Abstract

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity plays a pivotal role in antibody-based tumor therapies and is based on the recruitment of natural killer cells to antibody-bound tumor cells via binding of the Fcγ receptor III (CD16). Here we describe the generation of chimeric DNA aptamers that simultaneously bind to CD16α and c-Met, a receptor that is overexpressed in many tumors. By application of the systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) method, CD16α specific DNA aptamers were isolated that bound with high specificity and affinity (91 pm–195 nm) to their respective recombinant and cellularly expressed target proteins. Two optimized CD16α specific aptamers were coupled to each of two c-Met specific aptamers using different linkers. Bi-specific aptamers retained suitable binding properties and displayed simultaneous binding to both antigens. Moreover, they mediated cellular cytotoxicity dependent on aptamer and effector cell concentration. Displacement of a bi-specific aptamer from CD16α by competing antibody 3G8 reduced cytotoxicity and confirmed the proposed mode of action. These results represent the first gain of a tumor-effective function of two distinct oligonucleotides by linkage into a bi-specific aptamer mediating cellular cytotoxicity.

Keywords: Antibodies, Anticancer Drug, Cancer Therapy, Immunology, Nucleotide, ADCC, Aptamer, Bi-specific, Bivalent, Cancer

Introduction

Aptamers are structured single-stranded oligonucleotides that can bind to a large variety of targets with high affinity and specificity (1, 2). Aptamers can be isolated by an in vitro selection and an evolution process referred to as systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX)2 (3, 4). Because aptamers have the capacity to inhibit protein-protein interactions with potencies similar to those observed with antibodies, aptamers can also trigger inhibition signals, e.g. by blocking receptor multimerization, and consequently act as therapeutic antagonists. Reversely, bi- and multivalent aptamers can activate co-stimulatory receptors, e.g. to enhance T cell reactivity (5, 6). Finally, aptamers can be applied in ligand-based targeted therapies to specifically deliver cytotoxic payloads (7, 8) or siRNA (9) to tumor cells. Monoclonal antibodies serve as established and successful tumor therapeutics. However, naturally bivalent antibody formats comprise the risks of immunogenicity (10) and undesired activation by receptor dimerization (11). Development of monovalent therapeutic antibodies is elaborate and time-intensive (MetMAb (12)). Although antibodies exceed aptamers with proof as therapeutic molecules, high stability, and good pharmacokinetics, the potential advantages of aptamers are a rapid optimization, cost-effective and uniform synthesis, and a high probability of an absence of immunogenicity (5, 13). Approval of Macugen (pegaptanib sodium (14)) as the first therapeutic aptamer in 2007 as well as promising approaches in preclinical development and clinical trials (15, 16) only a few years after inception of the technology indicate aptamers as a promising new class of targeted therapeutics.

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC (17)) originating from the interaction of Fc fragments of antibodies with Fcγ receptors (FcγR) on natural killer (NK) cells plays a pivotal role in antibody-based tumor therapies (18, 19). NK cells are critical to host defense against invading organisms (20), are important for suppressing tumor metastasis and outgrowth (21), and can additionally stimulate components of the adaptive immune system to eliminate tumors (19, 22). ADCC, phagocytosis, and clearance of immune complexes by NK cells (23) are mediated by the intermediate affinity Fc receptor FcγRIIIα or CD16α (24). CD16α is expressed by NK cells, δγ-T cells, monocytes, and macrophages. The low affinity isoform FcγRIIIβ (CD16β) is highly related to CD16α and expressed on human neutrophils and eosinophils. Both isoforms can be proteolytically cleaved off cells (25, 26), but the prevalent soluble isoform is sCD16β (27). The CD16α polymorphism Phe-158 to Val-158 enhances its affinity for IgG1 and is associated with improved clinical outcome in tumor patients treated with therapeutical antibodies (28, 29). Several studies revealed ADCC as one major mode of action of antibody-based therapeutics (30, 31) and stimulated more interest in how to mobilize, expand, and activate NK cells in humans (32). So far, antibody effector functions such as recruitment of NK cells (33–35) or cytotoxic T cells (36) were successfully transferred to therapeutic, scFv-based bi-specific antibody strategies but could not be exploited in an aptamer format. Enabling NK cell recruitment to tumors by CD16α specific aptamers could combine the advantages of this molecule format with the potency of the tumor-effective function of ADCC (Fig. 1).

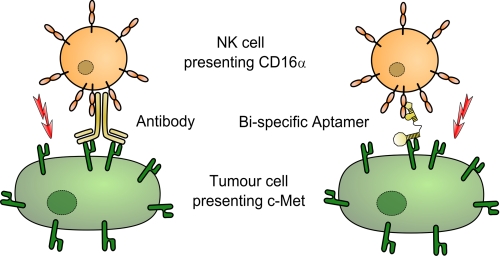

FIGURE 1.

Concept of bi-specific aptamers mediating tumor cell lysis. Bi-specific aptamers mimic ADCC by recruitment of natural killer cells via FcγRIIIα (CD16α) to c-Met-overexpressing tumor cells.

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are key regulators of critical cellular processes such as cell growth, differentiation, and tissue repair, but aberrant expression can contribute to the development and progression of cancer (37). In this study, the receptor tyrosine kinase hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGF-R or c-Met) was used as a tumor-associated antigen for specific targeting of tumor cells. c-Met is a multidomain receptor tyrosine kinase expressed on cells of epithelial origin (38, 39) and is essential for embryonic development (40) and wound healing. Aberrant c-Met signaling due to dysregulation of the receptor or overexpression of the natural ligand hepatocyte growth factor induces several biological responses that collectively give rise to invasive growth (37, 41, 42).

Specific recruitment of NK cells to c-Met-overexpressing tumors by a bi-specific aptamer simultaneously binding to c-Met and CD16α could induce ADCC and represent a suitable starting concept for the development of stable, nucleotide-based tumor therapeutics. High affinities to both CD16α alloforms Val-158 and Phe-158 in addition to high specificity to CD16α over the CD16β isoform could induce ADCC independent of allelic status or soluble CD16β decoy proteins. In addition, the monovalent tumor antigen binding architecture of the aptamers would enable inhibitory effects while per se excluding undesired c-Met activation. We herein present the first gain of a tumor-effective function of two distinct oligonucleotide entities by linkage into a bi-specific aptamer mediating tumor cell lysis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Aptamers and Target Proteins

Aptamers up to 100 bp in length were synthesized and PAGE-purified by Eurofins MWG Operon (Ebersberg, Germany), and longer and PEG-linked oligonucleotides were from Integrated DNA Technologies (Leuven, Belgium). Target proteins CD16α-6His, CD16β-10His, and c-Met-Fc were purchased at R&D Systems, and Fc-CD16α Val-158 and Phe-158 fusion proteins were kindly provided by Angela Lim (EMD Serono).

