Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is associated with a variety of lymphoid malignancies. Bortezomib activates EBV lytic gene expression. Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, leads to increased levels of CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteinβ (C/EBPβ) in a variety of tumor cell lines. C/EBPβ activates the promoter of the EBV lytic switch gene ZTA. Bortezomib treatment leads to increased binding of C/EBP to previously recognized binding sites in the ZTA promoter. Knockdown of C/EBPβ inhibits bortezomib activation of EBV lytic gene expression. Bortezomib also induces the unfolded protein response (UPR), as evidenced by increases in ATF4, CHOP10, and XBP1s and cleavage of ATF6. Thapsigargin, an inducer of the UPR that does not interfere with proteasome function, also induces EBV lytic gene expression. The effects of thapsigargin on EBV lytic gene expression are also inhibited by C/EBPβ knock-down. Therefore, C/EBPβ mediates the activation of EBV lytic gene expression associated with bortezomib and another UPR inducer.

Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–associated lymphoid malignancies include a subset of Burkitt lymphoma, AIDS lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, posttransplant lymphoma, age-associated B-cell lymphoma, and peripheral T- and NK–cell lymphoma.1–3 The EBV life cycle includes distinct lytic and latent genetic programs.4–6 In the lytic program, linear, double-stranded genomes are produced and packaged as virions that spread infection from cell to cell. In the latent program, only a few viral genes are transcribed, no viral progeny are produced, and infected cells are protected from apoptotic stimuli and in some circumstances driven to proliferate. The latent program predominates in tumors. There is increasing interest in pharmacologic activation of lytic viral gene expression in tumors.7,8 Several therapeutic strategies requiring activation of EBV lytic genes for tumor cell killing have been described,9,10 but concerns have been raised about the possible adverse effects of viral gene activation in patients treated with pharmacologic activators.11,12

To better understand the drugs that induce EBV lytic gene expression, we screened a library of drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration for human use and identified bortezomib as among the most potent.10,13 Bortezomib is a proteasome inhibitor approved for use in the treatment of myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma. The cellular pathways that mediate the apoptotic effects of bortezomib in malignancy remain the focus of active investigation, but activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) may play a critical role.14–16 In the investigations described herein, we sought to better understand the pathways by which bortezomib may activate EBV lytic program gene expression. The screening assay that identified bortezomib as a lytic inducer focused on transcriptional activation of the promoter of the EBV ZTA gene (also referred to as BZLF1, ZEBRA, Z, or EB1).17–21 ZTA is an immediate early transcriptional transactivator that induces other lytic genes and transcriptional trans-activators, resulting in virion production in permissive cell types. We were particularly interested in the possibility that CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) family members might be important in ZTA promoter activation, because there is evidence that some C/EBP family members are polyubiquitinylated and degraded by the proteasome,22,23 and also that C/EBPα and C/EBPβ bind the ZTA promoter and activate EBV lytic program gene expression.24–27

C/EBP family members share highly conserved C-terminal basic DNA-binding domains and basic leucine zipper domains (bZIPs).26,27 As homo- or heterodimers, they modulate various cellular processes, including differentiation, metabolism, inflammation, proliferation, and malignancy. C/EBPα and C/EBPβ each give rise to several different isoforms. The full-length isoforms of each protein include trans-activating and regulatory domains that can induce differentiation and inhibit proliferation. Truncated isoforms of these proteins lacking the trans-activating domains but retaining the DNA-binding and dimerization domains function as trans-dominant repressors. C/EBPβ has been identified as a critical transcription factor in multiple myeloma, regulating growth, proliferation, and antiapoptotic responses by regulating the expression of other key transcription factors.28 In addition, a role for C/EBPβ in regulating the transition from the protective to the death-promoting phase of the UPR has been proposed.29 We present evidence that bortezomib activation of the ZTA promoter is mediated by increased C/EBPβ in the context of the UPR.

Methods

Cell lines

Akata and Rael are EBV-associated Burkitt lymphoma cell lines. A subclone of the Akata cell line that lacks EBV was a gift from L. Hutt-Fletcher (Louisiana State University, Shreveport, LA).30 SNU-719 is an EBV-associated gastric carcinoma cell line (a gift from J. M. Lee, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea).31 These cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 100mM l-glutamine. AGS, a gastric carcinoma cell line lacking EBV, was maintained in Ham F12 medium containing 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 100mM l-glutamine. Each of these cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma.

Lytic induction

Cells were treated for 24-48 hours with 20nM bortezomib (Millennium Pharmaceuticals), 1μM thapsigargin (Enzo Life Sciences), or 2 μg/mL tunicamycin (Enzo Life Sciences).

