Abstract

Patients with post-Lyme disease syndrome (PLDS) report persistent symptoms of pain, fatigue, and/or concentration and memory disturbances despite antibiotic treatment for Lyme borreliosis. The etiopathogenesis of these symptoms remains unknown and no effective therapies have been identified. We sought to examine the antiborrelia antibody profile in affected patients with the aim of finding clues to the mechanism of the syndrome and its relationship to the original spirochetal infection. Serum specimens from 54 borrelia-seropositive PLDS patients were examined for antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi proteins p18, p25, p28, p30, p31, p34, p39, p41, p45, p58, p66, p93, and VlsE by automated immunoblotting and software-assisted band analysis. The presence of serum antibodies to the 31-kDa band was further investigated by examination of reactivity against purified recombinant OspA protein. Control specimens included sera from 14 borrelia-seropositive individuals with a history of early localized or disseminated Lyme disease who were symptom free (post-Lyme healthy group), as well as 20 healthy individuals without serologic evidence or history of Lyme disease. In comparison to the post-Lyme healthy group, higher frequencies of antibodies to p28 (P < 0.05), p30 (P < 0.05), p31 (P < 0.0001), and p34 (P < 0.05) proteins were found in the PLDS group. Assessment of antibody reactivity to recombinant OspA confirmed the presence of elevated levels in PLDS patients (P < 0.005). The described antiborrelia antibody profile in PLDS offers clues about the course of the antecedent infection in affected patients, which may be useful for understanding the pathogenic mechanism of the disease.

INTRODUCTION

Lyme disease is the most commonly reported tick-borne infection in the United States and is also endemic in Europe and parts of Asia (21, 25). It is caused by bacteria of the Borrelia burgdorferi species complex (23). The early phase of the infection is typically associated with a characteristic skin lesion, known as erythema migrans (EM), in the localized stage and with multiple (secondary) EM lesions in the disseminated stage (4). Extracutaneous manifestations of disseminated and late disseminated Lyme disease may affect the joints, heart, and/or the nervous system (24, 29). The most frequent objective neurologic complications include lymphocytic meningitis, cranial neuropathy, and radiculopathy, which usually respond well to antibiotic treatment (12). However, some patients complain of persistent or relapsing symptoms despite treatment and in the absence of objective clinical or microbiologic evidence of ongoing infection, as determined by currently available methods (11, 20). The symptoms in these patients include mild to severe musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, and/or difficulties with concentration and memory (11, 20). The condition, referred to as post-Lyme disease syndrome (PLDS or PLS) or chronic Lyme disease, can be associated with considerable impairment in the health-related quality of life in the affected patient population (16).

Despite several years of debate and a number of treatment trials (10, 16, 17) few clues to the cause of the symptoms of PLDS have emerged. A lack of biomarkers that would correlate with symptoms or treatment outcome in patients has also compounded the problem of understanding the syndrome. There have been no studies to date that systematically examine the antigen specificity of the antiborrelia immune response in patients with a history of Lyme disease and persistent symptoms. In this study, we sought to gain clues to the mechanism of PLDS and its relationship to the original B. burgdorferi infection by characterizing the antigen specificity of antiborrelia antibodies in seropositive patients and control subjects. The described pattern of immune reactivity to proteins of B. burgdorferi may help in better understanding the course of preceding acute infection and in gaining clues about the pathogenic mechanism of the syndrome in a large subset of PLDS patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Serum samples were from 54 individuals with PLDS who were seropositive by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for IgG antibodies to B. burgdorferi. Table 1 shows patient group characteristics; see below for the assay procedure. The source of samples and selection criteria have been previously described in detail (6, 16). Of the 54 specimens analyzed, 34 were from patients who had a history of single or multiple EM. Documentation by a physician of previous treatment of acute Lyme disease with a recommended antibiotic regimen was also required. Patients had one or more of the following symptoms at the time of enrollment: widespread musculoskeletal pain, cognitive impairment, radicular pain, paresthesias, or dysesthesias. Fatigue often accompanied one or more of these symptoms. The chronic symptoms had to have begun within 6 months after the documentation of infection with B. burgdorferi.

