Abstract

We examined the links between social class, occupational self-direction, self-efficacy, and racial socialization in a sample of 128 two-parent African American couples raising adolescents. A series of multivariate, multilevel models revealed that mothers’ SES was connected to self-efficacy via its association with occupational self-direction; in turn, self-efficacy partially explained the association between occupational self-direction and racial socialization. The link between maternal self-efficacy and racial socialization depended on whether or not children had experienced discrimination. For fathers, a strong link between SES and occupational self-direction emerged, but significant associations were not found between occupational self-direction and self-efficacy, or self-efficacy and racial socialization. The discussion focuses on mother-father differences and the role of child effects in racial socialization.

Keywords: socioeconomic status, dual-earner families, African American families, parenting

Over the last two decades, a growing literature has highlighted the importance of racial and ethnic socialization processes in minority families (see recent reviews by Coard & Sellers, 2005; Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, & Stevenson, 2006). Racial socialization encompasses “specific messages and practices that are relevant to and provide information concerning the nature of race status” (Thornton, Chatters, Taylor, & Allen, 1990, p. 401). García Coll et al. (1996) argued that parenting in ethnic minority families can only be understood in reference to the larger socioeconomic and political context, including the family's position in the social stratification system. In a recent review of the literature on racial socialization, Hughes et al. noted that higher SES parents are more likely than lower SES parents to engage in two forms of racial socialization with their offspring: cultural socialization and preparation for bias. Little is known, however, about why. We sought to illuminate the processes through which social class is linked to African American mothers’ and fathers’ racial socialization with their adolescent offspring.

The hypothesized set of processes we investigated comes from the sociological and social psychological literatures on occupational socialization (Kohn, 1977; Kohn & Schooler, 1983; Parcel & Menaghan, 1994). In this conceptual framework, social class underlies adults’ access to occupations which, in turn, provide differential opportunities for value formation and psychological growth. Drawing on ideas from Kohn, Kohn and Schooler, Gecas and Seff (1989), and others, we hypothesized that socioeconomic status gives rise to differential opportunity to exercise autonomy and self-direction on the job and that occupational self-direction is an empowering experience that is linked, in turn, to an enhanced sense of self-efficacy. In the final link in our conceptual chain, we hypothesized that self-efficacy empowers African American parents to socialize their children around issues of race, specifically to teach their children about African American culture and prepare them for experiences of bias. In this paper, we used detailed interview data from 128 African American couples raising adolescents to examine this hypothesized chain of processes.

Social Structure, Self-Direction, and Self-Efficacy

A body of sociological and social psychological literature holds that occupations are an important day-to-day reflection of one's position in the social stratification system, or social class. Because people spend such a large portion of their time at work, occupations exert a strong psychological influence on employed adults (Gecas & Seff, 1989; Kohn, 1977; Kohn & Schooler, 1983). In a series of landmark studies, Kohn and his colleagues identified self-direction as a particularly important feature of occupations (Kohn & Schooler). Highly self-directed occupations provide complex, unroutinized tasks and offer opportunities to exercise autonomy, creativity, and problem-solving. In a 10-year longitudinal study of a sample of over 3,000 employed adult men, Kohn and Schooler found that occupational self-direction was associated with increased intellectual flexibility, higher values for self-direction for self and children, and greater involvement in self-directed leisure activities.

Several studies have examined the implications of occupational self-direction for parenting, although none that we know of have explored this association in regard to racial socialization specifically. In analyses of data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Parcel and Menaghan (1994) found that, holding constant the effects of education, age, race, and other characteristics that select people into occupations, mothers in highly complex occupations created more stimulating home environments for their young children. Moreover, when mothers transitioned into more complex occupations, the quality of the home environments they provided for their young children improved, whereas when mothers moved into less complex occupations, the quality of home environments declined (Menaghan & Parcel, 1995).

Occupations that come with opportunities to exercise self-direction provide ongoing feedback about competence that may facilitate the development of feelings of self-efficacy. As Bandura (1989, p. 1175) explained:

Among the mechanisms of personal agency, none is more central or pervasive than people's beliefs about their capabilities to exercise control over events that affect their lives. Self-efficacy beliefs function as an important set of proximal determinants of human motivation, affect, and action.

Using a sample of fathers of adolescents, Gecas and Seff (1989) showed that, controlling for education and occupational prestige, men who held jobs high in control and complexity reported higher levels of self-efficacy. We were interested in whether self-efficacy, in turn, was related to parents’ racial socialization.

Racial Socialization

Racial socialization is an important dimension of parenting in racial and ethnic minority families (Coard & Sellers, 2005; Hughes & Chen, 1997; Hughes et al., 2006; McHale, et al., 2006; Thornton et al., 1990). In an analysis of the National Survey of Black Americans, two thirds of the parents surveyed reported engaging in some form of racial socialization (Thornton et al.). Although researchers have identified several dimensions of racial socialization (see review by Hughes et al.), we focused on the two aspects that have received the most attention: (a) cultural socialization, defined as “parental practices that teach children about their racial or ethnic heritage and history; that promote cultural customs and traditions; and that promote children's cultural, racial, and ethnic pride, either deliberately or implicitly” (Hughes et al., p. 749); and (b) preparation for bias, defined as “parents’ efforts to promote their children's awareness of discrimination and prepare them to cope with it” (Hughes et al., p. 756).

Thornton et al. (1990) reported that the more educated parents were, the more likely they were to report engaging in racial socialization. A closer examination of the data, however, revealed that racial socialization may not have different correlates for mothers and fathers: When examined separately, education was positively correlated with mothers’ racial socialization but was not related to fathers’ racial socialization (Thornton et al.). In addition, several studies have suggested that mothers engage in significantly higher levels of racial socialization than do fathers. Note, however, that it is more common for studies to compare unrelated mothers and fathers (e.g., Thornton et al.) than to compare mothers and fathers in the same families (but see McHale et al., 2006).

In summary, we hypothesized that higher social class (assessed in terms of education, income, and occupational prestige) would be linked to higher levels of self-direction in the workplace, and that higher occupational self-direction, in turn, would be associated with higher levels of parental self-efficacy. Studying a sample of dual-earner African American families, we anticipated that parents who felt highly efficacious would engage in higher levels of racial socialization because these practices represent proactive ways to prepare children to cope effectively with life in a majority culture. We hypothesized that the same processes would be evident for mothers and fathers, but would be more pronounced for mothers given their greater role in racial socialization.