Aptamer Selection on Recombinant Protein

An ssDNA oligonucleotide library containing a 40-base random sequence flanked by primer regions on either end was used as a starting point for aptamer selection. The library sequence was 5′-GGAGGGAAAAGTTATCAGGC-(N)40-GATTAGTTTTGGAGTACTCGCTCC-3′, the forward primer was 5′-GGAGGGAAAAGTTATCAGGC-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-GGAGCGAGTACTCCAAAACTAAT-riboC-3′ (43). Aptamer amplification and precipitation were performed as described (81). Usage of a 3′-terminal ribo-dCTP reverse primer enabled alkaline-induced antisense strand break followed by Tris-borate-EDTA-PAGE strand separation (biostep gels). The respective ssDNA band was extracted with a scalpel, and aptamers were eluted for 18 h at 37 °C in 300 mm sodium acetate (Merck), 20 mm EDTA (Invitrogen) buffer, precipitated, and reconstituted in DPBS (Invitrogen).

Aptamer selection was based on the separation of target protein with bound aptamers on 0.5 m KOH-pretreated nitrocellulose filters (Whatman), whereas unbound aptamers were removed by washing. Selections were performed for 12 consecutive rounds at 37 °C in a 100-μl final volume DPBS for 1 h to obtain aptamers for use under physiological conditions. The first selection rounds were carried out with 1.6 μm aptamer library, 1 μm target protein, and 500-μl DPBS washing volume. From round 2 on, 1 μm pools were used with decreasing protein and increasing tRNA competitor concentrations (up to 1 mg/ml), two 1000-μl washing steps, negative filter selections (to remove filter binding sequences), and adequate counterselections at equal concentrations. Aptamers were eluted with preheated 7 m urea, 100 mm sodium acetate, 3 mm EDTA elution buffer. Precipitation, PCR amplification, reverse strand break, and PAGE purification (as above) yielded an enriched aptamer pool for further SELEX cycles. Pools of several rounds were cloned with a TOPO-TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) before sequencing of 96 clones per round (Eurofins MWG Operon). Sequences were grouped into aptamer families of 90% sequence identity using DNA Star SeqMan software. Structure prediction was obtained by the mfold software (44) set to salt concentrations as in DPBS and 37 °C.

Cell SELEX

Cell SELEX was initiated with 1 μm pools of CD16α DNA filter SELEX rounds 3 and 5 as pre-enriched starting libraries using alternating 2 × 107 recombinant CD16α Val-158- or Phe-158-positive Jurkat cells in a cross-selection, with decreasing cell amounts in later rounds. Counterselection was carried out from round 2 using CD16α-negative Jurkat E6.1 cells. Selections were performed at 37 °C, 300 rpm for 30 min in 200 μl of binding buffer (0.05% BSA in DPBS), and two 1-ml washing steps were implemented by centrifugation. Cell-bound aptamers were purified by phenol/chloroform extraction, and then amplified and analyzed as described above.

Dot Blot Affinity Determination

Affinities were determined essentially as described (81). Briefly, 5 fmol of radiolabeled aptamers were incubated with protein dilution series for 30 min at 37 °C in 30 μl of dot blot buffer (0.1 mg/ml tRNA, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, DPBS), and then aptamer-protein complexes were captured on a nitrocellulose filter (Schleicher and Schuell; pretreated as before), whereas unbound aptamers were immobilized on a PVDF Hybond P membrane (GE Healthcare; pretreated with methanol, water, and DPBS). Radioactivity was quantified using a Storm PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare). The percentage of aptamer bound was calculated using the formula: % of aptamer bound = 100 × (cpm of nitrocellulose/cpm of nitrocellulose + cpm of PVDF), and the background signal (aptamer bound to buffer only) was subtracted. Binding curves were plotted in Microsoft Excel, and KD values were calculated by non-linear fitting using XL fit (IDBS, Surrey, UK).

Flow Cytometry

Cellular binding was determined using a FACScan cytometer and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) as described (45). Briefly, 100 pmol of 3′-biotinylated aptamer or 10 μg of biotinylated reference antibody were used, and 1.5 × 104 events were detected via streptavidin-R-phycoerythrin conjugate (Sigma-Aldrich). All samples were incubated at 21 °C and 300 rpm due to temperature-dependent affinities of some aptamers (supplemental Fig. S7). Propidium iodide (Invitrogen) enabled dead cell exclusion by appropriate gating.

Bi-specific Aptamers and Linker Length Estimation

All aptamers were synthesized as one oligonucleotide chain and PAGE-purified. The nucleotide-to-nucleotide distance was averaged from the single-stranded portions of Protein Data Bank (PDB) entries 1HUT and 1OOA with PyMOL software (Schrödinger, LLC) to be 7 Å. Maximal putative linker lengths were calculated using this estimation.

Electrophoretic Motility Shift Assay

5 pmol of aptamer were incubated with 40 pmol of CD16α-6His and/or 15 pmol of c-Met-Fc in 10 μl of DPBS for 30 min at 37 °C. 2 μl of 6× DNA gel loading buffer (Novagen) were added, and the total volume was run on a water-cooled 4–20% Tris-borate-EDTA gel (biostep) followed by ethidium bromide staining (Invitrogen) and detection with a trans-illuminator (Alpha Innotech).

Serum Stability

10 pmol of gel-purified, radiolabeled oligonucleotides were incubated in PBS-buffered 90% FBS (Invitrogen), freshly prepared murine serum, or DPBS (Invitrogen) and analyzed as described (55). Half-life curve fitting was performed using the Origin software (OriginLab).

Cell Lines and Isolation of PBMC and NK Cells

Jurkat E6.1 (ATCC TIB 152) were cultured in RPMI 1640 + 2 mm glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (all Invitrogen). 100 nm methotrexate (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the culture medium of transfected Jurkat CD16α Val-158 or Phe-158 cells. GTL-16 cells were cultured in 10% FCS supplemented DMEM medium. MKN-45 cells (DMSZ ACC 409) were cultured as Jurkat cells but with 20% FCS, and EBC-1 cells (HSRRB JCRB0820) were cultured in minimal Eagle's medium (Sigma-Aldrich) with 2 mm glutamine and 10% FCS. All cells were kindly provided by Christa Burger, Merck Serono, and cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2, except for GTL-16 incubated at 10% CO2. PBMC were isolated by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation from peripheral blood from healthy donors (at Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) using Lymphoprep tubes (Axis-Shield) following the manufacturer's protocol. NK cells were further enriched by MACS using an NK cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer's instructions. All cells were used immediately after isolation.