Table 1.

Subject group characteristics

| Subject group | History of Lyme disease manifestation prior to treatment | No. of subjects | No. female: no. male | Mean age (yr) ± SD | Mean time (yr) since documentation of infection ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLDS | 54 | 25:29 | 56.3 ± 12.8 | 4.72 ± 2.81 | |

| EM | 34 | 16:18 | 54.4 ± 11.8 | 4.89 ± 2.87 | |

| Single EM | 24 | 11:13 | 54.0 ± 10.5 | 4.96 ± 2.97 | |

| Multiple EM | 10 | 5:5 | 55.4 ± 15.1 | 4.71 ± 2.77 | |

| Othera | 20 | 9:11 | 59.5 ± 14.0 | 4.42 ± 2.76 | |

| Post-Lyme healthy | EM | 14 | 4:10 | 51.4 ± 18.0 | 4.61 ± 3.50 |

| Single EM | 7 | 0:7 | 48.0 ± 13.3 | 4.32 ± 3.98 | |

| Multiple EM | 7 | 4:3 | 54.4 ± 21.8 | 4.86 ± 3.34 | |

| Non-Lyme healthy | 20 | 12:8 | 49.7 ± 15.5 |

Non-erythema migrans (EM) manifestations of Lyme disease, including those associated with late Lyme disease, such as in Lyme arthritis and late neurologic Lyme disease.

The study also included control serum specimens from 14 borrelial IgG ELISA-seropositive individuals who had been treated for early localized or disseminated Lyme disease associated with single or multiple EM with no post-Lyme symptoms after at least 2 years of follow-up (post-Lyme healthy group) (patient group characteristics are shown in Table 1). The original diagnosis of acute Lyme disease in these currently healthy subjects was confirmed by recovery of B. burgdorferi in cultures of skin and/or blood. The source of samples and selection criteria were previously described (6).

Serum samples from 20 healthy subjects without history or serologic evidence of past or present Lyme disease (non-Lyme healthy group) were also included in the study. In addition, serum specimens from two individuals who were vaccinated for Lyme disease with the recombinant OspA protein (Lymerix) were used as positive controls for experiments aimed at determination of the anti-OspA antibody response. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Weill Cornell Medical College of Cornell University.

Antiborrelia antibodies. (i) B. burgdorferi ELISA.

IgG antiborrelia antibody levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (6).

(ii) B. burgdorferi WB.

The IgG antibody response to B. burgdorferi B31 was further characterized by Western blot assay (WB), using commercial prepared blots and the Euroblot automated WB instrument according to the manufacturer's protocols (Euroimmun, Boonton, NJ). Briefly, nitrocellulose strips containing electrophoresis-separated B. burgdorferi B31 proteins were blocked and then incubated with 1.5 ml of diluted serum sample (1:50) for 30 min. Membrane strips were washed and incubated with alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-human IgG antibody for 30 min. Bound antibodies were detected using the nitroblue tetrazolium chloride–5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolylphosphate (NBT-BCIP) staining system (Euroimmun). Quantitative analysis of bands on each blot was carried out using the EUROLineScan software (Euroimmun). Accurate background correction and determination of cutoff values for positivity were carried out by the software for the p18, p25 (OspC), p28, p30, p31 (OspA), p34 (OspB), p39 (BmpA), p41 (FlaB), p45, p58, p66, p93, and recombinant VlsE borrelial protein bands. Determination of IgG-positive serology for Lyme disease was based on the CDC criteria, according to which an IgG immunoblot can be considered positive if 5 or more of the following 10 bands are positive: 18 kDa, 25 kDa (OspC), 28 kDa, 30 kDa, 39 kDa (BmpA), 41 kDa (Fla), 45 kDa, 58 kDa, 66 kDa, and 93 kDa (1, 5).

(iii) OspA ELISA.

