Abstract

In adult rat brains, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) rhythmically oscillates according to the light-dark cycle and exhibits unique functions in particular brain regions. However, little is known of this subject in juvenile rats. Here, we examined diurnal variation in BDNF and neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) levels in 14-day-old rats. BDNF levels were high in the dark phase and low in the light phase in a majority of brain regions. In contrast, NT-3 levels demonstrated an inverse phase relationship that was limited to the cerebral neocortex, including the visual cortex, and was most prominent on postnatal day 14. An 8-h phase advance of the light-dark cycle and sleep deprivation induced an increase in BDNF levels and a decrease in NT-3 levels in the neocortex, and the former treatment reduced synaptophysin expression and the numbers of synaptophysin-positive presynaptic terminals in cortical layer IV and caused abnormal BDNF and NT-3 rhythms 1 week after treatment. A similar reduction of synaptophysin expression was observed in the cortices of Bdnf gene-deficient mice and Ca2+-dependent activator protein for secretion 2 gene-deficient mice with abnormal free-running rhythm and autistic-like phenotypes. In the latter mice, no diurnal variation in BDNF levels was observed. These results indicate that regular rhythms of BDNF and NT-3 are essential for correct cortical network formation in juvenile rodents.

Keywords: Akt PKB, Neurodevelopment, Neurotrophic Factor, Neurotrophin, Synapses, BDNF, NT-3

Introduction

BDNF2 and neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) are widely distributed in the adult CNS and exhibit unique functions in particular regions, in addition to their general neurotrophic activities (1, 2). Recently, it has been reported that BDNF is expressed rhythmically according to the light-dark (LD) cycle in the cerebellum (Cbl), the hippocampus (Hip), and the cerebral neocortex (NCX) as well as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in adult rats (3–8). In particular, BDNF in the NCX oscillates with a unique cycle, suggesting that neurons are still active in the sleeping phase (8). Regarding the effects of an abnormal LD cycle, a phase advance of the cycle decreases BDNF levels in a majority of brain regions in adult rats 1 week after treatment, leading to depression of neuronal activity (8). Moreover, it has been shown that chronic jet lag leads to atrophy of the human temporal cortex and that light deprivation damages monoamine neurons, producing a depressive behavioral phenotype in rats (9, 10). Thus, in adulthood, diurnal BDNF rhythms seem to contribute to the regulation of particular brain functions. To date, the issues whether there are diurnal rhythms of BDNF (and/or NT-3) levels in the developing brain and how the rhythms contribute to brain development have not been well studied.

BDNF levels are low during the embryonic and/or early postnatal period and are enhanced with postnatal age in the majority of brain regions, whereas NT-3 levels are higher during the neonatal period as well as the embryonic period than in adulthood (11, 12). Generally, it is accepted that BDNF and NT-3 play their own important roles at specific periods and contribute to the development of brain structures and functions. Recently, on the other hand, it has been proposed that normal brain function and sleep generation are linked by common molecular systems and regulatory pathways (13). Thus, there is now a reevaluation of the importance of normal sleep rhythms for normal brain development, although the association between sleep rhythms and brain functions has been debated for a long time. The sleep-wake cycle is controlled by the external LD cycle via the SCN, a target region of the optic nerves (14, 15), which indicates the importance of a normal external LD cycle for brain development. However, the molecules associated with the external LD cycle (or the sleep-wake cycle) and their effects on brain development are largely unknown. Regarding BDNF, it has been reported that sleep deprivation increases BDNF mRNA levels in neonatal rat brain and that constant dark rearing during the neonatal period reduces BDNF mRNA in the visual cortex (16, 17). Here, we found evidence for diurnal variation in BDNF levels in a majority of brain regions from 14-day-old rats and an inverse variation of NT-3 levels specifically in the NCX as well as in the visual cortex (VCX). We then focused on the NCX of 14-day-old rats. We first examined the effects of an abnormal LD cycle or of a disturbed sleep-wake cycle on BDNF and NT-3 levels and on synaptophysin expression in the NCX of rat pups. An abnormal LD cycle and a disturbed sleep-wake cycle have influence on not only BDNF and NT-3 levels but also on other biologically active molecules. Therefore, we subsequently analyzed synaptophysin expression in the NCX using genetic mutants, Bdnf gene-deficient (BDNF-KO) mice, at 10 days of age to confirm whether abnormal levels of BDNF really affect structural development of the NCX. Finally, because sleep and circadian rhythm disruption is frequently observed in patients with psychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative diseases (13), we investigated alterations of the diurnal rhythms of BDNF and NT-3 levels and synaptophysin expression in mutant mice with abnormal sleep-wake cycles and compared them with controls. For the model mice, Ca2+-dependent activator protein for secretion 2 gene-deficient (CAPS2-KO) mice with an abnormal free-running rhythm and autistic-like phenotype were used at 14 days of age (18). In this work, we report that alteration of BDNF and NT-3 levels and/or perturbation in diurnal rhythms of their levels reduces synaptophysin-positive presynaptic terminals in layer IV of the NCX of juvenile rats.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Sprague-Dawley rats were raised in our laboratory and maintained on a 12-hour LD cycle (lights on at 07:00, lights off at 19:00) at a controlled ambient temperature (24 ± 1 °C). Male rat pups were used on postnatal day 14 except for experiments on age-related changes. Male BDNF-KO mice (19) and male CAPS2-KO mice with an abnormal free-running rhythm (18) were used on days 10 and 14, respectively. Food and water for mother rats were available ad libitum. All animal experiments were carried out according to the guidelines for animal experimentation of the Institute for Developmental Research, Aichi Human Service Center, and of the RIKEN Brain Science Institute.

Modification of the Rearing Environment

A single 8-h phase advance of the LD cycle was achieved using procedures similar to those previously reported for adult rats (8). The advance was started at 23:00 on postnatal day 6. Control and experimental pups were sacrificed at 10:30 on day 7 (groups A and C, respectively) or day 14 (groups B and D, respectively). Constant light rearing and dark rearing experiments were performed as follows: pups were reared for 27.5 h from 07:00 on the 13th postnatal day to 10:30 on the 14th day for the former rearing (group F) and for 23.5 h from 19:00 on the 13th postnatal day to 18:30 on the 14th day for the latter rearing (group G) (see Fig. 4B). Age-matched pups, which were reared under the regular cycle, were used as controls (groups B and E). Sleep deprivation was induced by 12-min shaking and 3-min resting during the light phase, from 07:00 on the 14th day (see Fig. 4C, Group H), and neuronal activity was reduced by a subcutaneous injection of urethane (500 mg/kg) into pups at 19:00 on the 13th day (see Fig. 4C, Group I). Control (group E) and experimental male pups (groups H and I) were sacrificed from 18:30 on the 14th day. All experiments were carried out with nursing mothers.

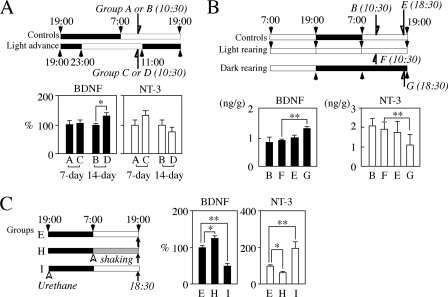

FIGURE 4.

