Abstract

Family–work conflict (FWC) and work–family conflict (WFC) are more likely to exert negative influences in the family domain, resulting in lower life satisfaction and greater internal conflict within the family. Studies have identified several variables that influence the level of WFC and FWC. Variables such as the size of family, the age of children, the work hours and the level of social support impact the experience of WFC and FWC. However, these variables have been conceptualized as antecedents of WFC and FWC; it is also important to consider the consequences these variables have on psychological distress and wellbeing of the working women.

Aim:

to study various factors which could lead to WFC and FWC among married women employees.

Materials and Methods:

The sample consisted of a total of 90 married working women of age between 20 and 50 years. WFC and FWC Scale was administered to measure WFC and FWC of working women. The obtained data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Carl Pearson's Correlation was used to find the relationship between the different variables.

Findings and Conclusion:

The findings of the study emphasized the need to formulate guidelines for the management of WFCs at organizational level as it is related to job satisfaction and performance of the employees.

Keywords: Married, women, work-life balance, employed

INTRODUCTION

Indian families are undergoing rapid changes due to the increased pace of urbanization and modernization. Indian women belonging to all classes have entered into paid occupations. At the present time, Indian women's exposure to educational opportunities is substantially higher than it was some decades ago, especially in the urban setting. This has opened new vistas, increased awareness and raised aspirations of personal growth. This, along with economic pressure, has been instrumental in influencing women's decision to enter the work force. Most studies of employed married women in India have reported economic need as being the primary reason given for working.[1,2]

Women's employment outside the home generally has a positive rather than negative effect on marriage. Campbell et al.[3] studied the effects of family life on women's job performance and work attitudes. The result revealed that women with children were significantly lower in occupational commitment relative to women without children; contrary to expectation, women with younger children outperformed women with older children. Makowska[4] studied psychosocial determinants of stress and well-being among working women. The significance of the work-related stressors was evidently greater than that of the stressors associated with the family function, although the relationship between family functioning, stress and well-being was also significant.

Multiple roles and professional women

Super[5] identified six common life roles. He indicated that the need to balance these different roles simultaneously is a reality for most individuals at various stages throughout their lives. Rather than following a transitional sequence from one role to another, women are required to perform an accumulation of disparate roles simultaneously, each one with its unique pressures.[6] Multiple role-playing has been found to have both positive and negative effects on the mental health and well-being of professional women. In certain instances, women with multiple roles reported better physical and psychological health than women with less role involvement. In other words, they cherished motivational stimulation, self-esteem, a sense of control, physical stamina, and bursts of energy.[7] However, multiple roles have also been found to cause a variety of adverse effects on women's mental and physical health, including loss of appetite, insomnia, overindulgence, and back pains.[8]

Work–life balance

An increasing number of articles have promoted the importance of work–life balance. This highlights the current concern within society and organizations about the impact of multiple roles on the health and well-being of professional women and its implications regarding work and family performance, and women's role in society. The following variables influencing the experience of work–life balance were identified while reviewing the international literature.

Role strain experienced because of multiple roles, i.e., role conflict and role overload[12,13]

Organization culture and work dynamics: Organizational values supporting work–life balance have positive work and personal well-being consequences[14,15]

Personal resources and social support: Several studies confirmed the positive relationship between personalities, emotional support and well-being[16–18]

Career orientation and career stage in which women careers need to be viewed in the context of their life course and time lines[19,20]

Coping and coping strategies: Women use both emotional and problem-focused coping strategies to deal with role conflict.[21]

Work–family conflict and family–work conflict

Work–life balance is the maintenance of a balance between responsibilities at work and at home. Work and family have increasingly become antagonist spheres, equally greedy of energy and time and responsible for work–family conflict (WFC).[22] These conflicts are intensified by the “cultural contradictions of motherhood”, as women are increasingly encouraged to seek self-fulfillment in demanding careers, they also face intensified pressures to sacrifice themselves for their children by providing “intensive parenting”, highly involved childrearing and development.[23] Additional problems faced by employed women are those associated with finding adequate, affordable access to child and elderly care.[24,25]