ADCC Assay

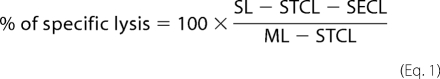

ADCC assays were performed for 4 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 at least in triplicate in a GAPDH release aCella-TOX assay (Cell Technology) using 104 target cells and PBMCs. Aptamer dilutions in RPMI 1640 with 10% ultralow IgG FCS (both Invitrogen) were measured at a constant PBMC:target cell ratio of 80:1. For blocking experiments, the CLN0020-competing monoclonal antibody 3G8 (BioLegend) was added at a 20-fold molar excess. Enzyme solutions were added as suggested by the manufacturer, and bioluminescence was immediately measured on a VarioSkan Flash luminometer (Thermo Scientific). Mean values of all references were calculated using Microsoft Excel, the “medium only” background signal was subtracted, and lysis was calculated using the formula

|

where SL = sample lysis; STCL = spontaneous target cell lysis; SECL = spontaneous effector cell lysis; and ML = maximal lysis.

RESULTS

Aptamer Selection and Characterization

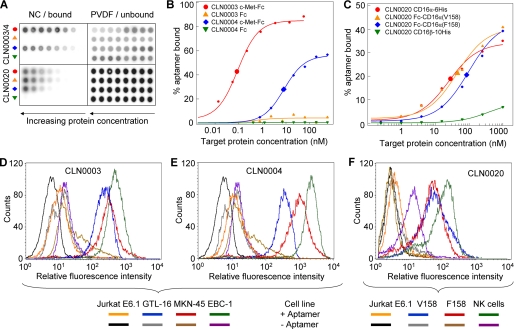

SELEX to select CD16 specific DNA aptamers using recombinant human CD16α-6His and CD16α Val-158 or Phe-158 alloforms expressed on recombinant Jurkat cells yielded enriched pools in all selections (supplemental Figs. S1–S5). Pool sequencing revealed 29 enriched aptamer families (of >90% sequence identity in the randomized region), in parts unique to one selection but also found throughout all pools of later SELEX rounds (supplemental Fig. S5 and supplemental Table S1). CD16α specific aptamers bound with 6–429 nm affinities to recombinant CD16α, but not to the highly related isoform CD16β (Fig. 2, A and C, supplemental Fig. S6). However, specific cellular binding to CD16α on recombinant Jurkat or NK cells was only observed for CLN0020 and CLN0123. CD16α specificity was confirmed by flow cytometry in which both NK cells and recombinant CD16α-positive cells were bound, and no unspecific binding to CD16-negative Jurkat E6.1 cells could be observed (Fig. 2). CLN0123 showed lower CD16α affinity (193 nm, supplemental Figs. S6 and S8) and, as expected, only weak cellular binding (supplemental Fig. S8). Competition dot blots revealed that CLN0020 and CLN0123 bound in or near the Fc binding domain of CD16α, but bound to different epitopes (supplemental Fig. S11).

FIGURE 2.

Biochemical and cellular binding characterization of CD16α and c-Met specific aptamers. A, representative dot blot raw data of three DNA aptamers CLN0003, CLN0004, and CLN0020. NC, nitrocellulose membrane readout; PVDF, polyvinylidene difluoride membrane readout. B, fitted binding curves for CLN0003 and CLN0004 to c-Met or Fc. C, fitted CLN0020 binding to both CD16α allotypes and minor binding to CD16β. Enlarged symbols represent calculated KD values. D, FACS analysis of CLN0003 binding to c-Met-positive GTL-16, MKN-45, and EBC-1 cells as compared with c-Met-negative control Jurkat E6.1 cells. E, CLN0004 binding to Met-positive GTL-16, MKN-45, and EBC-1 cells as compared with Jurkat E6.1. F, CLN0020 binding to NK cells and to both alloforms of CD16α presented on recombinant Jurkat cells, in comparison with the parental, CD16-negative Jurkat E6.1 cell line.

c-Met specific DNA aptamer sequences were isolated and characterized analogously to CD16α filter SELEX. CLN0003 and CLN0004 c-Met affinities (91 pm and 11 nm, respectively) were accompanied by specific cellular binding to c-Met-positive cell lines GTL-16, MKN-45, and EBC-1 (Fig. 2). Fc only as well as c-Met-negative Jurkat E6.1 cells were not bound (Fig. 2m B, D, and E). Biotinylated aptamers used for flow cytometry are shown in Fig. 3C, and selected aptamers are listed with sequence and affinities in Table 1.

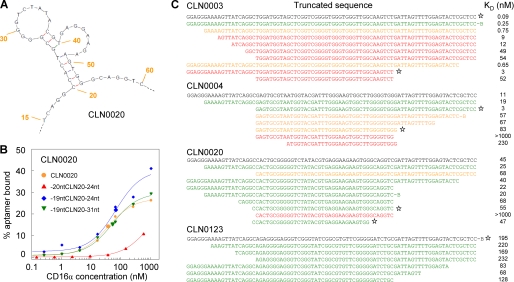

FIGURE 3.

Structure prediction and dot blot-based minimization. A, CLN0020 structure prediction indicating nucleotides 20–53 to be essential for structure formation. Numbering indicates base numbers of the full-length aptamer. B, affinity alteration upon removal of C20 in CLN0020 as determined in a dot blot. C, dot blot minimization studies of c-Met specific CLN0003 and CLN0004 as well as CD16α specific CLN0020 and CLN0123. Aptamers could be minimized individually up to a 34-mer CLN0020 core sequence. Asterisks mark the truncation variants used for the design of bi-specific aptamers.

TABLE 1.

