Abstract

Homeostatic mechanisms maintaining high levels of adhesion molecules in synapses over prolonged periods of time remain incompletely understood. We used fluorescence recovery after photobleaching experiments to analyze the steady state turnover of the immobile pool of green fluorescent protein-labeled NCAM180, the largest postsynaptically accumulating isoform of the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM). We show that there is a continuous flux of NCAM180 to the postsynaptic membrane from nonsynaptic regions of dendrites by diffusion. In the postsynaptic membrane, the newly delivered NCAM180 slowly intermixes with the immobilized pool of NCAM180. Preferential immobilization and accumulation of NCAM180 in the postsynaptic membrane is reduced after disruption of the association of NCAM180 with the spectrin cytoskeleton and in the absence of the homophilic interactions of NCAM180 in synapses. Our observations indicate that the homophilic interactions and binding to the cytoskeleton promote immobilization of NCAM180 and its accumulation in the postsynaptic membrane. Flux of NCAM180 from extrasynaptic regions and its slow intermixture with the immobile pool of NCAM180 in the postsynaptic membrane may be important for the continuous homeostatic replenishment of NCAM180 protein at synaptic contacts without compromising the long term synaptic contact stability.

Keywords: Cell Adhesion, Neurobiology, Neurochemistry, Neuron, Synapses

Introduction

Neurons are assembled into circuits via specialized contacts, called synapses, that are essential for information processing, learning, and storage in the brain. Synapses are stable long lasting structures (1–3). This stability is at least partially rendered by a number of cell adhesion molecules accumulating in the pre- and postsynaptic membranes (4–9). During development, cell adhesion molecules are delivered to nascent synapses in intracellular organelles or as cell surface aggregates (10–12). A similar type of quantal delivery of adhesion molecules has been also observed during induction of long term potentiation (13). Long lasting stability of synapses (months or years), however, suggests that synaptic pools of cell adhesion molecules (protein life time hours or days) have to be also homeostatically and continuously replenished over prolonged periods of time without compromising synapse stability and composition. Mechanisms of such replenishment remain poorly understood.

Among synaptic adhesion molecules, the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM),2 a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily of adhesion molecules, was shown to be involved in mechanical stabilization of interneuronal contacts and their transformation into synapses (12, 14). In mice, deficiency in NCAM results in impaired long term potentiation, increased aggression and anxiety, deficits in spatial learning, and exploratory behavior (15–21). In humans, genetic variations in the NCAM gene have been reported to confer risk factors associated with bipolar affective disorders and schizophrenia (22–24). The largest isoform of NCAM, NCAM180, accumulates in the postsynaptic membrane and recruits the spectrin scaffold, NMDA-type glutamate receptors, and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase α (CaMKIIα) (25–27), whereas polysialic acid attached to NCAM restrains the signaling through GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors, a process that is required for synaptic plasticity and learning (28).

In the present study, we used fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) to analyze the turnover of green fluorescent protein-labeled NCAM (NCAM180GFP) in the postsynaptic membrane of cultured hippocampal neurons. Our data indicate that at the steady state there is a continuous flux of NCAM180GFP to the postsynaptic membrane from the extrasynaptic regions via diffusion and that this newly delivered NCAM180GFP slowly intermixes with the immobilized pool of postsynaptic NCAM180GFP. The postsynaptic spectrin cytoskeleton and homophilic interactions of NCAM regulate immobilization and overall levels of NCAM180GFP in the postsynaptic membrane but do not significantly affect the diffusion of NCAM180GFP to the postsynaptic site. We propose that flux of NCAM180 from the extrasynaptic membrane is required for the homeostatic refreshment of the synaptic pool of NCAM180.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cultures of Hippocampal Neurons

Cultures of hippocampal neurons were prepared from 1–3-day-old C57BL/6J or NCAM-deficient (NCAM−/−) mice from homozygous breeding pairs and maintained on glass coverslips as described (29). NCAM−/− mice were provided by Harold Cremer (30) and were inbred for at least nine generations onto the C57BL/6J background. All of the experiments were conducted in accordance with the German and European Community laws on protection of experimental animals, and all of the procedures used were approved by the responsible committee of the State of Hamburg. For time lapse video recordings, the cells were maintained in Corning dishes (35 mm in diameter) with glass bottoms (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA). Hippocampal neurons were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Synapses were labeled by incubating cultures for 90 s in modified Tyrode solution containing 47 mm KCl and 10 μm FM4-64 (Invitrogen). Latrunculin A (5 μm; Biomol, Hamburg, Germany) was applied for 2 h (31). Dishes were transferred to the CO2 incubator (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) of the confocal laser scanning microscope for recording at 35 °C and 5% CO2.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy and Photobleaching

Transfected hippocampal neurons were imaged on the LSM510 laser scanning microscope (Zeiss). A high numerical aperture oil immersion objective (×40, 1.4 NA) was used to maximize the collection of the emitted fluorescent light. During image acquisition, the power of the 15-milliwatt argon laser (with the excitation wavelength of 488 nm) was minimized to reduce photodamage to cells and photobleaching of the GFP tag. The adjustable confocal aperture was completely opened to increase the fluorescence signal and to increase the depth of field so that minor fluctuations in the focus during image acquisition would not erroneously contribute to the signal. Photobleaching and image acquisition were performed automatically using the time series program of the LSM510 software. Before photobleaching, several images of the area of interest were acquired to record base-line fluorescence intensity.

Data Analysis of FRAP Experiments

For analysis, the average pixel intensity of the photobleached region of the neurite for each time point before and after photobleaching was measured from the original stored images using LSM510 software. The background values measured near the bleached region were subtracted.

