Abstract

Mycobacteria include a large number of pathogens. Identification to species level is important for diagnoses and treatments. Here, we report the development of a Web-accessible database of the hsp65 locus sequences (http://msis.mycobacteria.info) from 149 out of 150 Mycobacterium species/subspecies. This database can serve as a reference for identifying Mycobacterium species.

TEXT

Included among the mycobacteria are a large number of clinically important pathogens, both obligate (e.g., M. tuberculosis and M. leprae) and opportunistic (e.g., M. avium, M. kansasii, etc.). The impact of mycobacteria on human morbidity and mortality is hard to overstate. Although tuberculosis (TB) is arguably one of the most important infectious diseases in the world, the incidence of disease due to nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) has been steadily increasing worldwide (6, 27, 42, 48, 59) and has likely far surpassed TB in the United States (7). Thus, the American Thoracic Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America have recommended identifying the clinically significant NTM to the species level upon the diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases (17).

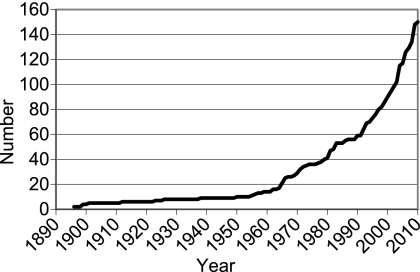

The Mycobacterium genus currently includes 150 species/subspecies (http://www.bacterio.cict.fr/m/mycobacterium.html), and the number has been increasing exponentially (Fig. 1), making identification difficult and challenging. Current identification based on biochemical tests of culture is slow and inadequate to differentiate among closely related mycobacteria, especially for those mycobacteria that are biochemically inert and slowly growing. In contrast, molecular identification methods based on PCR and nucleotide sequencing dramatically shorten the detection time and improve the accuracy of identification. The most common genomic loci used in molecular identification are the 16S rRNA gene (25), 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed spacer (15), hsp65 (40, 47), and rpoB (22). Almost all recent publications on new mycobacterial species compared sequences from multiple loci to those of established species, and hsp65 is always included. A previous study has shown a 99.1% agreement between identification using hsp65 sequencing and a conventional method combining Accuprobes, biochemical test panels, or 16S rRNA gene sequencing (33), suggesting that hsp65 sequencing is an effective method for identifying mycobacterial species. It was also suggested that completeness of the sequence database was critical for this identification method (33). To our knowledge, there is no publicly accessible hsp65 sequence database that covers all currently validated mycobacterial species. Laboratorians and researchers have to rely on the sequences deposited in public databases, such as GenBank, EMBL, and DDBJ. The vast majority of these mycobacterial entries are from uncharacterized strains or undetermined species, and problematic sequence entries, such as base errors, incomplete sequences, invalid or misidentified species, and even species-strain mismatches, are frequently present. This makes identification by searching public databases onerous and error prone. To facilitate the taxonomic identification of mycobacterial isolates, we have developed a Web-accessible database of mycobacterial hsp65 sequences from 149 species/subspecies, excluding the problematic GenBank entries mentioned above.

Fig. 1.

Numbers of approved Mycobacterium species/subspecies from 1896 to 2010.