We also suspected, however, that the link between self-efficacy and racial socialization would depend on parents’ and children's race-related beliefs and experiences, leading us to examine several potential moderators. Several studies have shown that parents engage in more cultural socialization when they identify more closely with their racial or ethnic group (Hughes, 2003; Knight, Bernal, Garza, Cota, & Ocampo, 1993; Thomas & Speight, 1999). Scholars have argued that racial identity is multidimensional, making the distinction between the centrality of race or ethnicity in a person's identity and the extent to which a person holds his or her group in high or low regard (Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997). We examined both aspects of parents’ identity as moderators of the link between self efficacy and racial socialization. In addition, discrimination may alert parents that it is important to prepare their children to deal with race-related negative treatment. Indeed, Hughes and Chen (1997) found that parents engaged in more preparation for bias when they reported more interpersonal prejudice on the job, and Miller and MacIntosh (1999) reported an association between children's reports of racial socialization and their reports of discrimination. These findings suggest that self-efficacy may differentially evoke racial socialization depending on parents’ identity and parents’ and children's exposure to discrimination. Accordingly, we examined parents’ racial identity (i.e., centrality, private regard), parents’ reports of workplace discrimination, and youth's reports of discrimination as possible moderators of the effects of parents’ self-efficacy on racial socialization.

We examined the hypothesized processes in a sample of 128 African American, dual-earner couples. Having identical data from mothers and fathers in the same families enabled us to treat the couple as the unit of analysis and to make within-family comparisons of mothers versus fathers, something rarely done in the literature on African American families.

Research Questions

We asked four questions:

Does occupational self-direction mediate the effect of social class on self-efficacy?

Does parental self-efficacy mediate the association between occupational self-direction and racial socialization?

Is the link between self-efficacy and racial socialization moderated by parents’ ethnic identity or parents’ or children's experiences of discrimination?

Are the hypothesized associations similar for mothers and fathers?

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a larger study of 202 African American families involved in a longitudinal study of gender development. The goal of the larger study was to conduct an in-depth examination of family processes and family relationships of families that (a) self-identified as Black or African American, (b) had a mother-figure and a father-figure present, and (c) had a target child in the 4th through 7th grade (d) with at least one older sibling living at home.

Because of our interest in collecting extensive longitudinal data from mothers, fathers, and youth we chose a hands-on data collection strategy. This meant that we did not seek a nationally representative sample, but rather one that allowed us to achieve an in-depth look at the experiences of multiple family members. Two strategies were used to generate this sample. First, individuals who lived in the targeted urban areas were hired to recruit families from local community organizations (e.g., churches, schools, youth organizations, local businesses). The recruiters used multiple methods, including distributing flyers and holding information sessions. Approximately half of the participants were recruited in this manner. Second, a marketing list was purchased that contained households with African American students in the relevant grades in school and geographic areas of interest. Letters about the research project and participation criteria were sent to the families. Interested families responded either by returning a postcard or calling a toll-free number. Because the marketing firm could not narrow the list to two-parent families or to families in which an older sibling was present who met our criteria, letters were sent to many ineligible families, making it impossible to calculate a response rate. Of the 1,665 African American families that received a letter, 142 families responded. Of these, 93 families met our criteria and 86 ultimately participated. The final sample size was 202. The sample is not representative of African American families but provides a depth of information on multiple family members that is unique.

We limited the current analysis to dual-earner couples so that we could make within-family comparisons of employed mothers and fathers. To be included in the current analyses, both parents had to be working for pay at least ten hours a week and parents had to be either married or cohabiting. Of the 202 families in the larger sample, we eliminated 53 because one or both parents did not meet our work hours criterion, 15 because the father figure was not the mother's romantic partner (these father figures included grandfathers and uncles), and six because fathers declined to report their incomes (a component of our indicator of social class), for a total sample size of 128 dual-earner couples. In all cases, parents were raising offspring who self-identified as Black or African American, making racial socialization relevant for all families. Of the mothers, 120 self-identified as Black or African American, five as European American, and three as Hispanic. Of the fathers, 127 self-identified as Black or African American, and one as European American. Because mothers’ race and cultural socialization were correlated (see Table 1), we controlled for parent's race in the analyses.

Table 1.

Correlations between Parents’ Social Class, Occupational Self Direction, Self-Efficacy, and Racial Socialization (N = 128 Families)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Offspring gendera | – | .08 | -.04 | .09 | .009 | .09 | -.0005 | .06 | .14 | .17† | .08 | .06 | .08 |

| 2. Offspring age | .08 | – | -.006 | .006 | .009 | -.03 | -.07 | -.02 | .02 | .20* | -.10 | .02 | .09 |

| 3. Offspring relatednessb | .01 | -.02 | – | -.04 | -.19* | -.19* | -.20* | -.04 | .004 | -.02 | -.13* | -.19* | .04 |

| 4. Parent racec | .01 | .09 | -.08 | – | .01 | -.07 | -.07 | .10 | .07 | .05 | .04 | .08 | -.09 |

| 5. Parent social class | .09 | -.05 | -.003 | -.05 | – | .52*** | .22* | .21* | .02 | -.17† | .17† | .05 | -.007 |

| 6. Parent self direction | -.10 | .07 | .02 | .11 | .28** | – | .16† | .04 | -.03 | .02 | .04 | .03 | -.14 |

| 7. Parent self-efficacy | -.14 | -.10 | .01 | .007 | .17† | .32*** | – | .12 | -.03 | -.10 | .22* | .30*** | -.16† |

| 8. Parent cultural socialization | -.06 | .02 | -.04 | -.17* | .23** | .19* | .26** | – | .52*** | -.002 | .37*** | .27** | .05 |

| 9. Parent bias preparation | -.04 | .01 | -.06 | -.10 | .24** | .21* | .29** | .52*** | – | .03 | .27** | .08 | .16† |

| 10. Offspring discrimination | .17† | .20* | -.03 | -.07 | .07 | -.05 | .04 | .14* | .08 | – | .07 | .06 | -.04 |

| 11. Parent centrality | -.02 | -.14 | -.03 | .13 | .34*** | .12 | .23** | .40*** | .24** | .20* | – | .41*** | -.04 |

| 12. Parent regard | .03 | -.13 | -.14* | .04 | .24** | -.08 | .06 | .20* | .10 | .20 | .31*** | – | .05 |

| 13. Parent workplace discrimination | -.13 | -.008 | .11† | -.14* | .07 | -.09 | -.02 | .21† | .15† | .04 | .13 | .11 | – |

Note. Correlations below the diagonal are for mothers; correlations above the diagonal are for fathers.

