Abstract

All-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) induces growth arrest of many cell types. Previous studies have reported that ATRA can modulate cellular sphingolipids, but the role of sphingolipids in the ATRA response is not clear. Using MCF-7 cells as a model system, we show that ATRA stimulates an increase in ceramide levels followed by G0/G1 growth arrest. Notably, induction of nSMase2 was the primary effect of ATRA on the sphingolipid network and was both time- and dose-dependent. Importantly, pretreatment with nSMase2 siRNA significantly inhibited ATRA effects on ceramide levels and growth arrest. In contrast, nSMase2 overexpression was sufficient to increase ceramide levels and induce G0/G1 growth arrest of asynchronous MCF-7 cells. Surprisingly, neither ATRA stimulation nor nSMase2 overexpression had significant effects on classical cell cycle regulators such as p21/WAF1 or retinoblastoma. In contrast, ATRA suppressed phosphorylation of ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K) and its downstream targets S6 and eIF4B. Importantly, these effects were significantly inhibited by nSMase2 siRNA. Reciprocally, nSMase2 overexpression was sufficient to suppress S6K phosphorylation and signaling. Notably, neither ATRA effects nor nSMase2 effects on S6K phosphorylation required the ceramide-activated protein phosphatase PP2A, previously identified as important for S6K regulation. Finally, nSMase2 overexpression was sufficient to decrease translation as measured by methionine incorporation and analysis of polyribosome profiles. Taken together, these results implicate nSMase2 as a major component of ATRA-induced growth arrest of MCF-7 cells and identify S6K as a novel downstream target of nSMase2.

Keywords: Cell Cycle, mTOR, Protein Synthesis, S6 Kinase, Sphingolipid, Translation, Ceramide, Neutral Sphingomyelinase, Retinoic Acid

Introduction

Sphingolipids such as ceramide (Cer)2 are a class of bioactive lipids implicated in a variety of physiological processes. In particular, Cer is thought to be involved in apoptosis, inflammation, and the cellular response to cytokines and other stresses (1). Cer production can occur through multiple pathways and is under tight control within the cell. Sphingomyelinases (SMases) produce Cer through hydrolysis of sphingomyelin and are considered important mediators of stress-induced Cer production (2). Currently, three families of SMases have been identified and are classified by the pH optima of their activity. Of these, both acid and neutral SMases (N-SMases) have been reported to contribute to stress and cytokine-induced Cer production (2, 3).

Currently, four mammalian N-SMases have been cloned and characterized: nSMase1, nSMase2, nSMase3, and the recently identified mitochondria-associated nSMase. Of these, studies have implicated nSMase2 in the acute responses to cytokines, chemotherapeutic drugs, and oxidative stress (2). Importantly, emerging evidence is beginning to suggest a more protracted mode of nSMase2 regulation involving changes in nSMase2 gene expression. For example, increased nSMase2 expression has been demonstrated in confluence-induced growth arrest of MCF-7 cells (4) and in rat 3Y1 cells where the CCA1 gene (for cell confluence arrest gene) was subsequently found to encode nSMase2 (5). Increased nSMase2 expression was also reported in mature osteoblasts compared with mesenchymal precursors (6), in bone morphogenetic protein 2-stimulated mouse C2C12 cells (7), and in daunorubicin-stimulated MCF-7 cells (8). However, the functional consequences of increased nSMase2 expression are largely unclear.

All-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) is the most potent member of a family of bioactive retinoids derived from vitamin A. The effects of ATRA are mediated by nuclear retinoic acid receptors with subsequent transcription of target genes that propagate the cellular response (9). ATRA is used as a therapeutic for acute promyelocytic leukemias and breast cancers, and loss of ATRA responsiveness is often a hallmark of more aggressive cancers (9, 10). However, although ATRA is known to induce a growth arrest in many cell types, the underlying mechanisms by which this occurs remain an area of intense research. A handful of studies have suggested that ATRA can regulate cellular sphingolipid levels; for example, ATRA stimulation increased acid SMase expression in NB4 cells and alkaline ceramidase-2 in HeLa cells but suppressed transcription of Cer kinase in neuroblastoma cells (11–13). Moreover, ATRA increased de novo Cer synthesis in human neuroblastoma cell lines (14). More recently, prolonged ATRA stimulation (72 h) of estrogen receptor-positive T47D cells increased nSMase2 expression and Cer and decreased expression of sphingosine kinase 1, responses that were suggested to be important for a reduction in cell proliferation (15). However, despite these studies, the wider effects of ATRA on the whole sphingolipid network are unknown. Furthermore, the direct functional role of sphingolipids in ATRA-induced growth arrest has yet to be explored.

In this study, we have utilized estrogen receptor-positive MCF-7 cells as a model system to probe the role of nSMase2 and sphingolipids in ATRA-induced growth arrest. We report that ATRA increases Cer levels and growth arrest through nSMase2 induction and find that nSMase2 is the key ATRA-regulated enzyme in the sphingolipid network of MCF-7 cells. In addition, we have identified p70 ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K) as a downstream effector of ATRA and nSMase2 and demonstrate that increased expression of nSMase2 negatively regulates S6K signaling and translation. Notably, nSMase2 does not regulate S6K through the ceramide-activated protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), a previously established regulator of S6K (16, 17) and downstream effector of nSMase2 (18). Taken together, these data identify nSMase2 as a novel regulator of translation through modulation of S6K activity and downstream signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

MCF7 breast carcinoma cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). RPMI culture medium, fetal bovine serum, blasticidin S HCl, and SuperScript reverse transcriptase were obtained from Invitrogen. Antibodies for nSMase2 (H195), PP2A-α/β (C-20), p21/WAF1 (C19), and cyclin B1 (GNS1) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). All other antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). The enhanced chemiluminescence kit was from ThermoScientific (Rockford, IL). Porcine brain sphingomyelin and phosphatidylserine were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Retinoic acid, TDZD-8, compound C, and, unless indicated otherwise, all other chemicals were obtained from Sigma.

Cell Culture and siRNA

MCF-7 cells were maintained in 10% fetal bovine serum in RPMI (Invitrogen) at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. For MCF-7 cells stably expressing LacZ or nSMase2, medium was supplemented with 7 μg/ml blasticidin. The cells were subcultured in 60-mm (200,000 cells) and 100-mm (500,000 cells) dishes for experiments, and the medium was changed 1–2 h prior to the start of experiments. For siRNA experiments, the cells were seeded in 60-mm (150,000 cells) or 1000mm (300,000 cells) dishes. After 24 h, the cells were transfected with 20 nm negative control (AllStar; Qiagen) or nSMase2 siRNA (Qiagen) using Oligofectamine according to manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). After 30 h, the cells were incubated in fresh medium for 1–2 h prior to stimulation. The siRNA for nSMase2 was designed against the targeting sequence CAGGCCCATCTTCAACAGCTA. The siRNA for PP2A was purchased from Santa Cruz (sc-44033).

Protein Extraction and Immunoblot Analysis

To extract cellular protein, the cells were scraped in RIPA buffer and lysed by sonication. Protein concentration was estimated by the Bradford assay, and aliquots of lysates were mixed with equal volumes of 2× Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad), vortexed, and boiled for 5–10 min. Where indicated, the protein was also extracted by direct lysis in 1× Laemmli buffer. Following addition, the cells were freeze-thawed, and the lysates were transferred to 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and boiled for 5–10 min. The protein was separated by SDS-PAGE using the Criterion system (Bio-Rad) and immunoblotted as described previously.