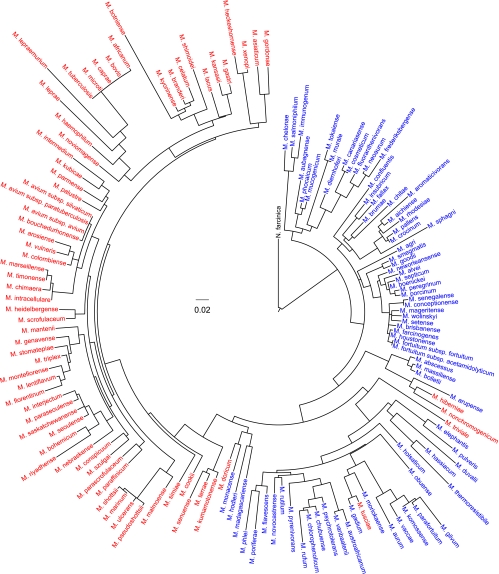

The type strain hsp65 sequences of 147 mycobacterial species/subspecies were downloaded from GenBank. M. lepraemurium and M. leprae do not have type strains due to difficult cultivation. We chose M. lepraemurium TS130 and M. leprae TN as their reference strains and obtained their hsp65 sequences with the GenBank sequence accession numbers AY550232 (34) and NC_002677 (11). Multiple identical GenBank sequences from the type strain of the same species were combined into a single entry in our database (Table 1). We trimmed the sequences to 401 bp, which corresponds to nucleotide positions 165 to 565 of the M. tuberculosis H37Rv hsp65 gene and can be amplified and sequenced using primers Tb11 and Tb12 (47). Entries that did not completely cover this 401-bp hsp65 locus were excluded from our database. Using previously described methods (13), we determined and verified 47 hsp65 sequences and submitted them to GenBank (bold accession numbers in Table 1). As a result of our verification, the incorrect sequences from M. asiaticum, M. flavescens, M. intracellulare, M. porcinum, M. senegalense, M. septicum, and M. szulgai in GenBank were excluded from our database, and only verified sequences of these species were adopted. Sequence similarities were determined by MEGA 5.02 (http://www.megasoftware.net/). Currently, there are a total of 143 unique sequences from 149 species/subspecies in this database. Identical sequences are found among the three M. avium subspecies, between two M. fortuitum subspecies, and among four M. tuberculosis complex members (i.e., M. bovis, M. caprae, M. microti, and M. tuberculosis). A BLAST server based on this database has been developed (http://msis.mycobacteria.info). Query sequences are accepted in FASTA format by copying and pasting or file uploading and then searched against the database using NCBI's BLASTN program. The output results will show 20 best hits to suggest their taxonomic categories at species level. The pairwise alignments and the percentages of identities are shown in the results as well. PhyML 3.0 (18) was used to generated a maximum-likelihood phylogeny of these 149 Mycobacterium species/subspecies (Fig. 2) that is the most complete so far, covering 99.3% of the Mycobacterium genus (the only missing species is M. pinnipedii, an M. tuberculosis complex member). Slowly growing mycobacteria (SGM) and rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM) are clearly separated, except that the slowly growing M. tusciae, M. hiberniae, M. nonchromogenicum, and M. triviale are grouped with the RGM.

Table 1.

List of the Mycobacterium species/subspecies, the reference strains (all are type strains except M. leprae TN and M. lepraemurium TS130), and the GenBank sequence accession numbers for their hsp65 sequences from published studies used to generate the database

| Species/subspeciesa | Reference strain | GenBank accession no. (reference[s])b |

|---|---|---|

| M. abscessus | CIP 104536 | AY458075 (2), AF547802 (19) |

| ATCC 19977 | EF486338 (24), AY498743 (43), NC_010397 (41), JF491290 | |

| M. africanum | CIP 105147 | AF547803 (14) |

| ATCC 25420 | FJ617583 (20), JF491313 | |

| M. agri | CIP 105391 | AY438080 |

| M. aichiense | ATCC 27280 | AY299147 (23) |

| DSM 44147 | AF547804 (14) | |

| M. alvei | CIP 103464 | AF547805 (14) |

| M. aromaticivorans | JS19b1 | DQ841182 (19) |

| M. arosiense | DSM 45069 | JF491321 |

| T1921 | EU370531 (4) | |

| ATCC BAA-1401 | GQ153297 (49) | |

| M. arupense | DSM 44942 | EU191917, GQ214503 (29), JF491325 |

| AR30097 | DQ168662 (9) | |

| M. asiaticum | ATCC 25276 | AY299133 (23), GU362517 (13) |

| M. aubagnense | CIP 108543 | AY859677 (1) |

| CCUG 50186 | DQ987727 | |

| M. aurum | ATCC 23366 | AF350414 (64), FJ172326 (44) |

| CIP 104465 | AY438081 | |

| M. austroafricanum | CIP 105395 | AF547807 (14) |

| M. avium subsp. avium | ATCC 25291 | AF126030 (28), EU239779 (5), GQ153289 (49), JF491291 |

| CIP 104244 | AF547808 (14) | |

| M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis | CIP 103963 | AF547809 (14) |