Offspring gender: 0 = female, 1 = male.

Biological relatedness to parent: 0 = biologically related, 1 = not biologically related.

Parent race: 0 = Black/African American, 1 = other.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Our analyses focused only on the older siblings for two reasons. First, our research questions highlighted mother-father comparisons. This emphasis required a multivariate multilevel modeling (MLM) approach which precluded including both siblings. Second, we chose older rather than younger siblings because, using the larger sample from this project, McHale et al. (2006) reported that parents engaged in more racial socialization with older offspring. We reasoned that focusing on older youth would maximize our chances of identifying meaningful correlates of racial socialization. Older offspring ranged in age from 10 to 19 years (M = 14.29 yrs, SD = 2.01). Ninety-two percent were the biological offspring of the mother; 80% were the biological offspring of the father. Because biological relatedness was associated with fathers’ social class, self-direction, and self-efficacy (see Table 1), it was controlled in the analyses.

Procedure

Participating families were interviewed in their homes during two to three-hour visits. When the two interviewers arrived, informed consent was obtained from each family member. The interviewers (most of whom were African American) then divided up, with one focusing on the parents and the other on the offspring. The parents’ interviews consisted of a section they completed together followed by individual interviews. Interviews focused on personal characteristics, work, family relationships, parenting, and psychological adjustment. Offspring were interviewed sequentially about most of the same topics. Families received a $200 honorarium.

Measures

Social class was measured at the level of the individual parent rather than the family (see Perry-Jenkins & Folk, 1994, for an example of this approach). Specifically, we standardized and summed three indicators of social class: (a) parent's report of gross annual income from wages, (b) number of completed years of schooling, and (c) occupational prestige (coded from job titles using the National Opinion Research Center's coding system; Nakao & Treas, 1994). Table 2 includes means, standard deviations, ranges, and t tests of mother-father differences for all study variables. As can be seen in Table 2, fathers earned more income than mothers did, although mothers were better educated than fathers were. Fathers and mothers did not differ on occupational prestige. Cronbach's α for the three-item social class index was .66 for mothers and .79 for fathers.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, Ranges, and Tests of Mother-Father Differences for Study Variables (N = 128 mother-father dyads)

| Variables | Subscale | Mothers (M) | Fathers (F) | T-test M and F t (df) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | |||

| Social class | Income | $40,452 | $21,763 | $2,700 - $140,000 | $58,038 | $47,128 | $1,200 - $425,000 | -4.01*** (125) |

| Educationa | 15.01 | 1.75 | 10 - 19 | 14.58 | 2.12 | 9 - 19 | 2.35* (127) | |

| Occupational prestige | 49.53 | 11.39 | 24.3 – 74.77 | 49.16 | 13.41 | 22.95 – 74.77 | .23 (126) | |

| Occupational Self-Direction | 39.44 | 9.58 | 17 - 63 | 40.70 | 12.00 | 19 - 64 | -.98 (126) | |

| Self-Efficacy | 53.83 | 6.01 | 32 – 66 | 54.05 | 6.50 | 37 - 70 | -.31 (127) | |

| Racial Socialization | Cultural socialization | 21.73 | 5.35 | 5 - 30 | 17.51 | 6.43 | 6 - 30 | 7.05*** (127) |

| Prep for bias | 29.41 | 6.18 | 12 - 42 | 26.47 | 8.16 | 9 - 42 | 3.80*** (126) | |

| Workplace discrimination | 2.02 | .89 | 1 - 4 | 1.96 | .91 | 1 - 4 | .65 (123) | |

| Ethnic Identity | Racial centrality | 2.73 | .55 | 1.13 - 4 | 2.72 | .56 | 1.25 - 3.88 | -.01 (117) |

| Private regard | 3.74 | .25 | 3.14 - 4 | 3.64 | .37 | 2.43 - 4 | 2.76** (116) | |

12 represents a high school education.

† p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

To assess occupational self-direction, we used a shortened version of Lennon's (1994) Work Dimensions scale. Sixteen items were rated from 1 (very much) to 4 (not at all). A sample (reverse-coded) item is: “You follow the same routine day-in and day-out” with higher scores indicating more self direction (α = .86 for mothers; .91 for fathers). Fathers and mothers did not differ in their reports of occupational self-direction.

Self-Efficacy was assessed with a subscale of Paulhus's (1983) measure of Spheres of Control. Ten items (e.g., “When I get what I want, it's usually because I worked hard for it”) were rated on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy. Paulhus reported a Cronbach's α for this subscale of .75. Cronbach's α for mothers and fathers in our sample was .52 and .53, respectively, suggesting that this scale may have less internal consistency for African-American parents compared to other populations. Psychometric analyses were conducted to try to improve the internal consistency of this measure, but no approach resulted in a set of items with better internal reliability that could be used for both parents. Fathers and mothers did not differ on self-efficacy.

Racial socialization was assessed using two scales developed by Hughes and Chen (1997) that were completed separately by mothers and fathers: cultural socialization (5 items; e.g., “I've read or provided Black history books to my child”) and preparation for bias (7 items; e.g., “I've talked to my child about racism”). Higher scores indicated a higher frequency of racial socialization practices. Cronbach's α was consistently above .82. Mothers engaged in higher levels of cultural socialization and preparation for bias than did fathers.

