Abstract

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are chronic inflammatory bowel diseases that often involve organs other than those of the gastrointestinal tract. Immune-related extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) are usually related to disease activity, but sometimes may take an independent course. Globally, about one third of patients develop these systemic manifestations. Phenotypic classification shows that certain subsets of patients are more susceptible to developing EIMs, which frequently occur simultaneously in the same patient overlapping joints, skin, mouth, and eyes. The clinical spectrum of these manifestations varies from mild transitory to very severe lesions, sometimes more incapacitating than the intestinal disease itself. The great majority of these EIMs accompany the activity of intestinal disease and patients run a higher risk of a severe clinical course. For most of the inflammatory EIMs, the primary therapeutic target remains the bowel. Early aggressive therapy can minimize severe complications and maintenance treatment has the potential to prevent some devastating consequences.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Immune-related extraintestinal manifestations, Treatment

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are clinically heterogeneous disorders with the potential for systemic involvement. The clinical spectrum of these extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) varies from mild transitory to very severe lesions, sometimes more incapacitating than the intestinal disease itself.

Most of the EIMs, such as those that occur in the joints, skin, mouth and eyes, are related to the activity of the bowel disease and, consequently, have been referred to as “inflammatory”. Others are associated with autoimmunity, while further manifestations result from nutritional or metabolic dysfunction.

Patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) are considered a more homogeneous group than patients with Crohn’s disease (CD). The most important significant variables in UC are the extent of colonic involvement and the activity of disease.

The current clinical practice for management of CD patients should take into account a major number of events, such as age at diagnosis, location, behavior, intestinal complications, EIM symptoms and previous medical or surgical treatment.

The aim of the present manuscript is to review the common immune-related EIMs and to evaluate whether they are important targets of treatment or just an expression of disease activity.

PREVALENCE OF EIMS IN IBD

Globally, about one third of patients with IBD develop inflammatory systemic manifestations. The frequency of these manifestations in previous major studies ranged from 21% to 41%, depending on the patient population and criteria used[1-5]. In our series they were observed in 26% of the patients and were more common in CD than in UC patients. However, during the follow-up period the cumulative probability of developing EIMs increased from 12% at diagnosis up to 30%[2].

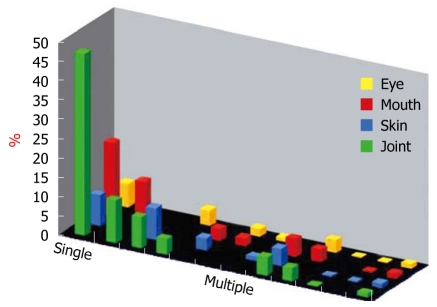

We have studied the course of CD according to the Vienna classification and clinical activity[6]. More recently, in this cohort of 480 patients followed from diagnosis, we investigated the cumulative probability of inflammatory EIMs, which varied from 22% at diagnosis to 40% 10 years after diagnosis. Here we showed that a single manifestation occurred in 80 patients, whereas multiple manifestations overlapping joints, skin, mouth, and eyes occurred in 89 patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Associations of the four major inflammatory extraintestinal manifestations in 169 of 480 Crohn’s disease patients.

The specific disease entities considered were peripheral and axial arthritis (joints), erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum (skin), aphthous stomatitis (mouth), and episcleritis and uveitis (eye). Thus, it was confirmed that two or more manifestations in the same patient occurred more frequently than would be expected by chance alone (P < 0.001)[2,4].

Patients with one of these EIMs not only run a high risk of a repetition of the same manifestation, but also of having any of the other associated manifestations. In our patients the cumulative probability of a second manifestation was about 70% at 10 years of follow-up.

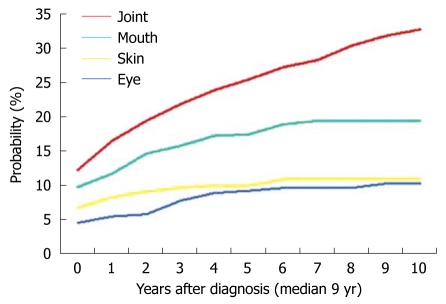

Moreover, we have also studied the appearance of various EIMs throughout the clinical course and it was observed that some types of manifestations are more likely to appear during the early stages. This was particularly evident for skin manifestations, which tend to occur in most of the patients for the first time during the first 2 years of follow-up (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative probability of having a repetition of the same inflammatory extraintestinal manifestations.

