Abstract

Burkholderia pseudomallei, the causative agent of melioidosis, is endemic in northeastern Thailand. Population-based disease burden estimates are lacking and limited data on melioidosis exist from other regions of the country. Using active, population-based surveillance, we measured the incidence of bacteremic melioidosis in the provinces of Sa Kaeo (eastern Thailand) and Nakhon Phanom (northeastern Thailand) during 2006–2008. The average annual incidence in Sa Kaeo and Nakhon Phanom per 100,000 persons was 4.9 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 3.9–6.1) and 14.9 (95% CI = 13.3–16.6). The respective population mortality rates were 1.9 (95% CI = 1.3–2.8) and 4.4 (95% CI = 3.6–5.3) per 100,000. The case-fatality proportion was 36% among those with known outcome. Our findings document a high incidence and case fatality proportion of bacteremic melioidosis in Thailand, including a region not traditionally considered highly endemic, and have potential implications for clinical management and health policy.

Melioidosis, caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei, is endemic in the northern Territory of Australia and northeastern Thailand.1 The Thailand National Annual Epidemiology Surveillance Report recorded a nationwide incidence of 1.74 cases per 100,000 and a population mortality rate (PMR) of 0.01 per 100,000 in 2008.2 These figures likely underestimate the true burden, caused by the passive nature of national surveillance and limited detection capabilities in many parts of Thailand. Few incidence estimates based on surveillance systems with active case finding and reporting are available from Thailand. A 1994 study with active case finding estimated the melioidosis incidence in one northeastern province as 4.4 cases per 100,000.3 Two more recent studies of culture-confirmed melioidosis cases from the same region each found a higher average annual incidence (9.974 and 12.75 cases per 100,000) and PMR (8.6 deaths per 100,000).5 Melioidosis is a severe disease with a case fatality proportion (CFP) of 40–50%.5,6 Septicemia is the most severe form with highest associated mortality.7,8 Previous studies on incidence and mortality in Thailand have included only cases identified at provincial hospitals, whereas diagnostic capacity at lower level facilities can be lacking, meaning cases outside of referral centers are likely missed. We estimated the incidence and CFP of bacteremic melioidosis in two Thailand provinces where ongoing pneumonia surveillance is conducted9 and all hospitals had access to automated culture systems, including one eastern province, where previously limited data were available.10,11

Laboratory-based surveillance for bloodstream infections was established in two provinces as part of a collaboration between the Thailand Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, USA). Automated microbial detection systems (BacT/ALERT 3D, bioMérieux Inc., Durham, NC) were implemented in Sa Kaeo ([SK], eastern province bordering Cambodia, population ∼526,000) in May 2005 and Nakhon Phanom ([NP], northeastern province bordering Laos, population ∼734,000) in November 2005.12 Cultures were collected at clinician discretion, but were encouraged among patients admitted with suspected pneumonia or sepsis in all hospitals, including two provincial hospitals (307 and 341 beds) and 18 district/military hospitals (30 to 140 beds). Two blood culture bottles were inoculated for each patient, a standard bottle to support aerobic growth (BacT/ALERT FA [FA] for ages ≥ 5 years and BacT/ALERT PF [PF] for ages < 5 years) and a bottle to enhance growth of mycobacteria and other fastidious organisms (BacT/ALERT MB [MB]). Blood cultures from district/military hospitals were transported to provincial hospitals for processing within 24 hours. Positive cultures were processed using standard biochemical methods to identify B. pseudomallei and were confirmed by the Thailand National Institute of Health. Medical records were reviewed to determine patient outcome. Patients who were discharged in moribund condition to die at home were categorized as fatal cases. For patients who were transferred to other facilities and vital status could not be confirmed, outcome was considered unknown. The CFP was calculated by dividing the number of fatal bacteremic melioidosis cases by the total number with known outcome.

Age-specific annual incidence was calculated for 2006–2008 by dividing the number of cases by the mid-year population.13 Patients with more than one positive blood culture in the same admission or patients who were readmitted with B. pseudomallei septicemia within 20 weeks (i.e., typical duration of antibiotic therapy) after the first positive blood culture were only counted once. A Poisson distribution was assumed to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI).

The total number and CFP of bacteremic melioidosis cases were also tabulated for 2003–2005, a period before surveillance was initiated. Cases were identified through review of laboratory records. Medical charts were unavailable for cases occurring during 2003–2005, therefore outcomes were determined based only on documentation of in-hospital death in hospital databases. Patients who did not die in the hospital were counted as having non-fatal outcomes. The CFP during 2003–2005 was calculated as number of in-hospital deaths divided by total cases. The CFP in NP was compared before (2003–2005) and after (2006–2008) automated culture systems were fully operational. There were no laboratory-confirmed melioidosis cases in SK before 2005, making it impossible to assess CFP.