Real Time PCR

Following stimulation, mRNA from MCF-7 cells was extracted using the RNAEasy kit (Qiagen). 0.5–1 μg of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA with the SuperScript II kit for first strand synthesis (Invitrogen). Real time RT-PCR was performed on a Bio-Rad iCycler detection system using iQ SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad). Standard reaction volume was 25 μl containing 12.5 μl of supermix, 6.5 μl of distilled H2O (Sigma), 100–500 nm oligonucleotide primers (IDT), and 5 μl of cDNA template (diluted 12× in molecular biology grade distilled H2O). Initial steps of RT-PCR were 2 min at 50 °C for UNG erase activation, followed by a 3-min hold at 95 °C for enzyme activation. For all primers, cycles (n = 40) consisted of a 10-s melt at 98 °C, followed by a 45-s annealing at 55 °C and a 45-s extension at 68 °C. The final step was 55 °C incubation for 1 min. All of the reactions were performed in triplicate, and the threshold for cycle of threshold (Ct) analysis of all samples was set at 0.15 relative fluorescence units. The data were normalized to an internal control gene, actin, to control for RNA preparation. Analysis of a single PCR product was confirmed by melt-curve analysis. Primers used were as follows: nSMase2(F), 5′-AGGACTGGCTGGCTGATTTC-3′; nSMase2(R), 5′-TGTCGTCAGAGGAGCAGTTATC-3′; CerS2(F), 5′-CCGATTACCTGCTGGAGTCAG-3′; CerS2(R), 5′-GGCGAAGACGATGAAGATGTTG-3′; DEGS1(F), 5′-AGGACTGGCTGGCTGATTTC-3′; DEGS1(R), 5′-TACATCGACGCCATCAGCTCCAAG-3′; Actin(F), 5′-ATTGGCAATGAGCGGTTCC-3′; and Actin(R), 5′-GGTAGTTTCGTGGATGCCACA-3′.

Sphingolipid Array

To facilitate analysis of gene expression for the wider sphingolipid network, a custom PCR array was developed in conjunction with SA Biosciences. Primers were designed against the cDNA regions of the genes shown. Actin and GAPDH were utilized as reference genes. To run the assay, a MasterMix of 637.5 μl of SYBR-green, 51 μl of cDNA, and 586.5 μl of distilled H2O was prepared for each cDNA template. 25 μl was loaded per well. The RT-PCR protocol consisted of 10 min at 95 °C for polymerase activation followed by 40 cycles of a 15-s melt at 95 °C and 60 s at 60 °C for annealing and extension. After the cycles were run, a melt curve was performed to confirm a single product for each primer pair. The data were analyzed utilizing the PCR array data analysis portal at the SABiosciences web site.

Neutral Sphingomyelinase Assay

N-SMase activity was assayed in vitro as described previously (4) utilizing 14C-[methyl]sphingomyelin as substrate.

Analysis of Cellular Sphingolipids

For all lipid experiments, the cells were incubated in serum-free medium (RPMI with 0.1% fatty-acid free BSA) for 3–5 h prior to stimulation or collection. The cells were washed, scraped in cold PBS, and collected by centrifugation. The cell pellets were stored at −80 °C prior to extraction and analysis by tandem LC/MS mass spectrometry, and lipid levels were normalized to the total lipid phosphate level of the sample as described (19).

Analysis of Cell Cycle by Flow Cytometry

After treatment of cells as indicated, the cells were washed in cold PBS, scraped, and pelleted. The pellets were resuspended in −20 °C 70% ethanol and placed at 4 °C overnight. On the day of analysis, the cells were pelleted and ethanol-aspirated. The cells were then resuspended in 0.5 ml of hypotonic staining solution (0.25 g of sodium citrate, 0.75 ml of Triton X-100, 0.025 g of propidium iodide, 0.005 g of ribonuclease A in 250 ml of water) for 30 min and analyzed with a FACStarPLUS flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Methionine Labeling

MCF7-LacZ and -NSM2 cells were plated in six-well trays (150,000 cells/well) for 24 h. Medium was changed, and the cells were incubated for 48 h. Following a wash with sterile PBS, the cells were incubated in methionine-free RPMI (Sigma) for 1 h and then incubated for 1 h in methionine-free RPMI containing 10 μCi/ml [35S]methionine (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The cells were washed and scraped in RIPA buffer and lysed by three snap freeze-thaw cycles. [35S]Methionine incorporation into TCA-precipitable material was determined.

Polysome Profile Analysis

MCF7-LacZ and NSM2 cells were plated in four 150-mm dishes each (1 × 106/dish), and after 24 h, the medium was changed for 48 h. The cells were incubated in cycloheximide (0.1 mg/ml) for 30 min, washed once, and scraped in PBS with cycloheximide, and collected by centrifugation. From cell pellets, cytoplasmic extracts were prepared in hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 7.2, 10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 20 mm dithiothreitol, 0.150 mg/ml cycloheximide, 0.5 mg/ml heparin, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 100 units/ml RNasin) and fractionated on a 7–47% sucrose gradient buffered with 10 mm Tris acetate, pH 7.2, 10 mm MgCl2, and 10 mm KCl. The gradients were centrifuged in an SW41 rotor at 41,000 rpm for 120 min at 4 °C. After ultracentrifugation, the tubes were punctured at the bottom, and the fractions were displaced upwards using Fluorinert FC-40 (Sigma). Absorbance was monitored continuously at 254 nm using ISCO-UA45 (model 640) density gradient fraction collector.

Statistical Analysis

The data are represented as the means ± S.E., unless otherwise indicated. For comparison of two groups, unpaired Student's t test was utilized with p < 0.05 being considered statistically significant and n = number of experiments as indicated.

RESULTS

ATRA-induced Growth Arrest Occurs Subsequent to Cer Generation in MCF-7 Cells

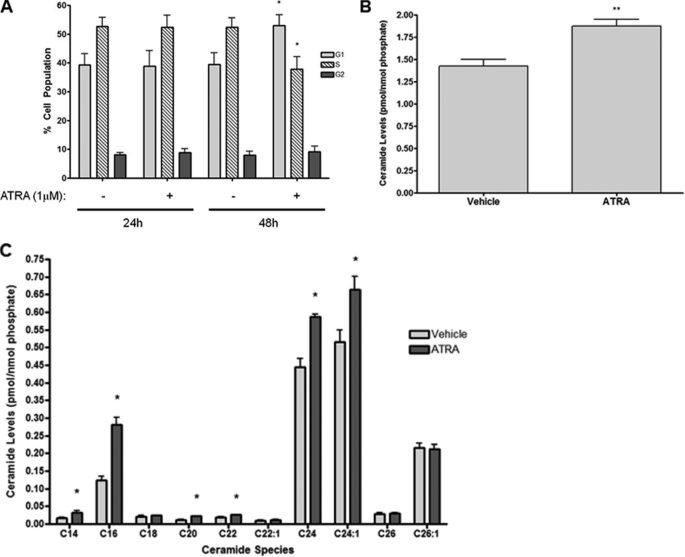

ATRA has been reported to modulate sphingolipids and induces growth arrest of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells, but the role of sphingolipids in this is unclear. To study this further, estrogen receptor-positive MCF-7 cells were utilized as a model system. Previously, our lab reported effects of cell growth and confluence on sphingolipid levels of MCF-7 cells (4). Thus, to ensure that this was not a factor, the cells were seeded at low density to remain subconfluent throughout experiments. As can be seen (Fig. 1A), ATRA stimulation (1 μm, 48 h) significantly increased cells in G1 phase (53.0 ± 3.7% versus 39.4 ± 4.0%, p < 0.05) with a concomitant decrease in the S phase (37.8 ± 4.3% versus 52.3 ± 3.3%, p < 0.05) compared with vehicle control with a minimal effect on the G2/M phase population (9.2 ± 1.8% versus 8.0 ± 1.3%, p > 0.25). Notably, cell cycle distribution was unchanged by 24 h of ATRA stimulation (Fig. 1A). Analysis of cellular sphingolipid levels at the 24-h time point, prior to cell cycle arrest, showed that ATRA induced a significant increase in total Cer levels (Fig. 1B). Analysis of individual species at 24 h of ATRA stimulation showed that the major changes were of the C16, C24, and C24:1 Cer species (Fig. 1C). Thus, in the ATRA response, cellular Cer levels increase prior to growth arrest.