Plasmids

Zp-CAT wt (pHC41) is a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter driven by the ZTA promoter (position −221 to +39).26 Zp-CAT 2M, Zp-CAT 3M, and Zp-CAT 2/3M are derivatives with mutations of the C/EBP–binding sites. Zp-Luc (pHC133) is a luciferase reporter containing the ZTA promoter from position −221 to +39.27

CAT assay

SNU-719 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. One day before transfection, 1 × 106 cells were added to each well in a 6-well plate. All cells were transfected with 4 μg of DNA. The medium was changed and cells were treated with 20nM bortezomib 24 hours after transfection. Cells were harvested at 48 hours after transfection. The CAT assay was performed using the CAT ELISA system (Roche Applied Science).

Preparation of nuclear protein extracts and immunoblotting

To prepare nuclear protein extracts, 2 × 107 cells were pelleted by centrifugation and washed in PBS. The pellet was resuspended in a low-salt buffer (10mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10mM KCl, 100μM EDTA, 1mM DTT, 0.5mM PMSF, 10 μg/mL pepstatin A, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, and 10 μg/mL aprotinin) and incubated on ice for 15 minutes. NP-40 was added to a final concentration of 0.6%, and the cells were lysed by brief vortexing. The nuclear pellet was isolated by centrifugation at 9000g for 30 seconds at 4°C, followed by resuspension in a high-salt buffer (20mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 400mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1mM DTT, 0.5mM PMSF, 10 μg/mL pepstatin A, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, and 10 μg/mL aprotinin), and rotation for 15 minutes. Nuclear debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 15 000g for 5 minutes at 4°C and the nuclear extract (supernatant) was stored at −80°C. The nuclear extract was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Proteins were detected with ECL detection reagents (GE Healthcare) and exposed to film. Primary antibodies used included anti–C/EBPα (14AA; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–C/EBPβ (H-7; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-EBV Zebra (Argene), anti–XBP-1s (BioLegend), anti-ATF6 (Abcam), anti-ATF4 (C-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-CHOP10 (B-3; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti–β-actin (Sigma-Alrich).

ChIP assay

A total of 4 × 107 EBV+ Akata cells were treated with 20nM bortezomib for 24 hours. ChIP was performed using the SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cell Signaling Technology) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For immunoprecipitation, 2 μL of anti–C/EBPβ (C-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used. To detect the immunoprecipitated EBV ZTA promoter region, 2 primers, CMO-005 (5′ GAGGAGGAGGCAGTTTTCAG 3′) and CMO-006 (5′ CTGACCCCCGAACTTAATGA 3′), were used. DNA was analyzed using both standard PCR and real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR). For standard PCR, each 50-μL reaction contained 1× Platinum PCR SuperMix (Invitrogen), 200nM primers, and 2 μL of DNA. Thermocycling conditions were 95°C for 5 minutes for 1 cycle; 95°C for 30 seconds, 54°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds for 34 cycles; and 72°C for 5 minutes for 1 cycle. The PCR products were then analyzed on a 2% agarose gel. For real-time qPCR, each 20-μL reaction contained 1× SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad), primer concentrations of 500nM, and 2 μL of DNA. Thermocycling conditions were 95°C for 30 seconds for 1 cycle and 95°C for 5 seconds and 60°C for 10 seconds for 40 cycles.

DNA transfection and luciferase assay

SNU-719 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. One day before transfection, 5 × 105 cells were added to each well in a 6-well plate. All cells were transfected with 2 μg of DNA and harvested at 48 hours after transfection. The luciferase assay was performed using a luciferase assay system kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Light intensity was measured after a 2-second delay for 10 seconds.

C/EBPβ knock-down

C/EBPβ knock-down was performed using Expression Arrest TRIPZ lentiviral shRNAmir constructs (Open Biosystems). The TRIPZ lentiviral vector is an inducible vector in which the shRNAmir is only expressed in the presence of doxycycline. In addition, miRNA is a polycistronic RNA with red fluorescent protein, making it easy to visualize shRNAmir expression. First, the shRNAmir was packaged using lentivirus. Then, 21 μg of gag/pol, 7 μg of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein, and 7 μg of shRNAmir were transfected into HEK293T cells using calcium/phosphate. Packaged lentivirus was concentrated 48 hours after transfection. Briefly, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μm syringe-driven filter unit into a filtering conical tube, then the supernatant was centrifuged at 1750g for 30 minutes at 4°C, 2 mL of cold 1× PBS was added, and the centrifugation step was repeated. The concentrated virus was stored at −80°C. Next, lentiviral particles containing shRNAmir were transduced into EBV+ Akata cells. 2 × 106 cells were added to each well in a 6-well plate. A final concentration of 8 μg/mL Polybrene and 100 μL of concentrated packaged lentivirus were added to the cells, allowed to incubate for 8 hours, and then the medium was changed. After 48 hours, 2 μg/mL puromycin was added to select for stably transduced cells (Akata C/EBPβsi). To induce shRNAmir expression, 1 μg/mL doxycycline was added to the cells for 72 hours. Because the half-life of doxycycline is 24 hours in culture, it was refreshed every 48 hours during the duration of the experiment.