WFC has been defined as a type of inter-role conflict wherein some responsibilities from the work and family domains are not compatible and have a negative influence on an employee's work situation.[12] Its theoretical background is a scarcity hypothesis which describes those individuals in certain, limited amount of energy. These roles tend to drain them and cause stress or inter-role conflict.[26–28] Results of previous research indicate that WFC is related to a number of negative job attitudes and consequences including lower overall job satisfaction[29] and greater propensity to leave a position.[30]

Family–work conflict (FWC) is also a type of inter-role conflict in which family and work responsibilities are not compatible.[12] Previous research suggests that FWC is more likely to exert its negative influences in the home domain, resulting in lower life satisfaction and greater internal conflict within the family unit. However, FWC is related to attitudes about the job or workplace.[31] Both WFC and FWC basically result from an individual trying to meet an overabundance of conflicting demands from the different domains in which women are operating.

Workplace characteristics can also contribute to higher levels of WFC. Researchers have found that the number of hours worked per week, the amount and frequency of overtime required, an inflexible work schedule, unsupportive supervisor, and an inhospitable organizational culture increase the likelihood that women employees will experience conflict between their work and family role.[12,32,33] Baruch and Barnett[34] found that women who had multiple life roles (e.g., mother, wife, employee) were less depressed and had higher self-esteem than women who were more satisfied in their marriages and jobs compared to women and men who were not married, unemployed, or childless. However, authors argued quality of role rather than the quantity of roles that matters. That is, there is a positive association between multiple roles and good mental health when a woman likes her job and likes her home life.

WFC and FWC are generally considered distinct but related constructs. Research to date has primarily investigated how work interferes or conflicts with family. From work–family and family–work perspectives, this type of conflict reflects the degree to which role responsibilities from the work and family domains are incompatible. That is “participation in the work (family) role is made more difficult by virtue of participation in the family (work) role”.[12]

Frone et al.[35] suggested that WFC and FWC are related through a bi-directional nature where one can affect the other. The work domain variables such as work stress may cause work roles to interfere with family roles; the level of conflict in the family domain impacts work activities, causing more work conflict, thus creating a vicious cycle. Therefore, work domain variables that relate to WFC indirectly affect FWC through the bi-directional relationship between each construct. Family responsibility might be related to WFC when the employee experiences a very high work overload that impacts the employee's ability to perform even minor family-related roles. Such a situation likely affects WFC through the bi-directional nature of the two constructs. While no researchers have considered the relationship between these constructs in a full measurement model, Carlson and Kacmar[36] used structural model and found positive and significant paths between WFC and FWC.

Work stress: Its relation with WFC and FWC

Work stress is usually conceptualized as work-role conflict, work-role overload, and work-role ambiguity[37,38] (House et al., 1983). Each has the potential to affect WFC.[39] With respect to work-role conflict, the more conflict among work roles, the greater the chances that stress will spill over and cause negative behaviors that interfere with fulfilling family roles.[40] Role overload is the result of having too many things to do in a given time period.[39] As time is constrained by having too many tasks to accomplish at work, the employee may need to use time allocated to the family role which could cause WFC.[12] Work-role ambiguity occurs when workers are unsure of what is expected of them in a work role. As uncertainty concerning work roles increase, employees use more mental energy to decipher it. This requirement may drain mental energy and attention needed for their family roles. Carlson and Kacmar[36] found that role overload and role conflict were predictors of WFC, yet did not find significant results for role ambiguity.

Kandel et al.[41] studied the nature of specific strains and stresses among married women in their marital, occupational and house work roles. They found that strains and stresses are lower in family roles than in occupational and household roles among the married women. These have more severe consequences for the psychological well-being of women than occupational strains and stresses. Strains predicted distress through role-specific stress, with strains deriving from contribution of role-specific stress. Chassin et al.[42] found three types of conflicts in their study research on a sample of 83 dual worker couples with pre-school children. These are: (1) conflicts between demands of multiple roles, (2) conflict between role expectations of self and spouse, and (3) lack of congruence between expectation and reality of roles. The authors felt that self-role congruence in women leads to better mental health.