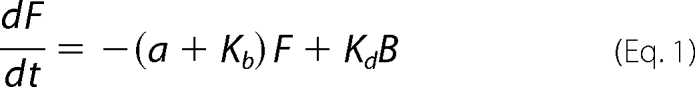

Mathematical Model of the Diffusion of NCAM180GFP and the Kinetics of Binding to Scaffold Proteins

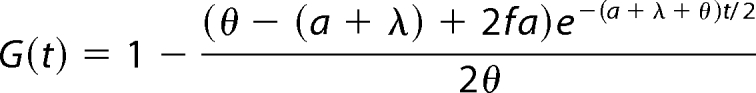

To predict the behavior of NCAM180GFP molecules in the membrane, we defined F, B, and G to be, respectively, the number of free (bleached), bound (bleached), and green fluorescent molecules normalized by the total number. The green molecules may be free or bound. If a be the rate of diffusion in the membrane, Kb is the rate of binding to the scaffold proteins, and Kd is the dissociation rate from the scaffold, then the kinetics can be described by the following system of ordinary differential equations,

|

|

|

where t is time measured in seconds. The equilibrium between free and bound molecules occurs at a fraction f = Kd/(Kb + Kd) of molecules unbound. Assuming binding is at steady state at the time of photobleaching, the initial conditions are F(0) = f, B(0) = 1 − f, G(0) = 0, and the solution of the above system of equations is

|

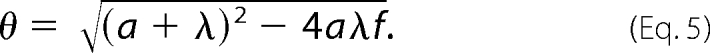

where λ = Kb + Kd and where

|

Note that the case in which only diffusion acts can be found by setting Kb = 0 and taking the limit as Kd → 0, in which case the concentration of green molecules reduces to G(t) = 1 − e−at.

For a given experiment, the solution (Equation 4) can be fitted to data to obtain estimates of a, f, and θ. The ratio Kd/Kb can then be estimated as f/(1 − f).

To test whether the inclusion of binding and dissociation improved the model fit, we used the lack-of-fit test with degrees of freedom (2, n − 3) for each data set from each individual time lapse experiment, where n is the sample size. For 26 of 27 data sets, the resulting p value was <10−6, indicating that the model with binding and diffusion was statistically superior to the model with only diffusion.

RESULTS

NCAM180GFP Diffuses to Sites of Interneuronal Contacts

To visualize the behavior of NCAM180 in live neurons, cultured hippocampal neurons were transfected with NCAM180 tagged with the GFP inserted between its transmembrane and second fibronectin type III domains to ensure that the tag does not interfere with the interactions mediated by the extracellular and intracellular domains of NCAM (12). In neurons from early postnatal mice maintained for 5 days in vitro, NCAM180GFP was broadly expressed along neurites and in somata (Fig. 1). This distribution was similar to the distribution of endogenous NCAM detected with NCAM antibodies (not shown). NCAM180GFP accumulated at sites of contacts between neurons, visualized as intersections between neurites of NCAM180GFP transfected neurons (Fig. 1), in accordance with previous reports for endogenous NCAM (12, 32).

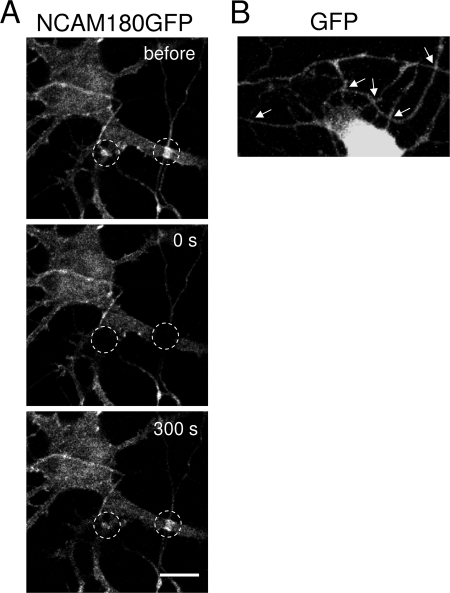

FIGURE 1.

NCAM180GFP preferentially accumulates at contact sites. A, an example of a FRAP experiment with a hippocampal neuron maintained in culture for 4 days and transfected with NCAM180GFP. Contacts (circles) were irreversibly photobleached, and recovery of NCAM180GFP fluorescence was monitored with time. Note that NCAM180GFP fluorescence is increased at contact sites before photobleaching and that NCAM180GFP fluorescence reaccumulates at the contact sites after photobleaching. B, an example of a GFP transfected neuron maintained in culture for 4 days. Note that GFP does not accumulate at contact sites. Scale bar, 10 μm for A and B.

Next, we asked whether there is an exchange in NCAM180GFP molecules between interneuronal contacts and neighboring regions of neurites. To analyze this, FRAP experiments were performed. Clusters of NCAM180GFP at intersections of transfected neurites were irreversibly photobleached with a high intensity laser beam of 488-nm wavelength. Time lapse imaging showed that NCAM180GFP fluorescence rapidly recovered at the contact sites (Fig. 1). NCAM180GFP fluorescence intensity at contact sites recovered not only to the basal levels of the fluorescence intensity at regions surrounding the contact but increased above this level so that the preferential accumulation of NCAM180GFP fluorescence at the contact site was restored (Fig. 1). One possible explanation for this observation is that the preferential increase in fluorescence levels at contacts is due to the superposition of the fluorescence signals in neurites at the point of the intersection. However, this preferential accumulation of fluorescence was only observed at contacts formed by neurons transfected with NCAM180GFP but not at contacts formed by neurons transfected with GFP, thus arguing against this possibility (Fig. 1). To exclude this possibility in a more direct manner, further analysis was performed on synaptic contacts in which contact sites in live neurons were visualized using markers of synaptic vesicles (see below).

NCAM180GFP Fluorescence Recovers Nonuniformly in the Postsynaptic but Not in the Nonsynaptic Membrane

In mature neurons, NCAM180 accumulates postsynaptically (25, 26). To identify postsynaptic regions in NCAM180GFP transfected neurons, synaptic boutons of hippocampal neurons maintained in culture for 2 weeks were loaded with the lipophilic dye FM4-64 by a brief incubation in high K+ solution (47 mm K+, 90 s) in the presence of the dye (12, 25, 33, 34). NCAM180GFP accumulations in dendrites apposed to FM4-64 clusters were then identified as postsynaptic (Fig. 2A).

