Abstract

The advantages of using 2H2O to quantify cholesterol synthesis include i) homogeneous precursor labeling, ii) incorporation of 2H via multiple pathways, and iii) the ability to perform long-term studies in free-living subjects. However, there are two concerns. First, the t1/2 of tracer in body water presents a challenge when there is a need to acutely replicate measurements in the same subject. Second, assumptions are made regarding the number of hydrogens (n) that are incorporated during de novo synthesis. Our primary objective was to determine whether a step-based approach could be used to repeatedly study cholesterol synthesis a subject. We observed comparable changes in the 2H-labeling of plasma water and total plasma cholesterol in African-Green monkeys that received five oral doses of 2H2O, each dose separated by one week. Similar rates of cholesterol synthesis were estimated when comparing data in the group over the different weeks, but better reproducibility was observed when comparing replicate determinations of cholesterol synthesis in the same nonhuman primate during the respective dosing periods. Our secondary objective was to determine whether n depends on nutritional status in vivo; we observed n of ∼25 and ∼27 in mice fed a high-carbohydrate (HC) versus carbohydrate-free (CF) diet, respectively. We conclude that it is possible to acutely repeat studies of cholesterol synthesis using 2H2O and that n is relatively constant.

Keywords: stable isotopes, mass spectrometry, kinetic biomarker, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease

There are two general tracer approaches for quantifying lipid synthesis in vivo: either administer a carbon-labeled isotope (e.g., [14C] or [13C]acetate) or give labeled water (1, 2). Concerns generally surround the use of carbon-labeled tracers since one typically estimates the flux by determining a precursor/product labeling ratio. Questions arise regarding the identity of the true precursor labeling and the ability to correctly measure that value. In a classical study, Andersen and Dietschy demonstrated that different 14C-tracers yielded unique rates of hepatic cholesterol synthesis (2). Such discrepancies typically arise from heterogeneity of the underlying biochemistry. The administered tracer may not enter all cells or in the same proportion with other cholesterogenic substrates. This situation may result from various factors, including membrane permeability and activation/compartmentalization of substrates within a cell/organ, which can influence the dilution of the label and lead to uncertainty regarding the true precursor labeling.

Dietschy et al. demonstrated that labeled water is a preferred tracer for studying cholesterol synthesis (2–4). In addition to the fact that it enters all cells equally, labeled water allows investigators to perform integrative studies. For example, Taylor et al. administered 2H2O and quantified cholesterol synthesis in free-living humans over approximately 40 days, while rodent studies have been run for several months (5, 6). Although the last point represents a potentially important and novel advantage for labeled water, one of the perceived limitations concerns the t1/2 of the tracer in vivo. Because the t1/2 of 2H in body water may approach two weeks in humans, investigators may feel the need to allow approximately two months (or about four half-lives of the precursor labeling) to elapse before repeating a study in the same subjects. In addition, investigators typically assume that there is a constant number of exchangeable sites in a given product molecule. Namely, although 2H2O readily distributes in body water, 2H is incorporated into cholesterol via three distinct sources, including water, NADPH, and acetyl-CoA (7). When using 2H2O to quantify rates of synthesis, one assumes that the relative labeling of each hydrogen source is constant, which may be problematic in cases where building blocks are generated via multiple pathways (e.g., NADPH is made following glucose oxidation in the pentose pathway and/or by malic enzyme, whereas acetyl-CoA can be derived from glucose and/or fatty acid oxidation).

We previously demonstrated that one could administer 2H2O using a two-step strategy to study gluconeogenesis in rodents (8). For example, we quantified the contribution gluconeogenesis to glucose production by giving a low dose of 2H2O on one day and then repeated the study the following day by giving a higher dose. This approach allowed us to overcome the apparent limitation of the 2H2O method for measuring the source(s) of blood glucose in vivo (8).

The current study had two objectives. The first objective was to determine whether it was possible to use a step-based protocol to estimate cholesterol synthesis in vivo by using a nonhuman primate model in which cholesterol synthesis was estimated over five intervals. Our second objective was to examine a major assumption regarding the number of hydrogens (n) that are incorporated during cholesterol synthesis in vivo (9–11). As noted above, the hydrogen bound to cholesterol is derived from unique sources, two of which may be labeled to a different degree compared with body water. In this study, attention was directed toward determining whether n would remain constant under different nutritional states. These studies required the use of a rodent model, which has a faster metabolic rate and in which we could increase the precursor labeling to quantify the singly- and doubly-labeled mass isotopomers. Uncertainty concerning n is problematic in some settings (e.g., human and nonhuman primates) since one will typically only observe an increase in the abundance of singly-labeled product molecules (i.e., the M1 isotopomer); therefore, investigators are obligated to assume a value for n, unlike some experimental models (e.g., rodents and isolated organs or cells) in which multiple mass isotopomers can be quantified, and therefore, n can be calculated (9–12).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Unless noted, chemicals and reagents, including 99.8% 2H2O, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. [3-2H1]Cholesterol was purchased from Cambridge Isotopes (Andover, MA). African-Green monkeys were fed a commercial diet (5050 Purina Laboratory Fiber-Plus Monkey Diet). Rodent diets were purchased from Research Diets, Inc. (New Brunswick, NJ). All animal studies were approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Biological studies

Acutely replicating measurements of cholesterol synthesis in vivo.

African-Green monkeys (4.1 ± 0.3 kg, females) were individually housed and trained to drink from 30 ml syringes; ∼2 g of Prang (Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ) was added to the drinking water to encourage their training. Cholesterol synthesis was quantified over five weeks using the following protocol. On day 0 of a given week, a baseline blood sample (∼1 ml) was drawn, animals were then given an oral bolus of 2H2O (1.35 ml 2H2O × kg−1, i.e., ∼5 ml 2H2O) mixed in ∼18 ml of reverse osmosis water to which ∼2 g of Prang was added (to maintain the normal routine of the animal), although the animals were allowed to drink as they desired the tracer was typically ingested within 20 to 40 min. Blood samples (∼1 ml) were collected 24 and 48 h after the ingestion of 2H2O. This paradigm was repeated for five consecutive weeks, i.e., each week a baseline blood sample was drawn prior to the administration of 2H2O (1.35 ml 2H2O × kg−1, to which ∼2 g Prang was added) which was then followed by the collection of blood samples 24 and 48 h posttracer administration. Samples were collected in EDTA tubes and plasma was frozen until analyses. Note that throughout this study all animals were maintained on their normal feeding schedule and allowed access to ad libitum unlabeled water.