Selected DNA aptamers binding c-Met or CD16α (a complete list can be found in supplemental Table S2)

| Aptamer | SELEX Target | Sequencea | KD | n | Frequency in SELEXb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | % | ||||

| CLN0003 | c-Met | TGGATGGTAGCTCGGTCGGGGTGGGTGGGTTGGCAAGTCT | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 3 | 3 |

| CLN0004 | c-Met | GAGTGCGTAATGGTACGATTTGGGAAGTGGCTTGGGGTGG | 11 ± 5 | 6 | 10 |

| CLN0015 | CD16 | GGCAGAAGAAATATCGAAACCCAGAATGGTCGGCCAGGCG | 24 ± 18 | 7 | 31 |

| CLN0020 | CD16 | CACTGCGGGGGTCTATACGTGAGGAAGAAGTGGGCAGGTC | 45 ± 28 | 10 | 4 |

| CLN0021 | CD16 | GCAAGTATGAGCGCAGGAGTTAGGTCCCGTGGCGATGGGT | 25 ± 19 | 5 | 40 |

| CLN0023 | CD16 | GACGTTAAGCTAGCAGGTGTTAGGTCCCGTGGTGATGAAT | 18 ± 14 | 5 | 2 |

| CLN0030 | CD16 | TAAACCCCAAAACAGTGCAACTAGGTGTAGGTCCCGTGGT | 6 ± 5 | 6 | 4 |

| CLN0118 | CD16 | ACGGACTCGCAAAAGGTGGAACAGGAGTGGGCCCCGCGGC | 31 ± 20 | 2 | 27 |

| CLN0123 | CD16 | AGAGGGGAGGGTCGGGTATCGGCGTGTTCGGGGGATCTGC | 193 ± 29 | 4 | 2 |

| CLN0126 | CD16 | GGCGTTGTCGGGCGCAGGTGTAGGCCTCGTGGTGGTGGGT | 46 ± 11 | 2 | 6 |

a Aptamer families are shown without the flanking constant regions used for selection.

b Frequencies of most sequence families varied in several analyzed selection rounds; the highest respective frequency is stated.

Structure Prediction and Minimization

Using the mfold tool yielded a reasonable structure prediction for CLN0020 only (Fig. 3A), and the predicted 34-mer core sequence could be confirmed in dot blots to be essential. Removal of only base C20 resulted in a distinct affinity loss (Fig. 3B), whereas adjacent sequences were redundant (Fig. 3C). Other aptamers could be minimized individually (Fig. 3C). With information about core and putative linker sequences given, these four partly minimized sequences were used for the construction of bi-specific aptamers.

Bi-specific Aptamers

24 different bi-specific aptamers (bsA1–bsA32) were designed (Table 2 and supplemental sequence data), and they were all synthesized as one individual oligonucleotide chain. Differently minimized aptamers were used to screen for a suitable linker length while retaining high affinities, and several kinds of linker were applied: a 15-deoxyadenosine linker (46), up to 44 nucleotides as “original” linker derived from full-length sequences known to be not essential for binding, as well as short polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains (supplemental Table S3). Assuming that an optimal bsA linker should bridge approximately the distance spanning from complementarity-determining regions to the Fc binding domain in the hinge region of an antibody, this distance was estimated from measurement of PDB entry 1T83 (47) to be ∼65 Å. Bi-specific aptamers were designed with putative linker lengths of ∼0–217 Å (Table 2 and supplemental Table S3).

TABLE 2.

Selected bi-specific aptamers (a complete list can be found in supplemental Table S3)

| Construct | 5′ aptamera | Linker sequence | 3′ aptamer | Putative linker lengthb | CD16α-6His KD | n | c-Met-Fc KD | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Å | nm | nm | ||||||

| bsA3 | -19CLN0020-24 | GCAGGTCAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA | -20CLN0004-23 | 154 | 39 ± 10 | 3 | 141 ± 16 | 6 |

| bsA31 | -19CLN0020-24 | GCAGGTCAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA | -20CLN0004 | 154 | 24 ± 4 | 4 | 92 ± 41 | 3 |

| bsA32 | -19CLN0020-31 | AAAAAAAAAAAAAAA | -20CLN0004 | 105 | 33 ± 1 | 2 | 119 ± 22 | 3 |

| bsA11 | -19CLN0020 | GCAGGTCGATTAGTTTTGGAGTACTCGCTCC | CLN0003 | 217 | 82 ± 9 | 2 | 0.16 | 1 |

| bsA15 | CLN0123 | GATTAGTTTTGGAGTACTC | CLN0003 | 140 | 174 | 1 | 0.22 | 1 |

| bsA17 | -19CLN0020-24 | GCAGGTC | CLN0003 | 49 | 19 ± 2 | 3 | 0.35 ± 0.09 | 6 |

| bsA21 | -19CLN0020-24 | GCAGGTCAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA | CLN0003 | 154 | 19 ± 2 | 2 | 0.28 ± 0.12 | 3 |

| bsA22 | -19CLN0020-31 | AAAAAAAAAAAAAAA | CLN0003 | 105 | 27 ± 5 | 2 | 0.24 ± 0.10 | 3 |

a 20CLN0020 denotes a 20-nucleotide truncation 5′ of CLN0020, CLN0020–24 designates a 24-nucleotide truncation 3′ of CLN0020, and so forth.

b Maximal distances bridged by nucleotide linkers were estimated from x-ray structures as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

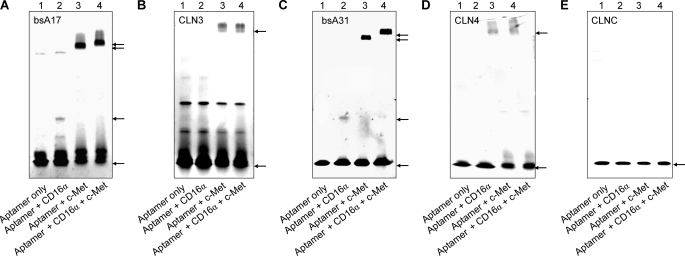

Most bi-specific aptamers retained high affinities in dot blots similar to the respective parental clones, such as picomolar c-Met affinities of CLN0003-derived bsA17 (Table 2 and supplemental Fig. S12). CD16α affinities of bi-specific aptamers based on CLN0020 were 19–82 nm, whereas bsA15 showed 174 nm CD16α affinity similar to the parental aptamer CLN0123 (Table 2). Simultaneous binding to both target proteins was confirmed for bsA17 and bsA31 by electrophoretic migration shift assays (EMSA; Fig. 4). All other bi-specific aptamers exhibited similar patterns (data not shown). Additional bio-layer interferometry confirmed simultaneous binding of bsA17 to c-Met-Fc and Fc-CD16α Val-158 (supplemental Fig. S13).

FIGURE 4.

Simultaneous binding of bi-specific aptamers bsA17 and bsA31 to CD16α and c-Met. A, CLN0003-derived bsA17 exhibited binding to CD16α-6His (additional band in lane 2) or c-Met-Fc fusion proteins (additional band in lane 3). This c-Met-Fc bound aptamer band shifted again upon the addition of CD16α-6His (lane 4). B, negative control parental single aptamer CLN0003 did not show a migration shift. Additional bands in all lanes could be due to unspecific aggregation. C and D, bsA31 and original single c-Met specific aptamer CLN0004 exhibited the same pattern as in A and B. E, negative control aptamer (CLNC) did not bind to any protein, as expected. Application of a gradient gel and size differences between CD16α-6His and c-Met-Fc fusion protein led to differently extended migration (lanes 2 and 3) and an expectedly minor but clearly present migration shift upon the addition of both target proteins (from lane 3 to 4). Arrows indicate the lowest migration frontier of specific aptamer bands.