Extraction of RNA, cDNA synthesis, and real-time qPCR

RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The synthesized cDNA was used as a template for C/EBPβ PCRs with primers CMO-021 (5′ TTTCGAAGTTGATGCAATCG 3′) and CMO-022 (5′ CAACAAGCCCGTAGGAACAT 3′), and ZTA PCRs with primers CMO-013 (5′ ACATCTGCTTCAACAGGAGG 3′) and CMO-014 (5′ AGCAGACATTGGTGTTCCAC 3′). Each PCR reaction contained 1× SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad), 500nM primer concentrations, cDNA corresponding to 25 ng of total RNA, and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 μL. Themocycler conditions were 95°C for 30 seconds for 1 cycle and 95°C for 5 seconds and 60°C for 10 seconds for 40 cycles. β-Actin was used as an internal control with primers CMO-023 (5′ ACAGAGCCTCGCCTTTGCCG 3′) and CMO-024 (5′ ACATGCCGGAGCCGTTGTCG 3′).

Quantification of EBV viral load by real-time qPCR

Akata C/EBPβsi cells were treated with 20nM bortezomib for 48 hours. Genomic DNA was isolated used the QIAamp DNA mini kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. To detect the EBV, 2 primers, BamH-W 5′ (5′ CCCAACACTCCACCACACC 3′) and BamH-W 3′ (5′ TCTTAGGAGCTGTCCGAGGG 3′), and the BamH-W fluorescent probe (5′ (FAM) CACACACTACACACACCCACCCGTCTC (BH1) 3′) were used. Each 50 μL of real-time qPCR reaction contained 1× IQ SuperMix (Bio-Rad), a 100nM concentration of each primer, a 100nM concentration of the probe, and 20 μL of DNA. Thermocycling conditions were 95°C for 10 minutes for 1 cycle and 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute for 40 cycles. β-actin was used as an internal control (TaqMan β-actin detection reagents; Applied Biosystems).

Results

Bortezomib leads to accumulation of C/EBPβ and increased association with Zp

C/EBPα and C/EBPβ activate ZTA promoter reporter plasmids in transient transfection experiments.24,26,27 Evidence to support a role for the ubiquitin-proteasome system in the degradation of some C/EBP family members has been reported previously.22,23 Therefore, we investigated the impact of bortezomib on C/EBPα and C/EBPβ by immunoblot analysis. In a variety of cancer cell lines, we found that bortezomib had no apparent effect on C/EBPα, but did lead to increased C/EBPβ (Figure 1A). C/EBP–binding sites had previously been identified in the ZTA promoter. Using promoter reporter plasmids with 2 binding sites, we found that mutation of either binding site diminished reporter activation, whereas mutation of both binding sites nearly abolished activation (Figure 1B). The ChIP assay showed that after bortezomib treatment there was a 3-fold increase in the binding of the endogenous C/EBPβ to ZTA promoter sites of viral genomes naturally present in an EBV-associated lymphoma cell line (Figure 1C). C/EBPβ is expressed as 3 isoforms generated by alternative translation initiation of the same mRNA transcript: LAP1, LAP2, and LIP.32 The antibody used binds to the C terminus of C/EBPβ and thus detects all 3 isoforms; it does not cross react with C/EBPα.

Figure 1.

