Abstract

Objective: To undertake a systematic review and meta-analysis on the risk of repeat offending in individuals with psychosis and to assess the effect of potential moderating characteristics on risk estimates. Methods: A systematic search was conducted in 6 bibliographic databases from January 1966 to January 2009, supplemented with correspondence with authors. Studies that reported risks of repeat offending in individuals with psychotic disorders (n = 3511) compared with individuals with other psychiatric disorders (n = 5446) and healthy individuals (n = 71 552) were included. Risks of repeat offending were calculated using fixed- and random-effects models to calculate pooled odds ratios (ORs). Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were conducted to examine how risk estimates were affected by various study characteristics including mean sample age, study location, sample size, study period, outcome measure, duration of follow-up, and diagnostic criteria. Results: Twenty-seven studies, which included 3511 individuals with psychosis, were identified. Compared with individuals without any psychiatric disorders, there was a significantly increased risk of repeat offending in individuals with psychosis (pooled OR = 1.6, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.4–1.8), although this was only based on 4 studies. In contrast, there was no association when individuals with other psychiatric disorders were used as the comparison group (pooled OR = 1.0, 95% CI = 0.7–1.3), although there was substantial heterogeneity. Higher risk estimates were found in female-only samples with psychosis and in studies conducted in the United States. Conclusions: The association between psychosis and repeat offending differed depending on the comparison group. Despite this, we found no support for the findings of previous reviews that psychosis is associated with a lower risk of repeat offending.

Keywords: schizophrenia, psychotic disorders, crime, violence, review, meta-analysis

Introduction

With around 10 million prisoners worldwide,1 there are approximately 400 000 individuals with psychosis who are currently in custody.2 In the United States, this equates to around 80 000 individuals with psychosis, an estimate significantly more than all US public psychiatric hospital beds.3,4 One of the important questions this raises is whether psychosis is associated with repeat offending. As rates of reoffending are high across different countries,5–7 potentially modifiable determinants of recidivism have the potential to make a considerable contribution to public health and safety. One of these determinants is the improvement in the care and management of prisoners and offenders with schizophrenia and other psychoses. Furthermore, the number of forensic psychiatric inpatients has been growing markedly in many Western countries and other countries, including China,8,9 and risk assessment and management of patients with severe mental illness are increasing priorities for mental health services.10

Despite robust evidence demonstrating an association between psychosis and violent outcomes,11 particularly homicide,12 it remains uncertain whether there is an association between psychosis and repeat offending. A meta-analysis from 1998 concluded that psychosis was inversely related to re-offending,13 and, in keeping with this, some violence risk assessment instruments have included major mental illness as a protective factor.14 However, more recent evidence in larger samples has found that schizophrenia is not protective. A recent study of 79 211 prisoners found associations between psychosis and the number of repeat incarcerations in a dose-response manner.15 Another study of community offenders found no association between being diagnosed with schizophrenia and repeat violent offending.16 Recent reviews have been descriptive and not quantitatively synthesized the evidence or explored sources of heterogeneity.17,18 Therefore, we have undertaken a systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk of repeat offending in patients with psychotic disorders.

Methods

Studies of the association of psychotic disorders and criminal recidivism were sought by searches of computer-based databases (Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, Cinahl, US National Criminal Justice Reference System, and Web of Science) from January 1, 1966, to January 31, 2009. We used combinations of keywords relating to psychotic disorders (eg, psychotic, psychos*, and schiz*) and criminal recidivism (eg, recidi*, reoffend*, repeated offend*, rearrest, reconvict*, reincarerat*, revoke*, relapse, failure, and recur*). To improve our search, the terms mental disorder*, mental illness*, and psychiatric disorder* were also used, combined with the search terms for criminal recidivism. These were supplemented with scanning of article reference lists and correspondence with authors. We included case-control studies (including cross-sectional surveys) and cohort studies, which investigated the risk of criminal recidivism in persons with psychotic disorders, compared with individuals without psychiatric disorders or patients with other psychiatric disorders. We included articles in all languages. Studies were excluded if they (1) involved assessment of psychotic disorders based solely on self-report questionnaires;19,20 (2) were restricted to single category of crime, for instance, repeat homicide,21,22 sexual reoffending,23 repeat fire setting,24 or spousal assault recidivism25; (3) investigated inpatient violence;26,27 and (4) did not provide information that allowed for the calculation of odds ratio (OR).28

A standardized form was used to extract data from the studies. Numbers of participants with or without psychotic disorders by criminal recidivism status were extracted for each article. The following information was recorded and coded according to a fixed protocol: study design, study period, geographical location of the study, diagnostic tool, comparison group, definition of cases, method of ascertainment, duration of follow-up, institutional setting, comorbidity with substance abuse, outcome measure, and descriptive statistics of the sample (eg, age and sex distribution). Data were extracted and cross-checked independently by the 2 authors. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and if necessary by contacting authors of studies.

ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the risk of criminal recidivism in psychotic disorders compared with control subjects were combined using meta-analysis, with the data presented in forest plots. The percentage of heterogeneity was estimated using Cochran Q (reported with a χ2-value and P value) and Higgins I2. The former examines the null hypothesis that all studies are evaluating the same effect29 and the latter describing the percentage of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance and presented with 95% CIs.29 I2, unlike Q, does not inherently depend on the number of studies considered. For I2, the values of 25%, 50%, and 75% indicated low, moderate, and high levels of heterogeneity, respectively. When the heterogeneity among studies was high, random-effects models were used. Random-effects models incorporate an estimate of between-study heterogeneity into the calculation of the common effect and give a relatively similar weight to studies of different size.30 If the heterogeneity was not high, fixed-effects estimates of pooled ORs were calculated. Fixed-effects models average the summary statistics, weighting them according to a measure of the quantity of information they contain, and hence the estimates are weighted by study size.30 Potential sources of heterogeneity were investigated further by subgroup analysis and meta-regression. The characteristics investigated were study design (cohort vs case-control), study period (before 1990 vs 1990 and after), geographical location of the study (United States vs other countries), gender (male/female/mixed), mean age (older than 30 y vs 30 y or younger, and as a continuous variable in metaregression), diagnostic tool (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders vs International Classification of Diseases), institutional setting (psychiatric hospital vs prison), follow-up period (less than 6 y/6–10 y/more than 10 y), comparison group (control subjects without psychiatric disorders vs a comparison group who had other psychiatric disorders), outcome measure (violent recidivism vs any criminal recidivism [including violent outcomes]), and the definition of cases (schizophrenia vs schizophrenia and other psychoses). There was insufficient information in the included studies to make a comparison between schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia psychoses or violent outcomes compared with nonviolent outcomes. One study provided comparison data from both healthy control subjects and patients with other psychiatric disorders,31 and we used the data from healthy control subjects in order to avoid duplication. Meta-regression was not conducted if there were less than 10 studies.32 The influence of individual studies on the summary effect was explored using an influence analysis, in which meta-analysis estimates are computed omitting one study at a time.33 In addition, publication bias was tested by funnel plot asymmetry using the rank correlation method (Begg's method)34 and weighted regression approach (Egger's test).35 All the analyses were performed in STATA statistical software package, version 10.0 (Statacorp, College Station, TX 2007)36.

Results

Study Characteristics

The final sample consisted of 27 studies that included 3511 individuals with psychotic disorders reported in 24 publications.14–16,31,37–56 Three studies reported male and female samples separately.40,41,50 Of the case subjects with psychosis, 1067 (30.4%) were repeat offenders. Overall, these were compared with 76 998 control subjects, of whom 29 767 (38.7%) were criminal recidivists. Publications were from 10 countries: 9 studies from the United States (1252 case subjects, 35.7% of the total number of the case subjects),15,38,39,41,42,44,52,54 7 from the United Kingdom (1038 case subjects, 29.7%),37,40,46,50,51 4 from Canada (322 case subjects, 9.0%),14,43,47,48 and 1 each from Japan (315 case subjects, 8.9%),56 Sweden (248 case subjects, 7.0%),16 France (229 case subjects, 6.5%),55 Brazil (50 case subjects, 1.4%),45 Italy (43 case subjects, 1.2%),49 Germany (12 case subjects, 0.3%),31 and Belgium (2 case subjects, 0.1%).53 Register-based studies were the source of all outcome data. All investigations were conducted after 1974 (for details of the studies included, see table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studies Reporting on Risk of Recidivism in Patients With Psychotic Disorders

| Study Name | Region | Study Type | No. of Case Subjects | No. of Control Subjects | Diagnostic Criteria | Mean Age (y) | Gender | Definition of Cases | Institutional Setting | Follow-up (y) | Comparison Group | Definition of Outcomes |

| Ganzer and Sarason41 (M) | United States | Case-control | 14 | 86 | NA | 15.3 | Male | Psychosis | Juvenile rehabilitation institution | 2 | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Ganzer and Sarason41 (F) | United States | Case-control | 5 | 95 | NA | 14.7 | Female | Psychosis | Juvenile rehabilitation institution | 2 | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Payne et al46 | United Kingdom | Cohort | 93 | 31 | NA | NA | Mixed | Schizophrenia | General psychiatric or special (secure) hospital | NA | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Quinsey et al47 | Canada | Cohort | 38 | 53 | NA | 32 | Male | Psychosis | Maximum secure hospital | NA | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Tennent and Way51 | United Kingdom | Cohort | 32 | 374 | NA | NA | Male | Schizophrenia | Special (secure) hospital | 8.8 | Other PD | Violent recidivism |

