Abstract

Several members of the fungal genera Phialemonium and Lecythophora are occasional agents of severe human and animal infections. These species are difficult to identify, and relatively little is known about their frequency in the clinical setting. The objective of this study was to characterize morphologically and molecularly, on the basis of the analysis of large-subunit ribosomal DNA sequences, a set of 68 clinical isolates presumed to belong to these genera. A total of 59 isolates were determined to be Phialemonium species (n = 32) or a related Cephalotheca species (n = 6) or Lecythophora species (n = 20) or a related Coniochaeta species (n = 1). Nine isolates identified to be Acremonium spp. or Phaeoacremonium spp. were excluded from further study. The most common species were Phialemonium obovatum and Phialemonium curvatum, followed by Lecythophora hoffmannii, Cephalotheca foveolata, and Lecythophora mutabilis.

INTRODUCTION

A wide range of fungi are able to cause opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients. Apart from the genera Aspergillus, Scedosporium, and Fusarium, which are the most common filamentous fungal opportunists, many other genera, including Phialemonium and Lecythophora, are also involved in human infections, often with a fatal outcome (7, 19). Phialemonium and Lecythophora species are poorly differentiated morphologically, are difficult to identify, and may be confused with poorly sporulating Fusarium or Acremonium species. With the increasing number of susceptible, immunocompromised hosts, the early recognition of these potentially lethal fungi has become important in providing appropriate patient management (12, 20).

Phialemonium species are widely distributed in the environment, having been isolated from air, soil, industrial water, and sewage (9). Although they show pale colonies in vitro, melanin can be demonstrated in their cell wall by Fontana-Masson stain; for this reason, they are considered dematiaceous fungi (11, 33). The majority of Phialemonium infections are invasive, affecting both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients, and the more frequent infections include peritonitis, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and cutaneous infections of wounds following burns (7, 12, 15, 20, 23).

The genus Phialemonium was described by Gams and McGinnis (9) to accommodate filamentous fungi with morphological features between those of Acremonium and Phialophora. It is characterized by moist colonies with abundant adelophialides (reduced phialides that are not delimited from subtending intercalary hyphal cells by a basal septum) and less common discrete phialides (phialides clearly differentiated from the subtended hyphae and separated by a basal septum), with neither having conspicuous collarettes and with both producing conidia aggregate in slimy heads. On the basis of the conidial shape and the color of the colonies, three species have been described: Phialemonium obovatum, P. curvatum, and P. dimorphosporum (9). Phialemonium obovatum has greenish colonies and obovate conidia, P. curvatum typically has white to grayish colonies and allantoid conidia, and P. dimorphosporum was described as having grayish colonies with obovate or ellipsoidal conidia (7, 9, 15). Subsequently, P. dimorphosporum, on the basis of restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, was reduced to synonymy with P. curvatum; the morphologies ascribed to both species apply to P. curvatum (12). Recently, the new species Cephalotheca foveolata (family Cephalothecaceae), molecularly and morphologically related to P. obovatum, was reported to be the cause of a subcutaneous infection in a patient from South Korea (34).

The genus Lecythophora is morphologically similar to Phialemonium. It also forms adelophialides, but in Lecythophora, these conidiogenous cells show conspicuous collarettes, and the colonies usually are pink-salmon to dark brown, although discrete phialides like those of Acremonium may be also present (7, 9, 23, 30). Recently, molecular studies confirmed that the six species included in Lecythophora are anamorphs of Coniochaeta, an ascomycete genus belonging to the family Coniochaetaceae (Sordariomycetes) (6, 13, 31). Although these fungi are saprobes, some species have also been involved in human disease. Lecythophora hoffmannii has been associated with cases of subcutaneous infections, keratitis, sinusitis, peritonitis, and canine osteomyelitis (16, 21). Lecythophora mutabilis has been described to be the causative agent of human peritonitis, endocarditis, endophthalmitis, and keratitis, among others (2, 7, 8, 22, 28).

Due to the difficulties in the identification of the members of these two genera, their real incidence in human infections and the management of such infections are poorly known. Up to now, studies involving members of these genera isolated from clinical samples have been scarce, and generally, only a few isolates from medical cases have been molecularly or morphologically characterized. To evaluate the potential incidence of the different species of Phialemonium and Lecythophora in human infections, we have studied a large number of isolates of both genera from clinical samples received in a U.S. fungal reference laboratory during the period from 2001 to 2009. It is important to note that we lack sufficient clinical information to ascertain whether any of these isolates was confirmed to be the causal agent of infection. In order to provide the reliable identification of such isolates, apart from the morphological study, sequences of the D1/D2 domains of the 28S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) were also analyzed. Several molecular studies have demonstrated that this locus is a highly informative phylogenetic marker for these genera and its relatives (1, 6, 31, 34).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal isolates.

A total of 68 clinical isolates, presumably belonging to the genera Phialemonium and Lecythophora, received in the Fungus Testing Laboratory at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSC) for identification and/or antifungal susceptibility determination were included in this study (Table 1). In addition, 10 reference or type strains of different species of these genera, mainly provided by the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS; Utrecht, Netherlands), were also tested.

