Abstract

The N-terminal regions of AAA-ATPases (ATPase associated with various cellular activities) often contain a domain that defines the distinct functions of the enzymes, such as substrate specificity and subcellular localization. As described herein, we have determined the solution structure of an N-terminal unique domain isolated from nuclear valosin-containing protein (VCP)-like protein 2 (NVL2UD). NVL2UD contains three α helices with an organization resembling that of a winged helix motif, whereas a pair of β-strands is missing. The structure is unique and distinct from those of other known type II AAA-ATPases, such as VCP. Consequently, we identified nucleolin from a HeLa cell extract as a binding partner of this domain. Nucleolin contains a long (∼300 amino acids) intrinsically unstructured region, followed by the four tandem RNA recognition motifs and the C-terminal glycine/arginine-rich domain. Binding analyses revealed that NVL2UD potentially binds to any of the combinations of two successive RNA binding domains in the presence of RNA. Furthermore, NVL2UD has a characteristic loop, in which the key basic residues RRKR are exposed to the solvent at the edge of the molecule. The mutation study showed that these residues are necessary and sufficient for nucleolin-RNA complex binding as well as nucleolar localization. Based on the observations presented above, we propose that NVL2 serves as an unfoldase for the nucleolin-RNA complex. As inferred from its RNA dependence and its ATPase activity, NVL2 might facilitate the dissociation and recycling of nucleolin, thereby promoting efficient ribosome biogenesis.

Keywords: ATPases, NMR, Nucleolus, Ribosome Assembly, RNA-binding Protein

Introduction

Nuclear valosin-containing protein (VCP)2-like protein (NVL) was first identified as a gene product that displays a high level of amino acid similarity with an AAA-ATPase, VCP/p97. AAA-ATPases, associated with various cellular activities, are hexameric ATP-hydrolyzing enzymes found in all three kingdoms of life. They play important roles in various cellular processes, including the dissociation of protein complexes and protein translocation (1–4). The AAA-ATPases are characterized by the presence of one (type I) or two (type II) copies of a well conserved catalytic ATPase domain comprising 220–250 amino acids. NVL is classified as a type II AAA-ATPase with two tandem AAA domains. In fact, NVL has two alternatively spliced isoforms, a short form, NVL1, and a long form, NVL2, which are produced from different methionines as the translation initiation sites (Fig. 1) (5). NVL2 resides in the nucleolus, where it is involved in the biogenesis of the 60 S ribosomal subunit. In this pathway, the ribosomal subunit RPL5 and the DNA helicase DOB1 have been identified as NVL2-binding proteins (6, 7). Other well known NVL orthologs include smallminded (smid), a Drosophila ortholog (7, 8); a CED-4-interacting protein, Mac-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans ortholog (9); and a more distant Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog, Rix7p (10, 11). The cellular roles of these nonvertebrate NVL orthologs are only partially consistent with each other. Consequently, further analysis of this molecule from a structural viewpoint is needed.

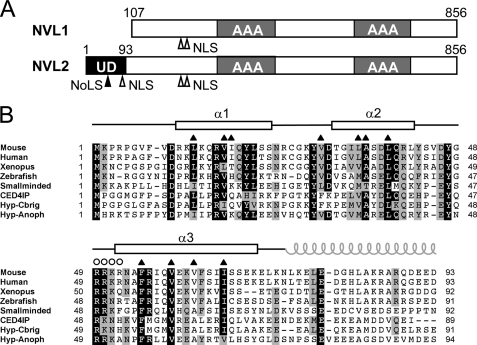

FIGURE 1.

Domain architecture of NVL and multiple sequence alignment of the NVL2UD. A, domain arrangement of NVL1 and NVL2. Two splicing variants of human NVL are shown. The translation of NVL1 starts at the second methionine of NVL2. The unique domain is isolated from the N-terminal region specific for NVL2. The filled arrowhead and open arrowheads indicate NoLS and NLS, respectively. UD, NVL2 unique domain; AAA, AAA domain. B, multiple sequence alignment of NVL2 orthologs. The secondary structure elements of NVL2UD(1–74) are shown at the top of the diagram with open boxes (α-helix). The residues in the hydrophobic core and the NoLS are indicated by triangles and circles, respectively. The gray spiral represents the coiled-coil region. Protein names and UniProtKB accession numbers are as follows: mouse (Q9DBY8), human (O15381), Xenopus (Q7ZXI4), zebrafish (P91638), smallminded (P91638), CED4IP (C. elegans; Q9U8KO), Hyp-Cbrig (Caenorhabditis briggsae; A8XYN0), and Hyp-anoph (Anopheles; Q7Q5U3). The sequence alignment was generated using ClustalX (70).

Despite the sequence similarity between VCP/p97 and NVL in their AAA regions, the N-terminal regions of NVL2 (NVL2UD) and VCP/p97 are different. The two proteins reside in different subcellular locations; VCP/p97 is in the cytoplasm, nucleus, and endoplasmic reticulum membrane, whereas NVL is exclusively localized in the nucleolus (5, 6). The amino acid sequences of the N-terminal regions are variable, in contrast to the high sequence conservation of the AAA domains. The N-terminal regions of the AAA-ATPases are generally considered to contain a domain that is responsible for the specific role of the enzymes, such as adaptor binding, substrate specificity, or localization. The NVL2UD has a nucleolar localization signal (NoLS) that is responsible for nucleolar targeting. Nagahama et al. (6) reported three separate regions as the nuclear and/or nucleolar localizing signals. Two of them exist in NVL2UD. A stretch of basic amino acids, such as arginine and lysine, reportedly contributes to the nucleolar accumulation of proteins (12). Based on the nucleolar targeting sequences from several proteins, a simple motif, (R/K)(R/K)X(R/K), was proposed (13). The NoLS of NVL2 (residues 49–52) matches this classic definition.

