Abstract

Alcohol, tobacco, and illegal drug use are pervasive throughout the world. Substance use problems are among the major contributors to the global disease burden, which includes disability and mortality. The benefits of treatment far outweigh the economic costs. Despite the availability of treatment services, however, the vast majority of people with substance use disorders do not seek or use treatment. Barriers to and unmet need for evidence-based treatment are widespread even in the United States. Women, adolescents, and young adults are especially vulnerable to adverse effects from substance abuse, but they face additional barriers to getting evidence-based treatment or other social/medical services. Substance use behaviors and the diseases attributable to substance use problems are preventable and modifiable. Yet the ever-changing patterns of substance use and associated problems require combined research and policy-making efforts from all parts of the world to establish a viable knowledge base to inform for prevention, risk-reduction intervention, effective use of evidence-based treatment, and rehabilitation for long-term recovery. The new international, open-access, peer-reviewed Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation (SAR) journal strives to provide an effective platform for sharing ideas for solutions and disseminating research findings globally. Substance use behaviors and problems have no boundaries. The journal welcomes papers from all regions of the world that address any aspect of substance use, abuse/dependence, intervention, treatment, and policy. The “open-access” journal makes cutting edge knowledge freely available to practitioners and researchers worldwide, and this is particularly important for addressing the global disease burden attributable to substance abuse.

Keywords: global burden of disease, rehabilitation, substance abuse, substance use disorders

Prevalence of substance use and substance use disorders

Substance use and substance use disorders are prevalent worldwide. Scientific evidence has consistently shown that alcohol, tobacco, and illegal drug use cause considerable morbidity and mortality.1 Results from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) World Mental Health (WMH) surveys of 17 countries reveal that substance use is pervasive throughout the world.2 As summarized in Table 1, alcohol is used by 41% to 97% of adults in their lifetimes, and tobacco products are consumed by 17% to 74% of adults. In addition, cannabis is the illicit drug most commonly used, but use varies widely from a low rate of 0.3% in the People’s Republic of China to a high lifetime rate of 42% in the United States and New Zealand. Lifetime cocaine use ranges from less than 1% in some countries to 16.2% in the United States. These country-level variations highlight that substance use is fairly heterogeneous both within a region and across countries.

Table 1.

Estimated cumulative incidence (lifetime) of substance usea

| Region | Country | Unweighted sample size | Alcohol | Tobaccob | Cannabis | Cocaine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| N | % | % | % | % | ||

| Americas | Colombia | 4426 | 94.3 | 48.1 | 10.8 | 4.0 |

| Mexico | 5782 | 85.9 | 60.2 | 7.8 | 4.0 | |

| United States | 5692 | 91.6 | 73.6 | 42.4 | 16.2 | |

| Europe | Belgium | 1043 | 91.1 | 49.0 | 10.4 | 1.5 |

| France | 1436 | 91.3 | 48.3 | 19.0 | 1.5 | |

| Germany | 1323 | 95.3 | 51.9 | 17.5 | 1.9 | |

| Italy | 1779 | 73.5 | 48.0 | 6.6 | 1.0 | |

| Netherlands | 1094 | 93.3 | 58.0 | 19.8 | 1.9 | |

| Spain | 2121 | 86.4 | 53.1 | 15.9 | 4.1 | |

| Ukraine | 1719 | 97.0 | 60.6 | 6.4 | 0.1 | |

| Middle east and Africa | Israel | 4859 | 58.3 | 47.9 | 11.5 | 0.9 |

| Lebanon | 1031 | 53.3 | 67.4 | 4.6 | 0.7 | |

| Nigeria | 2143 | 57.4 | 16.8 | 2.7 | 0.1 | |

| South Africa | 4315 | 40.6 | 31.9 | 8.4 | 0.7 | |

| Asia | Japan | 887 | 89.1 | 48.6 | 1.5 | 0.3 |

| People’s Republic of China | 1628 | 65.4 | 53.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

| Oceania | New Zealand | 12790 | 94.8 | 51.3 | 41.9 | 4.3 |

Notes:

Data from Degenhardt L, Chiu WT, Sampson N, et al. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2008;5(7):e1412

Tobacco includes cigarettes, cigars, and pipes.