Effects of the rearing environments on BDNF and/or NT-3 levels in the NCX. A, effects of an 8-h phase advance of the LD cycle. Rat pups were reared in the experimental conditions from 23:00 on the 6th day (upper panel). At 10:30 on the 7th and 14th days, the NCX was dissected from respective control pups (groups A and B) and respective phase-advanced pups (groups C and D). Values are mean ± S.E. of results from seven animals. Note the significant increase in BDNF levels 1 week after the phase advance (group D) and the slight increase and decrease in NT-3 levels on the 7th and 14th days, respectively. *, p < 0.05. B, effects of constant light or dark rearing. The NCX was dissected from controls (groups B and E) and experimental pups (groups F and G) at 10:30 or 18:30 on the 14th day (upper panel). Values are mean ± S.E. of results from eight animals except for group G (n = 5). Note significant differences in BDNF (closed columns) and NT-3 (open columns) levels between constant light (group F) and constant dark (group G) rearing groups. **, p < 0.01. C, effects of an abnormal sleep cycle. Pups were shaken to induce sleep deprivation from 07:00 on the 14th day (group H), or urethane was subcutaneously administered to pups at 19:00 on the 13th day (group I) (left panel). The NCX was dissected from pups at 18:30 on the 14th day. Values are mean ± S.E. of results from six animals for controls, five animals for the sleep deprivation experiment, and nine animals for the urethane injection experiment. Note the enhancement of BDNF levels and the reduction of NT-3 levels by sleep deprivation and the inverse effects of urethane on the two neurotrophins. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Dissection of Brain Regions

To examine diurnal changes in the levels of BDNF and NT-3, nine brain regions (Cbl; Hip; NCX (regions corresponding to the parietotemporal cortex); hypothalamus; VCX; superior colliculus; brain regions including the entorhinal cortex, piriform cortex, and amygdaloid nuclear complex; medial septum, and inferior colliculus) were dissected from 14-day-old control male rats at 4-h or 6-h intervals (see Figs. 2A or 5A). In other experiments, the Cbl, Hip, or NCX was dissected at zeitgeber times (ZTs) and at ages as depicted in the respective figures. All dissected brain regions were weighed immediately, frozen, and stored at −80 °C until use. To determine the relative amounts of active serine/threonine kinase Akt (Akt) and ERK1/2, the three brain regions (Cbl, Hip, and NCX) were dissected at 4-h intervals from 14-day-old rats.

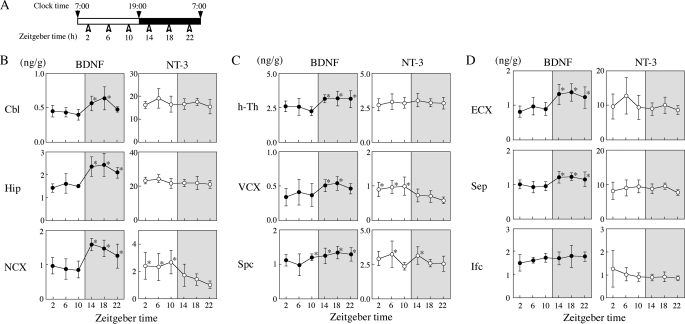

FIGURE 2.

Diurnal rhythms of BDNF and NT-3 levels in selected brain regions of juvenile rats. A, schedule for brain dissection. Nine brain regions from 14-day-old male pups were dissected every 4 h from ZT2 (09:00). B–D, diurnal variation in BDNF (●) and NT-3 (○). B, brain regions where, in adult rats, there is known molecular variation between sleeping and wakefulness. C, regions to which, in adult rats, the optic nerve projects. D, other regions. Values are mean ± S.D. of results from seven animals at each ZT. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with minimal levels in individual brain regions. Note diurnal alterations in BDNF in all brain regions except the inferior colliculus (Ifc) and those in NT-3 in the NCX, VCX, and superior colliculus (Spc). Also note high BDNF levels in eight brain regions and low NT-3 levels in the NCX and VCX during the dark phase. h-Th, hypothalamus; ECX, entorhinal cortex; Sep, medial septum.

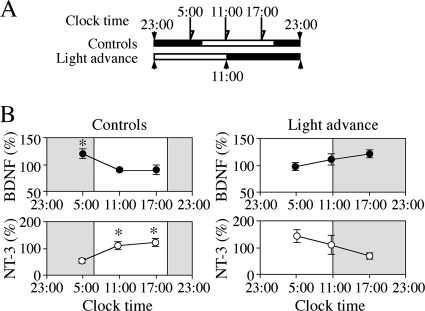

FIGURE 5.

Diurnal variations in levels of BDNF and NT-3 in the NCX of rats 1 week after the phase advance. A, schedule for brain dissection. B, diurnal variation in BDNF (●) and NT-3 (○) levels. Left panels, controls; right panels, phase-advanced pups. Values are mean ± S.E. of results from six to nine animals. Note the respective linear increase and decrease with clock time in levels of BDNF and NT-3 in the NCX of phase-advanced pups in contrast with fluctuating patterns in controls. *, p < 0.05 compared with the minimal level.

Extraction and Quantification of BDNF and NT-3

BDNF and NT-3 were extracted with a buffer containing 2 m guanidine hydrochloride and were quantified using two-site enzyme immunoassay systems that were established in our laboratory (12, 20). Briefly, standard neurotrophins or tissue extracts were incubated with polystyrene beads bearing immobilized neurotrophin-specific antibodies for 5 h at 30 °C, and the antigen-bound beads were further incubated with 1 milliunit of β-d-galactosidase-labeled Fab′ fragments at 4 °C for 16 h or more. The β-galactosidase activity bound to the beads was assayed using 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-galactoside as the substrate.

Analyses of Active Protein Kinases

Active Akt and ERK1/2 in the NCX were analyzed as described previously (8). Briefly, homogenates of the NCX were applied to 10% SDS gels. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunostained with the following antibodies: anti-phospho(Ser-473)-Akt, anti-Akt, anti-phospho(Thr-202 and Tyr-204)-ERK1/2, or anti-ERK1/2 (all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Beverly, MA), followed by peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit IgG prepared in our laboratory. Proteins were visualized with chemiluminescence reagents and quantified with an LAS-1000 (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Histological Analyses

For immunohistochemical staining of synaptophysin, phase-advanced 14-day-old rats (Group D in Fig. 4A) or CAPS2-KO mice were intracardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS after an initial perfusion with saline, whereas 10-day-old BDNF-KO mice were perfused with 30 mm HEPES buffer (pH 7.2) containing 2% paraformaldehyde, 0.5% glutaraldehyde, 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and 8% sucrose (19). Coronal paraffin sections of brains (7 μm) were prepared from brains of phase-advanced rat pups and BDNF-KO mice, and cryostat sections (10 μm) were prepared from brains of CAPS2-KO mice. Control sections were prepared from age-matched rat pups under regular conditions or age-matched WT mice. Paraffin sections were incubated with anti-synaptophysin antibodies (Progen Biotechnik GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) (1:1000), and cryostat sections were incubated with the same antibodies (1:3000) after passing through a graded alcohol series. Reactions were enhanced using ABC reagents (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) and visualized as described previously (19).

cDNAs for in situ hybridization were amplified using the following forward and reverse primers, respectively: for transcription factor Tbr1 (Tbr1), 5′-TAAGTGCAGGTCTCTCACTATG-3′ and 5′-TATTAACATCCCTACCATCCAT-3′, and for nuclear hormone receptor ROR (ROR), 5′-AGCGCCATTGTCCACTTT-3′ and 5′-CTGTGCCTCCCGATTACC-3′. The Tbr1 and ROR antisense riboprobes were prepared using their respective cDNAs as templates and were 3′ end-labeled with digoxigenin-dUTP (Roche). In situ hybridization brain histochemistry was performed as described previously (21), hybridizing cryostat sections (10 μm) with 0.2 μg/ml digoxigenin-labeled Tbr1 or ROR riboprobes.