Table 1.

Phialemonium and Lecythophora clinical isolates and types or reference strains of related species included in the study

| Isolatea | Species | Origin | GenBank accession no. (D1/D2 rDNA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| UTHSC 01-20 (1) | Lecythophora sp. 1 | Leg wound, MA | |

| UTHSC 01-20 (2) | Lecythophora hoffmannii | Leg wound, MA | FR745935 |

| UTHSC 01-317 | Phialemonium obovatum | Graft tissue, WA | FR745951 |

| UTHSC 01-590 | Phialemonium obovatum | Toenail, TX | FR691999 |

| UTHSC 01-1399 | Phialemonium obovatum | Abscess, MD | FR745945 |

| UTHSC 01-1644 | Lecythophora sp. 1 | Canine bone marrow aspirate, AL | |

| UTHSC 01-1664 | Lecythophora sp. 4 | Arm wound, CA | |

| UTHSC 02-294 | Phialemonium obovatum | Blood, TX | FR745947 |

| UTHSC 02-875 | Phialemonium obovatum | Blood, TX | FR745948 |

| UTHSC 02-1109 | Lecythophora hoffmannii | Finger cyst fluid, CO | FR691983 |

| UTHSC 02-1327 | Coniochaeta prunicola | Canine skin mass, NY | FR691989 |

| UTHSC 02-2050 | Phialemonium curvatum | Forearm, FL | FR691978 |

| UTHSC 03-1149 | Lecythophora lignicola | Fingernail, PA | FR745938 |

| UTHSC 03-1890 | Lecythophora hoffmannii | Canine osteomyelitis, CA | FR745936 |