| ATCC 19698 | AY299137 (23) | |

| M. avium subsp. silvaticum | ATCC 49884 | EU239781 (5) |

| CIP 103317 | AF547810 (14) | |

| M. boenickei | CIP 107829 | AY943195 |

| M. bohemicum | CIP 105811 | AF547811 (14) |

| M. bolletii | CCUG 50184 | DQ987724 |

| CIP 108541 | EU266576, AY859675 (1), FJ607778 (26) | |

| M. botniense | DSM 44537 | AF547812 (14) |

| M. bouchedurhonense | CIP 109827 | HM602039 |

| M. bovis | CIP 105234 | AF547813 (14) |

| ATCC 19210 | JF491332 | |

| M. branderi | CIP 104592 | AF547815 (14) |

| M. brisbanense | DSM 44680 | AB456564, JF491333 |

| CIP 107830 | AY943196 | |

| M. brumae | CIP 103465 | AF547816 (14) |

| M. canariasense | 502329 | AY255477 (21) |

| DSM 44828 | JF491316 | |

| M. caprae | CIP 105776 | AF547884 (14) |

| M. celatum | ATCC 51131 | AY299180 (23), JF491292 |

| CIP 106109 | AF547817 (14) | |

| M. chelonae | CIP 104535 | AF547818 (14), AY458074 (2) |

| ATCC 35752 | JF491293 | |

| M. chimaera | CIP 107892 | GQ153296 (49), AY943198 |

| DSM 44623 | EU239783 (5) | |

| M. chitae | CIP 105383 | AF547819 (14) |

| ATCC 19627 | AY299149 (23) | |

| M. chlorophenolicum | CIP 104189 | AF547820 (14) |

| M. chubuense | CIP 106810 | AF547821 (14) |

| M. colombiense | CIP 108962 | EU239785 (5), GQ153298 (49) |

| M. conceptionense | CIP 108544 | AM902957 (39), EU191920, AY859678 (1) |

| M. confluentis | CIP 105510 | AF547822 (14) |

| M. conspicuum | CIP 105165 | AF547823 (14) |

| M. cookie | CIP 105396 | AF547824 (14) |

| M. cosmeticum | LTA-388 | AY449730 (12) |

| DSM 44829 | DQ124111 | |

| M. crocinum | czh-42 | DQ533998 (19) |

| M. diernhoferi | CIP 105384 | AF547825 (14) |

| M. doricum | DSM 44339 | AF547826 (14) |

| M. duvalii | CIP 104539 | AF547827 (14) |

| M. elephantis | CIP 106831 | AF547828 (14) |

| M. fallax | CIP 81.39 | AF547829 (14) |

| ATCC 35219 | JF491294 | |

| M. farcinogenes | ATCC 35753 | AY299150 (23) |

| DSM 43637 | AF547830 (14) | |

| NCTC 10955 | AY458073 (2) | |

| M. flavescens | ATCC 14474 | AF350413 (64), GU362519 (13) |

| M. florentinum | DSM 44852 | DQ350162, JF491317 |

| M. fluoranthenivorans | DSM 44556 | DQ350157, JF491318 |

| M. fortuitum subsp. acetamidolyticum | CIP 105423 | AF547832 (14) |

| ATCC 35931 | JF491314 | |

| M. fortuitum subsp. fortuitum | CIP 104534 | AF547833 (14) |

| ATCC 6841 | JF491295 | |

| M. frederiksbergense | DSM 44346 | AF547834 (14) |

| M. gadium | CIP 105388 | AF547835 (14) |

| M. gastri | CIP 104530 | AF547836 (14) |

| ATCC 15754 | JF491315 | |

| M. genavense | DSM 44424 | AF547837 (14) |

| M. gilvum | DSM 44503 | AF547838 (14) |

| M. goodii | CIP 106349 | AF547839 (14) |

| ATCC 700504 | AY458071 (2) | |

| M. gordonae | CIP 104529 | AF547840 (14) |

| ATCC 14470 | AF434734 | |

| M. haemophilum | CIP 105049 | AF547841 (14) |

| ATCC 29548 | AY299185, GQ245967, JF491296 | |

| M. hassiacum | CIP 105218 | AF547842 (14) |

| M. heckeshornense | DSM 44428 | AF547843 (14) |

| M. heidelbergense | CIP 105424 | AF547844 (14) |

| M. hiberniae | DSM 44241 | AY438083 |

| ATCC 49874 | JF491297 | |

| M. hodleri | CIP 104909 | AF547845 (14) |

| M. holsaticum | DSM 44478 | AY438084 |

| M. houstonense | ATCC 49403 | AY458077 (2) |

| DSM 44676 | DQ987725 | |

| M. immunogenum | CIP 106684 | AY458081 (2), EU266577 |

| M. insubricum | DSM 45132 | JF491319 |

| FI-06250 | EF584487 (51) | |

| M. interjectum | DSM 44064 | AF547846 (14) |

| ATCC 51457 | JF491298 | |

| M. intermedium | CIP 104542 | AF547847 (14) |

| ATCC 51848 | AY299187 | |

| M. intracellulare | ATCC 13950 | AF126035 (28), DQ284774 (53), GQ153290 (49), JF491299 |