Research studies have identified several variables that influence the level of WFC and FWC. Variables such as the size of family, the age of children, the number of hours worked outside the home, the level of control one has over one's work hours, flexible or inflexible work hours and the level of social support impact the experience of WFC and FWC. However, these variables have been conceptualized as antecedents of WFC and FWC; it is also important to consider the consequences these variables have on psychological distress and well-being of the working women. Most of these studies revived are in western context; there is a scarcity of research in this area in the Indian context. Hence, the researchers made an attempt to study various factors which could lead to WFC and FWC among married women employees.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The sample consisted of a total of 90 married working women of age between 20 and 50 years. Thirty married working women were selected using simple random sampling technique from each setting, i.e., industrial setting, school setting and hospital setting. The women who were married at least for 3 years, living with spouse and engaged in work for at least 1 year were included in the study. The women with psychiatric and neurological illness with spouse suffering from physical or psychiatric and neurological illness were excluded from the study. The obtained data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Carl Pearson's Correlation was used to find the relationship between the different variables.

Instruments

WFC and FWC Scale by Netemeyer et al.[31]: The WFC and FWC Scale is a 10-item, 7-point Likert scale, which measures WFC and FWC of working individuals. The participants are asked to indicate the extent to which they agree with each item. The responses range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate high level of work/family conflict, while lower scores indicate low levels of work/family conflict. The coefficient alpha of the scale ranged from 0.82 to 0.90. The scale was found to have good content, construct and predictive validity.

RESULTS

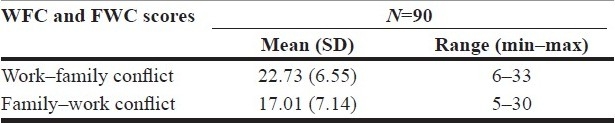

The mean age of the respondent was 38.70 (SD 8.66) years. Nearly half (44.4%) of the women employees were aged between 41 and 50 years; majority (83.3%) were Hindus from urban background (72%). With regard to number of children, 41.1% of the women had one child showing trend in small family system and 26.7% had two children. Nearly 70% of the women were working to support their families, 20% of the respondents were working because they were career oriented, and 10% were working to fulfill their personal financial needs. The mean scores of WFC and FWC among the women [Table 1] show that the women scored highest in WFC (Mean 22.73; SD=6.55) and lowest in FWC (Mean 17.01; SD=7.14).

Table 1.