| UTHSC 03-2258 | Phialemonium obovatum | Arm, UT | FR745950 |

| UTHSC 03-2653 | Cephalotheca foveolata | Endocarditis, Singapore | FR745941 |

| UTHSC 03-3574 | Phialemonium obovatum | Blood, VA | FR692002 |

| UTHSC 03-3588 | Phialemonium obovatum | Bronchial fluid, TX | FR745946 |

| UTHSC 03-3661 | Phialemonium sp. 2 | Sinus, IL | |

| UTHSC 04-350 | Phialemonium curvatum | Synovial fluid, OH | FR691979 |

| UTHSC 04-616 | Phialemonium obovatum | Arm, TX | FR745944 |

| UTHSC 04-956 | Phialemonium curvatum | Sinus, MN | FR745926 |

| UTHSC 05-970 | Lecythophora mutabilis | Aortic valve, MA | FR691992 |

| UTHSC 05-2527 | Phialemonium sp. 1 | Peritoneal dialysis catheter, PA | |

| UTHSC 05-2926 | Lecythophora sp. 4 | Urine, TX | |

| UTHSC 05-3214 | Lecythophora hoffmannii | Vitreous fluid, OR | FR745934 |

| UTHSC 06-733 | Cephalotheca foveolata | Lymph node, TX | FR745943 |

| UTHSC 06-1277 | Phialemonium obovatum | Toenail, FL | FR745952 |

| UTHSC 06-1465 | Phialemonium sp. 1 | Shin aspirate, SC | |

| UTHSC 06-1664 | Lecythophora mutabilis | Vitreous fluid, MN | FR691991 |

| UTHSC 06-1820 | Phialemonium sp. 1 | Corneal fluid, FL | |

| UTHSC 06-2147 | Phialemonium curvatum | Nail, WA | FR745928 |

| UTHSC 06-4324 | Phialemonium curvatum | Canine pleural fluid, TX | FR691981 |

| UTHSC 07-11 | Phialemonium curvatum | CSF,b MN | FR745929 |

| UTHSC 07-1284 | Phialemonium curvatum | Toenail, SC | FR691980 |

| UTHSC 07-1556 | Cephalotheca foveolata | Bronchial fluid, SC | FR691996 |

| UTHSC 07-1957 | Lecythophora sp. 2 | Epidural fluid, MO | |

| UTHSC 07-2087 | Cephalotheca foveolata | Lymph node, TX | FR745942 |

| UTHSC 07-2173 | Phialemonium curvatum | Vitreous fluid, NV | FR745930 |

| UTHSC 07-2959 | Lecythophora mutabilis | Elbow, AR | FR745940 |

| UTHSC 07-3574 | Cephalotheca foveolata | Eyes, OH | FR691994 |

| UTHSC 07-3736 | Phialemonium sp. 1 | Left hand, FL | |

| UTHSC 08-185 | Lecythophora mutabilis | Nail, PA | FR745939 |

| UTHSC 08-693 | Phialemonium curvatum | CSF, TX | FR745932 |

| UTHSC 08-851 | Lecythophora hoffmannii | Eye, MN | FR691984 |

| UTHSC 08-1239 | Lecythophora hoffmannii | Canine urine, CA | FR745937 |

| UTHSC 08-2292 | Phialemonium curvatum | Blood, UT | FR745925 |

| UTHSC 08-2569 | Lecythophora hoffmannii | Bronchial fluid, MI | FR691985 |

| UTHSC 08-2766 | Cephalotheca foveolata | Eye capsule, NC | FR691995 |

| UTHSC 08-3008 | Lecythophora mutabilis | Leg, MN | FR691993 |

| UTHSC 08-3010 | Lecythophora hoffmannii | Bone, CA | FR745933 |

| UTHSC 08-3486 | Phialemonium obovatum | Canine urine, CA | FR692000 |

| UTHSC 08-3696 | Phialemonium obovatum | Blood, TX | FR745949 |

| UTHSC 09-597 (2) | Phialemonium obovatum | Tissue, MN | FR692001 |

| UTHSC 09-845 | Phialemonium obovatum | Endocarditis, NC | FR691998 |

| UTHSC 09-1440 | Lecythophora sp. 3 | Respiratory, CA | |

| UTHSC 09-2358 | Phialemonium sp. 1 | Aspirate cellulitis, MA | |

| UTHSC R-3447 | Phialemonium curvatum | Eye, Israel | FR745927 |

| UTHSC R-3448 | Phialemonium curvatum | Eye, Israel | FR745931 |

| CBS 135.34 | Cephalotheca sulfurea | Garden cane, United Kingdom | AB189153c |

| CBS 140.41 | Lecythophora hoffmannii | Water pollution, United Kingdom | AF353600c |

| CBS 153.42T | Lecythophora decumbens | Fruit, Netherlands | |

| CBS 157.44T | Lecythophora mutabilis | River water, Germany | FR691990 |

| CBS 205.38T | Lecythophora fasciculata | Butter, Switzerland | FR691988 |

| CBS 206.38T | Lecythophora luteoviridis | Butter, Switzerland | FR691987 |

| CBS 206.73 | Lecythophora mutabilis | Aorta and mitral valve, USA | AB261979c |

| CBS 245.38T | Lecythophora hoffmannii | Butter, Switzerland | FR691982 |

| CBS 267.33T | Lecythophora lignicola | Sweden | FR691986 |

| CBS 279.76T | Phialemonium obovatum | Systemic infection, USA | FR691997 |

| CBS 457.88 | Albertiniella polyporicola | Ganoderma applanatum, Germany | AF096185c |

| CBS 491. 82T | Phialemonium dimorphosporum | Soil, USA | FR691976 |

| CBS 490.82T | Phialemonium curvatum | Skin lesion, USA | FR691977 |

| CBS 508.70T | Cryptendoxyla hypophloia | Wood, Canada | AB191032c |

| CBS 551.75 | Coniochaeta subcorticalis | Wood, Norway | AF353593c |

| CBS 730.97 | Phialemonium obovatum | Peritoneal dialysis fluid, USA | |

| CBS 109872T | Coniochaeta rhopalochaeta | Wood, Argentina | GQ351561c |

| CBS 110467 | Coniochaeta ligniaria | Wood, Germany | AF353583c |

| CBS 120874 | Coniochaeta velutina | Prunus salicina, South Africa | GQ154604c |

| CBS 120875T | Coniochaeta prunicola | Prunus armeniaca, South Africa | GQ1546031c |

| E. W. 95.605 | Coniochaeta ligniaria | Wood, Germany | AF353584c |

| HKUCC 2984 | Neolinocarpon globosicarpum | DQ810224c | |

| HKUCC 2954 | Linocarpon livistonae | DQ810206c | |

| HKUCC2983 | Neolinocarpon enshiense | DQ810221c | |

| NBRC 100905T | Cephalotheca foveolata | Subcutaneous infection, South Korea | AB178269c |

CBS, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, Netherlands; E. W., collection Evi Weber; HKUCC, University of Hong Kong Culture Collection; NBRC, NITE Biological Resource Center, Japan; UTHSC, Fungus Testing Laboratory, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. T, type strain. Numbers in parentheses represent isolate identification numbers of clinical samples.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Sequences retrieved from GenBank database.

Morphological study.

Morphological features of the isolates were examined on potato dextrose agar (PDA; Pronadisa, Madrid, Spain), oatmeal agar (OA; 30 g filtered oat flakes, 20 g agar, 1 liter distilled water), and water agar with sterilized plant material (small pieces of wood, filter paper, herbaceous leaves) to enhance the formation of ascomata (fruit bodies of the sexual state, or teleomorph) or conidiomata (fruit bodies of the asexual state, or anamorph). Cultures were incubated at room temperature (25°C ± 2°C) for up to 2 months. The isolates were identified using the criteria given by Damm et al. (6), De Hoog et al. (7), Gams and McGinnis (9), Weber (30), and Yaguchi et al. (34). Microscopic features were examined by making direct wet mounts with 85% lactic acid and lactophenol cotton blue, using light microscopy. Photomicrographs were obtained with a Zeiss Axio-Imager M1 light microscope, using phase contrast and Nomarski differential interference.