| Yesavage et al55 | France | Cohort | 229 | 981 | DSM-III | NA | Mixed | Schizophrenia | Special (secure) hospital | 22 | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Bieber et al39 | United States | Cross-sectional | 48 | 84 | NA | NA | Mixed | Psychosis | NGRI (hospitalized) | NA | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Komer and Galbraith43 | Canada | Cohort | 15 | 15 | NA | 28.4 | Mixed | Schizophrenia | Held on warrant in community | 14.8 | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Bailey and Macculloch37 | United Kingdom | Cohort | 47 | 65 | DSM-III-R | >30 | Male | Schizophrenia | Special (secure) hospital | 3.28 | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Harris et al14 | Canada | Cohort | 143 | 475 | DSM-III | 27 | Male | Schizophrenia | Half from secure hospital and half were assessed briefly in secure hospital | 6.8 | Other PD | Violent recidivism |

| Russo49 | Italy | Cohort | 43 | 48 | NA | 40 | Male | Psychosis | Maximum secure hospital | 5 | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Rice and Harris48 | Canada | Cohort | 126 | 321 | DSM-III | >30 | Male | Schizophrenia | Half from maximum secure hospital and half from prison | 6.5 | Other PD | Violent recidivism |

| Harris and Koepsell42 | United States | Cohort | 12 | 24 | NA | NA | Mixed | Psychosis | Psychiatric hospital | NA | No PD | All recidivism |

| Ventura et al52 | United States | Cohort | 42 | 133 | DSM-III-R | 28.7 | Mixed | Schizophrenia | Jail | 3 | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Singleton et al50 (M) | United Kingdom | Cohort | 49 | 1058 | DSM-IV | NA | Male | Psychosis | Prison | NA | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Singleton et al50 (F) | United Kingdom | Cohort | 56 | 513 | DSM-IV | NA | Male | Psychosis | Prison | NA | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Moscatello45 | Brazil | Cross-sectional | 50 | 50 | ICD-10 | 38.9 | Male | Schizophrenia | Secure hospital | NA | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Vermeiren et al53 | Belgium | Cohort | 2 | 46 | DSM | 16 | Male | Psychosis | NA | 2 | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Lee44 | United States | Cohort | 39 | 86 | NA | >30 | Mixed | Schizophrenia | State hospital or court | 11 | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Bertman-Pate et al38 | United States | Cohort | 48 | 71 | DSM-IV | 38 | Mixed | Schizophrenia | Hospital or jail | NA | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Stadtland and Nedopil31 | Germany | Case-control | 12 | 36 | ICD-10 | NA | Mixed | Schizophrenia | NA | 8.5 | No PD | All recidivism |

| Coid et al40 (M) | United Kingdom | Cohort | 690 | 422 | DSM-III-R | 31.6 | Male | Schizophrenia | Medium secure hospital | 6.2 | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Coid et al40 (F) | United Kingdom | Cohort | 71 | 97 | DSM-III-R | 31.6 | Female | Schizophrenia | Medium secure hospital | 6.2 | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Yoskikawa et al56 | Japan | Cohort | 315 | 174 | DSM-IV-TR | NA | Mixed | Schizophrenia | NGRI (hospitalized) | NA | Other PD | Violent recidivism |

| Grann et al16 | Sweden | Cohort | 248 | 159 | DSM-III | 35.7 | Mixed | Schizophrenia | Community-based sanctions | 4.8 | No PD | Violent recidivism |

| Vitacco et al54 | United States | Cohort | 195 | 168 | DSM-IV | 41 | Mixed | Psychosis | NGRI (released to community after a brief assessment) | 2.85 | Other PD | All recidivism |

| Baillargeon et al15 | United States | Cohort | 849 | 71 333 | DSM-IV | NA | Mixed | Schizophrenia | Prison | 6 | No PD | All recidivism |

Note: M = male; NA = information not available; PD = psychiatric disorders; F = female; DSM-III = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Third Edition); DSM-III-R = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Third Edition Revised); DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition); ICD-10 = International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; DSM-IV-TR = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition, Text Revision); NGRI = not guilty by reason of insanity.

Risk Estimates by Comparison Group

There were 2 comparison groups—those with other psychiatric disorders and control subjects without any such disorders. The first comparison group included 23 studies with 5446 individuals with other psychiatric disorders, of whom 2104 (38.6%) were repeat offenders.14,37–41,43–56 In these studies, the rate of repeat offending in those with psychotic disorders was 23.5% (562 recidivists among 2390 case subjects). There were 4 studies with individuals without any mental disorders as control subjects. These amounted to 71 552 control subjects, of whom 27 663 (38.7%) reoffended.15,16,31,42 The rate of repeat offending in the case subjects with psychotic disorders in these 4 studies was 45.0% (505/1121).