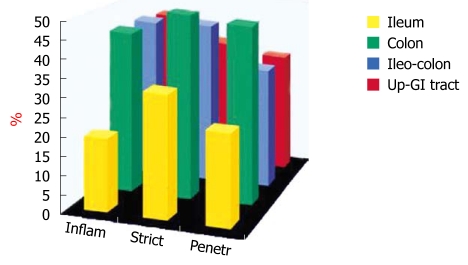

We have also studied the probability of EIMs in different subsets of CD patients[7]. The location of disease was significantly different between patients who had and who did not have EIMs and was higher in those with colonic involvement (P < 0.005) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of inflammatory extraintestinal manifestations according to the Vienna classification in 169 Crohn’s disease patients.

To calculate the clinical course, we constructed a Markov model to study the probability of maintaining a similar state during the following year. Patients were divided into two exclusive groups, those who had and those who did not have manifestations. Patients with EIMs ran a higher risk of a severe clinical course (P < 0.005)[7].

In UC it is still controversial whether EIMs are correlated with the extent of colonic involvement, although they are usually related to the activity of the disease.

DESCRIPTION OF EIMS

Joint manifestations

Peripheral involvement of the joints is the most common of the EIMs and it affects between 5% and 20% of IBD patients[8-11]. In our series, arthritis occurred frequently, twice as often in CD as in UC (20% vs 11%)[2]. The joint involvement is mostly monoarticular, asymmetrical, transitory and migrating. Generally, it is of short duration and is unaccompanied by residual deformity or radiological change.

The diagnosis is based on clinical signs of synovitis, eventually associated with enthesitis. However, using articular scintigraphy, a sensitive indicator of active joint disease, asymptomatic and mild forms of synovitis could be detectable. We have evaluated articular involvement, clinically and by scintigraphy, in forty-two IBD patients. More affected joints have been diagnosed scintigraphically than clinically, indicating that the prevalence of this complication could be much higher than generally believed[11].

The clinical activity of synovitis tends to parallel that of the intestinal disease. In most instances, the synovitis symptoms follow rather than precede IBD and recurrence is common, frequently coinciding with a flare-up of intestinal disease. Also, they are more common in patients with extensive colitis.

Regarding treatment, the main issue should be to control the clinical activity of the underlying bowel disease. Thereafter, there is agreement that this manifestation generally responds well to medical or surgical treatment targeted to the bowel disease. Conventional treatments for mild to moderate inflamed joints consist of acetaminophen, sulfasalazine, corticosteroids, and if necessary nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Furthermore, the majority of IBD patients with active intestinal disease and peripheral arthritis will notice an improvement of joint symptoms after receiving infliximab[12].

Ankylosing spondylitis, as defined by the Rome criteria, is associated with IBD in 5% of cases and it runs an independent course to the IBD[8-10]. In fact, the onset of ankylosing spondylitis is not related to the onset of IBD and usually precedes it. Also, there is no association between the severity of IBD and axial arthritis.

The proven efficacy of infliximab therapy in CD and rheumatoid arthritis has led to the suggestion that anti-tumor necrosis factor-α treatment might also be a useful agent in the management of spondyloarthropathies associated with CD.

In several open studies, infliximab has been used in patients with ankylosing spondylitis, leading to clinical, biologic and imaging improvement[12-15].

In our clinical practice the use of infliximab in patients with spondyloarthropaties associated with CD has resulted in an impressive improvement in clinical and laboratory abnormalities. The same has been reported in other uncontrolled studies[12,16]. In a multicentric, randomized, double-blind international trial to evaluate the efficacy of infliximab maintenance therapy in patients with moderate to severe active CD (ACCENT I), it has been reported that maintenance therapy with infliximab is superior to a single dose in resolving arthritis/arthralgia[17].

Clinical data suggest that intensive therapeutic strategies using biologic drugs should be tailored to the individual with severe or refractory articular disease. However, long-term studies with larger numbers of patients will be necessary to determine the patients who are most likely to benefit from these specific treatments. Furthermore, careful attention should be paid to the potential adverse events; mainly infections and malignancy.

Skin manifestations

There is a wide range of dermatological manifestations reported in patients with IBD, of which erythema nodosum is the most common form of reactive eruption. The prevalence of erythema nodosum has been reported to occur in up to 15% of patients[1], although other, more recent studies have reported that the prevalence may be considerably lower[10,18]. In fact, in a previous report from our group it was seen in 8% and 3% of CD and UC patients, respectively[2]. Clinically, erythema nodosum appears in conjunction with symptoms of active bowel disease and is most common in females, patients with large intestine involvement and peripheral arthritis[2].