| TMC 1406 | U85633 (46) | |

| M. kansasii | CIP 104589 | AF547849 (14) |

| ATCC 12478 | AF434739, AY299189, JF491300 | |

| M. komossense | CIP 105293 | AY438649 |

| M. kubicae | CIP 106428 | AF547850 (14) |

| ATCC 700732 | AY373458 (23) | |

| M. kumamotonense | CST 7247 | AB239920 (32) |

| CCUG 51961 | EU191915 | |

| DSM 45093 | JF491323 | |

| M. kyorinense | KUM 060204 | AB370171 (37) |

| DSM 45166 | HM602040 | |

| M. lacus | DSM 44577 | AY438090 |

| M. leprae | TN | NC_002677 (11) |

| M. lepraemurium | TS130 | AY550232 (34) |

| M. lentiflavum | CIP 105465 | AF547851 (14) |

| M. llatzerense | MG13 | AM421341 (16) |

| DSM 45343 | JF491330 | |

| M. madagascariense | CIP 104538 | AF547852 (14) |

| M. mageritense | CIP 104973 | AY458070 (2), AF547853 (14) |

| M. malmoense | CIP 105775 | AF547854 (14) |

| ATCC 29571 | GQ153293 (49), JF491301 | |

| M. mantenii | NLA000401474 | FJ232523 (60) |

| CIP 109863 | HM602041 | |

| M. marinum | ATCC 927 | AY299134 (23), AF456470 (55), AB548715 |

| NCTC 2275 | AF271346 (45) | |

| CIP 104528 | AF547855 (14) | |

| M. marseillense | 5356591 | EU239787 (5) |

| CIP 109828 | HM602037 | |

| M. massiliense | CIP 108297 | EU191919, EF486339 (24), EU266578 |

| CCUG 48898 | AY596465 (3) | |

| M. microti | CIP 104256 | AF547856 (14) |

| ATCC 19422 | AY299135 (23) | |

| M. monacense | DSM 44395 | EU191918, JF491320 |

| M. montefiorense | DSM 44602 | AY943204 |

| ATCC BAA-256 | AY027785 (31) | |

| M. moriokaense | CIP 105393 | AF547857 (14), AY859680 (1) |

| M. mucogenicum | ATCC 49650 | AY299155, AY458079 (2) |

| M. murale | CIP 105980 | AF547859 (14) |

| M. nebraskense | DSM 44803 | DQ124110 |

| ATCC BAA-837 | GQ153294 (49) | |

| UNMC-MY1349 | AY368457 (35) | |

| M. neoaurum | ATCC 25795 | AY299156, FJ172320 (44), JF491302 |

| CIP 105387 | AF547860 (14) | |

| M. neworleansense | CIP 107827 | AY943199 |

| ATCC 49404 | AY458076 (2), AY496143 (62) | |

| M. nonchromogenicum | DSM 44164 | AF547861 (14) |

| ATCC 19530 | AY299136 (23), AF434732, JF491303 | |

| M. noviomagense | NLA000500338 | EU600390 (57) |

| M. novocastrense | CIP 105546 | AF547862 (14) |

| M. obuense | CIP 106803 | AF547863 (14) |

| M. pallens | czh-8 | DQ533997 (19) |

| M. palustre | DSM 44572 | AY943200 |

| M. paraffinicum | ATCC 12670 | GQ153287 (49) |

| M. parafortuitum | CIP 106802 | AF547864 (14) |

| M. parascrofulaceum | ATCC BAA-614 | AY337274 (52), GQ153295 (49) |

| CIP 108112 | AY943201 | |

| M. paraseoulense | DSM 45000 | HM602042, JF491324 |

| 31118 | DQ536402 | |

| M. parmense | CIP 107385 | HM022199 |

| M. peregrinum | NCTC 10264 | AM902953 (39) |

| CIP 105382 | AY458069 (2), AF547865 (14) | |

| ATCC 14467 | AY299159 (23) | |

| M. phlei | ATCC 11758 | AY299158 (23) |

| CIP 105389 | AF547866 (14) | |

| M. phocaicum | CCUG 50185 | DQ987726 |

| CIP 108542 | AY859676 (1), EU266579 | |

| M. porcinum | ATCC 33776 | AY496137 (62), JF491326 |