Bortezomib modulates C/EBPβ but not C/EBPα. (A) Western blot showing C/EBPα and C/EBPβ protein levels after treatment with bortezomib in the EBV(−) gastric carcinoma cell line AGS, the EBV+ gastric carcinoma cell line SNU-719, and the Burkitt lymphoma cell lines Akata and Rael. Western blots were also probed for β-actin as a loading control. All cells were treated with 20nM bortezomib. After 24 hours of bortezomib treatment, cells were harvested and nuclear protein extracts were prepared. (B) CAT assay performed in EBV+ gastric carcinoma SNU-719 cells to assess effects of C/EBP–binding sites on activation of Zp by bortezomib. Cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing Zp-CAT with wild-type C/EBP–binding sites, one C/EBP–binding site mutated, or both sites mutated. Cells were treated with 20nM bortezomib (BZ) or DMSO for 24 hours. Assays were repeated 3 times. Error bars indicate SEM. (C) ChIP assay performed in Akata cells after treatment with 20nM bortezomib for 24 hours to show ZTA promoter (Zp) DNA bound to C/EBPβ. Immunoprecipitated Zp DNA was measured by standard PCR (top panel) and analyzed on a 2% agarose gel and by real-time qPCR (bottom panel). (D) Luciferase assay performed in SNU-719 cells to assess the effects of C/EBPβ isoforms on the Zp-Luc reporter. Cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing all 3 C/EBPβ isoforms (C/EBPβ) or the indicated C/EBPβ isoforms (LAP and LIP). Transfection with an empty parent vector (vector) was used as an internal control. Assays were repeated 3 times. Error bars indicate SEM.

Suppression of C/EBPβ expression diminishes EBV lytic induction by bortezomib

We studied individual C/EBPβ isoforms in short-term transfection experiments. A plasmid expressing only the LAP2 isoform led to Zp-luciferase activation, whereas a plasmid expressing only the LIP isoform led to Zp-luciferase inhibition, which is consistent with the presence of the N-terminal transcriptional activating domain in the LAP2 but not the LIP isoform (Figure 1D). A wild-type expression vector expressing all 3 isoforms was also associated with Zp-luciferase activation. To eliminate any effects of endogenous C/EBPβ isoforms, we also evaluated the effects of mouse C/EBPβ isoforms in a mouse C/EBPβ–knockout cell line, and again found that LAP2 was associated with activation of the ZTA promoter whereas LIP was associated with its inhibition (data not shown).

These observations are consistent with the possibility that C/EBPβ mediates the effects of bortezomib on the ZTA promoter. To determine whether suppression of C/EBPβ would interfere with bortezomib-induced lytic activation, we created a stable regulated C/EBPβ knockdown in an EBV-associated Burkitt lymphoma cell line (Akata). The cell line was engineered to express C/EBPβ shRNA from a doxycycline-activated promoter so that doxycycline treatment would reduce C/EBPβ expression. As seen in Figure 2, the addition of doxycycline was associated with a reduction in C/EBPβ RNA, and the effects of bortezomib on ZTA RNA were diminished by C/EBPβ knockdown. Immunoblot analysis showed that C/EBPβ protein expression was also inhibited by doxycycline and that bortezomib failed to increase ZTA protein in doxycycline-treated cells. In this EBV-associated Burkitt cell line, bortezomib led to the induction of lytic cycle gene expression and replication of viral DNA, but, as with ZTA RNA and ZTA protein expression, replication of viral DNA in response to bortezomib was diminished (Figure 2D). This indicates that C/EBPβ mediates EBV lytic induction by bortezomib.

Figure 2.

Effects of C/EBPβ knock-down on EBV lytic gene expression and replication by bortezomib. C/EBPβ knock-down was performed in EBV+ Akata cells using an inducible vector in which the shRNAmir is only expressed in the presence of doxycycline (DOX). To induce shRNAmir expression, 1 μg/mL doxycycline was added to cells for 72 hours. Cells were treated with 20nM bortezomib (BZ) and harvested after 24 hours. RNA was isolated and subjected to real-time qPCR with primers for C/EBPβ (A) and ZTA (B). Primers to β-actin were used as an internal control. (C) Nuclear protein extracts were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis. Blots were probed for C/EBPβ and ZTA. Blots were also probed for β-actin as a loading control. (D) Viral DNA was isolated and EBV viral load was measured using real-time PCR. Primers to the EBV BamW region were used to quantify EBV copy number. Primers to β-actin were used as an internal control. Error bars indicate SEM.

Bortezomib alters C/EBPβ transcription

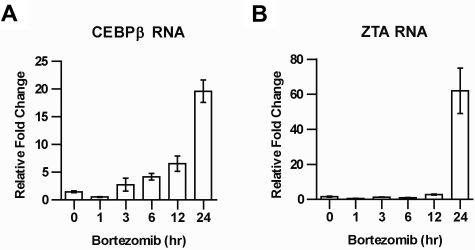

The increase in C/EBPβ protein after bortezomib treatment might be explained as a direct consequence of bortezomib-induced inhibition of the proteasomal degradation of C/EBPβ, or as an indirect consequence perhaps involving increased C/EBPβ transcription.22,23 To distinguish between these possibilities, we investigated the effect of bortezomib on C/EBPβ RNA, and found that treatment with bortezomib led to an increase in C/EBPβ RNA, followed by an increase in ZTA RNA (Figure 3A-B).

