Abstract

Bacterial killing and the development of reduced vancomycin susceptibility during continuous-infusion vancomycin (CIV) therapy were dependent on the area under the concentration-time curve over 24 h divided by the MIC (ƒAUC24/MIC), with values of ≥240 (equivalent total serum AUC24/MICs of ≥480) being bactericidal and suppressing emerging resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Also, vancomycin therapy was less likely to be bactericidal and 4.4 times more likely to lead to reduced vancomycin susceptibility in health care-associated MRSA than in community-associated MRSA.

TEXT

Infections associated with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) with higher vancomycin MICs (e.g., >1 mg/liter) have been linked to poor clinical outcomes (9, 16, 28). Furthermore, exposure to low vancomycin concentrations for prolonged durations has been associated with increasing or selecting higher MICs, especially when the bacterial burden is large or a foreign device is involved (11, 13). Concerns that traditional vancomycin dosing may be inadequate for treating MRSA infections have led to notable changes in practice. In 2006, the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) lowered the vancomycin susceptibility breakpoint from 4 to 2 mg/liter (29). Furthermore, a 2009 consensus review of vancomycin therapeutic monitoring by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists recommended more aggressive dosing to achieve serum troughs of ≥10 or 15 to 20 mg/liter for serious and complicated infections (22). These levels were proposed as practical surrogates for vancomycin AUC24/MICs (area under the concentration-time curve over 24 h divided by the MIC) of ≥400, which is the significant pharmacodynamic threshold based on available clinical evidence (14). The consensus review also cautioned that “therapeutic” AUC24/MICs would most likely be achieved with the “recommended” troughs when pathogen MICs are ≤1 mg/liter.

New approaches to vancomycin dosing in the clinical setting are required to achieve the higher targets. In response, the administration of vancomycin by continuous infusion has been proposed. Although limited study to date has not shown significant differences in clinical outcome compared with standard intermittent vancomycin dosing (3, 33), advantages in more effectively achieving and maintaining target concentrations in populations such as the critically ill have been demonstrated (17, 18). Our goal was to study continuous-infusion vancomycin (CIV) against both health care-associated (HCA) and community-associated (CA) MRSA strains in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Although such models have been used to study intermittent vancomycin dosing, ours is the first, to our knowledge, to investigate CIV and emerging resistance in MRSA.

Six clinical MRSA isolates collected from patients in 2008 were obtained from the CANWARD surveillance program conducted by The Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Alliance (http://www.can-r.com/index.php). Three genotypically defined HCA and CA strains were selected as detailed in Table 1. Vancomycin MICs were measured using broth microdilution according to CLSI methods in addition to the Etest (AB Biodisk, bioMérieux, Solna, Sweden). Our MIC data were consistent with observations that vancomycin MICs may vary with the method used. Several studies have shown consistently higher MICs with Etest than with broth microdilution, with one investigation reporting values which were 0.5 to 1.5 log2 dilution steps higher (23). Our study used the standard clinical test, broth microdilution, for vancomycin pharmacodynamic (AUC24/MIC) analyses and the more discriminating Etest to detect MIC changes during CIV therapy. Broth microdilution MIC breakpoints of the CSLI were used to define vancomycin-susceptible (≤2 mg/liter), -intermediate (4 to 8 mg/liter), and -resistant (≥16 mg/liter) isolates. One isolate (77900) was an hVISA (heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus) strain as determined by the Etest macromethod (32). A one-compartment dilutional in vitro dynamic model containing Mueller-Hinton broth (Becton Dickinson & Company, Sparks, MD) supplemented with calcium (25 mg/liter) and magnesium (12.5 mg/liter) and maintained at 37°C in a heated water bath was used. A bacterial suspension was injected into the infection flasks (250 ml), yielding initial inocula of ∼1 × 106 CFU/ml. A computerized pump (Masterflex; Cole-Parmer, Chicago, IL) with flexible tubing delivered sterile broth through the infection flasks to produce a vancomycin half-life of 7 h. Chemical grade vancomycin was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Canada (Oakville, ON) and prepared prior to each use according to the manufacturer's instructions. Active vancomycin concentrations representing the free (ƒ) fraction present in serum or interstitial/extracellular fluid were studied. The equivalent total serum concentration was predicted to be twice the free value based on an estimated 50% protein binding. A bolus dose was injected into the infection flasks, and a reservoir flask supplied CIV at a steady-state concentration of 2.5 mg/liter (ƒAUC24 = 60 mg/liter × h), 5 mg/liter (ƒAUC24 = 120 mg/liter × h), 10 mg/liter (ƒAUC24 = 240 mg/liter × h), or 20 mg/liter (ƒAUC24 = 480 mg/liter × h) over 48 h. Samples were collected at 0, 24, and 48 h; serially diluted in normal saline; plated on solid Mueller-Hinton agar; and incubated at 35°C for 24 h. Bacterial colony counts were performed, and MICs were determined using the Etest. An immunoassay (TDx) was used to ensure vancomycin levels within 10% of the target concentration. Experiments were conducted at least in triplicate on separate occasions and with growth controls. Data on bacterial killing at 24 h (BK24) and at 48 h (BK48) were subjected to analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc tests, and the occurrence of reduced vancomycin susceptibility during therapy was compared using Fisher's exact test (α = 0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of MRSA clinical isolates used in this study