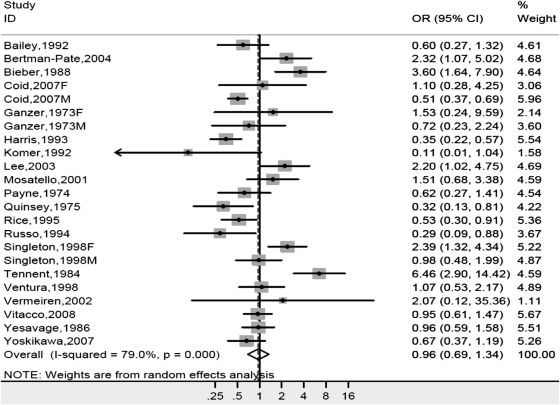

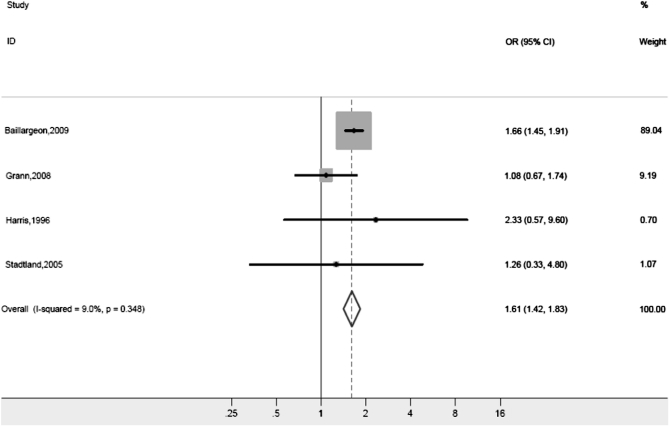

As there was substantial heterogeneity in risk estimate between the studies ( P < .001, I2 = 83.0%), we analyzed these data separately by comparison group. Compared with individuals with other mental disorders, there was no significant risk of criminal recidivism in individuals with psychosis (pooled random-effects OR of 1.0, 95% CI = 0.7–1.3). There was high heterogeneity between the studies ( P < .001, I2 = 79%) (figure 1). Compared with control subjects without psychiatric disorders, the risk of criminal recidivism was increased in those with psychotic disorders. We found a pooled fixed-effects OR of 1.6 (95% CI = 1.4–1.8) with low heterogeneity among studies ( P = .35, I2 = 9.0%) (figure 2). As the heterogeneity was high in the first of these analyses, possible differences between risk estimates by various characteristics were further investigated.

Fig. 1.

Risk Estimate for Repeat Offending in Psychotic Disorders Compared With Individuals With Other Psychiatric Disorders. Note: OR = odds ratio

Fig. 2.

Risk Estimate for Repeat Offending in Psychotic Disorders Compared With Control Subjects Without Psychiatric Disorders. Note: OR = odds ratio. Weights are from fixed-effects model.

Twenty studies provided comparison data for individuals with personality disorders.16,31,37,38,40–43,45,47,49–52,54,55 Compared with personality disorder, individuals with psychosis had a lower risk of repeat offending (OR = 0.5, 95% CI = 0.4–0.7, with moderate heterogeneity: P < .001, I2 = 63.0%). Nine studies provided comparison data for individuals with substance use disorders.16,31,37,38,47,51,53–55 Those with psychosis had a similar risk of repeat offending with an OR of 0.9 (95% CI = 0.5–1.4) with moderate heterogeneity ( P < .001, I2 = 72.0%). Four studies provided comparison data from patients with depression,15,16,31,51 and psychosis was associated with a higher risk of repeat offending (OR = 1.9, 95% CI = 0.9–4.0, with high heterogeneity between studies [ P < .001, I2 = 85.3%]). Three studies provided data from patients with mental retardation/learning disability,31,38,55 and the risk of recidivism was similar to those with psychosis (OR = 1.2, 95% CI = 0.3–4.4, with moderate heterogeneity: P = .01, I2 = 77.9%).

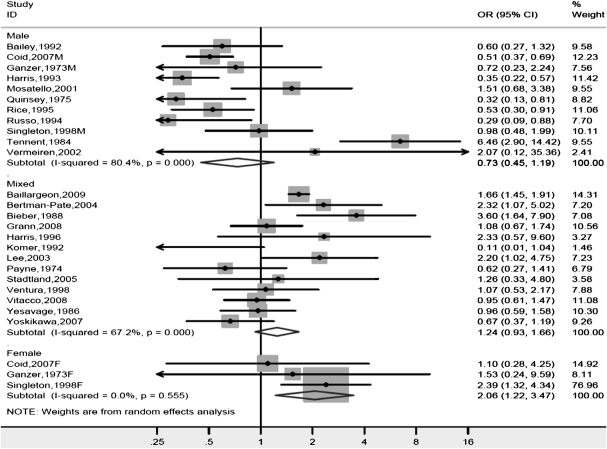

Gender

Significant differences in risk estimates were found between genders. When the analysis was limited to studies where persons with other psychiatric disorders were control subjects, the OR was 0.7 (95% CI = 0.5–1.2) in males, whereas it was 2.1 (95% CI = 1.2–3.5) in females. Studies with mixed gender samples reported an OR of 1.2 (95% CI = 0.9–1.7) (figure 3). Investigations with healthy control subjects did not provide a breakdown by gender.

Fig. 3.

Risk Estimate for Repeat Offending in Psychotic Disorders by Gender Compared With Individuals With Other Psychiatric Disorders. Note: OR = odds ratio.