Figure 3.

Time course of C/EBPβ and ZTA RNA induction by bortezomib. EBV+ Akata cells were treated with 20nM bortezomib (BZ) and harvested at the indicated time points. RNA was isolated and subjected to real-time qPCR using primer for C/EBPβ (A) and ZTA (B). Primers for β-actin were used as an internal control. Error bars indicate SEM.

C/EBPβ and ER stress

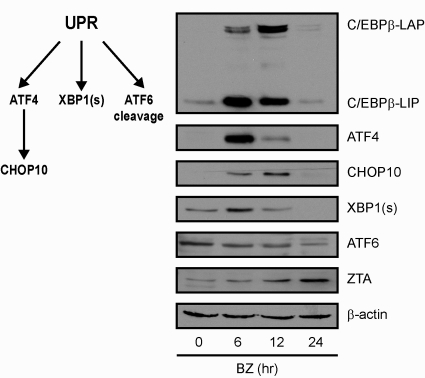

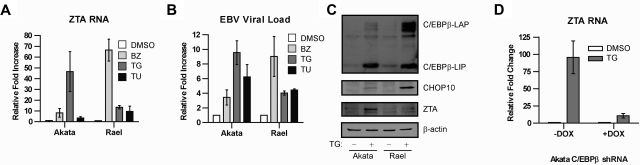

Increased transcription of C/EBPβ in the setting of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress has been described previously,33 and bor-tezomib has been shown to induce ER stress.14,34,35 ER stress activates a homeostatic response called the UPR. To better understand the context of changes in C/EBPβ and ZTA expression with regard to the UPR, we analyzed the impact of bortezomib on C/EBPβ isoforms, key UPR response indicator proteins, and ZTA by immunoblot analysis. Three ER sensors led to activation of different branches of the UPR: (1) PERK activation led to attenuation of global translation initiation but to increased translation of ATF4, a transcription factor that leads to transcription of stress response genes including CHOP10; (2) IRE1 activation led to splicing of XBP1 mRNA; and (3) ATF6 activation led to translocation from the ER to the Golgi, where it was cleaved to produce an active transcription factor. As shown in Figure 4, bortezomib led to a transient increase in ATF4, followed by a transient increase in CHOP10, a transient increase in the spliced form of XBP1 (XBP1s), and cleavage of ATF6. C/EBPβ isoforms increased in parallel with ATF4 and XBP1s and before ZTA. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the effects of bortezomib on ZTA transcription reflect activation of the UPR. If this is the case, then ZTA transcription might also be induced by very different ER stressors. We investigated thapsigargin, which disrupts the Ca2+ gradient in the ER, and tunicamycin, which inhibits the N-linked glycosylation required for proper protein folding. Both agents led to ZTA RNA expression and EBV DNA replication (Figure 5A-B). Thapsigargin elevated C/EBPβ (Figure 5C) and doxycycline-regulated knockdown of C/EBPβ expression inhibited EBV lytic induction by thapsigargin (Figure 5D).

Figure 4.

Bortezomib induces the UPR. EBV+ Akata cells were treated with 20nM bortezomib (BZ) and harvested at the indicated time points. Nuclear protein extracts were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis. Blots were probed for C/EBPβ, ATF4, CHOP10, XBP1(s), ATF6, and ZTA, and for β-actin as a loading control.

Figure 5.

C/EBPβ modulates EBV lytic gene expression and replication by ER stressors. EBV+ Akata cells and Rael were treated with 20nM bortezomib (BZ), 1μM thapsigargin (TG), or 2 μg/mL tunicamycin (TU) for 24 hours. (A) RNA was isolated and subjected to real-time qPCR using primers for ZTA. Primers for β-actin were used as an internal control. (B) Viral DNA was isolated and EBV viral load was measured using real-time PCR. Primers to the EBV BamW region were used to quantify EBV copy number. Primers to β-actin were used as an internal control. (C) EBV+ Akata and Rael cells were treated with 1μM thapsigargin (TG) and harvested after 24 hours. Western blots were probed for C/EBPβ, CHOP10, and ZTA. (D) C/EBPβ knock-down was performed in EBV+ Akata cells using an inducible vector in which the shRNAmir is only expressed in the presence of doxycycline (DOX). To induce shRNAmir expression, 1 μg/mL doxycycline was added to the cells for 72 hours. Cells were treated with 1μM thapsigargin (TG), and RNA was isolated after 24 hours and subjected to real-time qPCR with primers for ZTA. Primers to β-actin were used as an internal control. Error bars indicate SEM.

