Abstract

Mammalian glycosphingolipid (GSL) precursor monohexosylceramides are either glucosyl- or galactosylceramide (GlcCer or GalCer). Most GSLs derive from GlcCer. Substitution of the GSL fatty acid with adamantane generates amphipathic mimics of increased water solubility, retaining receptor function. We have synthesized adamantyl GlcCer (adaGlcCer) and adamantyl GalCer (adaGalCer). AdaGlcCer and adaGalCer partition into cells to alter GSL metabolism. At low dose, adaGlcCer increased cellular GSLs by inhibition of glucocerebrosidase (GCC). Recombinant GCC was inhibited at pH 7 but not pH 5. In contrast, adaGalCer stimulated GCC at pH 5 but not pH 7 and, like adaGlcCer, corrected N370S mutant GCC traffic from the endoplasmic reticulum to lysosomes. AdaGalCer reduced GlcCer levels in normal and lysosomal storage disease (LSD) cells. At 40 μm adaGlcCer, lactosylceramide (LacCer) synthase inhibition depleted LacCer (and more complex GSLs), such that only GlcCer remained. In Vero cell microsomes, 40 μm adaGlcCer was converted to adaLacCer, and LacCer synthesis was inhibited. AdaGlcCer is the first cell LacCer synthase inhibitor. At 40 μm adaGalCer, cell synthesis of only Gb3 and Gb4 was significantly reduced, and a novel product, adamantyl digalactosylceramide (adaGb2), was generated, indicating substrate competition for Gb3 synthase. AdaGalCer also inhibited cell sulfatide synthesis. Microsomal Gb3 synthesis was inhibited by adaGalCer. Metabolic labeling of Gb3 in Fabry LSD cells was selectively reduced by adaGalCer, and adaGb2 was produced. AdaGb2 in cells was 10-fold more effectively shed into the medium than the more polar Gb3, providing an easily eliminated “safety valve” alternative to Gb3 accumulation. Adamantyl monohexosyl ceramides thus provide new tools to selectively manipulate normal cellular GSL metabolism and reduce GSL accumulation in cells from LSD patients.

Keywords: Enzyme Inhibitors, Glycolipids, Lysosomal Storage Disease, Shedding, Sphingolipid, Alternative Substrates, GSL Anabolism/Catabolism, Glucocerebrosidase, Glucosyl and Galactosyl Ceramide Analogues, Lactosyl Ceramide/Gb3 Synthases

Introduction

Glycosphingolipid (GSL)2 homeostasis is essential to ensure cellular integrity. GSLs have important functional roles in cell signaling pathways, membrane transport, and cell recognition via intercellular interactions (1, 2). GSLs can modulate membrane receptor function (3, 4), are altered in cancer (5, 6) and cell growth (7), and provide a primary target for host cell interaction with microbial pathogens (8). In addition, GSL accumulation has been identified to contribute to the pathology of many other diseases, including Parkinson disease (9, 10), Alzheimer's disease (11), type 2 diabetes (12, 13), growth factor dysregulation (14), polycystic kidney disease (15), atherosclerosis (16) and cystic fibrosis (17). However, most significantly, defects in GSL catabolism lead to toxic accumulation of GSL substrates and the GSL lysosomal storage disease (LSD) pathologies, a subclass of disorders within the 40 known LSDs (18).

GSL metabolism comprises a complex, branched network of transferases, hydrolases, activators, and trafficking, rendering the process difficult to manipulate selectively. Current therapeutic approaches for LSDs include enzyme replacement therapy, enzyme enhancement therapy, and substrate reduction therapy (SRT) (18). Enzyme replacement therapy uses a recombinant enzyme to compensate for the defective enzyme (19). Although effective in reversing some clinical symptoms, such as organomegaly (20), it is not economically sustainable, with an annual cost over $100,000/patient (21). The recombinant enzyme also cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, rendering this approach ineffective against neurological symptoms (18, 22).

Enzyme enhancement therapy uses small molecules to stabilize a more native conformation of partially misfolded mutant proteins, to avoid endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) and allow traffic to the lysosome (23). One such pharmacological chaperone in clinical trials is isofagomine, an inhibitor of glucocerebrosidase (β-glucosylceramidase (GCC)) that rescues enzyme activity in Gaucher disease (GD) cells, which suffer from glucosylceramide (GlcCer) accumulation due to defective catabolism (24). The utility of this approach extends only to misfolding mutants, and, given the many mutations that may compromise folding, many different agents may be required (25, 26).

SRT involves inhibition of GlcCer synthase to reduce the total GSL content (23). Its utility extends to LSDs involving neurological symptoms because the inhibitors are able to cross the blood-brain barrier. However, SRT is subject to unwanted side effects, especially at the more effective higher doses, where additional inhibition of glucosidases may occur (27). N-butyl-deoxynojirimycin is an SRT agent approved for use by GD patients and has been shown to be effective in reversing organomegaly but suffers from low efficacy (28, 29). Other inhibitors of GlcCer synthase include 1-phenyl-2-decanoylamino-3-morpholino-1-propanol (30) and subsequent improvements with enhanced selectivity (31, 32). These inhibitors are non-carbohydrate mimics of GlcCer, and the most recent derivative shows much promise for the selective depletion of all GSLs (33).

Inhibition of GlcCer synthase offers the opportunity to modulate the other disease processes in which GSLs play a role. However, such inhibition depletes cells of all GSLs, not just the offending accumulated species. Approaches that more selectively deplete a single GSL or subset of GSLs may avoid side effects resulting from total GSL ablation. As a first step toward this goal, we have made GSL inhibitors to selectively target the two key precursor GSLs of GSL biosynthesis.

We have previously made amphipathic analogues of GSLs by substituting the fatty acid moiety with an adamantane frame. These adamantyl GSLs (adaGSLs) show a major increase in water solubility while retaining receptor function of the parent GSL in solution (34). Adamantyl Gb3, a soluble mimic of globotriaosyl ceramide, Gb3 (35), preferentially partitions into aqueous phase, as opposed to organic solvents, which completely sequester Gb3. Unlike the water-soluble, lipid-free Gb3 oligosaccharide, adaGb3 retains high affinity verotoxin (VT) binding in aqueous solution (35) and indeed shares some properties of Gb3-cholesterol complexes in solution (36), which may relate to its several bioactivities (37, 38). Exchange of the GSL fatty acid moiety for adamantane also proved effective to generate a water-soluble, ligand-binding, bioactive mimic of sulfogalactosyl ceramide (sulfatide) (39–41), suggesting that this could represent a general method for the generation of soluble bioactive GSL mimics.

AdaGSLs are amphipathic mimics that retain receptor function (42) and are taken up by living cells (41). We investigated whether adaGSLs can partition into cells and alter cellular GSL metabolism.

GSL biosynthesis is essentially based on the synthesis of two precursor GSLs, GlcCer, upon which 90% of GSLs are based, and GalCer (43). In this study, we characterize two GSL analogues, adamantyl glucosylceramide (adaGlcCer) and adamantyl galactosylceramide (adaGalCer), in terms of their effects on cellular GSL metabolism. These analogues serve as inhibitors and alternative substrates to redirect cellular GSL metabolism in a selective, targeted manner and are a new means to control aberrant GSL turnover. These and similar adaGSLs provide an approach to manipulate cellular GSL metabolism for the selective depletion of a single GSL or GSL series.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Sodium hydroxide, 1-adamantaneacetic acid, dimethylformamide, triethylamine, dichloromethane, cold water fish gelatin, 4-chloro-1-naphthol, MgCl2, dithiothreitol, sucrose, MnCl2, 4-methylumbelliferyl β-d-glucopyranoside, resorcinol, DMSO, benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy-tris-(dimethylamino)-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate (BOP), and saponin were all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. UDP-[3H]galactose and [14C]galactose were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse and goat-anti-rabbit antibodies were from Bio-Rad. DAPI, Alexa fluor 488 chicken anti-rabbit IgG for GCC, and Alexa fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG for LAMP-1 or protein disulfide isomerase CHCl3 were obtained from Molecular Probes.

Methanol, silica, and Tris base were obtained from Caledon Laboratory Chemicals. All tissue culture reagents (HEPES, 1× RPMI, Eagle's minimal essential medium, DMEM/F-12, α-modification of Eagle's minimal essential medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin/streptomycin, Dulbecco's PBS, and normal goat serum) were purchased from Wisent, Inc. Verotoxin (VT1) was purified as described previously (42). The LAMP-1 antibody was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD, National Institutes of Health, and maintained by the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA).

The following reagents were purchased from the source indicated in parentheses: HCl (Fisher), C18 Sep-pak (Waters), thin layer chromatography (TLC) plates (Macherey-Nagel Inc.), 30% H2O2 (EM Science), bovine buttermilk GlcCer (Matreya, LLC), NH4OAc (BioShop Canada, Inc.), conduritol β-epoxide (Toronto Research Chemicals), paraformaldehyde (EMS), mouse monoclonal anti-rat PDI (Stressgen Bioreagents).