Determining the number of hydrogens incorporated during the synthesis of cholesterol in vivo.

Male C57BL/6J mice (11 weeks old) were randomized to either a high-carbohydrate, low-fat (HC) diet (D12450B, kcal distribution equal to 10% fat, 70% carbohydrate, and 20% protein) or a carbohydrate-free, high-fat (CF) diet (D12369B, 90% fat, 0% carbohydrate, and 10% protein). Mice in each group were fed the respective diets ad libitum for 13 days, all mice were then given an intraperitoneal injection of 99% 2H2O (20 μl × g−1 of body weight). After injection, mice were returned to their cages and maintained on 5% 2H-labeled drinking water. As previously demonstrated, this design will maintain a steady-state 2H-labeling of body water (9, 12, 13). Mice were euthanized after four days of 2H2O labeling, and plasma samples were frozen until analyses were performed.

Analytical

Water labeling.

The 2H-labeling of plasma water was determined as described by Shah et al. (14). Briefly, 2H present in water was exchanged with hydrogen bound to acetone by incubating 10 μl of plasma or known standards in a 2 ml glass screw-top GC vial at room temperature for 4 h with 2 μl 10N NaOH (Fisher Scientific) and 5 μl of acetone. The instrument was programmed to inject 5 μl of headspace gas from the GC vial in a splitless mode. Samples were analyzed using a 0.8 min isothermal run (Agilent 5973 MS coupled to a 6890 GC oven fitted with an Agilent DB-17 MS column, 15 m × 250 µm × 0.15 µm, the oven was set at 170°C, and the helium carrier flow was set at 1.0 ml × min−1), acetone elutes at ∼0.4 min; the mass spectrometer was set to perform selected ion monitoring of m/z 58 and 59 (10 ms dwell time per ion) in the electron impact ionization mode.

Cholesterol labeling: gas chromatography-pyrolysis-isotope ratio mass spectrometry.

5-α-Cholestane and 25-hydoxy-cholesterol (Steraloids, Newport, RI) were used as internal standards for cholesterol, and 25 μl 5-α-cholestane (2.8 mg × ml−1) and 35 μl (3.3 mg × ml−1) 25-hydoxy-cholesterol were added to the plasma samples prior to processing. Total (free plus bound) cholesterol was extracted as follows: 80 μl of plasma was saponified in 1N KOH at 60°C for 2 h, samples were cooled to room temperature and then extracted into 150 μl chloroform (JT Baker, Cambridge, MA) upon addition of 25 μl 6N HCl. The samples were then centrifuged for 5 min, and then the bottom layer (chloroform) was collected, evaporated to dryness, and reacted with 65 μl acetic anhydride/pyridine (2:1, v:v) at 75°C for 30 min before drying under a stream of N2. The dried residue was reconstituted in 90 μl ethyl acetate and subjected to gas chromatography-pyrolysis-isotope ratio mass spectrometry (GCpIRMS) analysis.

The 2H-labeling of cholesterol was determined using a Thermo Electron Isotope Ratio MS Delta V Plus (Bremen, Germany) coupled to Agilent 7890 Trace GC (San Jose, CA). Samples were analyzed using a splitless injection (1.5 μl injection volume at an inlet temperature of 230°C), the column (Agilent DB-5MS, 30 m × 250 um × 0.25 um) was programmed using a temperature gradient according to the following conditions: initial column temperature was set to 90°C with a 1 min hold followed by a ramp at 15°C per minute to 230°C, then ramped at 5°C per minute to 260°C and then ramped at 50°C per minute again to 330°C and held for 6 min. Compounds eluting off of the chromatographic column were directed into the pyrolysis reactor (heated at 1400°C) and converted to hydrogen gas, cholesterol elutes at ∼21 min.

Measured isotope ratios are typically expressed as delta (δ) values using the equation:

where δ is the fraction of heavy isotope represented in parts per thousand notation, Rref is the ratio of standard hydrogen gas, and Rsample is the ratio of the unknown sample. Since we aimed to determine cholesterol synthesis, it was necessary to compare the precursor/product labeling (see below). A standard curve was used to convert the delta values to enrichment (to compare with the water labeling, expressed as enrichment) by mixing known quantities of unlabeled cholesterol with known quantities of [3-2H1]cholesterol and analyzing in parallel with unknown samples.

Cholesterol labeling: gas chromatography-quadrupole-mass spectrometry.

Plasma samples for gas chromatography-quadrupole-mass spectrometry (GCqMS) analysis were processed in 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. An amount of 50 μl of plasma and 100 μl 1N KOH in 80% ethanol were heated at 65°C for 1 h. Samples were acidified with 25 μl 6N HCl and extracted in 125 μl chloroform followed by vigorous vortexing for 20 s The samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 min, and then 100 μl of chloroform (lower layer) was collected and evaporated to dryness under N2. Samples were derivatized using bis-trimethylsilyl trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) plus 10% trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS), 50 μl was added to the sample, and then it was incubated at 75°C for 1 h. Excess BSTFA-TMCS reagent was evaporated to dryness under N2. The trimethylsilyl derivative was reconstituted in 50 μl ethyl acetate for analysis by GC-MS.

Samples were analyzed by GCqMS using the Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph linked to an Agilent 5973 mass selective detector (Palo Alto, CA) operated at 70 eV, gas chromatography was performed using an Agilent DB-5MS capillary column (30.0 m × 250 um × 0.25 um), and 2 μl of sample was injected in a 20/1 split. The inlet temperature was set at 250°C and the helium gas carrier flow was set at 1 ml × min−1. The oven temperature was started at 150°C, raised at 20°C × min−1 to 310°C and held for 6 min. The mass spectrometer was set for selected ion monitoring of m/z 368, 369, and 370 for the trimethylsilyl cholesterol derivative with 10 ms dwell time per ion (15).