Data were analyzed using SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Proportions were compared using Fisher's exact test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The protocol to review medical records was approved by the institutional review board of the U.S. CDC and the Ethical Review Committee, MOPH, Thailand.

From 43,503 blood cultures collected during 2006–2008, 3,514 (8%) grew pathogens representing 3,232 patients. Burkholderia pseudomallei were confirmed in 408 (13%) patients. Among 361 (88%) case-patients who had blood inoculated in both FA/PF and MB culture bottles, 239 (66%) had B. pseudomallei isolated from both bottles, 33 (9%) from the FA/PF only, and 89 (25%) from the MB only; B. pseudomallei isolation was significantly more likely from MB than from FA/PF [91% versus 75%, P < 0.01].

Burkholderia pseudomallei were identified in 5% (78/1,513) and 19% (330/1,719) of bacteremic patients in SK and NP during 2006–2008, ranking sixth and second among all pathogens isolated, respectively. Of 408 case-patients, 128 (31%) died, 231 (57%) were discharged in improved condition, and 49 (12%) had unknown outcomes. Among patients with bacteremic melioidosis and known outcomes, the overall CFP was 36% (128/359), slightly higher in SK (31/71 [44%]) than in NP (97/288 [34%]) (P = 0.1). The CFP was similar across age groups and gender.

In NP, bacteremic meloidosis cases increased from an average 43 per year during 2003–2005 to 110 cases per year from 2006 to 2008. The CFPs during 2003, 2004, and 2005 were 60%, 33%, and 37%, respectively. The overall CFP from 2003 to 2005 was significantly higher than the CFP from 2006–2008 (Table 1). Before 2006 in NP, no bacteremic melioidosis cases were confirmed based on cultures collected at hospitals outside of the provincial hospital, while during 2006–2008, 143 (43%) of 330 bacteremic cases were confirmed from cultures collected from patients at district/military hospitals.

Table 1.

Outcome of bacteremic melioidosis in Nakhon Phanom province, Thailand, 2003–2005 and 2006–2008

| Year | Total cases | Non-fatal (n %) | Fatal (n %) | Unknown (n %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–2005* | 130† | 72 (55%) | 58 (46%) | – |

| 2006–2008 | 330 | 191 (58%) | 97 (29%) (34% of cases with known outcomes)‡ | 42 (13%) |

For 2003–2005, outcome was determined based only on documented in-hospital deaths from hospital records. Data were not available to determine whether discharged patients were in a moribund state. All patients that were discharged from the hospital were considered to have survived (i.e., non-fatal cases); therefore, the proportion of fatal cases represents a minimum estimate.

Automated culture system was in place starting on November 2005, and fully operated on January 2006.

P = 0.03 [comparing case fatality proportion in 2003–2005 (46%) to that in 2006–2008 (34% among those with known outcomes)].

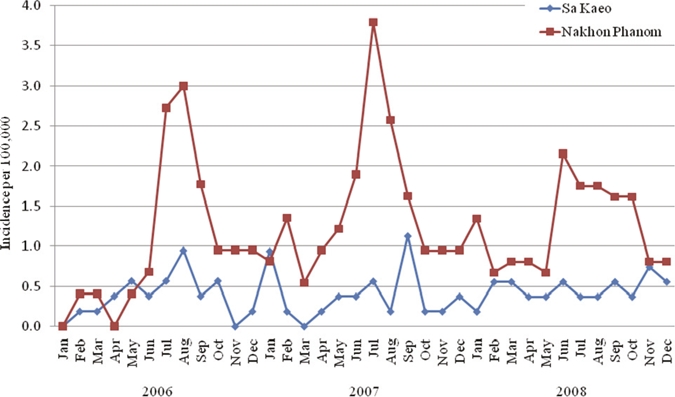

During 2006–2008, the average annual incidence of bacteremic melioidosis per 100,000 in SK was 4.9 (95% CI = 3.9–6.1), and in NP was 14.9 (95% CI = 13.3–16.6); respective PMR per 100,000 in SK was 1.9 (95% CI = 1.3–2.8), and in NP was 4.4 (95% CI = 3.6–5.3) (Table 2). Incidence was highest in older age groups in both provinces. In NP, annual peaks occurred during June–October each year, whereas in SK no clear seasonal pattern was documented (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Incidence of bacteremic melioidosis (per 100,000 persons) in Sa Kaeo and Nakhon Phanom provinces, Thailand, 2006–2008

| Sa Kaeo | Nakhon Phanom | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Cases | Deaths | Population | Incidence | 95% CI* | Cases | Deaths | Population | Incidence | 95% CI |