Globally, it has been estimated that 3.5% to 5.7% of the population aged 15 to 64 years, or approximately 155 to 250 million people, had used an illicit drug at least once in the past year.3 When taking into account the pattern of use, an estimated 16 to 38 million people are considered problem drug users (regular or frequent users), and 11 to 21 million people are injection drug users. This wide range of estimations is related, in part, to a lack of reliable epidemiological data on use of specific drugs other than marijuana (eg, inhalants, cocaine/crack, amphetamines/methamphetamine, hallucinogens, ecstasy/MDMA [3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine], sedatives, tranquilizers, heroin, and opioid analgesics), especially in countries where resources for research and evidence-based treatment are comparatively limited but illicit drug use has increased.3,4 In particular, research is needed to monitor and investigate the extent of health problems associated with misuse and abuse of prescription drugs in both adolescents and adults.5,6 Misuse and abuse of prescription drugs, especially analgesic opioids, has become an epidemic in the United States.5 In developing countries, this public health concern may be complicated further by issues of nonpharmacy (black market) sales of pharmaceuticals, marketing of counterfeit drugs, and self-treatment with pharmaceuticals.

As with substance use, substance use disorders (ie, abuse or dependence) do not distribute equally across countries. Estimates of alcohol/drug use disorders assessed by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) from 6 countries (Brazil, Canada, Germany, Mexico, Netherlands, and the United States) are listed in Table 2. Approximately 10% to 28% of nonelderly adults had a history of alcohol or drug use disorders in their lifetimes, and an estimated 6% to 13% had an alcohol or drug use disorder in the past 12 months.7 These data suggest that personal and societal problems associated with alcohol/drug use disorders are highly prevalent among nonelderly adults in many countries worldwide because substance addiction in general is a chronic condition with a high rate of relapse.8,9 However, the true extent of substance use disorders is much larger than these estimates suggest because they do not include nicotine (tobacco) dependence.

Table 2.

Prevalences of DSM-III-R alcohol or drug use disordersa

| Country | Brazil | Canada | Germanyb | Mexico | Netherlands | USA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, n | 1464 | 6261 | 1626 | 1734 | 7076 | 5388 |

| Age in years | ≥18 | 18–54 | 18–25 | 18–54 | 18–64 | 18–54 |

| Alcohol or drug disorder | % | % | % | % | % | % |

| Lifetime disorder | 16.1 | 19.7 | 21.5 | 9.6 | 18.7 | 28.2 |

| 12-month disorder | 10.5 | 7.9 | 13.2 | 5.8 | 8.9 | 11.5 |

Notes:

Data from WHO International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Cross-national comparisons of the prevalences and correlates of mental disorders. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(4):413–4267

DSM-IV criteria were used in Germany.

Globally, there are an estimated 1.3 billion tobacco smokers, and half of them (or approximately 650 million smokers) are expected to die prematurely of a tobacco-related disease.10 Unless effective preventive interventions are implemented widely, the number of tobacco smokers will rise to 1.7 billion by 2025.10 In the United States, nicotine dependence is the most prevalent substance addiction, with an estimated 13% of American adults with nicotine dependence in the past year – a figure that is close to twice the estimate of the most common nonaddictive disorder, major depression (7%).11 Nicotine dependence also is highly comorbid with alcohol/drug use and other mental disorders (eg, depression),12,13 and longitudinal data have shown that tobacco smoking increases the risk for the subsequent onset of depression.13,14 Comorbidities not only exacerbate adverse health risks but also complicate treatment strategies aiming to promote smoking cessation. Disappointingly, only 9% of countries worldwide mandate smoke-free bars and restaurants, and 65 countries report no implementation of any smoke-free policies on a national level.15 Given the scarcity of reliable international data about nicotine dependence, a better understanding of the nature and extent of nicotine dependence across countries using a standardized diagnostics tool is clearly warranted.

Cross-national survey estimates of substance use and disorders may underestimate actual use and disorders as surveys of the general population typically do not include some demographic subgroups that are vulnerable to substance use and consequences, including psychiatric or addiction patients who are in residential treatment centers, people who are in jails or prisons, and homeless people. The results also are influenced by differential levels of participation and nonresponse rates across countries.2 Additionally, due to the very high cost of surveying a large sample in any cross-national study, empirical data on cross-national estimates for drug-use problems other than marijuana are limited, which hinders the development of effective public health policy, prevention efforts, and treatment strategies. Nevertheless, studies on specific class of drug use or abuse other than marijuana in at-risk subgroups (eg, clinical patients, substance users, people who have involvement with the criminal justice system, regular club/party attendees, or those who have engaged in risky sexual behaviors) can provide useful evidence to inform future research and intervention efforts. The need for such research is clear.