Mathematical modeling and calculations

In our studies, the water (or precursor) labeling was maintained at a pseudo steady-state during the initial 48 h immediately following the administration of each dose of 2H2O, while a fairly linear change in cholesterol (or product) labeling was observed over the same period. Therefore, the contribution of cholesterol synthesis was determined using the equation:

where the subscript refers to the time over which measurements were integrated each week and n is the number of exchangeable hydrogens (assumed to equal 26, see below). The absolute rate of cholesterol synthesis was determined by multiplying the % of newly made cholesterol by the average concentration of total plasma cholesterol measured during the respective 48 h interval.

Mass isotopomer analyses for determining the number of exchangeable hydrogens (n) in cholesterol.

The distribution of different mass isotopomers in a product molecule depends on the abundance of the isotopic precursor and the number of times the precursor is incorporated into a given product molecule (9, 10, 16–18). When 2H2O is used to quantify cholesterol synthesis, this can be represented by a binomial distribution where the variable is the ratio of hydrogen/deuterium. The ratio of doubly-to-singly-labeled isotopomers (i.e., the M2/M1 ratio) in cholesterol can be expressed as:

where n refers to the number of exchangeable hydrogens in a cholesterol molecule. Therefore, by measuring the M2/M1 labeling ratio of cholesterol and the labeling of body water, it is possible to solve the equation for n (9–12). These calculations were performed in mice given 2H2O.

Statistics.

Statistical tests were run for nonhuman primate data using ANOVA with Tukey's posthoc testing and unpaired t-tests for rodent studies. Unless noted, data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

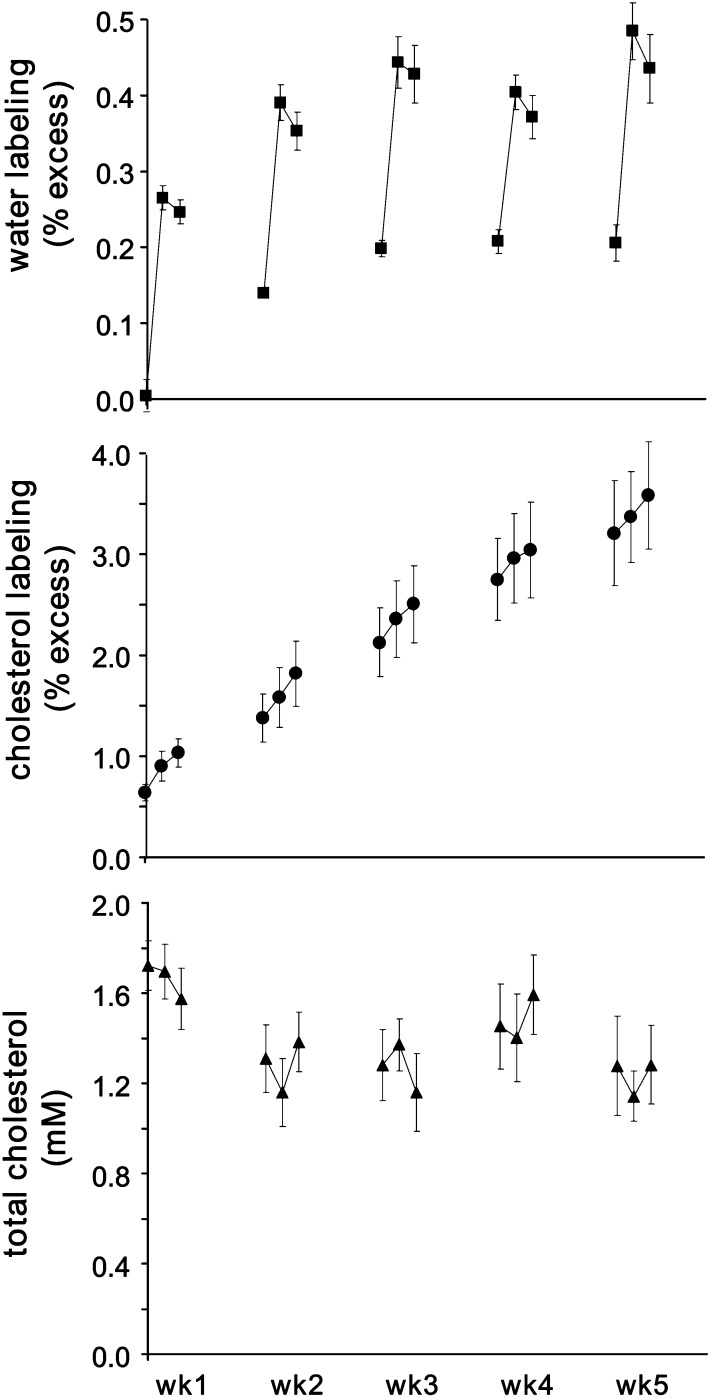

Figure 1 (top panel) demonstrates the time-dependent changes in 2H-labeling of the precursor during the course of the study. Based on the dose of tracer (1.35 ml 2H2O × kg−1), we expected an initial excess labeling of ∼0.23% (assuming ∼60% body water). As expected when giving a bolus of tracer, we observed a decrease in the labeling of body water between weeks 1 and 2. Since the subsequent doses of water were the same, each should have resulted in comparable changes in water labeling. Consistent with that logic, we observed comparable increases in the labeling of body water following the respective doses of 2H2O, with similar eliminations observed between the dosing periods. From the decreases in water labeling, we estimated that the t1/2 of water was equal to 6.2 ± 0.4 days, 6.1 ± 0.3 days, 5.1 ± 0.5 days, and 6.0 ± 0.7 days between weeks 1 and 2, weeks 2 and 3, weeks 3 and 4, and weeks 4 and 5, respectively.

Fig. 1.

2H-Labeling of body water and cholesterol and total plasma cholesterol concentration. Nonhuman primates were orally dosed with boluses of 2H2O over five consecutive weeks. The top panel demonstrates that there were comparable increases in the labeling of body water over the pre-existing background during each period, as well was a consistent elimination of 2H from body water between each period. The middle panel demonstrates that there were distinct and comparable increases in the 2H-labeling of total plasma cholesterol between the different experimental periods, determined using GCpIRMS. The bottom panel demonstrates that total plasma cholesterol concentration remained relatively stable over the experimental period. In all cases, data are mean ± SEM (n = 5).