The nucleolus comprises a high density complex of ribosomal DNA, ribosomal RNA, and its precursors, as well as many proteins. The primary physiological function of the nucleolus is ribosome biogenesis (14). However, recent studies revealed that the nucleolus plays other important roles in maintaining cellular viability, including RNA processing, specific mRNA stabilization, cell cycle control, and assembly of RNA viruses; for these reasons, it is implicated in cancer and other diseases (15–20). The nucleolus is organized and/or maintained using a network of protein-protein and protein-RNA/DNA interactions (21). Among the nucleolus interactome, two proteins, nucleolin and nucleophosmin, are considered as the key hub molecules. When each protein was knocked out or knocked down, the function as well as the structure of the nucleolus collapsed (22–24). Interactions with these hub proteins through the NoLS might direct the proteins to the nucleolus. Nevertheless, recently, the definition of the NoLS has become more complex, because many sequences that do not match the classic NoLS motif have been reported (reviewed in Ref. 21). The divergent NoLS sequences are considered to use a variety of pathways to target proteins to the nucleolus. It is proposed that the key action of the NoLS is to be recognized by one or more of the nucleolar resident proteins (21). Consequently, the mechanism-based classification of the NoLS has become important in this field.

The purpose of this study is to clarify the mechanism of the subcellular localization of NVL2 by a structural analysis of the N-terminal region of NVL2. Using a bioinformatics approach combined with a high throughput protein expression study, we isolated an “NMR-ready” domain (NVL2UD, residues 1–74) from the N-terminal unique region of NVL2 (Fig. 1A) (25) and determined its three-dimensional structure using NMR. The solution NMR study revealed that the structure of NVL2UD adopted part of the winged helix motif. The nucleolar localization signal is exposed on the molecular surface. We also confirmed that the domain solely exhibits the nucleolar localizing activity. Additionally, we identified the nucleolin C-terminal fragment as a binding target of NVL2UD from HeLa cell extracts. The key residues responsible for nucleolar localization were identical to those for nucleolin binding. Finally, based on the “reversed” structural proteomics approach, we propose a physiological function for NVL2 in the nucleolus.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

DNA oligonucleotide primers were obtained from Hokkaido System Science Co. Ltd. (Sapporo, Japan). The anti-nucleolin antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA) and Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Other chemicals were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd. (Osaka, Japan) and Nacalai Tesque, Inc. (Kyoto, Japan).

Protein Techniques

The expression and purification of the N-terminal unique domains from mice were described previously (25). We used the GST fusion forms of NVL2UD for biochemical assays. The proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3), purified by chromatography on DEAE-Sepharose followed by glutathione-Sepharose affinity resin (GE Healthcare), and then dialyzed. We constructed plasmids for expressing GFP-tagged NVL2UD(1–74) and NVL2UD(1–74)AA in mammalian cells using the pcDNA-GFP-PRESAT vector, a pcDNA3.1-based vector containing the enhanced GFP gene with the PRESAT vector cloning site,3 according to the modified protocol (26). We also constructed plasmids for expressing His6-tagged human nucleolin fragments, R1234G (containing RRM domains 1–4 and the GAR domain (residues 286–710)), R123 (residues 286–560), R12 (residues 286–468), R23 (residues 391–560), R34 (residues 478–652), R34G (residues 478–710), R4G (residues 565–710), and R1 (residues 286–390), using the pET-His6-PRESAT vector according to the reported method (27). The proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3).

NMR Structure Analysis

The preparation of isotopically labeled NMR samples of NVL2UD was described previously (25). The NMR experiments and following structural determination are described in the supplemental material.

Cell Lines

We used HeLa and HEK293 cells in all experiments. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 units/ml streptomycin, and were incubated in humidified CO2 containing (5%) air at 37 °C.

Mass Spectrometric Identification of the Proteins That Bind to NVL2UD

Roughly 107 cells were collected, washed with PBS, and suspended in 200 μl of buffer containing 17.5 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 55 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm EGTA, 1 mm DTT, 0.25 mm PMSF, 0.05% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors (0.2 μg/ml antipain, 0.2 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.1 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.08 μg/ml pepstatin). After incubation on ice, the cells were disrupted by sonication. The whole cell extract was incubated with 180 pmol of either GST-NVL2UD(1–93) or GST alone. Protein complexes were captured by glutathione-Sepharose. After washing three times, the resin was mixed with an equal volume of SDS loading dye. Protein complexes were resolved using SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. In-gel proteolytic digestion followed by electrospray ionization tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) analysis was done at the Integrated Center for Mass Spectrometry (Graduate School of Medicine, Kobe University) using a mass spectrometer (Q-TOF 2; Micromass, Manchester, UK). Protein identification was performed using Mascot (Matrix Science).

Western Blotting Analysis

The HeLa cells were collected, washed with PBS, and suspended in 25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm PMSF, and protease inhibitors. The cell extract was incubated with GST-NVL2UD(1–74) or GST alone. Protein complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a PVDF membrane. We detected the nucleolin fragments using the anti-nucleolin antibody (catalog no. sc-17826, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) followed by an HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody. The bands were visualized using a kit (ECL-Plus, GE Healthcare). An LAS-1000 detector (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan) was used for detection.

In Vitro Binding Assays

To assess the protein-protein interaction properties of NVL2UD and nucleolin C-terminal fragments, a GST pull-down assay was conducted. GST or GST-NVL2UD (140 pmol) was incubated with the E. coli cell lysate-expressed His6-tagged nucleolin fragments in a buffer containing 25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 120 mm KCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mm DTT, and protease inhibitors for 2 h at 4 °C and then immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose for 1 h. After three washes, an equal volume of SDS loading dye was added, and the proteins were fractionated by 12 or 15% SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The signal intensities were quantified by the ImageJ 1.40g program (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Fluorescent Microscopy

Cells were grown either on chamber slides (Matsunami Glass Ind. Ltd., Osaka, Japan), in normal 35-mm dishes, or on glass bottom 35-mm dishes (MatTek Corp.) to about 30% confluence. GFP-tagged-NVL2UD or enhanced GFP alone was transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 24 h of incubation, living cells were observed. For immunological staining, we washed the cells twice with PBS and fixed them with methanol for 20 min at −20 °C, washed them twice with PBS for 5 min, and then incubated them with the anti-nucleolin antibody in PBS supplemented with 5% skim milk overnight at 4 °C. The cells were then washed and incubated with a fluorescent secondary antibody (Cy3TM-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody, C2181 (Sigma)) in PBS supplemented with 5% skim milk for 60 min. The cells were washed and then incubated with DAPI (final concentration, 100 ng/ml) in PBS at 5 min. The cells were then mounted in Prolong Antifade mounting medium (Invitrogen). All images were obtained using fluorescence microscopy with a microscope equipped with a color CCD camera system (IX71 and DP-70, respectively; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