| Parameter | Result obtained with isolate with stock no.: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 77900 | 81655 | 80424 | 77564 | 79002 | 77339 | |

| nuc (nuclease) gene | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| mecA gene | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| Genotype (PFGE)a | USA100 | USA100 | USA100 | USA400 | USA300 | USA300 |

| Panton-Valentine leukocidin | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| agr (accessory gene regulator) type | II | II | II | I | I | I |

| Source | Blood | Blood | Blood | Wound | Wound | Blood |

| Broth microdilution MIC (mg/liter) of: | ||||||

| Vancomycin (Etest MIC) | 2 (2) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (2) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.5) | 0.5 (1) |

| Ceftobiprole | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Clarithromycin | >32 | >32 | >32 | 0.25 | >32 | >32 |

| Clindamycin | >8 | >8 | >8 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 |

| Daptomycin | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Levofloxacin | >32 | >32 | >32 | 0.12 | 8 | 8 |

| Linezolid | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Moxifloxacin | >16 | >16 | 8 | ≤0.06 | 2 | 2 |

| Tigecycline | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazoleb | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 |

PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

Trimethoprim MIC.

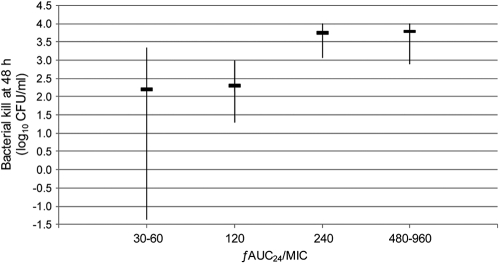

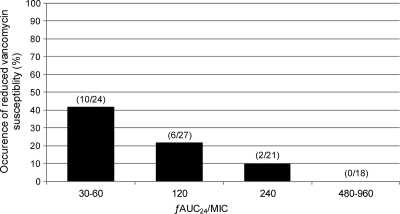

Vancomycin showed ƒAUC24/MIC-dependent activity, as detailed in Table 2 and Fig. 1. CIV producing ƒAUC24/MICs of ≤120 was bacteriostatic, with a median (interquartile range) BK48 of 2.3 (1.0 to 3.2) log10 CFU/ml, whereas CIV achieving higher ƒAUC24/MICs of ≥240 was bactericidal, with a BK48 of 3.7 (2.9 to 4.0) log10 CFU/ml (P < 0.0001). As shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2, the occurrence of reduced vancomycin susceptibility during CIV therapy was also associated with the ƒAUC24/MIC. Reduced vancomycin susceptibility characterized by increasing MICs to ≥3 mg/liter was detected in 31% (16/51) of the experiments with ƒAUC24/MICs of ≤120 and in 5% (2/39) of those with values of ≥240 (P = 0.003). Furthermore, only 11% (2/18) of the cases of reduced vancomycin susceptibility occurred with ƒAUC24/MICs of ≥240 or equivalent total serum AUC24/MICs of ≥480, and no cases were detected with ƒAUC24/MICs of ≥480.

Table 2.