Erythema nodosum lesions usually respond to treatment with corticosteroids used to control the bowel flare-up. In refractory cases, potassium iodide, colchicine, hydroxychloroquine, and thalidomide have been used[19]. More recently a successful response to infliximab in severe erythema nodosum has also been reported[20]. We have used this treatment in a patient with colonic CD complicated with severe lesions of erythema nodosum and arthritis, refractory to high doses of steroids, which resulted in a rapid and complete resolution of skin and articular manifestations (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Severe lesions of erythema nodosum treated with infliximab.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a severe and debilitating skin disorder, characterized by the occurrence of nodules and pustules that rapidly enlarge and ulcerate. Lesions typically occur on the extensor surfaces of the lower extremities, but may also be found elsewhere. Since there is no specific test, the diagnosis can be difficult, only being established when the clinical and histopathological pictures are consistent with pyoderma gangrenosum, and other pustular or ulcerative dermatoses have been excluded.

This chronic ulcerating skin disorder can be found in 0.4%-2% of patients with IBD[10,19]. Patients with severe disease and colonic involvement are most likely to develop this complication. Pyoderma gangrenosum may run a course independent of the IBD, but sometimes coincides with an exacerbation of the underlying intestinal disease.

Management of pyoderma gangrenosum continues to be a therapeutic challenge and usually requires aggressive local and systemic therapy. High doses of oral prednisone and/or intralesional injections of corticosteroids are generally effective in the management[21]. However, the best form of treatment, particularly in patients with inactive intestinal disease, has not been established yet. Several clinical cases have been successfully treated with intravenous cyclosporine, oral and topical tacrolimus, or mycophenolate mofetil and granulocytapheresis[22-27].

In several reports patients treated with infliximab have shown rapid healing of their lesions[28]. We have successfully treated one patient in this way (Figure 5). In a recent controlled study, 6 of 13 patients with pyoderma gangrenosum were successfully treated with infliximab[29]. Thus, infliximab treatment is highly effective in healing refractory lesions and has become the first choice for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum.

Figure 5.

Pyoderma gangrenosum before, during and after treatment with infliximab.

Oral ulceration

Aphthous ulcers are the most common oral lesions in IBD; they occur in about 10% of patients. Aphthae are shallow, round ulcers with a central fibrinous membrane and erythematous halo (Figure 6). Their onset is usually sudden, coinciding with the flare-up of intestinal disease and occurring simultaneously with other EIMs[2,30].

Figure 6.

Aphthous ulcers in the buccal mucosa and on the tongue.

Many similarities exist between CD and intestinal Behçet’s disease. Both diseases have similar EIMs, particularly aphthous ulcers, which are an initial symptom in the majority of patients with Behçet’ disease[31].

Oral ulcers usually respond to the treatment of the underlying bowel disease, but sometimes they may be resistant to conventional therapy. In these situations topical applications of steroids or tacrolimus may be of use[32]. Oral thalidomide has been reported to be beneficial in the treatment of aphthous stomatitis related to HIV infection and could be tried for lesions in patients with IBD. Infiximab has also been used in the treatment of patients with CD complicated with gigantic oral ulcers[7].

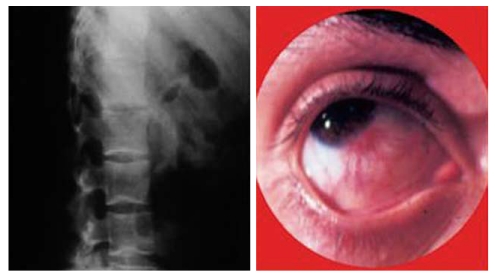

Eye manifestations

Ophthalmologic complications have been reported to occur in up to 12% of patients according to the published literature and these complications seem to occur more frequently in CD patients[33]. The most common complications are episcleritis, scleritis, and uveitis. Uveitis is the most serious complication and may be the cause of significant morbidity. Often it occurs independently of the bowel disease and is particularly associated with the musculoskeletal EIMs[34] (Figure 7). Specific treatment may include topical and systemic steroids. In the management of ophthalmologic manifestations, immunosuppression is often required. Infliximab has been reported to have a beneficial effect in a few patients suffering from CD with uveitis and spondyloarthropathy, and is increasingly being used in both acute and chronic ocular inflammatory manifestations of IBD[12,35-37].

Figure 7.

Ankylosing spondylitis and uveitis in the same patient.

Hepatobiliary manifestations

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is the most common immune-mediated hepatobiliary disease. It is a chronic, progressive, cholestatic disorder characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. The prevalence of IBD (mostly UC) is about 75% and PSC complicates approximately 2%-5% of cases of UC and 0.7%-3.4% of cases of CD[10,38].

