Abstract

Borrelia burgdorferi OspC is an outer membrane lipoprotein required for the establishment of infection in mammals. Due to its universal distribution among B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains and high antigenicity, it is being explored for the development of a next-generation Lyme disease vaccine. An understanding of the surface presentation of OspC will facilitate efforts to maximize its potential as a vaccine candidate. OspC forms homodimers at the cell surface, and it has been hypothesized that it may also form oligomeric arrays. Here, we employ site-directed mutagenesis to test the hypothesis that interdimeric disulfide bonds at cysteine 130 (C130) mediate oligomerization. B. burgdorferi B31 ospC was replaced with a C130A substitution mutant to yield strain B31::ospC(C130A). Recombinant protein was also generated. Disulfide-bond-dependent oligomer formation was demonstrated and determined to be dependent on C130. Oligomerization was not required for in vivo function, as B31::ospC(C130A) retained infectivity and disseminated normally. The total IgG response and the induced isotype pattern were similar between mice infected with untransformed B31 and those infected with the B31::ospC(C130A) strain. These data indicate that the immune response to OspC is not significantly altered by formation of OspC oligomers, a finding that has significant implications in Lyme disease vaccine design.

INTRODUCTION

Lyme borreliosis is an emerging infectious disease in North America and Europe caused by the spirochetes Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia garinii, and Borrelia afzelii (2, 3, 9, 21, 25, 31). B. burgdorferi is maintained in an enzootic cycle involving Ixodes ticks and reservoir mammals and birds (4, 5, 18). As the spirochetes transit between ticks and reservoir hosts, differential gene expression aids in adaptation to the radically different environments. OspC, a 21-kDa plasmid-encoded lipoprotein, is upregulated in ticks concurrent with the blood meal and is expressed at a high level during the first weeks of infection in mammals (6, 17, 19, 32, 40, 42, 43). OspC is required to establish infection but not for persistence (20, 46–49). The function of OspC has not yet been clearly defined (37). It has been hypothesized that ligand binding domain 1 (LBD1) of OspC binds a small ligand and that this interaction is required for the establishment of infection in mammals (13). OspC also binds other ligands, including Salp15 (a tick-derived protein with immunomodulatory activity) and plasminogen, by unknown mechanisms (1, 10, 22, 23, 29, 38).

OspC is predominantly helical and forms a homodimer tethered to the outer membrane by an N-terminal tripalmitoyl-S-glyceryl-cysteine moiety (8, 11, 16, 17, 24, 27, 52). Residues lining the dimeric interface are conserved, while the remainder of OspC is variable in sequence. More than 30 phylogenetically distinct types of OspC have been defined (4, 11, 51). It has been hypothesized that OspC and its relapsing fever Borrelia ortholog (Vsp) form arrays in the outer membrane (30, 52).

OspC is a candidate for a next-generation Lyme disease vaccine (11, 12, 15, 28). The surface presentation of OspC may have implications for vaccine design. Array formation can influence the exposure of epitopes and induce T-cell-independent humoral immune responses (50). Here, we test the hypothesis that cysteine 130 (C130), forms an interdimeric disulfide bond that mediates the formation of higher-order oligomers or arrays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site-directed mutagenesis and production of r-OspC and anti-OspC antiserum.

Recombinant OspC (r-OspC) was produced by amplification of ospC (lacking the signal sequence and the lipidated cysteine) from wild-type (wt) B. burgdorferi strain B31 (type A OspC). A cysteine-to-alanine mutation at amino acid 130 (C130A) was accomplished by overlap extension/amplification PCR using mutagenic primers (5′-GCGGCTAAGAAAGCTTCTGAAAC-3′ and its reverse complement) (12). Wild-type and C130A-mutated ospC genes were annealed to the pET46 Ek/LIC vector (Novagen), transformed into Novablue Escherichia coli (14), and confirmed by DNA sequencing (MWG Biotech). Recombinant proteins were expressed from E. coli BL21(DE3) cells and purified by nickel affinity chromatography (14). Anti-OspC antiserum was generated by immunization of C3H/HeJ mice with r-OspC(wt) adsorbed to alum (Imject, Pierce) by established protocols (13). Far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectra of r-OspC(wt) and r-OspC(C130A) proteins were measured at 20°C in a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Easton, MD) as previously described (13). Three independent scans were made of each protein.