Synaptophysin analyses were usually carried out using regions of the occipital and/or parietal cortices of littermate animals. The staining intensity was drawn using ImageJ, ver. 1.43r by scanning on stained sections corresponding to the occipital cortices of phase-advanced male pups and their control groups. The density of synaptophysin deposits in layers IV, V, and VI in the occipital and/or parietal cortices of individual animal groups was also measured according to the ImageJ ver. 1.43r program. Density in the white matter on the same section was subtracted as background. Numbers of synaptophysin-positive presynaptic terminals were quantified as described by Shinoda et al. (22).

Other Methods

Protein was quantified using a micro BCA protein assay reagent kit (Pierce) with BSA as the standard. All data were expressed as mean ± S.E. or S.D. Differences among groups were examined for statistical significance using analysis of variance (followed by a Fisher's protected least significant difference (PLSD) test) or the Student's t test.

RESULTS

Effects of Postnatal Age on Diurnal Rhythms of BDNF and NT-3 Levels in the Cbl, Hip, and NCX

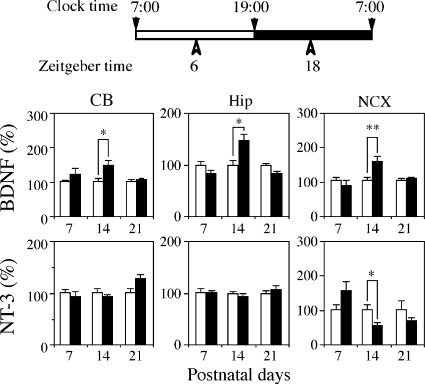

It has been reported that BDNF is abundant in adulthood, whereas NT-3 is abundant during the embryonic and/or early postnatal period (11, 12). We first explored developmental changes in the concentrations of BDNF and NT-3 in the rat Cbl, Hip, and NCX, where, in adult rats, there is a known molecular variation between sleeping and wakefulness (supplemental Fig. S1). In all three regions, BDNF levels sharply increased during the first 30 postnatal days. In contrast, NT-3 levels in the Cbl and NCX rapidly decreased after postnatal day 10, whereas the hippocampal level gradually increased with age up to 60 days of age. Levels of BDNF and NT-3 in the Cbl and NCX crossed at around 2 weeks of age. In the next step, to investigate whether diurnal rhythms in BDNF and NT-3 concentrations were age-dependent, the concentrations of BDNF and NT-3 in the Cbl, Hip, and NCX of male pups at 7, 14, and 21 days of age were measured at ZT6 and ZT18 (Fig. 1). When the levels at ZT6 were normalized to 100% at any age, BDNF levels at ZT18 significantly increased in the three brain regions of 14-day-old rats but not 7- or 21-day-old rats, (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 by the Student's t test). Regarding NT-3 concentrations, a prominent, statistically significant reduction at ZT18 was found in the NCX of 14-day-old rats (*, p < 0.05). A slight reduction in NT-3 levels at ZT18 was also observed in the NCX of rats at 21 days of age, whereas, at 7 days of age, a slight increase was observed, although they did not reach statistical significance. On the other hand, there were no significant differences in NT-3 levels in the Cbl and Hip for any ages between the two ZTs.

FIGURE 1.

Age-dependent diurnal rhythms of BDNF and NT-3 levels in the Cbl, Hip, and NCX. Three brain regions were dissected from 7-, 14-, and 21-day-old male rat pups at ZT6 (open columns) and ZT18 (closed columns). Values are mean ± S.E. of results from six animals. Note the prominent statistically significant differences between ZT6 and ZT18 in 14-day-old rats. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 by the Student's t test.

Diurnal Rhythms in BDNF and NT-3 Levels in Selected Brain Regions of Juvenile Rats

It has been reported that circadian variations in BDNF levels are observed in limited brain regions of adult rats (3, 6–8). Because increases in BDNF concentrations in the dark phase were prominent in the Cbl, Hip, and NCX of rats at 14 days of age (see Fig. 1), we examined changes with ZT in BDNF and NT-3 levels in nine rat brain regions at 14 days of age according to the schedule of Fig. 2A. As shown in Fig. 2B, there were clear diurnal variations in BDNF concentrations, with high levels during the dark phase and low levels during the light phase, in the Cbl (F(5,36) = 6.399, p < 0.001), Hip (F = 11.25, p < 0.001) and NCX (F = 10.94, p < 0.001). Similar variations were also found in the hypothalamus (F = 4.745, p = 0.002), VCX (F = 2.814, p = 0.0303), and superior colliculus (F = 3.148, p = 0.0185) (regions to which the optic nerve projects in adult rats, see Fig. 2C) and in the entorhinal cortex (F = 6.865, p < 0.001) and medial septum (F = 4.786, p = 0.0029), except the inferior colliculus (F = 0.986, p = 0.442) (other regions, see D). When compared with the minimal levels observed in each region, statistically significant increases were found in BDNF levels during the dark phase in eight brain regions except for the inferior colliculus (*, p < 0.05 by the Fisher's PLSD). On the other hand, NT-3 levels varied only in specific cortical regions such as the NCX (F(5,36) = 5.215, p = 0.0011) and VCX (F = 6.050, p = 0.0004), with an inverse cycle compared with BDNF, high in the light phase and low in the dark phase (see Fig. 2, B and C). Differences in NT-3 levels between the minimal level (ZT22) and ZT2 or ZT6 or ZT10 were statistically significant in both NCX and VCX (*, p < 0.05). There were no clear variations in NT-3 levels in other regions examined here (see Fig. 2, B–D). The BDNF/NT-3 balance in the NCX and VCX also oscillated with a pattern similar to the BDNF level but with larger amplitude (F(5,36) = 6.007, p = 0.0004 for the NCX; F = 7.026, p = 0.0001 for the VCX).

Diurnal Rhythms in Active Akt and ERK in the NCX

BDNF is synthesized in an activity-dependent manner (1). There are several intracellular signals and transcription factors that are known to stimulate BDNF production. Our previous report demonstrated in vivo regulation by p38 MAPK of AMPA-induced BDNF production in adult rat Hip (23). In preliminary experiments, however, there were no diurnal rhythms of p38 MAPK in any regions of the Cbl, Hip, and NCX of rats at 14 days of age. We investigated changes with ZT in amounts of active Akt and ERK1/2 in the three brain regions of 14-day-old rats. In the NCX, both amounts of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated Akt proteins oscillated with their own cycles (Fig. 3A). Relative amounts of active Akt were markedly low in the dark phase in contrast to high BDNF levels (Fig. 3B, F(5,12) = 3.347, p = 0.040; *, p < 0.05, statistical significances compared with minimal level at ZT22), whereas amounts of active Akt were also reduced around ZT14 and ZT18 (Fig. 3C, F(5,12) = 5.504, p = 0.0073; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, compared with minimal level at ZT14). In the Hip and Cbl, compared with small diurnal changes in total Akt levels, active Akt levels were prominently high during the light phase, resulting in high relative amounts of active Akt in the light phase (supplemental Fig. S2, A and B). A high level of BDNF mRNA during the light phase was observed in the Hip. On the other hand, relative amounts of active ERK1 and ERK2 in the NCX of 14-day-old rats were inclined to increase at the end of the dark phase, in contrast with NT-3 levels (Fig. 3, D and E, F(5,12) = 4.734, p = 0.013 for ERK1; *, p < 0.05 between ZT14 (minimal level) and ZT18 or ZT 22 by the Fisher's PLSD; F = 2.333, p = 0.106 for ERK2). However, they did not show any variations with ZT in the Hip and Cbl as is the case for the NT-3 level (supplemental Fig. S2, A and B). The following experiments were focused on the NCX of 14-day-old rats because diurnal variations in both BDNF and NT-3 levels (also active Akt and ERK1/2 levels) were limited to the NCX.