Sequencing and analysis.

Isolates were grown on yeast extract sucrose (YES; yeast extract, 2%; sucrose, 15%; agar, 2%; water, 1 liter) for 3 to 5 days at 25°C ± 2°C, and DNA was extracted using PrepMan Ultra sample preparation reagent (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The DNA was quantified by use of the GeneQuantpro calculator (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Cambridge, England). The D1/D2 domains of the 28S rDNA were amplified and sequenced with the primer pair NL1 and NL4, following the protocols described by Cano et al. (4). Sequences of clinical isolates were compared with those of type strains, when available, or reference strains, using the GeneDoc (version 2.6) program (17). A total of 84 sequences, including 15 GenBank sequences of species morphologically similar to some of the clinical isolates previously identified, were analyzed (Table 1). A sequence of Aureobasidium pullulans was used as the outgroup. Before this analysis, the sequences were aligned with the ClustalX (version 1.81) computer program (29), followed by manual adjustments with a text editor. The phylogenetic analyses were performed with the software program MEGA, version 4.0 (27). The neighbor-joining method and the Kimura two-parameter algorithm were used to obtain the distance tree. Gaps were treated as pair-wise deletions. Support for internal branches was assessed by a search of 1,000 bootstrapped sets of data.

Antifungal susceptibility.

We evaluated the in vitro activities of amphotericin B (AMB), anidulafungin (ANID), caspofungin (CAS), fluconazole (FLC), 5-fluorocytosine (5FC), itraconazole (ITC), micafungin (MICA), natamycin (NAT), posaconazole (PSC), terbinafine (TRB), and voriconazole (VRC) against 45 fungal isolates (Table 2) (5). Isolates were grown on PDA slants until they were mature. The inoculum turbidity was standardized spectrophotometrically (530 nm) to yield a final inoculum concentration of 0.4 × 104 to 5 × 104 CFU/ml. Tests were incubated at 35°C, with results being read at both 48- and 72-h endpoints. The MIC and minimum effective concentration (MEC) were defined as described by Perdomo et al. (18).

Table 2.

Results of in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing read at 48 and 72 h

| Species (no. of isolates) | Drug concn (μg/ml) read at 48/72 ha |

Drug concn (μg/ml) read at 48/72 ha |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB |

ITC |

PSC |

VRC |

TRB |

5-FC |

FLC |

NAT |

MICA |

ANID |

CAS |

||||||||||||

| MIC 50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MEC50 | MEC90 | MEC50 | MEC90 | MEC50 | MEC90 | |

| Phialemonium curvatum (12) | 1/2 | 2/4 | 0.5/0.5 | 8/1 | 0.06/0.25 | 1/0.5 | 0.25/0.5 | 2/2 | 0.25/1 | 1/1 | >64/— | >64/— | 8/8 | >64/64 | 4/4 | 8/8 | 0.5/1 | >8/— | 0.5/1 | >16/— | 2/>8 | >16/>8 |

| Phialemonium obovatum (14) | 16/>16 | >16/— | 1/1 | 1/2 | 0.5/1 | 1/2 | 0.25/1 | 1/2 | 0.06/0.06 | 0.125/0.125 | >64/— | >64/— | 8/16 | 16/32 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 0.03/0.125 | 0.125/0.125 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.5/0.5 |

| Lecythophora hoffmannii (8) | 0.5/1 | 0.5/2 | 0.25/0.5 | 1/0.5 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.5/1 | 0.5/1 | 0.5/1 | 0.06/0.25 | 0.25/0.5 | 64/>64 | >64/— | 8/16 | 8/16 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/>8 | >8/— | 2/>8 | >8/— | 2/2 | 4/>8 |

| Lecythophora mutabilis (5) | 0.125/0.25 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.25/1 | 0.25/1 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.125/0.5 | 2/>64 | 16/>64 | 8/16 | 8/16 | 4/4 | 4/4 | >8/— | >8/— | 2/>8 | >8/>8 | 4/>8 | 4/>8 |

| Cephalotheca foveolata (6) | 8/16 | 16/>16 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 2/2 | 0.06/0.25 | 0.25/0.5 | >64/— | >64/— | 8/16 | 64/32 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.5/0.5 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.5/0.25 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

—, no reading.

RESULTS

The 68 clinical isolates were morphologically identified, and their identities were molecularly confirmed to the genus level by a BLAST search. Of these, 32 belonged to Phialemonium, 20 to Lecythophora, 6 to Cephalotheca, 1 to Coniochaeta, 5 to Acremonium, and 4 to Phaeoacremonium. Isolates of the last two genera were excluded from the phylogenetic analysis.