Structural Analysis of Mouse NVL2UD

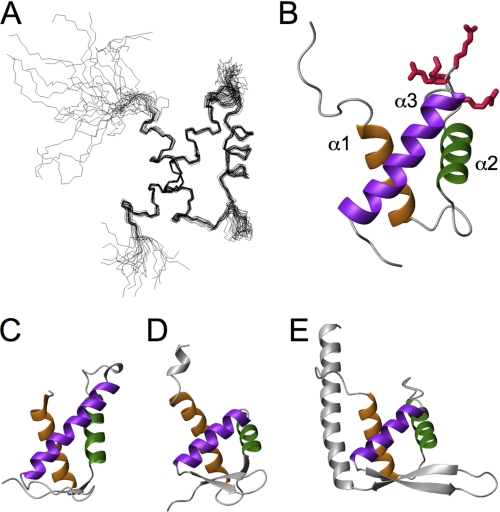

The final ensemble of the 20 lowest energy structures of NVL2UD(1–74) was generated from a total of 994 experimental constraints derived by NMR. A representative image is presented in Fig. 2B. Supplemental Table S1 and supplemental Fig. S1 show that the resulting structures satisfy the experimental constraints well. The stereochemical quality of the ensemble is good, with >91% of the backbone φ-ψ angles occupying the most favored or allowed regions in the Ramachandran plot (supplemental Table S1 and supplemental Fig. S1). Excluding the disordered regions that are the N- and C-terminal residues and parts of internal loops (residues 1–10 plus the extra four residues from the vector, residues 28, 49–51, and 71–74), the root mean square deviation values are 0.418 Å for the backbone heavy atoms and 1.035 Å for all heavy atoms. Based on the refined structure of NVL2UD, we conducted a multiple sequence alignment of the domains among the NVL orthologs, using a secondary structure-based penalty (Fig. 1B). Although the amino acid identities among these NVL homologs are not high (19–86%), the residues forming the hydrophobic core as well as the second loop connecting helices 2 and 3 are well conserved. Consequently, the N-terminal regions of the NVL2 homologs are novel structural domains with similar folds.

FIGURE 2.

Structure of NVL2UD. A, a superposition of the backbone atoms of the 20 lowest energy structures. B, ribbon diagram of NVL2UD, with the NoLS residues shown as sticks. C–E, the structural neighbors of NVL2UD. The Dali server was used to identify proteins structurally similar to NVL2UD. The corresponding helices are colored the same (helices 1, 2, and 3 are orange, green, and dark violet, respectively). C, DP2 (PDB code 1cf7). D, ADAR1 (PDB code 1qgp). E, replication terminator protein (PDB code 1f4k). All panels were prepared using MOLMOL (71).

NVL2UD(1–74) adopts an orthogonal three-helix fold, which consists of helix 1 (residues 11–23), helix 2 (residues 32–42), and helix 3 (residues 52–70) (Fig. 2A). A structural comparison of NVL2UD, using the DaliLite server (28), identified many proteins containing a winged helix domain with Z-scores higher than 4.5. For example, the structures of the DNA binding domain of a transcription factor, DP2 (PDB code 1cf7, Z-score 5.2), and the Zα domain of a double-stranded RNA deaminase I, ADAR1 (PDB code 1qgp, Z-score 4.5) and that of the 34L protein (PDB code 1sfu, Z-score 4.5) resembled the NVL2UD structure. In addition, the partial structures of cullin-1 (PDB code 1ldj, Z-score 4.8), FurB (PDB code 2o03, Z-score 4.7), replication terminator protein (PDB code 1f4k, Z-score 4.7), and NEDD8 (PDB code 3dqv, Z-score 4.6) were retrieved. The presence of this fold was not predicted by several structure prediction methods, including FUGUE (29) and FORTE (30). As described below, NVL2UD contains the NoLS. This motif resides in the second loop region, which is exposed to the solvent.

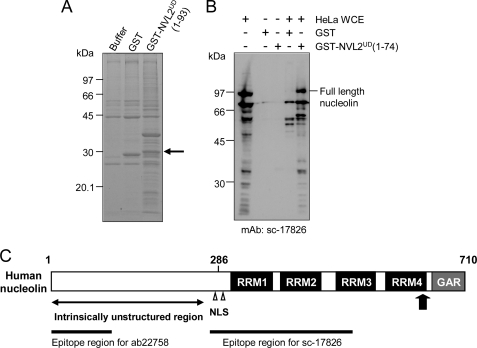

Identification of the Nucleolin C-terminal Fragment as the Binding Target of NVL2UD

To identify new NVL2UD-associated proteins, we performed an in vitro protein-binding experiment followed by an electrospray ionization-MS/MS analysis. We used HeLa whole cell extracts to identify the partner proteins associated with NVL2UD(1–93). The Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining of the affinity-captured proteins revealed several polypeptides that specifically co-purified with GST-NVL2UD (Fig. 3A). In comparison with the proteins associated with GST alone, we carefully examined a specifically enriched protein band at 30 kDa. The MS analysis revealed that most NVL2UD-binding proteins were related to RNA processing or the nucleolus (Table 1 and supplemental Table S2). It is particularly interesting that some potential NVL2UD-binding proteins harbor RRM domains, although none of these binding proteins has previously been reported to interact with NVL2. As shown in Table 1, nucleolin is the second candidate of the NVL2UD-binding partners. Nucleolin is an abundant protein in the nucleolus and is the putative NoLS receptor. Therefore, we further addressed this link between nucleolin and NVL2. A question remained as to the difference between the theoretical molecular mass of full-length nucleolin (Mr76,614) and that of the analyzed band (30 kDa). We confirmed the existence of full-length nucleolin in both the NVL2UD(1–74) and NVL2UD(1–93)-associated proteins, using a Western blot analysis (Fig. 3B and supplemental Fig. S2). We detected full-length nucleolin by two distinct antibodies, sc-17826 (epitope: 271–520) and ab22758 (epitope: 1–100). The full-length nucleolin showed a band at 95 kDa, probably because of phosphorylation. We detected several shorter nucleolin fragments with the sc-17826 antibody. The shorter fragments are attributed to the degradation of its unstructured N-terminal region during sample preparation. The N-terminal region contains proteolytic sites (31). The association of nucleolin with NVL2UD(1–74) and NVL2UD(1–93) was also detected using HEK293 cells, although the full-length nucleolin in the cell extract was more rapidly degraded than that in the HeLa cell extract, despite the use of increased amounts of the protease inhibitors (supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 3.