| M. poriferae | CIP 105394 | AF547868 (14) |

| M. pseudoshottsii | NCTC 13318 | AM902956 (39), DQ987722 |

| ATCC BAA-883 | AY571788 | |

| M. psychrotolerans | DSM 44697 | HM602035 |

| M. pulveris | CIP 106804 | AF547869 (14) |

| M. pyrenivorans | DSM 44605 | JF510463 |

| M. rhodesiae | CIP 106806 | AF547870 (14) |

| M. riyadhense | NLA000201958 | EU921671 (56) |

| M. rufum | JS14 | DQ841181 (19) |

| M. rutilum | czh-117 | DQ841180 (19) |

| M. salmoniphilum | ATCC 13758 | DQ866777 (63) |

| M. saskatchewanense | NRCM 00-250; ATCC BAA-544 | AY208858 (54) |

| CIP 108114 | AY943203 | |

| DSM 44616 | JF491331 | |

| M. scrofulaceum | ATCC 19981 | GQ153288 (49), AF434733, AY299138 (23), JF491304 |

| CIP 105416 | AF547871 (14) | |

| M. senegalense | NCTC 10956 | AM902954 (39) |

| ATCC 35796 | AY684045 (61), JF491327 | |

| M. senuense | DSM 44999 | FJ268582, JF491328 |

| 05-832 | DQ536409 (36) | |

| M. seoulense | DSM 44998 | EU191916, JF491322 |

| M. septicum | ATCC 700731 | AY373457 (23), AY496142 (62) |

| DSM 44393 | JF491329 | |

| M. setense | CIP 109395 | EU371505 (50) |

| M. shimoidei | DSM 44152 | AF547874 (14) |

| ATCC 27962 | JF491305 | |

| M. shottsii | NCTC 13215T | AM902955 (39), DQ987723 |

| ATCC 700981 | AY550225 (34), EU619895 | |

| M. simiae | CIP 104531 | AF547875 (14) |

| ATCC 25275 | GQ153292 (49), AF434730, JF491306 | |

| M. smegmatis | ATCC 19420 | AY458065 (2), JF491307 |

| CIP 104444 | AF547876 (14) | |

| M. sphagni | DSM 44076 | AF547877 (14) |

| M. stomatepiae | DSM 45059T | AM902968 (38, 39) |

| M. szulgai | ATCC 35799 | AF350412 (64), AY299141 (23), JF491308 |

| CIP 104532 | AF547878 (14) | |

| M. terrae | ATCC 15755 | AF257468, AF434736, AY299142 (23) |

| CIP 104321 | AF547879 (14) | |

| M. thermoresistibile | CIP 105390 | AF547880 (14) |

| M. timonense | CIP 109830 | HM602038 |

| M. tokaiense | CIP 106807 | AF547881 (14) |

| ATCC 27282 | JF491309 | |

| M. triplex | ATCC 700071 | AY027786 (31), GQ153291 (49) |

| CIP 106108 | AF547882 (14) | |

| M. triviale | DSM 44153 | AF547883 (14) |

| ATCC 23292 | AF434737, AY299143 (23), JF491310 | |

| M. tuberculosis | ATCC 27294 | AY299144 (23), JF491311 |

| H37Rv | NC_000962 (8, 10) | |

| M. tusciae | CIP 106367 | AF547887 (14) |

| M. ulcerans | ATCC 19423 | AY299145 (23), AB548723, AF271096 (45) |

| M. vaccae | CIP 105934 | AF547889 (14) |

| ATCC 15483 | JF491312 | |

| M. vanbaalenii | DSM 7251 | AY438091 |

| PYR-1 | NC_008726 | |

| M. vulneris | NLA000700772 | EU834054 (58) |

| M. wolinskyi | CIP 106348 | AF547890 (14) |

| ATCC 700010 | AY299164 (23), AY458064 (2) | |

| M. xenopi | CIP 104035 | AF547891 (14) |

| ATCC 19250 | AF434738, AY373454 (23) |

The sequences of 47 species/subspecies (boldface) were validated by our laboratory. The sequences of 40 species/subspecies (underlined) are supported by multiple GenBank records deposited by other research groups.