FIGURE 1.

ATRA induces growth arrest subsequent to ceramide production in MCF-7 cells. A, MCF-7 cells were seeded in 100-mm dishes and stimulated with either vehicle or ATRA for 24 or 48 h. The cells were collected and fixed, and cell cycles were analyzed by flow cytometry as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data are presented as the means ± S.E. % total cell population. *, p < 0.05 (n = 4). B and C, MCF-7 cells were seeded in 100-mm dishes and serum-starved for 3 h prior to stimulation with ATRA for 24 h. The cells were collected, and ceramide levels were analyzed by tandem LC/MS mass spectrometry. B, data are presented as the mean ± S.E. total ceramide levels normalized to total cellular phosphate. C, data are presented as the mean ± S.E. levels of individual ceramide species normalized to total cellular phosphate.

Induction of nSMase2 Is the Primary Effect of ATRA on the Sphingolipid Network

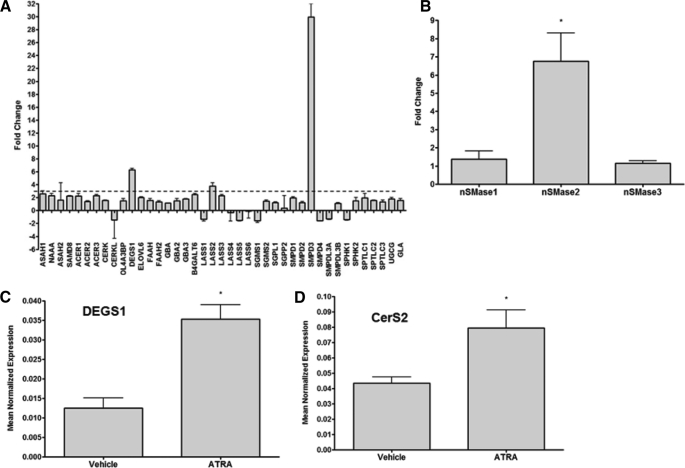

ATRA has previously been shown to modulate sphingolipid metabolizing enzymes (11–13, 15). However, the wider effects of ATRA on the sphingolipid network are unclear. Because ATRA largely acts through binding to nuclear receptors and regulation of expression of target genes, the effects of ATRA on sphingolipid enzyme expression were investigated utilizing a custom-designed PCR array in cells treated with vehicle or ATRA for 24 h (Fig. 2A). Notably, of the 42 genes investigated (see supplemental Table S1 for gene names), only three genes exhibited an up-regulation of >3-fold: nSMase2 (SMPD3), dihydroceramide desaturase-1 (DEGS1), and Cer synthase 2 (CerS2, also known as LASS2) as seen in Fig. 2A. Of these, nSMase2 exhibited the greatest effect, with ∼30-fold induction seen compared with vehicle control by PCR array. Validation of these results by real time PCR confirmed a significant up-regulation of nSMase2 (7–8-fold) but not nSMase1 or nSMase3 in response to ATRA stimulation (Fig. 2B). Real time PCR also confirmed a significant up-regulation of CerS2 and DEGS1 (Fig. 2, C and D). Together, these results show that nSMase2 is the key sphingolipid metabolic enzyme regulated by ATRA in MCF-7 cells, suggesting that nSMase2 may play a role in the ATRA response.

FIGURE 2.

nSMase2 is a key ATRA-regulated node in the sphingolipid network of MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes and stimulated with vehicle or ATRA for 24 h. RNA was extracted and converted to cDNA for analysis by real time PCR as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, ATRA effects on the sphingolipid network were assessed by PCR array. The data are presented as fold change ATRA/vehicle and are means of two experiments. The dashed line represents a 3-fold change. B–D, validation of array results for nSMase1, 2, and 3 (B); DEGS1 (C); and CerS2 (D) was performed by real time PCR. The data are presented as the means ± S.E. mean normalized expression. *, p < 0.05 (n > 3).

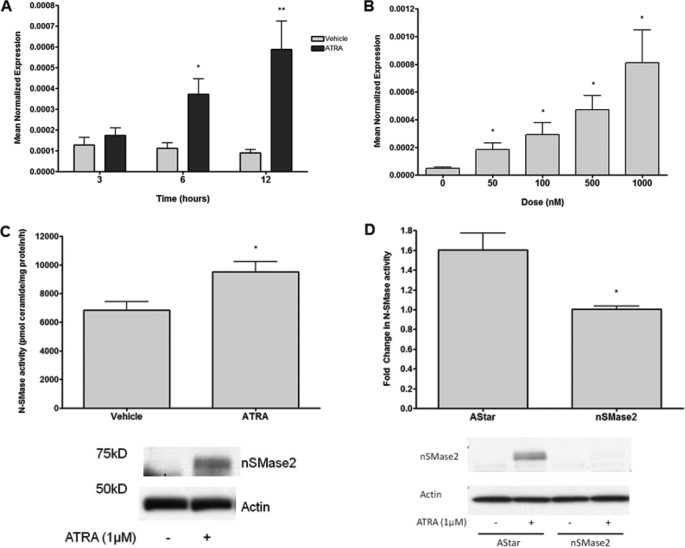

ATRA Regulation of nSMase2

To further characterize the effects of ATRA on nSMase2, a time and dose response was performed. As can be seen, ATRA increased nSMase2 mRNA as early as 6 h with further increases by 12 h (Fig. 3A), and these effect were highly dose-dependent, with doses as low as 50 nm ATRA able to significantly increase nSMase2 expression (Fig. 3B). Importantly, this is well within physiological ATRA concentrations (20). Consistent with the observed increase in nSMase2 expression, ATRA stimulation of MCF-7 cells also significantly increased nSMase2 at the protein level (Fig. 3C, bottom panel) and significantly increased endogenous N-SMase activity (Fig. 3C, top panel). Importantly, pretreatment with nSMase2 siRNA strongly inhibited ATRA effects on nSMase2 mRNA (data not shown), nSMase2 protein, and N-SMase activity (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these results confirm that ATRA acutely increases nSMase2 levels leading to increased N-SMase activity in MCF-7 cells.

FIGURE 3.

ATRA regulates nSMase2 in a time- and dose-dependent manner. A and B, MCF-7 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes and stimulated with vehicle or 1 μm ATRA for the times indicated (A) or vehicle or various doses of ATRA for 12 h (B). RNA was extracted, and nSMase2 expression was analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data are presented as the means ± S.E. of mean normalized expression. *, p < 0.05 (n > 4). C, MCF7 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes and stimulated with 1 μm ATRA for 12 h. N-SMase activity was extracted and assayed in vitro as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data are presented as the means ± S.E. pmol ceramides/mg of protein/h. *, p < 0.05 (n > 3). Lysates were analyzed for nSMase2 levels by immunoblot with actin as loading control. The immunoblot shown is representative of three experiments. D, MCF7 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes and treated with negative control (AStar) or nSMase2 siRNA for 30 h prior to stimulation with vehicle or ATRA for 24 h. N-SMase activity was extracted and assayed in vitro as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data are presented as the means ± S.E. fold change (ATRA over vehicle). *, p < 0.05 (n > 3). The lysates were analyzed for nSMase2 levels by immunoblot with actin as loading control. The immunoblot shown is representative of three experiments.