NVL2UD is a nucleolin binding domain. A, in vitro binding assay of GST-NVL2UD with a HeLa cell extract. GST-NVL2UD(1–93)-associated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The band indicated by an arrow was subjected to the MS/MS analysis. B, Western blot of HeLa proteins captured by GST-NVL2UD. GST or GST-NVL2UD(1–74) was incubated with either HeLa whole cell extract (WCE) or buffer, and co-purified proteins were electrophoresed. The proteins were blotted onto a PVDF membrane and then detected by an anti-nucleolin antibody. The epitope for the antibody is residues 271–520 of human nucleolin. C, domain architecture of human nucleolin. The arrow marks the position of the peptide sequence detected by the MS/MS analysis. The RRM domains and the GAR domain are shown as black and gray boxes, respectively, with the domain names.

TABLE 1.

List of protein candidates identified from mass spectrometric analysis

| Protein | Molecular mass | Scorea |

|---|---|---|

| kDa | ||

| Ribosomal protein L7 | 29.7 | 113 |

| Nucleolin | 76.6 | 86 |

| Leucine-rich repeat-containing 59 | 34.5 | 83 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C | 33.6 | 80 |

| Progesterone receptor membrane component 2 | 23.8 | 78 |

| Proteasome subunit α type 5 | 26.4 | 75 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D | 30.4 | 70 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A | 37.0 | 68 |

| Proteasome subunit α type 7 | 27.9 | 63 |

| Prohibitin | 23.6 | 62 |

| Vimentin | 20.0 | 62 |

a Score determined as −10 Log (P), where P is the probability that the observed match is a random event, calculated by the program MASCOT. A score >54 indicates extensive homology, p < 0.05.

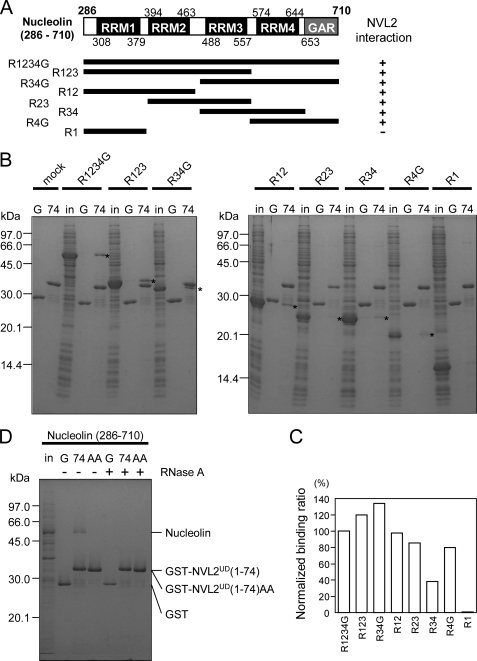

NVL2UD Potentially Binds to Two or More Successive RNA Binding Domains of Nucleolin

Human nucleolin contains 710 amino acids. It is divided roughly into three regions: N-terminal, central, and C-terminal domains. The N-terminal domain is rich in acidic residues and is predicted as natively disordered. The central domain contains four repeats of RRM domains. The C-terminal GAR domain is rich in glycine and arginine. Both the RRM and GAR domains are RNA binding domains (32). Because the peptide sequence detected by the MS/MS analysis corresponded to the C terminus of the fourth RRM domain (Fig. 3C), we prepared the recombinant nucleolin, R1234G (residues 286–710, containing the four RRM and the C-terminal GAR domains), and examined its interaction with NVL2UD. The R1234G interacted with NVL2UD specifically, thus suggesting that this region of nucleolin was sufficient for NVL2UD binding (Fig. 4, A and B).

FIGURE 4.

Interaction between NVL2UD and nucleolin. A, summary of the binding assays between NVL2UD and various nucleolin fragments. B, in vitro binding assay with nucleolin fragments. Either GST (G) or GST-NVL2UD(1–74) (74) was incubated with E. coli cell lysates expressing various nucleolin fragments (in). The bound proteins were pulled down and separated using 15% SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Asterisks denote the nucleolin fragments bound to NVL2UD(1–74). C, quantification of the nucleolin fragments bound to GST-NVL2UD(1–74). The signals corresponding to the nucleolin fragments in B were integrated and normalized by their molecular weights, using ImageJ. D, RNA is involved in the NVL2-nucleolin complex. An in vitro binding assay was conducted with nucleolin (R1234G) and wild-type or mutant NVL2UD(1–74) in the presence or absence of RNase A.

To define the minimum region responsible for NVL2UD binding by nucleolin, we expressed several fragments of nucleolin in E. coli and examined their NVL2UD binding ability. Almost all of the fragments (R123, R34G, R12, R23, R34, and R4G) except for R1 retained affinity for NVL2UD (Fig. 4, B and C). In detail, R123 and R34G showed higher affinity than the others, and R34 showed the lowest affinity. Because the sequence identity among the four RRMs is not high (20–38%), it is unlikely that NVL2UD recognizes a certain common motif or surface among the four RRM domains (supplemental Fig. S3). We propose another mechanism, in which two or more successive RNA binding domains (RRM and GAR) are responsible for NVL2UD binding with promiscuous recognition. Additionally, we expected that the interaction between NVL2UD and nucleolin is not accomplished by simple protein-protein binding. We examined whether the purified R12 interacted with NVL2UD, using NMR titration experiments with R12 and 15N-labeled NVL2UD (supplemental Fig. S4). No significant chemical shift perturbations were observed, suggesting the involvement of additional factors for their interaction.

RNA Enhances the Interaction between NVL2UD and Nucleolin

According to the unusual observation described above, we examined the effect of RNA on the nucleolin-NVL interaction. The nucleolus contains highly condensed RNAs, especially preribosomal RNA, and thus RNA could affect the interaction between NVL2UD and nucleolin. To test this possibility, we added RNase A to the pull-down assay, and the specific interaction disappeared (Fig. 4D). This result revealed that RNA is necessary for the NVL2-nucleolin interaction. Therefore, NVL2UD might bind to the nucleolin-RNA complex in which more than two successive RNA binding domains hold the RNA.