Fig. 1 (middle panel) demonstrates the time-dependent changes in 2H-labeling of total plasma cholesterol. As expected, there was a sharp increase in the labeling of cholesterol during the 48 h immediately after each dosing with 2H2O, and the labeling tended to plateau between weekly intervals as expected, since the water labeling was decreasing (Fig. 1, top panel). However, note that there appears to be substantial 2H-labeling in the initial sample (i.e., ∼0.5% 2H-labeling compared with theoretical 2H-labeling of ∼0.02%), due to the fact that these animals had been used in a pilot tracer study prior to this experiment. We assumed that this seemingly exaggerated baseline cholesterol labeling did not impact the results of the current study. Rather, this observation emphasized the need to obtain baseline samples to account for differences in the measured versus the expected isotope labeling ratios.

Fig. 1 (bottom panel) demonstrates the concentration of total plasma cholesterol over the time course of the study. A reasonable steady-state was achieved as expected as animals were maintained in the same environment.

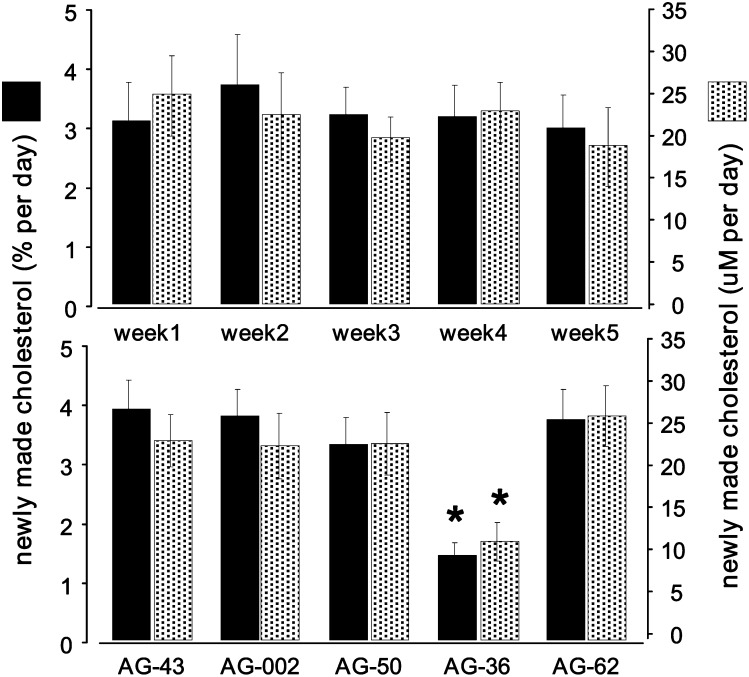

Fig. 2 demonstrates cholesterol kinetics calculated from the 2H-labeling and plasma concentrations. The top panel demonstrates the group averages over a given week, while the bottom panel demonstrates the averages in a given animal over the five weeks. In both cases, the data are expressed as the percentage contribution of de novo synthesis (solid bars) and the absolute amount of newly made cholesterol (shaded bars). Although the data are relatively reproducible over the various periods (top panel), the coefficient of variation is reduced by ∼50% when individual animals are studied (bottom panel); i.e., ∼20-25% in the top panel versus ∼12-15% in the bottom panel. The bottom panel demonstrates that although there is variation across individual animals, results in given subjects are fairly reproducible.

Fig. 2.

Calculated rates of cholesterol synthesis. 2H-labeling data were used to estimate cholesterol synthesis. Data are expressed as the percent of newly made cholesterol (solid bars) and the absolute amount of newly made cholesterol (shaded bars). The top panel demonstrates the weekly estimates of cholesterol synthesis showing the collective data from the group, while the bottom panel demonstrates cholesterol synthesis in a given animal measured over five weeks. In all cases, data are mean ± SEM (n = 5); *P < 0.05.

The mass isotopomer distribution of cholesterol obtained from mice fed a high-carbohydrate or a carbohydrate-free diet is presented in Table 1. The baseline samples obtained from control mice demonstrate that quadrupole-based mass spectrometers are capable of measuring isotopic labeling with a relatively high degree of precision (the coefficient of variation is less than 0.5%) and that the experimentally measured values closely agree with theoretical values. Spectra were corrected for natural background labeling, and the excess M1 and M2 isotopomers were used to calculate n. Note that this calculation requires an estimate of the water labeling (i.e., the precursor or p), which was approximately what we expected based on the experimental design (i.e., ∼2.9%). The estimated value for n was comparable in the different diet groups.

TABLE 1.

Estimated Number of Exchangeable Hydrogens in Cholesterol

| Cholesterol Isotopomer Distribution (%) |

||||

| Group | M1 | M2 | Water Labeling (% Excess) | n |

| Theoretical | 29.9 | 4.4 | — | — |

| Control | 30.2 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | — | — |

| CF diet | 48.4 ± 2.4 | 17.0 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 27.0 ± 1.0 |

| HC diet | 39.8 ± 2.0 | 10.8 ± 1.4 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 25.2 ± 1.0 |

The mass isotopomer profile of cholesterol and the labeling of plasma water were determined using GCqMS. The theoretical isotope distribution profile for cholesterol was determined using the isotope calculator reported at http://www.sisweb.com/mstools/isotope.htm. In all cases, the abundance of the M0 isotopomer of cholesterol is 100% (data not shown), and the abundance of the M1 and M2 isotopomers of cholesterol are expressed as a percentage of M0. The number of exchangeable hydrogens (n) was determined from the M2/M1 labeling ratio of cholesterol. Water labeling was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data are mean ± SEM (five mice per group).