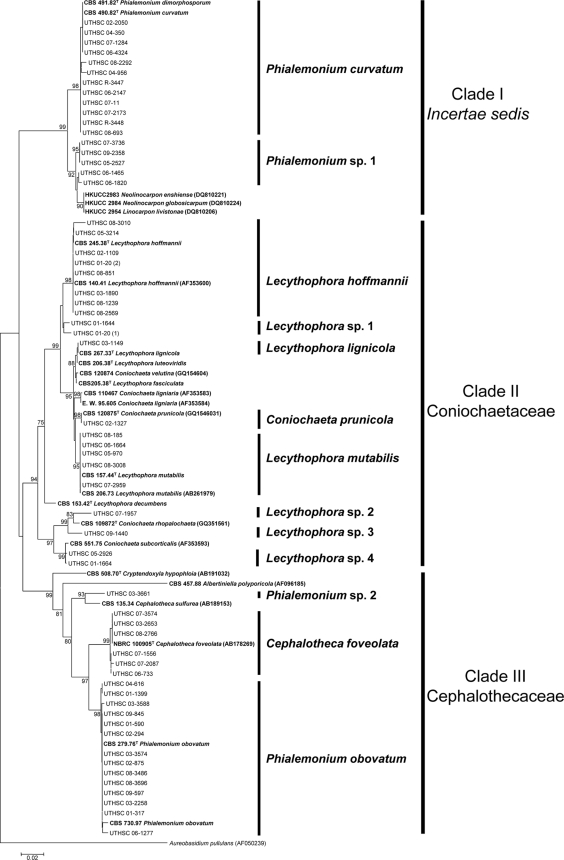

Figure 1 shows the neighbor-joining tree of the D1/D2 domains of 84 sequences, i.e., 59 belonging to the clinical isolates, 10 to type or reference strains, and 15 sequences retrieved from GenBank. The aligned sequence regions consisted of 452 bp. Three main clades (I to III), each supported by a high bootstrap value (bs), were observed in the phylogenetic tree.

Fig. 1.

Neighbor-joining tree among D1/D2 domains of the 28S rDNA sequences of the isolates included in Table 1. Branch lengths are proportional to distance. Sequences not generated in this study and obtained from the GenBank database are indicated in parentheses. Type and reference strains are indicated in boldface.

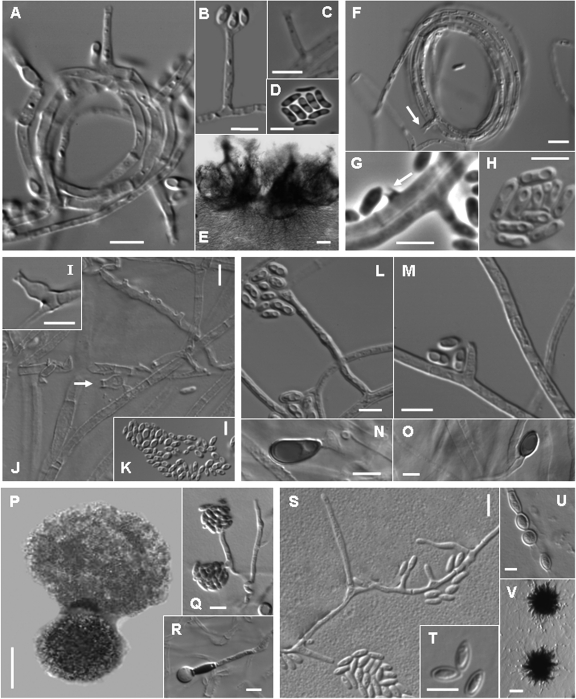

Clade I, divided into two subclades, included members of an uncertain higher taxonomic position (incertae sedis). In the first subclade (98% bs), 12 clinical isolates morphologically identified to be P. curvatum grouped with the type strains of P. curvatum (CBS 490.82) and P. dimorphosporum (CBS 491.82), which is considered a synonym. These fungi were characterized by smooth or finely floccose, white colonies becoming brown at maturity on OA, short and cylindrical adelophialides, and less commonly, long, tapering discrete phialides. Inconspicuous collarettes could be observed on both types of phialides (Fig. 2A to C). The conidia were hyaline and cylindrical to curved (Fig. 2D). Chlamydospores were not observed. Five of these isolates developed sporodochial conidiomata, which are cushion-shaped structures composed of well-differentiated, straight or flexuous, irregularly branched conidiophores, with stiff-haired setae forming a margin frill and with slimy conidia covering the entire upper surface of the conidioma (Fig. 2E). The second subclade (92% bs) included 5 Phialemonium sp. 1 clinical isolates morphologically similar to P. curvatum; however, on all culture media tested, they produced blackish, spherical, and closed conidiomata which opened irregularly in the apical part, liberating masses of conidia when they were mature. A BLAST search demonstrated a high degree of similarity of these fungi with the ascomycetes Linocarpon livistonae (GenBank accession number DQ810206), Neolinocarpon enshiense (GenBank accession number DQ810221), and Neolinocarpon globosicarpum (GenBank accession number DQ810224).

Fig. 2.