Accession numbers in bold are for sequences determined in our laboratory.

Fig. 2.

Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of Mycobacterium genus. PhyML 3.0 with default settings (18) and iTOL (30) were used to generate the circular phylogenic tree rooted with Nocardia farcinica (strain IFM 10152). Rapidly growing mycobacteria are in blue, while slowly growing mycobacteria are in red. The scale bar is equivalent to 0.02 substitution/site.

The popularity of species identification using hsp65 sequences has resulted in a large number of mycobacterial hsp65 sequences being deposited in public repositories. McNabb et al. also developed an in-house database, including 111 Mycobacterium species (34). The accuracy and coverage are crucial for the database to become a viable solution for species identification. Here, we report a publicly accessible hsp65 database with 99.3% coverage of the entire Mycobacterium genus, of which 47 species/subspecies have been verified in our laboratory (boldface in Table 1) and 40 entries are supported by multiple GenBank sequences and thus are considered confirmed sequences (underlined in Table 1). A 97% identity was previously suggested as a criterion for identifying a species using hsp65 sequences (34). However, pairwise comparison of these 149 species identified 219, 121, and 45 instances of sequence similarity greater than 97%, 98%, and 99%, involving 94 (63.1%), 82 (55.0%), and 42 (28.2%) species/subspecies, respectively (see the table in the supplemental material). This makes the identification of species with less than 100% matches challenging. Because the interspecies similarities vary from group to group in the phylogeny and change as the number of species/subspecies increases, investigators need to be cautious when assigning species/subspecies for these isolates. Further research is needed to establish a more reliable criterion and validate our database with clinical and environmental isolates. Nevertheless, our database provides the most comprehensive phylogenetic information on the mycobacterial hsp65 locus that can facilitate species identification in this genus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jack Crawford for thoughtful suggestions and helpful comments.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 30 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adekambi T., Berger P., Raoult D., Drancourt M. 2006. rpoB gene sequence-based characterization of emerging non-tuberculous mycobacteria with descriptions of Mycobacterium bolletii sp. nov., Mycobacterium phocaicum sp. nov. and Mycobacterium aubagnense sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56:133–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adekambi T., Drancourt M. 2004. Dissection of phylogenetic relationships among 19 rapidly growing Mycobacterium species by 16S rRNA, hsp65, sodA, recA and rpoB gene sequencing. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:2095–2105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adekambi T., et al. 2004. Amoebal coculture of “Mycobacterium massiliense” sp. nov. from the sputum of a patient with hemoptoic pneumonia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5493–5501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bang D., et al. 2008. Mycobacterium arosiense sp. nov., a slowly growing, scotochromogenic species causing osteomyelitis in an immunocompromised child. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58:2398–2402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ben Salah I., Adekambi T., Raoult D., Drancourt M. 2008. rpoB sequence-based identification of Mycobacterium avium complex species. Microbiology 154:3715–3723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bodle E. E., Cunningham J. A., Della-Latta P., Schluger N. W., Saiman L. 2008. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients without HIV infection, New York City. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:390–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Butler W. R., Crawford J. T. 1999. Nontuberculous mycobacteria reported to the public health laboratory information system by state public health laboratories, United States, 1993–1996. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA [Google Scholar]