Adamantyl Glycosphingolipid Synthesis

20 mg of bovine buttermilk glucosylceramide was dried and incubated in a P2O5 chamber overnight. GlcCer was deacylated in 10 ml of 1.0 m NaOH (methanolic) at 72 °C over 4 days to form lyso-GlcCer. The reaction mixture was neutralized with 5–6 m HCl. Solvent was removed on a rotary evaporator to a thick, syrupy liquid, which was dissolved in water and passed through a C18 column to desalt. Lyso-GlcCer was eluted with methanol and then applied to a silica column in CHCl3/CH3OH (98:2, v/v). Lyso- GlcCer eluted with CHCl3/CH3OH/H2O (90:10:0.5, v/v/v).

A 0.5 m solution of 1-adamantaneacetic acid and a 0.25 m solution of BOP were prepared in dimethylformamide/dichloromethane/triethylamine (5:5:1, v/v/v). Lyso-GlcCer (20 mg; 43.4 μmol; 2.17 μmol/mg) was redissolved in 0.5 ml of 5:5:1. 130 μmol of 0.5 m 1-adamantaneacetic acid was added to 1.5 ml of 5:5:1, and the tube was cooled to −70 °C in a dry ice/ethanol bath. To this was added 108 μmol of BOP. After incubating for 10 min at −70 °C, lyso-GlcCer was added to the reaction tube, and the reaction was allowed to proceed at −70 °C for 1.5 h. The reaction was stopped by raising to room temperature, followed by the addition of 10 ml of H2O. Dichloromethane was removed under a stream of nitrogen. Product mixture was desalted by C18 chromatography and purified by a silica column. AdaGlcCer eluted with 90:10:0.5 CHCl3/CH3OH/H2O. The reaction scheme was identical for synthesis of adaGalCer.

Mass Spectroscopic Analysis

Mass spectra were recorded on a QSTARXL spectrometer with an o-MALDI source (ABI/MDS Sciex, Concord, Canada). Sample was mixed with an equal volume of DHB and was spotted on a MALDI plate. Compounds were dissolved in CH3OH-NaCl solution that was prepared by adding a saturated solution of aqueous NaCl to LC-MS Chromasolv® methanol.

Cell Culture

Normal, Fabry disease (FD), and GD patient lymphoblasts and skin fibroblasts (kindly provided by Dr D. Mahuran (Research Institute, Hospital for Sick Children)) were maintained in 1× RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10 or 15% FBS and 1 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin. For cell treatments, cells were grown in medium containing 10, 20, or 40 μm adaGSL or 2 μm d-threo-1-ethylendioxyphenyl-2-palmitoylamino-3-pyrrolidinopropanol (P4) for 3 or 4 days. For untreated cells, ethanol was added to the medium, up to the highest volume of adamantyl analog used, for a final concentration of 0.4% (v/v). Vero (African green monkey kidney epithelial) and Daoy (human medulloblastoma) cells were maintained in Eagle's minimal essential medium, supplemented with 5% FBS and antibiotics (as above). BHK (hamster kidney) cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12, supplemented with 5% FBS. Normal and FD fibroblasts were cultured in α-modification of Eagle's minimal essential medium, supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics (as above). For metabolic labeling studies, treatments were for 3 days, with the addition of 1.5 μCi of [14C]galactose, fresh adaGSL, and/or fresh medium on day 3 for 24 h. Alternatively, cells were pretreated for 3 h, followed by culture with fresh analog and [14C]galactose overnight.

GSL Extraction

Adherent cells were washed, trypsinized, counted, and then pelleted at 1200 × g for 9 min and washed in PBS. Total cellular lipids were extracted in CHCl3/CH3OH (2:1, v/v) with shaking for 3 or 24 h. For total GSL preparations, extracts were passed through glass wool to filter cellular debris and dried under nitrogen. For neutral GSLs, a Folch partition (CHCl3/CH3OH/H2O, 2:1:0.6) of the extracts was performed, and the lower phase was dried under nitrogen. Phospholipids were saponified with 0.5 ml of 0.5 m methanolic NaOH for 1 h at 37 °C or overnight at room temperature. Extracts were neutralized with 0.5 ml of 0.1 m methanolic NH4OAc and 0.5 ml of 0.5 m HCl. For total GSL extraction, methanol was diluted to <20% with water, and the preparation was applied to a C18 column. Salts were removed with water, and GSLs were eluted with 5 ml of CH3OH, followed by 3 ml of CHCl3/CH3OH (2:1). Eluates were pooled, dried, and resuspended in CHCl3/CH3OH (2:1) equivalent to 105 cells/μl.

TLC and VT1 Overlay

The GSL extract from an equivalent of 106 adherent cells or 2 × 106 lymphoblasts was applied to a TLC plate and separated in CHCl3/CH3OH (98:2), followed by CHCl3/CH3OH/H2O (65:25:4 or 140:60:11, v/v/v). Brief iodine staining of sphingomyelin was used as an internal loading control. Iodine stain was removed by brief heating. GSLs were then visualized by spraying TLC plates with orcinol and heating at 110 °C until bands appeared.

For ganglioside isolation, acidic GSLs were separated by first passing total GSL extract through a DEAE-Sephadex column. Neutral GSLs were eluted with methanol washes, and acidic GSLs were eluted with 0.25 m methanolic NH4OAc. Acidic GSLs were desalted by C18 column chromatography. An extract from an equivalent of 1.5 × 106 cells was separated by TLC first in 98:2 CHCl3/CH3OH and then 55:45:10 (CHCl3/CH3OH/0.25% KCl). The plate was lightly sprayed with resorcinol/HCl and heated at 110 °C out of air contact until ganglioside bands appeared.

For VT1 overlays (44), GSLs from an equivalent of 0.5–1 × 106 cells were separated by TLC. Plates were dried and blocked with 1% fish gelatin in 50 mm Tris-buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.4, for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C. Plates were washed with TBS and then incubated with 0.35 μg/ml VT1 B subunit in TBS for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C. After washing in TBS, plates were incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-VT1B antibody. Plates were washed in TBS and then incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody. VT1-bound GSLs were visualized with a 3 mg/ml solution of 4-chloro-1-naphthol in methanol mixed with 5 volumes of TBS and 0.015% H2O2.

GSLs were quantified and compared by densitometry using ImageJ. GSL intensities were normalized with the intensity of the sphingomyelin internal control.

α-Galactosidase Assay

Lactosylceramide (LacCer), galabiosylceramide (Gb2), and medium GSL extracts were mixed with 50 μl of 1% (w/v) taurodeoxycholate and dried under nitrogen. Samples were resuspended in 200 μl of 50 mm sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0, 2 mm EDTA, 1% BSA) and sonicated.

GSLs were digested with 0.5 units of coffee bean α-galactosidase at 37 °C for 4 h. An additional 0.5 units was added to one medium extract at 4 h, and H2O was added to the other, and incubation of all reactions was continued overnight (45).

Sulfatide Detection

TLC overlay immunoassay was performed as described previously (46) with some modifications. Briefly, GSL extract dissolved in CHCl3/CH3OH (2:1) was separated by TLC first in 98:2 CHCl3/CH3OH and then in 60:35:8 CHCl3/CH3OH/H2O. The plate was dried using a hair dryer, treated with a solution of polyisobutylmethacrylate for 5 min, dried, and treated with polyisobutylmethacrylate for an additional 3 min. The plate was blocked with 1% BSA-TBS for 30 min and incubated with 1 μg/ml Sulf1 antibody (47) overnight at room temperature. Following washing, the plate was incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody for 1 h and then washed and visualized by electrochemiluminescence.

Cell-free Glycosyltransferase Assay

Vero cells were washed, scraped, and counted. Cells were centrifuged at 1200 × g, and the supernatant was discarded. Cells were resuspended in homogenization buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm dithiothreitol, 0.5 m sucrose) and were Dounce homogenized with 35 strokes. Homogenate was collected and centrifuged at 4 °C and 800 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was centrifuged at 4 °C and 100,000 × g for 80 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in buffer (100 mm HEPES, 0.05% Triton X-100, 0.5 m sucrose) and centrifuged at 4 °C and 800 × g for 10 min. The resulting supernatant (microsomal fraction) was kept at −80 °C until required. Protein quantitation was performed using the BCA assay (Pierce).

A master mix composed of 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.7, 10 mm MnCl2, 0.3 μCi/reaction UDP-[3H]galactose, and H2O was prepared. GlcCer, LacCer, and adaGSL were prepared by mixing with Triton (0.3% (w/v) final concentration per reaction) and drying under nitrogen, followed by redissolving in water. 30 μg of GlcCer or LacCer and/or 40 μm adaGSL and/or water was added to microcentrifuge tubes, followed by 70 μl of master mix and 30 μg of enzyme (i.e. microsomal fraction). Tubes were incubated at 37 °C with agitation for 3 h, after which contents were transferred to glass tubes containing CHCl3/CH3OH (2:1). The neutral GSL extraction procedure was followed, as described above.

Inhibition of Glucocerebrosidase

Compounds (adaGlcCer, adaGalCer, conduritol β-epoxide) were dissolved in DMSO to a concentration of 7.5 mm for adaGSLs and 500 mm for conduritol β-epoxide (CBE). A 3-fold serial dilution of the adamantyl GSLs from 7.5 mm to 10 μm was prepared. CBE concentrations of 500, 250, 100, 40, 16, 6.4, and 2.5 mm were prepared.