Bacterial killing at 48 h and occurrence of reduced vancomycin susceptibility during CIV

| ƒAUC24/MICa | Total AUC24/MIC equivalenta,b | HCA and CA MRSA |

HCA MRSA |

CA MRSA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BK48 (log10 CFU/ml)c | RVSd at 48 h | BK48 (log10 CFU/ml) | RVS at 48 h | BK48 (log10 CFU/ml) | RVS at 48 h | ||

| 30–60 | 60–120 | 2.2 (−1.4, 3.4) | 10/24 (42) | 1.8 (−1.7, 3.9) | 10/18 (56) | 2.7 (2.1, 2.9) | 0/6 (0) |

| 120 | 240 | 2.3 (1.3, 3.0) | 6/27 (22) | 2.2 (1.4, 2.7) | 4/14 (29) | 2.7 (1.3, 4.0) | 2/13 (15) |

| 240 | 480 | 3.7 (3.1, 4.0) | 2/21 (10) | 3.7 (3.2, 4.0) | 1/10 (10) | 3.8 (2.9, 4.0) | 1/11 (9) |

| 480–960 | 960–1,920 | 3.8 (2.9, 4.0) | 0/18 (0) | 3.8 (3.1, 4.0) | 0/6 (0) | 3.8 (2.9, 4.0) | 0/12 (0) |

Based on broth microdilution MIC.

Equivalent total AUC24/MIC based on 50% protein binding in serum.

BK48 data are presented as median (interquartile range) values.

The number of isolates with reduced vancomycin susceptibility (RVS)/total (%) is shown.

Fig. 1.

Bacterial killing at 48 h stratified according to the vancomycin ƒAUC24/MIC for all isolates. Data are presented as median (interquartile range) values, and negative values indicate net bacterial growth at 48 h.

Fig. 2.

Reduced vancomycin susceptibility during therapy stratified according to the vancomycin ƒAUC24/MIC for all isolates.

As also shown in Table 2, vancomycin activity was strain dependent, with significantly less overall BK48 in HCA MRSA (2.7 [1.4 to 3.9] log10 CFU/ml) than in CA MRSA (3.2 [2.3 to 4.0] log10 CFU/ml) (P = 0.011). Most notably, reduced vancomycin activity was associated with preferential emerging resistance in HCA MRSA strains, which were involved in 83% (15/18) of the cases of reduced vancomycin susceptibility (P = 0.007). Increasing MICs during therapy were significantly more common in HCA than in CA MRSA, even when accounting for differences in the initial MICs. In our study of HCA MRSA isolates, reduced vancomycin susceptibility was often documented with the lowest ƒAUC24/MICs of 30 to 60 (56% of experiments), less frequently with ƒAUC24/MICs of 120 and 240 (29% and 10% of experiments, respectively), and not at all with ƒAUC24/MICs of ≥480. Although our study did not address the cause, the higher occurrence of reduced vancomycin susceptibility in HCA MRSA may be related to accessory gene regulator (agr) operons, which are global regulons controlling numerous critical virulence pathways in S. aureus (6). DNA sequence polymorphisms have identified four agr types, including groups I and II, which are most commonly found in HCA MRSA, and groups III and IV, which are most commonly found in CA MRSA. Some have suggested agr group II involvement in reduced vancomycin susceptibility in the hVISA and VISA phenotypes (24–26), although group I has also been identified (6). Notably, agr dysfunction or downregulation has been associated with reduced vancomycin susceptibility and increasing MICs during vancomycin exposure (21, 31). In addition, the identification of agr group II versus other genotypes in emerging resistance during therapy has raised concerns of potential agr group II-related risk for persistent infection and treatment failure (15, 27). Although only observational data, our findings of preferential increasing MICs in HCA MRSA agr group II genotypes during CIV therapy are consistent with such theories.

Other in vitro model studies have investigated vancomycin pharmacodynamics and emerging resistance in MRSA during intermittent dosing. Harigaya et al. found suppression of regrowth and resistance in MRSA when the ƒAUC24/MIC was ≥280 (4). Studies by Rose et al. and Tsuji and colleagues found that agr dysfunctional or knockout strains were associated with less vancomycin activity and increasing MICs during therapy and required higher ƒAUC24/MICs to suppress resistance than did wild-type strains (21, 31). Rose et al. were able to reduce resistance with ƒAUC24/MICs of ≥165.6, whereas Tsuji et al. required values of 112 to 169 to suppress resistance. Two subsequent in vitro dynamic studies by Rose et al. showed that hVISA strains had higher propensities to become resistant which were difficult to suppress with more aggressive vancomycin therapy alone (19, 20). Our findings were similar, with most cases of reduced vancomycin susceptibility occurring with ƒAUC24/MICs of ≤120 and few with values of ≥240.