Most patients with PSC are diagnosed when asymptomatic with abnormal liver function tests performed in routine follow-up. Symptoms of PSC usually consist of fatigue, pruritus, right upper quadrant pain, fever, jaundice, and weight loss. Magnetic resonance (MR) cholangiography is often used for diagnosis of PSC and avoids the complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Liver biopsy is not always necessary where typical features are present on MR cholangiography[39].

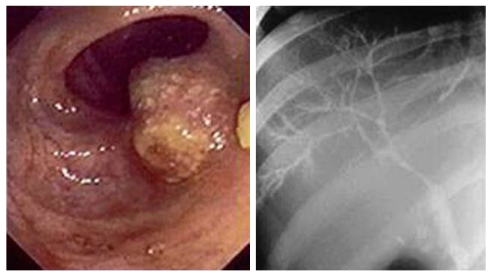

IBD-PSC patients have a specific phenotype, characterized by extensive, mild disease with a particularly high risk of colonic dysplasia and carcinoma (Figure 8), as well as an increased risk of bile duct cancer. Yearly surveillance colonoscopy is recommended for those patients with colonic involvement[40,41].

Figure 8.

ERCP showing sclerosing cholangitis and endoscopic view of carcinoma of the colon observed in the same patient.

The medical management of PSC remains controversial. Ursodeoxycholic acid is widely used for this indication, and the best results have been obtained with high dose (up to 22-25 mg/kg). Moreover, the evidence that this medication prevents progression of PSC and that it may reduce the high risk of colonic cancer in these patients may become an indication for its use[38]. Liver transplant is the only treatment for patients with advanced PSC, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 80%. However, the optimum timing for transplantation remains a difficult decision.

CONCLUSION

During the course of IBD, EIMs related to the activity of intestinal inflammation are quite common. Phenotypic classification shows that certain subsets of patients are more susceptible to developing EIMs. They also have a higher probability of maintaining active disease during the clinical course. For most of the inflammatory EIMs, the primary therapeutic target remains the bowel. Early aggressive therapy with biologic drugs may be required for several EIMs and maintenance treatment has the potential to prevent some devastating consequences. Long-term studies with larger numbers of patients will be necessary to determine the patients who are most likely to benefit from specific treatments.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Dr. Stephan Johannes Ott, PhD, MD, Clinic for Internal Medicine I, University-Hospital Schleswig-Holstein (UK S-H), Campus Kiel, Arnold-Heller-Str. 3, Hs. 6, 24105 Kiel, Germany