Allelic exchange replacement of wild-type ospC.

A pCAEV1 allelic exchange vector was created which contained the ospC(C130A) gene (13). ospC(C130A) was amplified with 5′ and 3′ BspEI restriction sites, digested, and ligated into the BspEI-digested, dephosphorylated (CIP) pCAEV1 vector. The plasmid was propagated in Novablue E. coli and purified (Qiagen), and the insert was sequenced (MWG Biotech). B. burgdorferi B31 clone 5A4 (35) was transformed as previously described (13), with selection by streptomycin. Clonal cultures of the resultant B31::ospC(C130A) strain were generated by subsurface plating, with plasmid content assessed by PCR using plasmid-specific primer sets (39). The correct allelic exchange sequence was confirmed as previously described (13). Untransformed wild-type cells (B31), an ospC deletion mutant (B31ΔospC), and an allelic exchanged strain carrying the wild-type ospC gene [B31::ospC(wt)] served as controls (13). Growth rates were determined by daily triplicate cell counts of cultures grown at 37°C in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly (BSK) medium (no antibiotics).

Proteinase K digestion and immunofluorescence assays.

The presentation of OspC at the Borrelia cell surface was assessed by immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) assay and treatment of intact cells with proteinase K. Cells were transferred from 33°C to 37°C (and maintained for 2 days) to upregulate OspC production. Surface exposure of proteins was assessed by proteinase K digestion and Western blotting as previously described, with periplasmic FlaB protein serving as a control (13). To assess the distribution of OspC at the cell surface, immobilized cells were probed with anti-OspC antiserum (1:2,000) and Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200) (13). Slides were mounted with Prolong Gold (Invitrogen), and the cells were visualized using an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope.

Analysis of disulfide-bond-mediated oligomerization.

Interdimeric disulfide bond formation was assessed in r-OspC(wt) and r-OspC(C130A), and in OspC expressed by the B31, B31::ospC(wt), and B31::ospC(C130A) strains, with B31ΔospC as a negative control. All Borrelia strains were transferred to 37°C for 2 days prior to harvesting to upregulate OspC expression (6, 45). The cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), suspended to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.002 μl−1 in reducing (β-mercaptoethanol) or nonreducing SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and incubated at 100°C for 10 min. r-OspC (30 ng) and 2 μl of each cell lysate were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with anti-OspC antiserum (1:2,000) and goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP, 1:40,000).

Analysis of the oligomeric state of r-OspC.

The oligomeric state of OspC was assessed by blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE), using a modification of the technique developed by Schägger et al. (41). Fifty nanograms of r-OspC(wt) or r-OspC(C130A) was diluted in BN-PAGE sample buffer (50 mM Bis-Tris [pH 7.0], 15% glycerol, 0.02% Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 [CBB-G250]) with or without β-mercaptoethanol and separated on a Bis-Tris acrylamide gel (4 to 16% Native-PAGE; Invitrogen) using 50 mM Bis-Tris (pH 7) and 50 mM Tricine-15 mM Bis-Tris (pH 7) as anode and cathode buffers, respectively. The gel was run under cooled conditions (100 V for 20 min followed by 200 V for 40 min) with cathode buffer containing 0.002% CBB-G250. The gel was then run at 200 V for an additional 40 min with cathode buffer with no dye. Following electrophoresis, the gel was electroblotted to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF), and the blot was probed with anti-OspC antiserum and goat-anti-mouse IgG-HRP. Molecular masses of the OspC bands were estimated by interpolation from a standard curve generated with NativeMark (Invitrogen) and bovine and chicken egg albumin.

Assessment of plasminogen binding by wild-type and site-directed mutant proteins.