Serum Stability

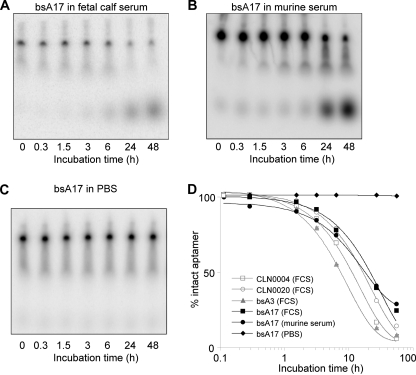

Because further functional assays demanded measurements in the presence of serum and stability was of interest for this therapeutic concept, the serum half-life of selected radiolabeled aptamers was determined to be 9.8 (CLN0004), 14.5 (CLN0020), 6.4 (bsA3), and 20.3 h (bsA17) in freshly thawed FCS. In addition, bsA17 remained stable in PBS for 48 h (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S14).

FIGURE 5.

Serum stability of major DNA aptamers. A and B, PAGE of bsA17 after incubation in FCS or murine serum, respectively. Bands at the migration level of the 0-h sample represent intact aptamer, whereas increasing signals at lower positions depict breakdown products. C, degradation of bsA17 in PBS was evaluated similarly but could not be observed within 48 h. D, intensity values were extracted from gels, the percentage of intact aptamer was calculated, and a curve was fitted to the resulting time course. Half-lives in FCS were determined as 9.8 (CLN0004), 14.5 (CLN0020), 6.4 (bsA3), and 20.3 h (bsA17), as well as 11 h for bsA17 in murine serum. Gel raw data of stability curves of additional aptamers are not shown.

ADCC Assays

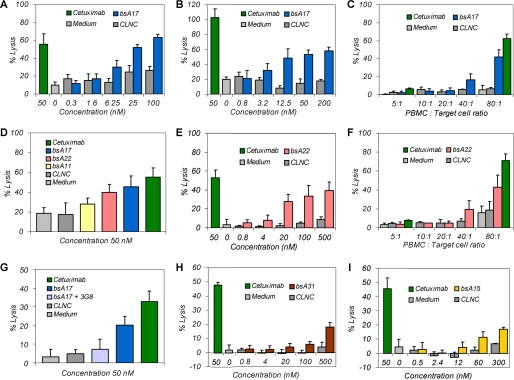

Bi-specific aptamers displaying high affinities and simultaneous binding to both target proteins as well as suitable serum stabilities were applied in functional ADCC assays. 16 suitable bi-specific aptamers were evaluated, including CLN0004-derived bsA31 (probably with suitable linker but with relatively low c-Met affinity) as well as CLN0003-based bsA11, -15, -17, and -22 (sharing high c-Met affinities combined with varying linkers; supplemental Tables S3 and S4). Bi-specific aptamer bsA17 mediated cellular cytotoxicity on GTL-16 and EBC-1 cells with a similar magnitude to antibody-positive control cetuximab (Fig. 6, A and B). This effect was reduced by either aptamer or effector cell dilution (Fig. 6, A–C). In addition, blocking of aptamer binding to CD16α by the addition of competing antibody 3G8 in 20-fold excess led to a significant decrease of specific cell lysis, further supporting the proposed mode of action (Fig. 6G). The bsA17-related bi-specific aptamer bsA22 similarly mediated specific GTL-16 cell lysis that could be diminished by reduction of aptamer concentration or effector cell amount (Fig. 6, E and F). CLN0004-derived bsA31, showing lower c-Met affinity (92 nm), induced weaker but distinct cytotoxicity at higher concentrations above 100 nm (Fig. 6H). Bi-specific aptamer bsA15 (with lower CD16α affinity) mediated specific GTL-16 cell lysis at comparable concentrations but with lower maximal cell lysis (Fig. 6I). When comparing bi-specific aptamers differing mostly in linker length, only linkers of ∼50–100 Å (of bsA17 and bsA22) were more suitable than longer linkers (217 Å of bsA11, Fig. 6D). It must be noted that putative linker lengths were calculated based on crystal structures of other DNA aptamers, so these linker lengths were estimations only. Although a precise EC50 determination was not feasible with mostly qualitative data obtained, the half-effective dose of bsA17 and bsA22 was in the low two-digit nanomolar range of 1–50 nm (Fig. 6, A, B, and E). Supplemental Table S4 gives a concluding overview of analyzed bi-specific aptamers and all properties that have been characterized.

FIGURE 6.

Functional ADCC assays of bi-specific aptamers. A, bi-specific aptamer bsA17-mediated specific GTL-16 cell lysis as compared with background levels of non-binding negative control aptamer (CLNC) and reference with medium only. B, similar bsA17-mediated concentration-dependent specific EBC-1 cell lysis. C, PBMC:target cell ratio reduction diminished cytotoxicity of both bsA17 and cetuximab at 50 nm. D, influence of linker lengths on bsA-mediated cell lysis. Estimated linker lengths were 49 Å for bsA17, 105 Å for bsA22 and 217 Å for bsA11. E and F, bsA22-induced specific cytotoxicity dependent on aptamer concentration and effector cell amount. G, the addition of 20-fold molar excess of antibody 3G8 resulted in a decrease of bsA17-mediated lysis due to inhibition of bsA17-binding to CD16α. H, bsA31 with lower c-Met affinity induced weaker but distinct lysis at higher concentrations. I, bsA15, composed of CLN0123 as a lower affinity CD16α binding entity, mediated weak but significant cytotoxicity as well. GTL-16 cells were applied in all measurements, except for B. Maximal lysis varied between individual experiments due to donor and CD16α allotype dependence. ADCC assays were performed 5 times with n = 4 (A), 4 times with n = 4 (B), 3 times with n = 3 (C), 3 times with n = 9 (D), 4 times with n = 4 (E), 1 time with n = 3 (F), 3 times with n = 9 (G), 2 times with n = 4 (H), and 1 time with n = 4 (I), and representative measurements are shown as mean ± S.D.