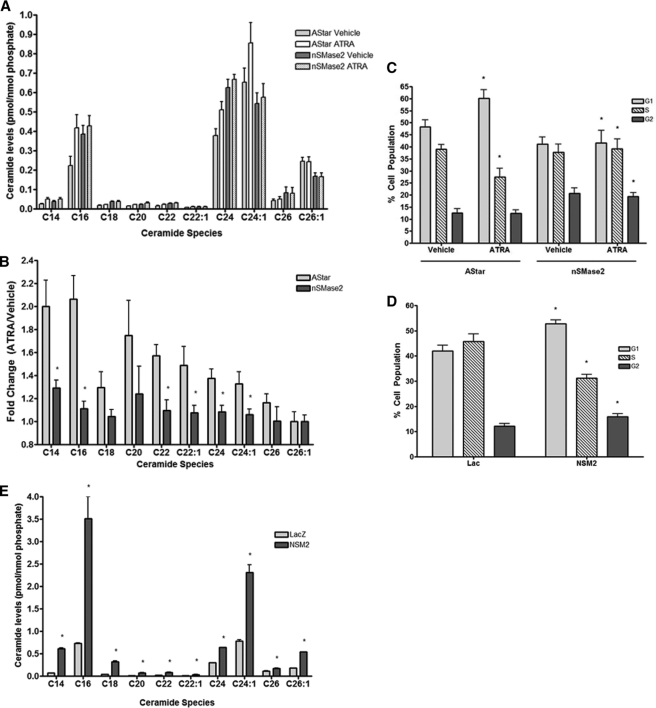

ATRA-induced Cer Production and Growth Arrest Is nSMase2-dependent

The above data suggested nSMase2 is the key sphingolipid enzyme in the ATRA response. To confirm this, the effects of nSMase2 siRNA on ATRA-induced Cer production and growth arrest were assessed (Fig. 4). Surprisingly, nSMase2 siRNA treatment alone caused a basal increase in Cer levels. Nonetheless, and more importantly, nSMase2 siRNA inhibited the increase in Cer seen with ATRA stimulation (Fig. 4, A and B). Importantly, nSMase2 siRNA also prevented the ATRA-induced increase in G1 phase cells (41.6 ± 5.2% versus 60.2 ± 3.6%, p < 0.02) (Fig. 4C). Thus, nSMase2 modulation of Cer levels plays a key role in ATRA-induced growth arrest.

FIGURE 4.

ATRA induction of ceramide and growth arrest is nSMase2-dependent in MCF-7 cells. A and B, MCF7 cells were seeded in 100-mm dishes and treated with negative control (AStar) or nSMase2 siRNA for 30 h. The cells were serum-starved for 3 h prior to stimulation with vehicle or ATRA for 24 h. The cells were collected, and ceramide levels were analyzed by tandem LC/MS mass spectrometry as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The results are presented as follows. A, mean ± S.E. levels of individual ceramide species normalized to total lipid phosphate. B, mean ± S.E. fold change of individual lipid species (ATRA versus vehicle) for negative control (AStar) and nSMase2 siRNA. *, p < 0.05 (n > 4). C, MCF7 cells were seeded in 100-mm dishes and treated with negative control (AStar) or nSMase2 siRNA for 30 h prior to stimulation with vehicle or ATRA for 48 h. Cell cycle distribution was analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” *, p < 0.05 (n = 4). D, MCF7-LacZ and -NSM2 stable cells were seeded in 100-mm dishes and stimulated with vehicle or ATRA for 48 h. Cell cycle distribution was analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” *, p < 0.05 (n = 4). The data are presented as the means ± S.E. % total cell population. E, MCF7-LacZ and -NSM2 stable cells were seeded in 100-mm dishes for 48 h and serum-starved for 5 h. The cells were collected, and ceramide levels were analyzed by tandem LC/MS mass spectrometry as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The results are presented as the mean ± S.E. levels of individual ceramide species normalized to total lipid phosphate. *, p < 0.05 (n = 3).

Previous research from our lab showed that overexpression of nSMase2 delayed release of serum-starved cells from G0/G1 arrest (4). However, the effect of nSMase2 overexpression on the cell cycle of asynchronous growing cells was not determined. Here, we find that stable nSMase2 overexpression significantly increased G1 phase cells by 48 h compared with LacZ controls (51.9 ± 1.4% versus 44.5 ± 3.0%, p < 0.02) with a concomitant decrease in the S phase (Fig. 4D). Moreover, this correlated with significant increases in the levels of C16, C24, and C24:1 Cer (Fig. 4E). Thus, stable nSMase2 overexpression is sufficient to increase Cer levels and induce G0/G1 growth arrest of MCF-7 cells.

ATRA and nSMase2 Negatively Regulate Ribosomal S6 Kinase

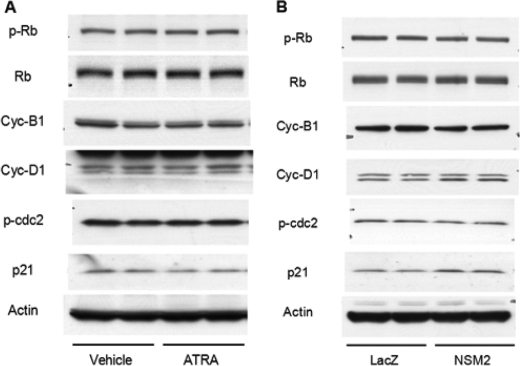

To mechanistically determine how ATRA and nSMase2 regulate cell cycle arrest, a number of cell cycle regulators such as cyclin D1, cyclin B1, phosphorylation of retinoblastoma, and p21/WAF1 were investigated. Surprisingly, ATRA had little to no effect on the levels of any of the proteins analyzed or the degree of retinoblastoma phosphorylation (Fig. 5A). This was also the case in MCF7-NSM2 cells at 48 h compared with LacZ controls (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

ATRA and nSMase2 do not have major effects on classical cell cycle regulators. A, MCF7 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes and stimulated with vehicle or ATRA (1 μm) for 48 h. The cells were directly lysed in Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting as indicated. The immunoblot shown is representative of three experiments. B, MCF7-LacZ and -NSM2 stable cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes, medium was changed, and the cells were allowed to grow for 48 h. The samples were processed as in A and immunoblotted as shown. The immunoblot shown is representative of three experiments.