We examined four possible moderators of the links between self-efficacy and racial socialization. We assessed offspring's reports of personal experiences with discrimination using a measure designed for this study but based on Hughes and Dodge's (1997) racism in the workplace scale. The measure contained 16 items (e.g., “How often have kids at school called you names because you are Black/African American/part Black/African American?”) that were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). Because the measure lacked sufficient variability to use as a continuous variable, we recoded it such that 0 referred to no experiences with discrimination and 1 referred to any experiences with discrimination. We examined parents’ workplace discrimination with a measure developed by Hughes and Dodge (1997) that contained 4 items (e.g., “In my place of work, African Americans get the least desirable assignments”) that were rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). High numbers indicated high levels of reported workplace discrimination (α = .87 and .86 for mothers and fathers, respectively). Mothers and fathers did not differ on reports of workplace discrimination. We assessed parents’ racial centrality and private regard with subscales from the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (Sellers et al., 1997). Racial centrality was measured with 8 items (e.g., “In general, being Black/African American is an important part of my self-image”), and private regard with 7 items (e.g., “I am happy that I am Black/African American”). Items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree) and were scored such that high numbers referred to high levels of racial centrality and private regard (α = .73 and .74 for mothers’ and fathers’ racial centrality, respectively; α = .74 and .60 for mothers’ and fathers’ private regard for race, respectively). Mothers and fathers did not differ on centrality, although mothers held being African American/Black in higher regard than fathers did. Non-African American parents did not complete the measures of centrality or private regard because it would not have made sense to do so. All parents completed the workplace discrimination measure because those items were about the workplace, not the person. Thus, sample sizes in the moderator analyses varied slightly.

Results

Descriptive Results

As can be seen in Table 1, parents who engaged in higher levels of cultural socialization also engaged in more preparation for bias. For mothers, significant associations were found between most of the variables of substantive interest. For example, mothers’ social class was positively associated with their occupational self-direction, self-efficacy, and both indicators of racial socialization. Significant correlations were sparser for fathers. For example, fathers’ social class was significantly related to occupational self-direction and to cultural socialization but not to self-efficacy or preparation for bias. Consistent with previous literature, most of the hypothesized moderators were positively related to racial socialization for both parents.

Multilevel Model Analysis Plan

We examined the connections between parents’ social class, occupational self-direction, self-efficacy, and racial socialization using multivariate MLM, a statistical approach that extends regression analysis to nested data (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). In our analyses, mothers and fathers were nested within families. The multivariate approach enabled us to statistically compare the strength of the key associations of interest for mothers versus fathers at each step. Although the dependent variable changed with each step in the analysis, the basic organization of the models was always the same. At level 1, the individual parent level, we included two control variables (i.e., parent's race and biological relatedness to the child) as well as the parent-specific variables of substantive interest (i.e., parent's gender, social class, occupational self-direction, and self-efficacy). At level 2, the family level, we included factors that were shared by the two parents, specifically the gender and age of the child, which we treated as controls.

The first MLM analysis predicted parents’ occupational self-direction with their social class, holding constant the set of control variables that were used in every analysis, specifically the child's age, gender (0 = female; 1 = male), and biological relatedness to parent (0 = biologically related; 1 = not biologically related), as well as the parent's race (0 = Black or African American; 1 = Other). In the second analysis, we entered the controls, social class, and occupational self-direction to predict self-efficacy, and in the third set of analyses, we entered the controls, social class, occupational self-direction, and self-efficacy to predict the two dimensions of racial socialization. To examine indirect effects, we used Sobel tests (Sobel, 1982). Specifically, we were interested in whether social class was related to self-efficacy via its association with occupational self-direction and whether occupational self-direction was related to cultural socialization and preparation for bias via its effect on self-efficacy. We conducted the Sobel tests (separately for mothers and fathers) only when the initial criteria for mediation were met (see Baron & Kenny, 1986).

The tests of moderating effects followed the same logic outlined above and included the same control and independent variables. Following Aiken and West (1991), in these analyses we centered all variables. Then we added each moderator as a main effect and created an interaction term combining the moderator and the independent variable (IV) of interest. Each moderator was examined in a separate set of analyses, because they were intercorrelated.

To compare mothers and fathers, we conducted each set of analyses described above in two ways. First, we included separate terms for the IV for mothers and fathers to determine the association between the IV and the dependent variable (DV) for each parent. Second, we interacted the IV of interest (e.g., in the first analysis, the IV of interest was social class) with the gender of the parent to determine whether the strength of the association between the IV and DV differed significantly for mothers versus fathers. We only reported the findings from the second set of tests when the associations for mothers and fathers were significantly different; otherwise, it can be assumed that no significant mother-father differences emerged.

Links between Social Class and Occupational Self-Direction

The first analysis examined the connection between social class and occupational self-direction. As can be seen in the first column of Table 3, social class was positively associated with occupational self-direction for both mothers and fathers: Parents with higher socioeconomic status experienced more self-direction on the job. The test of parent differences revealed that the association was significantly stronger for fathers than mothers (γ = 1.23, SE =.53, t = 2.33, p < .05).

Table 3.

Results of Multivariate Multilevel Analysis Depicting the Paths Linking Parents’ Social Class, Occupational Self-Direction, and Self-Efficacy (N = 255 Observations from 128 Families)

| Occupational Self-Direction | Self-Efficacy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | SE | t Ratio | γ | SE | t Ratio | |

| Intercept for mothers | 1.74 | 3.68 | .47 | -2.98 | 2.26 | -1.32 |

| Intercept for fathers | 2.17 | 3.75 | .58 | -2.86 | 2.30 | -1.24 |

| Offspring gendera | .46 | 1.18 | .39 | .79 | .83 | .96 |

| Offspring age | .12 | .29 | .41 | -.27 | .21 | -1.31 |

| Offspring relatednessb | 1.38 | 1.85 | .75 | 1.70 | 1.15 | 1.48 |

| Parent racec | -3.17 | 3.21 | -.99 | 1.14 | 1.97 | .58 |

| Mother social class | 1.24*** | .36 | 3.42 | .19 | .23 | .82 |

| Father social class | 2.48*** | .37 | 6.61 | .49 | .26 | 1.85 |

| Mother self direction | .19*** | .06 | 3.52 | |||

| Father self direction | .02 | .05 | .41 | |||

Offspring gender: 0 = female, 1 = male.

Biological relatedness to parent: 0 = biologically related, 1 = not biologically related.

Parent race: 0 = Black/African American, 1 = other.

*p < .05.

**p < .01.

p < .001.

Links between Occupational Self-Direction and Self-Efficacy

The second analysis built on the first, this time testing whether self-direction predicted parents’ feelings of self-efficacy. As can be seen in the second column of Table 3, there was a strong positive association between occupational self-direction and self-efficacy for mothers but not for fathers. The strength of the association between occupational self-direction and self-efficacy differed significantly for the two parents (γ = -.17, SE =.08, t = -2.20, p < .05). Given the lack of association for fathers, we conducted the Sobel test only on the associations for mothers. As predicted, mothers’ opportunities to exercise self-direction on the job mediated the association between their social class and self-efficacy, z = 2.34, p < .05. For fathers, in contrast, social class was related to greater occupational self-direction, but opportunities to exercise self-direction were not linked to self-efficacy.