DISCUSSION

Aptamer Selection and Characterization

Both filter and cell SELEX approaches with CD16β counterselection led to the selection of CD16α specific DNA aptamers that did not bind CD16β. Although the specificity is surprising, it is in line with reported aptamers that can be highly specific (48, 49). In comparison with antibodies, CD16α specificity could prevent decoy of therapeutically applied bsA by soluble CD16β vastly present in the blood and ensure recruitment of CD16α-presenting effector cells. In addition, high affinity to both CD16α Val-158 and Phe-158 allotypes could enable a positive ADCC response in all patients, whereas in current antibody therapies, V/V allele carriers are associated with higher ADCC and improved clinical outcome than F/F patients (28, 31). Unexpectedly, aptamers that were enriched in cell SELEX and showed high CD16α affinity in dot blot assays mostly did not bind CD16α on the same cells as used for selection in flow cytometric measurements. Similarly, most filter SELEX-derived CD16α specific aptamers bound to recombinant CD16α-6His with high affinity, but not to cellular CD16α presented on recombinant Jurkat or NK cells. This could be due to disruption of their tertiary structure by binding of comparatively large streptavidin-phycoerythrin conjugates for staining purposes. Because such aptamers were probably not suitable to serve as one entity coupled to another aptamer in bi-specific constructs, optimization of the detection method (e.g. switching to direct dye labeling) was not performed.

Selected c-Met specific aptamers exhibited desirable properties such as high affinity and clear cellular binding (Fig. 2) but recognized the same epitope on c-Met (supplemental Fig. S11), impeding examination of epitope dependence for cytotoxic efficacy (cf. Ref. 50). This work represents the first description of DNA aptamers that show high specificity and affinity to c-Met or CD16α.

Design of Bi-specific Aptamers

The design of bi-specific aptamers included the development of linkers to approximately match the distance between complementarity-determining regions and the Fc binding domain in whole antibodies. The rationale was mimicking antibody architecture to improve the chance of enabling a similar cytotoxic effect. Mostly, linkers were designed based on the respective full-length sequences because minimization studies had shown that these sequences were not essential and did not interfere with high affinity binding. Additionally, 15-deoxyadenosine linkers were used as described by Müller et al. (46). Most linkers enabled both original affinity and simultaneous target protein binding (Table 2, Fig. 4, and supplemental Table S4). Calculated linker lengths were based on nucleotide distances in single-stranded portions of DNA aptamer crystal structures and consequently represented an estimate only. Coupling of bi-specific aptamers was achieved by complete synthesis rather than hybridization to obtain more uniform bi-specific aptamers.

Serum half-lives were determined in murine and fetal calf serum to be 6.4–20.3 h (Fig. 5). Stabilities were in accordance with comparable studies of DNA aptamer degradation in human serum and plasma, reporting strongly varying half-lives from several minutes to 42 h (51–53). Differences may reflect diverse applied methods (51, 54) or a strong sequence dependence of nuclease degradation (55) including a rigid structure versus exposed termini (5). In addition to high affinity simultaneous binding, bsA serum stabilities provided clear evidence of the suitability for functional evaluation.

Functional Analyses

Aptamer-mediated cellular cytotoxicity was dependent on the concentration of bi-specific aptamers and the amount of applied effector cells. Reduced lysis upon CD16 binding blocking by 3G8 provided proof for the suggested mode of action. Specific cytotoxicity was demonstrated for independent human gastric and lung cancer cell lines and determined 3–6 times in independent experiments applying effector cells of different blood donors. Taken together, these results validate that bi-specific aptamers can mediate specific cellular cytotoxicity. Maximal specific cell lysis (Fig. 6) was similar to comparable bi-specific scFv formats (35, 56, 57) and therapeutical antibodies (58). Activation with IL-2 or longer incubation could have further increased maximal lysis (59, 60). Note that the actual effector:target cell (E:T) ratio was ∼8:1 when applying 80:1 PBMC:target cells (32). Because ADCC-mediating c-Met specific antibodies R13 and R28 (61) were not available for comparative studies, EGF receptor-specific cetuximab was used as a qualitative antibody-positive control and as an indicator for a valid experimental setup including e.g. suitable NK cell reactivity.

In quantitative comparison with the potency reported for the two c-Met specific antibodies R13 and R28 of 60 nm EC50 (when synergistically applied (61)), half-effective concentrations were lower for individually applied bsA17 or bsA22 (10–50 nm; Fig. 6). Other published c-Met antibody therapeutics comprise only Fab fragments (11) or Escherichia coli-produced monovalent antibodies (MetMAb (12)) that do not induce cellular cytotoxicity. Therapeutic “enhanced ADCC” antibodies target other surface proteins and exhibit EC50 values in a low ng/ml range translating to low picomolar concentrations (58). CD16α-targeting bi-specific scFv formats that are comparable with bsAs described herein show half-maximum effective doses at low nanomolar (62) to three-digit picomolar concentrations (45, 57), whereas similar constructs as trivalent bi-specific triple bodies mediate ADCC with low picomolar EC50 values (35, 56). Finally, CD3 specific T cell recruiting BiTEs exhibit half-maximum effective doses partly below 1 ng/ml, which equals low picomolar to femtomolar concentrations (59, 60). Due to target protein dependence of ADCC, direct comparison of bi-specific aptamers is only feasible to c-Met antibodies applied to GTL-16 cells, and single bi-specific aptamers bsA17 or bsA22 alone exhibit a higher potency than synergistically applied c-Met antibodies R13 and R28 (61).

Cytotoxicity was mediated by high affinity bsAs containing linkers that maximally bridge ∼49–154 Å, a distance similar to ∼65 Å in antibodies. In accordance to these findings, effective bi-specific scFv molecules contain Gly-Ser linkers bridging similar distances (e.g. 110 Å in Ref. 35). Decreased cytolytic efficacies were observed with increasing linker lengths, and linkers with putative separation distances over ∼200 Å did not elicit significant cytotoxicity, regardless of high affinities to both target proteins (e.g. bsA11 in Fig. 6D). This indicates the importance of the spatial distance for enabling cellular cytotoxicity (as evaluated in another way by Bluemel et al. in Ref. 50).

Perspective

The bi-specific aptamers described herein exhibit affinities similar to certain BiTEs with three-digit picomolar to low nanomolar tumor antigen binding and medium affinity effector specific antigen binding (63). These similar characteristics point out that bi-specific aptamers could induce serial killing of NK cells (cf. 64). However, the efficacy of BiTEs clearly supersedes that of the first generation bi-specific aptamers reported herein. Relocalization of cytotoxic T cells instead of NK cells by targeting CD3 instead of CD16 could potentially increase the efficacy of bi-specific aptamers. In this study, c-Met was used to bring NK cells into close proximity of tumor cells to trigger ADCC, but the application range of bi-specific aptamers could be broadened by facile exchange of the tumor-specific portion targeting further tumor markers such as the validated targets EpCAM or EGF receptor.