Plasminogen binding by recombinant OspC was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (29). ELISA plates (Costar 3590) were coated with plasminogen (P7999; 500 ng well−1 [Sigma]) in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6). The wells were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS-Tween (PBS-T). r-OspC proteins (1 μg well−1 in blocking buffer) were incubated in triplicate wells for 2 h at room temperature. Bound OspC was detected by mouse anti-His tag monoclonal antibody (MAb, 1:1,000; Pierce) and then by goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP. Binding was quantified with ABTS [2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid)] chromogen.

Mouse infection.

To assess infectivity and dissemination, mice (two trials of five C3H/HeJ mice per group) were needle inoculated with 104 cells of B31, B31::ospC(wt), B31::ospC(C130A), or B31ΔospC. After 4 weeks, the mice were bled by tail nick and euthanized, and tissues were collected from the ear and bladder (five mice) or the ear, bladder, brain, heart, tibiotarsal joint, and kidney (five mice). Tissues were placed in BSK medium supplemented with rifampin, fosfomycin, and amphotericin B. The IgG response was determined in all mice by ELISA, with immobilized whole B. burgdorferi cells or r-OspC serving as the capture antigen, using standard methods as previously described (13). Potential differences in induced antibody isotypes were assessed by ELISA. ELISA plates were coated with r-OspC(wt) at 200 ng well−1, blocked with 1% BSA in PBS-T, and then probed with a 1:100 dilution of sera from mice infected with B31 or B31::ospC(C130A) strains. Secondary detection was by mouse isotype-specific goat antisera (Sigma) and rabbit anti-goat IgG-HRP.

RESULTS

Production of C130A mutant r-OspC and analysis of protein secondary structure.

Full-length native OspC harbors two Cys residues: an N-terminal tripalmitoyl glyceryl-modified Cys and C130. r-OspC was generated that lacked the leader sequence and the N-terminal Cys residue. In the native protein, the modification of the N-terminal Cys prevents it from playing a role in disulfide-bond-mediated oligomerization. To determine if C130 is involved in OspC oligomerization, recombinant protein harboring a C130A substitution, r-OspC(C130A), was generated. Circular dichroism revealed alpha-helical contents of 56% ± 4% and 57.5% ± 4% for r-OspC(C130A) and r- OspC(wt), respectively.

Allelic exchange of the ospC gene and analysis of the resulting strains.

To determine if OspC dimers form disulfide bonds that mediate higher-order oligomerization in vivo, B. burgdorferi B31 ospC was replaced with ospC(C130A) by allelic exchange. Control strains included B31::ospC(wt) (a wild-type ospC gene replaced with a wild-type ospC gene flanked by a resistance cassette) and B31ΔospC (ospC deletion mutant) (13). The B31::ospC(C130A) and B31ΔospC strains contain all parental plasmids, while the B31::ospC(wt) strain lacks lp21 (13). Loss of lp21 is inconsequential as it is not required for infectivity (35). The production of OspC(C130A) and the expression of antibiotic resistance by B. burgdorferi B31 did not affect growth rate (data not shown). While immunoblot analyses of the in vitro-cultivated strains suggest minor differences in OspC expression, the resulting anti-OspC titers in mice were similar (discussed below). It is important to note that only a subset of cells produce OspC during cultivation (44). Hence, the expression differences among cultivated strains are most likely a reflection of this phenomenon.

Analysis of OspC production and surface presentation.