Round-bottom 96-well polystyrene plates (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) were incubated with 0.5 μg/well of B. burgdorferi recombinant OspA protein (Meridian Life Science, Saco, ME) in 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) (1.5 h, 37°C). Control wells were not coated. Wells were washed and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) (1.5 h). Incubation with diluted serum specimens (50 μl/well at 1:400 in blocking solution) was done for 1 h. Serum samples from two OspA-vaccinated individuals were included as controls on each plate. Incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep anti-human IgG secondary antibody (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) (1:2,000 in blocking solution) was done for 1 h. Incubation with developing solution, comprising 27 mM citric acid, 50 mM Na2HPO4, 5.5 mM o-phenylenediamine, and 0.01% H2O2 (pH 5), was done for 20 min. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm and corrected for nonspecific binding by subtraction of the mean absorbance of corresponding wells not coated with the OspA protein. Absorbance values were normalized based on the mean for the positive controls on each plate. The cutoff for positivity was assigned as three standard deviations above the mean for the results for the non-Lyme healthy group.

Data analysis.

Group differences were analyzed by the two-tailed Welch t test or Mann-Whitney U test (continuous data) and the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test (nominal data). Differences with P values of <0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Subjects.

There was not a significant difference in age, gender, or elapsed time since infection between the PLDS patient group and the post-early Lyme healthy control group (Table 1).

B. burgdorferi ELISA.

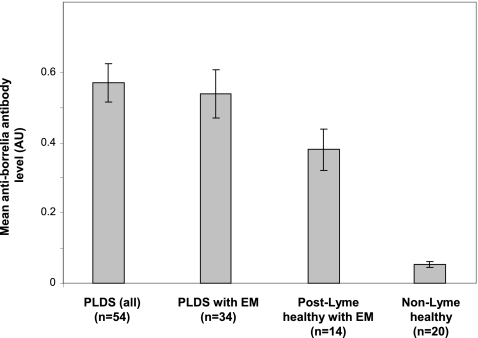

While all selected post-Lyme samples were seropositive, the mean antiborrelia antibody level (as measured by mean normalized absorbance) was higher for the PLDS group than the post-early Lyme healthy group (P < 0.05). The difference remained weakly significant when the comparison was limited to those individuals who had presented with EM in each group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). None of the specimens from the non-Lyme healthy control group was positive.

Fig. 1.

IgG antiborrelia antibody levels in PLDS patients and control subjects, as measured by ELISA. While all post-Lyme disease samples were positive by ELISA, the mean antiborrelia antibody level (mean normalized absorbance at 450 nm) was higher for the PLDS group (n = 54) than for the post-early Lyme healthy group (n = 14) (P < 0.05). The difference remained significant when the analysis was limited to specimens from individuals with a history of EM in both groups (n = 34 for PLDS versus n = 14 for post-Lyme healthy) (P < 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean for each group.

B. burgdorferi Western blot.

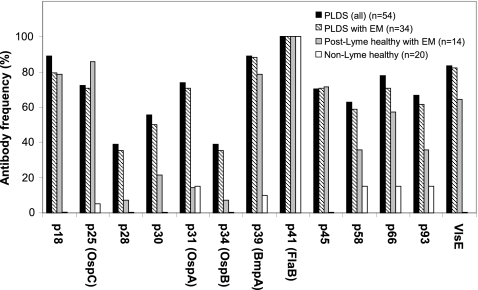

Forty-seven of 54 ELISA-positive PLDS subjects (87.0%) and 11 of 14 ELISA-positive post-early Lyme healthy subjects (78.6%) were found to be IgG seropositive for antiborrelia antibodies by immunoblotting as determined by the software and according to the CDC criteria. None of the healthy control subjects without a history of Lyme disease was positive by WB. Significantly more PLDS patients were found to have antibodies to p28 (P < 0.05), p30 (P < 0.05), p31 (P < 0.0001), and p34 (P < 0.05) proteins than post-Lyme healthy subjects (Fig. 2). When only those in each group with a history of presenting with EM were compared, there was a significantly higher number of PLDS patients with antibodies to p31 (P < 0.001), while the difference for the number of individuals with antibody reactivity to p28 and p34 approached significance (P = 0.07). In contrast, the frequencies of antibody reactivity to p18, p25, and p45 were either comparable or slightly higher in the post-Lyme healthy group. Frequencies of antibody reactivity to all bands, with the exception of p41, were significantly higher in the PLDS group than in the group of healthy individuals without history or serologic evidence of Lyme disease.