Links between Self-Efficacy and Racial Socialization

The third set of models examined the links between parents’ self-efficacy and their engagement in cultural socialization and preparation for bias. As can be seen in the first column of Table 4, mothers’ self-efficacy was positively associated with how much they engaged in cultural socialization practices with their children. The association for fathers was in the same direction but was not significant. Given the lack of association for fathers, we conducted the Sobel test only on the associations for mothers. As predicted, mothers’ self-efficacy mediated the link between their occupational self-direction and cultural socialization, z = 1.97, p < .05. Note also that, for both mothers and fathers, socioeconomic status was a significant predictor of cultural socialization even with self-direction and self-efficacy in the model; the higher their social status, the more mothers and fathers engaged in cultural socialization practices.

Table 4.

Results from Multilevel Model Analyses Predicting Cultural Socialization and Preparation for Bias from Social Class, Occupational Self-Direction, and Self-Efficacy (N = 255 Observations from 128 Families)

| Cultural Socialization | Preparation for Bias | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | SE | t Ratio | γ | SE | t Ratio | |

| Intercept for mothers | 21.10*** | 1.99 | 10.62 | 28.77*** | 2.39 | 12.04 |

| Intercept for fathers | 16.880*** | 2.03 | 8.28 | 25.71*** | 2.46 | 10.47 |

| Offspring gendera | -.05 | .84 | -.06 | -.59 | .10 | -.60 |

| Offspring age | .05 | .21 | .26 | .11 | .25 | .43 |

| Offspring relatednessb | -.33 | 1.07 | -.31 | -.53 | 1.34 | -.39 |

| Parent racec | 1.01 | 1.68 | .60 | 1.50 | 1.99 | .76 |

| Mother social class | .43* | .20 | 2.14 | .43 | .23 | 1.82 |

| Father social class | .73** | .25 | 2.91 | .30 | .33 | .90 |

| Mother self direction | .06 | .05 | 1.23 | .07 | .06 | 1.16 |

| Father self direction | -.09 | .05 | -1.67 | -.06 | .07 | -.90 |

| Mother self-efficacy | .17* | .08 | 2.22 | .28** | .09 | 3.12 |

| Father self-efficacy | .13 | .08 | 1.55 | -.03 | .11 | -.29 |

Offspring gender: 0 = female, 1 = male.

Biological relatedness to parent: 0 = biologically related, 1 = not biologically related..

Parent race: 0 = Black/African American, 1 = other.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

A similar pattern of results held for preparation for bias. As can be seen in the second column of Table 4, the link between self-efficacy and preparation for bias was significant for mothers but not for fathers. Moreover, there was a significant mother-father difference (γ = -.31, SE =.14, t = -2.26, p < .05). As was the case for cultural socialization, self-efficacy mediated the association between mothers’ occupational self-direction and their preparation for bias, z = 2.36, p < .05.

Before moving to the moderator analyses, we conducted one set of post hoc analyses. One possible reason why fathers’ data did not conform to our hypotheses is that fathers’ racial socialization may be orchestrated by mothers, who are generally more involved in racial socialization than fathers (McHale et al, 2006; Thornton et al., 1990). We ran new analyses predicting fathers’ racial socialization with mothers’ social class, occupational self-direction, and self-efficacy, but found no evidence for this post hoc explanation.

Do Experiences with Discrimination and Attitudes about Race Moderate the Links between Self-Efficacy and Racial Socialization?

In our final analyses, we were interested in whether the effects of self-efficacy on racial socialization depended on children's and parents’ exposure to discrimination and parents’ racial identities. We examined four moderators: offspring's exposure to discrimination, parents’ reports of discrimination at work, the centrality of race in parents’ identity, and parents’ private regard for being Black/African American. We examined each moderator in separate multivariate MLM models, following the logic described above and including all of the other predictors included in Table 4. As before, we performed these analyses in two steps, with the first step examining the interactions of interest for mothers and fathers and the second step testing for mother-father differences in the strength of the interactions. With one important exception, these analyses did not produce evidence of moderated effects, although several moderators emerged as significant main effect predictors of racial socialization, indicative of additive effects.