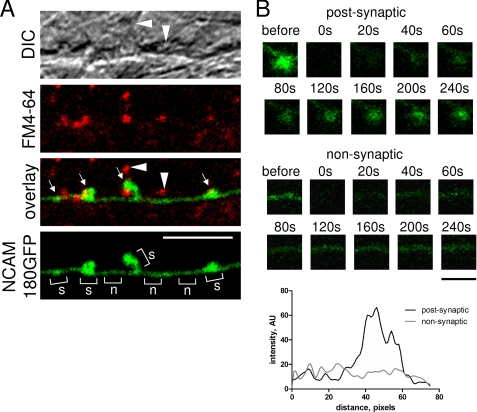

FIGURE 2.

Example of a FRAP experiment with a hippocampal neuron maintained in culture for 14 days and transfected with NCAM180GFP. A, an NCAM180GFP (green) transfected neurite is shown. Synapses were loaded with FM4-64 (red). Note NCAM180GFP accumulations apposed to FM4-64 clusters (arrows). FM4-64 clusters that are not apposed to NCAM180GFP accumulations are also seen. These FM4-64 clusters belong to synapses formed on nontransfected neurites seen by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy (arrowheads). Examples of synaptic (s) and nonsynaptic (n) regions are shown with brackets on the NCAM180GFP microscopic image. Scale bar, 5 μm. B, examples of time lapse sequences from FRAP measurements performed for postsynaptic and nonsynaptic regions. NCAM180GFP fluorescence was irreversibly photobleached, and recovery of NCAM180GFP fluorescence was monitored with time. Note that NCAM180GFP fluorescence reaccumulates preferentially in the postsynaptic region and shows uniform recovery all over the nonsynaptic region. The graph shows the respective profiles of NCAM180GFP fluorescence intensity measured along postsynaptic and nonsynaptic regions of the dendrite at 240 s after photobleaching. Scale bar, 1 μm.

Preferential accumulation of NCAM180 in the postsynaptic membrane was estimated by analyzing the ratio of NCAM180GFP fluorescence level in the postsynaptic membrane to the NCAM180GFP fluorescence levels in the neighboring nonsynaptic regions. This analysis showed that the level of NCAM180GFP was approximately two times higher in the postsynaptic membrane when compared with nonsynaptic regions (Figs. 2 and 3B; see also Fig. 7).

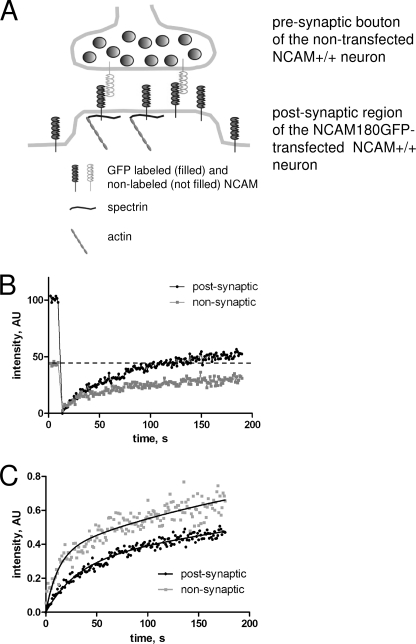

FIGURE 3.

Example of FRAP experiments with NCAM+/+ neurons. A, scheme of molecular interactions between postsynaptic NCAM180GFP and synaptic scaffold in wild-type (NCAM+/+) synapses. NCAM180GFP can either be free or in a complex with presynaptic NCAM, postsynaptic intracellular spectrin, or both (shown from the right to the left in the synapse). For simplicity, endogenous postsynaptic NCAM180 is not shown. B, example of FRAP measurements in the postsynaptic (black) and nonsynaptic (gray) regions from one experiment. Note higher prebleach levels of NCAM180GFP in the postsynaptic region. After bleaching, NCAM180GFP fluorescence in the postsynaptic region recovers to a higher level compared with the recovery of NCAM180GFP fluorescence in the nonsynaptic region. The dashed line shows prebleach levels in the nonsynaptic region. C, recovery curves from B normalized to prebleach NCAM180GFP levels. Note faster and more complete recovery in the nonsynaptic versus postsynaptic regions. Approximation curves used to calculate diffusion rates and Kd/Kb are shown as solid lines.

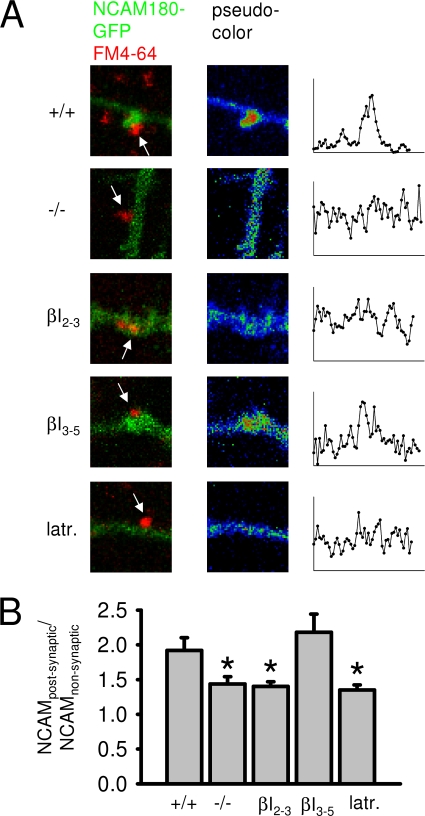

FIGURE 7.