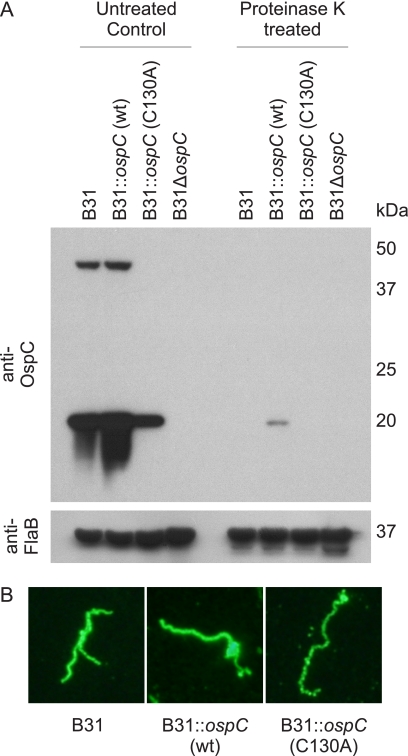

OspC production in all strains (except B31ΔospC) was demonstrated by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1A). To determine if each strain presents OspC at the cell surface in a manner consistent with the parental B31 strain, proteinase K digestion and IFA analyses were performed. Cells were exposed (or not exposed) to proteinase K, and immunoblots of the cell lysates were screened with anti-OspC or anti-FlaB antisera. Exposure to proteinase K resulted in the loss of detection of OspC, but not the periplasmic FlaB (Fig. 1A). IFA demonstrated no visible differences in surface labeling patterns (Fig. 1B). It can be concluded that the C130A substitution does not influence the surface presentation of OspC.

Fig. 1.

Transgenic B. burgdorferi produce OspC and present it at the cell surface. Control or transgenic strains of B. burgdorferi B31 were incubated with or without proteinase K, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF, and screened with anti-OspC or anti-FlaB antiserum (A). Indirect immunofluorescent assays using polyclonal anti-OspC antiserum (B) demonstrate the pattern of OspC surface expression. The methods used are described in the text.

Assessment of oligomerization of OspC in vitro and in vivo.

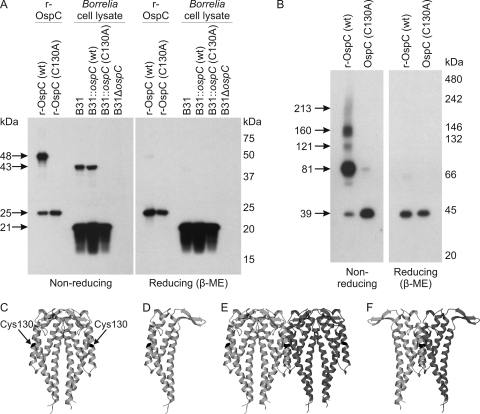

To assess the formation of disulfide bonds, r-OspC proteins and cell lysates of each strain were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing (β-mercaptoethanol) and nonreducing conditions (Fig. 2A). The monomeric native OspC and His-tagged r-OspC proteins have masses of 20.3 kDa and 22 kDa, respectively. Under nonreducing conditions, r-OspC(wt) existed in both monomeric and dimeric forms, while r-OspC(C130A) existed only in monomeric form (Fig. 2A). Under reducing conditions, only monomers were detected (see the conceptual model presented in Fig. 2C to F). Dimeric OspC was also detected in B31 and B31::ospC(wt) cell lysates when separated under nonreducing conditions but not in the B31::ospC(C130A) cell lysate.

Fig. 2.

Formation of disulfide-dependent oligomers by r-OspC and OspC expressed at the Borrelia cell surface. (A) r-OspC(wt) and r-OspC(C130A) (30 ng) and Borrelia cell lysates (strains indicated above figure) were separated by SDS-PAGE under disulfide-reducing (β-mercaptoethanol [β-ME]) or nonreducing conditions, blotted to PVDF, and probed with anti-OspC antiserum. Calculated molecular masses are shown to the left. (B) Western blot of r-OspC(wt) and r-OspC(C130A) (50 ng) separated by blue native PAGE under reducing or nonreducing conditions, blotted to PVDF, and probed with anti-OspC antiserum. Calculated molecular masses are shown to the left. Panels C to F show conceptual models of OspC structures under various electrophoresis conditions. The hydrophobically bound OspC dimer (C) can be maintained under native conditions or separated into component monomers (D) under denaturing conditions. In contrast, an oligomer composed of two or more dimers covalently bound at C130 (E) will dissociate under denaturing conditions into monomers and covalently bound dimers (F), which will dissociate to monomers only under reducing conditions. All models are derived from structure 1GGQ (27).