Scores of women on work–family conflict and family–work conflict

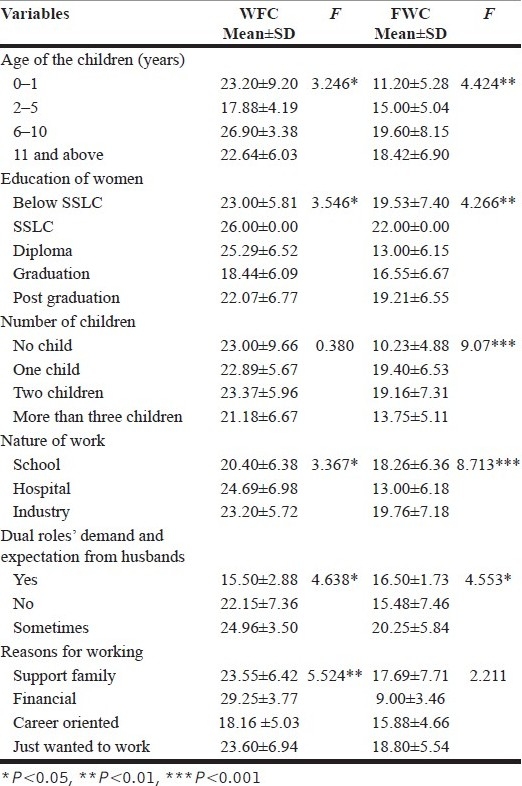

The result of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) [Table 2] on the ratings of WFC and FWC across the different categories of the women showed significant (F=3.246; P<0.05) WFC and FWC (F=5.424; P<0.01) among the women whose eldest child was in the age group of 6–10 years. Similarly, women belonging to different educational attainment, especially SSLC background, differently rated their WFC (F=3.456; P<0.05) and FWC (F=4.226; P<0.01). Further, high FWC was found among those who were having one child, whereas less FWC was found among those not having children. However, the rating among different groups on FWC was statistically significant (F=9.07; P<0.001). There were significant variations in the group means of women working in different settings on WFC (F=3.376; P<0.05) and FWC (F=8.713; P<0.001). The women working in hospital setting reported higher WFC compared to those working at school or industry setting. FWC was more among the women working in industry, when compared to those working in school and hospital setting. FWC (F=4.638; P<0.05) and WFC (F=3.553; P<0.05) were significantly high among the women whose husbands demanded dual roles from working women. The women working due to financial needs scored significantly high WFC (F=5.254; P<0.01) in comparison with the other groups.

Table 2.

One-way ANOVA – Background variables and work–family conflict and family–work conflict

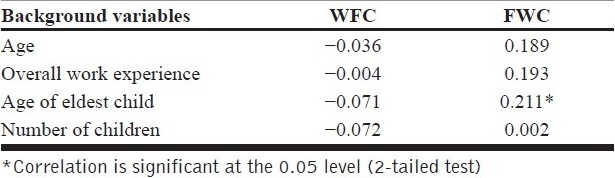

The results [Table 3] also indicate that age of the children was positively correlated (P<0.05) with FWC of the working women. However, non-significant relationships were found between age of the women, overall work experience, and number of children on WFC and FWC. In addition, non-significant relationship was also found between the age of the eldest child and WFC.

Table 3.

Intercorrelation among the work–family conflict and family–work conflict with background variables

DISCUSSION

The present study was aimed at exploring the factors which lead to WFC and FWC among married women employees working in different settings. WFC and FWC were found to be more among the women having the eldest child between 6 and 10 years. Moreover, the age of the children was significantly positively correlated with FWC among the working women. The findings of the study support the earlier studies that age of the children is related to more WFC and FWC among married women employees. Chassin et al.[42] found that women with pre-school children experience different types of conflicts and concluded that self-role congruence in women leads to better mental health. Some researchers used parental overload[33] which included number of children; others used variables such as family demand[43] in predicting WFC. Higgins et al.[44] found that family involvement and family expectations were related to conflict in the family, but not related to WFC. High levels of family responsibility cause increased time requirements and strain on the family, thereby interfering with the employee's work roles.[45] As children and elderly family members require additional care, the obligation to meet their needs can influence family roles, which can create inter-role conflict[46] and impact family roles,[47] producing FWC.[45] Studies also reported that women having younger children experience more role conflicts.[48,49]

Workplace characteristics also contribute to higher levels of WFC. In the present study, women working in hospital setting reported more WFC, whereas FWC was found to be more among those women working in industrial setting. Researchers have found that the number of hours worked per week, the amount and frequency of overtime, an inflexible work schedule, unsupportive supervisor, and an inhospitable organizational culture for balancing work and family increase the likelihood of women employees to experience conflict between their work and family roles.[32,33,50]

Dual role demands and expectation from working women by husbands was significantly related to high WFC and FWC among the working women in the present study. According to Sharma,[17] the support and involvement of husband postively relates to lower levels of role conflict experienced by the married working women. Carlson et al.[11] found that experience of work demands negatively influenced family responsiblilites in more instances than family demands that influenced work responisibilites. Job-parent conflict was reported to be the most often experienced conflict among the women.

Survey in West showed that young women are expected to combine a career with motherhood.[51,52] In Indian context, a lot of women, especially those from the lower middle class, are seeking the job market today because they have to augment the family income. They have to provide a better life for their families, pay their children's tuition fees and plan a better future for them. In the present study, it is seen that the women working due to financial needs reported higher WFC when compared to those working for other reasons. Schular[53] found that the financial need is the chief reported reason for women taking up employment. Phillips and Imholff[54] argue that many women take up job on compulsion, but it is the career which is extremely gratifying. In the present study, it is noted that only a few women had taken up employment for career. Sharma[55] reported that problems can arise if woman works for money. In that case, woman needs to be careful not to bring home her frustration and unhappiness, which can affect family relationships.