An inhibition assay was performed as previously reported (48). Briefly, 1 μl of GSL analog was added in each well of one column in a 96-well plate, and DMSO was added to one well. 25 μl of 5 mm 4-methylumbellilferyl glucopyranoside fluorescent substrate was added to each well, followed by 25 μl of either 1.24 μg/ml GCC (Cerezyme®) in pH 5 citrate phosphate (CP) buffer (McIlvaine buffer) or 0.62 μg/ml in pH 7 CP buffer. Wells with CP buffer only (blank substrate) were also included. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min; thereafter, 200 μl of 0.1 m 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol was added to stop the reaction. Fluorescence intensities were measured using a Spectramax Gemini EM MAX (Molecular Devices Corp.) fluorometer and detected at excitation and emission wavelengths set to 365 and 450 nm, respectively.

Glucocerebrosidase Assay

Bovine buttermilk GlcCer and adaGlcCer were mixed with 1% taurodeoxycholate and dried under nitrogen. These were resuspended in 80 μl of pH 5 or 7 CP buffer, followed by the addition of either buffer or 0.24 μg of Cerezyme®, and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Reaction was stopped by Folch partition. The upper phase was removed, and the lower phase was washed twice with CH3OH/H2O (1:1). The lower phase was dried, resuspended in 2:1, and separated by TLC in 90:10:0.5 CHCl3/CH3OH/H2O, followed by iodine and orcinol detection.

Indirect Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy Imaging

Indirect immunolabeling was performed using a previously described protocol (49) with small modifications. In brief, cells were seeded at low density onto 18-mm diameter coverslips for about 16 h and then washed and fixed with 2.5% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.2, for 30 min at 37 °C. Blocking and permeabilization was performed for 1 h at room temperature with 0.2% saponin and 10% normal goat serum in phosphate-buffered saline with calcium and magnesium (SS-PBS). Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in SS-PBS and overlaid on the coverslips for 1 h at room temperature; secondary antibodies were similarly overlaid for 1 h in the dark at room temperature; and extensive washes with PBS were performed after primary and secondary antibody incubations. Nuclear staining was done with DAPI at 1:50,000 in PBS. Coverslips were mounted onto glass slides using fluorescent anti-fading mounting medium (DakoCytomaton). Primary antibodies used were rabbit polyclonal IgG anti-human β-glucocerebrosidase (a gift from Dr. D. Mahuran), mouse monoclonal IgG1 anti-human LAMP-1, and mouse monoclonal anti-rat PDI. Secondary antibodies were Alexa fluor 488 chicken anti-rabbit IgG for GCC and Alexa fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG for LAMP-1 or PDI at a 1:200 dilution in SS-PBS. Samples were analyzed using a Zeiss Axiovert confocal laser microscope equipped with a ×63, 1.4 numerical aperture Apochromat objective (Zeiss) and LSM 510 software; DAPI-stained nuclei were detected on the same system with a Chameleon two-photon laser. To provide a qualitative estimate of GCC levels from the fluorescent signals, the same confocal microscope settings were maintained throughout all confocal sessions for the same pair of primary antibodies (GCC plus LAMP-1 or GCC plus PDI). Confocal images were imported, and contrast/brightness was adjusted using the Volocity 5 program (Improvision Inc.). A representative cell is shown for each set of staining.

GCC Western Blot

Normal and GD fibroblasts were treated with or without 40 μm adaGlcCer or adaGalCer for 4 days. Cells were washed and trypsinized and then pelleted at 1200 × g for 10 min and washed in PBS. Cells were suspended in lysis buffer (PBS, 0.1% taurodeoxycholate) and lysed by five cycles of alternately freezing (in a bath of dry ice/ethanol) and thawing (37 °C water bath). Suspension was centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Total cellular protein was quantitated by a BCA assay. 30 μg of protein lysate was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane at 100 V for 70 min. Membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk TBS-Tween (M-TBST) for 1 h, followed by incubation with 1:1000 (in M-TBST) rabbit anti-human GCC (kindly provided by Dr. D. Mahuran) overnight at 4 °C. Membrane was incubated with 1:10,000 donkey anti-rabbit HRP for 1 h, followed by ECL detection.

Extracellular GSL Content Analysis

Following treatment of GD and normal patient lymphoblasts with adaGalCer for 4 days, the growth medium was lyophilized overnight. Contents were redissolved in water, and a Folch partition was performed. The neutral GSL isolation procedure was then followed, as described above. The GSL extract from an equivalent of 2 × 106 cells was separated by TLC and visualized by orcinol or VT binding.

RESULTS

AdaGSL Synthesis

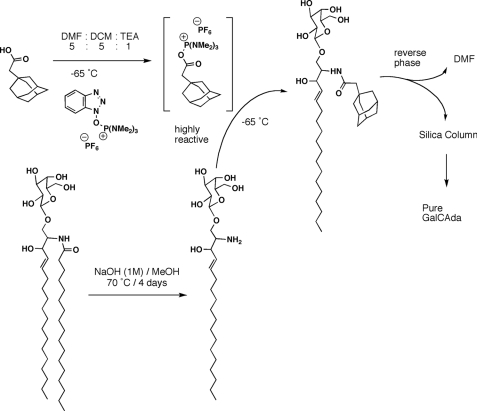

The reaction scheme for synthesis of adaGalCer is shown in Fig. 1. Product yield was ∼90%. Following synthesis and purification of the products, MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was performed to verify the identity of the product (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1.

AdaGalCer reaction scheme. GalCer (shown) or GlcCer was deacylated by NaOH treatment over 4 days to form lyso-GSL. Purified lyso-GSL was coupled to BOP-activated adamantane acetic acid. Resulting adaGSL was purified by C18 and silica column chromatography, with an overall reaction yield of ∼90%. DMF, dimethylformamide; DCM, dichloromethane; TEA, triethylamine.

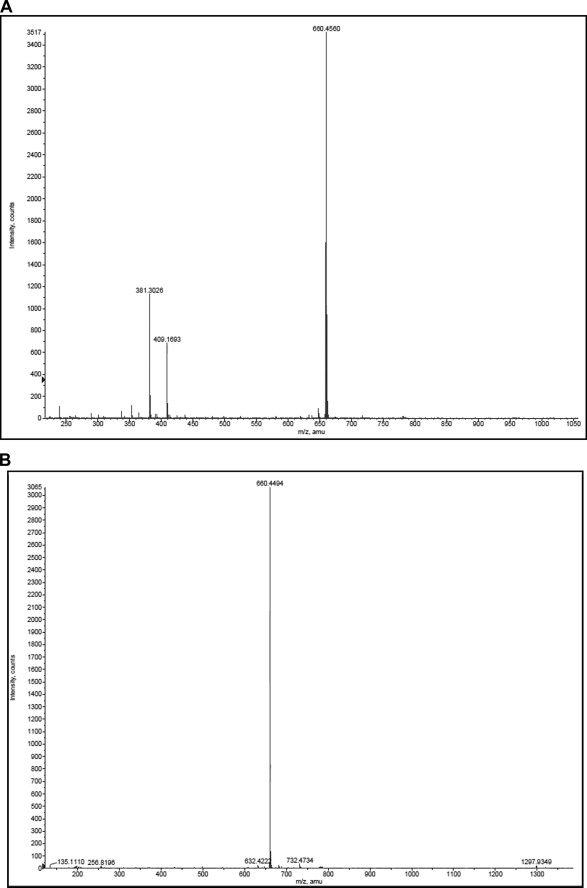

FIGURE 2.

Mass spectrometry analysis of adaGlcCer (A) and adaGalCer (B). Purified adaGSL was dissolved in sodium-saturated methanol, and the MALDI-TOF mass spectrum was determined. A single molecular ion (660) was seen for adaGalCer. This was the major species for adaGlcCer also, but additional peaks, probably due to alkyl chain heterogeneity (-CH2) of the starting material, were also present.

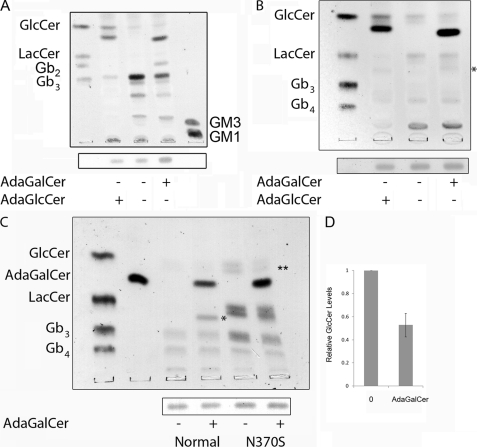

AdaGlcCer and AdaGalCer Treatment Alter Cellular GSL Levels

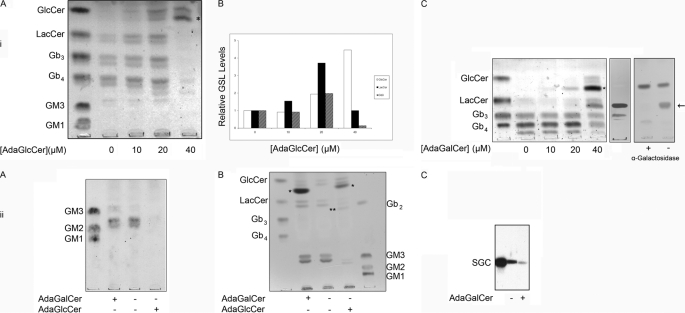

Vero cells were treated with adaGSLs at three different doses for 3 days, and the effect on GSL content was determined (Fig. 3i, A–C). 10 and 20 μm adaGlcCer resulted in elevated levels of all neutral GSLs. In contrast, a major reduction in all GSLs downstream of GlcCer was observed at 40 μm. GlcCer levels were further elevated at the higher dose.