DISCUSSION

The use of isotope tracers in metabolic research is complicated by physiological constraints that influence the quality of the data. Definitive interpretations regarding biochemical flux may elude investigators as issues regarding the true precursor labeling may not be fully understood and multiple pathways may contribute to the synthesis of a product (1). For example, Zhang et al. probed the labeling of extra-mitochondrial acetyl-CoA by perfusing isolated rat livers with several [13C]tracers in the presence of drugs that undergo acetylation (note that the labeling of the acetyl moiety of the drug conjugates provided a “chemical biopsy” of intracellular acetyl-CoA labeling) (19). In most cases, the different tracers and xenobiotic probes yielded different enrichments, suggesting a zonation of acetyl-CoA labeling (19). Those observations support and expand the seminal studies of Andersen and Dietschy (2). Using conscious dogs, Puchowicz et al. observed transhepatic concentration and labeling gradients of [13C]acetate (∼3-fold and ∼7-fold, respectively), which suggested the existence of multiple pools of hepatic acetyl-CoA (20). Despite the fact that these studies imply a limited usefulness for carbon-labeled precursors (e.g., [13C]acetate), Kelleher et al. have devised an elegant approach that can account for heterogeneity (21–24), with the caveat that a substantial labeling of the precursor pool is required to generate multiple mass isotopomer species in the products.

Although the examples noted above suggest a limited usefulness for carbon-labeled tracers in studies of cholesterol synthesis, one needs to consider that different physiological scenarios have been used. For example, several of the experiments focused on animal models; therefore, the data may not translate entirely in humans. Di Buono et al. simultaneously compared [13C]acetate and 2H2O in the same human subjects (25); a low dose of 2H2O was given and the 2H-labeling of cholesterol was determined using isotope ratio mass spectrometry and compared against the 2H-labeling of body water, while a high dose of [13C]acetate was given and mass isotopomer distribution analysis was used to estimate the precursor labeling and the contribution of newly made cholesterol. Their data suggested that both methods yield comparable results when studies are extended to ∼24 h, suggesting that issues regarding precursor/product labeling ratios may be less problematic in some instances (25). However, when Di Buono et al. compared the two methods in their originally proposed forms (i.e., ∼15 h for the infusion of [13C]acetate versus ∼24 h of exposure to 2H2O), they observed a significant difference between the apparent contribution of de novo cholesterol synthesis estimated using the different methods. The latter observation raises an important question regarding “metabolic stability” over the course of a study in subjects who are confined to a metabolic research unit versus the use of an integrative design that would account for normal lifestyle patterns. Since 2H2O it typically given orally and since body water has a relatively long t1/2, it is possible to run studies over several weeks and therein measure kinetic parameters over extended periods of time. Taylor et al. capitalized on these advantages of labeled water and quantified cholesterol synthesis in free-living humans over the course of ∼40 days (6). In addition, since cholesterol synthesis appears to follow a circadian rhythm over the course of a day (26), the ability to conduct studies that span variable periods may be of particular importance if the amplitude and/or the frequency of the oscillations in cholesterol synthesis change with health status, dyslipidemia, and/or therapeutic intervention.

We have considered two essential (and seemingly negative) issues regarding the use of labeled water in studies of cholesterol synthesis. First, since body water has a relatively long t1/2, investigators may feel the need to allow multiple half-lives to elapse to eliminate the precursor labeling between studies. As we have demonstrated, although the t1/2 of water approached one week in nonhuman primates, we were able to administer multiple doses of 2H2O and estimate cholesterol synthesis over several weeks. The excess water labeling that was observed at the end of week 1 (prior to giving a second dose of 2H2O in week 2) simply set the second week of the protocol at a higher starting point (Fig. 1, top panel). Namely, instead of giving a dose of 2H2O over a natural background labeling of ∼0.02% 2H (week 1), the second week of our protocol started at a background water labeling of ∼0.12% 2H. Likewise, the initial cholesterol labeling was higher at the start of the second week (Fig. 1, middle panel). Clearly, we observed substantial and comparable increases in the labeling of water and cholesterol between the subsequent weeks (Fig. 1, top and middle panels). We estimated that de novo cholesterol synthesis contributed ∼3% per day across the various weeks in the entire group (Fig. 2, top panel). However, the ability to readily repeat measurements within a given animal demonstrated consistency between most of the animals, with one (AG-36) being much lower (Fig. 2, bottom panel).

The current studies on cholesterol synthesis are similar to our previous work in which we demonstrated the ability to administer consecutive doses of 2H2O and quantify gluconeogenesis (8). Namely, we were able to dose 2H2O on back-to-back days and therein estimate the contribution of gluconeogenesis to total glucose production in vivo. The ability to acutely replicate studies largely depends on measurements of small changes in isotopic labeling. In our previous study, we capitalized on a novel means of processing the gas chromatography-(quadrupole) mass spectrometry data, whereas in the current study we relied on the use of gas chromatography-pyrolysis-isotope ratio mass spectrometry (8). Presumably, we could have shortened the time between dosing regimens in the current study; however, there were practical constraints that affected the design. Most notably, since the nonhuman primate model was in the early stage of development, we were only able to obtain samples according to the described protocol. On the basis of the extensive work by Jones et al., we expect that more frequent sampling will yield novel insight regarding the regulation of cholesterol dynamics (25, 26). In addition, more frequent sampling should improve confidence in the data fitting. Obviously, fitting curves with a minimum of data points is desirable, and future studies will likely address how the number of data points and the timing of their collection impact the estimated biochemical parameters.

The second major issue regarding the use of labeled water in studies of cholesterol synthesis centers on the number of hydrogens (deuteriums) that are incorporated during the synthesis of a new molecule. This value is often referred to as the n (9–12). Namely, when administering low doses of 2H2O, one will typically only observe the production of singly-labeled product molecules; therefore, investigators assume that the relative source(s) of hydrogen (or deuterium) does not change during the course of the study (1). For example, one will typically estimate the rate of synthesis from the change in the M1/M0 labeling of cholesterol relative to the labeling in body water multiplied by a constant that accounts for the incorporation of hydrogen (n) (27–31). There are at least three direct approaches for determining the n for cholesterol and/or for evaluating the stability of n. These include i) utilizing a doubly-labeled approach (i.e., simultaneously administering carbon-labeled tracers with labeled water), ii) relying on a mathematical approach (i.e., giving a relatively large amount of 2H2O and estimating n from the mass isotopomer distribution of cholesterol), and iii) feeding a cholesterol-free diet and estimating the asymptotic labeling of cholesterol relative to body water labeling. A final, albeit indirect, approach for estimating the stability of n would be to evaluate a different end-product constructed from the same starting materials (e.g., the synthesis of palmitate and cholesterol each requires acetyl-CoA, NADPH, and water).