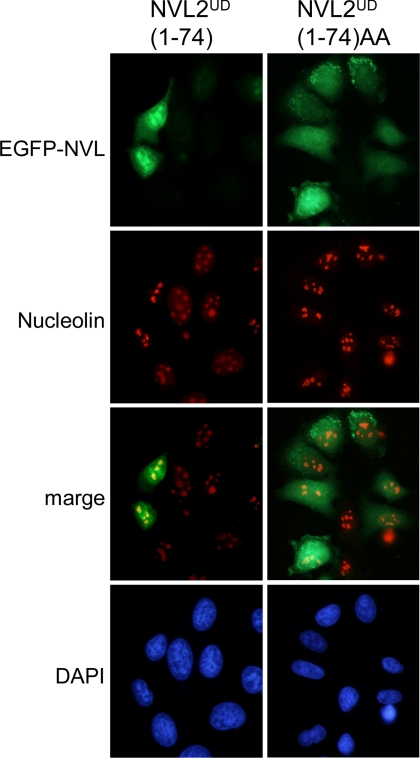

The RRKR Motif in NVL2UD Is Necessary and Sufficient for Nucleolar Targeting

In fact, NVL2UD contains the classic NoLS consensus, (R/K)(R/K)X(R/K), at residues 49–52. When the RRKR motif was substituted to RRAA, the nucleolar accumulation of NVL2 was lost (6). To examine whether these residues contribute to the RNA-mediated NVL2-nucleolin interaction, we used the NVL2UD RRAA mutant (NVL2UDAA) (Fig. 4D). The NVL2UDAA could not interact with nucleolin, irrespective of the presence of RNA. Next, to examine the relationship between the nucleolin-NVL2UD interaction and the nucleolar localization of NVL2UD, we compared the cellular localizations of NVL2UD and NVL2UDAA. Whereas NVL2UD accumulated in the nucleus and mainly in nucleoli, almost all of the NVL2UDAA remained in the cytoplasm and did not localize to the nucleolus (Fig. 5). These results demonstrated that NVL2UD is an isolated domain sufficient for the nucleolar localization of NVL2 and that the nucleolar localization of NVL2UD requires its interaction with the nucleolin-RNA complex.

FIGURE 5.

NVL2UD is a nucleolus localization domain. HeLa cells were transfected with GFP-NVL2UD(1–74) or GFP-NVL2UD(1–74)AA. After a 24-h incubation, cells were fixed, stained with anti-nucleolin antibody and DAPI, and then visualized.

DISCUSSION

Nucleolar Localization Motif within NVL2UD

We identified NVL2UD, a small globular domain, which contains a “classic” nucleolar localization signal consensus sequence, (R/K)(R/K)X(R/K), in its structured region. Recent studies have shown that the classic description of nucleolar localization signals must be changed and expanded drastically. This results from the complex pathway of the nucleolar localization of proteins, in contrast to the nuclear localization signal (NLS), which encodes the recognition sequence of the dominant NLS receptors, importins. To date, no common NoLS signal recognition molecule has been identified, unlike the importins and exportins for NLS and nuclear export signal. Instead, many proteins involved in the nucleolar protein-protein interaction network is responsible for nucleolar localization (21). Our results revealed that the RRKR motif in NVL2UD plays a role in both nucleolar targeting and retention. The association with the nucleolin-RNA complex might contribute to the nucleolar retention of NVL2. This supports the network model for nucleolar localization.

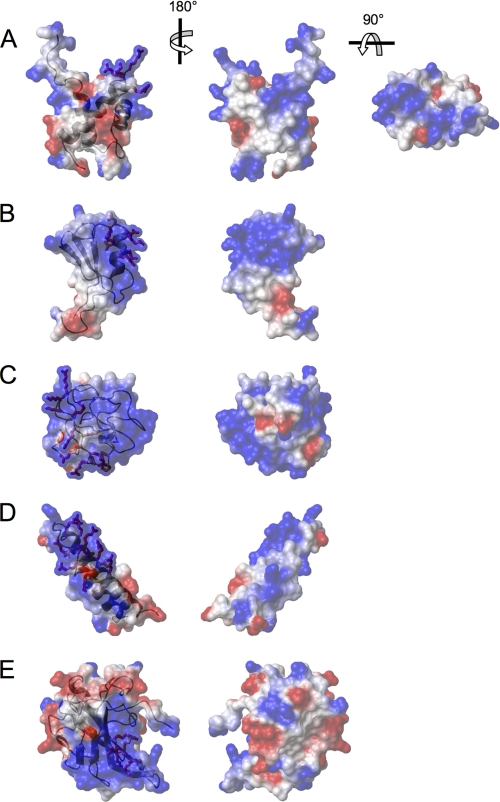

From this viewpoint, we tried to identify a structural consensus of the NoLS, by comparing the structure and the surface properties of NVL2UD with other known NoLS-containing structures. We chose the representative NoLSs from the recent nucleolar targeting review by Emmott and Hiscox (21). Among them, we found six unique structures in the Protein Data Bank with the following PDB codes: 1k5k (HIV-1 Tat), 1etf (HIV-1 Rev peptide-RNA), 2bxx (IBV-N protein), 2hdp (MDM2), 2fgf (FGF2), and 2ang (angiogenin). These proteins, except for FGF2 and angiogenin, interact with many of the major nucleolar components: nucleolin, nucleophosmin, and RNA. HIV-1 Tat and HIV-1 Rev interact with either nucleophosmin or RNA directly through the NoLS, and the solution structure of the HIV-1 Rev peptide-RNA complex was solved (33–37). Nucleophosmin also plays an important role in its interaction with MDM2 (38). Regarding MDM2, its C-terminal ring finger domain, containing the NoLS as well as the N-terminal region, is responsible for nucleophosmin binding. On the other hand, RNA binds to the extended RNA binding site containing the NoLS of IBV-N protein (39). Among them, MDM2 and IBV-N protein reportedly interact with nucleolin (40, 41). A positively charged cluster covers most of the surfaces of these molecules (Fig. 6), suggesting that charge-charge interactions are important for nucleolar localization. Moreover, most of the arginines and lysines in the NoLS, the key residues for nucleolar localization, are exposed on the edge of the molecule. The NoLS of NVL2UD forms a positively charged protrusion at the top edge of the domain; however, the charge distribution is unique, in that the positively charged clusters are separately positioned. Interestingly, HIV-1 Tat and Rev have exposed side chains with RNA recognizing arginines and lysines, which are suitable for base interactions with structured RNA. The NoLS of NVL2UD adopts a similar exposed conformation, thereby suggesting the affinity for RNA. Although the direct contribution of the NoLSs to their nucleolin binding was not examined for MDM2 and IBV-N protein, the NoLS of MDM2 forms the prominent protrusion at the top of the convex surface of the positive cluster. We presume that MDM2 interacts with nucleolin in a manner similar to NVL2UD. To our knowledge, NVL2UD is the first domain found to be responsible for nucleolar localization through an interaction with the nucleolin RRM domains.