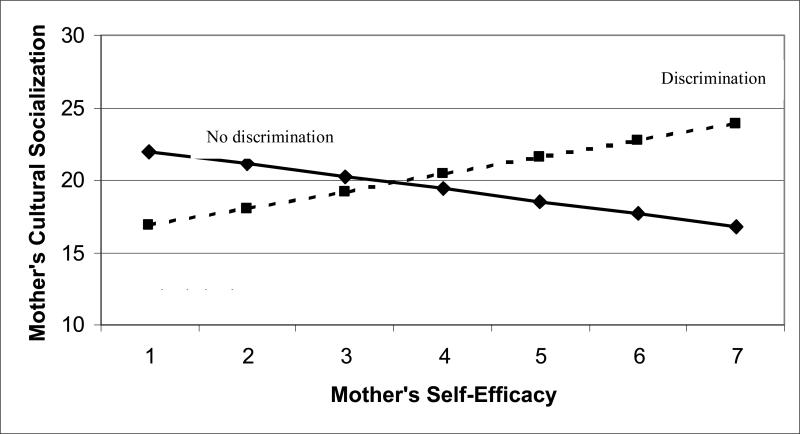

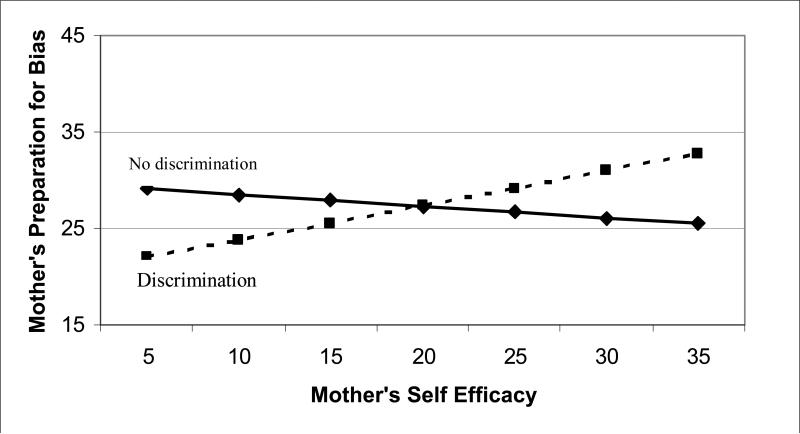

Children's experiences of discrimination

The only significant moderator of the link between self-efficacy and racial socialization was children's reports of discrimination. For cultural socialization, we found a significant self-efficacy X children's report of discrimination interaction for mothers (γ = -.41, SE =.18, t = -2.25, p < .05). As can be seen in Figure 1, when offspring had experienced discrimination, mothers’ cultural socialization increased with greater self-efficacy (γ = .23, SE =.08, t = 2.88, p < .01). In contrast, when offspring reported no experiences of discrimination, the association between maternal self efficacy and cultural socialization was not significant (γ = -.17, SE =.16, t = -1.04, ns). This interaction was not significant for fathers (γ = -.07, SE = 0.18, t = -0.37, ns). Similarly, for preparation for bias, the self efficacy X children's reports of discrimination interaction was significant for mothers (γ = -.48, SE =.21, t = -2.27, p < .05). When offspring had experienced discrimination, more efficacious mothers engaged in more preparation for bias (γ = .36, SE =.10, t = 3.76, p < .001). When children had not experienced discrimination, however, the association between self efficacy and preparation for bias was not significant (γ = -.12, SE =.19, t = -.62, ns; see Figure 2). This interaction was not significant for fathers (γ = -.31, SE =.24, t = -1.32, ns).

Figure 1.

Cultural Socialization as a Function of Mother's Self-Efficacy and Offspring's Experience of Discrimination.

Figure 2.

Preparation for Bias as a Function of Mother's Self-Efficacy and Offspring's Experience of Discrimination.

Workplace discrimination

We found no evidence that the extent to which parents reported discrimination at work moderated the association of self-efficacy and cultural socialization, but a main effect emerged for mothers: Mothers who reported more discrimination engaged in more cultural socialization (γ = 1.15, SE =.49, t = 2.36, p < .05). This association was not significant for fathers (γ = 0.25, SE =.60, t = 0.41, ns). Similarly, for preparation for bias, the self-efficacy X workplace discrimination interaction was not significant for either parent, but workplace discrimination emerged as a significant main effect for mothers (γ = 1.19, SE = .57, t = 2.08, p < .05) and as a nonsignificant trend for fathers (γ = 1.31, SE =.78, t = 1.68, p < .10): The more discrimination parents reported, the more they engaged in preparation for bias with their offspring.

Racial centrality

The hypothesized interactions involving racial centrality were not significant for either parent. We did find additive effects, however: Mothers (γ = 2.89, SE =.82, t = 3.54, p < .001) and fathers (γ = 3.15, SE =.96, t = 3.28, p < .01) engaged in more cultural socialization when race was more central in their identities. In the analyses focused on preparation for bias, racial centrality emerged as a significant main effect for fathers (γ = 3.90, SE = 1.25, t = 3.12, p < .01) and as a nonsignificant trend for mothers (γ = 1.70, SE =.99, t = 1.72, p < .10): Parents engaged in more preparation for bias with their offspring when race played a more central role in their identity.

Private regard

We found no evidence that parents’ private regard for race moderated the association between self-efficacy and cultural socialization. For fathers, high private regard was related to higher levels of cultural socialization (γ = 3.63, SE = 1.47, t = 2.47, p < .05), but this association was not significant for mothers (γ = 2.49, SE = 1.83, t = 1.36, ns). Private regard for race was not a significant correlate of preparation for bias for either parent.

Summary

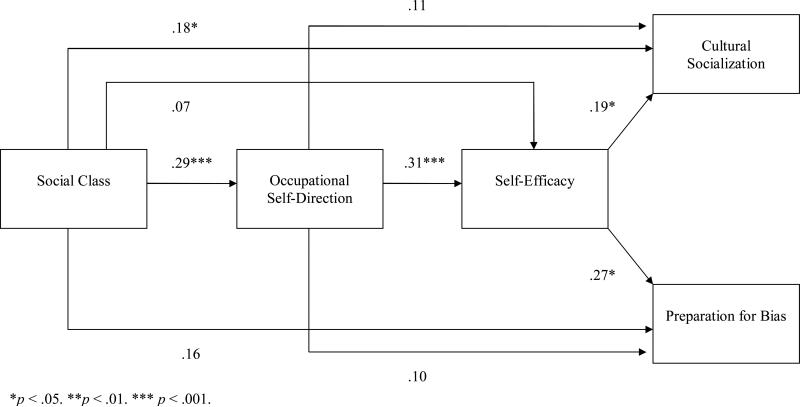

To summarize, as can be seen in Figure 3, our findings revealed a set of indirect associations for mothers such that higher social class was associated with more occupational self-direction, which, in turn, was linked to higher levels of self-efficacy. As predicted, mothers’ self-efficacy was associated with higher levels of cultural socialization and preparation for bias. For cultural socialization, there was also a direct path between mothers’ social class and racial socialization, indicating that occupational self-direction and self-efficacy are not the entire explanation for the social class-cultural socialization link. Additionally, the link between self-efficacy and racial socialization was evident for mothers whose offspring had experienced discrimination, but not for mothers whose children had not encountered discrimination.

Figure 3.

Path Analysis coefficients from a Series of MLM Analyses Linking Mother's Social Class, Occupational Self-Direction, Self-Efficacy, and Racial Socialization.

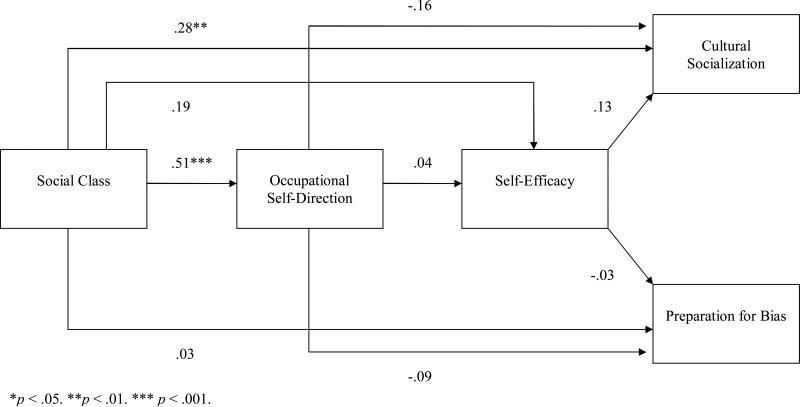

The hypothesized set of linkages did not hold for fathers, however. As can be seen in Figure 4, although higher social class was strongly linked to higher levels of occupational self-direction for fathers, self-direction was not related to paternal self-efficacy, and self-efficacy, in turn, was not linked to fathers’ racial socialization.