To determine if r-OspC dimers can oligomerize, r-OspC(wt) and r-OspC(C130A) were separated under nondenaturing (both reducing and nonreducing) conditions using blue native PAGE. Under nonreducing conditions, five immunoreactive bands were detected, all with molecular masses consistent with OspC oligomers from single dimers to chains of five dimers (Fig. 2B). Only dimers maintained by hydrophobic interactions were observed for the C130A protein. Under reducing conditions, all OspC was dimeric (Fig. 2B).

Plasminogen binding by recombinant OspC proteins.

The ability of r-OspC(C130A) to bind plasminogen was assessed in an ELISA format. Consistent with earlier studies, low-level plasminogen binding was observed (13, 29). Only minor differences in plasminogen binding were observed between r- OspC(wt) and r-OspC(C130A) (data not shown). It can be concluded that interdimeric disulfide bond formation is not required for plasminogen binding. It remains to be determined if OspC plasminogen binding is of biological significance.

Infectivity and dissemination of strains expressing wild-type or C130A OspC.

The ability of each strain to establish infection in mice was assessed using needle inoculation in two trials (five mice per group). Four weeks postinoculation, blood was collected and tissue biopsy samples were harvested and placed in medium. Positive cultures were found in all mice, except those infected with the negative control B31ΔospC strain. Cultivation of each infectious strain from mouse tissues did not reveal differences in dissemination patterns among strains (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of culture results from tissues of mice inoculated with B31 and ospC transgenic strains

| Strain | No. of mice with positive culture/no. inoculated |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ear | Bladder | Brain | Heart | Joint | Kidney | |

| B31 (untransformed) | 10/10 | 10/10 | 1/5 | 3/5 | 1/5 | 1/5 |

| B31::ospC(wt) | 10/10 | 9/10 | 0/5 | 5/5 | 3/5 | 0/5 |

| B31::ospC(C130A) | 5/10 | 10/10 | 0/5 | 4/5 | 2/5 | 0/5 |

| B31ΔospC | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

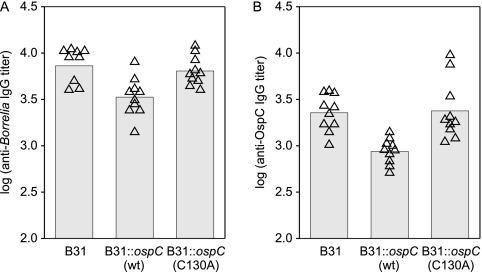

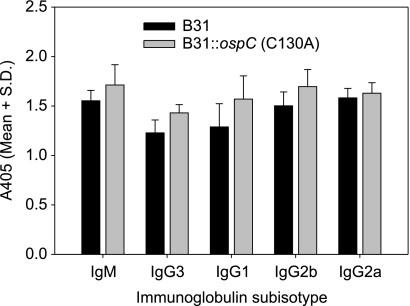

To assess the antibody response elicited by each strain, anti-OspC and anti-B. burgdorferi IgG titers were determined by ELISA using r-OspC or B. burgdorferi whole cells as the immobilized antigen. Whole-cell and OspC-specific IgG titers were similar for mice infected with B31, B31::ospC(wt), and B31::ospC(C130A) cells (Fig. 3). In addition, no significant differences were detected in the OspC-specific isotype profile in mice infected with B31 or B31::ospC(C130A) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of the antibody response to B. burgdorferi B31 and ospC transgenic strains in mice. ELISAs were conducted using serum harvested from mice 4 weeks after needle inoculation (infecting strain indicated along the x axis). The sera were serially diluted, screened against immobilized whole B. burgdorferi B31 cells (A) or r-OspC(wt) (B), and titers (indicated by triangles) were calculated as the inverse dilution corresponding to one-third of the plateau optical density. Geometric mean titers are indicated by the bars.

Fig. 4.

Anti-OspC antibody isotype profile in mice infected with B. burgdorferi B31 or B31::ospC(C130A). ELISAs were conducted using serum harvested from mice 4 weeks after needle inoculation. Antibodies were captured by immobilized r-OspC(wt) and detected by isotype-specific antisera. Columns indicate the mean absorbance, with standard deviations between mice indicated by the error bars.