Substance use and global burden of disease

Substance use problems are among the leading contributors to the global burden of disease. The magnitude of societal burden resulting from substance abuse is enormous. Substance abuse not only affects personal health and accomplishments, but also negatively affects the quality of life of abusers’ family members (eg, financial security, mental health, social networks, and productivity) and the functioning of society at large (eg, the criminal justice and health care systems). For example, in the United States, the direct and indirect economic cost to individual users, their families, and society was estimated to be $21.9 billion for heroin addiction and $184.6 billion for alcohol use problems per year.16,17 Indeed, problems associated with substance abuse are so pervasive that they can affect nearly every aspect of the abuser’s life. These problems may include: employment issues, injuries, violence, assaults, child neglect or abuse, incarceration, suicidal behaviors, psychiatric disorders, cognitive impairments, transmission of sexually transmitted diseases (eg, HIV/AIDS), damage to multiple organs (eg, respiratory, immune, digestive, cardiovascular, reproductive, and pancreatic systems), and mortality.1,16,17 In particular, substance use-related behaviors are a major contributor to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, either through sharing of injection equipment or substance use-related risky/unprotected sexual behavior.

Women are especially vulnerable to adverse effects from substance abuse, either from family members who abuse substances (eg, children and husband) or their own substance abuse behaviors.18 For example, male drug users create enormous burdens for affected women, including financial stress, emotional and psychological distress, guilt or shame, violence, physical or sexual abuse, and transmission of HIV/AIDS. Substance abuse per se, however, has an even greater impact on women. Some female substance abusers reportedly progress even faster than men from initial use to needing treatment, and they face additional barriers and stigma in receiving treatment, partially due to sex-related biological and psychosocial differences in stress reactivity as well as to cultural role constraints such as unequal power, child care responsibilities, limited financial resources, and educational disparities.18–20 These differences emphasize the need for gender-specific psychosocial and educational interventions in addition to standard treatment for addiction to address woman-specific concerns (eg, empowerment, childcare, transportation, or other mental health concerns).21,22 Unfortunately, there is increasing evidence in the United States and elsewhere indicating an upward trend of substance use in the young female population, and the male-female gap in substance use is reportedly closing in on the young cohorts.2,19

Substance use – including use of alcohol, tobacco, and other illicit or nonprescribed drugs – is among the leading contributors to the burden of diseases reported in the WHO’s Global Health Risks report.23 Based on The Global Burden of Disease report,24 alcohol and drug use disorders are among the leading causes of moderate and severe disability in the world, with an estimated 40.5 million people with moderate or severe disability related to alcohol use problems and an estimated 11.8 million people with moderate or severe disability related to drug use problems in 2004. In terms of burden of disease measured by disability-adjusted life years (eg, the loss of healthy years of life), HIV/AIDS is ranked the fifth and alcohol use disorders the seventeenth leading contributor to burden of disease in the world.24 When the income of a country is considered, HIV/AIDS is ranked the third and the seventh leading contributor to burden of disease in low- and middle-income countries, respectively; alcohol use disorders are ranked the eighth and the fifth leading contributors to burden of disease in middle- and high-income countries, respectively. Moreover, HIV/AIDS disproportionally leads to the loss of healthy years of life for women of child-bearing age in low- and middleincome countries, while alcohol use disorders are among the major contributors to the loss of healthy years of life for women in high-income countries.24