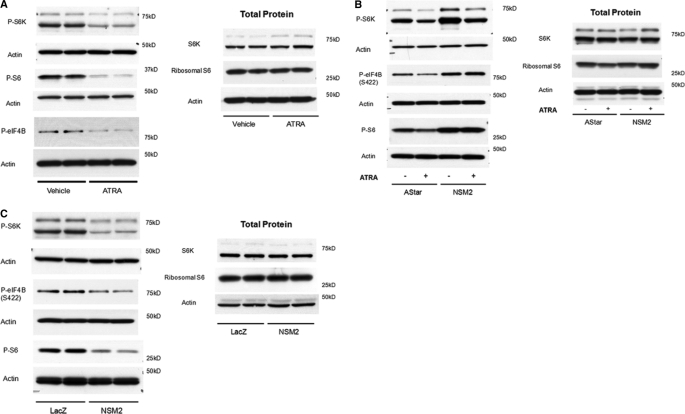

S6K is also known to regulate G1-S transition, and both pharmacological and siRNA inhibition of S6K activity induces a G0/G1 arrest. Serum starvation also causes dephosphorylation of S6K and induces G0/G1 arrest (21, 22). Because we had previously observed that serum withdrawal increased nSMase2 expression,3 we speculated that S6K may play a role in both ATRA and nSMase2-induced growth arrest. Analysis of S6K phosphorylation on Thr-389 indicated that ATRA significantly suppressed phospho-S6K levels compared with vehicle control (Fig. 6A). Consistent with Thr-389 phosphorylation reflecting S6K activity (23), ATRA stimulation also decreased the phosphorylation of ribosomal S6 at Thr-37/46 and eIF4B at Ser-422, two known downstream effector sites of S6K (Fig. 6A). Importantly, pretreatment with nSMase2 siRNA significantly increased phospho-S6K, phospho-S6, and phospho-eIF4B levels in ATRA-stimulated cells when compared with negative control (AStar) siRNA cells. Notably, nSMase2 siRNA treatment significantly increased levels of phospho-S6K and phospho-S6 in vehicle-stimulated cells (Fig. 6B). Similarly, the levels of phospho-eIF4B were also increased, although this was not statistically significant (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

ATRA and nSMase2 regulate ribosomal S6 kinase phosphorylation and activity. A, MCF7 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes and stimulated in duplicate with vehicle (0.1% Me2SO) or ATRA (1 μm) for 48 h. The lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer as described under “Experimental Procedures” and analyzed by immunoblot as shown. The blots are representative of at least three independent experiments. B, MCF7 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes and transfected with negative control (AStar) or nSMase2 siRNA for 30 h prior to stimulation with vehicle (0.1% Me2SO) or ATRA (1 μm). The samples were processed as in A and immunoblotted as shown. The blots are representative of at least four independent experiments. C, MCF7-LacZ and -NSM2 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes in duplicate, the medium was changed, and the cells were allowed to grow for a further 48 h. The lysates were prepared as in A and analyzed by immunoblot as shown. The blots are representative of at least four independent experiments.

To corroborate these data, the effect of stable nSMase2 overexpression on the S6K pathway was assessed (Fig. 6C). Results showed that MCF7-nSMase2 cells displayed significantly lower levels of phospho-S6K than LacZ control cells. Importantly, both phospho-S6 and phospho-eIF4B levels were also decreased consistent with lower activity of S6K (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these results indicate that ATRA and nSMase2 induce growth arrest by suppressing S6K activity. Moreover, nSMase2 is both necessary and sufficient for the suppression of S6K activity.

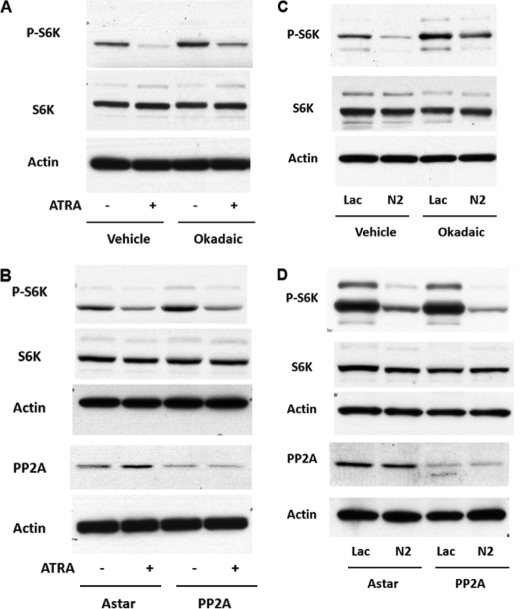

Effects of nSMase2 on S6 Kinase Are Independent of PP2A

Having established nSMase2 as a regulator of S6K, we next considered the mechanism by which nSMase2 may regulate S6K phosphorylation. A number of studies have identified the protein phosphatase PP2A as a key regulator of S6K (16, 17). Notably, nSMase2 has been reported to exert signaling effects through activation of PP2A (18). This prompted us to assess the role of PP2A in ATRA and nSMase2 regulation of S6K. Initially, the cells were pretreated with the PP2A inhibitor okadaic acid (25 nm) for 30 min prior to stimulation with vehicle or ATRA for 48 h (Fig. 7A). As can be seen, okadaic acid significantly increased phospho-S6K levels compared with vehicle controls. However, even in the presence of okadaic acid, ATRA stimulation still decreased phospho-S6K levels. To confirm these results, an siRNA approach was utilized (Fig. 7B). PP2A immunoblots confirmed efficacy of the siRNA at decreasing PP2A protein levels. As with okadaic acid, siRNA knockdown of PP2A tended to increase phospho-S6K levels compared with negative control siRNA-treated samples (AStar). However, PP2A siRNA did not significantly inhibit the ATRA-stimulated decrease in phospho-S6K. Importantly, total S6K levels remained unaffected by any of the above treatments. Taken together, these results indicate that PP2A is not required for ATRA regulation of S6 kinase.

FIGURE 7.

ATRA and nSMase2 regulate S6K phosphorylation independently of PP2A. A, MCF7 cells were plated in six-well trays (180,000 cells/well), and 24 h later, the medium was changed. The cells were treated with okadaic acid (20 nm) for 15 min prior to stimulation with vehicle or ATRA for 48 h. The lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer as described under “Experimental Procedures” and analyzed by immunoblot as shown. The blots are representative of at least three independent experiments. B, MCF7 cells were plated in 60-mm dishes (150,000 cells) and, 24 h later, treated with negative control (AStar) or PP2A-α siRNA (20 nm). After 30 h, the medium was changed 1 h prior to stimulation with vehicle or ATRA for 48 h. The lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer as described under “Experimental Procedures” and analyzed by immunoblot as shown. The blots are representative of at least three independent experiments. C, MCF7-LacZ and -NSM2 cells were plated in six-well trays (180,00 cells/well), and 24 h later, the medium was changed. The cells were treated with vehicle (Me2SO) or okadaic acid (20 nm). 48 h later, the lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer as described under “Experimental Procedures” and analyzed by immunoblot as shown. The blots are representative of at least three independent experiments. D, MCF7 cells were plated in 60-mm dishes (150,000 cells) and, 24 h later, treated with negative control (AStar) or PP2A-α siRNA (20 nm). After 6–8 h, the medium was changed, and 48 h later, the lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer as described under “Experimental Procedures” and analyzed by immunoblot as shown. The blots are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Having determined this, it next became important to confirm that PP2A does not mediate effects of nSMase2 overexpression on S6 kinase. Initially, MCF7-LacZ and -NSM2 cells were incubated with the PP2A inhibitor okadaic acid (25 nm) over the 48 h of the experiment (Fig. 7C). Notably, okadaic acid treatment enhanced levels of phospho-S6K in both -LacZ and -NSM2 cells consistent with a role for PP2A in regulation of S6K. However, as can be seen, phospho-S6K levels remained lower in NSM2 cells compared with LacZ, suggesting that PP2A is not required for the nSMase2-mediated decrease in phospho-S6K levels. As above, siRNA knockdown of PP2A was utilized to consolidate inhibitor data (Fig. 7D). Again, PP2A immunoblots confirmed significant knockdown of PP2A at the protein levels. Importantly, as with ATRA stimulation, PP2A siRNA did not significantly inhibit the effect of NSM2 on S6K phosphorylation. Taken together, these results suggest that nSMase2 does not regulate S6 kinase through PP2A.