DISCUSSION

OspC is an important virulence factor for species of the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex and a potential candidate for a next-generation Lyme disease vaccine (12, 14, 15, 20, 34, 46–49). Efforts to define the function of OspC and develop a vaccine have been significantly enhanced by recent analyses of OspC structure-function relationships and its antigenic structure (13, 16, 26, 27, 51). A postulate that has not yet been tested is that OspC may form functionally and immunologically significant arrays in the Borrelia outer membrane (30). While freeze-fracture microscopic analyses indicate the existence of membrane protein arrays in B. burgdorferi, the composition of these arrays have not yet been determined (36). Here we test the hypothesis that hydrophobic based OspC dimers form biologically relevant higher-order oligomers that result from interdimeric disulfide bonding mediated by residue C130. To assess this, a recombinant site-directed OspC mutant protein, r-OspC(C130A), and a B. burgdorferi strain that produces this site-directed mutant, B31::ospC(C130A), were generated and OspC oligomerization tested. Recombinant wild-type OspC formed oligomeric chains of two to five dimers. Formation of these oligomers was eliminated by reducing conditions and proved to be strictly dependent on C130. While technical limitations prevented the direct assessment of OspC oligomeric length at the Borrelia cell surface, the occurrence of disulfide-bonded OspC at the cell surface and the data obtained with recombinant proteins support the notion that disulfide-dependent oligomers form in vivo.

Direct functional assays for OspC have not yet been defined. However, due to the essential nature of OspC, mutations that perturb critical determinants of the protein can be identified by assessing infectivity in mice. To determine if OspC oligomerization is required for OspC to carry out its in vivo function, wild-type and B31::ospC(C130A) strains were inoculated into mice and infectivity and dissemination assessed. While substitution of C130 with Ala prevents higher-order oligomerization, it did not abolish infectivity as inferred by seroconversion and the ability to cultivate spirochetes from ear punch biopsies of inoculated mice. Dissemination was assessed by cultivation of biopsy samples harvested at sites distal from the original inoculation site. An apparent difference in dissemination potential was not observed. These analyses definitively demonstrate that disulfide-bond-mediated oligomerization is not required for survival and dissemination within the mammalian host.

Recent efforts from our laboratory to generate a broadly protective, recombinant chimeric OspC-derived vaccine have focused on the generation of a chimera consisting primarily of the loop 5-helix 3 junction from diverse strains. This region of OspC has been shown to harbor linear epitopes that elicit bactericidal antibody (7, 11). The highly conserved C130 residue resides at the N-terminal end of this antigenic region. C130-mediated oligomerization and array formation at the cell surface could induce a T-independent humoral response, potentially impacting the memory response of vaccinees during infection. To assess this, serum was collected from the mice infected with each strain, and the IgG titer and antibody isotype patterns were determined. Titer and antibody isotype patterns were the same for mice infected with the wild-type strain and C130A substitution mutant strain. These data indicate that disulfide bond-mediated oligomerization does not significantly influence immune responses to OspC. The data also demonstrate that presentation of a potentially repetitive epitope, such as that which would be expected in an OspC higher-order oligomeric array, does not induce a type 2 T-cell-independent immune response (33).

In summary, it can be concluded that while OspC forms oligomers, disulfide-bond-mediated oligomerization is not required for OspC to function in the establishment of infection, dissemination, or the generation of a robust and potential productive antibody response.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dan Desrosiers and Justin Radolf for conducting circular dichroism analyses.