Preferential accumulation of NCAM180GFP in the postsynaptic membrane is reduced in the absence of the homophilic interactions of NCAM180GFP or its association with the spectrin cytoskeleton. A, examples of synapses formed on dendrites of NCAM180GFP-transfected NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− neurons and NCAM+/+ neurons transfected with βI2–3 or βI3–5 spectrin fragments or treated with latrunculin (latr.). Synaptic boutons of presynaptic nontransfected neurons were loaded with FM4-64. Pseudocolor images of NCAM180GFP fluorescence intensity and profiles of NCAM180GFP distribution in the vicinity of synapses are shown on the right. B, accumulation of NCAM180GFP in the postsynaptic membrane was estimated as a ratio of NCAM180GFP fluorescence in the postsynaptic membrane to NCAM180GFP fluorescence in the adjacent nonsynaptic region (NCAMpostsynaptic/NCAMnonsynaptic). The graph presents mean values ± S.E. of NCAMpostsynaptic/NCAMnonsynaptic for NCAM180GFP transfected NCAM+/+ neurons, NCAM−/− neurons, and NCAM+/+ neurons co-transfected with βI2–3 or βI3–5 spectrin fragments or treated with latrunculin. Note that NCAM180GFP accumulates postsynaptically in NCAM+/+ neurons and NCAM+/+ neurons co-transfected with βI3–5 (NCAMpostsynaptic/NCAMnonsynaptic = ∼2). The ratio is reduced in NCAM−/− neurons and NCAM+/+ neurons co-transfected with βI2–3 or treated with latrunculin. *, p < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance (Dunnett's multiple comparison test, compared with NCAM+/+ neurons transfected with NCAM180GFP only (first bar)).

Transfection conditions were chosen to result in very low transfection efficiency so that the majority (>95%) of neurons in each culture were NCAM180GFP-negative. Under these conditions, NCAM180GFP fluorescence could be specifically attributed to the postsynaptic transfected neuron, whereas FM4-64-positive boutons belonged to NCAM180GFP negative nontransfected neurons. The exchange of NCAM180GFP molecules between the postsynaptic membrane and nonsynaptic regions of dendrites was then analyzed in FRAP experiments. In each experiment, a 3-μm-long region of a dendritic surface membrane of the NCAM180GFP transfected neuron apposed to a FM4-64 loaded synaptic bouton was irreversibly photobleached with a high intensity laser beam, and recovery of NCAM180GFP fluorescence in the photobleached area was monitored over time (Fig. 2B). Time lapse recordings showed that, similarly to contacts in immature neurons, NCAM180GFP fluorescence recovered in the photobleached area, indicating that NCAM180GFP moves into the postsynaptic membrane from nonsynaptic regions. The recovery occurred in a gradual fashion without any obvious steep quantal increases in fluorescence (Fig. 2B), which would be characteristic of vesicular delivery of NCAM180GFP. The latter suggested that NCAM180GFP entered the postsynaptic membrane by diffusion. NCAM180GFP fluorescence recovery occurred in a nonuniform manner with the strongest recovery observed in the center of the synaptic contacts when compared with the adjacent segments of the dendrite (Fig. 2B).

For comparison, in each experiment NCAM180GFP fluorescence recovery after photobleaching was also analyzed in the regions located on the same dendrite but 5–10 μm away from the postsynaptic region (Fig. 2). These dendritic regions were chosen to be not apposed to FM4-64 loaded synaptic boutons and were thus identified as nonsynaptic. Similarly to postsynaptic regions, NCAM180GFP fluorescence rapidly recovered in the photobleached nonsynaptic regions (Fig. 2B). In contrast to the postsynaptic regions, NCAM180GFP fluorescence in nonsynaptic segments recovered uniformly all over the bleached area (Fig. 2B).

Recovery of NCAM180GFP Localization in the Postsynaptic Membrane Can Be Explained by Diffusion and Replenishment of the Immobilized Pool

In FRAP experiments, the postphotobleaching recovery level is often considered as a measure of the freely diffusible pool of molecules, which can be assumed to be the same or lower in the postsynaptic membrane when compared with extrasynaptic regions. However, quantification of FRAP experiments showed that in a typical synaptic contact, postsynaptic NCAM180GFP fluorescence recovered above the levels observed in nonsynaptic regions within several minutes after photobleaching (Fig. 3B).

The initial levels of NCAM180GFP fluorescence were approximately two times higher in the postsynaptic membrane versus the nonsynaptic membrane (Fig. 3B). To take into account these differences in expression levels, NCAM180GFP levels were normalized to the prebleach levels in the region analyzed. A comparison of the normalized curves showed that NCAM180GFP fluorescence recovery was slower in postsynaptic versus nonsynaptic regions (Fig. 3C). Altogether, these differences in postphotobleaching recovery behavior suggested that the recovery of NCAM180GFP fluorescence was not determined only by the freely diffusible pool of NCAM180GFP.

A possible explanation for the reaccumulation of NCAM180GFP fluorescence in the postsynaptic membrane in FRAP experiments is that NCAM180GFP not only diffuses to the postsynaptic regions from the nonsynaptic regions but also binds to the synaptic scaffold during the time lapse recordings and substitutes immobilized NCAM180GFP, which was photobleached. To analyze this possibility, we developed a mathematical model to predict the behavior of NCAM180GFP in the membrane. NCAM180 has been shown to bind via the intracellular domain to spectrin molecules (25, 35) and is expected to interact via the extracellular domain with extracellular domains of other adhesion molecules in the synaptic cleft (Fig. 3A). Hence, a model describing the behavior of NCAM180GFP as a function of rates of diffusion and binding and dissociation from the synaptic scaffold proteins including postsynaptic spectrin and NCAM molecules on adjacent presynaptic membrane was developed. This model was then used to fit the normalized experimental data. A comparison with the model considering only the diffusion of NCAM180 showed that the model considering binding of NCAM180 to the synaptic scaffold provided a statistically significantly better fit of the experimental recovery curves. This analysis showed that the diffusion rate tended to be lower (although statistically not significantly) in the postsynaptic membrane when compared with the nonsynaptic regions (Table 1). A significant proportion of NCAM180GFP was found in the immobile pool both in synaptic and nonsynaptic regions. The immobile pool of NCAM180GFP was, however, predicted to be significantly increased up to 59 ± 2.7% of the total pool of NCAM180GFP in the postsynaptic membrane versus 48 ± 1.9% of the total pool of NCAM180GFP in the nonsynaptic membrane. To characterize the interactions of NCAM180GFP with the scaffold molecules, the ratio of the dissociation rate from the scaffold to the rate of binding to the scaffold (Kd/Kb) was analyzed using the model parameters. The predicted Kd/Kb was significantly lower in postsynaptic (0.82 ± 0.11) versus nonsynaptic (1.16 ± 0.1) regions (Table 1), suggesting enhanced binding to and lower dissociation of NCAM180 from the molecular scaffolds in synapses.