ATRA Effects on S6K Are Not through mTOR Phosphorylation, AMP Kinase, or GSK3β

The lack of a role for PP2A in ATRA effects on S6K suggested that upstream pathways of S6K regulation could be affected. To assess this initially, phosphorylation of mTOR at Ser-2448, previously shown to be sensitive to growth factors, serum, and amino acid levels and downstream of Akt (24), and Ser-2481, a similarly regulated autophosphorylation site (25), was examined (supplemental Fig. S1). However, neither ATRA nor nSMase2 overexpression had effects on phospho-mTOR levels at either residue. Thus, ATRA and nSMase2 do not regulate S6K by modulating mTOR phosphorylation.

Independently of mTOR phosphorylation, AMP kinase and glycogen-synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) pathways are well established as negative regulators of the mTOR complex 1-S6K pathway (26). Notably, ceramide has been reported to activate both AMPK and GSK3β (27, 28). Thus, ATRA regulation of S6K could occur through activation of these two enzymes. To probe this, the effects of ATRA on AMPK phosphorylation at Thr-172, a key site for activity (29), and GSK3β phosphorylation at Ser-9, a reflection of the inactive protein (30), were determined (supplemental Fig. S2A). As shown, ATRA did not significantly affect the phosphorylation of either protein at 24 or 48 h of stimulation, suggesting that AMPK and GSK3β are not involved in the ATRA response. To confirm this, we utilized pharmacological inhibitors of AMPK (Compound C) and GSK3β (TDZD-8) (26). MCF7 cells were incubated with vehicle, compound C (5 μm), or TDZD-8 (20 μm) for 30 min prior to stimulation with vehicle or ATRA for 48 h (supplemental Fig. S2B). As can be seen, neither inhibitor prevented ATRA effects on phospho-S6K. Taken together, this suggests that ATRA regulation of S6K is not through the AMPK and GSK3β pathways.

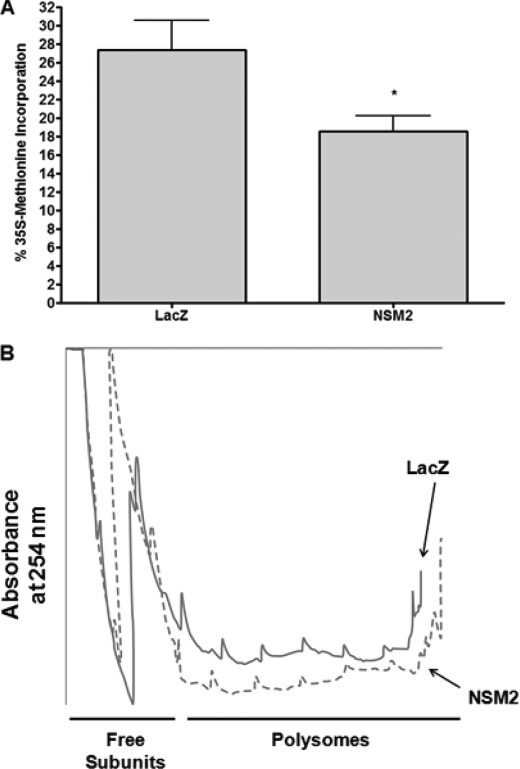

Regulation of Translation by nSMase2 in MCF-7 Cells

S6K is a well established regulator of translation (21, 22). Thus, the data above suggested that nSMase2 may be a novel regulator of this process through inhibiting S6K. Utilizing stable cell lines, the effects of nSMase2 overexpression on protein synthesis were assessed by [35S]methionine incorporation. As can be seen, there was significantly less incorporation of [35S]methionine in MCF7-NSM2 cells compared with LacZ control, suggesting a reduction in protein synthesis (Fig. 8A). Importantly, pretreatment with cycloheximide for 30 min nearly completely abrogated [35S]methionine incorporation, confirming efficacy of the assay (data not shown).

FIGURE 8.

nSMase2 is a negative regulator of translation. A, MCF7-LacZ and -NSM2 cells were plated in six-well trays, the medium was changed, and the cells were allowed to grow for 48 h. Protein synthesis was assessed by [35S]methinonine incorporation into TCA-precipitatable material as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data are shown as the means ± S.E. % incorporation (p < 0.05, n = 4). B, MCF7-LacZ and -NSM2 cells were plated in four 150-mm dishes, the medium was changed, and the cells were allowed to grow for 48 h. Polyribosome profiles were analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The traces shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Because the overall translational efficiency in cells is reflected by changes in the polysome/monosome ratio, the effect of nSMase2 overexpression on polyribosome profiles was determined using cytosolic extracts of MCF-LacZ and MCF7-NSM2 cells (Fig. 8B). As can be seen, NSM2 cells showed a significant reduction in heavy polysomes with a corresponding increase in free ribosome subunits, suggesting significant translational reduction in N2 cells compared with controls. These data, together with the methionine-incorporation results, indicate that nSMase2 overexpression is sufficient to suppress translation in MCF-7 cells.

DISCUSSION

In this study, nSMase2 was identified as a key node in the sphingolipid network that is essential for ATRA-regulated growth arrest of MCF-7 cells. This study also identifies S6K and S6 as novel downstream targets of nSMase2 in the ATRA response and demonstrates that nSMase2 overexpression is sufficient to negatively regulate S6K phosphorylation, signaling, and protein synthesis. These data shed light on the cellular mechanisms by which both ATRA and nSMase2 regulate cell proliferation and provide insight into the functional roles of sphingolipids in the ATRA response.

Regulation of p70 S6 Kinase and Translation by nSMase2

S6K is a downstream effector of the mTOR complex 1 and functions to regulate proliferation, cell size, and translation in response to nutrients, amino acids, and growth factors (21, 22). A major finding of the current study is the identification of S6K as a novel downstream target of nSMase2 in the ATRA-induced pathway. Importantly, the data show that both induction of endogenous nSMase2 by ATRA and stable overexpression of nSMase2 are sufficient to negatively regulate S6K phosphorylation at Thr-389. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate negative regulation of S6K by ATRA. Although a previous study reported activation of S6K by ATRA in MCF-7 cells (31), different phosphorylation sites on S6K were analyzed (Thr421/Ser424). Importantly, that study did not determine the effects of ATRA on downstream S6K effectors in MCF-7. In contrast, in this study, consistent with previous reports that Thr-389 is an accurate reflection of S6K activity (23), phosphorylation of the downstream S6K effectors S6 and eIF4B were also suppressed by ATRA stimulation and nSMase2 overexpression. Importantly, inhibition of the S6K pathway by nSMase2 was functionally important, resulting in decreased translation as evidenced by a reduction in [35S]methionine incorporation and a significant alteration in polyribosome profiles of MCF-7 cells. Notably, the effect of nSMase2 overexpression seen here (Fig. 8) was comparable with the effects of the pharmacological compound metformin, previously shown to modulate S6K and translation in MCF-7 cells (32). Overall, these data identify a novel role for nSMase2 as a negative regulator of translation and through modulation of S6K activity and signaling. Notably, because S6K signaling is often dysregulated in cancers (33), activation of endogenous nSMase2 may constitute a viable means to put a “brake” on the dysregulated signaling. It should also be noted that nSMase2 siRNA significantly increased phosphorylation of S6 kinase and its downstream effectors, suggesting that a loss of nSMase2 may have favorable effects on cell proliferation. Because a loss of nSMase2 activity was reported in some leukemias (34) and a recent study reported epigenetic suppression of nSMase2 in some breast cancers (35), this suggests the possibility that a loss of nSMase2 expression and/or activity may be a contributing factor to dysregulated S6K signaling and its pathological effects.