This work was supported by NIH NIAID grant AI67830.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anguita J., et al. 2002. Salp15, an Ixodes scapularis salivary protein, inhibits CD4(+) T cell activation. Immunity 16:849–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barbour A. G. 1984. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J. Biol. Med. 57:521–525 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benach J. L., et al. 1983. Spirochetes isolated from the blood of two patients with Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 308:740–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brisson D., Dykhuizen D. E. 2004. ospC diversity in Borrelia burgdorferi: different hosts are different niches. Genetics 168:713–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brisson D., Dykhuizen D. E., Ostfeld R. S. 2008. Conspicuous impacts of inconspicuous hosts on the Lyme disease epidemic. Proc. Biol. Sci. 275:227–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brooks C. S., Hefty P. S., Joliff S. E., Akins D. R. 2003. Global analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi genes regulated by mammalian host-specific signals. Infect. Immun. 71:3371–3383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buckles E. L., Earnhart C. G., Marconi R. T. 2006. Analysis of antibody response in humans to the type A OspC loop 5 domain and assessment of the potential utility of the loop 5 epitope in Lyme disease vaccine development. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13:1162–1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bunikis J., Barbour A. G. 1999. Access of antibody or trypsin to an integral outer membrane protein (P66) of Borrelia burgdorferi is hindered by Osp lipoproteins. Infect. Immun. 67:2874–2883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burgdorfer W., et al. 1982. Lyme disease—a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science 216:1317–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Das S., et al. 2001. Salp25D, an Ixodes scapularis antioxidant, is 1 of 14 immunodominant antigens in engorged tick salivary glands. J. Infect. Dis. 184:1056–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Earnhart C. G., Buckles E. L., Dumler J. S., Marconi R. T. 2005. Demonstration of OspC type diversity in invasive human Lyme disease isolates and identification of previously uncharacterized epitopes that define the specificity of the OspC murine antibody response. Infect. Immun. 73:7869–7877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Earnhart C. G., Buckles E. L., Marconi R. T. 2007. Development of an OspC-based tetravalent, recombinant, chimeric vaccinogen that elicits bactericidal antibody against diverse Lyme disease spirochete strains. Vaccine 25:466–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Earnhart C. G., et al. 2010. Identification of residues within ligand-binding domain 1 (LBD1) of the Borrelia burgdorferi OspC protein required for function in the mammalian environment. Mol. Microbiol. 76:393–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Earnhart C. G., Marconi R. T. 2007. Construction and analysis of variants of a polyvalent Lyme disease vaccine: approaches for improving the immune response to chimeric vaccinogens. Vaccine 25:3419–3427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Earnhart C. G., Marconi R. T. 2007. An octavalent Lyme disease vaccine induces antibodies that recognize all incorporated OspC type-specific sequences. Hum. Vaccin. 3:281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eicken C., et al. 2001. Crystal structure of Lyme disease antigen outer surface protein C from Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biol. Chem. 276:10010–10015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fuchs R., et al. 1992. Molecular analysis and expression of a Borrelia burgdorferi gene encoding a 22 kDa protein (pC) in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 6:503–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gern L., et al. 1998. European reservoir hosts of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 287:196–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gilmore R. D., Jr., Mbow M. L., Stevenson B. 2001. Analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression during life cycle phases of the tick vector Ixodes scapularis. Microbes Infect. 3:799–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grimm D., et al. 2004. Outer-surface protein C of the Lyme disease spirochete: a protein induced in ticks for infection of mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:3142–3147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hanincova K., Kurtenbach K., Diuk-Wasser M., Brei B., Fish D. 2006. Epidemic spread of Lyme borreliosis, northeastern United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:604–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hovius J. W., et al. 2008. Preferential protection of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto by a Salp15 homologue in Ixodes ricinus saliva. J. Infect. Dis. 198:1189–1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hovius J. W., van Dam A. P., Fikrig E. 2007. Tick-host-pathogen interactions in Lyme borreliosis. Trends Parasitol. 23:434–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang X., et al. 1999. 1H, 13C, and 15N NMR backbone assignments of 37 kDa surface antigen OspC from Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biomol. NMR 14:283–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kampen H., Rotzel D. C., Kurtenbach K., Maier W. A., Seitz H. M. 2004. Substantial rise in the prevalence of Lyme borreliosis spirochetes in a region of western Germany over a 10-year period. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1576–1582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kumaran D., Eswaramoorthy S., Dunn J. J., Swaminathan S. 2001. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein C (OspC). Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57:298–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kumaran D., et al. 2001. Crystal structure of outer surface protein C (OspC) from the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. EMBO J. 20:971–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. LaFleur R. L., et al. 2009. Bacterin that induces OspA and OspC borreliacidal antibodies provides a high level of protection against canine Lyme disease. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:253–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lagal V., Portnoi D., Faure G., Postic D., Baranton G. 2006. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto invasiveness is correlated with OspC-plasminogen affinity. Microbes Infect. 8:645–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lawson C. L., Yung B. H., Barbour A. G., Zuckert W. R. 2006. Crystal structure of neurotropism-associated variable surface protein 1 (Vsp1) of Borrelia turicatae. J. Bacteriol. 188:4522–4530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marconi R. T., Garon C. F. 1992. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Borrelia: a comparison of North American and European isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 174:241–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marconi R. T., Samuels D. S., Garon C. F. 1993. Transcriptional analyses and mapping of the ospC gene in Lyme disease spirochetes. J. Bacteriol. 175:926–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mathiesen M. J., et al. 1998. The dominant epitope of Borrelia garinii outer surface protein C recognized by sera from patients with neuroborreliosis has a surface-exposed conserved structural motif. Infect. Immun. 66:4073–4079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pal U., et al. 2004. OspC facilitates Borrelia burgdorferi invasion of Ixodes scapularis salivary glands. J. Clin. Invest. 113:220–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Purser J. E., Norris S. J. 2000. Correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:13865–13870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Radolf J. D., Bourell K. W., Akins D. R., Brusca J. S., Norgard M. V. 1994. Analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi membrane architecture by freeze-fracture electron microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 176:21–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Radolf J. D., Caimano M. J. 2008. The long strange trip of Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface protein C. Mol. Microbiol. 69:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ramamoorthi N., et al. 2005. The Lyme disease agent exploits a tick protein to infect the mammalian host. Nature 436:573–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rogers E. A., et al. 2009. Rrp1, a cyclic-di-GMP-producing response regulator, is an important regulator of Borrelia burgdorferi core cellular functions. Mol. Microbiol. 71:1551–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sadziene A., Wilske B., Ferdows M. S., Barbour A. G. 1993. The cryptic ospC gene of Borrelia burgdorferi B31 is located on a circular plasmid. Infect. Immun. 61:2192–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schagger H., Cramer W. A., von Jagow G. 1994. Analysis of molecular masses and oligomeric states of protein complexes by blue native electrophoresis and isolation of membrane protein complexes by two-dimensional native electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 217:220–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schwan T. G. 2003. Temporal regulation of outer surface proteins of the Lyme-disease spirochaete Borrelia burgdorferi. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:108–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schwan T. G., Piesman J., Golde W. T., Dolan M. C., Rosa P. A. 1995. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:2909–2913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Srivastava S. Y., de Silva A. M. 2008. Reciprocal expression of ospA and ospC in single cells of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 190:3429–3433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stevenson B., Schwan T. G., Rosa P. A. 1995. Temperature-related differential expression of antigens in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 63:4535–4539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stewart P. E., et al. 2006. Delineating the requirement for the Borrelia burgdorferi virulence factor OspC in the mammalian host. Infect. Immun. 74:3547–3553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tilly K., Bestor A., Jewett M. W., Rosa P. 2007. Rapid clearance of Lyme disease spirochetes lacking OspC from skin. Infect. Immun. 75:1517–1519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tilly K., et al. 1997. The Borrelia burgdorferi circular plasmid cp26: conservation of plasmid structure and targeted inactivation of the ospC gene. Mol. Microbiol. 25:361–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tilly K., et al. 2006. Borrelia burgdorferi OspC protein required exclusively in a crucial early stage of mammalian infection. Infect. Immun. 74:3554–3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vos Q., Lees A., Wu Z. Q., Snapper C. M., Mond J. J. 2000. B-cell activation by T-cell-independent type 2 antigens as an integral part of the humoral immune response to pathogenic microorganisms. Immunol. Rev. 176:154–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang I. N., et al. 1999. Genetic diversity of ospC in a local population of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Genetics 151:15–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zuckert W. R., Kerentseva T. A., Lawson C. L., Barbour A. G. 2001. Structural conservation of neurotropism-associated VspA within the variable Borrelia Vsp-OspC lipoprotein family. J. Biol. Chem. 276:457–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]