TABLE 1.

Diffusion rates and immobilization parameters for NCAM180GFP in the postsynaptic membrane

The immobile pool of NCAM180GFP is increased, and the Kd/Kb values are reduced in the postsynaptic membrane of NCAM+/+ neurons, but not in NCAM−/− neurons or NCAM+/+ neurons transfected with βI2–3 or treated with latrunculin. The mean values ± S.E. are shown for Kd/Kb values, and the size of the immobile pool of NCAM180GFP in transfected NCAM+/+ neurons, NCAM−/− neurons, and NCAM+/+ neurons co-transfected with βI2–3 or βI3–5 spectrin fragments or treated with latrunculin. Pairs of values for postsynaptic and nonsynaptic regions that are statistically significantly different are shown in bold.

| Treatment | Diffusion rate, 10−2 |

Kd/Kb |

Immobile pool |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postsynaptic | Nonsynaptic | Postsynaptic | Nonsynaptic | Postsynaptic | Nonsynaptic | |

| None | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 0.82 ± 0.11a | 1.16 ± 0.10 | 59 ± 2.7%a | 48 ± 1.9% |

| NCAM−/− | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 0.99 ± 0.07 | 1.02 ± 0.10 | 48 ± 4.0% | 52 ± 2.3% |

| βI2–3 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 1.16 ± 0.10 | 1.17 ± 0.22 | 48 ± 1.7% | 52 ± 3.5% |

| βI3–5 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 0.43 ± 0.06a | 0.82 ± 0.13 | 71 ± 3.0%a | 58 ± 3.7% |

| Latrunculin | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 1.084 ± 0.11 | 1.34 ± 0.17 | 50 ± 2.4% | 45 ± 3.2% |

a p < 0.05, t test.

Homophilic Interactions of NCAM180GFP Increase Its Immobilization in the Postsynaptic Membrane

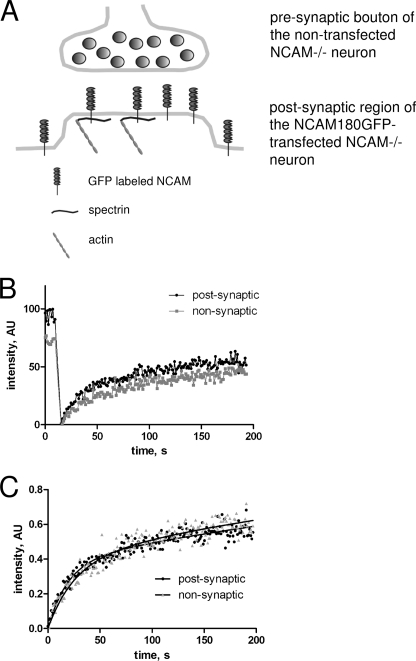

Next, we analyzed the role of the homophilic interactions of NCAM180 for its immobilization in the postsynaptic membrane by analyzing the postphotobleaching recovery of NCAM180GFP fluorescence in the postsynaptic membrane in the absence of interactions of the postsynaptic NCAM180GFP with NCAM molecules in the presynaptic membrane (Fig. 4A). In these experiments, neurons from NCAM-deficient (NCAM−/−) mice (30) were maintained in culture and transfected with NCAM180GFP. Transfection conditions were chosen to obtain very low transfection efficiency, so that only 1% or less of neurons in culture expressed NCAM180GFP. Most of the synaptic contacts received by NCAM180GFP transfected neurons were formed by axons from nontransfected NCAM negative neurons, implying that postsynaptic NCAM180GFP was not engaged in the homophilic interactions with presynaptic NCAM (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Example of FRAP experiments with NCAM−/− neurons transfected with NCAM180GFP. A, scheme of molecular interactions between postsynaptic NCAM180GFP and synaptic scaffold in NCAM−/− neurons transfected with NCAM180GFP. Note that the presynaptic membrane is NCAM negative because it belongs to a nontransfected and thus NCAM-negative neuron. In the postsynaptic membrane, NCAM180GFP can either be free or in a complex with postsynaptic intracellular spectrin, but not in a complex with presynaptic NCAM. B, example of FRAP measurements in the postsynaptic (black) and nonsynaptic (gray) regions from one experiment. C, recovery curves from B normalized to prebleach NCAM180GFP levels. Approximation curves used to calculate diffusion rates and Kd/Kb are shown as solid lines. Note that NCAM180GFP fluorescence recovers to similar levels in the nonsynaptic and postsynaptic regions.

Analysis of such synapses showed that preferential accumulation of NCAM180GFP in the postsynaptic membrane was reduced by ∼50% in the absence of the homophilic interactions of NCAM180GFP (compare prebleach levels in Fig. 4; see also Fig. 7). Analysis of the FRAP curves with the model equations showed that Kd/Kb in postsynaptic regions was increased, and the immobile pool of NCAM180GFP was reduced when compared with wild-type neurons reaching the levels observed nonsynaptically (Fig. 4 and Table 1). The diffusion rate was not changed compared with diffusion rate in postsynaptic regions in wild-type neurons (Table 1). Hence, whereas the flux of the extrasynaptic NCAM180 to the postsynaptic regions was not changed, immobilization of NCAM180GFP in the postsynaptic membrane was reduced in the absence of homophilic interactions.