(A to E) Phialemonium curvatum (CBS 490.82T); (A) adelophialides; (B) conidia; (C) adelophialide with inconspicuous collarette; (D) conidia; (E) sporodochial conidioma. (F to H) Lecythophora hoffmannii (CBS 245.38T); (F) adelophialides with cylindrical collarettes in a hyphal coil; (G) collarette formed directly on the hyphae and conidia; (H) conidia. (I to K) Lecythophora lignicola (CBS 267.33T); (I) ventricose phialide; (J) adelophialide and discrete phialides; (K) conidia. (L to O) Lecythophora mutabilis (CBS 157.44T); (L) phialide; (M) adelophialide; (N and O) chlamydospores. (P to R) Cephalotheca foveolata (UTHSC 08-2766); (P) ascoma with ascospores; (Q) adelophialide and conidia; (R) chlamydospore. (S to V) Phialemonium obovatum (CBS 279.76T); (S) discrete phialides and adelophialides; (T) conidia; (U) chlamydospores; (V) inmature ascomata. Scale bars, A to D, F to O, and Q to U = 5 μm; V = 20 μm; E and P = 100 μm.

Clade II (94% bs) encompassed members of the family Coniochaetaceae, including species of Coniochaeta and Lecythophora and numerous clinical isolates. Eight clinical isolates and the type strain of L. hoffmannii (CBS 245.38) formed a well-supported terminal branch (98% bs). The most distinctive morphological features of these L. hoffmannii isolates were the production of slimy, orange to salmon-colored colonies on PDA, short adelophialides with cylindrical collarettes (Fig. 2F), and less frequently, discrete phialides with a wide base and a narrower apical part (ventricose phialides). Some collarettes were formed laterally, directly on the vegetative hyphae (Fig. 2G). The conidia were hyaline and broadly ellipsoidal to cylindrical or allantoid (Fig. 2H). Two clinical isolates (UTHSC 01-20 [sp. 1] and UTHSC 01-1644) were included in a close terminal branch identified as Lecythophora sp. 1. In another terminal branch, isolate UTHSC 03-1149 nested with the type strains of Lecythophora lignicola (CBS 267.33) and Lecythophora luteoviridis (CBS 206.38). This isolate showed 100% identity with the type strain of L. lignicola and was also morphologically very similar in producing discrete ventricose phialides with rather long collarettes (Fig. 2I to K) and lacking chlamydospores. Although L. luteoviridis also showed a close genetic relationship with L. lignicola, it differed from L. lignicola by developing globose, oblong or pear-shaped, and hyaline or faintly brown chlamydospores in young culture. In another terminal branch (98% bs), isolate UTHSC 02-1327 nested with a sequence of the type strain of the recently described ascomycete Coniochaeta prunicola (6). The clinical isolate was confirmed to be this species by development of ascomata on water agar with plant material and by development of similar conidial structures, including discrete ampulliform phialides, often constricted at the basal septum, and hyaline, mainly allantoid conidia.

Five clinical isolates were grouped with the type strain of L. mutabilis (CBS 157.44) in another terminal branch (95% bs). The most remarkable morphological feature of this group was the production of flat, moist, dark to olivaceous-brown colonies on OA, due to the presence of abundant chlamydospores, which are lateral or terminal, ovoidal to ellipsoidal, thick walled, olivaceous-brown, and never in chains (Fig. 2L to O). The basal subclade of clade II was represented by four clinical isolates (UTHSC 07-1957, UTHSC 09-1440, UTHSC 05-2926, and UTHSC 01-1664), plus sequences of Coniochaeta rhopalochaeta and C. subcorticalis. These clinical isolates, named Lecythophora sp. 2 to 4 in the tree, were morphologically heterogeneous, and their characteristics did not fit with those of any of the known Lecythophora species. Common morphological features observed among them were the production of dark colonies on OA and terminal or intercalary, pigmented chlamydospores forming short chains and the absence of ascomata.

Clade III (99% bs) included members of the family Cephalothecaceae. Clinical isolate UTHSC 03-3661, identified to be Phialemonium sp. 2, grouped with Cephalotheca sulfurea (93% bs), the type species of the genus Cephalotheca; however, ascomata were not produced in any of the culture media tested. All six clinical isolates which grouped with the type strain of C. foveolata in another subclade (99% bs) developed the teleomorph, characterized by blackish cleistothecial ascomata with a cephalothecoid wall (Fig. 2P), 8-spored asci, and ascospores that were broadly ellipsoidal to obovate in superficial view and reniform in lateral view with a foveolate wall. The anamorph was characterized by flat, moist, white to yellowish white (later becoming brownish) colonies on OA, with abundant adelophialides and less common discrete phialides, both with a wide base and without collarettes (Fig. 2Q). The conidia were cylindrical and hyaline. These isolates showed globose to ellipsoidal, thick-walled, hyaline, terminal, or intercalary chlamydospores (Fig. 2R). The third subclade (98% bs) included P. obovatum and 14 clinical isolates with the typical morphological features of the mentioned species. They were characterized by moist to slightly floccose and pale ochraceous to greenish colonies on OA. The adelophialides had a wide base, were more common than discrete phialides, and lacked visible collarettes (Fig. 2S). The conidia were hyaline and obovate with a truncate base (Fig. 2T). Oval, thin-walled, hyaline chlamydospores were also present (Fig. 2U). Most of these isolates, in old cultures, developed globose and dark structures which were suggestive of immature ascomata, although they never reached maturity (Fig. 2V).