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Greenstein AJ, Janowitz HD, Sachar DB. The extra-intestinal complications of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: a study of 700 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976;55:401–412. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veloso FT, Carvalho J, Magro F. Immune-related systemic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. A prospective study of 792 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;23:29–34. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199607000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snook JA, de Silva HJ, Jewell DP. The association of autoimmune disorders with inflammatory bowel disease. Q J Med. 1989;72:835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rankin GB, Watts HD, Melnyk CS, Kelley ML Jr. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study: extraintestinal manifestations and perianal complications. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:914–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N. The prevalence of extraintestinal diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1116–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veloso FT, Ferreira JT, Barros L, Almeida S. Clinical outcome of Crohn's disease: analysis according to the vienna classification and clinical activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:306–313. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veloso FT. Extraintestinal manifestations - important target of treatment or just an expression of disease activity? In: Herfarth H, Feagan BG, Fölsch UR, Schölmerich J, Vatn MH, et al., editors. Targets of treatment in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003. pp. 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meuwissen SGM, Crusius JBA, Peña AS, Dekker-Saeys AJ, Dijkmans BAC. Spondyloarthropathy and idiopathic inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1997;3:25–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Vos M. Review article: joint involvement in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 4:36–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams H, Orchard T. Management of the extraintestinal manifestations of IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis Monit. 2009;10:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veloso FT. Inflammatory extraintestinal manifestations associated with IBD. In: Monteiro E, Tavarela Veloso F, et al., editors. Inflammatory bowel diseases: new insight into mechanisms of inflammation and challenges in diagnosis and treatment. Lancaster: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 232–236. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrie A, Regueiro M. Biologic therapy in the management of extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1424–1429. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone M, Salonen D, Lax M, Payne U, Lapp V, Inman R. Clinical and imaging correlates of response to treatment with infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1605–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun J, Baraliakos X, Listing J, Fritz C, Alten R, Burmester G, Krause A, Schewe S, Schneider M, Sörensen H, et al. Persistent clinical efficacy and safety of anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy with infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis over 5 years: evidence for different types of response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:340–345. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.075879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van den Bosch F, Kruithof E, De Vos M, De Keyser F, Mielants H. Crohn's disease associated with spondyloarthropathy: effect of TNF-alpha blockade with infliximab on articular symptoms. Lancet. 2000;356:1821–1822. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Generini S, Giacomelli R, Fedi R, Fulminis A, Pignone A, Frieri G, Del Rosso A, Viscido A, Galletti B, Fazzi M, et al. Infliximab in spondyloarthropathy associated with Crohn's disease: an open study on the efficacy of inducing and maintaining remission of musculoskeletal and gut manifestations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1664–1669. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.012450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer L, Keenan G, Rutgeerts PJ. Extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn's disease: Response to infliximab (Remicade) in the ACCENT I trial through 30 weeks. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:A26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman HJ. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum in 50 patients with Crohn's disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19:603–606. doi: 10.1155/2005/323914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tavarela Veloso F. Review article: skin complications associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 4:50–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleisher M, Rubin S, Levine A, Burns A, Jacksonville FL. Infliximab in the treatment of steroid refractory erythema nodosum of IBD. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(Suppl 1):A618. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wenzel J, Gerdsen R, Phillipp-Dormston W, Bieber T, Uerlich M. Topical treatment of pyoderma gangraenosum. Dermatology. 2002;205:221–223. doi: 10.1159/000065843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman S, Marion JF, Scherl E, Rubin PH, Present DH. Intravenous cyclosporine in refractory pyoderma gangrenosum complicating inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Incà R, Fagiuoli S, Sturniolo GC. Tacrolimus to treat pyoderma gangrenosum resistant to cyclosporine. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:783–784. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-9-199805010-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hohenleutner U, Mohr VD, Michel S, Landthaler M. Mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporin treatment for recalcitrant pyoderma gangrenosum. Lancet. 1997;350:1748. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eaton PA, Callen JP. Mycophenolate mofetil as therapy for pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:781–785. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheldon DG, Sawchuk LL, Kozarek RA, Thirlby RC. Twenty cases of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: diagnostic implications and management. Arch Surg. 2000;135:564–568; discussion 568-569. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.5.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohmori T, Yamagiwa A, Nakamura I, Nishikawa K, Saniabadi AR. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2101–2102. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Regueiro M, Valentine J, Plevy S, Fleisher MR, Lichtenstein GR. Infliximab for treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1821–1826. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MG, Shetty A, Bowden JJ, Williams JD, Griffiths CE, Forbes A, Greenwood R, Probert CS. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505–509. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.074815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trost LB, McDonnell JK. Important cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:580–585. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.031633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheon JH, Kim ES, Shin SJ, Kim TI, Lee KM, Kim SW, Kim JS, Kim YS, Choi CH, Ye BD, et al. Development and validation of novel diagnostic criteria for intestinal Behçet's disease in Korean patients with ileocolonic ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2492–2499. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casson DH, Eltumi M, Tomlin S, Walker-Smith JA, Murch SH. Topical tacrolimus may be effective in the treatment of oral and perineal Crohn's disease. Gut. 2000;47:436–440. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Felekis T, Katsanos K, Kitsanou M, Trakos N, Theopistos V, Christodoulou D, Asproudis I, Tsianos EV. Spectrum and frequency of ophthalmologic manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective single-center study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:29–34. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orchard TR, Chua CN, Ahmad T, Cheng H, Welsh KI, Jewell DP. Uveitis and erythema nodosum in inflammatory bowel disease: clinical features and the role of HLA genes. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:714–718. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hale S, Lightman S. Anti-TNF therapies in the management of acute and chronic uveitis. Cytokine. 2006;33:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fries W, Giofré MR, Catanoso M, Lo Gullo R. Treatment of acute uveitis associated with Crohn's disease and sacroileitis with infliximab. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:499–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suhler EB, Smith JR, Wertheim MS, Lauer AK, Kurz DE, Pickard TD, Rosenbaum JT. A prospective trial of infliximab therapy for refractory uveitis: preliminary safety and efficacy outcomes. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:903–912. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.7.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Danese S, Semeraro S, Papa A, Roberto I, Scaldaferri F, Fedeli G, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7227–7236. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i46.7227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cullen S, Chapman R. Sclerosing cholangitis - what to do? In: Irving P, Ramptom D, Shanahan F, et al., editors. Clinical dilemmas in inflammatory bowel disease. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. pp. 205–208. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Talwalkar JA, Lindor KD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:62–72. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200501000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loftus EV Jr, Harewood GC, Loftus CG, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Jewell DA, Sandborn WJ. PSC-IBD: a unique form of inflammatory bowel disease associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 2005;54:91–96. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.046615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]