| 2006 | 23 | 7 | 526,432 | 4.4 | 2.8–6.6 | 90 | 26 | 734,000 | 12.3 | 9.9–15.1 |

| 2007 | 25 | 13 | 531,884 | 4.7 | 3.0–7.0 | 130 | 48 | 738,184 | 17.6 | 14.7–21.0 |

| 2008 | 30 | 11 | 537,692 | 5.6 | 3.8–8.0 | 110 | 23 | 742,500 | 14.8 | 12.2–17.9 |

| Total | 78 | 31 | 1,596,008 | 4.9 | 3.9–6.1 | 330 | 97 | 2,214,684 | 14.9 | 13.3–16.6 |

| Age | Cases | Deaths | Population | Incidence | 95% CI | Cases | Deaths | Population | Incidence | 95% CI |

| < 15 | 2 | 0 | 366,682 | 0.6 | 0.0–2.0 | 12 | 3 | 522,972 | 2.3 | 1.2–4.0 |

| 15–29 | 3 | 0 | 417,384 | 0.7 | 0.1–2.1 | 7 | 2 | 575,185 | 1.2 | 0.5–2.5 |

| 30–49 | 22 | 12 | 493,000 | 4.5 | 2.8–6.8 | 134 | 46 | 674,388 | 19.9 | 16.7–23.5 |

| 50–69 | 43 | 19 | 257,497 | 16.7 | 12.1–22.5 | 144 | 36 | 357,536 | 40.3 | 34.0–47.4 |

| ≥ 70 | 8 | 0 | 61,445 | 13 | 5.6–25.7 | 33 | 10 | 84,605 | 39 | 26.9–54.8 |

CI = confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Seasonal distribution of bacteremic melioidosis per 100,000 persons in Sa Kaeo and Nakhon Phanom, Thailand, 2006–2008.

Using active, population-based surveillance for bloodstream infections among hospitalized patients, we documented the incidence of bacteremic melioidosis in eastern and northeastern provinces of Thailand. This is the first published estimate from an area outside the highly endemic northeast. The incidence in the eastern province, SK (4.9 cases per 100,000), was higher than expected, similar to a previous estimate from northeastern Thailand,3 and much higher than reported from national passive surveillance.2 The high incidence in NP (14.9 cases per 100,000) indicates that the disease burden is likely higher than previously reported. A recent report from a neighboring province reported a similarly high incidence from 1997 to 2006 of 12.7 cases per 100,000 (21.3 per 100,000 in 2006); a strength of this study was the inclusion of non-bacteremic cases, which were not captured by our system.5 Only 50–60% of melioidosis cases are typically bacteremic,14 suggesting that the overall incidence in SK and NP are likely much higher, possibly closer to 10 and 30 cases per 100,000, respectively. The higher incidence documented here is likely due in part to the high detection of cases identified from district/military hospitals, which do not typically have access to advanced microbiology systems.

Burkholderia pseudomallei isolation was significantly improved by routine use of culture bottles optimized for fastidious organisms. Routine use of such media in melioidosis-endemic settings may improve incidence estimates and patient care.

The CFP for bacteremic melioidosis was high, especially in the eastern province where laboratory-confirmed melioidosis had not been documented before automated blood culture systems were implemented. The CFP in NP was lower during the time after automated culture systems were in place (2006–2008), even though the CFP estimate for 2003–2005 was based only on in-hospital outcome and certainly underestimated the true CFP. This decline in CFP after 2005 may have resulted partly from a surveillance artifact caused by the detection of less severe cases in the district/military hospitals, or from improvements in clinical management, as it is possible that better detection may have led to earlier diagnosis and improved treatment. Our findings underscore the importance of strengthening local microbiology capacity, especially for severe diseases like melioidosis.

Limitations of this analysis include the inability to determine final outcomes for some patients, which may have biased the results. If all patients with unknown outcomes in 2006–2008 had died, the overall CFP for those years would have been 43% (49% in SK, 42% in NP), which would be more consistent with previous reports.4 Additionally, information on the timing and selection of antibiotic therapy was not available to assess changes in clinical practice in relation to improved case detection.

Our findings demonstrate the value of active, laboratory-based surveillance to document melioidosis burden in Thailand, especially outside known endemic areas. Recognizing that our surveillance system only captured bacteremic cases, it is fair to conclude that melioidosis burden is substantially higher than previously reported.5 Additional work is required to better understand trends in CFP over time and to assess whether improved diagnostic capacity through automated systems had an impact on case management and outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the contributions of the many study collaborators, the Sa Kaeo and Nakhon Phanom provincial health offices, surveillance officers, and the district and provincial hospitals in Sa Kaeo and Nakhon Phanom.