Fig. 2.

Frequencies of positivity for IgG antibodies to B. burgdorferi WB bands in PLDS patients and control subjects. Significantly more PLDS patients (n = 54) were found to have antibodies to p28 (P < 0.05), p30 (P < 0.05), p31 (P < 0.0001), and p34 (P < 0.05) bands than post-Lyme healthy subjects (n = 14). When only those who had presented with EM in the two groups were compared (n = 34 for PLDS versus n = 14 for post-Lyme healthy), there was a significantly higher frequency of PLDS patients with antibodies to p31 (P < 0.001), while the difference for the frequency of individuals with antibody reactivity to p28 and p34 approached significance (P = 0.07).

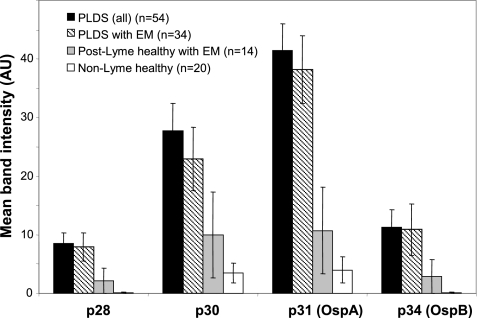

The significant differences in antibody reactivity to the four bands mentioned above were confirmed by comparing the means for the software-calculated band signal intensities (gray-level intensities) for each group. There was a higher mean band intensity for p28 (P < 0.05), p30 (P < 0.05), p31 (P < 0.005), and p34 (P < 0.05) in the PLDS group than in the post-Lyme healthy group (Fig. 3). The difference in mean band intensity for p31 remained significant when only those in each post-Lyme group with a history of EM were compared (P < 0.005).

Fig. 3.

Levels of IgG antibody reactivity to 28-, 30-, 31-, and 34-kDa proteins of B. burgdorferi in PLDS patients and control subjects. Means for the software-calculated WB band signal intensities for antibody reactivity with the four proteins were compared between ELISA-seropositive PLDS patients, ELISA-seropositive post-early Lyme healthy subjects, and healthy individuals without history or serologic evidence of Lyme disease. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean for each group.

OspA ELISA.

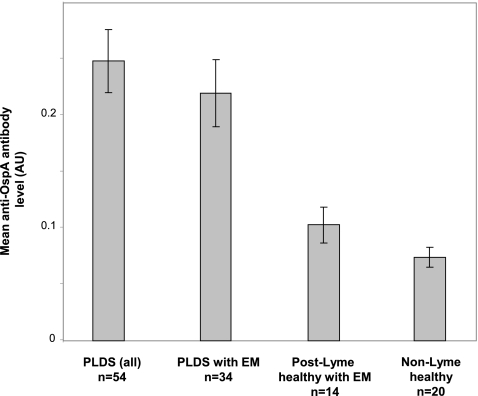

The observed differential antibody reactivity to p31 in PLDS patients by WB was further investigated by ELISA, using purified recombinant OspA protein. The mean antibody reactivity (as measured by mean normalized absorbance) to OspA in PLDS patients was significantly higher than that in post-early Lyme healthy individuals (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4). The difference remained significant when considering only those in each group who had presented with EM (P < 0.005). Similarly, the frequency of anti-OspA antibody positivity in PLDS patients (27 of 54; 50.0%) was significantly greater than that in post-Lyme healthy individuals (1 of 14; 7.1%) (P < 0.05). The difference remained significant when the analysis was limited to those in the PLDS and post-Lyme healthy groups who had a history of presenting with EM (15 of 34 versus 1 of 14; 44.1% versus 7.1%) (P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

IgG anti-OspA antibody levels in PLDS and control subjects, as measured by ELISA. The mean antiborrelia antibody level (mean normalized absorbance at 450 nm) was higher for the PLDS group (n = 54) than for the post-early Lyme healthy group (n = 14) (P < 0.0001). The difference remained significant when the analysis was limited to specimens from individuals with a history of EM in both groups (n = 34 for PLDS versus n = 14 for post-Lyme healthy) (P < 0.005). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean for each group.