FIGURE 3.

AdaGSL effects on cellular GSLs. Vero cells were treated with 10, 20, or 40 μm adaGlcCer (i, A) or adaGalCer (i, C) for 4 days, followed by neutral GSL extraction and separation by TLC. Ethanol (0.4% (v/v) final concentration) was used as a vehicle-only control. GSL levels for adaGlcCer-treated cells were quantified and compared by densitometry (i, B). Low doses of adaGlcCer increased cellular GSLs, whereas 40 μm treatment reduced all GSLs downstream of GlcCer, which was further increased. 40 μm adaGalCer reduced globo series GSLs and resulted in formation of a new GSL species. The middle panel in i, C, shows VT1/TLC overlay of 40 μm extract. The right panel shows an orcinol-stained TLC following incubation of conditioned medium (containing adaGb2) with or without α-galactosidase. α-Galactosidase was able to cleave adaGb2. ii, A, resorcinol staining of acidic GSLs from Daoy cells treated with or without adaGlcCer or adaGalCer. Gangliosides are eliminated after adaGlcCer treatment but unaffected by adaGalCer treatment (ii, B). Total GSL extract from BHK cells treated with or without 40 μm adaGlcCer or adaGalCer for 3 days is shown. Neutral and acidic GSLs are unaltered by adaGalCer but significantly reduced following adaGlcCer treatment. ii, C, anti-sulfatide binding to the TLC-separated GSLs from BHK cells treated with or without 25 μm adaGalCer for 3 days. AdaGalCer treatment reduces cellular sulfatide levels. First lane, sulfatide standard. * and **, adaGSL substrate and adaGSL product, respectively; arrow, adaGb2; SGC, 3′-sulfogalactosyl ceramide.

AdaGalCer had little effect below 20 μm, but at 40 μm, a marked reduction of globo series GSLs (Gb3 and Gb4) was seen, whereas GlcCer and LacCer accumulated (Fig. 3i, C). Furthermore, the presence of a new species was observed at this dose. This new GSL was bound by VT and was susceptible to α-galactosidase, indicating a terminal galactose α1–4-galactose motif. This was characterized by mass spectrometry as adaGb2 (supplemental Fig. S1).

AdaGalCer was also found to have no effect on gangliosides in Daoy cells (Fig. 3ii, A) or BHK cells (Fig. 3ii, B), whereas 40 μm adaGlcCer resulted in ablation of both neutral and acidic GSLs. In BHK cells, an alternative product consistent with adaLacCer was detected.

In addition, 25 μm adaGalCer lowered BHK cell levels of sulfatide (3′-sulfogalactosyl ceramide), but no alternative product was detected (Fig. 3ii, C). (In contrast, adamantyl 3′-sulfogalactosyl ceramide (41) increased cell sulfatide levels; data not shown).

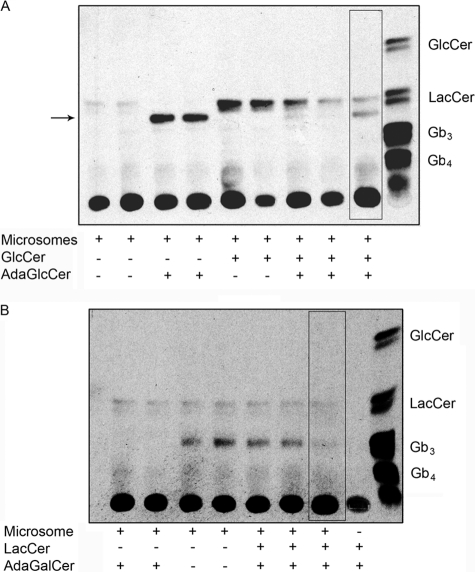

AdaGlcCer and AdaGalCer Inhibit Microsomal LacCer and Gb3 Synthase, Respectively

LacCer was the major endogenous microsomal GSL product (Fig. 4A). Synthesis of LacCer was reduced in the presence of adaGlcCer, and an alternative product, probably adaLacCer, was made. Exogenous GlcCer increased LacCer synthesis, which was competed out by adaGlcCer. Likewise, adaLacCer synthesis from adaGlcCer was competed out by the addition of exogenous GlcCer. Pretreatment of microsomes with adaGlcCer increased production of adaLacCer and reduced synthesis of LacCer from exogenous GlcCer.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of AdaGSLs on cell-free GSL synthesis assay. Microsomes prepared from Vero cells were incubated with 30 μg of exogenous GlcCer and/or 40 μm adaGlcCer (A) or 30 μg of exogenous LacCer and/or 40 μm adaGalCer (B), and the synthesis of LacCer and Gb3, respectively, was monitored by UDP-[3H]galactose incorporation for 3 h. The outlined lane denotes pretreatment of microsomes with adaGSL for 3 h, prior to the addition of radiolabel. LacCer was synthesized from endogenous GlcCer. A new radiolabeled product (arrow; probably adaLacCer) was formed from adaGlcCer, and LacCer synthesis was inhibited. Exogenous GlcCer increased LacCer synthesis, whereas its synthesis was reduced in the presence of adaGlcCer. Conversely, product from adaGlcCer was less in the presence of exogenous GlcCer, but preincubation with adaGlcCer partially restored this product formation. B, adaGalCer did not significantly reduce Gb3 synthesis from exogenous LacCer unless microsomes were pretreated with adaGalCer. AdaGb2 formation was not detected.

In contrast, adaGalCer did not reduce endogenous LacCer synthesis but reduced Gb3 synthesis from exogenous LacCer, particularly after pretreatment of microsomes with adaGalCer (Fig. 4B). However, microsomal adaGb2 synthesis was not detected.

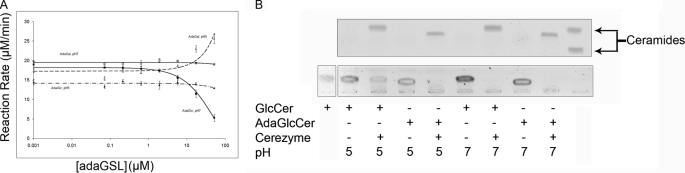

AdaGlcCer Inhibits, but AdaGalCer Stimulates, Glucocerebrosidase Activity in Vitro

Using recombinant enzyme, we tested, in vitro, if adaGlcCer prevents GlcCer catabolism by GCC inhibition. AdaGlcCer had no effect on GCC activity at pH 5 but inhibited GCC activity at pH 7 at adaGlcCer concentrations >5 μm (Fig. 5A). In contrast, adaGalCer had no effect at pH 7 but stimulated GCC activity at pH 5. Increased enzyme activity was seen at adaGalCer concentrations as low as 2 μm and continued through the entire range of concentrations examined. CBE, a covalent inhibitor of the lysosomal glucosylceramidase (50), showed a dose-dependent inhibition at both pH 5 and 7 (data not shown). GlcCer was cleaved more effectively at pH 7, whereas adaGlcCer was deglucosylated by recombinant enzyme equally well at pH 5 and 7 (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of AdaGSLs on in vitro GCC. A, GCC was assayed using pH 5 or 7 citrate-phosphate buffer, Cerezyme®, a fluorescent substrate analog (4-methylumbelliferyl glucopyranoside), and adaGlcCer, adaGalCer, or conduritol β-epoxide (not shown). Fluorescent substrate was excited at 365 nm, and emission was recorded at 450 nm. AdaGlcCer had no effect on enzyme activity at pH 5 but showed inhibition at pH 7, whereas adaGalCer had a stimulatory effect at pH 5 and no effect at pH 7. ▴, adaGlcCer, pH 5.0; ■, adaGlcCer, pH 7.0; △, adaGalCer, pH 5.0; □, adaGalCer, pH 7.0. B, GlcCer or adaGlcCer was incubated in the absence or presence of Cerezyme® at pH 5 or 7, and the lipid extracts from the reaction were separated by TLC and stained with iodine (top), followed by orcinol (bottom). AdaGlcCer and GlcCer were degraded by the enzyme at both pH values, but adaGlcCer cleavage was more effective than GlcCer at pH 5.