Region

When all reports were included, we found significant differences in risk estimates by study region. Studies from the United States reported an OR of 1.6 (95% CI = 1.2–2.1), whereas investigations from the rest of the world reported an OR of 0.8 (95% CI = 0.6–1.2). These differences were less pronounced when stratified by comparison group—when compared with individuals with other mental disorders, an OR of 1.5 (95% CI = 1.0–2.4) was reported in US-based studies compared with an OR of 0.8 (95% CI = 0.5–1.2) in others. When analysis was limited to investigations with healthy control subjects, the US-based studies reported an OR of 1.7 (95% CI = 1.5–1.9), whereas for the others, the OR was 1.1 (95% CI = 0.7–1.7).

Institutional Setting

Differences in risk estimates depending on the setting (hospital vs. prison) of individuals with psychosis were examined in studies where information was available. A nonsignificant higher risk of repeat offending was found in individuals with psychosis released from prison (OR = 1.5, 95% CI = 1.3–2.1, with low heterogeneity [ P = .16, I2 = 40.5%]), than in patients discharged from psychiatric hospital (OR = 0.9, 95% CI = 0.6–1.5, with high heterogeneity [ P < .001, I2 = 80.8%]).

Other Characteristics

There were no significant differences in risk estimates for the other characteristics examined including study period, sample size, diagnostic criteria, mean age, definition of diagnosis, study location, outcome measure, study type, and duration of follow-up, in the studies where information was available (table 2). Studies of violent recidivism reported an OR of 1.0 (95% CI = 0.5–1.9), compared with other investigations of any criminal recidivism (which included violent outcomes) that reported an OR of 1.1 (95% CI = 0.8–1.5).

Table 2.

Risk Estimates for Criminal Recidivism in Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses by Sample or Study Characteristics

| Sample or Study Characteristics | Number of Studies | Number of Case Subjects With Psychosis | OR (95% CI) |

| Type of psychosis | |||

| Schizophrenia | 17 | 871 | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) |

| Schizophrenia and other psychoses | 10 | 196 | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) |

| Study period | |||

| Study conducted before 1990 | 12 | 186 | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) |

| Study conducted in 1990 or after | 15 | 881 | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) |

| Diagnostic criteriaa | |||

| DSM criteria | 15 | 891 | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) |

| ICD criteria | 2 | 37 | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) |

| Design | |||

| Case-control | 5 | 68 | 1.7 (0.9–3.0) |

| Cohort | 22 | 999 | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) |

| Mean ageb | |||

| 30 y or younger | 6 | 59 | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) |

| Older than 30 y | 11 | 348 | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) |

| Number of cases | |||

| <100 cases | 17 | 242 | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) |

| ≥100 cases | 10 | 825 | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) |

| Outcome | |||

| Violent recidivism | 6 | 177 | 1.0 (0.5–1.9) |

| Any criminal recidivism | 21 | 890 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) |

| Duration of follow-up (y)c | |||

| <6 | 8 | 596 | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) |

| 6–10 | 7 | 1923 | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| >10 | 3 | 283 | 1.0 (0.5–2.7) |

Note: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ICD, International Classification of Diseases.

Number of studies and case subjects differ in this analysis because 10 studies39,41–44,46,47,49,51 did not provide information on diagnostic criteria.

Meta-regression

Meta-regression confirmed the findings of the subgroup analyses and found that the heterogeneity was partly explained by region (studies conducted in the United States reported a higher risk estimate; β = −.68, SE[β] = 0.30, P = .03) and gender (studies with female samples reported a higher risk estimate; β = .48, SE[β] = 0.23, P = .05). When limiting the meta-regression to studies that used other mental disorders as controls, nonsignificant associations were found with region (US-based studies reported a higher risk estimate; β = −.68, SE[β] = 0.36, P = .07) and gender (studies with female samples reported a higher risk estimate; β = .44, SE[β] = 0.25, P = .09).

Publication Bias and Influence of Individual Studies

There was no evidence for publication bias in studies with patients with other psychiatric disorders as control subjects using the weighted regression (Egger) method (t = 1.19, P = .25) or the rank correlation (Begg) method (P = .48). Similarly, no publication bias was evident in studies with healthy individuals as control subjects when using either Egger (t = −0.62, P = .59) or Begg method (P = .34). Influence analysis revealed that there was no individual study with significant influence on the overall risk estimate for criminal recidivism in reports with patients with other psychiatric disorders as control subjects, which means that the omission of any single study made little or no difference of the summary risk estimate. Analysis of investigations with healthy control subjects found that study by Baillargeon et al15 had a significant influence on the overall risk estimate. When this study was omitted, the OR was lower than when it was included (OR = 1.2, 95% CI = 0.8–1.8, vs OR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.4–1.8). The omission of any other single report made little or no difference to the summary risk estimate.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 27 studies from 10 countries that examined the risk of repeat offending in 3511 individuals with psychosis. There were 3 main findings. First, there was a modest association between psychosis and repeat offending when individuals with psychosis were compared with general population control subjects who did not have any mental disorders. Second, the risk of repeat offending differed according to the comparison group, and there was no association between psychosis and reoffending when persons with other psychiatric disorders were used as control subjects. Third, some of the heterogeneity across the studies was explained by the proportion of women with psychosis in the research sample and whether the investigation was US based.