We reviewed the literature regarding the use of labeled water in studies of lipid synthesis (Table 2). In some cases, investigators simultaneously determined the n for palmitate and cholesterol, whereas other investigators limited their attention to a single end-product. As well, some studies were performed under relatively acute conditions with minimal chances of tracer recycling (e.g., incubating adipose tissue with unlabeled glucose), while other studies involved highly integrative designs (e.g., 2H2O was administered over several days in vivo). In spite of the striking differences in experimental protocols, the contribution of hydrogen labeling to palmitate remained remarkably constant. In a variety of in vivo and in vitro models, ∼22 hydrogens were incorporated per mol of newly made palmitate. Likewise, in studies of cholesterol synthesis, the number of hydrogens incorporated per mol of newly made material was also generally constant at ∼25. Obviously, the absolute values for the n observed in palmitate and cholesterol are likely to be different since the respective molecules contain different amounts of hydrogen. As well, one expects some variation between the studies as i) different analytical methods were used by investigators, ii) a broad range of models was examined, and iii) various approaches were used to estimate n.

TABLE 2.

Incorporation of Hydrogen (Deuterium) During Lipid Synthesis

| Incorporation of Label per Newly Made Molecule |

|||

| Reference | Condition | Palmitate | Cholesterol |

| (44) | Isolated adipose tissue | ∼23 | ND |

| (45) | Isolated perfused livers | ∼22 | ND |

| (9) | Sprague-Dawley rats in vivo (∼80-104 h) | ∼20-23 | ∼26-28 |

| (12) | HRS hairless mice in vivo (∼5 days) | ∼20-24 m2/m1 | ND |

| ∼22-24 m3/m2 | |||

| (11) | Hep G2 and MCA cells | ∼16-18 | ∼18-21 |

| (10) | Sprague-Dawley rats in vivo (∼1-8 weeks) | ∼22-23 (liver) | ∼30-31 (liver) |

| ∼20-22 (brain, cord, nerve) | ∼25-29 (brain, cord, nerve) | ||

| (46) | Chinese hamster ovary cells | ND | ∼22 |

| (47) | Human fibroblasts, Hep G2 cells | ND | ∼20, ∼25 |

| (48) | Mice in vivo (∼98 days) | ND | ∼23 |

| (3) | Rodents in vivo | ND | ∼21-24 |

| Perfused organs, cultured cells in vitro | ND | ∼22-27 | |

| (7) | Sprague-Dawley rats in vivo (∼2 h) | ND | ∼22 |

Palmitate and cholesterol are typically made from the same precursor units (i.e., water, NADPH, and acetyl-CoA), although the absolute contribution of the different hydrogen sources varies. Different approaches were used to estimate the number of deuterium atoms incorporated per lipid molecule.

ND, not determined.

To expand on the literature, we performed a study in C57BL/6J mice fed either a high-carbohydrate or a carbohydrate-free diet. We expected that these extreme nutritional manipulations would dramatically influence the source of precursors that are used to synthesize cholesterol. For example, we previously used this type of dietary intervention to address questions regarding the source(s) of carbon flux into triglycerides in mice (32). Consistent with what one might predict, we previously observed that there was less 2H-labeling in blood glucose when animals consumed a substantial amount of calories as carbohydrate versus extensive 2H-labeling of glucose when animals consumed a CF diet. Conversely, the HC diet led to extensive labeling of triglyceride-bound palmitate whereas the CF diet led to negligible labeling of triglyceride-bound palmitate (32). Therefore, if we consider that shifts in glucose versus fatty acid oxidation influence the source(s) of precursor labeling, then the dietary intervention used in our rodent study approached the extremes in terms of manipulating the precursor labeling. Surprisingly, we observed a comparable value for n in both diet groups (Table 1), and the values that we obtained (i.e., ∼26) are in agreement with the literature. Thus, we believe that n is expected to be constant under most conditions; the exception would likely be in cases where cholesterol is made from precursors that bypass the acetyl-CoA pool (e.g., conversion of mevalonate to cholesterol) and/or require the utilization of less NADPH (e.g., conversion of squalene to cholesterol).

We expect that future studies can use the logic described herein, perhaps with some additional modifications. For example, it should be possible to compress the time scale between dosing intervals and/or it should be possible to repeat this paradigm and include additional dosing intervals. The only caveat to these modifications concerns the apparent toxicity of 2H2O (33, 34). The levels of 2H-labeling that are associated with toxicity are much greater than those typically used in tracer studies (e.g., ∼25% 2H-labeling in body water is harmful if maintained for several weeks, whereas our studies in humans and nonhuman primates used less than ∼0.5%). Although our rodent studies typically used ∼2.5% 2H-labeling in body water, that value also appears to be reasonable considering the literature (35). Lastly, the acute ingestion of 2H2O, even in relatively small quantities (i.e., sufficient to enrich body water to ∼0.5% in humans), is associated with the transient side-effects of nausea and vertigo (6, 36); presumably these were minimized (in the nonhuman primates) by diluting the tracer in water and allowing the monkeys to slowly ingest the required dose.

We conclude with a few remarks regarding the choice of the model and why we believe that the ability to readily perform replicate measurements in the same subjects should be advantageous. First, although a substantial amount of new knowledge regarding lipid biology can be derived from studies in rodents, the lipoprotein profiles of mice are generally dramatically different from those observed in humans (37–39). In that regard, nonhuman primates are an important resource for understanding the basic science surrounding dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis (40–42). Second, considering the potential for differences between the biology in individual animals, one would likely expect greater variation in baseline parameters and/or sensitivity to treatments (unlike most rodent models, nonhuman primates are typically not inbred). As we have demonstrated, because subjects can be studied as their own controls, we expect that it is now possible to minimize some of the noise that might be observed when examining interventions (e.g., treatment with a “statin”). Third, by running studies over longer intervals, one could presumably account for variability of the underlying metabolism. Namely, if changes in a subject's routine alter cholesterol synthesis and/or circadian rhythms (26, 43), a person's baseline cholesterol synthesis might vary if/when it was measured over a short interval. Lastly, the ability to readily repeat studies should allow clinical investigators to screen subjects and/or more frequently monitor a subject regarding the efficacy of target engagement once (s)he is prescribed a medication.