Future work could focus on in vivo evaluations using xenograft mouse models expressing human CD16 receptors (65, 66). Despite positive results in functional cellular assays, issues of serum stability and poor pharmacokinetics remain to be solved. Stability can be further improved, e.g. by usage of modified nucleotides with substituted 2′ residues. Suitable 2′-hydroxy-purine 2′-fluoro-pyrimidine oligonucleotide and 2′-methoxy-purine 2′-fluoro-pyrimidine oligonucleotide aptamers (67), sharing all essential characteristics with the successfully employed DNA aptamer CLN0020, are already available (supplemental Figs. S15–S17). Renal clearance could be reduced by aptamer coupling to PEG (68), hydroxyethyl starch, or other glycosylation (69, 70). In a more elegant approach, neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn)-mediated recycling of antibodies (71) could be mimicked by additional coupling of aptamers binding to the neonatal Fc receptor FcRn at pH 6 but not at pH 7.4.3 In contrast to antibodies, aptamers as single binding entities possess the property of binding tumor-specific surface receptors without the risk of activation (11). Bi-specific aptamers optimized in such ways could mimic most eligible features of comparable therapeutic antibody approaches but exceed them, for example, with uniform and cost-effective synthesis as well as a proposed absence of immunogenicity (13, 73).

So far, work was published on linkage of aptamers that aimed at delivery of payloads (8, 74), an affinity increase by avidity, and a stronger receptor (75) or enzyme inhibition (76–78). Furthermore, two copies of RNA aptamers were assembled on an oligonucleotide-based scaffold to induce receptor activation (79), and with it, T cell co-stimulation that led to tumor growth inhibition in mice (6). Bi-specific aptamers have also been developed to capture different ligands in diagnostic applications (80). To our knowledge, the work presented herein describes for the first time the gain of a tumor-effective function of two distinct binding entities by linkage into a bi-specific aptamer mediating tumor cell lysis. Bi-specific aptamers represent a suitable starting concept for the development of stable, nucleotide-based therapeutics to mediate lysis of c-Met-positive tumors. A facile exchange of the tumor-specific entity could broaden the approach to treatment of further cancer types, thereby opening new avenues for tumor therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Angelika-Nicole Helfrich (Merck Serono) for providing c-Met specific DNA aptamers and Nils Bahl (Merck Serono) for selection of CD16α specific 2′-methoxy-purine 2′-fluoro-pyrimidine oligonucleotide aptamers.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S17 and Tables S1–S4.