Interactions with the Spectrin Cytoskeleton Promote Immobilization of NCAM180GFP in the Postsynaptic Membrane

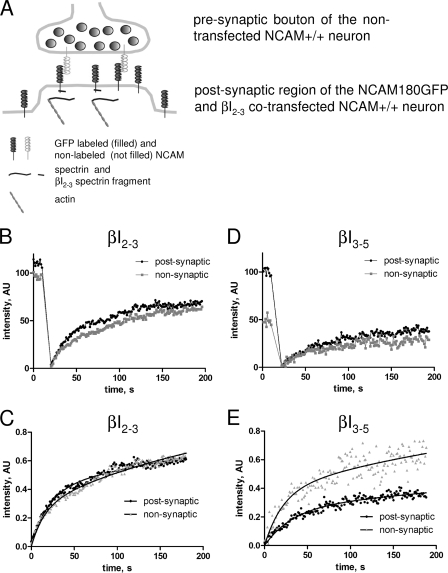

Because NCAM180 binds to the postsynaptic spectrin scaffold (25), we also analyzed whether this interaction plays a role in immobilization of NCAM180 in the postsynaptic membrane. Two experiments were performed.

First, we performed FRAP experiments in which this interaction was disrupted by co-transfecting wild-type hippocampal neurons with the spectrin fragment βI2–3 containing the NCAM binding site and disrupting the association between NCAM180 and endogenous spectrin (35). For comparison, we analyzed neurons co-transfected with the βI3–5 spectrin fragment, which does not interact with the intracellular domain of NCAM180 (35). The preferential accumulation of NCAM180GFP in the postsynaptic membrane was reduced in neurons transfected with the βI2–3 spectrin fragment (compare prebleach levels in Fig. 5B; see Fig. 7), but not in neurons transfected with the βI3–5 spectrin fragment (compare prebleach levels in Fig. 5D; see Fig. 7). Analysis of the FRAP curves (Fig. 5) showed that the postsynaptic Kd/Kb was increased to the levels observed in nonsynaptic regions in βI2–3 co-transfected neurons, but not in neurons co-transfected with βI3–5 (Table 1), and that the immobile pool of postsynaptic NCAM180GFP was reduced to 48 ± 1.7% of the total pool of NCAM180GFP in βI2–3 co-transfected neurons compared with 71 ± 3.0% of the total pool of NCAM180GFP in βI3–5 co-transfected neurons. NCAM180GFP diffusion rates were not changed in neurons co-transfected with any spectrin fragments when compared with wild-type neurons, which were not transfected with spectrin fragments (Table 1).

FIGURE 5.

Examples of FRAP experiments with NCAM+/+ neurons transfected with βI2–3 or βI3–5 spectrin fragments. A, scheme of molecular interactions between postsynaptic NCAM180GFP and synaptic scaffold in βI2–3 co-transfected neurons. NCAM180GFP can be either free or in a complex with presynaptic NCAM. Its interaction with postsynaptic intracellular spectrin is blocked by the βI2–3 spectrin fragment. For simplicity, endogenous postsynaptic NCAM180 is not shown. B and D, examples of FRAP measurements in the postsynaptic (black) and nonsynaptic (gray) regions of βI2–3 or βI3–5 transfected neurons. C and E, recovery curves from B and D normalized to prebleach NCAM180GFP levels. Note that NCAM180GFP fluorescence recovers to similar levels in the nonsynaptic and postsynaptic regions of the βI2–3 transfected neuron. Approximation curves used to calculate diffusion rates and Kd/Kb are shown as solid lines.

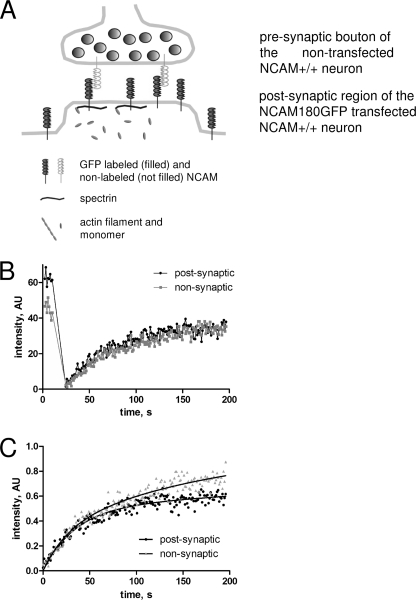

In a second set of experiments, we analyzed FRAP of NCAM180GFP in the postsynaptic membrane after disruption of actin microfilaments, with which the spectrin meshwork is associated. Actin microfilaments were disrupted by incubating wild-type hippocampal neurons for 2 h with the actin filament disrupting agent latrunculin (31) (Fig. 6A). Incubation with latrunculin resulted in dispersion of actin filaments as confirmed by staining of neurons with fluorescent phalloidin (not shown). Analysis of NCAM180GFP FRAP curves in neurons treated with latrunculin (Fig. 6) showed that Kd/Kb of NCAM180GFP in postsynaptic regions of latrunculin-treated neurons was increased to the levels of nonsynaptic regions (Table 1), whereas the size of the immobile pool of postsynaptic NCAM180GFP declined to 50 ± 2.4% of the total pool of NCAM180GFP. The preferential accumulation of NCAM180GFP in the postsynaptic membrane was reduced in neurons treated with latrunculin (compare prebleach levels in Fig. 6; see also Fig. 7). Latrunculin treatment did not affect diffusion rates of NCAM180GFP both in nonsynaptic and synaptic regions of dendrites (Table 1). Our data thus indicate that the postsynaptic cytoskeleton promotes immobilization of NCAM180 in the postsynaptic membrane and does not influence the flux of NCAM180GFP to the postsynaptic membrane from extrasynaptic regions.