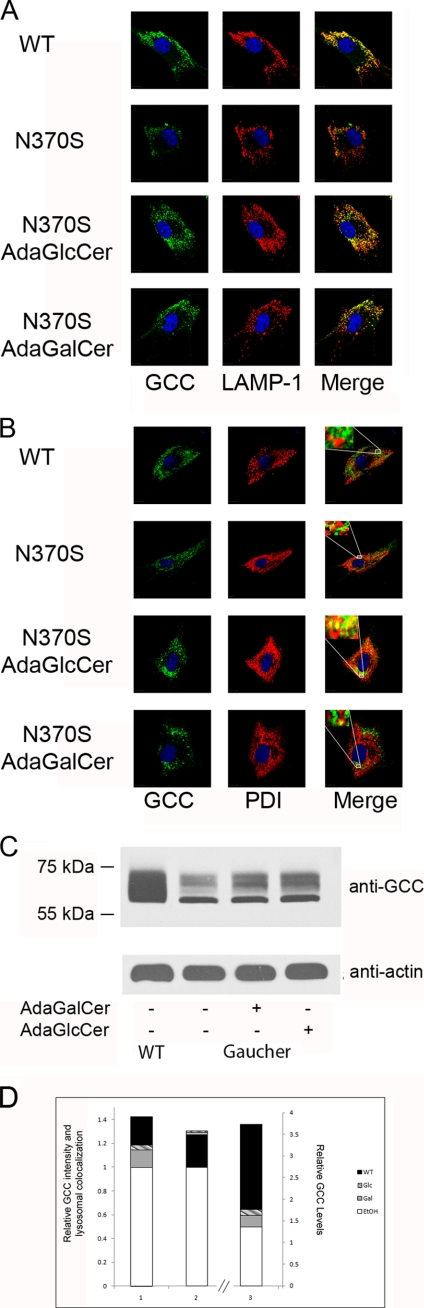

AdaGSLs Facilitate Transport of N370S Glucocerebrosidase to the Lysosome

To determine if adaGlcCer or adaGalCer can chaperone mutant glucocerebrosidase, GD (homozygous N370S) patient skin fibroblasts were treated with 40 μm adaGalCer, 40 μm adaGlcCer or mock-treated with ethanol for 3 days, transferred to coverslips, and immunostained for GCC, LAMP-1, or PDI (Fig. 6). Normal human skin fibroblasts were used as a control. Confocal microscopy showed considerable overlap between GCC fluorescence signal and the lysosomal marker LAMP-1 in normal fibroblasts (Fig. 6A). Signal intensity was substantially less in (mock treated) GD cells, with noticeable separation between the intracellular localization of GCC and LAMP-1. AdaGalCer or adaGlcCer treatment enhanced overall GCC signal intensity and markedly increased the coincidence of GCC and LAMP-1 to a pattern indistinguishable from WT cells. The increased GCC-LAMP-1 colocalization was measured by quantitative analysis of 11 confocal microscopy images. In adaGalCer- or adaGlcCer-treated GD cells, GCC lysosomal targeting was greater than in WT cells (Fig. 6D).

FIGURE 6.

AdaGlcCer, adaGalCer correction of N370S GCC trafficking in Gaucher disease cells. A, comparison of intracellular localization of GCC (green) relative to the lysosomal compartment marker LAMP-1 (red) in WT and N370S GD fibroblasts. WT fibroblasts show strong colocalization of both proteins in lysosomes as seen by the degree of punctate yellow pattern in the merged image (right panels). In contrast, N370S display a lower level of GCC (decreased green signal) and of colocalization (decreased yellow signal). Treatment of N370S with either adaGSL increases the level of GCC (green signal levels; quantitated in D) and its localization to the lysosomal compartment as denoted by the level of yellow in the two lower merge panels (quantitated in D). B, comparison of intracellular localization of GCC (green) relative to the ER compartment marker PDI (red) in WT and N370S GD fibroblasts. In N370S GD fibroblasts, GCC colocalizes with PDI (degree of yellow signal in merge panel) but not wild-type fibroblasts. Treatment of N370S with adaGalCer increases the level of GCC (intensity of green levels) and strongly decreases its colocalization with PDI (compare level of yellow in merge panels). AdaGlcCer treatment shows some colocalization of GCC and PDI. C, Western blot for GCC in GD and normal fibroblasts. Cells were treated for 4 days with 40 μm adaGlcCer or 40 μm adaGalCer. GCC levels were increased in treated GD fibroblasts but remained considerably lower than normal fibroblasts (quantitated in D). D, relative change in GCC staining, lysosomal colocalization, and expression. Intensity of GCC staining in WT and adaGSL-treated N370S cells was measured, normalized for area, and compared with staining in untreated N370S cells using Volocity 5 (Improvision Inc.) (column 1). GCC staining was greater for adaGalCer (gray) and adaGlcCer (hatched) compared with untreated cells (open). Staining was significantly higher in WT (t(20) = 3.43, p < 0.05). GCC colocalization with LAMP-1 was quantitated by applying Manders' coefficient, Mx (column 2). Lysosomal GCC colocalization for WT (Mx = 0.773, S.D. = 0.0871) as well as adaGlcCer-treated (Mx = 0.793, S.D. = 0.0840) and adaGalCer-treated (Mx = 0.783, S.D. = 0.0512) mutant GD cells was significantly higher than in untreated mutant cells (Mx = 0.605, S.D. = 0.0716) at p < 0.05. GCC expression examined by Western blot was quantitated (column 3, secondary y axis). Enzyme expression was increased following adaGSL treatment but still lower than WT.

In WT cells, the fluorescence signals for GCC and the ER marker PDI did not colocalize (Fig. 6B). However, in N370S GD fibroblasts, GCC signal colocalizes with PDI. After adaGlcCer treatment, a significant amount of GCC signal in GD remains colocalized with PDI; in contrast, after adaGalCer treatment, GCC signal localization becomes distinct from that of PDI, similar to the pattern observed in WT.

A Western blot for GCC in normal and N370S GD fibroblasts was performed to assess whether the relocation of N370S GCC by adaGSL treatment protects against ERAD. Consistent with co-chaperone function, the level of GCC protein (immature and mature, as determined by glycosylation-dependent molecular weight differences) in N370S fibroblasts was increased following cell treatment with 40 μm adaGalCer or adaGlcCer (Fig. 6C) by ∼2-fold. However, GCC activity in the lysate of adaGalCer-treated GD or wild type lymphoblasts using 4-methyl umbelliferyl glucose substrate was not increased (supplemental Fig. S2).

AdaGalCer Reduces GlcCer in Gaucher Disease Cells

Because adaGalCer was found to activate GCC, correct the N370S GCC lysosomal trafficking defect, and decrease N370S GCC depletion by ERAD, the effect of adaGalCer on GlcCer accumulation in GD cells was examined. A reduction in GlcCer levels was seen following treatment of GD fibroblasts (Fig. 7A) or lymphoblasts (Fig. 7, B and C) with 40 μm adaGalCer. This effect on GlcCer levels was quantitated by image analysis, and the data were pooled to show an overall 50% inhibition by adaGalCer (Fig. 7D). As for Vero cells (and FD cells; see below) Gb3 and Gb4 were also depleted. AdaGalCer had no effect on ganglioside content (Fig. 7A). AdaGlcCer depleted GD cells of all GSLs except GlcCer, which was further elevated.

FIGURE 7.

AdaGalCer reduces GlcCer in Gaucher disease cells. GD fibroblasts (A) or lymphoblasts (B and C) were treated with or without 40 μm adaGlcCer or adaGalCer for 4 days, followed by GSL extraction, TLC separation, sphingomyelin detection by iodine (lower bar, A–C), and GSL staining by orcinol. AdaGlcCer substantially reduced GSL levels except for GlcCer, which was elevated. AdaGalCer treatment reduced cellular GlcCer and resulted in adaGb2 formation to reduce Gb3. C, normal (lanes 3 and 4) and GD lymphoblasts (lanes 5 and 6) were left untreated or treated with 40 μm adaGalCer. GlcCer levels are reduced in GD cells treated with adaGalCer. D, GlcCer levels in all treated and untreated GD cells were compared by densitometry. * and **, adaGb2 and GlcCer, respectively.

To further verify adaGalCer reduction of GlcCer, [14C]GlcCer accumulated in Gaucher or Fabry disease lymphoblasts by adaGlcCer treatment was determined after adaGlcCer wash out and treatment with either adaGalCer or adaGlcCer (supplemental Fig. S3). GlcCer accumulation was far more marked in GD compared with Fabry cells. AdaGalCer reduced accumulated GlcCer levels in Fabry disease (FD) but not GD cells, whereas adaGlcCer further increased GlcCer in both cell types.

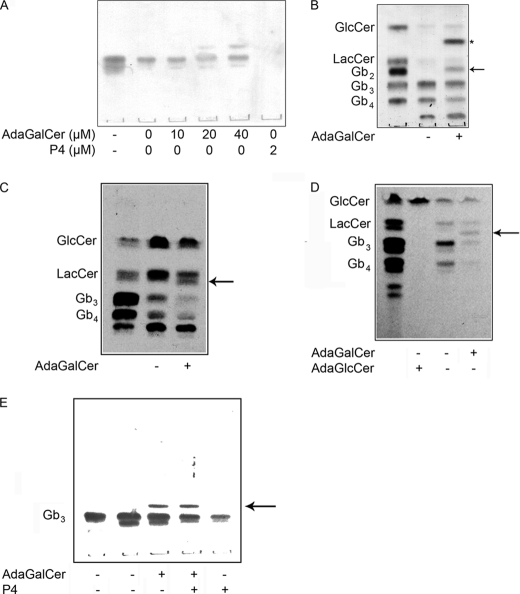

AdaGalCer Prevents Gb3 Synthesis in FD Cells

Because adaGalCer provides an alternative substrate for Vero cell Gb3 synthase to reduce cellular globo series GSL content, the utility of this approach as a strategy to lower Gb3 in FD cells was assessed. However, total Gb3 levels from FD lymphoblasts treated with adaGalCer were only slightly reduced (Fig. 8, A and B), although increasing levels of adaGb2 were detected with increasing adaGalCer. As a positive control, cells were also treated with the GlcCer synthase inhibitor, P4 (32), resulting in a substantial decrease in Gb3.

FIGURE 8.