Discussion

We have presented evidence that a proteasome inhibitor activates EBV lytic gene expression in the context of ER stress, and that C/EBPβ plays a role in mediating EBV lytic gene expression in these circumstances. Proteasome inhibitors alter transcription directly by inhibiting the degradation of transcription factors, but also indirectly by activating the UPR. The observation that C/EBPβ isoforms increased after bortezomib treatment (Figure 1A) in tumor cell lines that do not harbor EBV (AGS) and in those that do harbor EBV (SNU-719, Akata, and Rael), together with previous reports that C/EBPβ activates the ZTA promoter, suggested that C/EBPβ might mediate ZTA activation.26,27 The observation that bortezomib increased C/EBPβ RNA suggested that the increase in protein detected on immunoblot analysis did not merely reflect inhibition of degradation of the protein, but also transcriptional activation of C/EBPβ.

We found that other activators of the UPR also activated the ZTA promoter and were also associated with increased expression of C/EBPβ isoforms, and that inhibition of C/EBPβ expression attenuated activation of ZTA in response to these agents. Markers of the UPR—ATF4, CHOP10, and XBP1(s)—appeared 6 hours after bortezomib treatment and had returned to baseline or near baseline by 24 hours after treatment, which may reflect cell recovery, cell death, or a combination of both.

We have provided evidence here and in previous reports that bortezomib leads to increased Zta RNA expression, ZTA protein expression, and viral DNA replication.10,13 However, not all investigators have reported EBV lytic activation with bortezomib treatment. Zou et al studied cell lines in vivo and in vitro and saw no induction of ZTA.36 However, our previous studies with tumor xenografts in mice10,13 and those presented here involved assay at 24 hours or fewer, whereas in the report by Zou et al, mice bearing xenografts were treated with bortezomib for 6 weeks and then observed off-treatment for 5 weeks before tumor tissues were assayed.36 We suspect that the long time interval between bortezomib treatment and assays explains why these investigators did not observe lytic activation. Zou et al also reported no evidence of lytic activation in vitro in EBV-immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines.36 We suspect that the different observations reflect the fact that lymphoblastoid cell lines express EBNA-3C, which modulates the UPR by inhibiting splicing of XBP-1 and activation cleavage of ATF6.37 The cell lines studied in the present study and in our previous studies do not express EBNA-3C.

Viruses have long been recognized as important inducers of the UPR. From the perspective of the virus, the UPR presents formidable obstacles to be overcome. To assemble virions, viral proteins must be synthesized. Investigations have identified several different strategies for overcoming translational inhibition among the human herpesviruses.37–39 Several previous investigators have reported that UPR-associated pathways affect EBV gene expression. The latency membrane protein 1 (LMP1) promoter is activated by ATF4 and by XBP1(s).40,41 The ZTA promoter is activated by XBP1(s), which functions both as an effector of the UPR and as a plasma cell differentiation factor.42–44 The role of C/EBPβ in the UPR has only recently been recognized. Early in the UPR, cells are protected from further accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins by inhibition of global translation, synthesis of chaperone and other proteins important for protein folding, and by activation of ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD). If homeostasis is not restored, then apoptotic pathways are later activated. C/EBPβ isoforms play a critical role in triggering the transition from the early protective phase to the late apoptotic phase.33 C/EBPβ is a member of the bZIP family of transcription factors and may homo- or heterodimerize with other bZIP proteins. LAP and LIP isoforms may dimerize with each other, but C/EBPβ isoforms may also dimerize with other partners, such as CHOP10. Recently, evidence for direct interactions between ZTA and C/EBPβ has been reported.45 The dimerization partner and the promoter-binding site are both important determinants of transcriptional activity.

In closing, this study puts bortezomib activation of the EBV lytic cycle into a broader context. C/EBPβ induction by bortezomib mediates ZTA induction. Similarly, C/EBPβ induction by thapsigargin mediates ZTA induction. Both agents lead to ER stress and activation of the UPR. A better understanding of the interplay between viral gene regulation and cellular stress responses, including the UPR, promise to facilitate the development of new therapeutic approaches to EBV-associated tumors, perhaps preventing the potential adverse effects of viral reactivation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P50 CA96888 and P01CA1539627 (to R.F.A.)