Of all substances used, tobacco may have the biggest impact on mortality around the world. There is no safe level of exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke, but one-third of adults globally are regularly exposed to second-hand tobacco smoke, and about 40% of all children worldwide (an estimated 700 million children) are exposed to second-hand tobacco smoke at home.15 Secondhand tobacco smoke is estimated to cause about 600,000 premature deaths per year worldwide (mainly women and children).15 Overall, tobacco use contributes to several leading diseases such as lung cancer, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.24,25 On an international level, tobaccoattributable deaths are projected to rise from 5.4 million in 2005 to 6.4 million in 2015 and 8.3 million in 2030.25 Specifically, tobacco is projected to kill 50% more people in 2015 than HIV/AIDS and to be responsible for 10% of all deaths globally. By 2030, tobacco-related diseases and HIV/AIDS are expected to be the leading causes of deaths globally. The rise in tobacco-attributable deaths is mainly confined to low- and middle-income countries. Sadly, tobacco-related diseases and HIV/AIDS are projected to become the leading sources of disease burden in these struggling countries as well.25

Need for research and timely intervention

Barriers to and unmet need for substance abuse treatment are widespread. The benefits of treatment far outweigh their economic costs.26 Despite the availability of treatment services for substance abuse, however, the vast majority of people with substance use disorders do not seek or use treatment.27 Data from a national survey of noninstitutionalized civilian adults in the United States show that just 38% of people with a 12-month alcohol/drug use disorder reported the receipt of any mental health or substance abuse services in the past year.28 Results from the International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology surveys also demonstrate a generally low rate of treatment use. In Canada and the United States, 22% of adults with alcohol/drug or other mental disorders in the previous year used any mental health or substance abuse service in the past 12 months; in the Netherlands, 32% did so.7 Regrettably, while adolescents and young adults are particularly likely to be active substance abusers, to engage in risky sexual behaviors, and to be affected by substance use problems, they are much less likely to receive substance abuse treatment or to perceive a need for it.29–32 Such striking unmet need for substance abuse treatment is complicated further by findings that nonfinancial psychological factors (eg, stigma, fear of rejection, and denial of having substance abuse problems) and a general lack of knowledge about where to get help constitute major barriers that keep people with substance use problems from seeking treatment services.29,30,33 Therefore, the need for public health campaigns and educational programs to increase the general populations’ knowledge of adverse effects from substance abuse and of treatment resources are warranted. Substance use in adolescence not only increases the risk for subsequent addiction and other medical/psychiatric problems, but also may produce long-lasting adverse effects on the developing brain; adolescence is hence a critical time for intervention to prevent serious addiction and its consequences.31,32

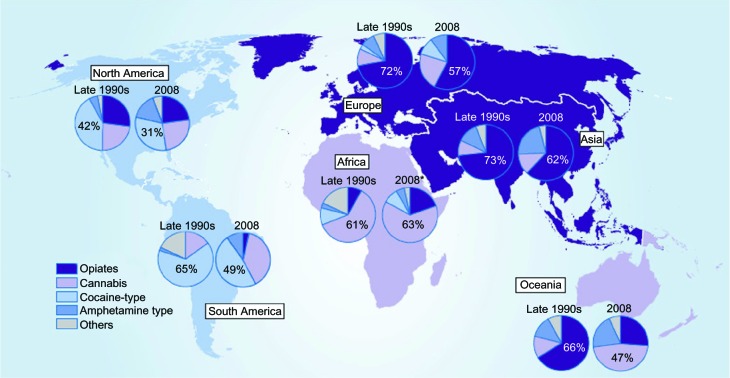

Substance use behaviors, as well as the disability and mortality attributable to substance use, are preventable and modifiable. Concerted research and intervention efforts from all parts of the world are needed to address this complex, global, and interconnected public health issue. As revealed in Figure 1, substance use is not a static phenomenon.3 In the late 1990s, the main drugs of problematic use as measured by treatment demand were cocaine in North and South America, cannabis in Africa, and opiates in Europe, Asia, and Oceania. These patterns have changed over time. In 2008, the treatment demand for abuse of cocaine in North and South America has decreased, but the demand for treatment has increased for abuse of amphetamines (including methamphetamines) in North and South America and for abuse of cannabis in South America. Likewise, the demand for treatment related to abuse of opiates has decreased in Europe, Asia, and Oceania in the past decade, whereas the demand for treatment is estimated to have increased for abuse of amphetamines (in Asia and Oceania), cannabis (in Europe and Oceania), and cocaine (in Europe). In Africa, the demand for treatment related to abuse of cannabis remains high, but the demand for treatment related to abuse of opiates also has increased.3

Figure 1.

Main problem drugs as reflected in treatment demand, by region, from the late 1990s to 2008 (or latest year available).