In practical terms, our study found that CIV achieving equivalent total serum AUC24/MICs of ≤240 was bacteriostatic, with increasing MICs during therapy in almost one-third of cases. On the other hand, CIV attaining total AUC24/MICs of ≥480 was bactericidal and only occasionally associated with emerging resistance. These effective pharmacodynamic targets would be achieved with CIV at a steady-state concentration of 20 mg/liter when pathogen MICs are ≤1 mg/liter (i.e., total AUC24/MIC of ≥480). However, the pharmacodynamics of CIV at 20 mg/liter would predict significantly less activity with emerging resistance when the pathogen has a MIC of 2 mg/liter (i.e., a total AUC24/MIC of 240) and is still susceptible according to CLSI breakpoints.

The foremost clinical evidence for the AUC24/MIC target of ≥400 comes from an observational study of 63 patients with S. aureus pneumonia conducted by Moise-Broder and colleagues (14). Importantly, their study included infections associated with either methicillin-sensitive S. aureus or MRSA and therapies which frequently involved antibiotic combinations. Furthermore, unlike in vitro models which represent free antibiotic concentrations, their clinical target was based on total serum vancomycin concentrations, including the protein-bound portion. Despite these confounding factors, our significant ƒAUC24/MIC threshold of ≥240 or the equivalent total serum AUC24/MIC of ≥480 for bactericidal activity and suppression of emerging resistance in MRSA in vitro is very consistent with the clinically derived target of ≥400.

Although our findings are limited to the study of six clinical isolates, the dosing range and MIC distribution allowed relatively robust pharmacodynamic analyses of the vancomycin ƒAUC24/MIC. An important limitation of our in vitro results, however, is the lack of host immunity factors which may influence the pharmacodynamic targets in patients. Furthermore, the presence of fully active antibiotic concentrations in in vitro models also differs from the in vivo situation. We used an estimated 50% protein binding in our discussions; however, the free fraction of vancomycin in serum is quite variable, as confirmed by recent investigations (1). Our experiments were conducted over 48 h using standard initial inocula and did not examine the effects of longer durations of vancomycin exposure or larger inocula (i.e., 1 × 108 CFU/ml), which have been shown to reduce vancomycin activity and increase resistance, particularly in hVISA (2, 20, 30). Finally, our pharmacodynamic study of CIV did not consider suggestions that more aggressive vancomycin dosing may be nephrotoxic (10, 12). Notably, the clinical evidence to date is limited to retrospective or observational findings of higher doses, or more commonly higher troughs, in association with declining renal function. These data are significantly influenced and potentially obscured by the presence of confounding variables for worsening renal function such as critical illness and other nephrotoxic agents (5). Higher serum drug concentrations are as, or more, likely to be the result of declining renal function as the cause of it. Interestingly, some have suggested that CIV may reduce the incidence of adverse effects compared with intermittent vancomycin dosing (7, 8).