- 8. Camus J. C., Pryor M. J., Medigue C., Cole S. T. 2002. Re-annotation of the genome sequence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Microbiology 148:2967–2973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cloud J. L., et al. 2006. Mycobacterium arupense sp. nov., a non-chromogenic bacterium isolated from clinical specimens. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56:1413–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cole S. T., et al. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cole S. T., et al. 2001. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature 409:1007–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cooksey R. C., et al. 2004. Mycobacterium cosmeticum sp. nov., a novel rapidly growing species isolated from a cosmetic infection and from a nail salon. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:2385–2391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dai J., et al. 2011. Multiple-genome comparison reveals new loci for Mycobacterium species identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:144–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Devulder G., Perouse de Montclos M., Flandrois J. P. 2005. A multigene approach to phylogenetic analysis using the genus Mycobacterium as a model. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55:293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frothingham R., Wilson K. H. 1993. Sequence-based differentiation of strains in the Mycobacterium avium complex. J. Bacteriol. 175:2818–2825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gomila M., Ramirez A., Lalucat J. 2007. Diversity of environmental Mycobacterium isolates from hemodialysis water as shown by a multigene sequencing approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3787–3797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Griffith D. E., et al. 2007. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175:367–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guindon S., et al. 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59:307–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hennessee C. T., Seo J. S., Alvarez A. M., Li Q. X. 2009. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading species isolated from Hawaiian soils: Mycobacterium crocinum sp. nov., Mycobacterium pallens sp. nov., Mycobacterium rutilum sp. nov., Mycobacterium rufum sp. nov. and Mycobacterium aromaticivorans sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59:378–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huard R. C., et al. 2006. Novel genetic polymorphisms that further delineate the phylogeny of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J. Bacteriol. 188:4271–4287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jimenez M. S., et al. 2004. Mycobacterium canariasense sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1729–1734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim B. J., et al. 1999. Identification of mycobacterial species by comparative sequence analysis of the RNA polymerase gene (rpoB). J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1714–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim H., et al. 2005. Differentiation of Mycobacterium species by analysis of the heat-shock protein 65 gene (hsp65). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55:1649–1656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim H. Y., et al. 2007. Outbreak of Mycobacterium massiliense infection associated with intramuscular injections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3127–3130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kirschner P., Bottger E. C. 1998. Species identification of mycobacteria using rDNA sequencing. Methods Mol. Biol. 101:349–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koh W. J., et al. 2009. First case of disseminated Mycobacterium bolletii infection in a young adult patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3362–3366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lai C. C., et al. 2010. Increasing incidence of nontuberculous mycobacteria, Taiwan, 2000-2008. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:294–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leao S. C., et al. 1999. Identification of two novel Mycobacterium avium allelic variants in pig and human isolates from Brazil by PCR-restriction enzyme analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2592–2597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee H., et al. 2010. Mycobacterium paraterrae sp. nov. recovered from a clinical specimen: novel chromogenic slow growing mycobacteria related to Mycobacterium terrae complex. Microbiol. Immunol. 54:46–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Letunic I., Bork P. 2007. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics 23:127–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Levi M. H., et al. 2003. Characterization of Mycobacterium montefiorense sp. nov., a novel pathogenic Mycobacterium from moray eels that is related to Mycobacterium triplex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2147–2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Masaki T., et al. 2006. Mycobacterium kumamotonense sp. nov. recovered from clinical specimen and the first isolation report of Mycobacterium arupense in Japan: novel slowly growing, nonchromogenic clinical isolates related to Mycobacterium terrae complex. Microbiol. Immunol. 50:889–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McNabb A., Adie K., Rodrigues M., Black W. A., Isaac-Renton J. 2006. Direct identification of mycobacteria in primary liquid detection media by partial sequencing of the 65-kilodalton heat shock protein gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:60–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McNabb A., et al. 2004. Assessment of partial sequencing of the 65-kilodalton heat shock protein gene (hsp65) for routine identification of Mycobacterium species isolated from clinical sources. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3000–3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mohamed A. M., Iwen P. C., Tarantolo S., Hinrichs S. H. 2004. Mycobacterium nebraskense sp. nov., a novel slowly growing scotochromogenic species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:2057–2060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mun H. S., et al. 2008. Mycobacterium senuense sp. nov., a slowly growing, non-chromogenic species closely related to the Mycobacterium terrae complex. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58:641–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Okazaki M., et al. 2009. Mycobacterium kyorinense sp. nov., a novel, slow-growing species, related to Mycobacterium celatum, isolated from human clinical specimens. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59:1336–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pourahmad F., et al. 2008. Mycobacterium stomatepiae sp. nov., a slowly growing, non-chromogenic species isolated from fish. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58:2821–2827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pourahmad F., Thompson K. D., Adams A., Richards R. H. 2009. Comparative evaluation of polymerase chain reaction-restriction enzyme analysis (PRA) and sequencing of heat shock protein 65 (hsp65) gene for identification of aquatic mycobacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 76:128–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ringuet H., et al. 1999. hsp65 sequencing for identification of rapidly growing mycobacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:852–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ripoll F., et al. 2009. Non mycobacterial virulence genes in the genome of the emerging pathogen Mycobacterium abscessus. PLoS One 4:e5660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ryoo S. W., et al. 2008. Spread of nontuberculous mycobacteria from 1993 to 2006 in Koreans. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 22:415–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Selvaraju S. B., Khan I. U., Yadav J. S. 2005. A new method for species identification and differentiation of Mycobacterium chelonae complex based on amplified hsp65 restriction analysis (AHSPRA). Mol. Cell. Probes 19:93–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Simmon K. E., Low Y. Y., Brown-Elliott B. A., Wallace R. J., Jr., Petti C. A. 2009. Phylogenetic analysis of Mycobacterium aurum and Mycobacterium neoaurum with redescription of M. aurum culture collection strains. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 59:1371–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stinear T. P., Jenkin G. A., Johnson P. D., Davies J. K. 2000. Comparative genetic analysis of Mycobacterium ulcerans and Mycobacterium marinum reveals evidence of recent divergence. J. Bacteriol. 182:6322–6330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Swanson D. S., et al. 1997. Subspecific differentiation of Mycobacterium avium complex strains by automated sequencing of a region of the gene (hsp65) encoding a 65-kilodalton heat shock protein. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:414–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Telenti A., et al. 1993. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:175–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thomson R. M., NTM working group at Queensland TB Control Centre, and Queensland Mycobacterial Reference Laboratory 2010. Changing epidemiology of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:1576–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Toney N., Adekambi T., Toney S., Yakrus M., Butler W. R. 2010. Revival and emended description of ‘Mycobacterium paraffinicum’ Davis, Chase and Raymond 1956 as Mycobacterium paraffinicum sp. nov., nom. rev. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60:2307–2313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Toro A., Adekambi T., Cheynet F., Fournier P. E., Drancourt M. 2008. Mycobacterium setense infection in humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1330–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tortoli E., et al. 2009. Mycobacterium insubricum sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59:1518–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Turenne C. Y., et al. 2004. Mycobacterium parascrofulaceum sp. nov., novel slowly growing, scotochromogenic clinical isolates related to Mycobacterium simiae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1543–1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Turenne C. Y., Semret M., Cousins D. V., Collins D. M., Behr M. A. 2006. Sequencing of hsp65 distinguishes among subsets of the Mycobacterium avium complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:433–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Turenne C. Y., et al. 2004. Mycobacterium saskatchewanense sp. nov., a novel slowly growing scotochromogenic species from human clinical isolates related to Mycobacterium interjectum and Accuprobe-positive for Mycobacterium avium complex. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:659–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ucko M., et al. 2002. Strain variation in Mycobacterium marinum fish isolates. Appl. Environ. microbiol. 68:5281–5287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. van Ingen J., et al. 2009. Mycobacterium riyadhense sp. nov., a non-tuberculous species identified as Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by a commercial line-probe assay. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59:1049–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. van Ingen J., et al. 2009. Mycobacterium noviomagense sp. nov.; clinical relevance evaluated in 17 patients. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59:845–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. van Ingen J., et al. 2009. Proposal to elevate Mycobacterium avium complex ITS sequevar MAC-Q to Mycobacterium vulneris sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59:2277–2282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. van Ingen J., Hoefsloot W., Dekhuijzen P. N., Boeree M. J., van Soolingen D. 2010. The changing pattern of clinical Mycobacterium avium isolation in the Netherlands. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 14:1176–1180 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. van Ingen J., et al. 2009. Mycobacterium mantenii sp. nov., a pathogenic, slowly growing, scotochromogenic species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59:2782–2787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wallace R. J., Jr., et al. 2005. Polyphasic characterization reveals that the human pathogen Mycobacterium peregrinum type II belongs to the bovine pathogen species Mycobacterium senegalense. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5925–5935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wallace R. J., Jr., et al. 2004. Clinical and laboratory features of Mycobacterium porcinum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5689–5697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Whipps C. M., Butler W. R., Pourahmad F., Watral V. G., Kent M. L. 2007. Molecular systematics support the revival of Mycobacterium salmoniphilum (ex Ross 1960) sp. nov., nom. rev., a species closely related to Mycobacterium chelonae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57:2525–2531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wong D. A., Yip P. C., Cheung D. T., Kam K. M. 2001. Simple and rational approach to the identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium complex species, and other commonly isolated mycobacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3768–3771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.