Mechanistically, the effects of ATRA and nSMase2 on S6K phosphorylation do not appear to be mediated through PP2A, a ceramide-activated protein phosphatase, previously identified as a key regulator of S6K (16, 17) and reported to be downstream of nSMase2 in hepatocytes (18). Additionally, because nSMase2 has also been reported to act through other ceramide-activated protein phosphatases such as PP1c-γ (36), experiments were also performed with calyculin A, a more specific PP1 inhibitor. Similarly, no effects on ATRA or nSMase2 regulation of p-S6K were seen (data not shown). Thus, nSMase2 seems to be acting independently of ceramide-activated protein phosphatase effectors. We also considered the possibility that ATRA and nSMase2 regulate S6K by modulating upstream signaling pathways. To this end, we focused on AMPK and GSK3β because they have been reported to be activated by ceramide (27, 28) and are known negative regulators of mTOR complex 1-S6K signaling (26). However, our results again indicated that neither AMPK nor GSK3β were required for ATRA effects on S6K and suggested that ATRA does not directly regulate either protein. Moreover, neither ATRA nor nSMase2 affected phosphorylation of mTOR at Ser-2448 or Ser-2481. Notably, both residues are reported to be sensitive to insulin, amino acids, and growth factors and downstream of Akt (24, 25). Consequently, this suggests that ATRA and nSMase2 are not exerting their effects through the upstream Akt pathway of mTOR activation. Clearly, given the established complexity of mTOR regulation and signaling, further studies are required to fully elucidate how ATRA and nSMase2 regulate S6K.

nSMase2 Is the Primary Sphingolipid Regulated Enzyme in ATRA-stimulated MCF-7 Cells

Utilizing MCF-7 cells as a system of ATRA-induced growth arrest, the evidence presented here indicates that nSMase2 is a key ATRA-stimulated node in the sphingolipid network, with expression being elevated >7-fold. Notably, the induction of nSMase2 was rapid: within 6 h, suggesting that nSMase2 functions as an early ATRA responsive gene. The role of nSMase2 as a key ATRA-regulated gene was further borne out by the observed increases in nSMase2 protein and endogenous N-SMase activity. Notably, the extent of the increase in N-SMase activity (40–50%) does not appear to correlate with the increase in nSMase2 mRNA seen (7-fold). However, in vitro N-SMase activity reflects the activity of all N-SMase isoforms (nSMase1, nSMase2, nSMase3, and mitochondria-associated nSMase). Thus, nSMase2 likely contributes minimally to basal N-SMase activity but is responsible for all the ATRA-stimulated N-SMase activity. This was confirmed utilizing nSMase2 siRNA (Fig. 3D) as well as by the lack of effect of ATRA on nSMase1 or nSMase3 mRNA (Fig. 2A).

Although previous studies have suggested that ATRA can regulate sphingolipid metabolizing enzymes including Cer kinase, acid SMase, alkaline ceramidase-2, and sphingosine kinase 1 (11–13, 15), none of these enzymes showed increased expression in ATRA-stimulated MCF-7 cells. The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear. However, because ATRA acts through a number of retinoic acid receptor and RXR subtypes, this could be due to cell type-specific expression of retinoic acid receptor and RXR receptors. In addition to nSMase2, ATRA also increased expression of CerS2 and DEGS1, albeit not to the same extent as nSMase2. Both of these enzymes are components of the de novo Cer synthetic pathway, raising the possibility that ATRA may also activate this pathway. Consistent with this theory, a previous study reported that myriocin, an inhibitor of de novo Cer synthesis, partially blocked ATRA-induced Cer production and growth arrest of neuroblastoma cells (14). However, the relative contributions of de novo synthesis and nSMase2 to Cer production are likely to be cell type-specific and could also reflect different receptor expression; indeed, the greater effects of ATRA on nSMase2 expression together with the clear effects of nSMase2 siRNA on ATRA-induced Cer production suggest that, at least in MCF-7 cells, ATRA activation of nSMase2 is the dominant pathway of Cer production.

Finally, the fact that ATRA predominantly exerts its effects through mediating transcription of target genes suggests that nSMase2 is likely to be up-regulated at the transcriptional level. However, it is unclear whether this is through direct retinoic acid receptor regulation of the nSMase2 gene or through induction of an intermediate protein regulator. This is currently the subject of ongoing studies in our laboratory.

nSMase2-mediated Cer Production Is Crucial for ATRA-stimulated Growth Arrest

Sphingolipids have been implicated in a wide variety of physiological processes including apoptosis, inflammation, and differentiation (1). Of the bioactive sphingolipids, Cer is largely considered to be a pro-apoptotic, anti-growth molecule. The data here support and extend this paradigm, with ATRA increasing Cer levels prior to growth arrest. The key role of nSMase2 in the ATRA response of MCF-7 cells was supported by the inhibition of ATRA-induced Cer production and growth arrest by nSMase2 siRNA. This further underscores the requirement for Cer production for ATRA-induced growth arrest. In addition, nSMase2 overexpression significantly increased ceramide levels and induced a G1 growth arrest of asynchronously growing cells, although it should be noted that stable nSMase2 overexpression increases N-SMase activity and ceramide levels well above that seen with ATRA stimulation. Moreover, nSMase2 overexpression increases the levels of some ceramide species (C26, C26:1) that do not change with ATRA stimulation. We speculate that this is due to the overexpressed enzyme accessing pools of substrate that it normally does not have access to. Nonetheless, all of these studies together provide firm evidence supporting a role for nSMase2-derived Cer in ATRA-induced growth arrest.

The role of nSMase2 in growth arrest described here is consistent with previous reports of increased nSMase2 expression in confluent rat 3YI cells (4) and the earlier study from our laboratory implicating nSMase2-produced Cer in contact-induced growth arrest of MCF-7 cells (5). To our knowledge, this is the first time nSMase2 has been functionally implicated in growth arrest induced by an exogenous stimulus, but this does not appear to be a universal mechanism of growth arrest because neither transforming growth factor-β1 nor vitamin D3, previously shown to induce a G1 arrest in MCF-7 cells (37, 38), were observed to have effects on nSMase2.4 In contrast, links between Cer increases and G0/G1 arrest have been reported in a handful of studies. For example, down-regulation of neutral ceramidase in human endothelial cells by siRNA or gemcitabine increased C16, C24, and C24:1 Cer and caused G0/G1 cell cycle arrest (39). Similarly, ATRA stimulation of neuroblastoma cells induced a de novo pathway-mediated increase in C24 and C24:1 Cer and inhibition of cell growth (14). Also, siRNA knockdown of sphingosine kinase 1 increased Cer levels and induced G1 growth arrest in MCF-7 cells (40). Taken together, this suggests that increases in Cer levels may be a universal component of G0/G1 growth arrest. However, further studies are required to determine whether suppression of S6K activity is a general mechanism of Cer-mediated growth arrest.

Physiological Roles of nSMase2 in ATRA Signaling

The characterization of nSMase2 as an early ATRA-responsive gene that is regulated by physiological ATRA concentrations may also offer clues as to broader roles of this enzyme. For example, ATRA is well established as a regulator of cartilage and bone formation in during development (41). Additionally, studies in nSMase2 knock-out mice revealed a dwarfism phenotype characterized by delayed ossification of the long bones (42). These results took on greater significance when a mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta, the fro/fro mouse, was found to possess a mutation in the nSMase2 gene resulting in the production of an inactive enzyme (43). Taken together, this raises the intriguing possibility that nSMase2 could play a functional role in ATRA signaling in the developing skeleton. Overall, the physiological implications of ATRA-mediated sphingolipid signaling, particularly through nSMase2, warrants further investigation.