Figure 4.

Path Analysis coefficients from a Series of MLM Analyses Linking Father's Social Class, Occupational Self-Direction, Self-Efficacy, and Racial Socialization.

With the exception of children's reports of discrimination, the hypothesized moderators generally emerged as significant main effects, replicating previous findings about the correlates of racial socialization but not illuminating specific conditions under which parents’ self-efficacy is more or less associated with racial socialization.

Discussion

García Coll and colleagues (1996) argued that studies of ethnic minority families need to contextualize parenting and other family processes in the broader socioeconomic and political contexts within which these families are embedded. In this study, we examined the link between social class and racial socialization in a sample of 128 African American employed mother-father dyads, grounding our ideas in occupational socialization theory (e.g., Kohn & Schooler, 1983; Parcel & Menaghan, 1994). In our concluding remarks, we address four issues: (a) mother-father differences in the patterns of association, (b) the role of child effects in racial socialization, (c) strengths and limitations of our study, and (d) implications for the field.

Links between Social Class and Racial Socialization for Mothers versus Fathers

For mothers, our findings extended the literature on social class and occupational socialization (e.g., Gecas & Seff, 1989; Kohn, 1977; Kohn & Schooler, 1983) to racial socialization. Multilevel analyses revealed the hypothesized linkages between mothers’ socioeconomic status, occupational self-direction, feelings of self-efficacy, and reports of their engagement in two forms of racial socialization—cultural socialization and preparation for bias. Specifically, we found that self-direction mediated the path from social class to self-efficacy and that self-efficacy, in turn, mediated the path from self-direction to cultural socialization and preparation for bias. Limited by cross-sectional data and a non-experimental design, we cannot make claims about causation, but the pattern of results is consistent with the idea that self-directed work may empower African American mothers in ways that activate parenting practices around race. This finding points to the importance of examining occupational self-direction as a correlate of psychological functioning in employed adults in future research.

For fathers’ cultural socialization, social class was a positive correlate—fathers of higher socioeconomic status reported engaging in more cultural socialization practices around race—but the model broke down when we found no link between fathers’ occupational self-direction and their self-efficacy. Moreover, there was no link between self-efficacy and fathers’ racial socialization practices. Why might this be the case? Mothers engaged in higher levels of racial socialization overall compared to fathers, a finding consistent with previous studies (e.g., Thornton, et al., 1990). Thus, there was more racial socialization behavior to explain for mothers than for fathers. Note, however, that, mothers and fathers did not differ in terms of mean levels of occupational self-direction or self-efficacy: Despite similar levels of self-efficacy, occupational self-direction mattered for mothers’ self-efficacy but not for fathers’. Parents also did not differ on mean reports of workplace discrimination, so the idea that men might have experienced more discrimination on the job, with attendant erosion of self-efficacy, was not supported. African American fathers in our sample may have been subjected to discrimination in other domains of life, such as educational settings or previous jobs, or been targeted for racial profiling by police and store personnel. If so, the history of discriminatory treatment may have affected their sense of self-efficacy more than experiences on the current job. In future research on racial socialization, it will be important to ask mothers and fathers in greater depth about other experiences that may underlie feelings of self-efficacy.

Child Effects and Racial Socialization

Our moderator analyses revealed that the link between maternal self-efficacy and mothers’ racial socialization depended on whether the child had experienced discrimination: High maternal self-efficacy was connected to high racial socialization when children had experienced discrimination, but the link was not apparent when children had not experienced discrimination. Mothers may engage in racial socialization, especially preparation for bias, to help their children cope with adverse race-based treatment. This finding suggests that children's experiences may activate racial socialization in mothers particularly when they feel a sense of control over their life circumstances. It is also a reminder that parenting is not unidirectional, flowing from parent to offspring, but depends in part on input and feedback from the child (Crouter & Booth, 2003). It is also possible that the direction of effect works the other way; children who have been exposed to racial socialization may be more aware of discrimination and therefore more likely to report it. Note also that the data on children's exposure to discrimination came from offspring themselves, not from mothers, eliminating the problem with inflated associations that arises when relying on data from a single reporter. In future research, it would be useful to probe about parents’ awareness of children's encounters with discrimination and to ask parents about why they engage in racial socialization practices.

Our other moderator analyses, while not producing evidence of moderation, replicated prior work by revealing additional correlates of racial socialization (see review by Hughes et al., 2006). Specifically, mothers engaged more in both forms of racial socialization when they reported more discrimination at work and when race was more central to their identities. For fathers, the centrality of race in their identity accounted for significant variance in both cultural socialization and preparation for bias, and feeling positive about being African American was a positive correlate of cultural socialization. These findings are useful in themselves, particularly given the scant research on the correlates of racial socialization, but they also indicate that we were able to find correlates of fathers’ racial socialization. The correlates for fathers had to do with their own identities pertaining to race, not with self-direction on the job or self-efficacy.

Strengths and Limitations

This study filled some important gaps in the literature on racial socialization by examining some of processes that may connect social class to cultural socialization and preparation for bias. In addition, the investigation was unique in extending ideas about occupational socialization to African American parents’ racial socialization practices. A notable strength of the study was its focus on African American dual-earner couples. As is true in the family literature in general, the literature on African American families has paid more attention to mothers than fathers, and studies on African American dual-earner couples are scarce. Using multivariate MLM enabled us to analyze mothers and fathers as couples and to test mother-father differences in associations in a parsimonious way.

The study is not without weaknesses, however. Although having a sample of African American couples was an unusual asset which enabled us to make within family comparisons, the sampling procedure was such that we cannot gauge the representativeness of the sample. It will be important to replicate these results in larger, more representative samples. An additional limitation pertains to the reliance on parental self-report data. Although our larger study does include child outcome data reported by offspring, questions about racial socialization were asked only of parents, making it necessary, with the exception of the child exposure to discrimination variable, to rely on data from parents. This may have inflated some associations. The low internal reliability of the self efficacy measure was also problematic. Although the alpha was similarly low for both parents, the measure produced results that conformed to the hypotheses for mothers but not fathers. It is possible that the results for fathers would have been stronger had we had a better measure of self-efficacy. In future research, it will be important to measure this construct with greater precision.