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: C.M.S. and J.C. carried out the experiments; C.M.S., M.S., and R.A. designed the experiments; H.L., C.A.Z., and S.D.H. contributed plasmids and cell lines and critiqued the experimental design; and C.M.S. and R.F.A. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Richard F. Ambinder, Department of Oncology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 389 CRB1, 1650 Orleans, Baltimore, MD 21287; e-mail: rambind1@jhmi.edu.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(12):3030–3044. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen JI, Kimura H, Nakamura S, Ko YH, Jaffe ES. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease in non-immunocompromised hosts: a status report and summary of an international meeting, 8-9 September 2008. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(9):1472–1482. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thorley-Lawson DA, Gross A. Persistence of the Epstein-Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(13):1328–1337. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorley-Lawson DA, Allday MJ. The curious case of the tumour virus: 50 years of Burkitt's lymphoma. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6(12):913–924. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen JI, Bollard CM, Khanna R, Pittaluga S. Current understanding of the role of Epstein-Barr virus in lymphomagenesis and therapeutic approaches to EBV-associated lymphomas. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(suppl 1):27–34. doi: 10.1080/10428190802311417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrell PJ. Tumour viruses–could they be an Achilles' heel of cancer? Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(14):1815–1816. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng WH, Hong G, Delecluse HJ, Kenney SC. Lytic induction therapy for Epstein-Barr virus-positive B-cell lymphomas. J Virol. 2004;78(4):1893–1902. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1893-1902.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perrine SP, Hermine O, Small T, et al. A phase 1/2 trial of arginine butyrate and ganciclovir in patients with Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoid malignancies. Blood. 2007;109(6):2571–2578. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-024703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu DX, Tanhehco Y, Chen J, et al. Bortezomib-induced enzyme-targeted radiation therapy in herpesvirus-associated tumors. Nat Med. 2008;14(10):1118–1122. doi: 10.1038/nm.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klass CM, Krug LT, Pozharskaya VP, Offermann MK. The targeting of primary effusion lymphoma cells for apoptosis by inducing lytic replication of human herpesvirus 8 while blocking virus production. Blood. 2005;105(10):4028–4034. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng WH, Cohen JI, Fischer S, et al. Reactivation of latent Epstein-Barr virus by methotrexate: a potential contributor to methotrexate-associated lymphomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(22):1691–1702. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu DX, Tanhehco YC, Chen J, et al. Virus-associated tumor imaging by induction of viral gene expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(5):1453–1458. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obeng EA, Carlson LM, Gutman DM, Harrington WJ, Jr, Lee KP, Boise LH. Proteasome inhibitors induce a terminal unfolded protein response in multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2006;107(12):4907–4916. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strasser A, Puthalakath H. Fold up or perish: unfolded protein response and chemotherapy. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(2):223–225. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong H, Chen L, Chen X, et al. Dysregulation of unfolded protein response partially underlies proapoptotic activity of bortezomib in multiple myeloma cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50(6):974–984. doi: 10.1080/10428190902895780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Countryman J, Jenson H, Seibl R, Wolf H, Miller G. Polymorphic proteins encoded within BZLF1 of defective and standard Epstein-Barr viruses disrupt latency. J Virol. 1987;61(12):3672–3679. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3672-3679.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lieberman PM, Hardwick JM, Sample J, Hayward GS, Hayward SD. The zta transactivator involved in induction of lytic cycle gene expression in Epstein-Barr virus-infected lymphocytes binds to both AP-1 and ZRE sites in target promoter and enhancer regions. J Virol. 1990;64(3):1143–1155. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1143-1155.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin Z, Yin Q, Flemington E. Identification of a negative regulatory element in the Epstein-Barr virus Zta transactivation domain that is regulated by the cell cycle control factors c-Myc and E2F1. J Virol. 2004;78(21):11962–11971. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11962-11971.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller G, El-Guindy A, Countryman J, Ye J, Gradoville L. Lytic cycle switches of oncogenic human gammaherpesviruses. Adv Cancer Res. 2007;97:81–109. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)97004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rennekamp AJ, Wang P, Lieberman PM. Evidence for DNA hairpin recognition by Zta at the Epstein-Barr virus origin of lytic replication. J Virol. 2010;84(14):7073–7082. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02666-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hattori T, Ohoka N, Inoue Y, Hayashi H, Onozaki K. C/EBP family transcription factors are degraded by the proteasome but stabilized by forming dimer. Oncogene. 2003;22(9):1273–1280. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei W, Yang H, Menconi M, Cao P, Chamberlain CE, Hasselgren PO. Treatment of cultured myotubes with the proteasome inhibitor beta-lactone increases the expression of the transcription factor C/EBPbeta. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292(1):C216–226. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00282.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu FY, Chen H, Wang SE, et al. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha interacts with ZTA and mediates ZTA-induced p21(CIP-1) accumulation and G(1) cell cycle arrest during the Epstein-Barr virus lytic cycle. J Virol. 2003;77(2):1481–1500. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1481-1500.