Conclusions

In summary, this study has identified nSMase2 as a key mediator of ATRA-induced growth arrest of MCF-7 cells by regulating p70 ribosomal S6 kinase signaling. Moreover, we demonstrate that increased expression of nSMase2 is sufficient to suppress phosphorylation of p70 S6 kinase, its downstream signaling, and its protein synthesis, thus identifying a novel mechanism by which Cer production can regulate cell growth. Because the mTOR-S6K pathway is often dysregulated in cancer and other pathologies, further studies aimed at dissecting the interactions between S6K signaling and sphingolipids may provide novel targets for therapeutic intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Lipidomics Core at the Medical University of South Carolina for the sphingolipid analysis performed and Rick Peppler at the Hollings Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Core facility for cell cycle analysis. We also thank Drs. Ashley Cowart, Nabil Matmati, and David Montefusco for critical reading of the manuscript and Dr. Jola Idkowiak-Baldys for helpful discussions. Special thanks to Tim Steppe at SA Biosciences for assistance in development of the sphingolipid array.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM 43825 (to Y. A. H.). This work was also supported by an American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship (to R. W. J.). Work conducted in the Lipidomics Core was supported by NIH grant C06 RR01882 from the extramural research program of the National Center for Research Resources.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Data.

N. Marchesini and Y. A. Hannun, unpublished observations.

C. J. Clarke, unpublished observations.

- Cer

- ceramide

- ATRA

- all-trans-retinoic acid

- CerS2

- ceramide synthase 2

- DEGS

- dihydroceramide desaturase

- N-SMase

- neutral sphingomyelinase

- PP2A

- protein phosphatase 2A

- S6K

- ribosomal S6 kinase

- SMase

- sphingomyelinase

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- GSK

- glycogen-synthase kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hannun Y. A., Obeid L. M. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu B. X., Clarke C. J., Hannun Y. A. (2010) Neuromolecular Med. 12, 320–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jenkins R. W., Canals D., Hannun Y. A. (2009) Cell Signal. 21, 836–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marchesini N., Osta W., Bielawski J., Luberto C., Obeid L. M., Hannun Y. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25101–25111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hayashi Y., Kiyono T., Fujita M., Ishibashi M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18082–18086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cho J. Y., Lee W. B., Kim H. J., Mi Woo K., Baek J. H., Choi J. Y., Hur C. H., Ryoo H. M. (2006) Gene 372, 71–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chae Y. M., Heo S. H., Kim J. Y., Lee J. M., Ryoo H. M., Cho J. Y. (2009) BMB Rep. 42, 86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ito H., Murakami M., Furuhata A., Gao S., Yoshida K., Sobue S., Hagiwara K., Takagi A., Kojima T., Suzuki M., Banno Y., Tanaka K., Tamiya-Koizumi K., Kyogashima M., Nozawa Y., Murate T. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1789, 681–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Conzen S. D. (2008) Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 2215–2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corlazzoli F., Rossetti S., Bistulfi G., Ren M., Sacchi N. (2009) PLoS One, 4, e4305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murakami M., Ito H., Hagiwara K., Yoshida K., Sobue S., Ichihara M., Takagi A., Kojima T., Tanaka K., Tamiya-Koizumi K., Kyogashima M., Suzuki M., Banno Y., Nozawa Y., Murate T. (2010) J. Neurochem. 112, 511–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sun W., Hu W., Xu R., Jin J., Szulc Z. M., Zhang G., Galadari S. H., Obeid L. M., Mao C. (2009) FASEB J. 23, 656–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Murate T., Suzuki M., Hattori M., Takagi A., Kojima T., Tanizawa T., Asano H., Hotta T., Saito H., Yoshida S., Tamiya-Koizumi K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9936–9943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kraveka J. M., Li L., Bielawski J., Obeid L. M., Ogretmen B. (2003) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 419, 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Somenzi G., Sala G., Rossetti S., Ren M., Ghidoni R., Sacchi N. (2007) PLoS One, 2, e836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parrott L. A., Templeton D. J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 24731–24736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peterson R. T., Desai B. N., Hardwick J. S., Schreiber S. L. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 4438–4442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Karakashian A. A., Giltiay N. V., Smith G. M., Nikolova-Karakashian M. N. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 968–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bielawski J., Pierce J. S., Snider J., Rembiesa B., Szulc Z. M., Bielawska A. (2010) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 688, 46–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Leenheer A. P., Lambert W. E., Claeys I. (1982) J. Lipid Res. 23, 1362–1367 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ma X. M., Blenis J. (2009) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 307–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ruvinsky I., Meyuhas O. (2006) Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 342–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim D. H., Sarbassov D. D., Ali S. M., King J. E., Latek R. R., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Sabatini D. M. (2002) Cell 110, 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Navé B. T., Ouwens M., Withers D. J., Alessi D. R., Shepherd P. R. (1999) Biochem. J. 344, 427–431 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Soliman G. A., Acosta-Jaquez H. A., Dunlop E. A., Ekim B., Maj N. E., Tee A. R., Fingar D. C. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 7866–7879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Inoki K., Ouyang H., Zhu T., Lindvall C., Wang Y., Zhang X., Yang Q., Bennett C., Harada Y., Stankunas K., Wang C. Y., He X., MacDougald O. A., You M., Williams B. O., Guan K. L. (2006) Cell 126, 955–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ji C., Yang B., Yang Y. L., He S. H., Miao D. S., He L., Bi Z. G. (2010) Oncogene 29, 6557–6568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lin C. F., Chen C. L., Chiang C. W., Jan M. S., Huang W. C., Lin Y. S. (2007) J. Cell Sci. 120, 2935–2943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shaw R. J., Kosmatka M., Bardeesy N., Hurley R. L., Witters L. A., DePinho R. A., Cantley L. C. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 3329–3335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cross D. A., Alessi D. R., Cohen P., Andjelkovich M., Hemmings B. A. (1995) Nature 378, 785–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lal L., Li Y., Smith J., Sassano A., Uddin S., Parmar S., Tallman M. S., Minucci S., Hay N., Platanias L. C. (2005) Blood 105, 1669–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dowling R. J., Zakikhani M., Fantus I. G., Pollak M., Sonenberg N. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 10804–10812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guertin D. A., Sabatini D. M. (2007) Cancer Cell 12, 9–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim W. J., Okimoto R. A., Purton L. E., Goodwin M., Haserlat S. M., Dayyani F., Sweetser D. A., McClatchey A. I., Bernard O. A., Look A. T., Bell D. W., Scadden D. T., Haber D. A. (2008) Blood 111, 4716–4722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Demircan B., Dyer L. M., Gerace M., Lobenhofer E. K., Robertson K. D., Brown K. D. (2009) Genes Chromosomes Cancer 48, 83–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marchesini N., Jones J. A., Hannun Y. A. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 1418–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang Q., Lee D., Sysounthone V., Chandraratna R. A. S., Christakos S., Korah R., Wieder R. (2001) Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 67, 157–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mazars P., Barboule N., Baldin V., Vidal S., Ducommun B., Valette A. (1995) FEBS Lett. 362, 295–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wu B. X., Zeidan Y. H., Hannun Y. A. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 730–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Taha T. A., Kitatani K., El-Alwani M., Bielawski J., Hannun Y. A., Obeid L. M. (2006) FASEB J. 20, 482–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Adams S. L., Cohen A. J., Lassová L. (2007) J. Cell. Physiol. 213, 635–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stoffel W., Jenke B., Blöck B., Zumbansen M., Koebke J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 4554–4559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aubin I., Adams C. P., Opsahl S., Septier D., Bishop C. E., Auge N., Salvayre R., Negre-Salvayre A., Goldberg M., Guénet J. L., Poirier C. (2005) Nat. Genet. 37, 803–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.