In vitro antifungal susceptibility data varied between the various genera and species (Table 2). As there are no established guidelines for these genera, interpretive comments are based upon achievable serum concentrations using standard dosing regimens and are extrapolated from Candida breakpoints. As expected, all isolates displayed high MICs to 5FC and FLC. Phialemonium species and Cephalotheca foveolata appeared to be resistant to AMB. Most strains exhibited low MICs to PSC, VRC, and TRB, while only P. obovatum and C. foveolata demonstrated low MECs for the echinocandin agents MICA, ANID, and CAS. ITC data varied by species, and results for NAT, a topical ophthalmic polyene, are at the lower end of the range (2 to 32 μg/ml) typically seen for filamentous fungi (Fungus Testing Laboratory, unpublished data).

DISCUSSION

Some studies have clearly demonstrated the ability of Phialemonium and Lecythophora species to cause humans infections. However, the scarcity of case reports could be related to the misidentification of clinical isolates due to the morphological similarities of these fungi with other more common genera in human infections, such as Fusarium and Acremonium. The fact that 59 clinical isolates mainly belonging to Phialemonium and Lecythophora were received in a reference clinical center over the last 9 years showed that species of both genera are relatively common in clinical samples. However, the most recently published review of Phialemonium infections summarized only 20 cases of localized or disseminated infections that have been reported since 1986, of which 5 were caused by P. obovatum and 15 by P. curvatum (20). The number of clinical cases reporting infections by Lecythophora is even lower. Cases are caused by either L. hoffmannii or L. mutabilis (2, 7, 8, 16, 21, 22, 28). In our study, the above-mentioned two Phialemonium species and two Lecythophora species were also the predominant species identified. However, it is noteworthy that 6 isolates were identified to be C. foveolata, which is a recently described species involved in a case of human infection (25). Although we could not confirm the role of any of these C. foveolata isolates as agents of infection, the number found might reflect the possible clinical relevance of this fungus.

Our results confirmed the synonymy of P. dimorphosporum with P. curvatum (12) and that the two accepted species of Phialemonium, P. curvatum and P. obovatum, are genetically very distant from each other (34). Phialemonium obovatum, the type species of the genus, is more closely related to C. foveolata of the family Cephalothecaceae, while P. curvatum is molecularly related to some species of Linocarpon and Neolinocarpon, which are incertae sedis genera within Sordariomycetes (3).

A relevant feature not originally described in P. curvatum was the formation of sporodochial conidiomata, structures that were present in five clinical isolates. Other authors had already reported the presence of these structures (19, 24, 26, 32). Some isolates of Phialemonium (Phialemonium sp. 1) presented a relatively low level of similarity (97%) with the sequences of the type strain of P. curvatum. First, these isolates were identified to be P. curvatum due to the presence of adelophialides and the morphology of their conidia. In culture, they developed sporodochial conidiomata similar to those of P. curvatum, but a distinctive feature was the production of black, spherical, and closed conidiomata, so far never described in Phialemonium. Phialemonium sp. 1 was phylogenetically close to some species of the ascomycetous genera Linocarpon and Neolinocarpon, which have been associated with Phialophora-like anamorphs (3, 14). However, further studies are necessary to establish the real relationship between Phialemonium and those genera.

Our study showed the association of Lecythophora species with Coniochaeta, previously demonstrated by others (6, 10, 31). The two species of Lecythophora more common in clinical samples, L. hoffmannii and L. mutabilis, were strongly statistically supported. Although L. hoffmannii had been stated to be the anamorph of C. ligniaria (6, 7), our study confirmed the results of Weber et al. (31), who found that these species were different.

In conclusion, our results suggest that infections by Phialemonium, Lecythophora, and Cephalotheca may be underdiagnosed, since in this study the number of isolates belonging to these genera is considerably higher than that reflected in the literature. In addition, our results confirmed the usefulness of the 28S rDNA gene as a phylogenetic marker for these fungal groups.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to the curators of the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (Utrecht, Netherlands).