AdaGalCer reduces Gb3 synthesis in Fabry disease cells. A, Verotoxin TLC overlay of GSLs extracted from 106 untreated FD lymphoblasts treated for 3 days with 10, 20, or 40 μm adaGalCer or 2 μm P4. VT-bound Gb3 levels were unaltered by adaGalCer, and adaGb2 was detected, whereas P4 treatment eliminated Gb3. B, orcinol-stained GSLs from 106 control or 40 μm adaGalCer-treated FD lymphoblasts. Gb3 levels were reduced, but less effectively than Gb4. C, metabolic labeling of GSLs from FD lymphoblasts. Untreated radiolabeled cellular GSLs were compared by autoradiography to GSLs from cells treated with 40 μm adaGalCer for 3 days, followed by the addition of [14C]galactose and fresh adaGalCer for 24 h. Synthesis of Gb3 and Gb4 was significantly reduced (by ∼70%). D, metabolic labeling of GSLs from FD fibroblasts. GSLs from FD cells with or without 40 μm adaGlcCer or adaGalCer were separated by TLC and compared by autoradiography. Cells were left untreated or treated with adaGSL for 3 h prior to the addition of [14C]galactose and fresh adaGSL overnight. AdaGlcCer completely inhibits GSL synthesis, and GlcCer accumulates. In adaGalCer-treated cells, adaGb2 is produced, and Gb3/Gb4 synthesis is reduced by ∼90%. E, co-treatment of FD fibroblasts with adaGalCer and P4. Gb3 was detected by VT TLC overlay. Co-treatment results in FD cell Gb3 levels intermediate between P4 and adaGalCer treatment. The asterisk denotes adaGalCer, and the arrow indicates adaGb2.

Metabolic labeling was used to assess whether Gb3 synthesis is inhibited by adaGalCer. Normal and FD lymphoblasts were treated with adaGalCer for 3 days, and then [14C]galactose and fresh adaGalCer were added for 24 h. Neutral GSLs were extracted and detected by TLC and autoradiography (Fig. 8C). [14C]Gb3 and [14C]Gb4 levels in treated cells were significantly reduced relative to untreated cells. The additional VT-reactive species (adaGb2) seen in Vero cell treatments was also detected in FD lymphoblasts and fibroblasts (Fig. 8, C and D) treated with adaGalCer, indicating competitive inhibition of Gb3 synthase. FD lymphoblasts have high synthesis rates for GlcCer and LacCer, which were reduced by adaGalCer, indicating that GCC activation also occurs in these cells.

The effect of adaGlcCer on FD fibroblast GSL synthesis was also determined by a 3-h preincubation, followed by culture with radiolabel with or without adaGSL overnight. Synthesis of GSLs downstream of GlcCer was completely prevented by this brief adaGlcCer treatment (Fig. 8D).

AdaGalCer Reduces Gb3 Turnover

Because FD cell Gb3 synthesis was inhibited by adaGalCer treatment, without equivalent reduction in total Gb3 levels, the possible inhibition of the (defective) Gb3 catabolism in these cells was examined by combining adaGalCer treatment with P4. P4 severely diminished FD cell Gb3 levels, but co-treatment of FD fibroblasts (Fig. 8E) or lymphoblasts (data not shown) with adaGalCer decreased the extent of Gb3 reduction by P4. This is consistent with adaGalCer inhibition of residual α-galactosidase activity in these cells.

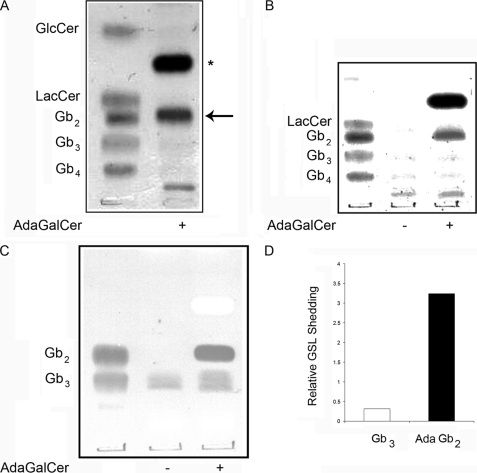

Soluble Adamantyl GSL Products Are Preferably Shed from Cells

The ability of the alternative adaGSL product, adaGb2, to be released from cells was addressed by examining the GSL content of the conditioned medium from adaGalCer-treated cells. Fig. 9 shows the presence of a prominent adaGb2 species by TLC of the extracellular GSLs for both normal and GD lymphoblasts. AdaGb2 was present in 3-fold excess in the extracellular medium relative to intracellular levels, whereas Gb3 was found to be in 3-fold excess intracellularly. Thus, there is at least a 9-fold preference for adamantyl GSL shedding.

FIGURE 9.

AdaGb2 is preferentially shed into extracellular media. Conditioned media were lyophilized, and the neutral GSLs were extracted and separated by TLC for both normal (A) and GD (B and C) lymphoblasts cultured with adaGalCer. GSLs were visualized by orcinol staining (A and B) or VT overlay (C). Cellular and medium adaGb2 and Gb3 levels for normal lymphoblasts were compared by densitometry (D). Although more non-polar, as monitored by TLC migration, accumulation of adaGb2 in the medium was approximately 10-fold that of Gb3. The asterisk and arrow indicate adaGalCer and adaGb2, respectively. The lower species in A and B is probably GM3 ganglioside.

DISCUSSION

Using adaGalCer and adaGlcCer, we have found that adamantyl GSL mimics offer powerful new physiologically based tools to more selectively regulate cellular GSL levels.

AdaGalCer Selectively Inhibits Globoseries GSL Synthesis in Normal and Fabry Disease Cells

For adaGalCer, there was no obvious effect on Vero cell GSL levels <20 μm. At 40 μm, however, there was a selective reduction in globo series GSLs and a variable corresponding increase in GlcCer and LacCer levels, whereas GM3 ganglioside levels were largely unaltered. In addition, a new dihexoside species was identified. Because this species was bound by VT1 (which binds GSLs containing terminal galactose α1–4-galactose), this new GSL was considered to be adaGb2, which was corroborated by mass spectrometry. The decrease in globo series GSLs can, therefore, be ascribed to substrate competition for Gb3 synthase by adaGalCer (i.e. adaGalCer competes with LacCer). This is based on the premise that the α-galactosyltransferase that synthesizes Gb3 from LacCer is the same that uses GalCer as a substrate to make Gb2 (51), and that adaGalCer can serve as an alternative substrate to GalCer, to form the new GSL, adaGb2. In this way, adaGalCer reduces synthesis of Gb3 in favor of adaGb2. Importantly, alternative product formation suggests an increased substrate efficacy of adaGalCer for the α-galactosyltransferase.

Indeed, we have seen adaGb2 production in cells with little detectable Gb3. Levels of sulfatide, the 3′-sulfate ester of GalCer, were also reduced by adaGalCer, further attesting to the ability of adaGalCer to modulate GSL metabolic enzymes based on GalCer. In this case, no alternative product was formed.

The adamantane frame in our analogues plays a central role. Treating cells with lyso-GalCer (deacylated GalCer) <26 μm had no effect on GSL levels (data not shown). 40 μm lyso-GalCer was toxic, whereas adaGSLs showed no toxicity. The adamantane confers increased water solubility (42), but membrane solubility of the analogues is retained. Thus, the adaGSL is able to partition into the plasma membrane and traffic to the Golgi (and lysosome) to provide an enzyme inhibitor or alternative substrate. Products from such adaGSL substrates retain the amphipathic character of the substrate analog and are preferentially lost from the cell. In normal lymphoblasts, adaGb2 was preferentially released from cells and was present in 3-fold excess in the growth medium relative to cells, compared with at least a 3-fold excess of Gb3 in cells relative to the extracellular medium. Thus, adaGb2 is ∼10-fold more easily shed from cells than GSLs, such as Gb3, which, according to TLC migration, is more polar than adaGb2 (but not water-soluble). The ease of shedding may also reflect reduced interaction of adaGSLs with cholesterol, known to associate with GSLs in membrane microdomains.

This offers the potential for the development of a titratable “safety valve” approach to substrate reduction therapy of GSL storage diseases, allowing the alternative product to “bleed” out of the cell without intracellular accumulation while retaining partial or even normal synthesis of the native GSL to maintain normal function.

The reduction of Gb3 levels by adaGalCer treatment of FD lymphoblasts was less effective than in Vero cells, despite synthesis of adaGb2. Because FD cell Gb3 was lost after P4 treatment, these cells must contain sufficient residual α-galactosidase activity for this catabolism. Because metabolic labeling showed that Gb3 and Gb4 synthesis were significantly reduced by adaGalCer in FD cells, adaGalCer may further reduce the low level of α-galactosidase activity in these cells, perhaps mediated by the adaGb2 generated. Concurrent incubation of FD fibroblasts with adaGalCer and P4 restores Gb3 to an intermediate level, consistent with adaGalCer inhibition of both synthesis and degradation of Gb3. α-Galactosidase inhibition can also provide a chaperone approach to Fabry disease rescue (23).

The inhibitory effects of both adaGSLs are quite rapid; 3-h preincubation of FD fibroblasts with the analogues, followed by overnight labeling, showed major reduction of GSL synthesis downstream of GlcCer using adaGlcCer and inhibition of Gb3 (and Gb4) synthesis, together with formation of adaGb2, using adaGalCer.