Data from United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2010),3 Annual Reports Questionnaire Data/DELTA and National Government Reports. Percentages are unweighted means of treatment demand from reporting countries. Number of countries reporting data for 2008: Europe (45); Africa (26); North America (3); South America (24); Asia (42); Oceania (2). Data generally account for primary drug use; polydrug use may increase totals beyond 100%. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Notes: *Treatment data dating back more than 10 years were removed from the 2008 estimates, and therefore caution should be used when comparing the data from 2008 with previous years.

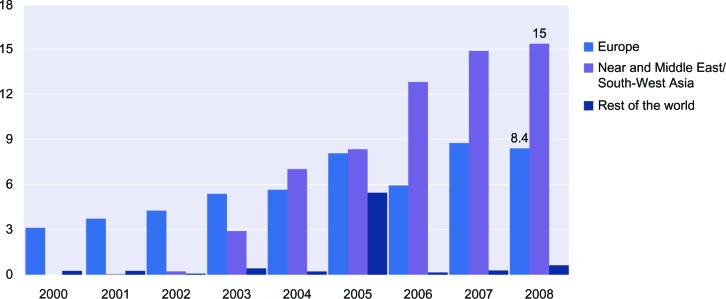

Of a particular concern is the increased rate of amphetamine-type drug use in East and Southeast Asia, North America, Mexico, some European countries, South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia.4 As demonstrated in Figure 2, global seizures of amphetamines reached a peak in 2007–2008 (24.3 metric ton’s in 2008); Near and Middle East/Southwest Asia and Europe together accounted for 97% of seizures in 2008.3 This growing rate of amphetamine use in Near and Middle East/Southwest Asia is a cause of concern for several reasons. Amphetamine users not only can develop amphetamine dependence syndrome, drug-induced psychotic episodes, and cardiovascular or cerebrovascular toxicity, but also are at elevated risk for transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases through injection of methamphetamine and other drugs, as well as through the practice of unprotected or risky sexual behaviors.4 Unfortunately, in-depth review of global evidence leads one to conclude that good epidemiological data on the extent, use patterns, risk profiles, natural history of use, interactions with other risky behaviors and environment contexts, and intervention efforts for amphetamine use are generally lacking in countries where amphetamine use has increased.4

Figure 2.

Regional breakdown of global amphetamine seizures, 2000–2008 (ton equivalents).

Data from United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2010).3

Taken together, the ever-changing profiles of substance use and associated problems require combined research and policy-making efforts from all parts of the world to establish a viable knowledge base to inform early screening, prevention, risk-reduction intervention, effective use of evidence-based treatment, and rehabilitation for long-term recovery. A concerted investment in research is needed. Research activities are necessary to monitor the emerging trends in patterns of varying substance use; to identify the distributions and potential causes of use by time, people, place, and location; to develop effective prevention and treatment strategies; to elucidate mechanisms to reduce barriers to treatment-seeking; to apply incentives to improve treatment retention and rehabilitation; and to implement culturally acceptable public health policies that will reduce the burden of diseases attributable to substance use problems.

Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation as a platform for disseminating knowledge and solutions

Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation is interested in papers on all aspects of substance use and abuse research, as well as options for prevention, risk-reduction intervention, treatment, and rehabilitation. This new international, open-access, peer-reviewed journal provides an effective platform for sharing ideas for solutions and disseminating research findings globally. The “open-access” journal makes cutting edge knowledge freely available to practitioners and researchers worldwide, and this is particularly important for addressing global burden of disease attributable to substance abuse. The journal publishes original research, literature reviews, editorials, case reports, evidence-based practices, and commentaries. Substance use behaviors and problems have no boundaries. We welcome papers from all regions of the world and any field of science (eg, psychology, sociology, medicine, psychiatry, social work, law, forensics, health policy, community health, public health, education, criminal justice, anthropology, pharmacology, psychopharmacology, and biostatistics). Our editorial board represents an experienced group of scientists from a wide range of disciplines and regions. The journal will strive for rapid turn-around time, high quality of reviewer comments, and objectivity. Finally, the benefits of publishing with Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation are unlimited: every scientist, policymaker, health care professional, parent, and concerned citizen can read your work free of charge, and you keep the copyright.