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, grants CGL 2008-04226/BOS and CGL 2009-08698/BOS.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 January 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abliz P., Fukushima K., Takizawa K., Nishimura K. 2004. Identification of pathogenic dematiaceous fungi and related taxa based on large subunit ribosomal DNA D1/D2 domain sequence analysis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 40:41–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahmad S., Johnson R. J., Hillier S., Shelton W. R., Rinaldi M. G. 1985. Fungal peritonitis caused by Lecythophora mutabilis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 22:182–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bahl J. 2006. Molecular evolution of three morphologically similar families in the Xylariomycetidae (Apiosporaceae, Clypeosphaeriaceae, Hyponectriaceae). Ph.D. thesis University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong: http://sunzi.lib.hku.hk/hkuto/agreement_form.jsp [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cano J., Guarro J., Gené J. 2004. Molecular and morphological identification of Colletotrichum species of clinical interest. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2450–2454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. Approved standard, 2nd ed. Document M38-A2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 6. Damm U., Fourie P. H., Crous P. 2010. Coniochaeta (Lecythophora), Collophora gen. nov. and Phaeomoniella species associated with wood necroses of Prunus trees. Persoonia 24:60–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Hoog G. S., Guarro J., Gené J., Figueras M. J. 2000. Atlas of clinical fungi, 2nd ed. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drees M., Wickes B. L., Gupta M., Hadley S. 2007. Lecythophora mutabilis prosthetic valve endocarditis in a diabetic patient. Med. Mycol. 45:463–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gams W., McGinnis M. 1983. Phialemonium, a new anamorph genus intermediate between Phialophora and Acremonium. Mycologia 75:977–987 [Google Scholar]

- 10. García D., et al. 2006. Molecular phylogeny of Coniochaetales. Mycol. Res. 110:1271–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gavin P. J., Sutton D. A., Katz B. Z. 2002. Fatal endocarditis in a neonate caused by the dematiaceous fungus Phialemonium obovatum: case report and review of the literature. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2207–2212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guarro J., et al. 1999. Phialemonium fungemia: two documented nosocomial cases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2493–2497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huhndorf S. M., Miller A. N., Fernandez F. A. 2004. Molecular systematics of the Sordariales: the order and the family Lasiosphaeriaceae redefined. Mycologia 96:368–387 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hyde K., Taylor J., Fröhlich J. 1998. Fungi from palms. XXXIV. The genus Neolinocarpon with five new species and one new combination. Fungal Diversity 1:115–131 [Google Scholar]

- 15. King D., Pasarell L., Dixon D. M., McGinnis M. R., Merz W. G. 1993. A phaeohyphomycotic cyst and peritonitis caused by Phialemonium species and a reevaluation of its taxonomy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1804–1810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marriott D. J., et al. 1997. Scytalidium dimidiatum and Lecythophora hoffmannii: unusual causes of fungal infections in a patient with AIDS. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2949–2952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nicholas K. B., Nicholas H. B., Jr., Deerfield D. W. I. I. 1997. GeneDoc: analysis and visualization of genetic variation. EMBnet News 4:1–4 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perdomo H., et al. 2010. Spectrum of clinically relevant Acremonium species in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:243–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Proia L. A., et al. 2004. Phialemonium: an emerging mold pathogen that caused 4 cases of hemodialysis-associated endovascular infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rivero M., et al. 2009. Infections due to Phialemonium species: case report and review. Med. Mycol. 47:766–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sakaeyama S., et al. 2007. Lecythophora hoffmannii isolated from a case of canine osteomyelitis in Japan. Med. Mycol. 45:267–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scott I. U., Cruz-Villegas V., Flynn H. W., Jr., Miller D. 2004. Delayed-onset, bleb-associated endophthalmitis caused by Lecythophora mutabilis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 137:583–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sigler L. 2003. Miscellaneous opportunistic fungi: Microascaceae and other ascomycetes, hyphomycetes, coelomycetes and basidiomycetes, p. 637–676 In Howard D. H. (ed.), Pathogenic fungi in humans and animals. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 24. Strahilevitz J., et al. 2005. An outbreak of Phialemonium infective endocarditis linked to intracavernous penile injections for the treatment of impotence. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:781–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suh M. K., et al. 2006. Subcutaneous hyalohyphomycosis due to Cephalotheca foveolata in an immunocompetent host. Br. J. Dermatol. 154:1184–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sutton D. A., et al. 2008. Pulmonary Phialemonium curvatum phaeohyphomycosis in a standard poodle dog. Med. Mycol. 46:355–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. 2007. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24:1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Taniguchi Y., et al. 2009. Septic shock induced by Lecythophora mutabilis in a patient with mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. J. Med. Microbiol. 58:1255–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D. G. 1997. The CLUSTAL X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4876–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weber E. 2002. The Lecythophora-Coniochaeta complex. I. Morphological studies on Lecythophora species isolated from Picea abies. Nova Hedwigia 74:159–185 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weber E., Görke C., Begerow D. 2002. The Lecythophora-Coniochaeta complex. II. Molecular studies based on sequences of the large subunit of ribosomal DNA. Nova Hedwigia 74:187–200 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weinberger M., et al. 2006. Isolated endogenous endophthalmitis due to a sporodochial-forming Phialemonium curvatum acquired through intracavernous autoinjections. Med. Mycol. 44:253–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wood C., Russel-Bell B. 1983. Characterization of pigmented fungi by melanin staining. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 5:77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yaguchi T., et al. 2006. A new Cephalotheca isolate from Korean patient. Mycotaxon 96:309–322 [Google Scholar]