AdaGlcCer both Stimulates and Inhibits GSL Synthesis

At lower doses (10–20 μm), adaGlcCer resulted in elevated levels of all cellular GlcCer-based GSLs. A method for the stimulation of cellular GSL synthesis has not been described previously, and it should be a useful adjunct to study GSL function. For example, GSL synthesis provides an escape from ceramide-induced apoptosis (53) for increased cell survival (5). The mechanism of this stimulation remains to be defined. Because adaGlcCer inhibited GCC at pH 7 but not pH 5, inhibition of GlcCer catabolism by Golgi GCC en route to lysosomes could be an explanation.

However, at 40 μm adaGlcCer, a complete reversal and major reduction in all GSLs downstream of GlcCer was seen. This provides a new benign means to shut down GSL synthesis. We attributed this dichotomy to competitive inhibition of the catabolic GCC by low adaGlcCer concentrations and competitive inhibition of the anabolic LacCer synthase at higher concentration in addition to continued catabolic inhibition. At the lower doses, decreased degradation of GlcCer would provide increased substrate for synthesis of downstream GSLs. At higher doses, inhibition of LacCer synthesis would reduce synthesis of these downstream GSLs and further increase GlcCer. Thus, at high adaGlcCer, GlcCer becomes essentially the only cellular GSL. AdaGlcCer should, therefore, also provide a useful tool to study the role of GlcCer in intracellular vesicular traffic (54).

Vero cell-free micosomal GSL synthesis confirmed 40 μm adaGlcCer as a competitive LacCer synthase inhibitor, as far as we are aware the first to be described. In our microsomal assay, adaGlcCer was converted to an alternative product, probably adaLacCer. This could be outcompeted by the addition of more LacCer, verifying the reversibility of LacCer synthase inhibition. AdaLacCer was not detectable in Vero cells, but if made, it would be preferentially secreted, similar to adaGb2. In contrast, microsomal adaGb2 synthesis from adaGalCer was not detected, despite its ready detection in cells. The basis of this clear distinction between the formation of adamantyl ceramide dihexosides in cells versus microsomes treated with adaGlcCer or adaGalCer remains to be resolved, but it could result from adaGSL access to the GSL biosynthetic machinery due to a differential Golgi location of Gb3 synthase and LacCer synthase. In BHK cells, adaLacCer was formed, suggesting that product formation from the adaGlcCer-LacCer synthase complex is variable. Microsomal synthesis of Gb3 was only decreased by pretreatment of microsomes with adaGalCer, without adaGb2 detection. The lack of alternative product synthesis may be due to the short incubation time because Gb3 synthesis was reduced only by adaGalCer pretreatment. It is plausible that adaGalCer binds to Gb3 synthase, but reaction kinetics for conversion to adaGb2 may be slow in a cell-free environment. Also, the presence of Triton in the microsome assay may alter the relative availability of native and adamantyl GSL substrates.

Both AdaGalCer and AdaGlcCer Affect GCC

AdaGlcCer inhibition of GCC was tested with recombinant enzyme. Our results show inhibition at pH 7 but no effect at pH 5. GCC trafficking in cells involves Limp-2 and is mannose 6-phosphate-independent (55). Mutation in the enzyme may lead to misfolding and degradation by the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway (56, 57), to define the severity of Gaucher disease. Our results suggest that adaGlcCer may affect GCC during traffic from the ER to the lysosome. The pH-dependent inhibition by adaGlcCer might be useful in enzyme enhancement therapy. AdaGlcCer could potentially bind to (and inhibit) mutant GCC in the ER to stabilize the enzyme and allow traffic to the lysosome, as found for other glycohydrolase inhibitors (24, 58, 59) where inhibition is lost, an optimum therapeutic stratagem.

Recombinant GCC (Cerezyme®) was able to degrade adaGlcCer to adamantyl Cer and glucose at both pH 7 and pH 5, but GlcCer degradation was not quantitative at pH 5. Thus, adaGlcCer is a better GCC substrate than GlcCer. This could be a function of the increased solubility of adaGlcCer. How the elevated cellular GlcCer level following adaGlcCer treatment relates to its selective inhibition of GCC at neutral pH is unclear. Inhibition of LacCer synthase may be the primary effect.

In the GCC assay, CBE provided a positive inhibition control, and adaGalCer was tested as a negative control. Whereas CBE showed the expected inhibition, adaGalCer surprisingly enhanced GCC activity at pH 5, suggesting a potential allosteric activation site. This remains to be defined but is consistent with reduced GlcCer levels found in adaGalCer-treated normal, GD, and FD cells.

An allosteric activation of Cerezyme® GCC by adaGalCer is consistent with our finding that adaGalCer could rescue N370S GD GCC from ERAD and remedy its mislocation within the ER to traffic to lysosomes. Accumulation of N370S GCC in the ER was effectively reduced by adaGalCer. Indeed, the N370S GD GCC colocalization with the LAMP-1 lysosomal marker after adaGalCer treatment was, if anything, greater than that seen for wild-type GCC. However, although the mature N370S GCC, a function of glycosylation-dependent apparent molecular weight change, was increased by either adaGalCer or adaGlcCer cell treatment, the level remained less than wild type. The fact that lysosomal targeting of N370S GCC after adaGalCer treatment became greater than wild type indicates that “immature” glycosylated GCC is also redirected to lysosomes, consistent with mannose 6-phosphate independence (55).

Because adaGalCer activated Cerezyme® at pH 5 and rescued N370S GCC from ERAD to target it to lysosomes, the potential of adaGalCer to reverse the GlcCer accumulation characteristic of Gaucher disease(60, 61) was assessed by treating GD primary cells. AdaGalCer reduced GD GlcCer levels by approximately half (in addition to inhibition of Gb3 synthesis). This effect, in fact, was more notable in FD fibroblasts in which abnormally high levels of labeled GlcCer (and LacCer) were markedly reduced by adaGalCer. This indicates that adaGalCer traffics to both the Golgi (to inhibit Gb3 synthase) and the lysosome, the acidic site for GCC activation.

Thus, after adaGalCer rescue of N370S GD GCC from ERAD and redirection to the lysosome, adaGalCer should activate N370S GD GCC. This would provide an optimum combination of benefits to reduce GlcCer levels for potential GD therapy. However, we were unable to show adaGalCer activation of N370S or WT GCC activity in treated cell lysates or by direct addition to cell lysate, using the 4-MU-glucose substrate assay (supplemental Fig. S2), despite induced N370S GCC lysosomal targeting and reduced GlcCer levels in adaGalCer-treated cells. AdaGlcCer-induced accumulated GlcCer was reduced by adaGalCer in FD but not GD cells (supplemental Fig. S3), suggesting that adaGalCer enhancement may be greater for Cerezyme® > WT GCC > N370S GCC. The increased efficacy of adaGalCer to reduce GlcCer levels in Fabry cells may relate to the abnormal trafficking of exogenous GSLs to lysosomes in Fabry but not Gaucher disease cells (62), increasing Fabry lysosome adaGalCer content. AdaGalCer may stabilize rather than activate GCC in cells, and the artificial assay may be inadequate to detect enhanced activity. The distinction between the effect on Cerezyme® and WT cell enzyme in situ remains to be clarified but identifies potentially useful allosteric regulation.

We have shown that cell membrane GSLs can be, in large part, masked from ligand binding by cholesterol (63, 64), due to a cholesterol-induced conformational change in GSL carbohydrate to become parallel to the membrane (11, 64). AdaGSLs do not interact with cholesterol (studies in progress) and should therefore, be resistant to such cholesterol masking. Cholesterol present in the Golgi (65) might similarly affect GSL enzyme substrate presentation to restrict/regulate GSL metabolism, providing an advantage for adamantyl GSLs, to explain the preferential substrate/inhibitor properties we have observed for these GSL mimics in cells.

The ability of adaGSLs to regulate different steps in GSL biosynthesis presents a more selective means to evaluate the biological function or pathology of a GSL than the elimination of all glucosylceramide-based GSLs achieved by glucosylceramide synthase inhibitors, the only current alternative.

CONCLUSION

Our study shows the potential for adamantyl GSLs as novel, benign means to selectively modulate cellular GSL metabolism, with potential clinical utility. We have probed this potential with adaGlcCer and adaGalCer, primary precursor GSL analogues. These provide the means to target selective early steps in GSL metabolism to investigate GSL function and prevent pathologic GSL accumulation. AdaGalCer could be a viable strategy for Fabry disease, if initiated early, by serving as an alternative substrate for Gb3 synthase, generating a readily eliminated alternative product while maintaining “normal” Gb3 levels, and for Gaucher disease, by chaperoning mutant glucocerebrosidase and activating Cerezyme®. Adamantyl mimics of branch point GSLs may similarly divert GSL metabolism for other GSL storage diseases and pathologies characterized by aberrant GSL metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. H.-J. Park for sulfatide immunostaining.