R. Günther, unpublished results.

- SELEX

- systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment

- ADCC

- antibody- or aptamer-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

- bsA

- bi-specific aptamer

- FcγR

- Fcγ receptor

- CD16

- FcγRIII

- NK cells

- natural killer cells

- scFv

- single-chain Fv fragment

- PBMC

- peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ruckman J., Green L. S., Beeson J., Waugh S., Gillette W. L., Henninger D. D., Claesson-Welsh L., Janjić N. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 20556–20567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sazani P. L., Larralde R., Szostak J. W. (2004) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 8370–8371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ellington A. D., Szostak J. W. (1990) Nature 346, 818–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tuerk C., Gold L. (1990) Science 249, 505–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Di Giusto D. A., Knox S. M., Lai Y., Tyrelle G. D., Aung M. T., King G. C. (2006) Chembiochem 7, 535–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McNamara J. O., Kolonias D., Pastor F., Mittler R. S., Chen L., Giangrande P. H., Sullenger B., Gilboa E. (2008) J. Clin. Invest. 118, 376–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dassie J. P., Liu X. Y., Thomas G. S., Whitaker R. M., Thiel K. W., Stockdale K. R., Meyerholz D. K., McCaffrey A. P., McNamara J. O., 2nd, Giangrande P. H. (2009) Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 839–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhou J., Swiderski P., Li H., Zhang J., Neff C. P., Akkina R., Rossi J. J. (2009) Nucleic. Acids Res. 37, 3094–3109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Orava E. W., Cicmil N., Gariépy J. (2010) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1798, 2190–2200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aarden L., Ruuls S. R., Wolbink G. (2008) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 20, 431–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pacchiana G., Chiriaco C., Stella M. C., Petronzelli F., De Santis R., Galluzzo M., Carminati P., Comoglio P. M., Michieli P., Vigna E. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 36149–36157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jin H., Yang R., Zheng Z., Romero M., Ross J., Bou-Reslan H., Carano R. A., Kasman I., Mai E., Young J., Zha J., Zhang Z., Ross S., Schwall R., Colbern G., Merchant M. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 4360–4368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. White R. R., Sullenger B. A., Rusconi C. P. (2000) J. Clin. Invest. 106, 929–934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Que-Gewirth N. S., Sullenger B. A. (2007) Gene Ther. 14, 283–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bates P. J., Choi E. W., Nayak L. V. (2009) Methods Mol. Biol. 542, 379–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Keefe A. D., Pai S., Ellington A. (2010) Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 9, 537–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zompi S., Colucci F. (2005) Immunol. Lett 97, 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sliwkowski M. X., Lofgren J. A., Lewis G. D., Hotaling T. E., Fendly B. M., Fox J. A. (1999) Semin. Oncol. 26, 60–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Desjarlais J. R., Lazar G. A., Zhukovsky E. A., Chu S. Y. (2007) Drug Discov. Today 12, 898–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Farag S. S., VanDeusen J. B., Fehniger T. A., Caligiuri M. A. (2003) Int. J. Hematol. 78, 7–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim S., Iizuka K., Aguila H. L., Weissman I. L., Yokoyama W. M. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 2731–2736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Roda J. M., Parihar R., Magro C., Nuovo G. J., Tridandapani S., Carson W. E., 3rd (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nimmerjahn F., Ravetch J. V. (2006) Immunity 24, 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bruhns P., Iannascoli B., England P., Mancardi D. A., Fernandez N., Jorieux S., Daëron M. (2009) Blood 113, 3716–3725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harrison D., Phillips J. H., Lanier L. L. (1991) J. Immunol. 147, 3459–3465 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li P., Jiang N., Nagarajan S., Wohlhueter R., Selvaraj P., Zhu C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6210–6221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huizinga T. W., de Haas M., van Oers M. H., Kleijer M., Vilé H., van der Wouw P. A., Moulijn A., van Weezel H., Roos D., von dem Borne A. E. (1994) Br. J. Haematol. 87, 459–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cartron G., Dacheux L., Salles G., Solal-Celigny P., Bardos P., Colombat P., Watier H. (2002) Blood 99, 754–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. López-Albaitero A., Lee S. C., Morgan S., Grandis J. R., Gooding W. E., Ferrone S., Ferris R. L. (2009) Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 58, 1853–1864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cui Z., Willingham M. C., Hicks A. M., Alexander-Miller M. A., Howard T. D., Hawkins G. A., Miller M. S., Weir H. M., Du W., DeLong C. J. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 6682–6687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Taylor R. J., Chan S. L., Wood A., Voskens C. J., Wolf J. S., Lin W., Chapoval A., Schulze D. H., Tian G., Strome S. E. (2009) Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 58, 997–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wallace M. E., Smyth M. J. (2005) Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 27, 49–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arndt M. A., Krauss J., Kipriyanov S. M., Pfreundschuh M., Little M. (1999) Blood 94, 2562–2568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McCall A. M., Adams G. P., Amoroso A. R., Nielsen U. B., Zhang L., Horak E., Simmons H., Schier R., Marks J. D., Weiner L. M. (1999) Mol. Immunol. 36, 433–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Singer H., Kellner C., Lanig H., Aigner M., Stockmeyer B., Oduncu F., Schwemmlein M., Stein C., Mentz K., Mackensen A., Fey G. H. (2010) J. Immunother. 33, 599–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Baeuerle P. A., Reinhardt C. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 4941–4944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eder J. P., Vande Woude G. F., Boerner S. A., LoRusso P. M. (2009) Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 2207–2214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tsarfaty I., Rong S., Resau J. H., Rulong S., da Silva P. P., Vande Woude G. F. (1994) Science 263, 98–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gentile A., Trusolino L., Comoglio P. M. (2008) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 27, 85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bladt F., Riethmacher D., Isenmann S., Aguzzi A., Birchmeier C. (1995) Nature 376, 768–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stellrecht C. M., Gandhi V. (2009) Cancer Lett 280, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Takayama H., LaRochelle W. J., Sharp R., Otsuka T., Kriebel P., Anver M., Aaronson S. A., Merlino G. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 701–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tsang J., Joyce G. F. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 262, 31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zuker M. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3406–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bruenke J., Fischer B., Barbin K., Schreiter K., Wachter Y., Mahr K., Titgemeyer F., Niederweis M., Peipp M., Zunino S. J., Repp R., Valerius T., Fey G. H. (2004) Br. J. Haematol. 125, 167–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Müller J., Wulffen B., Pötzsch B., Mayer G. (2007) Chembiochem 8, 2223–2226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Radaev S., Motyka S., Fridman W. H., Sautes-Fridman C., Sun P. D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem., 276, 16469–16477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jenison R. D., Gill S. C., Pardi A., Polisky B. (1994) Science 263, 1425–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shangguan D., Li Y., Tang Z., Cao Z. C., Chen H. W., Mallikaratchy P., Sefah K., Yang C. J., Tan W. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11838–11843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bluemel C., Hausmann S., Fluhr P., Sriskandarajah M., Stallcup W. B., Baeuerle P. A., Kufer P. (2010) Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 59, 1197–1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Di Giusto D. A., King G. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46483–46489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schmidt K. S., Borkowski S., Kurreck J., Stephens A. W., Bald R., Hecht M., Friebe M., Dinkelborg L., Erdmann V. A. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 5757–5765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Peng C. G., Damha M. J. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 4977–4988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shaw J. P., Fishback J. A., Cundy K. C., Lee W. A. (1995) Pharm. Res. 12, 1937–1942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Choi E. W., Nayak L. V., Bates P. J. (2010) Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 1623–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kellner C., Bruenke J., Stieglmaier J., Schwemmlein M., Schwenkert M., Singer H., Mentz K., Peipp M., Lang P., Oduncu F., Stockmeyer B., Fey G. H. (2008) J. Immunother. 31, 871–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kügler M., Stein C., Kellner C., Mentz K., Saul D., Schwenkert M., Schubert I., Singer H., Oduncu F., Stockmeyer B., Mackensen A., Fey G. H. (2010) Br. J. Haematol. 150, 574–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lazar G. A., Dang W., Karki S., Vafa O., Peng J. S., Hyun L., Chan C., Chung H. S., Eivazi A., Yoder S. C., Vielmetter J., Carmichael D. F., Hayes R. J., Dahiyat B. I. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4005–4010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mack M., Riethmüller G., Kufer P. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 7021–7025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brischwein K., Schlereth B., Guller B., Steiger C., Wolf A., Lutterbuese R., Offner S., Locher M., Urbig T., Raum T., Kleindienst P., Wimberger P., Kimmig R., Fichtner I., Kufer P., Hofmeister R., da Silva A. J., Baeuerle P. A. (2006) Mol. Immunol. 43, 1129–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. van der Horst E. H., Chinn L., Wang M., Velilla T., Tran H., Madrona Y., Lam A., Ji M., Hoey T. C., Sato A. K. (2009) Neoplasia 11, 355–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kipriyanov S. M., Cochlovius B., Schäfer H. J., Moldenhauer G., Bähre A., Le Gall F., Knackmuss S., Little M. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Baeuerle P. A., Kufer P., Lutterbüse R. (2003) Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 5, 413–419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hoffmann P., Hofmeister R., Brischwein K., Brandl C., Crommer S., Bargou R., Itin C., Prang N., Baeuerle P. A. (2005) Int. J. Cancer 115, 98–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Li M., Wirthmueller U., Ravetch J. V. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 183, 1259–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nimmerjahn F., Ravetch J. V. (2008) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 34–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Keefe A. D., Cload S. T. (2008) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 12, 448–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pendergrast P. S., Marsh H. N., Grate D., Healy J. M., Stanton M. (2005) J. Biomol. Tech. 16, 224–234 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kontermann R. E. (2009) BioDrugs 23, 93–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Constantinou A., Chen C., Deonarain M. P. (2010) Biotechnol. Lett 32, 609–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Roopenian D. C., Akilesh S. (2007) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 715–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Deleted in proof.

- 73. Kaur G., Roy I. (2008) Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 17, 43–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chu T. C., Twu K. Y., Ellington A. D., Levy M. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, e73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Santulli-Marotto S., Nair S. K., Rusconi C., Sullenger B., Gilboa E. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 7483–7489 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kim Y., Cao Z., Tan W. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 5664–5669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Michalowski D., Chitima-Matsiga R., Held D. M., Burke D. H. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 7124–7135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Müller J., Freitag D., Mayer G., Pötzsch B. (2008) J. Thromb. Haemost. 6, 2105–2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Dollins C. M., Nair S., Boczkowski D., Lee J., Layzer J. M., Gilboa E., Sullenger B. A. (2008) Chem. Biol. 15, 675–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tahiri-Alaoui A., Frigotto L., Manville N., Ibrahim J., Romby P., James W. (2002) Nucleic. Acids Res. 30, e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Dang C., Jayasena S. D. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 264, 268–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.