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of NoLS structures with the NVL2UD. Shown are NoLS-containing structures selected from the list of Emmott and Hiscox (21). The electrostatic surface representations are superimposed on the ribbon diagrams. Positive (blue) and negative (red) electrostatic potentials of each molecule are mapped on the van der Waals surfaces. NoLSs are depicted as sticks and are colored red (Arg and Lys) or orange (all residues except Arg and Lys). A, NVL2UD (PDB code 2rre); B, MDM2 ring finger domain (PDB code 2hdp); C, HIV-1 Tat (PDB code 1k5k); D, HIV-1 Rev (PDB code 2x7l); E, IBV-N protein (PDB code 2bxx).

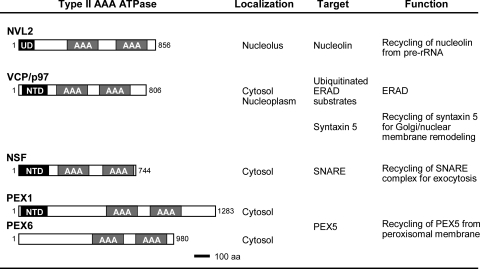

Molecular Architecture of NVL Compared with Other Type II AAA-ATPases; Classification with Type II AAA-ATPases

Fig. 7 presents a summary of the similarities and the differences of the type II AAA-ATPases, with their domain architectures. For the conserved NTDs of the other type II AAA-ATPases, extensive structural-functional studies of NSF (42–47), VCP (p97) (48–55), and PEX1 have been reported (56–58). NSF and its yeast ortholog, Sec18, are responsible for heterotypic membrane fusion mainly in exocytic pathways (46–48). The α-, β-, and γ-soluble NSF attachment proteins are the most important targets of NSF (42). VCP and yeast CDC48 are involved in endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation (49–51) as well as in remodeling of the Golgi and nuclear membrane (48, 52). Although the specific targets of the VCP and CDC48 unfoldase activities remain unclear, they have various cellular functions involving many different adaptor and anchor molecules, such as p37 (59), p47 (52), Ufd1/Npl4 (51), VCIP135 (53), Derlin-1, and VIMP (54). These different VCP adaptors might control VCP functions. Actually, PEX1 has a slightly different domain architecture, with the common NTD, followed by a unique insertion of ∼300 residues, and the AAA domains (D1 and D2). Although the NTD of PEX6 has not been determined, the FORTE structure prediction server revealed a high Z-score for the homologue to PEX1NTD.4

FIGURE 7.

Summary of the type II AAA-ATPases. Domain architecture, subcellular localization, target proteins, and functions of type II AAA-ATPases are indicated. Each AAA-ATPase dissociates the target from the protein complex. Because the removed proteins are used again in the following assembly cycle for the respective complex, we propose that the recycling of target proteins is a function of the type II AAA-ATPases.

This figure clearly shows that NVL (and its orthologs) are structurally distinct from the other type II AAA-ATPases. For example, NVL only works at the nucleolus and not on the surface of the membranous organelle. The smaller NTD (NVL2UD) and insertion lengths between the domains are characteristic. Moreover, NVL2UD can be eliminated by alternative splicing. Nevertheless, some common features with these type II AAA-ATPases are still visible. In general, all of these enzymes form a hexameric ring and can act as protein unfoldases. Most of the type II AAA-ATPases are located in organelle membranes, where they are involved in specific functions, such as membrane fusion (42, 43, 48) and protein transport across the membrane (49, 60–62). The process of protein-protein and/or protein-membrane association is self-driving and thereby ATP-independent. In contrast, the reversal processes, in which protein-protein/protein-lipid interactions are dissociated, often require ATP energy generated by AAA-ATPases. These reversal processes are necessary for the next cycle of the complex formation for many biological events, such as membrane fusion and peroxisomal protein transport. Consequently, the common feature of the known type II AAA-ATPases is to reuse and/or to recycle the molecular machinery.

Role of NVL in the Nucleolus

In contrast to the other membrane-related AAA-ATPases, we found that NVL2UD functions through a nucleolin-RNA complex at nucleoli. Nucleolin is a hub protein of the network of multiple protein-protein interactions in the nucleolus, which preserves the nucleolus structure. Nucleolin harbors a long, natively disordered region with a cluster of acidic amino acids, which might serve as a scaffold for many nucleolin-binding proteins (21). Recent studies have shown that intrinsically unstructured proteins and regions play key roles in protein-protein interaction networks, especially in the hub proteins in many interactomes (63, 64). Nevertheless, the results of the present study showed that NVL2UD binds to the RNA binding regions of nucleolin in an RNA-dependent manner but not to the intrinsically unstructured region. This feature distinguishes the role of NVL2 from those of the other nucleolin-binding proteins, such as topoisomerase I and histone H1. As mentioned above, the conserved NTDs of the other type II AAA-ATPases, except for NVL, are involved in binding to either adaptor proteins or substrates. Similarly, nucleolin may be the NVL2 adaptor that NVL2 works with or one of the NVL2 substrates.

If nucleolin is the NVL2 adaptor, then the ATP-hydrolyzing energy of NVL2 is transferred to nucleolin. It then promotes dissociation of the protein-protein interaction between the disordered region and the nucleolin partner proteins. Although the nucleolar resident proteins drastically alter their members, according to the cell cycle and extracellular stimuli (17), the mechanism of this dynamic nucleolar remodeling has remained unclear. Therefore, we propose NVL2 as one candidate for the master molecule of nucleolar functions. On the other hand, the latter case, in which nucleolin is the direct substrate of the NVL2 ATPase activity and NVL2 promotes nucleolin dissociation from its target RNAs, is also likely.