Future directions

It is critical for work and family research to fully understand the conditions under which the married women employees experience conflict between their roles. There is a need to consider working environment, job satisfaction, family support and number of working hours in the future research. Future studies should also continue to refine the methodology used in the area of work–family research. In order to attain in-depth understanding of one's work and family life, researchers who study work–family roles should include multiple perspectives such as job stress, quality of life, mental health, and work demands. In addition, it is necessary to explore multiple waves of data collection over a longer period of time to better understand the changing nature of work family roles over time. Longitudinal studies need to be conducted to examine how the stages of life (e.g., marriage, child birth, and child rearing) affect work and family concerns. It is clear from the current study that married women employees indeed experience WFC while attempting to balance their work and family lives. Thus, organizations need to formulate guidelines for the management of WFCs since they are related to job satisfaction and performance of the employees.

Like all studies, the current research has limitations. The sample in the present study is quite small; hence, the generalization of the findings is limited. Additional research is needed in other employment settings to explore the relationship between WFC and quality of life among married women employees.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Srivastava V. New Delhi: National Publishing House; 1978. Employment of educated women in India; its causes and consequences. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramanna A, Bombawale U. Transitory status images of working women in modern India. Indian J Soc Work. 1984;45:189–202. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell DJ, Campbell KM, Kennard D. The effects of family responsibilities on the work commitment and job performance of non professional women. J Occupa Organ Psych. 1994;67:283–96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maskowska Z. Psychosocial characteristics of work and family as a determinant of stress and well-being of women: A preliminary study. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 1995;8:215–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Super DE. A life-span, life-space approach to career development. J Vocat Behar. 1980;16:282–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopp RG, Ruzicka FM. Women's multiple roles and psychological well-being. Psychol Rep. 1993;72:1351–4. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3c.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doress-Wortes PB. Adding elder care to women's multiples roles: A critical review of the caregiver stress and multiple roles literature. Sex Roles. 1994;31:597–613. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes DL, Glinsky E. Gender, job and family conditions and psychological symptoms. Psychol Women Quart. 1994;18:251–70. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Facione NC. Role overload and health: The married on the wages labor force. Health Care Women Int. 1992;15:157–67. doi: 10.1080/07399339409516107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adelman PK. Multiple roles and health among older adults. Res Aging. 1994;16:142–66. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson DS, Kacmar KM, Williams LJ. Paper Presented at 1998 Academic Management Meeting. California: 1998. The development and validation of a multi-dimensional measure of work–family conflict. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manage Rev. 1985;10:76–88. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu CK, Shaffer MA. The tug of work and family. Personnel Rev. 2001;30:502–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stover DL. The horizontal distribution of female managers within organization. Work Occup. 1994;1:385–402. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burke RJ. Organizationa values, work experices and satisfactions among managerial and professional women. J Mangament Dev. 2001;20:346–54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amatea ES, Fong ML. The impact of roles stressors and peronal resoucnes on the stress experience of professional women. Psychol Women Q. 1991;15:419–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma S. Multiple role and women's health: A multi-linear model. Equal Oppor Int. 1999;18:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill S, Davidson MJ. Problems and pressures facing lone mothers in managment and professional occupations - A pilot study. Women Manag Rev. 2000;17:383–99. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rapoport R, Rapoport RN. New York: Praeger Publishing; 1980. Work, family and the carrer. [Google Scholar]