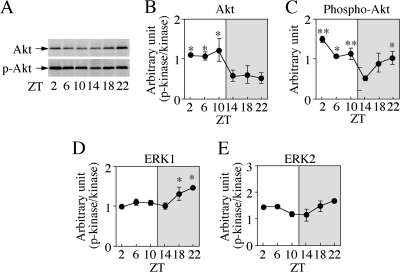

FIGURE 3.

Diurnal rhythms of Akt and ERK1/2 in the NCX of juvenile rats. Male rat pups were sacrificed at 14 days of age with the schedule indicated in Fig. 2A. A quantitative assessment was performed by the determination of chemiluminescence intensity of objective proteins after staining immunoblots with each specific antibody. A–C, diurnal changes in Akt. A, Western blot analysis. Note own diurnal variations in both total and active Akt protein. B and C, changes in relative amounts (B) and amounts (C) of active Akt. Values are mean ± S.E. of results from three animals. Note the significant reduction in active Akt levels in the dark phase. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with the minimal value. D and E, diurnal changes in ERK1/2, which are shown by relative amounts of active ERK1 (D) and active ERK2 (E). Values are mean ± S.E. of results from three animals. Note the significant increase in the relative amounts of active ERK1 between ZT14 and ZT18 or ZT22. Compared with Akt, diurnal variation was not very pronounced. *, p < 0.05.

Recently, it has been reported that cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and/or methyl CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) regulate activity-dependent BDNF production in the NCX (24, 25). Then we investigated relative amounts of active CREB and three types of active MeCP2 in the NCX of 14-day-old rats. Although relative amounts of active CREB were slightly high at the beginning of the light phase compared with those at ZT22, diurnal variation was not prominent (supplemental Fig. S2C-i). Although considerable levels of total MeCP2 and phospho(Ser-80)-MeCP2, being phosphorylated in resting neurons (26), were found in the NCX of 14-day-old rat pups as well as adult rats, their diurnal variations in pups were not obvious (supplemental Fig. S2, C-ii and C-iii). On the other hand, signals corresponding to around 75 kDa of phospho(Ser-421)-MeCP2, being phosphorylated in active neurons (25), were clearly observed in the adult NCX but hardly in the juvenile NCX (supplemental Fig. S2C-ii). This was also true of phospho(Ser-292)-MeCP2. Signals of phospho(Ser-421 or Ser-292)-MeCP2 at a younger age were too weak to determine.

Environmental Effects on Diurnal Rhythms of BDNF and NT-3 levels in the NCX

It has been reported that, in specific brain regions of adult rats, an 8-h phase advance of the LD cycle causes an increase or decrease in BDNF concentrations after a 12-h rearing or a 1-week rearing, respectively (8). Therefore, we carried out similar experiments using juvenile rats (Fig. 4A, upper panel). The experiment was started at 23:00 on the 6th postnatal day when the pups were still together with their mothers. In the NCX 12 h after the phase advance (Fig. 4A, lower panel, 7-day), mean relative concentration of BDNF in phase-advanced pups (group C) differed little from that in controls (group A), whereas that of NT-3 in the former group was increased slightly but not significantly. The mean relative BDNF level 1 week after the phase advance (group D) was significantly elevated compared with that of age-matched controls (group B), whereas the NT-3 level was conversely reduced, although this did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4A, 14-day; *, p < 0.05 for BDNF by the Student's t test). The BDNF/NT-3 balance in the NCX of phase-advanced rats at 14 days of age was higher than that of controls (mean ± S.E. (n = 7); 0.230 ± 0.035 for controls; 0.516 ± 0.111 for the phase-advanced group, p = 0.020).

We next investigated which factors might cause the significant increase in BDNF level in the NCX. First, we examined whether constant light or dark rearing influenced BDNF and NT-3 levels in the NCX (Fig. 4B). The light rearing was carried out for 27.5 h from 07:00 on the 13th day until 10:30 on the next day (group F), and the dark rearing was for 23.5 h from 19:00 on the 13th day until 18:30 on the next day (group G) (Fig. 4B, upper panel). No remarkable alteration in mean BDNF level by light rearing was found in the NCX (Fig. 4B, lower panel, closed columns, groups B and F). On the other hand, the dark rearing significantly enhanced mean BDNF level (**, p < 0.01, differences between groups G and F or E by the Fisher's PLSD). Similar inverse alterations in mean NT-3 levels compared with BDNF were observed (Fig. 4B, open columns). Differences in mean levels of NT-3 between light and dark rearing groups were also statistically significant (**, p < 0.01 between groups G and F; also p < 0.05 between groups G and E). Second, to examine whether the sleep-wake cycle affects neurotrophin levels, the experiments were carried out according to the protocols depicted in Fig. 4C (left panel). Sleep deprivation (group H) significantly increased and decreased levels of BDNF and NT-3, respectively, in the NCX of 14-day-old rats (right panel, closed columns for BDNF and open columns for NT-3, *, p < 0.05 between groups E and H). In contrast, urethane, an anesthetic drug, had inverse effects on the respective neurotrophins in the NCX (Fig. 4C, **, p < 0.01 between groups E and I).

It has been reported that in adult rats, the circadian rhythm of body temperature is disturbed even 7 days, as well as 1 day, after a single 8-hour advance of the LD cycle (27). Therefore, we examined the diurnal variations in BDNF or NT-3 levels in the NCX of pups 7 days after the phase advance. The NCX was dissected from phase-advanced pups and controls at clock times depicted in Fig. 5A. In the control groups, BDNF and NT-3 levels in the NCX fluctuated in similar cycles as those in Fig. 2B (Fig. 5B, left panel; F(2,24) = 4.494, p = 0.0220 for BDNF; F = 6.627, p = 0.0056 for NT-3; *, p < 0.05 compared with minimal level). On the other hand, in the NCX of phase-advanced groups, BDNF and NT-3 levels in the dark phase were relatively higher and lower, respectively, compared with those in the light phase (Fig. 5B, right panels, p < 0.05 between 5:00 and 17:00 by the Student's t test for BDNF or NT-3 levels). However, their levels were linearly increased or decreased with clock time, different from diurnal changes in controls (F(2,15) = 2.232, p = 0.141 for BDNF; F(2,18) = 3.421, p = 0.0551 for NT-3). The BDNF/NT-3 balance in the NCX of phase-advanced pups were also linearly increased with clock time (F(2,15) = 3.883, p = 0.0438, p < 0.05 between 5:00 and 17:00 by the Fisher's PLSD).

Effects of Phase Advance of the LD Cycles on Synaptophysin Expression in the NCX

In the NCX of 14-day-old rats under regular conditions, strong immunoreactivities of BDNF and NT-3 were found in cells in layers V-VI and layer V, respectively (supplemental Figs. S3 and S4, B and F), indicating that their distribution was fairly layer-specific. On the other hand, in the NCX of phase-advanced pups, cells with strong BDNF immunoreactivities were found not only in layers V-VI but also in layers II-III, indicating alterations in BDNF levels in layers II-III by the phase advance (supplemental Fig. S4, C, E, and G). To investigate effects of alterations in levels of these layer-specific proteins induced by abnormal LD cycle on cortical development, we examined the expression of synaptophysin in the NCX of 14-day-old rats that received the phase advance of the LD cycle for 1 week from the 6th day (group D in Fig. 4A) in comparison with age-matched controls (group B). In both groups, synaptophysin was widely distributed throughout the NCX (Fig. 6A, i and ii). In the control group B, there was a relatively strong staining layer, corresponding to layer IV of the NCX, referring to cresyl violet staining (see Fig. 6A, iii and iv). In contrast, the intensity of synaptophysin staining in the NCX from pups of experimental group D did not differ greatly among the layers (Fig. 6Av). Fig. 6Avi also shows granular deposition of synaptophysin in the extracellular space in layer IV of the NCX from control pups, this being much less pronounced in experimental pups (Fig. 6Avii). Then we quantified the intensity of synaptophysin staining and numbers of presynaptic terminals (Fig. 6B). The scanning of stained sections from layers I to VI of the NCX showed high synaptophysin expression around layer IV compared with other layers in both groups. However, obviously, synaptophysin deposition in layer IV was denser in control group B than in experimental group D (Fig. 6Bi). Quantification analyses demonstrated that mean synaptophysin density in cortical layer IV (also layer V) was significantly higher in group B than in group D, whereas there was no difference in the density of layer VI between the two groups (Fig. 6Bii, F(5,57) = 55.72, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01 between groups B and D for either layer IV (or V)). This was also the case for numbers of synaptophysin-positive presynaptic terminals per area in layers IV and V-VI (Fig. 6Biii, F(3,39) = 47.21, p < 0.001). A prominent decrease of about 20% in numbers of presynaptic terminals per area in cortical layer IV was found in group D compared with group B (**, p < 0.01).