Our results suggest that NVL2UD can act on any pair of successive RRM domains in the presence of RNA rather than on one particular RRM domain. In other words, the RRMs and the following GAR domain seem to act redundantly for NVL2UD binding, as presumed by the different molecular surfaces of the four RRMs. For example, the conserved surface residues of the RRMs are no greater than 20%, as deduced by comparing their solution structures (PDB codes 2rkk, 2fc9, and 2fc8, respectively) (65).5 Moreover, the locations of the identical residues differ among them. This surface variation results in the different specificity to RNA. For example, the first and second RRM domain pairs are tightly bound to the specific stem-loop RNA (rGGCCGAAAUCCCGAAGUAGGCC) in the complex structure (66). This RNA merely interacts with the third and fourth RRM domains (67). Nevertheless, these four RRMs were functionally redundant in vivo, especially for RNA processing during ribosome biogenesis, although the efficiency of the RNA processing was different (68). Taken together, we concluded that NVL2UD recognizes the nucleolin-RNA complex in a promiscuous manner, which is not dependent on either a specific protein-protein interaction or a specific RNA sequence. It is more likely that the target of NVL2UD is a certain structural element, such as a looped out RNA between two successive RNA binding domains of nucleolin. This idea arises from the mechanism of the HIV-Tat-RNA interaction, in which the peptide also acts as a nucleolar localization signal sequence for HIV-Tat. In that case, two arginine residues in the basic peptide promote tight binding of Tat to the RNA stem loop, with an interaction termed the “arginine fork” (69). We hypothesize that the mechanism of nucleolin interaction by NVL2UD resembles that of HIV-Tat, in which the side chains of the RRKR motif grasp the RNA loops formed by nucleolin RNA binding domains. We showed that the RNA mixture of unknown sequences, which is eventually contaminated from E. coli extract, enhanced the NVL2UD-nucleolin interaction. Additional work is necessary to clarify the molecular basis of NVL2UD recognition of the nucleolin-RNA complex.

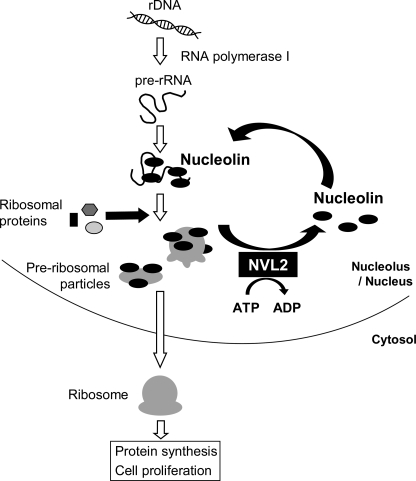

Proteins containing RRM domains reportedly interact with their specific RNA sequences. It is assumed that nucleolin binds to its unique binding motifs, which are included in preribosomal RNA. The affinity between nucleolin and the target RNA is increased by the simultaneous interaction of successive RNA binding domains. Therefore, the existence of an active mechanism to release nucleolin from RNAs is favorable. Indeed, this theory is supported by the observation that the dominant negative NVL2 mutant suppresses 60 S ribosomal subunit biogenesis (6). A possible mechanism of ribosome biogenesis control by NVL2 is shown in Fig. 8.

FIGURE 8.

Model for the function of NVL2 in ribosome biogenesis. In ribosome biogenesis, nucleolin plays a role in rDNA transcription and maturation. Nucleolin binds to rRNA via its RRM domains, and it may regulate ribosome maturation. NVL might dissociate the nucleolin RRM domains from the rRNA with energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to promote some steps, such as protein incorporation or rRNA folding. The released nucleolin interacts with other rRNA molecules as well as rDNA. Consequently, NVL recycles nucleolin at the nucleolus.

In conclusion, we solved the structure of the N-terminal unique domain of NVL2. We identified nucleolin as a new target for NVL2. Our results showed that RNA enhances the interaction between NVL2UD and nucleolin, in which the NoLS of NVL2 played the key role for their interaction. In fact, NVL2UD recognized any two or more successive RNA binding domains of nucleolin. By analogy to the other type II AAA-ATPases, we propose that NVL dissociates the nucleolin-RNA complex to promote ribosome biogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. K. Tomii (National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology) for assisting with the FORTE data base search and Dr. N. Hatano (Integrated Center for Mass Spectrometry, Kobe University) for performing the MS/MS analysis.

This study was supported in part by the Japan Science and Technology Agency Institute for Bioinformatics Research and Development and by a grant-in-aid for scientific research on Innovative Areas. This work was also supported by Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (c) 22570118 from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (to H. H.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S4.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2rre) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The chemical shift assignments have been deposited in the BioMagResBank, under the accession code 11250 (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu).