FIGURE 6.

Example of a FRAP experiment with NCAM+/+ neurons treated with latrunculin. A, scheme of molecular interactions between postsynaptic NCAM180GFP and synaptic scaffold in latrunculin-treated neurons. NCAM180GFP can be either free or in a complex with presynaptic NCAM, postsynaptic intracellular spectrin, or both (shown from the right to the left in the synapse). Latrunculin disrupts the attachment of the spectrin meshwork to actin microfilaments. For simplicity, endogenous postsynaptic NCAM180 is not shown. B, example of FRAP measurements in the postsynaptic (black) and nonsynaptic (gray) regions from one experiment. C, recovery curves from B normalized to prebleach NCAM180GFP levels. Approximation curves used to calculate diffusion rates and Kd/Kb are shown as solid lines.

DISCUSSION

Adhesion molecules are indispensable components of synapses that play a role not only in synapse formation and stabilization but also in regulation of synapse functioning after maturation (4, 6, 33, 34, 36). The neural cell adhesion molecule NCAM and, in particular, its largest NCAM180 isoform, is one of such components (14, 25). Delivery of adhesion molecules to nascent synapses during development or to activated synapses during induction of long term potentiation was described as quantal, i.e. adhesion molecules are delivered in clusters either at the cell surface or inside of organelles (9, 12, 13, 27), as was also observed for postsynaptic glutamate receptors (37, 38). During development or synapse activation, these mechanisms can provide a rapid stepwise increase in the density of adhesion molecules at a nascent synaptic contact required for contact stabilization.

In mature neurons at the steady state, synaptic adhesion molecules not only maintain structural stability of synaptic contacts but also regulate overall numbers of synapses and fine-tune synaptic signaling cascades, levels of other synaptic proteins, and even synaptic vesicle recycling (6, 14, 33, 34, 39, 40). Therefore, removal or delivery of a quantum of adhesion molecules from any given synapse may not only compromise the overall synapse stability but also change its properties. Such fluctuations in synapse stability have not, however, been documented with the lifespan of an individual synaptic contact in mature neurons being months or years (1, 3). These observations suggest that homeostatic mechanisms continuously replenishing synaptic pools of adhesion molecules exist.

The lifespan of an individual NCAM protein molecule is up to several days (41, 42), indicating that the synaptic pool of NCAM must also be replenished. Based on our present data, we propose that the replenishment of postsynaptic NCAM180 occurs via a continuous flux of freely diffusible NCAM180 from the extrasynaptic membrane to the postsynaptic membrane. These data are in agreement with earlier observations showing that NCAM molecules are mobile in the cell surface membrane of different cell types (43–46). We now show that the freely diffusible pool of NCAM180 in the neuronal cell surface membrane intermixes not only with the mobile pool of NCAM180 in synapses but also with the immobile synaptic pool of NCAM albeit at slower pace.

The immobile pool of NCAM180 in synapses is the pool presumably responsible for NCAM-mediated stabilization of synaptic contacts. The fact that there is a continuous exchange between this pool and the pool of freely diffusible NCAM180 poses the question regarding the mechanisms that maintain immobilization of NCAM180 in the postsynaptic membrane. The cytoskeleton, homophilic interactions of NCAM, and modifications of its extracellular domain were shown to influence the mobility of NCAM in the plasma membrane of heterologous cells (43–45). Binding to synaptic scaffold proteins is often considered as a mechanism for the recruitment of proteins to synapses (47). The intracellular domain of NCAM directly interacts with the spectrin scaffold accumulating in synapses (25, 35). The extracellular domain of NCAM binds to the extracellular domains of NCAM molecules on adjacent membranes, thereby mediating homophilic cell adhesion interactions (48). In the present study, we found that disruption of the association of NCAM180 with the cytoskeleton reduces its accumulation in the postsynaptic membrane. A reduction in the levels of NCAM180 is accompanied by an increase in the pool of free NCAM180 molecules but not by changes in the overall mobility of NCAM180. Similarly, accumulation of NCAM180 in the postsynaptic membrane is reduced in the absence of its homophilic interactions with NCAM on the presynaptic membrane and is accompanied by an increase in the mobile pool rather than changes in the mobility of NCAM180 in the postsynaptic membrane. Altogether, our data suggest that the synaptic scaffold plays a major role in promoting the accumulation of NCAM in synapses by providing sites for binding of NCAM molecules. Moreover, both homophilic interactions of NCAM and its binding the cytoskeleton are required for the accumulation of NCAM180 in the postsynaptic membrane. The synaptic scaffold does not, however, significantly influence the overall mobility of freely diffusible NCAM molecules in the postsynaptic membrane, which may be important for the efficient continuous replenishment of the immobilized pool of synaptic NCAM180.

Interestingly, the diffusion of NCAM180 has been shown previously to be reduced at sites of contacts between 3T3 cells transfected with NCAM180, whereas the size of the mobile fraction of NCAM180 was unchanged at contacts versus noncontact sites in these cells (44). This observation appears to be in contrast to our findings and suggests that the mechanisms regulating accumulation of NCAM in the synaptic membranes are different from those promoting accumulation of NCAM at sites of contact between non-neuronal cells. In agreement with our findings, differentiation of neuroblastoma N2A cells in culture was accompanied by a significant increase in the size of the immobile pool of NCAM rather than changes in its diffusion rates (45).

