms were found to be reliable indicators of depression, particularly for Asian Americans, including KAs (Arnault & Kim, 2008). None of the interpersonal problems or positive affect items remained invariant (see Table 2). The findings are not surprising when considering the fact that both interpersonal problems and positive affect are strongly influenced by social context (Cuéllar & Paniagua, 2000; Noh et al., 1998). Social context influence beliefs about interpersonal relationships and determine the values, purposes, and rules of those relationships. Acceptable ways to express positive emotions are also determined by social context (Noh et al., 1998). Further studies are needed to explore whether or not these patterns remain consistent across different ethnic groups and social contexts.

One limitation of this study is the time differences between the samples. Changes that occurred to demographic and environment between the two data collection points might have a potential impact on the findings of the present study. Different recruitment strategies and eligibility criteria used for the two samples could also influence the findings. Regardless of the comparability issue, differences between the caregiver and noncaregiver groups were not significant in terms of age, length of residence in the United States, and level of education, indicating that the configural matching process produced a sample of comparably match pairs. It is also important to remember that DIF differences do not usually have an enormous impact on a single individual’s score (Young et al., 2002). Instead, the importance of these differences is in better understanding large-group differences (such as depression rates in the United States and in Korea) and in understanding how the manifestations of depression may vary from one group to another.

Despite the limitation, the present study demonstrated the importance of examining the changes in differential item functioning of the CES-D Scale across different social contexts (caregiver vs. noncaregiver) beyond assessing the level of depression. The findings have significant implications for the use of the CES-D Scale in nursing practice. Knowing that not all items of the CES-D Scale function consistently across social contexts and ethnic groups, we need to assess individual item scores as well as total CES-D Scale scores. In addition, calculating two different summated scores for invariant items and variant items would allow us to examine social and ethnic differences in the symptom endorsement patterns of depression. This study confirmed the importance of inquiring about somatic symptoms when assessing depression in KA women. The present study also showed that findings from well-established and widely used instruments such as the CES-D Scale should be interpreted with caution when the instruments are used for different social contexts and ethnic groups.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed at University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Heeseung Choi, Department of Health Systems Science at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Nursing, Chicago, Illinois; hchoi20@uic.edu.

Louis Fogg, Department of Occupational Therapy at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Applied Health Sciences, Chicago, Illinois.

Eunice E. Lee, Department of Health Systems Science at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Nursing, Chicago, Illinois.

Michelle Choi Wu, Department of Health Systems Science at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Nursing, Chicago, Illinois.

REFERENCES

- Amirkhanyan AA, Wolf DA. Caregiver stress and noncaregiver stress: Exploring the pathways of psychiatric morbidity. Gerontologist. 2003;43:817–827. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.6.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnault DS, Kim O. Is there an Asian idiom for distress? Somatic symptoms in female Japanese and Korean students. Archives in Psychiatric Nursing. 2008;22:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SA, Markides KS, Miller TQ. Correlated of depressive symptomotology among older community dwelling Mexican Americans: The Hispanic EPESE. Journal of Gerontology, Series B, Psychology Sciences and Social Sciences. 1998;53:s198–s208. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.4.s198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center on Aging Society. How do family caregivers fare? A closer look at their experiences. [Retrieved March 5, 2007];2005 from http://ihcrp.georgetown.edu/agingsociety/pdfs/CAREGIVERS3.pdf.

- Cuéllar I. In: Handbook of multicultural mental health: Assessment and treatment of diverse populations. Paniagua FA, editor. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Farran CJ, Miller BH, Kaufman JE, Donner E, Fogg L. Finding meaning through caregiving: Development of an instrument for family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;55:1107–1125. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199909)55:9<1107::aid-jclp8>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelin MN, Zumbo BD. Differential item functioning results may change depending on how an item is scored: An illustration with the center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2003;63:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Holland PW, Wainer H. Differential Item Functioning. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Theis SL. Korean American caregivers: Who are they? Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2000;11:264–273. doi: 10.1177/104365960001100404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MT. Measuring depression in Korean Americans: Development of the Kim Depression Scale for Korean Americans. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2002;13:109–117. doi: 10.1177/104365960201300203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MT, Han HR, Shin HS, Kim KB, Lee HB. Factors associated with depression experience of immigrant populations: A study of Korean immigrants. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2005;19:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Rew L. Ethnic identity, role integration, quality of life, and depression in Korean American women. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1994;8:348–356. doi: 10.1016/0883-9417(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong EH. The influence of culture on the experience of Korean, Korean American, and Caucasian-American family caregivers of frail older adults: A literature review. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2007;37:213–220. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2007.37.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EE, Farran CJ. Depression among Korean, Korean American, and Caucasian American family caregivers. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2004;15:18–25. doi: 10.1177/1043659603260010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EE, Farran CJ, Tripp-Reimer T, Saddler G. Assessing the cultural appropriateness of Finding Meaning Through Caregiving Scale for Korean caregivers. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2003;11:19–28. doi: 10.1891/jnum.11.1.19.52060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Avison WR. Asian immigrants and the stress process: A study of Koreans in Canada. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37:192–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Avison WR, Kaspar V. Depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants: Assessment of a translation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Kaspar V, Chen X. Measuring depression in Korean immigrants: Assessing validity of the translated Korean version of the CES-D Scale. Cross-Cultural Research. 1998;32:358–377. [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Deeb-Sossa N, Harris KM, Bollen K. What are we measuring? An evaluation of the CES-D across race/ethnicity and immigrant generation. Social Forces. 2005;83:1567–1602. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS, Locke B. The community mental health survey and the CES-D scale. In: Weissman M, Myers J, Ross C, editors. Community surveys of psychiatric disorders. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1986. pp. 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Rao CR, Sinharay S. Handbook of statistics: Vol 26. Psychometrics. Amsterdam: North-Holland: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rassler S. Statistical matching: A frequentist theory, practical applications, and alternative bayesian approaches. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves TJ, Bennett CE. We the people: Asians in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2004. (Census 2000 Special Report No. CENSR-17) [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D scale in different ethnic context. Psychiatric Research. 1980;2:125–134. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roxburgh S, Xu Y. Role occupancy, gender, and depression: A comparison of Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic White Americans; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association; Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer AB. Meta-analysis of the factor structures of four depression questionnaires: Beck, CES-D, Hamilton, and Zung. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:123–146. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin KR. Factors predicting depression among Korean-American women in New York. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1993;30:415–423. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(93)90051-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan H, Rogers HJ. Detecting differential item functioning using logistic regression procedures. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1990;27:361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Um CC, Dancy BL. Relationship between coping strategies and depression among employed Korean immigrant wives. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1999;20:485–494. doi: 10.1080/016128499248457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity—A supplement to mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn G, Knight BG, Jeong HS, Benton B. Differences in family values and caregiving outcomes among Korean, Korean American, and White American dementia caregivers. Psychology and Aging. 1999;14:355–364. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.14.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MA, Fogg LF, Choi E. Studying group differences in psychopathology with matched moderated regression. Understanding Statistics. 2002;1:1–12. [Google Scholar]