DISCUSSION

The controversy surrounding PLDS is partially caused by our limited knowledge about the etiology and pathology of the syndrome. A potential source of information about PLDS, namely, the specificity of the immune response to B. burgdorferi in affected patients, has not been systematically characterized before. The availability of serum specimens from 54 seropositive patients fulfilling strict criteria for PLDS provided the opportunity to examine the respective antiborrelia antibody profiles in detail. The data in this report suggest that a defined pattern of antibody reactivity to borrelial antigens in PLDS may exist and offer novel clues about the etiopathogenesis of the syndrome and its relationship to the original spirochetal infection.

We can consider some possibilities that would explain the observed antiborrelia antibody response in PLDS and help in understanding its significance and pathogenic relevance to the syndrome. First, it is important to note that the apparently higher overall antiborrelia antibody response in PLDS was not evenly distributed toward the various B. burgdorferi immunodominant proteins. We observed higher-than-expected frequencies of antibody reactivity to p28, p30, p31, and p34 protein bands in the patient group than in the post-early Lyme healthy group, while the frequencies of antibody reactivity to p18, p25, p39, and p45 were either comparable or slightly higher in the post-early Lyme healthy group. Previous studies have shown that IgG antibodies to p25, p39, and p45 are generated early in Lyme disease, whereas antibodies against p30, p31, and p34 are more frequent in later stages of infection (2, 8, 14, 19, 22). The IgG antibody response to p31 (OspA), a protein whose expression by the B. burgdorferi spirochete diminishes in the early stage of the infection, is particularly rare during this phase but becomes more common in late Lyme disease (1, 2, 9, 15). Accordingly, the observed antibody profile, especially the significantly higher antibody reactivity toward the p31 band on WB and toward the recombinant OspA protein on ELISA in the PLDS group, may be indicative of a longer-than-assumed course of active infection in affected patients. This may have been caused by a delay in the start of the appropriate course of antibiotic treatment and/or an undocumented repeat infection(s) in many PLDS patients. This finding would be in line with previous studies indicating that delayed treatment is associated with increased post-Lyme disease symptoms (20).

Second, the observed antibody response may be indicative of persisting attenuated forms of the organism or spirochetal debris in certain tissues after antibiotic treatment and/or ongoing presence of certain borrelial antigens, possibly retained by antigen-presenting cells, in some PLDS patients. In fact, several studies have demonstrated the persistence of spirochetal DNA or apparently noninfectious forms of the organism in some antibiotic-treated animals (3, 13, 26, 27). One can postulate that while these spirochetal forms or specific antigen remnants of the organism would not be responsive to antibiotic treatment, they might continue to elicit a significant antibody response.

Third, the pattern of antiborrelia antibody reactivity in PLDS may be indicative of differences in host condition, as local environmental changes can affect protein expression by the B. burgdorferi spirochete. For example, it has been shown that the expression of OspA by B. burgdorferi is significantly increased when inflammation is induced in mice during early infection (7). Therefore, the increased antibody response to OspA in PLDS patients, even in those who had presented with EM, may be indicative of the concurrent presence of an inflammatory condition during the antecedent infection.

Finally, it is conceivable that certain strains of B. burgdorferi can induce higher levels of antibodies against particular antigens in susceptible individuals. Recent work points to the existence of multiple strains of the organism in the United States, most of which have not been studied with regard to their immunogenic potential or specific protein expression levels after introduction into the mammalian host (18, 28, 30, 31). Therefore, the observed differences in the specificity of the antiborrelia antibody response might be attributed to the higher likelihood of antecedent infection with one strain versus another in those with persistent symptoms.