Disclaimer: Findings presented in this paper represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Disclosure: These data were presented as an oral presentation at the 57th American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA. Scientific Session No. 75, Bacteriology III, Presentation No. 418.

Authors' addresses: Saithip Bhengsri, Henry C. Baggett, Possawat Jorakate, Anek Kaewpan, Prabda Prapasiri, Sathapana Naorat, Somsak Thamthitiwat, Prasert Salika, Leonard F. Peruski, and Susan A. Maloney, International Emerging Infections Program, Thailand MOPH-US CDC Collaboration, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand, E-mails: SaithipB@th.cdc.gov, KipB@th.cdc.gov, PossawatJ@th.cdc.gov, AnekK@th.cdc.gov, PrabdaP@th.cdc.gov, SathapanaN@th.cdc.gov, SomsakT@th.cdc.gov, PrasertS@th.cdc.gov, LeonardP@th.cdc.gov, and SusanM@th.cdc.gov. Kittisak Tanwisaid, Nakhon Phanom Hospital, Nakhon Phanom, Thailand, E-mail: Kittisak97@gmail.com. Somrak Chantra, Sa Kaeo Crown Prince Hospital, Sa Kaeo, Thailand, E-mail: SomrakC@hotmail.com. Surang Dejsirilert, National Institute of Health, Department of Medical Science, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand, E-mail: Surang_dej@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Dance DA. Melioidosis: the tip of the iceberg? Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:52–60. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bureau of Epidemiology, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand Annual Epidemiology Surveillance Report. 2009. http://203.157.15.4/surdata/disease.php?dcontent=old&ds=72 Available at. Accessed September 1, 2010.

- 3.Suputtamongkol Y, Hall AJ, Dance DA, Chaowagul W, Rajchanuvong A, Smith MD, White NJ. The epidemiology of melioidosis in Ubon Ratchatani, northeast Thailand. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:1082–1090. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.5.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanwisaid K, Surin U. Monthly rainfall and severity of melioidosis in Nakhon Phanom, northeastern Thailand. J Health Sci. 2008;17:363–375. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Limmathurotsakul D, Wongratanacheewin S, Teerawattanasook N, Wongsuvan G, Chaisuksant S, Chetchotisakd P, Chaowagul W, Day NP, Peacock SJ. Increasing incidence of human melioidosis in northeast Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:1113–1117. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaowagul W, White NJ, Dance DA, Wattanagoon Y, Naigowit P, Davis TM, Looareesuwan S, Pitakwatchara N. Melioidosis: a major cause of community-acquired septicemia in northeastern Thailand. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:890–899. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Currie BJ, Ward L, Cheng AC. The epidemiology and clinical spectrum of melioidosis: 540 cases from the 20 year Darwin prospective study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sookpranee M, Boonma P, Susaengrat W, Bhuripanyo K, Punyagupta S. Multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing ceftazidime plus co-trimoxazole with chloramphenicol plus doxycycline and co-trimoxazole for treatment of severe melioidosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:158–162. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.1.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen SJ, Thamthitiwat S, Chantra S, Chittaganpitch M, Fry AM, Simmerman JM, Baggett HC, Peret TC, Erdman D, Benson R, Talkington D, Thacker L, Tondella ML, Winchell J, Fields B, Nicholson WL, Maloney S, Peruski LF, Ungchusak K, Sawanpanyalert P, Dowell SF. Incidence of respiratory pathogens in persons hospitalized with pneumonia in two provinces in Thailand. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1811–1822. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810000646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaiwarith R, Patiwetwitoon P, Supparatpinyo K, Sirisanthana T. Melioidosis at Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital, Thailand. J Infect Dis Antimicrob Agents. 2005;22:45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waiwarawooth J, Jutiworakul K, Joraka W. Epidemiology and clinical outcome of melioidosis at Chonburi Hospital, Thailand. J Infect Dis Antimicrob Agents. 2007;25:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baggett HC, Peruski LF, Olsen SJ, Thamthitiwat S, Rhodes J, Dejsirilert S, Wongjindanon W, Dowell SF, Fischer JE, Areerat P, Sornkij D, Jorakate P, Kaewpan A, Prapasiri P, Naorat S, Sangsuk L, Eampokalap B, Moore MR, Carvalho G, Beall B, Ungchusak K, Maloney SA. Incidence of pneumococcal bacteremia requiring hospitalization in rural Thailand. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48((Suppl 2)):S65–S74. doi: 10.1086/596484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board Population Projection for Thailand, 2000–2030. 2007. http://www.nesdb.go.th/temp_social/pop.zip Available at. Accessed September 1, 2010.

- 14.Cheng AC, Currie BJ. Melioidosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:383–416. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.383-416.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]