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang J, Chen H, Hutt-Fletcher L, Ambinder RF, Hayward SD. Lytic viral replication as a contributor to the detection of Epstein-Barr virus in breast cancer. J Virol. 2003;77(24):13267–13274. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.13267-13274.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu FY, Wang SE, Chen H, Wang L, Hayward SD, Hayward GS. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha binds to the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) ZTA protein through oligomeric interactions and contributes to cooperative transcriptional activation of the ZTA promoter through direct binding to the ZII and ZIIIB motifs during induction of the EBV lytic cycle. J Virol. 2004;78(9):4847–4865. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4847-4865.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang J, Liao G, Chen H, et al. Contribution of C/EBP proteins to Epstein-Barr virus lytic gene expression and replication in epithelial cells. J Virol. 2006;80(3):1098–1109. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1098-1109.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pal R, Janz M, Galson DL, et al. C/EBPbeta regulates transcription factors critical for proliferation and survival of multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2009;114(18):3890–3898. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-201111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meir O, Dvash E, Werman A, Rubinstein M. C/EBP-beta regulates endoplasmic reticulum stress-triggered cell death in mouse and human models. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(3):e9516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takada K. Role of Epstein-Barr virus in Burkitt's lymphoma. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001;258:141–151. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56515-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ji Jung E, Mie Lee Y, Lan Lee B, Soo Chang M, Ho Kim W. Ganciclovir augments the lytic induction and apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents in an Epstein-Barr virus-infected gastric carcinoma cell line. Anticancer Drugs. 2007;18(1):79–85. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3280101006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Descombes P, Schibler U. A liver-enriched transcriptional activator protein, LAP, and a transcriptional inhibitory protein, LIP, are translated from the same mRNA. Cell. 1991;67(3):569–579. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Bevilacqua E, Chiribau CB, et al. Differential control of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPbeta) products liver-enriched transcriptional activating protein (LAP) and liver-enriched transcriptional inhibitory protein (LIP) and the regulation of gene expression during the response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(33):22443–22456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801046200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nawrocki ST, Carew JS, Dunner K, Jr, et al. Bor-tezomib inhibits PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum (ER) kinase and induces apoptosis via ER stress in human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(24):11510–11519. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armstrong JL, Flockhart R, Veal GJ, Lovat PE, Redfern CP. Regulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cell death by ATF4 in neuroectodermal tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(9):6091–6100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.014092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou P, Kawada J, Pesnicak L, Cohen JI. Bor-tezomib induces apoptosis of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-transformed B cells and prolongs survival of mice inoculated with EBV-transformed B cells. J Virol. 2007;81(18):10029–10036. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02241-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garrido JL, Maruo S, Takada K, Rosendorff A. EBNA3C interacts with Gadd34 and counteracts the unfolded protein response. Virol J. 2009;6:231. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng G, Feng Z, He B. Herpes simplex virus 1 infection activates the endoplasmic reticulum resident kinase PERK and mediates eIF-2alpha dephosphorylation by the gamma(1) 34.5 protein. J Virol. 2005;79(3):1379–1388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1379-1388.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buchkovich NJ, Yu Y, Pierciey FJ, Jr, Alwine JC. Human cytomegalovirus induces the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone BiP through increased transcription and activation of translation by using the BiP internal ribosome entry site. J Virol. 2010;84(21):11479–11486. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01330-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee DY, Sugden B. The LMP1 oncogene of EBV activates PERK and the unfolded protein response to drive its own synthesis. Blood. 2008;111(4):2280–2289. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsiao JR, Chang KC, Chen CW, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers XBP-1-mediated up-regulation of an EBV oncoprotein in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69(10):4461–4467. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun CC, Thorley-Lawson DA. Plasma cell-specific transcription factor XBP-1s binds to and transactivates the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 promoter. J Virol. 2007;81(24):13566–13577. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01055-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhende PM, Dickerson SJ, Sun X, Feng WH, Kenney SC. X-box-binding protein 1 activates lytic Epstein-Barr virus gene expression in combination with protein kinase D. J Virol. 2007;81(14):7363–7370. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00154-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDonald C, Karstegl CE, Kellam P, Farrell PJ. Regulation of the Epstein-Barr virus Zp promoter in B lymphocytes during reactivation from latency. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(pt 3):622–629. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.017277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bristol JA, Robinson AR, Barlow EA, Kenney SC. The Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 protein inhibits tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 expression through effects on cellular C/EBP proteins. J Virol. 2010;84(23):12362–12374. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00712-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]