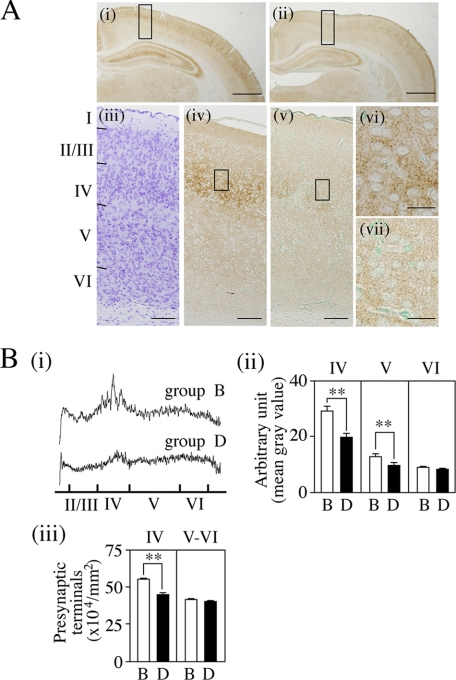

FIGURE 6.

Effects of an 8-h phase advance of the LD cycle on synaptophysin expression in the NCX. A, immunohistochemical staining of synaptophysin. Male rat pups were reared in the experimental conditions from 23:00 on the 6th day as indicated in Fig. 4A. At 10:30 on the 14th day, control pups (group B) and phase-advanced pups (group D) were fixed. i and ii, synaptophysin staining in brains. Note that the pigment deposition was relatively prominent in cortical layer IV and in the molecular layer of granule neurons and the stratum radiatum of the CA3 region of the Hip in group B (i), whereas the staining intensity in group D was weak in all regions except for the stratum radiatum (ii). iii, cresyl violet staining. iv–vii, synaptophysin staining. iv and v, the cortical areas boxed in i and ii, respectively. Note strong and moderate pigment deposition in cortical layer IV in control group B (iv) and experimental group D (v), respectively. vi and vii, high magnification of the boxed areas of (iv) and (v), respectively. Note that granular pigmentation was much more prominent in the extracellular spaces in layer IV in group B (vi) compared with group D (vii). Scale bars = 1 mm in i and ii; 100 μm in iii–v; 20 μm in vi–vii. B, quantitative analyses of synaptophysin staining intensity and synaptophysin-positive presynaptic terminals. i and ii, synaptophysin density. Synaptophysin density on stained sections was quantified according to the ImageJ, ver. 1.43r program. Background, the density in the white matter on the same sections, was subtracted from measured values. i, scanning patterns of cortical layers. Note that the density of synaptophysin in layer IV is relatively higher than those in other layers in both animals, and it is denser in control pups (group B) than in phase-advanced pups (group D). ii, Mean density in layers IV-VI. Values are mean ± S.E. of nine determinations for group B (open columns) or 13 determinations for group D (closed columns) in nine sections from three animals. Note that the density in layers IV and V, but not in layer VI, is significantly reduced in group D to about 68 and 75%, respectively, of group B (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001). iii, numbers of synaptophysin-positive presynaptic terminals. Numbers of presynaptic terminals in 100 μm2 (8 areas/section) were counted, and their average was defined to one determination as described previously (22). Values are mean ± S.E. of nine determinations for group B or 16 determinations for group D in nine sections from three animals. Note that the mean number of presynaptic terminals in layer IV in group D is about 80% that of controls (**, p < 0.01).

Effects of Bdnf Gene Deficiency

Fig. 4A shows that the phase advance affects BDNF or NT-3 levels or the BDNF/NT-3 balance. To investigate whether an alteration in BDNF levels is really associated with low synaptophysin levels, we stained the NCX of 10-day-old BDNF-KO mice with anti-synaptophysin antibodies for comparison with age-matched WT and heterozygous mice (Fig. 7A). Differences in synaptophysin staining intensity among the layers of the NCX were clear in the latter two groups but less so in BDNF-KO mice (Fig. 7A, ii, iii, and iv). With reference to cresyl violet staining (Fig. 7Ai), relatively strong staining for synaptophysin in WT mice was evident in layer IV and part of layer V of the NCX, with the intensity also being stronger than in the same layers of homozygous mice (Fig. 7A, ii and iv or v and vi). This was also true of heterozygous mice (Fig. 7Aiii). Fig. 7B shows semiquantitative results of synaptophysin staining intensity and synaptophysin-positive presynaptic terminals. Density of synaptophysin deposition in cortical layers IV and V, but not in layer VI, was as follows (most dense to least dense): WT, heterozygous and BDNF-KO mice (Fig. 7Bi, F(8,54) = 18.16, p < 0.001). Differences between BDNF-KO and WT or heterozygous mice were statistically significant in the two layers, IV and V, whereas that between WT and heterozygous mice was limited to layer IV (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). Synaptophysin-positive presynaptic terminals per area of WT mice in cortical layer IV, but not in layers V-VI, also was greater in number compared with those of other types of mice (Fig. 7Bii, F(5,30) = 15.87, p < 0.001). In BDNF-KO mice and their heterozygous counterparts, they were reduced to about 67 and 88%, respectively, in comparison with WT mice (**, p < 0.01 between WT and heterozygous or BDNF-KO mice).

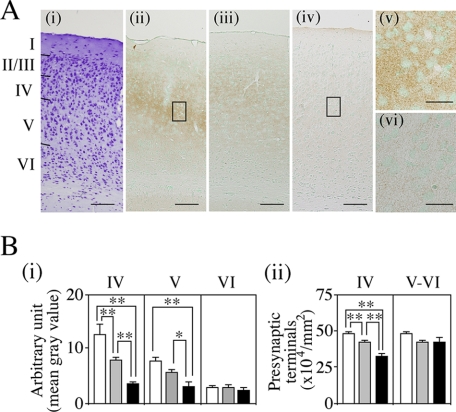

FIGURE 7.

Effects of Bdnf gene deficiency on synaptophysin expression in the NCX. A, immunohistochemical staining of synaptophysin. Brain sections were prepared from BDNF-KO, WT, and heterozygous mice at 10 days of age. i, cresyl violet staining. ii–iv, synaptophysin staining. Note the decreases in synaptophysin expression in layers IV and V in heterozygotes (iii) and BDNF-KO mice (iv) compared with WT mice (ii). v and vi, high magnification of the boxed areas in WT (ii) or in BDNF-KO (iv) mice, respectively. Note the decrease in extracellular and granular synaptophysin deposition in BDNF-KO mice (vi) in comparison with WT mice (v). Scale bars = 100 μm in i–iv, 20 μm in v and vi. B, quantitative analyses of synaptophysin staining intensity and synaptophysin-positive presynaptic terminals. Quantification methods were as in Fig. 6B. i, mean density in layers IV-VI. Values are mean ± S.E. of seven determinations in six sections from two WT (open columns), heterozygous (gray columns), and BDNF-KO (closed columns) mice. Note that the density in layer IV is significantly reduced in order of heterozygotes (63%) and homozygotes (29%) (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). A similar, although slightly smaller, reduction was also seen in layer V but not in layer VI (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). ii, numbers of synaptophysin-positive presynaptic terminals. Values are mean ± S.E. of nine determinations in six sections from two mice for layer IV and four determinations for layers V-VI. Note that the mean numbers of presynaptic terminals in layer IV in heterozygotes and homozygotes are about 88 and 67%, respectively, of those in WT mice (**, p < 0.01).