N. Goda, T. Tenno, and H. Hiroaki, manuscript in preparation.

H. Hiroaki, K. Tomii, N. Goda, and H. Watabe, unpublished result.

S. Yokoyama, unpublished result.

- VCP

- valosin-containing protein

- AAA

- ATPases associated with various cellular activities

- NVL

- nuclear VCP-like protein

- NVL2UD

- nuclear VCP-like protein 2 unique domain

- NoLS

- nucleolar localization signal

- NTD

- N-terminal domain

- NSF

- N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein

- NLS

- nuclear localization signal

- RRM

- RNA recognition motif

- GAR

- glycine/arginine-rich

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lupas A. N., Martin J. (2002) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12, 746–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patel S., Latterich M. (1998) Trends Cell Biol. 8, 65–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neuwald A. F., Aravind L., Spouge J. L., Koonin E. V. (1999) Genome Res. 9, 27–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ogura T., Wilkinson A. J. (2001) Genes Cells 6, 575–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Germain-Lee E. L., Obie C., Valle D. (1997) Genomics 44, 22–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nagahama M., Hara Y., Seki A., Yamazoe T., Kawate Y., Shinohara T., Hatsuzawa K., Tani K., Tagaya M. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 5712–5723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Long A. R., Yang M., Kaiser K., Shepherd D. (1998) Gene 208, 191–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Long A. R., Wilkins J. C., Shepherd D. (1998) Mech. Dev. 76, 33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu D., Chen P. J., Chen S., Hu Y., Nuñez G., Ellis R. E. (1999) Development 126, 2021–2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kressler D., Roser D., Pertschy B., Hurt E. (2008) J. Cell Biol. 181, 935–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gadal O., Strauss D., Braspenning J., Hoepfner D., Petfalski E., Philippsen P., Tollervey D., Hurt E. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 3695–3704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Siomi H., Shida H., Nam S. H., Nosaka T., Maki M., Hatanaka M. (1988) Cell 55, 197–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weber J. D., Kuo M. L., Bothner B., DiGiammarino E. L., Kriwacki R. W., Roussel M. F., Sherr C. J. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 2517–2528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cmarko D., Smigova J., Minichova L., Popov A. (2008) Histol. Histopathol. 23, 1291–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Montanaro L., Treré D., Derenzini M. (2008) Am. J. Pathol. 173, 301–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Greco A. (2009) Rev. Med. Virol. 19, 201–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hernandez-Verdun D. (2006) Histochem. Cell Biol. 126, 135–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matthews D. A., Olson M. O. (2006) EMBO Rep. 7, 870–873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. David M. J., Martindill D. M., Riley P. R. (2008) Cell Cycle 7, 17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stark L. A., Taliansky M. (2009) EMBO Rep. 10, 35–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Emmott E., Hiscox J. A. (2009) EMBO Rep. 10, 231–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ugrinova I., Monier K., Ivaldi C., Thiry M., Storck S., Mongelard F., Bouvet P. (2007) BMC Mol. Biol. 8, 66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ma N., Matsunaga S., Takata H., Ono-Maniwa R., Uchiyama S., Fukui K. (2007) J. Cell Sci. 120, 2091–2105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Amin M. A., Matsunaga S., Uchiyama S., Fukui K. (2008) Biochem. J. 415, 345–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iwaya N., Goda N., Unzai S., Fujiwara K., Tanaka T., Tomii K., Tochio H., Shirakawa M., Hiroaki H. (2007) J. Biomol. NMR 37, 53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goda N., Tenno T., Takasu H., Hiroaki H., Shirakawa M. (2004) Protein Sci. 13, 652–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tenno T., Goda N., Tateishi Y., Tochio H., Mishima M., Hayashi H., Shirakawa M., Hiroaki H. (2004) Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 17, 305–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holm L., Rosenström P. (2010) Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shi J., Blundell T. L., Mizuguchi K. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 310, 243–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tomii K., Akiyama Y. (2004) Bioinformatics 20, 594–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pasternack M. S., Bleier K. J., McInerney T. N. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 14703–14708 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ghisolfi L., Kharrat A., Joseph G., Amalric F., Erard M. (1992) Eur. J. Biochem. 209, 541–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weeks K. M., Ampe C., Schultz S. C., Steitz T. A., Crothers D. M. (1990) Science 249, 1281–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li Y. P. (1997) J. Virol. 71, 4098–4102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tan R., Chen L., Buettner J. A., Hudson D., Frankel A. D. (1993) Cell 73, 1031–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Szebeni A., Herrera J. E., Olson M. O. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 8037–8042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Battiste J. L., Mao H., Rao N. S., Tan R., Muhandiram D. R., Kay L. E., Frankel A. D., Williamson J. R. (1996) Science 273, 1547–1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kurki S., Peltonen K., Latonen L., Kiviharju T. M., Ojala P. M., Meek D., Laiho M. (2004) Cancer Cell 5, 465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tan Y. W., Fang S., Fan H., Lescar J., Liu D. X. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 4816–4825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saxena A., Rorie C. J., Dimitrova D., Daniely Y., Borowiec J. A. (2006) Oncogene 25, 7274–7288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chen H., Wurm T., Britton P., Brooks G., Hiscox J. A. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 5233–5250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Clary D. O., Griff I. C., Rothman J. E. (1990) Cell 61, 709–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dalal S., Rosser M. F., Cyr D. M., Hanson P. I. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 637–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yu R. C., Jahn R., Brunger A. T. (1999) Mol. Cell 4, 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lenzen C. U., Steinmann D., Whiteheart S. W., Weis W. I. (1998) Cell 94, 525–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Whiteheart S. W., Kubalek E. W. (1995) Trends Cell Biol. 5, 64–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hay J. C., Scheller R. H. (1997) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9, 505–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rabouille C., Levine T. P., Peters J. M., Warren G. (1995) Cell 82, 905–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rabinovich E., Kerem A., Fröhlich K. U., Diamant N., Bar-Nun S. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 626–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ye Y., Meyer H. H., Rapoport T. A. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 162, 71–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Meyer H. H., Shorter J. G., Seemann J., Pappin D., Warren G. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 2181–2192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kondo H., Rabouille C., Newman R., Levine T. P., Pappin D., Freemont P., Warren G. (1997) Nature 388, 75–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Uchiyama K., Jokitalo E., Kano F., Murata M., Zhang X., Canas B., Newman R., Rabouille C., Pappin D., Freemont P., Kondo H. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 159, 855–866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ye Y., Shibata Y., Kikkert M., van Voorden S., Wiertz E., Rapoport T. A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14132–14138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang X., Shaw A., Bates P. A., Newman R. H., Gowen B., Orlova E., Gorman M. A., Kondo H., Dokurno P., Lally J., Leonard G., Meyer H., van Heel M., Freemont P. S. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 1473–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weller S., Gould S. J., Valle D. (2003) Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 4, 165–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shiozawa K., Maita N., Tomii K., Seto A., Goda N., Akiyama Y., Shimizu T., Shirakawa M., Hiroaki H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 50060–50068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shiozawa K., Goda N., Shimizu T., Mizuguchi K., Kondo N., Shimozawa N., Shirakawa M., Hiroaki H. (2006) FEBS J. 273, 4959–4971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Uchiyama K., Totsukawa G., Puhka M., Kaneko Y., Jokitalo E., Dreveny I., Beuron F., Zhang X., Freemont P., Kondo H. (2006) Dev. Cell 11, 803–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tamura S., Shimozawa N., Suzuki Y., Tsukamoto T., Osumi T., Fujiki Y. (1998) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 245, 883–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fujiki Y., Okumoto K., Otera H., Tamura S. (2000) Cell Biochem. Biophys. 32, 155–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fujiki Y., Miyata N., Matsumoto N., Tamura S. (2008) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36, 109–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Higurashi M., Ishida T., Kinoshita K. (2008) Protein Sci. 17, 72–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hegyi H., Schad E., Tompa P. (2007) BMC Struct. Biol. 7, 65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Arumugam S., Miller M. C., Maliekal J., Bates P. J., Trent J. O., Lane A. N. (2010) J. Biomol. NMR 47, 79–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Allain F. H., Bouvet P., Dieckmann T., Feigon J. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 6870–6881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Serin G., Joseph G., Ghisolfi L., Bauzan M., Erard M., Amalric F., Bouvet P. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 13109–13116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Storck S., Thiry M., Bouvet P. (2009) Biol. Cell 101, 153–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tao J., Frankel A. D. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 2723–2726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D. G. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Koradi R., Billeter M., Wüthrich K. (1996) J. Mol. Graph. 14, 51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.