As the results show, fewer samples were positive for antibody reactivity to OspA by ELISA than were positive for antibodies to p31 by WB. This could be explained by the (i) generally lower limit of detection in WB, (ii) reactivity of PLDS patient antibodies toward an additional protein(s) that has the same migration pattern as OspA (appearing at ∼31 kDa) on WB, and/or (iii) exposure of specific epitopes of the OspA protein in the WB procedure (in which proteins are mostly denatured) but not in ELISA, toward which patients exhibit antibody reactivity. It is worth mentioning that antibody reactivity to the 31-kDa band on WB was also found in some healthy individuals without a history or serologic evidence of Lyme disease. Therefore, the presence of antibodies to the p31 band by itself (i.e., in the absence of antibodies to other B. burgdorferi-specific bands) is unlikely to have biomarker utility in the WB system.

A potential limitation of this study is the fact that EM duration was not taken into account in the comparison between patients and controls, as reliable information was not available for the patient group. While the post-Lyme healthy control subjects were all followed prospectively by one of the investigators (G.P.W.) from the time of diagnosis, the same cannot be said for the PLDS patients, who were recruited as part of a multicenter clinical trial. Thus, it is conceivable that some PLDS patients in the subgroup with EM also presented with objective clinical manifestations of Lyme disease beyond those of EM. Future prospective studies should pay careful attention to EM history and make an attempt to match patients and controls accordingly.

A second limitation of our study may be perceived to be the exclusion of seronegative patients. In this study, we chose to focus specifically on patients and post-Lyme healthy control subjects who were seropositive by whole-cell ELISA. This was done in order to ensure that all samples in the comparison had the minimal detectable antiborrelia antibody response necessary for subsequent analyses. Obviously, our findings and conclusions in this report do not extend to the seronegative subpopulation. It should be noted that in the original clinical trial that provided the specimens examined in this study (16), in which there was simultaneous recruitment of both seropositive and seronegative subjects, nearly 40% of the subjects were, in fact, seronegative. The absence of an antiborrelia antibody response in many PLDS patients points to the heterogeneity of the population under study but does not diminish the significance of the reported findings. Closer examination of the immune response in seronegative PLDS patients, including the antigen specificity of antiborrelia antibodies as a function of time since infection, needs to be done in future prospective studies.

While the observed elevated antibody response to specific borrelial proteins in this study adds to earlier evidence for the existence of a differential immune response in PLDS patients (6) and offers useful clues about the course of the original infection, the data should not be interpreted as having diagnostic value or clinical utility at this point. However, we can conclude that the current data strongly support the continuation of studies aimed at in-depth characterization of the antiborrelia immune response in the affected patient population. It is expected that the expansion of these studies, with the aims to (i) include additional control groups, such as symptom-free individuals with histories of past Lyme arthritis and neurologic Lyme, and (ii) examine the immune response to the entire proteome of the Lyme pathogen, would aid in the development of biomarkers for PLDS and provide important clues to its pathogenesis and potential treatments. This strategy may also prove useful for the study of chronic postinfection symptoms associated with other pathogens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant AI071180-02 to A. Alaedini) and involved the use of specimens derived from an NIH-supported repository (contract number N01-AI-65308). It was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH.

We thank Phillip J. Baker at the National Institutes of Health for his invaluable support and guidance throughout this project. We are grateful to Dianna Chiles-Inguanzo of Euroimmun for assistance in the analysis of the Western blotting data. We thank Diane Holmgren, Donna McKenna, and Susan Bittker for their assistance with specimen collection and organization. We also thank all of the research participants involved in this project.