Effects of CAPS2 Gene Deficiency

The present results suggest that an abnormal LD cycle and/or abnormal sleep-wake cycle disturb diurnal rhythms of BDNF and/or NT-3, resulting in the reduction of synaptophysin expression. First, we examined whether there is a disturbance in the diurnal rhythms of BDNF and NT-3 levels in CAPS2-KO mice because they have been reported to exhibit an abnormal free-running rhythm (18). BDNF and NT-3 levels in the NCX of 14-day-old CAPS2-KO mice and their heterozygous counterparts were determined at ZT 6 and ZT22 (Fig. 8Ai). There was no significant difference in the mean levels of BDNF at ZT6 between CAPS2-KO and control mice. At ZT22, the BDNF level in heterozygotes tended to increase, whereas it remained unchanged in mutant mice, resulting in a statistically significant difference between the two types of mice at ZT22 (Fig. 8Aii, closed columns; *, p < 0.05 by the Student's t test). On the other hand, mean levels of NT-3 at ZT22 were slightly lower in CAPS2-KO or heterozygous mice compared with their respective levels at ZT6, whereas NT-3 levels in mutant mice were slightly higher than control levels at both ZT6 and ZT22 (Fig. 8Aii, open columns), although any reduction or enhancement did not reach statistical significance. The BDNF/NT-3 balance at ZT22 were significantly reduced in CAPS2-KO mice compared with the heterozygous case (mean ± S.E.; 1.665 ± 0.203, n = 5 for heterozygotes; 1.002 ± 0.083, n = 7 for CAPS2-KO mice, p = 0.0068).

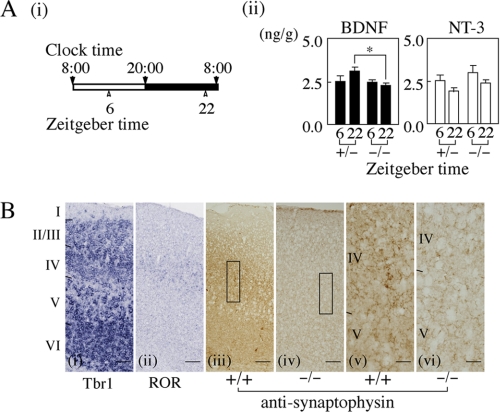

FIGURE 8.

Effects of Caps2 gene deficiency on the diurnal rhythm of BDNF or NT-3 and synaptophysin expression in the NCX. A, effects on diurnal variation in BDNF and NT-3 levels. i, schedule for brain dissection. The NCX was dissected from 14-day-old CAPS2-KO mice (−/−) and their heterozygotes (+/−) at ZT6 and at ZT22. ii, BDNF (closed columns) and NT-3 (open columns) levels. Values are mean ± S.E. of results from five to seven animals. Note the lack of diurnal variation in BDNF levels in CAPS2-KO mice and the statistically significant difference in BDNF levels at ZT22 between homozygous and heterozygous mice (*, p < 0.05). B, immunohistochemical staining of synaptophysin. Brain sections were prepared from CAPS2-KO and WT mice at 14 days of age. i and ii, in situ hybridization of Tbr1 (i) and ROR (ii), respectively. Neurons in layers III, V, and VI express Tbr1, whereas those in layer IV express ROR. iii–vi, synaptophysin staining. iii and iv, cortical layers in WT (iii) and CAPS2-KO (iv) mice. Note that synaptophysin was widely distributed in the cortical layers of WT mice and expressed strongly and extensively in layer IV of WT mice but only weakly in that of CAPS2-KO mice. v and vi, high magnification of the boxes in iii and iv, respectively. Note that synaptophysin signals were more prevalent in the extracellular spaces of cortical layer IV from WT mice (v) compared with those from CAPS2-KO mice (vi). Scale bars = 100 μm in i–iv; 25 μm in v and vi.

In CAPS2-KO mice, the number of Tbr1-positive cells in cortical layer V was higher than that in the same layer of WT (mean ± S.E. (%), 100.7 ± 3.7 (n = 20) for controls; 130.9 ± 7.3 (n = 21) for CAPS2-KO, p < 0.01), indicating the presence of an abnormal layer structure. Next, we examined alterations in synaptophysin expression in the NCX of mutant mice with no diurnal rhythm of BDNF levels. Fig. 8B illustrates in situ hybridization of the cortical layer markers, Tbr1 (i) and ROR (ii), and immunohistochemistry for synaptophysin (iii–vi) in the NCX of 14-day-old WT and CAPS2-KO mice. In line with the specific locations of Tbr1 in layers III and V-VI and of ROR in layer IV, granular pigment deposition of synaptophysin was relatively strong in cortical layer IV of WT mice, especially in the area corresponding to the neurophil (Fig. 8B, iii and v). On the other hand, in CAPS2-KO mice, there was little difference in staining intensity among the layers, and only weak granular pigment deposition was observed (Fig. 8B, iv and vi). Semiquantitative analyses demonstrated that, in cortical layer IV of CAPS2-KO mice, synaptophysin density was about 33% of that in WT mice (p < 0.01), and the number of synaptophysin-positive presynaptic terminals per area was reduced to about 78% (mean ± S.E. (terminals/mm2 × 10−4); 48.3 ± 1.1 (n = 9) for WT; 37.5 ± 1.1 (n = 9) for CAPS2-KO, p < 0.01). In contrast, there was no difference in numbers of terminals in layers V-VI between the two types of mice (42.4 ± 0.6 (n = 4) for the former; 41.2 ± 0.9 (n = 4) for the latter, p = 0.298).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that diurnal variations in BDNF concentration, high in the dark phase and low in the light phase, are age-dependently acquired in specific brain regions. This is in line with a previous finding that a single 8-h phase advance of the LD cycle affects BDNF production in several brain regions of rat pups after 7 postnatal days of age (8). On the other hand, diurnal variations in NT-3 levels were also obvious in limited regions of rats after 7 postnatal days of age, such as the NCX and VCX, although this cycle was inverse compared with BDNF. For both BDNF and NT-3, it should be noted that diurnal variations were prominent in pups around 14 days of age, the period when the pups' eyes open and the age at which the BDNF/NT-3 balance in the NCX and VCX oscillates with much larger amplitude compared with BDNF itself. Our previous report has shown that, in adult rats, the BDNF level in the NCX is minimal at ZT14, around the time when it begins to increase in juvenile rats (8). This indicates that, in the NCX of adult rats, neurons are active even in the sleeping phase because BDNF is synthesized in an activity-dependent manner. The findings are consistent with an electrophysiological observation that the human adult visual cortex is still active during the sleeping phase, possibly performing rearrangement of memories (28). On the other hand, an oscillating pattern of BDNF in the NCX (also in other brain regions) of 14-day-old rats was much simpler than the pattern in adulthood, and this simple oscillation in BDNF (and/or NT-3) appears to play important roles in the cortical development of juvenile rats as discussed below.