In conclusion, our study showed that bacterial killing and the development of reduced vancomycin susceptibility during CIV therapy were ƒAUC24/MIC dependent, with values of ≥240 (equivalent total serum AUC24/MICs of ≥480) being bactericidal and suppressing emerging resistance in MRSA. These effective pharmacodynamic targets would be achieved with CIV at a steady-state concentration of 20 mg/liter when pathogen MICs are ≤1 mg/liter (total AUC24/MIC of ≥480). Also, vancomycin therapy was less likely to be bactericidal and 4.4 times more likely to lead to reduced vancomycin susceptibility in HCA than in CA MRSA.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Berthoin K., Ampe E., Tulkens P. M., Carryn S. 2009. Correlation between free and total vancomycin serum concentrations in patients treated for Gram-positive infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34:555–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bowker K. E., Noel A. R., MacGowan A. P. 2009. Comparative antibacterial effects of daptomycin, vancomycin and teicoplanin studied in an in vitro pharmacokinetic model of infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:1044–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chua K., Howden B. P. 2009. Treating Gram-positive infections: vancomycin update and the whys, wherefores and evidence base for continuous infusion of anti-Gram-positive antibiotics. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 22:525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harigaya Y., et al. 2009. Pharmacodynamics of vancomycin at simulated epithelial lining fluid concentrations against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): implications for dosing in MRSA pneumonia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3894–3901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hazlewood K. A., Brouse S. D., Pitcher W. D., Hall R. G. 2010. Vancomycin-associated nephrotoxicity: grave concern or death by character assassination? Am. J. Med. 123:182.e1–182e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Howden B. P., Davies J. K., Johnson P. D., Stinear T. P., Grayson M. L. 2010. Reduced vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus, including vancomycin-intermediate and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate strains: resistance mechanisms, laboratory detection, and clinical implications. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23:99–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hutschala D., et al. 2009. Influence of vancomycin on renal function in critically ill patients after cardiac surgery: continuous versus intermittent infusion. Anesthesiology 111:356–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ingram P. R., Lye D. C., Fisher D. A., Goh W. P., Tam V. H. 2009. Nephrotoxicity of continuous versus intermittent infusion of vancomycin in outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34:570–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lodise T. P., et al. 2008. Relationship between vancomycin MIC and failure among patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia treated with vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3315–3320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lodise T. P., Lomaestro B., Graves J., Drusano G. L. 2008. Larger vancomycin doses (at least four grams per day) are associated with an increased incidence of nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1330–1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lodise T. P., et al. 2008. Predictors of high vancomycin MIC values among patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:1138–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lodise T. P., Patel N., Lomaestro B. M., Rodvold K. A., Drusano G. L. 2009. Relationship between initial vancomycin concentration-time profile and nephrotoxicity among hospitalized patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moise P. A., et al. 2008. Microbiological effects of prior vancomycin use in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moise-Broder P. A., Forrest A., Birmingham M. C., Schentag J. J. 2004. Pharmacodynamics of vancomycin and other antimicrobials in patients with Staphylococcus aureus lower respiratory tract infections. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 43:925–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moise-Broder P. A., et al. 2004. Accessory gene regulator group II polymorphism in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is predictive of failure of vancomycin therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1700–1705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Musta A. C., et al. 2009. Vancomycin MIC plus heteroresistance and outcome of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: trends over 11 years. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1640–1644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pea F., et al. 2009. Prospectively validated dosing nomograms for maximizing the pharmacodynamics of vancomycin administered by continuous infusion in critically ill patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1863–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roberts J. A., Lipman J., Blot S., Rello J. 2008. Better outcomes through continuous infusion of time-dependent antibiotics to critically ill patients? Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 14:390–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rose W. E., Knier R. M., Hutson P. R. 2010. Pharmacodynamic effect of clinical vancomycin exposures on cell wall thickness in heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:2149–2154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rose W. E., Leonard S. N., Rossi K. L., Kaatz G. W., Rybak M. J. 2009. Impact of inoculum size and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (hVISA) on vancomycin activity and emergence of VISA in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:805–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rose W. E., Rybak M. J., Tsuji B. T., Kaatz G. W., Sakoulas G. 2007. Correlation of vancomycin and daptomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus in reference to accessory gene regulator (agr) polymorphism and function. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59:1190–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rybak M., et al. 2009. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 66:82–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sader H. S., Rhomberg P. R., Jones R. N. 2009. Nine-hospital study comparing broth microdilution and Etest method results for vancomycin and daptomycin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3162–3165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sakoulas G., et al. 2005. Reduced susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to vancomycin and platelet microbicidal protein correlates with defective autolysis and loss of accessory gene regulator (agr) function. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2687–2692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sakoulas G., et al. 2003. Staphylococcus aureus accessory gene regulator (agr) group II: is there a relationship to the development of intermediate-level glycopeptide resistance? J. Infect. Dis. 187:929–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sakoulas G., et al. 2002. Accessory gene regulator (agr) locus in geographically diverse Staphylococcus aureus isolates with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1492–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sakoulas G., Moellering R. C., Jr., Eliopoulos G. M. 2006. Adaptation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the face of vancomycin therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42(Suppl. 1):S40–S50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Soriano A., et al. 2008. Influence of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration on the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tenover F. C., Moellering R. C., Jr. 2007. The rationale for revising the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute vancomycin minimal inhibitory concentration interpretive criteria for Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:1208–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsuji B. T., Harigaya Y., Lesse A. J., Sakoulas G., Mylotte J. M. 2009. Loss of vancomycin bactericidal activity against accessory gene regulator (agr) dysfunctional Staphylococcus aureus under conditions of high bacterial density. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 64:220–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tsuji B. T., Rybak M. J., Lau K. L., Sakoulas G. 2007. Evaluation of accessory gene regulator (agr) group and function in the proclivity towards vancomycin intermediate resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1089–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Walsh T. R., et al. 2001. Evaluation of current methods for detection of staphylococci with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2439–2444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wysocki M., et al. 1995. Comparison of continuous with discontinuous intravenous infusion of vancomycin in severe MRSA infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 35:352–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]