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research team grant in Lysosomal Storage Disease Pharmaco-therapeutics.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- GSL

- glycosphingolipid

- adaGSL

- adamantyl GSL

- P4

- d-threo-1-ethylendioxyphenyl-2-palmitoylamino-3-pyrrolidinopropanol

- GCC

- glucocerebrosidase

- LSD

- lysosomal storage disease

- SRT

- substrate reduction therapy

- ERAD

- endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation

- GlcCer

- glucosylceramide

- GalCer

- galactosylceramide

- LacCer

- lactosylceramide

- Gb2

- digalactosylceramide

- adaGb2

- adamantyl digalactosylceramide

- Gb3

- globotriaosylceramide

- Gb4

- globotetraosylceramide

- adaGlcCer

- adamantyl glucosylceramide

- adaGalCer

- adamantyl galactosylceramide

- BOP

- benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy-tris-(dimethylamino)-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate

- CBE

- conduritol β-epoxide

- GD

- Gaucher disease

- VT

- verotoxin

- FD

- Fabry disease

- CP

- citrate phosphate

- PDI

- protein disulfide isomerase

- GM1

- monosialogangliotetraosyl ceramide

- GM2

- monosialogangliotriaosyl ceramide

- GM3

- monosialolactosyl ceramide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hakomori S., Igarashi Y. (1995) J. Biochem. 118, 1091–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sillence D. J. (2007) Int. Rev. Cytol. 262, 151–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nishio M., Fukumoto S., Furukawa K., Ichimura A., Miyazaki H., Kusunoki S., Urano T., Furukawa K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 33368–33378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yoon S. J., Nakayama K., Hikita T., Handa K., Hakomori S. I. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 18987–18991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bieberich E. (2004) Glycoconj. J. 21, 315–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kovbasnjuk O., Mourtazina R., Baibakov B., Wang T., Elowsky C., Choti M. A., Kane A., Donowitz M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 19087–19092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chatterjee S., Kolmakova A., Rajesh M. (2008) Curr. Drug Targets 9, 272–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lloyd D. H., Viac J., Werling D., Rème C. A., Gatto H. (2007) Vet. Dermatol. 18, 197–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manning-Boğ A. B., Schüle B., Langston J. W. (2009) Neurotoxicology 30, 1127–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Velayati A., Yu W. H., Sidransky E. (2010) Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 10, 190–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yahi N., Aulas A., Fantini J. (2010) PLoS One 5, e9079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tagami S., Inokuchi Ji J., Kabayama K., Yoshimura H., Kitamura F., Uemura S., Ogawa C., Ishii A., Saito M., Ohtsuka Y., Sakaue S., Igarashi Y. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3085–3092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yew N. S., Zhao H., Hong E. G., Wu I. H., Przybylska M., Siegel C., Shayman J. A., Arbeeny C. M., Kim J. K., Jiang C., Cheng S. H. (2010) PLoS One 5, e11239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kawashima N., Yoon S. J., Itoh K., Nakayama K. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6147–6155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Natoli T. A., Smith L. A., Rogers K. A., Wang B., Komarnitsky S., Budman Y., Belenky A., Bukanov N. O., Dackowski W. R., Husson H., Russo R. J., Shayman J. A., Ledbetter S. R., Leonard J. P., Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O. (2010) Nat. Med. 16, 788–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bietrix F., Lombardo E., van Roomen C. P., Ottenhoff R., Vos M., Rensen P. C., Verhoeven A. J., Aerts J. M., Groen A. K. (2010) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 931–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Norez C., Antigny F., Noel S., Vandebrouck C., Becq F. (2009) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 41, 217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heese B. A. (2008) Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 15, 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Van der Ploeg A. T., Kroos M. A., Willemsen R., Brons N. H., Reuser A. J. (1991) J. Clin. Invest. 87, 513–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barton N. W., Brady R. O., Dambrosia J. M., Di Bisceglie A. M., Doppelt S. H., Hill S. C., Mankin H. J., Murray G. J., Parker R. I., Argoff C. E. (1991) N. Engl. J. Med. 324, 1464–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burrow T. A., Hopkin R. J., Leslie N. D., Tinkle B. T., Grabowski G. A. (2007) Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 19, 628–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoffmann B., Mayatepek E. (2005) Neuropediatrics 36, 285–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fan J. Q. (2008) Biol. Chem. 389, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Steet R. A., Chung S., Wustman B., Powe A., Do H., Kornfeld S. A. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13813–13818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pastores G. M., Lien Y. H. (2002) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, Suppl. 2, S130–S133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hruska K. S., LaMarca M. E., Scott C. R., Sidransky E. (2008) Hum. Mutat. 29, 567–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Butters T. D., Dwek R. A., Platt F. M. (2005) Glycobiology 15, 43R-52R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cox T., Lachmann R., Hollak C., Aerts J., van Weely S., Hrebícek M., Platt F., Butters T., Dwek R., Moyses C., Gow I., Elstein D., Zimran A. (2000) Lancet 355, 1481–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Futerman A. H., Hannun Y. A. (2004) EMBO Rep. 5, 777–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Radin N. S., Shayman J. A., Inokuchi J. I. (1993) in Advances in Lipid Research (Bell R. M., Hannun Y. A., Merrill A. H., Jr. eds) pp. 183–213, Academic Press, Inc., San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abe A., Inokuchi J., Jimbo M., Shimeno H., Nagamatsu A., Shayman J. A., Shukla G. S., Radin N. S. (1992) J. Biochem. 111, 191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee L., Abe A., Shayman J. A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14662–14669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McEachern K. A., Fung J., Komarnitsky S., Siegel C. S., Chuang W. L., Hutto E., Shayman J. A., Grabowski G. A., Aerts J. M., Cheng S. H., Copeland D. P., Marshall J. (2007) Mol. Genet. Metab. 91, 259–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lingwood C., Sadacharan S., Abul-Milh M., Mylvaganum M., Peter M. (2006) Methods Mol. Biol. 347, 305–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mylvaganam M., Lingwood C. A. (1999) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 257, 391–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mahfoud R., Mylvaganam M., Lingwood C. A., Fantini J. (2002) J. Lipid Res. 43, 1670–1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lund N., Branch D. R., Mylvaganam M., Chark D., Ma X. Z., Sakac D., Binnington B., Fantini J., Puri A., Blumenthal R., Lingwood C. A. (2006) AIDS 20, 333–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. De Rosa M. F., Ackerley C., Wang B., Ito S., Clarke D. M., Lingwood C. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 4501–4511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mamelak D., Mylvaganam M., Tanahashi E., Ito H., Ishida H., Kiso M., Lingwood C. (2001) Carbohydr. Res. 335, 91–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Whetstone H., Lingwood C. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 1611–1617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Park H. J., Mylvaganum M., McPherson A., Fewell S. W., Brodsky J. L., Lingwood C. A. (2009) Chem. Biol. 16, 461–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lingwood C. A., Sadacharan S., Abul-Milh A., Mylvaganam M., Peter M. (2006) in Methods Mol. Biol. (Brockhausen I. ed) Vol. 347, pp. 305–320, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Meer G., Holthuis J. C. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1486, 145–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nutikka A., Binnington-Boyd B., Lingwood C. A. (2003) Methods Mol. Med. 73, 197–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bailly P., Piller F., Cartron J. P., Leroy Y., Fournet B. (1986) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 141, 84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Colsch B., Baumann N., Ghandour M. S. (2008) J. Neuroimmunol. 193, 52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fredman P., Mattsson L., Andersson K., Davidsson P., Ishizuka I., Jeansson S., Månsson J. E., Svennerholm L. (1988) Biochem. J. 251, 17–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rigat B., Mahuran D. (2009) Mol. Genet. Metab. 96, 225–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Birmingham C. L., Brumell J. H. (2006) Autophagy 2, 156–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Grabowski G. A., Osiecki-Newman K., Dinur T., Fabbro D., Legler G., Gatt S., Desnick R. J. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 8263–8269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kojima Y., Fukumoto S., Furukawa K., Okajima T., Wiels J., Yokoyama K., Suzuki Y., Urano T., Ohta M., Furukawa K. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 15152–15156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Deleted in proof.

- 53. Gouaze-Andersson V., Cabot M. C. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758, 2096–2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sillence D. J., Puri V., Marks D. L., Butters T. D., Dwek R. A., Pagano R. E., Platt F. M. (2002) J. Lipid Res. 43, 1837–1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Reczek D., Schwake M., Schröder J., Hughes H., Blanz J., Jin X., Brondyk W., Van Patten S., Edmunds T., Saftig P. (2007) Cell 131, 770–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ron I., Horowitz M. (2005) Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 2387–2398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sawkar A. R., Schmitz M., Zimmer K. P., Reczek D., Edmunds T., Balch W. E., Kelly J. W. (2006) ACS Chem. Biol. 1, 235–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Asano N., Ishii S., Kizu H., Ikeda K., Yasuda K., Kato A., Martin O. R., Fan J. Q. (2000) Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 4179–4186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fan J. Q., Ishii S., Asano N., Suzuki Y. (1999) Nat. Med. 5, 112–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brady R. O., Kanfer J. N., Shapiro D. (1965) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 18, 221–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Grabowski G. A. (2008) Lancet 372, 1263–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chen C. S., Patterson M. C., Wheatley C. L., O'Brien J. F., Pagano R. E. (1999) Lancet 354, 901–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mahfoud R., Manis A., Binnington B., Ackerley C., Lingwood C. A. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 36049–36059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lingwood D., Binnington B., Róg T., Vattulainen I., Grzybek M., Coskun U., Lingwood C. A., Simons K. (2011) Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 260–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mukherjee S., Zha X., Tabas I., Maxfield F. R. (1998) Biophys. J. 75, 1915–1925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.