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aguero-Rosenfeld M. E., Wang G., Schwartz I., Wormser G. P. 2005. Diagnosis of lyme borreliosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:484–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akin E., McHugh G. L., Flavell R. A., Fikrig E., Steere A. C. 1999. The immunoglobulin (IgG) antibody response to OspA and OspB correlates with severe and prolonged Lyme arthritis and the IgG response to P35 correlates with mild and brief arthritis. Infect. Immun. 67:173–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bockenstedt L. K., Mao J., Hodzic E., Barthold S. W., Fish D. 2002. Detection of attenuated, noninfectious spirochetes in Borrelia burgdorferi-infected mice after antibiotic treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 186:1430–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bratton R. L., Whiteside J. W., Hovan M. J., Engle R. L., Edwards F. D. 2008. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 83:566–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. CDC 1995. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 44:590–591 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chandra A., et al. 2010. Anti-neural antibody reactivity in patients with a history of Lyme borreliosis and persistent symptoms. Brain Behav. Immun. 6:1018–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crowley H., Huber B. T. 2003. Host-adapted Borrelia burgdorferi in mice expresses OspA during inflammation. Infect. Immun. 71:4003–4010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Das S., et al. 1996. Characterization of a 30-kDa Borrelia burgdorferi substrate-binding protein homologue. Res. Microbiol. 147:739–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dressler F., Whalen J. A., Reinhardt B. N., Steere A. C. 1993. Western blotting in the serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. J. Infect. Dis. 167:392–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fallon B. A., et al. 2008. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of repeated IV antibiotic therapy for Lyme encephalopathy. Neurology 70:992–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feder H. M., Jr., et al. 2007. A critical appraisal of “chronic Lyme disease.” N. Engl. J. Med. 357:1422–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Halperin J. J. 2008. Nervous system Lyme disease. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 22:261–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hodzic E., Feng S., Holden K., Freet K. J., Barthold S. W. 2008. Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi following antibiotic treatment in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1728–1736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalish R. A., Leong J. M., Steere A. C. 1993. Association of treatment-resistant chronic Lyme arthritis with HLA-DR4 and antibody reactivity to OspA and OspB of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 61:2774–2779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kalish R. A., Leong J. M., Steere A. C. 1995. Early and late antibody responses to full-length and truncated constructs of outer surface protein A of Borrelia burgdorferi in Lyme disease. Infect. Immun. 63:2228–2235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klempner M. S., et al. 2001. Two controlled trials of antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms and a history of Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krupp L. B., et al. 2003. Study and treatment of post Lyme disease (STOP-LD): a randomized double masked clinical trial. Neurology 60:1923–1930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lin T., Oliver J. H., Jr., Gao L., Kollars T. M., Jr., Clark K. L. 2001. Genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in the southern United States based on restriction fragment length polymorphism and sequence analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2500–2507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ma B., Christen B., Leung D., Vigo-Pelfrey C. 1992. Serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis by Western immunoblot: reactivity of various significant antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:370–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marques A. 2008. Chronic Lyme disease: a review. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 22:341–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marques A. R. 2010. Lyme disease: a review. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 10:13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nowalk A. J., Gilmore R. D., Jr., Carroll J. A. 2006. Serologic proteome analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi membrane-associated proteins. Infect. Immun. 74:3864–3873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stanek G., Strle F. 2003. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet 362:1639–1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Steere A. C. 2001. Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steere A. C., Coburn J., Glickstein L. 2004. The emergence of Lyme disease. J. Clin. Invest. 113:1093–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Straubinger R. K. 2000. PCR-based quantification of Borrelia burgdorferi organisms in canine tissues over a 500-day postinfection period. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2191–2199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Straubinger R. K., Summers B. A., Chang Y. F., Appel M. J. 1997. Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi in experimentally infected dogs after antibiotic treatment. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:111–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wormser G. P., et al. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi genotype predicts the capacity for hematogenous dissemination during early Lyme disease. J. Infect. Dis. 198:1358–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wormser G. P., et al. 2006. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:1089–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wormser G. P., et al. 2008. Effect of Borrelia burgdorferi genotype on the sensitivity of C6 and 2-tier testing in North American patients with culture-confirmed Lyme disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47:910–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wormser G. P., et al. 1999. Association of specific subtypes of Borrelia burgdorferi with hematogenous dissemination in early Lyme disease. J. Infect. Dis. 180:720–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]