- 20.White B. The career development of sucessful women. Women Manage Rev. 1995;10:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. New York: Springer Publishing; 1984. Stress, appraisal and coping. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coser LA. New York: The Free Press; 1974. Greedy institutions: Patterns of undivided commitment. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hays S. New York: Yale University Press; 1996. The cultural contradictions of motherhood. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reskin B, Ross CE. Jobs, authority, and earnings among managers: The continuing significance of sex. Work Occup. 1992;19:342–65. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reskin B, Padavic I. Thousand Oaks: Pine Gorge Press; 1994. Women and Men at Work. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marks S. Multiple roles and role strain: Some notes and human energy, time, and commitment. Am Sociol Rev. 1977;42:921–36. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aryee S. Antecedents and outcomes of work family conflict among married professional women: Evidence from Singapore. Hum Relat. 1992;45:813–37. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grandey AA, Cropanzano R. The conservation of resources model applied to work family conflict and strain. J Voc Behar. 1999;54:350–70. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boles JS, Babin BJ. On the front lines: Stress, conflict, and the customer service provider. J Bus Res. 1996;37:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Good LK, Grovalynn FS, James WG. Antecedents of turnover intentions among retail management personnel. J Retailing. 1988;64:295–314. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Netemeyer RG, Boles JS, McMurrian R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81:400–10. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galinsky E, Bond JT, Friedman DE. The role of employers in addressing the needs of employed parents. J Socl Issues. 1996;52:111–36. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frone MR, Yardley JK, Markel KS. Developing and testing an integrative model of the work–family interface. J Vocat Behav. 1997b;50:145–67. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baruch GK, Barnett RC. Role quality, multiple role involvement, and psychological well-being in midlife women. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;51:578–85. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Antecedents and outcomes of work–family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. J Appl Psychol. 1992;77:65–78. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carlson DS, Kacmar KM. Work-family conflict in the organization: Do life role values make a difference? J Manag. 2000;26:1031–54. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rizzo JR, House RJ, Lirtzman SI. Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Adm Sci Q. 1970;15:119–28. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooke RA, Rousseau DM. Stress and strain from family roles and work-roles expectations. J Appl Psychol. 1984;69:252–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bachrach SB, Bamberger P, Conley S. Work-home conflict among nurses and engineers: Mediating and impact of role stress on burnout and satisfaction at work K. Organ Behar. 1991;12:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenhaus JH, Bedian AG, Mossholder KW. Work experiences, job performance, and feelings of personal and family well-being. J Voc Behar. 1987;31:200–15. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kandel DB, Davies M, Revies HV. The stressfulness of daily social roles for women.Marital, occupational and household roles. J Health Soc Behav. 1985;26:64–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chassin L, Zeirs A, Cooper KR. Role perceptions self role congruence and marital satisfaction in dual worker couples with preschool children. Soc Psychol Quat. 1985;48:301–11. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang N, Chen CC, Choi J, Zou Y. Sources of work-family conflict: A Sino-U.S. comparison of the effects of work and family demands. Acad Manage J. 2000;43:113–23. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higgins CA, Duxbury LE, Irving RH. Work-family conflict in the dual-career family. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1992;51:51–75. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boise L, Neal MB. Family responsibilities and absenteeism: Employees caring for parents versus employees caring for children. J Managerial Issues. 1996;2:218–38. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan RL, Wolfe DM, Quinn R, Snoek JD, Rosenthai RA. New York: Weley; 1964. Organizational stress. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piotrkowski CS, Rapoport RN, Rapoport R. Families and work. In: Sussman M, Steinmetz S, editors. Handbook of marriage and the family. New York, NY: Plenum; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buetell NJ, Greeehaus JH. Paper presented at The Annual Meeting of The Academy of Management. California: 1980. Some sources and consequences of inter-role conflict among married women. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bedeian AG, Burke BG, Moffett RG. Outcomes of work–family conflict among married male and female professionals. J Manag. 1998;14:475–91. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas LT, Ganster DL. Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: A control perspective. J Appl Psychol. 1995;80:6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dave H. Young women expected and preferred patterns of employment and child care. Sex Roles. 1998;35:98–102. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoffnung M. Motherhood: Contemporary conflict for women. In: Freeman J, editor. Women: A feminist perspective. 2nd ed. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield; 1995. pp. 162–81. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schular C. Women and work: Psychological effects of occupational contexts. Am J Sociol. 1978;85:66–94. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Phillips SD, Imholff AR. Women and career development: A decade of research. Annal Revw Psychol. 1977;45:31–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma U. New Delhi: Mittal Publishers; 2006. Female labour in India. [Google Scholar]