APPENDIX

The incorporation of isotope tracers into end-products can be modeled using different approaches and experimental designs. For example, one can use a constant infusion of a tracer or administer a single bolus of a tracer; likewise, one can use steady-state or non steady-state treatments of the data. In the current study, we have considered the use of a steady-state approach; however, one could integrate measurements of precursor product labeling over various periods of time. For purposes of the current study, we chose to model the data in a rather simple mathematical form during the initial pseudo steady-state phase of 2H-labeling in each period. We briefly considered a more general solution that would be applicable if samples are obtained over longer periods of time.

Assuming the following reactions:

where H2O and cholesterol are abundant in the time scale of the investigation, then 2H2O and [2H]cholesterol are the two rate-limiting factors. In addition, assuming that once 2H is incorporated into cholesterol, the label does not come off back to water and that [2H]cholesterol is converted into other molecules, one can develop a general solution to the problem and solve for cholesterol synthesis. Namely, letting x and y represent 2H2O and [2H]cholesterol, the equations describing the dynamics of the reaction are:

where u(t) is the derivative of input bolus and k, k′, and k′′ represent the elimination of labeled water, the synthesis of cholesterol, and the removal of cholesterol, respectively.

We recognize that investigators will use different experimental designs to best address their hypotheses, and we expect that the logic outlined in this report can be customized to fit the specific needs of a given study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marcie Donnelly, Cesaire Gai, and Andrew Gewain for their expertise in handling and training the African Green monkeys used in these studies.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- CF