It is well known that BDNF is synthesized in an activity-dependent manner (1). Inverse changes of BDNF and NT-3 are also observed in kainic acid-injected rat Hip and in external light-exposed SCN. In these cases, glutamatergic neurons are activated (4, 5, 20). We have reported that in adult rats, activation of glutamatergic neurons by AMPA enhances relative amounts of phospho-p38 MAPK in the Hip, and the external light input activates CREB in the visual cortex, resulting in BDNF enhancement (8, 23). Activation of p38 MAPK does not appear to be involved in BDNF synthesis in the juvenile rat NCX because of no diurnal rhythms in a preliminary experiment. In general, it has been shown that activity-dependent phosphorylation of CREB or MeCP2 is increased with postnatal age and that the phospho(Ser-421)-MeCP2 effect on BDNF synthesis has been observed in the NCX of rats after 19 days of age (24, 25). Given no circadian rhythm of active CREB or little amounts of phospho(Ser-471)-MeCP2 in 14-day-old rat NCX, these transcription factors are hardly considered to be main factors of BDNF synthesis at this age in contrast to adult cases. Recently, it has been reported that in cortical cultures, NMDA receptors are involved in neurotrophin-regulated BDNF synthesis and that activity-dependent glutamate release stimulates Akt phosphorylation through the NMDA-PI3K pathway, which is not blocked by anti-BDNF receptor (TrkB) antibody (29, 30). Thus, it appears possible that Akt is involved in processes of BDNF production. If this is the case for juvenile rat brains, active Akt levels will fluctuate in an inverse cycle compared with BDNF protein levels because BDNF protein levels are enhanced around 12 h after the phase advance of the LD cycle in adult rat VCX (8). Inverse cycles are evident in juvenile rat Cbl, Hip, and NCX, suggesting a possible Akt-BDNF pathway. Similarly, there may be a possible association between active ERK1 and NT-3 in the juvenile rat NCX, given that active ERK 1 levels fluctuate in an inverse cycle compared with NT-3 protein levels. On the other hand, BDNF possibly regulates diurnal rhythms of active ERK1/2 levels because exogenous BDNF is well known to activate ERK1/2 via the TrkB receptor in cortical cultures. In that case, active ERK1 levels will fluctuate in a similar cycle to BDNF protein levels. This could be the case for the juvenile rat NCX. Similarly, NT-3 may conceivably be able to regulate diurnal rhythms of active Akt levels. However, these regulations are unlikely in the Hip and Cbl because there are no diurnal rhythms of active ERK1 levels or NT-3 levels, whereas the rhythms of BDNF and active Akt levels are prominent. Thus, the regulation of these rhythms by BDNF or NT-3 is hardly considered.

It has been reported that both BDNF and NT-3 regulate the dendritic growth of pyramidal neurons in specific layers of the developing cerebral cortex after birth (31, 32). Moreover, BDNF and NT-3 are also shown to oppose one another in regulating the dendritic growth of pyramidal neurons in specific layers. Namely, BDNF causes striking growth of basal and apical dendrites in layer IV, whereas NT-3 completely prevents BDNF-induced dendritic growth in this layer (33–36). This indicates that the BDNF/NT-3 balance (or the diurnal variation of its balance) is critical for dendritic growth in respective cortical layers. In this study, we showed that BDNF and NT-3 levels (or the BDNF/NT-3 balance) in the NCX of phase-advanced juvenile rats linearly altered with ZTs, obviously different from fluctuation patterns of control rats, indicating a perturbation in diurnal rhythms of BDNF or NT-3 levels (or the BDNF/NT-3 balance). On the other hand, there was no diurnal variation in the BDNF/NT-3 balance in the NCX of CAPS-KO mice. The balance remained low in the dark phase, whereas it was usually high in the dark phase. Moreover, the present results also show that, in the NCX of rats or mice with abnormal rhythms of the BDNF/NT-3 balance, synaptophysin expression and numbers of synaptophysin-positive presynaptic terminals are markedly reduced. Reportedly, BDNF increases synapse density in the dendrites of developing cortical neurons, and synaptophysin reaches a maximum level at an early postnatal age (37, 38). In the rat infralimbic cortex, a cortical region receiving a strong afferent input from the SCN, the diurnal rhythm has been suggested to regulate the dendritic architecture and spine density of pyramidal neurons (39). Thus it should be noteworthy that a perturbation in the diurnal rhythms of the BDNF/NT-3 balance in the NCX of juvenile rodents induced by abnormal LD cycle or genetic manipulation largely impairs dendritic growth in the developing rodent cortex. A similar reduction of synaptophysin expression in juvenile BDNF-KO mice indicates that BDNF protein really contributes to synaptophysin expression. Experiments using heterozygotes also show that appropriate levels of BDNF are necessary for normal expression of synaptophysin.

Reduction of synaptophysin expression by the phase advance of the LD cycle is restricted to layer IV and a part of layer V of the NCX from 14-day-old rats. Reportedly, cortically expressed BDNF can support the maintenance of dendrite structure in the NCX, and BDNF mRNA-expressing cells are observed in layers II-III and VI (40–43). Generally, BDNF is known to be anterogradely transported in the CNS, and, in the NCX, projections to layer IV from layers II-III are well documented (44). In adult rats, an external light dependence of BDNF production has already been demonstrated in cells of layers II-III in the VCX (8). This study also shows that there are cells with strong signals of BDNF protein in layers II-III of the NCX from phase-advanced juvenile rats, although they were limited to cells around layers V-VI in regular conditions (supplemental Fig. S4). An increase in the numbers of cells strongly expressing BDNF in layers II-III of the NCX from phase-advanced pups might influence the BDNF/NT-3 balance, which contributes to reduction of synaptophysin expression in layer IV.

Constant light and dark rearing experiments show that BDNF or NT-3 levels in the NCX of 14-day-old rats are controlled by the external LD cycle. In addition, it is also evident that perturbation in the sleep-wake cycle induces alterations in BDNF and NT-3 levels. Sleep deprivation causes an increase in BDNF levels and a decrease in NT-3 levels. Thus BDNF and/or NT-3 expression in the juvenile rat NCX is influenced by the sleep-wake cycle as well as the external LD cycle. Regarding the findings related to BDNF and sleep, it has been reported that intraventricular injection of exogenous BDNF enhances spontaneous sleep in adult rabbits (45), whereas BDNF release is reduced in the NCX of CAPS2-KO mice with an abnormal free-running rhythm (18). On the other hand, it has been reported that lesions of the SCN, a target region of optic nerves, cause loss of the circadian rhythm in sleep-wakefulness (14, 15, 46), indicating regulation of the rhythm by the LD cycle. Regulation of BDNF or NT-3 levels by the sleep-wakefulness rhythm through the LD cycle and regulation of the sleep-wake cycle by the fluctuation of BDNF levels may both be considered.