Finally, we cannot determine causal associations with the data at hand; identifying causal relationships typically requires an experimental design with random assignment to conditions. Occupations are not assigned at random; individuals choose occupations they are interested in and qualify for, and they leave jobs they dislike or have difficulty handling. Similarly, employers engage in selection as they make decisions about recruitment, promotions, and lay-offs and when they engage in discrimination. Although we cannot randomly assign people to jobs, longitudinal data would be useful to rule out certain causal scenarios. For example, does occupational self-direction lead to higher self-efficacy in African American mothers, or are efficacious women selected into self-directed jobs?

Implications for the Field

Our results suggest that researchers interested in racial socialization should pay close attention to the nature of parents’ employment situations, a feature of the extra-familial context that has rarely been examined in this regard. Occupational self-direction emerged as an important construct in this study, suggesting that the workplace may be a promising site for intervention research. Jobs low in income and prestige need not be low on occupational self-direction. Semi-autonomous assembly and manufacturing work teams, for example, can transform blue collar work by providing employees with considerable opportunities for complex, self-directed activities (Crouter, 1984). One direction for future research would be to design a study in which opportunities for self-direction on the job were experimentally manipulated with the goal of testing whether such changes lead to increased feelings of self-efficacy among employees in the experimental group and, in turn, for minority parents, to greater involvement in racial socialization.

We found differences in the hypothesized processes linking social class and racial socialization for mothers versus fathers. Our results suggest that, for mothers, having opportunities to exercise self-direction on the job may lead to a sense of self-efficacy, which in turn is related to greater involvement in racial socialization practices, especially in circumstances when their children have experienced discrimination. For fathers, the conceptual chain failed to materialize; self-direction was not related to self-efficacy and self-efficacy was not related to racial socialization. Was this due to the poor measurement of self-efficacy, or does the route to racial socialization for African American fathers involve experiences other than work? What are the routes to self-efficacy for African American fathers? In future research it will be important to learn about how African American mothers and fathers negotiate their parenting roles. Do mothers orchestrate fathers’ involvement in racial socialization in ways we were unable to detect here? How do parents work it out when their values and goals differ with regard to racial socialization?

Much of the literature on the connections between work, parenting, and child development focuses on negative scenarios in which work competes for parents’ scarce time and energy (Perry-Jenkins, Repetti, & Crouter, 2000). In contrast, this study revealed a potentially positive scenario: For African American mothers, jobs that offer complexity, challenge and independence may instill feelings of efficacy that, in turn, enable them to respond effectively to their children's needs by engaging in higher levels of racial socialization.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant RO1-HD32336-02 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Ann Crouter and Susan McHale, Co-PIs).

Contributor Information

Ann C. Crouter, The Pennsylvania State University 201 Henderson Bldg. University Park, PA 16802 Phone: (814) 865-1420 Fax: (814) 863-8342 ac1@psu.edu

Megan E. Baril, The Pennsylvania State University 211 Beecher Dock House University Park, PA 16802 Phone: (814) 865-0095 mew237@psu.edu

Kelly Davis, The Pennsylvania State University 210 Beecher Dock House University Park, PA 16802 Phone: (814) 865-0095 kdavis@psu.edu

Susan M. McHale, The Pennsylvania State University 601 Oswald Tower University Park, PA 16802 Phone: (814) 865-1528 x2u@psu.edu

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist. 1989;44:1175–1184. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.44.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coard SI, Seller RM. African American families as a context for racial socialization. In: McLoyd VC, Hill NE, Dodge KA, editors. African American family life: Ecological and cultural diversity. Guilford Press; NY: 2005. pp. 264–284. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC. Participative work as an influence on human development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1984;5:71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Booth A. Children's influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Erlbaum; Mahwah: NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo H, Crnic K, Wasik B, et al. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gecas V, Seff MA. Social class, occupational conditions, and self-esteem. Sociological Perspectives. 1989;32:353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:15–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1023066418688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Chen L. When and what parents tell children about race: An examination of race-related socialization among African American families. Applied Developmental Science. 1997;1:200–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Dodge MA. African American women in the workplace: Relationships between job conditions, racial bias at work, and perceived job quality. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25:581–599. doi: 10.1023/a:1024630816168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson D, Stevenson HC. Parents’ ethnic/racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;45:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Bernal ME, Garza CA, Cota MK, Ocampo KA. Family socialization and the ethnic identity of Mexican-American children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1993;24:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn ML. Class and conformity: A study in values. 2nd ed. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn ML, Schooler C. Work and personality: An inquiry into the impact of social stratification. Ablex; Norwood, NJ: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon MC. Women, work, and well-being: The importance of work conditions. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1994;35:235–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Kim J, Burton LM, Davis KD, Dotterer AM, Swanson DP. Mothers’ and fathers’ racial socialization in African American families: Implications for youth. Child Development. 2006;77:1387–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menaghan EG, Parcel TL. Social sources of change in children's home environments: The effects of parental occupational experiences and family conditions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Miller DB, MacIntosh R. Promoting resilience in urban African American adolescents: Racial socialization and identity as protective factors. Social Work Research. 1999;23:159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Nakao K, Treas J. Updating occupational prestige and socioeconomic scores: How the new measures measure up. Sociological Methodology. 1994;24:1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Parcel TL, Menaghan EG. Parents’ jobs and children's lives. Aldine De Gruyter; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus D. Sphere-specific measures of perceived control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44:1253–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Jenkins M, Folk K. Class, couples, and conflict: Effects of the division of labor on assessments of marriage in dual-earner families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Jenkins M, Repetti RL, Crouter AC. Work and family in the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:981–998. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models. 2nd ed. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, Smith MA. Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:805–815. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology 1982. American Sociological Association; Washington, DC: 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Speight SL. Racial identity and racial socialization attitudes of African American parents. Journal of Black Psychology. 1999;25:152–170. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton MC, Chatters LM, Taylor JR, Allen WR. Sociodemographic and environmental correlates of racial socialization by Black parents. Child Development. 1990;61:401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]