Our main finding is in contrast to an influential meta-analysis that reported an inverse association with the psychoses13 and contributed to the development of widely used violence risk assessment instruments that rated any major mental illness as a protective factor for future violence risk.14 One of the possible explanations for the present review's contrasting finding is that the previous meta-analysis included only studies where other psychiatric disorders were used as comparison.

The finding in the present review that individuals with psychosis are associated with a higher risk of reoffending does not necessarily imply a causative role or that those such clinical factors can make an important contribution to risk prediction. It is possible that the association is confounded by sociodemographic, criminal history, and other clinical factors, such as substance abuse, which have not been adequately adjusted for in the individual studies that make up this review. In addition, research in patients leaving high secure hospital,57 general psychiatric patients,58 and community offenders16 suggests that diagnostic factors make a small contribution to risk prediction. However, as this contribution is potentially treatable unlike sociodemographic and criminal history factors, its role in risk assessment and management deserves careful consideration and further research. As rates of reoffending were around 30% in those with psychotic disorders, any risk reduction is likely to lead to considerably less criminality in absolute terms.

Women with psychotic disorders appeared to be at higher risk for repeat offending compared with women with other psychiatric disorders than the corresponding comparison in men. This is in keeping with risk estimates for any violence in schizophrenia and other psychoses where women also have higher risk estimates.11 Theoretical explanations for this difference include the view that females who develop antisocial behavior surmount a threshold of risk higher than that of males and are therefore more severely afflicted.59

Studies conducted in the United States reported higher risk estimates than investigations from the rest of the world. This finding lends some support to the view that national differences may play an important role in determining the association between mental illness and crime.60 With regard to reoffending, national differences in the efficacy of community-based mental health programs and prison discharge planning programs may be relevant. Some writers have argued that this should lead to greater public policy and public health initiatives to impact on criminal recidivism.61 It is also possible that due to pressures on US prison health care, where only half of all intimates with mental illness receive treatment,62 prisoners with psychosis are less likely to receive treatment than the other countries included in our review. In addition, it is possible that the relative lack of development of community psychiatric services in the United States contributes to higher rates of repeat offending.63 The role of treatment is further suggested by studies on homicide offenders12 and our tentative finding that those leaving psychiatric hospitals had lower risks of recidivism than individuals with psychotic disorders leaving prison.

There were several nonsignificant findings for different study characteristics including study date, diagnostic criteria, duration of follow-up, and age as a dichotomous variable (above and below 30 y). Cohort studies found a nonsignificant lower risk of criminal recidivism than in cross-sectional or case-control studies. A major advantage of cohort designs is that it can potentially demonstrate a temporal sequence between exposure and outcome,64 and future research using longitudinal designs would be worthwhile.

Limitations in the present review include the lack of information on potential confounders. A recent review found that individuals with schizophrenia and comorbid substance use disorders have increased risk of violence11 and other work has demonstrated that substance use disorders are highly prevalent in individuals with schizophrenia.65 In our study, the effect of such comorbidity was not calculated as no study provided data for risk in psychotic disorder with substance use disorder and without separately. Similarly, the influence of comorbidity of other psychiatric disorders was not investigated because of limited data. Personality disorders are likely to be important in this regard.66 Also, most of the studies did not take into account other factors. An offender's sociodemographic background such as social class, educational history, current employment status, and homelessness has been shown to be associated with criminal behavior in psychotic disorders.67,68 Therefore, it is likely that the risk estimates reported in this review overestimate the association between psychotic disorders and criminal recidivism. In addition, the clinical utility of the category “other psychiatric disorders” was limited as it included heterogeneous disorders with different risks of repeat offending. We explored this and found that when compared with samples with high rates of personality disorder, individuals with psychosis had lower risks of repeat offending. When compared with depression, individuals with psychosis had a higher risk. This underlines the importance of taking into account diagnostic information in comparison groups. Furthermore, only one study in the systematic review was from a non-Western country (Japan56), and future work could analyze the association between psychosis and reoffending in other settings.

In conclusion, this systematic review has found that individuals with psychotic disorders have a modestly higher risk of repeat offending compared with persons without any psychiatric disorders and a similar risk compared with individuals other psychiatric disorders. As the absolute numbers of prisoners with psychosis are large and continuing to rise worldwide, improvements to their treatment and management in custody and on release have the potential to make a considerable impact in public health terms.69,70 Furthermore, as rates of reoffending are high throughout Western countries, any interventions to manage this risk have the potential to make a significant contribution to public safety.