Acknowledgments

Dr Wu has received research support from the US National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (R21DA027503, R33DA027503, R01DA019623, and R01DA019901 to Li-Tzy Wu; R01DA026652 to William W. Eaton; and HSN271200522071C to Dan G. Blazer). The sponsoring agency had no further role in the writing of the paper. The opinions expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The author thanks Dr Dan G. Blazer for his valuable comments on the initial draft, Ms Amanda McMillan for her editorial assistance, and three anonymous reviewers for their thorough reviews and comments.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author discloses no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Brick J. Handbook of the Medical Consequences of Alcohol and Drug Abuse. New York: The Haworth Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Degenhardt L, Chiu WT, Sampson N, et al. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2008;5(7):e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) World Drug Report 2010 New York: United Nations; 2010http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/WDR-2010.htmlAccessed 2010 Sep 27 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reference Group to the United Nations on HIV and Injecting Drug Use . The Global Epidemiology of Methamphetamine Injection: A Review of the Evidence on Use and Associations with HIV and Other Harm. Sydney, Australia: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez SH, Nelson LS. Prescription drug abuse: insight into the epidemic. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88(3):307–317. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu LT, Pilowsky DJ, Patkar AA. Non-prescribed use of pain relievers among adolescents in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94(1–3):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology Crossnational comparisons of the prevalences and correlates of mental disorders. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(4):413–426. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose JE. Stress alleviation and reward enhancement: two promising targets for relapse prevention. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(8):687–688. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss F. Neurobiology of craving, conditioned reward and relapse. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization The facts about smoking and health http://www.wpro.who.int/media_centre/fact_sheets/fs_20060530.htmAccessed 2010 Sep 27

- 11.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, Stinson FS, Dawson DA. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Leon J, Becoña E, Gurpegui M, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Diaz FJ. The association between high nicotine dependence and severe mental illness may be consistent across countries. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(9):812–816. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, Chilcoat HD, Andreski P. Major depression and stages of smoking. A longitudinal investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(2):161–166. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu LT, Anthony JC. Tobacco smoking and depressed mood in late childhood and early adolescence. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(12):1837–1840. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.12.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization WHO Report on Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2009: implementing smoke-free environments Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2009/gtcr_download/en/index.htmlAccessed 2010 Sep 27 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harwood H. Updating Estimates of the Economic Costs of Alcohol Abuse in the United States: Estimates, Update Methods, and Data. Bethesda, MD: The Lewin Group for the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mark TL, Woody GE, Juday T, Kleber HD. The economic costs of heroin addiction in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;61(2):195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . Women and Drug Abuse: The Problems in India. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenfield SF, Back SE, Lawson K, Brady KT. Substance abuse in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33(2):339–355. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith BD, Marsh JC. Client-service matching in substance abuse treatment for women with children. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22(3):161–168. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashley OS, Marsden ME, Brady TM. Effectiveness of substance abuse treatment programming for women: a review. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29(1):19–53. doi: 10.1081/ada-120018838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalHealthRisks_report_full.pdfAccessed 2010 Sep 27 [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization The global burden of disease: 2004 update Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/index.htmlAccessed 2010 Sep 27 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment Cost offset of treatment services Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2009https://www.samhsa-gpra.samhsa.gov/CSAT/view/docs/SAIS_GPRA_CostOffsetSubstanceAbuse.pdfAccessed 2010 Sep 27 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu LT, Kouzis AC, Leaf PJ. Influence of comorbid alcohol and psychiatric disorders on utilization of mental health services in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1230–1236. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu LT, Ringwalt CL. Use of alcohol treatment and mental health services among adolescents with alcohol use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(1):84–92. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu LT, Pilowsky DJ, Schlenger WE, Hasin D. Alcohol use disorders and the use of treatment services among college-age young adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(2):192–200. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.2.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bava S, Frank LR, McQueeny T, Schweinsburg BC, Schweinsburg AD, Tapert SF. Altered white matter microstructure in adolescent substance users. Psychiatry Res. 2009;173(3):228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Institute on Drug Abuse . Drugs, brains, and behavior: the science of addiction. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. NIH Pub No. 07-5605. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu LT, Ringwalt CL. Alcohol dependence and use of treatment services among women in the community. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(10):1790–1797. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.10.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]