An abnormal sleep-wake cycle is often observed in patients with neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, and disturbance in intracortical connectivity is suggested in autistic patients (13, 47, 48). Generally, BDNF is a candidate neurotrophic factor linked with the etiology of neurodevelopmental disorders (49). It has been shown that CAPS2-KO mice not only generate an abnormal free-running rhythm but also develop autistic-like behaviors (18, 21). It was evident from the present study that there is no diurnal rhythm of BDNF levels (or abnormal BDNF/NT-3 balance) in the NCX of mutant mice. Thus, Caps2 gene deficiency-induced perturbation in diurnal rhythms of BDNF levels (or the BDNF/NT-3 balance) likely contributes to abnormal sleep-wake cycles and/or autistic-like behaviors. It has been previously reported that diurnal rhythms of BDNF levels are found in the serum of normal adult human and rat controls, and in rats, there is a good correlation between diurnal rhythms of BDNF in serum and the NCX (50). However, further investigations are necessary to evaluate the relationship between autism and the circadian rhythms of biologically active molecules such as BDNF and/or NT-3.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yo Shinoda at the RIKEN Brain Science Institute (Wako, Japan) for instruction on the counting method for presynaptic terminals and Dr. Ayako Taguchi at the Institute for Developmental Research, Aichi Human Service Center (Kasugai, Japan), for help with histological sample preparation.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- BDNF

- brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- NT-3

- neurotrophin-3

- LD

- light-dark

- Cbl

- cerebellum

- Hip

- hippocampus

- NCX

- neocortex

- SCN

- suprachiasmatic nucleus

- VCX

- visual cortex

- BDNF-KO

- Bdnf gene-deficient

- CAPS2-KO

- Ca2+-dependent activator protein for secretion 2 gene-deficient

- ZT

- zeitgeber time

- Tbr1

- transcription factor Tbr1

- ROR

- nuclear hormone receptor ROR

- PLSD

- protected least significant difference

- CREB

- cAMP response element-binding protein

- MeCP2

- methyl CpG binding protein 2.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lindsay R. M. (1993) Neurotrophic Factors, pp. 257–277, Academic Press, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 2. Croll S. D., Ip N. Y., Lindsay R. M., Wiegand S. J. (1998) Brain Res. 812, 200–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bova R., Micheli M. R., Qualadrucci P., Zucconi G. G. (1998) Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 57, 321–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Earnest D. J., Liang F. Q., Ratcliff M., Cassone V. M. (1999) Science 283, 693–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liang F. Q., Allen G., Earnest D. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 2978–2987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schaaf M. J., Duurland R., de Kloet E. R., Vreugdenhil E. (2000) Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 75, 342–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dolci C., Montaruli A., Roveda E., Barajon I., Vizzotto L., Grassi Zucconi G., Carandente F. (2003) Brain Res. 994, 67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Katoh-Semba R., Tsuzuki M., Miyazaki N., Matsuda M., Nakagawa C., Ichisaka S., Sudo K., Kitajima S., Hamatake M., Hata Y., Nagata K. (2008) J. Neurochem. 106, 2131–2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cho K. (2001) Nat. Neurosci. 4, 567–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gonzalez M. M., Aston-Jones G. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4898–4903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaisho Y., Shintani A., Nishida M., Fukumoto H., Igarashi K. (1994) Brain Res. 666, 143–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Katoh-Semba R., Takeuchi I. K., Semba R., Kato K. (1997) J. Neurochem. 69, 34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wulff K., Gatti S., Wettstein J. G., Foster R. G. (2010) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 589–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ibuka N., Kawamura H. (1975) Brain Res. 96, 76–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moore R. Y. (2007) Sleep Med. 8, 27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pollock G. S., Vernon E., Forbes M. E., Yan Q., Ma Y. T., Hsieh T., Robichon R., Frost D. O., Johnson J. E. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 3923–3931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hairston I. S., Peyron C., Denning D. P., Ruby N. F., Flores J., Sapolsky R. M., Heller H. C., O'Hara B. F. (2004) J. Neurophysiol. 91, 1586–1595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sadakata T., Washida M., Iwayama Y., Shoji S., Sato Y., Ohkura T., Katoh-Semba R., Nakajima M., Sekine Y., Tanaka M., Nakamura K., Iwata Y., Tsuchiya K. J., Mori N., Detera-Wadleigh S. D., Ichikawa H., Itohara S., Yoshikawa T., Furuichi T. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 931–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Katoh-Semba R., Takeuchi I. K., Inaguma Y., Ichisaka S., Hata Y., Tsumoto T., Iwai M., Mikoshiba K., Kato K. (2001) J. Neurochem. 77, 71–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Katoh-Semba R., Takeuchi I. K., Inaguma Y., Ito H., Kato K. (1999) Neurosci. Res. 35, 19–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sadakata T., Mizoguchi A., Sato Y., Katoh-Semba R., Fukuda M., Mikoshiba K., Furuichi T. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 43–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shinoda Y., Kamikubo Y., Egashira Y., Tominaga-Yoshino K., Ogura A. (2005) Brain Res. 1042, 99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Katoh-Semba R., Kaneko R., Kitajima S., Tsuzuki M., Ichisaka S., Hata Y., Yamada H., Miyazaki N., Takahashi Y., Kato K. (2009) Neuroscience 163, 352–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tao X., Finkbeiner S., Arnold D. B., Shaywitz A. J., Greenberg M. E. (1998) Neuron 20, 709–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhou Z., Hong E. J., Cohen S., Zhao W. N., Ho H. Y., Schmidt L., Chen W. G., Lin Y., Savner E., Griffith E. C., Hu L., Steen J. A., Weitz C. J., Greenberg M. E. (2006) Neuron 52, 255–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tao J., Hu K., Chang Q., Wu H., Sherman N. E., Martinowich K., Klose R. J., Schanen C., Jaenisch R., Wang W., Sun Y. E. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106, 4882–4887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sei H., Fujihara H., Ueta Y., Morita K., Kitahama K., Morita Y. (2003) Life Sci. 73, 53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huber R., Ghilardi M. F., Massimini M., Tononi G. (2004) Nature 430, 78–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xiong H., Futamura T., Jourdi H., Zhou H., Takei N., Diverse-Pierluissi M., Plevy S., Nawa H. (2002) Neuropharmacology 42, 903–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sutton G., Chandler L. J. (2002) J. Neurochem. 82, 1097–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McAllister A. K., Lo D. C., Katz L. C. (1995) Neuron 15, 791–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bartkowska K., Paquin A., Gauthier A. S., Kaplan D. R., Miller F. D. (2007) Development 134, 4369–4380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McAllister A. K., Katz L. C., Lo D. C. (1996) Neuron 17, 1057–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McAllister A. K., Katz L. C., Lo D. C. (1997) Neuron 18, 767–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Itami C., Kimura F., Nakamura S. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 2241–2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Luikart B. W., Zhang W., Wayman G. A., Kwon C. H., Westbrook G. L., Parada L. F. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 7006–7012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sanchez A. L., Matthews B. J., Meynard M. M., Hu B., Javed S., Cohen Cory S. (2006) Development 133, 2477–2486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Glantz L. A., Gilmore J. H., Hamer R. M., Lieberman J. A., Jarskog L. F. (2007) Neuroscience 149, 582–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Perez-Cruz C., Simon M., Flügge G., Fuchs E., Czéh B. (2009) Behav. Brain Res. 205, 406–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Conner J. M., Lauterborn J. C., Yan Q., Gall C. M., Varon S. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 2295–2313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gorski J. A., Zeiler S. R., Tamowski S., Jones K. R. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23, 6856–6865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. He J., Gong H., Luo Q. (2005) Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 16, 69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bender K. J., Allen C. B., Bender V. A., Feldman D. E. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 4155–4165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fawcett J. P., Bamji S. X., Causing C. G., Aloyz R., Ase A. R., Reader T. A., McLean J. H., Miller F. D. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 2808–2821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kushikata T., Fang J., Krueger J. M. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 276, R1334–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ohta H., Honma S., Abe H., Honma K. (2002) Eur. J. Neurosci. 15, 1953–1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Belmonte M. K., Allen G., Beckel-Mitchener A., Boulanger L. M., Carper R. A., Webb S. J. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 9228–9231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Minshew N. J., Williams D. L. (2007) Arch. Neurol. 64, 945–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chapleau C. A., Larimore J. L., Theibert A., Pozzo-Miller L. (2009) J. Neurodev. Disord. 1, 185–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Katoh-Semba R., Wakako R., Komori T., Shigemi H., Miyazaki N., Ito H., Kumagai T., Tsuzuki M., Shigemi K., Yoshida F., Nakayama A. (2007) Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 25, 367–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.