Acknowledgments

The following investigators kindly provided additional information from their studies: Dr Jacques Baillargeon, University of Texas, United States; Prof Tony Maden, Imperial College, University of London, United Kingdom; Dr Sandy Simpson, University of Auckland, New Zealand; and Dr Ming Yang, University of London, United Kingdom. Ms Maeve Ladbrooke, Warneford Hospital Library, Oxford, assisted in obtaining articles.

References

- 1.Walmsley R. World Prison Population List. 8th ed. London, UK: International Centre for Prison Studies; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fazel S, Danesh J. Serious mental disorder in 23000 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet. 2002;359:545–550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07740-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geller JL, Guzdfski S, Lauterbach M. The ins and outs of 200 years of psychiatric hospitals in the United States. In: Ovsiew F, Munich RL, editors. Principles of Inpatient Psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torrey EF. Jails and prisons–America's new mental hospitals. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1611–1613. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.12.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumer E, Wright R, Kristinsdottir K, Gunnlaugsson H. Crime, shame and recidivism: the case of Iceland. Br J Criminol. 2002;41:40–59. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Home Office Research Development and Statistics Department. Crime in England and Wales 2007/2008. London, UK: Home Office; 2009. http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/crimeew0708.html. Accessed October 27, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langan P, Lewin D. Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 1994. Washington, DC: Department of Justice; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu Y, Hu Z. More attention should be paid to schizophrenic patients with risk of violent offences. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:592–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Priebe S, Frottier P, Gaddini A, et al. Mental health care institutions in nine European countries, 2002 to 2006. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:570–573. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.5.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar S, Simpson AI. Application of risk assessment for violence methods to general adult psychiatry: a selective literature review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:328–335. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, Geddes JR, Grann M. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielssen O, Large M. Rates of homicide during the first episode of psychosis and after treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:702–712. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonta J, Law M, Hanson K. The prediction of criminal and violent recidivism among mentally disordered offenders: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1998;123:123–142. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.123.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris G, Rice M, Quinsey L. Violent recidivism of mentally disordered offenders: the development of a statistical prediction instrument. Crim Justice Behav. 1993;20:315–335. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baillargeon J, Binswanger IA, Penn JV, Williams BA, Murray OJ. Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: the revolving prison door. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:103–109. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grann M, Danesh J, Fazel S. The association between psychiatric diagnosis and violent re-offending in adult offenders in the community. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joyal CC, Dubreucq J, Gendron C, Millaud F. Major mental disorders and violence: a critical update. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2007;3:33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamberti JS. Understanding and preventing criminal recidivism among adults with psychotic disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:773–781. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker JS, Morton TL, Lingefelt ME, Johnson KS. Predictors of serious and violent offending by adjudicated male adolescents. N Am J Psychol. 2005;7:407–418. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valliant PM, Gristey C, Pottier D, Kosmyna R. Risk factors in violent and nonviolent offenders. Psychol Rep. 1999;85:675–680. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1999.85.2.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Putkonen H, Komulainen EJ, Virkkunen M, Eronen M, Lonnqvist J. Risk of repeat offending among violent female offenders with psychotic and personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:947–951. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiihonen J, Hakola P. Psychiatric disorders and homicide recidivism. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:436–438. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langstrom N, Sjostedt G, Grann M. Psychiatric disorders and recidivism in sexual offenders. Sex Abuse. 2004;16:139–150. doi: 10.1177/107906320401600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Repo E, Virkkunen M. Criminal recidivism and family histories of schizophrenic and nonschizophrenic fire setters: comorbid alcohol dependence in schizophrenic fire setters. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1997;25:207–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grann M, Wedin I. Risk factors for recidivism among spousal assault and spousal homicide offenders. Psychol Crime Law. 2002;8:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noble P, Rodger S. Violence by psychiatric in-patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155:384–390. doi: 10.1192/bjp.155.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owen C, Tarantello C, Jones M, Tennant C. Repetitively violent patients in psychiatric units. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:1458–1461. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.11.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM. Does psychiatric disorder predict violent crime among released jail detainees: a six-year longitudinal study. Am Psychol. 1994;49:335–342. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins J, Thompson S, Deeks J, Altman D. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. In: Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG, editors. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context. BMJ Publishing Group; 2001. pp. 294–312. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stadtland C, Nedopil N. Psychiatrische erkrankungen und die prognose krimineller rückfälligkeit [Psychiatric disorders and the prognosis for criminal recidivism] Nervenarzt. 2005;76:1402–1411. doi: 10.1007/s00115-004-1808-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson SG, Higgins JPT. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med. 2002;21:1559–1573. doi: 10.1002/sim.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sterne J, Bradburn MJ, Egger M. Meta-analysis in Stata. In: Egger M, Altman D, editors. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context. London, UK: BMJ; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Begg C, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:979–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Egger M, Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 10. 2007. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailey J, Macculloch M. Characteristics of 112 cases discharged directly to the community from a new special hospital and some comparison of performance. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 1992;3:91–112. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertman-Pate LJ, Burnett DM, Thompson JW, Calhoun CJ, Jr, Deland S, Fryou RM. The New Orleans Forensic Aftercare Clinic: a seven year review of hospital discharged and jail diverted clients. Behav Sci Law. 2004;22:159–169. doi: 10.1002/bsl.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bieber SL, Pasewark RA, Bosten K, Steadman HJ. Predicting criminal recidivism of insanity acquittees. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1988;11:105–112. doi: 10.1016/0160-2527(88)90024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coid J, Hickey N, Kahtan N, Zhang T, Yang M. Patients discharged from medium secure forensic psychiatry services: reconvictions and risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:223–229. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.018788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ganzer VJ, Sarason IG. Variables associated with recidivism among juvenile delinquents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1973;40:1–5. doi: 10.1037/h0034012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris V, Koepsell TD. Criminal recidivism in mentally ill offenders: a pilot study. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1996;24:177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Komer B, Galbraith D. Recidivism among individuals detained under a warrant of the Lieutenant-Governor living in the community. Can J Psychiatry. 1992;37:694–698. doi: 10.1177/070674379203701004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee DT. Community-treated and discharged forensic patients: an 11-year follow-up. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2003;26:289–300. doi: 10.1016/S0160-2527(03)00039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moscatello R. Recidiva criminal em 100 internos do Manicômio Judiciário Franco da Rocha [Criminal recurrence among 100 inmates of Franco da Rocha forensic hospital] Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2001;23:34–35. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Payne C, McCabe S, Walker N. Predicting offender-patients’ reconvictions. Br J Psychiatry. 1974;125:60–64. doi: 10.1192/bjp.125.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quinsey VL, Warneford A, Pruesse M, Link N. Released oak ridge patients: a follow-up study of review board discharges. Br J Criminol. 1975;15:264–270. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rice ME, Harris GT. Psychopathy, schizophrenia, alcohol abuse, and violent recidivism. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1995;18:333–342. doi: 10.1016/0160-2527(95)00015-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russo G. Follow-up of 91 mentally ill criminals discharged from the maximum security hospital in Barcelona P.G. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1994;17:279–301. doi: 10.1016/0160-2527(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singleton N, Meltzer H, Gatward R. Psychiatric Morbidity Among Prisoners in England and Wales. London, UK: Stationery Office; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tennent G, Way C. The English special hospital–a 12-17 year follow-up study: a comparison of violent and non-violent re-offenders and non-offenders. Med Sci Law. 1984;24:81–91. doi: 10.1177/002580248402400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ventura LA, Cassel CA, Jacoby JE, Huang B. Case management and recidivism of mentally ill persons released from jail. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:1330–1337. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.10.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vermeiren R, Schwab-Stone M, Ruchkin V, De Clippele A, Deboutte D. Predicting recidivism in delinquent adolescents from psychological and psychiatric assessment. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43:142–149. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.30809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vitacco MJ, Van Rybroek GJ, Erickson SK, et al. Developing services for insanity acquittees conditionally released into the community: maximizing success and minimizing recidivism. Psychol Serv. 2008;5:118–125. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yesavage JA, Benezech M, Larrieu-Arguille R, et al. Recidivism of the criminally insane in France: a 22-year follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 1986;47:465–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshikawa K, Taylor PJ, Yamagami A, et al. Violent recidivism among mentally disordered offenders in Japan. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2007;17:137–151. doi: 10.1002/cbm.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buchanan A, Leese M. Quantifying the contributions of three types of information to the prediction of criminal conviction using the receiver operating characteristic. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:472–478. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.011122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wootton L, Buchanan A, Leese M, et al. Violence in psychosis: estimating the predictive validity of readily accessible clinical information in a community sample. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.12.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA. Sex Differences in Antisocial Behaviour: Conduct Disorder, Delinquency, and Violence in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Appelbaum PS. Violence and mental disorders: data and public policy. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1319–1321. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.8.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Warren J. One in 100: Behind Bars in America 2008. Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trusts; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ditton PM. Mental Health and Treatment of Inmates and Probationers. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Torrey EF. Insanity Offense: How America's Failure to Treat the Seriously Mentally Ill Endangers. New York, NY: Norton, W.W. & Company; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fletcher RW, Fletcher SW, editors. Clinical epidemiology: The essentials. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fazel S, Grann M, Carlström E, Lichtenstein P, Långström N. Risk factors for violent crime in schizophrenia: a national cohort study of 13,806 patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:362–369. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moran P, Walsh E, Tryer P, Burns T, Creed F, Fahy T. Impact of comorbid personality disorder on violence in psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:129–134. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McGuire JF, Rosenheck RA. Criminal history as a prognostic indicator in the treatment of homeless people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:42–48. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Essock SM, et al. The social-environmental context of violent behavior in persons treated for severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1523–1531. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cole TB, Glass RM. Mental illness and violent death: major issues for public health. JAMA. 2005;294:623–624. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Glaser JB, Greifinger RB. Correctional health care: a public health opportunity. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:139–145. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-2-199301150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]