- carbohydrate-free, high-fat

- GCpIRMS

- gas chromatography-pyrolysis-isotope ratio mass spectrometry

- GCqMS

- gas chromatography-quadrupole-mass spectrometry

- HC

- high-carbohydrate, low-fat

REFERENCES

- 1.Casazza J. P., Veech R. L. 1984. Quantitation of the rate of fatty acid synthesis. Lab. Res. Methods Biol. Med. 10: 231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen J. M., Dietschy J. M. 1979. Absolute rates of cholesterol synthesis in extrahepatic tissues measured with 3H-labeled water and 14C-labeled substrates. J. Lipid Res. 20: 740–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dietschy J. M., Spady D. K. 1984. Measurement of rates of cholesterol synthesis using tritiated water. J. Lipid Res. 25: 1469–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowenstein J. M., Brunengraber H., Wadke M. 1975. Measurement of rates of lipogenesis with deuterated and tritiated water. Methods Enzymol. 35: 279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng S. K., Ho K. J., Mikkelson B., Taylor C. B. 1973. Studies on cholesterol metabolism in rats by application of D2O and mass spectrometry. Atherosclerosis. 18: 197–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor C. B., Mikkelson B., Anderson J. A., Forman D. T. 1966. Human serum cholesterol synthesis measured with the deuterium label. Arch Path. 81: 213–231. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakshmanan M. R., Veech R. L. 1977. Measurement of rate of rat-liver sterol synthesis invivo using tritiated-water. J. Biol. Chem. 252: 4667–4673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katanik J., Mccabe B. J., Brunengraber D. Z., Chandramouli V., Nishiyama F. J., Anderson V. E., Previs S. F. 2003. Measuring gluconeogenesis using a low dose of 2H2O: advantage of isotope fractionation during gas chromatography. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 284: E1043–E1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diraison F., Pachiaudi C., Beylot M. 1996. In vivo measurement of plasma cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis with deuterated water: determination of the average number of deuterium atoms incorporated. Metabolism. 45: 817–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee W. N., Bassilian S., Ajie H. O., Schoeller D. A., Edmond J., Bergner E. A., Byerley L. O. 1994. In vivo measurement of fatty acids and cholesterol synthesis using D2O and mass isotopomer analysis. Am. J. Physiol. 266: E699–E708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee W. N., Bassilian S., Guo Z., Schoeller D., Edmond J., Bergner E. A., Byerley L. O. 1994. Measurement of fractional lipid synthesis using deuterated water (2H2O) and mass isotopomer analysis. Am. J. Physiol. 266: E372–E383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ajie H. O., Connor M. J., Lee W. N., Bassilian S., Bergner E. A., Byerley L. O. 1995. In vivo study of the biosynthesis of long-chain fatty acids using deuterated water. Am. J. Physiol. 269: E247–E252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunengraber D. Z., Mccabe B. J., Kasumov T., Alexander J. C., Chandramouli V., Previs S. F. 2003. Influence of diet on the modeling of adipose tissue triglycerides during growth. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 285: E917–E925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah V., Herath K., Previs S. F., Hubbard B. K., Roddy T. P. 2010. Headspace analyses of acetone: a rapid method for measuring the 2H-labeling of water. Anal. Biochem. 404: 235–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasturi S., Bederman I. R., Christopher B., Previs S. F., Ismail-Beigi F. 2007. Exposure to azide markedly decreases the abundance of mRNAs encoding cholesterol synthetic enzymes and inhibits cholesterol synthesis. J. Cell. Biochem. 100: 1034–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strong J. M., Upton D. K., Anderson L. W., Monks A., Chisena C. A., Cysyk R. L. 1985. A novel approach to the analysis of mass spectrally assayed stable isotope-labeling experiments. J. Biol. Chem. 260: 4276–4281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hellerstein M. K., Neese R. A. 1999. Mass isotopomer distribution analysis at eight years: theoretical, analytic, and experimental considerations. Am. J. Physiol. 276: E1146–E1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunengraber H., Kelleher J. K., Des R. C. 1997. Applications of mass isotopomer analysis to nutrition research. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 17: 559–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y., Agarwal K. C., Beylot M., Soloviev M. V., David F., Reider M. W., Anderson V. E., Tserng K. Y., Brunengraber H. 1994. Nonhomogeneous labeling of liver extra-mitochondrial acetyl-CoA. Implications for the probing of lipogenic acetyl-CoA via drug acetylation and for the production of acetate by the liver. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 11025–11029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puchowicz M. A., Bederman I. R., Comte B., Yang D., David F., Stone E., Jabbour K., Wasserman D. H., Brunengraber H. 1999. Zonation of acetate labeling across the liver: implications for studies of lipogenesis by MIDA. Am. J. Physiol. 277: E1022–E1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bederman I. R., Kasumov T., Reszko A. E., David F., Brunengraber H., Kelleher J. K. 2004. In vitro modeling of fatty acid synthesis under conditions simulating the zonation of lipogenic [13C]acetyl-CoA enrichment in the liver. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 43217–43226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bederman I. R., Reszko A. E., Kasumov T., David F., Wasserman D. H., Kelleher J. K., Brunengraber H. 2004. Zonation of labeling of lipogenic acetyl-CoA across the liver: implications for studies of lipogenesis by mass isotopomer analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 43207–43216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelleher J. K., Kharroubi A. T., Aldaghlas T. A., Shambat I. B., Kennedy K. A., Holleran A. L., Masterson T. M. 1994. Isotopomer spectral analysis of cholesterol synthesis: applications in human hepatoma cells. Am. J. Physiol. 266: E384–E395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelleher J. K., Masterson T. M. 1992. Model equations for condensation biosynthesis using stable isotopes and radioisotopes. Am. J. Physiol. 262: E118–E125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Buono M., Jones P. J., Beaumier L., Wykes L. J. 2000. Comparison of deuterium incorporation and mass isotopomer distribution analysis for measurement of human cholesterol biosynthesis. J. Lipid Res. 41: 1516–1523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones P. J., Schoeller D. A. 1990. Evidence for diurnal periodicity in human cholesterol synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 31: 667–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones P. J. 1996. Tracing lipogenesis in humans using deuterated water. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 74: 755–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones P. J. 1990. Use of deuterated water for measurement of short-term cholesterol synthesis in humans. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 68: 955–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leitch C. A., Jones P. J. 1993. Measurement of human lipogenesis using deuterium incorporation. J. Lipid Res. 34: 157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leitch C. A., Jones P. J. 1991. Measurement of triglyceride synthesis in humans using deuterium oxide and isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Biol. Mass Spectrom. 20: 392–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diraison F., Pachiaudi C., Beylot M. 1997. Measuring lipogenesis and cholesterol synthesis in humans with deuterated water: use of simple gas chromatographic/mass spectrometric techniques. J. Mass Spectrom. 32: 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bederman I. R., Foy S., Chandramouli V., Alexander J. C., Previs S. F. 2009. Triglyceride synthesis in epididymal adipose tissue: contribution of glucose and non-glucose carbon sources. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 6101–6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Czajka D. M., Finkel A. J., Fischer C. S., Katz J. J. 1961. Physiological effects of deuterium on dogs. Am. J. Physiol. 201: 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katz J. J., Crespi H. L., Czajka D. M., Finkel A. J. 1962. Course of deuteriation and some physiological effects of deuterium in mice. Am. J. Physiol. 203: 907–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng S. K., Ho K. J., Taylor C. B. 1972. Biologic effects of prolonged exposure to deuterium oxide. A behavioral, metabolic, and morphologic study. Arch. Pathol. 94: 81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Previs S. F., Fatica R., Chandramouli V., Alexander J. C., Brunengraber H., Landau B. R. 2004. Quantifying rates of protein synthesis in humans by use of 2H2O: application to patients with end-stage renal disease. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 286: E665–E672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plump A. S., Breslow J. L. 1995. Apolipoprotein E and the apolipoprotein E-deficient mouse. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 15: 495–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kieft K. A., Bocan T. M., Krause B. R. 1991. Rapid on-line determination of cholesterol distribution among plasma lipoproteins after high-performance gel filtration chromatography. J. Lipid Res. 32: 859–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiao S., Cole T. G., Kitchens R. T., Pfleger B., Schonfeld G. 1990. Genetic heterogeneity of plasma lipoproteins in the mouse: control of low density lipoprotein particle sizes by genetic factors. J. Lipid Res. 31: 467–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cefalu W. T., Wagner J. D., Bell-Farrow A. D., Edwards I. J., Terry J. G., Weindruch R., Kemnitz J. W. 1999. Influence of caloric restriction on the development of atherosclerosis in nonhuman primates: progress to date. Toxicol. Sci. 52: 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki M., Yamamoto D., Suzuki T., Fujii M., Suzuki N., Fujishiro M., Sakurai T., Yamada K. 2006. Effect of fructose-rich high-fat diet on glucose sensitivity and atherosclerosis in nonhuman primate. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 28: 609–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagner J. E., Kavanagh K., Ward G. M., Auerbach B. J., Harwood H. J., Jr, Kaplan J. R. 2006. Old world nonhuman primate models of type 2 diabetes mellitus. ILAR J. 47: 259–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones P. J., Scanu A. M., Schoeller D. A. 1988. Plasma cholesterol synthesis using deuterated water in humans: effect of short-term food restriction. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 111: 627–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jungas R. L. 1968. Fatty acid synthesis in adipose tissue incubated in tritiated water. Biochemistry. 7: 3708–3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wadke M., Brunengraber H., Lowenstein J. M., Dolhun J. J., Arsenault G. P. 1973. Fatty acid synthesis by liver perfused with deuterated and tritiated water. Biochemistry. 12: 2619–2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Esterman A. L., Cohen B. I., Javitt N. B. 1985. Cholesterol metabolism: use of D2O for determination of synthesis rate in cell culture. J. Lipid Res. 26: 950–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Javitt N. B., Javitt J. I. 1989. Cholesterol and bile-acid synthesis: utilization of D2O for metabolic studies. Biomed. Environ. Mass Spectrom. 18: 624–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rittenberg D., Schoenheimer R. 1937. Deuterium as an indicator in the study of intermediary metabolism. XI. Further studies on the biological uptake of deuterium into organic substances, with special reference to fat and cholesterol formation. J. Biol. Chem. 121: 235–253. [Google Scholar]