The levels of NCAM180 in the postsynaptic membrane increase after induction of long term potentiation (27, 49). It is likely that NCAM180 is delivered to the activated synapses in intracellular organelles as it has been shown for neuroligins (13) and AMPA receptors (37, 50, 51). In addition, our data suggest that an increase in the homophilic interactions of NCAM180 or its binding to the spectrin cytoskeleton can also promote immobilization of NCAM180 in activated synapses. In agreement with this idea, synaptic activity is accompanied by cell surface delivery of NCAM from intracellular organelles (52) and may therefore increase its homophilic interactions. Clustering of NCAM induces the assembly of the spectrin meshwork (25, 35), which in turn may promote the retention of NCAM180 at activated synapses. Furthermore, although the interaction of NCAM180 with spectrin is not Ca2+-dependent (53), synaptic activity-induced Ca2+ influx induces redistribution to and immobilization in synapses of CaMKIIα (54–56), which binds to the NCAM-spectrin complex (25) and may thus also increase the interactions between NCAM and the cytoskeleton. The interaction between NCAM and CaMKIIα can also be enhanced by calmodulin, which binds to NCAM in a Ca2+-dependent manner (57).

The fact that a substantial fraction of NCAM180 in the postsynaptic membrane resides in the freely diffusible pool suggests that the functions of this pool are not limited to the delivery of newly synthesized NCAM180 molecules to synapses. The freely diffusible pool of NCAM180 can serve as a source of NCAM180 stabilizing nano-scale changes in the postsynaptic membranes of synapses, such as occurring during restructuring of the cytoskeleton, which also has to be replenished with a new protein. Mobility of NCAM has also been linked to its capability to induce intracellular signaling cascades, which depend on the dynamic redistribution of NCAM to lipid rafts and association with cell surface-localized receptors and signal transducers (53, 58–60). It is conceivable that this feature of NCAM would be reduced by a rigid association of NCAM with the cytoskeleton. Hence, the mobile pool of NCAM can serve as a signaling component in the postsynaptic membrane. Indeed, reduced activation of CaMKIIα, FGF receptor, and cAMP-responsive element-binding protein signaling pathways has been found in the brains of NCAM-deficient mice (25, 61, 62). Whether changes in the mobile pool of NCAM in activated synapses can modulate synaptic signaling cascades is an interesting question for future analysis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ute Eicke-Kohlmorgen, Achim Dahlmann, and Eva Kronberg for technical assistance, genotyping, and animal care. We thank Dr. Harold Cremer for NCAM−/− mice.

This work was supported by funds from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to M. S., I. L., and V. S.) and the National Health and Medical Research Council (to V. S.).

- NCAM

- neural cell adhesion molecule

- CaMKIIα

- Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase α

- FRAP

- fluorescence recovery after photobleaching.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zuo Y., Lin A., Chang P., Gan W. B. (2005) Neuron 46, 181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu S. H., Arévalo J. C., Sarti F., Tessarollo L., Gan W. B., Chao M. V. (2009) Dev. Neurobiol. 69, 547–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grutzendler J., Kasthuri N., Gan W. B. (2002) Nature 420, 812–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams M. E., de Wit J., Ghosh A. (2010) Neuron 68, 9–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chua J. J., Kindler S., Boyken J., Jahn R. (2010) J. Cell Sci. 123, 819–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dalva M. B., McClelland A. C., Kayser M. S. (2007) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 206–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Südhof T. C. (2008) Nature 455, 903–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomas U., Kobler O., Gundelfinger E. D. (2010) J. Neurogenet. 24, 109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mendez P., De Roo M., Poglia L., Klauser P., Muller D. (2010) J. Cell Biol. 189, 589–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhai R. G., Vardinon-Friedman H., Cases-Langhoff C., Becker B., Gundelfinger E. D., Ziv N. E., Garner C. C. (2001) Neuron 29, 131–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gerrow K., Romorini S., Nabi S. M., Colicos M. A., Sala C., El-Husseini A. (2006) Neuron 49, 547–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sytnyk V., Leshchyns'ka I., Delling M., Dityateva G., Dityatev A., Schachner M. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 159, 649–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schapitz I. U., Behrend B., Pechmann Y., Lappe-Siefke C., Kneussel S. J., Wallace K. E., Stempel A. V., Buck F., Grant S. G., Schweizer M., Schmitz D., Schwarz J. R., Holzbaur E. L., Kneussel M. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 12733–12744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dityatev A., Dityateva G., Sytnyk V., Delling M., Toni N., Nikonenko I., Muller D., Schachner M. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 9372–9382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bukalo O., Fentrop N., Lee A. Y., Salmen B., Law J. W., Wotjak C. T., Schweizer M., Dityatev A., Schachner M. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 1565–1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stork O., Welzl H., Wotjak C. T., Hoyer D., Delling M., Cremer H., Schachner M. (1999) J. Neurobiol. 40, 343–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stork O., Welzl H., Wolfer D., Schuster T., Mantei N., Stork S., Hoyer D., Lipp H., Obata K., Schachner M. (2000) Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 3291–3306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stork O., Welzl H., Cremer H., Schachner M. (1997) Eur. J. Neurosci. 9, 1117–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Becker C. G., Artola A., Gerardy-Schahn R., Becker T., Welzl H., Schachner M. (1996) J. Neurosci. Res. 45, 143–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stoenica L., Senkov O., Gerardy-Schahn R., Weinhold B., Schachner M., Dityatev A. (2006) Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 2255–2264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Muller D., Wang C., Skibo G., Toni N., Cremer H., Calaora V., Rougon G., Kiss J. Z. (1996) Neuron 17, 413–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Atz M. E., Rollins B., Vawter M. P. (2007) Psychiatr. Genet. 17, 55–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arai M., Itokawa M., Yamada K., Toyota T., Arai M., Haga S., Ujike H., Sora I., Ikeda K., Yoshikawa T. (2004) Biol. Psychiatry 55, 804–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sullivan P. F., Keefe R. S., Lange L. A., Lange E. M., Stroup T. S., Lieberman J., Maness P. F. (2007) Biol. Psychiatry 61, 902–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sytnyk V., Leshchyns'ka I., Nikonenko A. G., Schachner M. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 174, 1071–1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Persohn E., Pollerberg G. E., Schachner M. (1989) J. Comp. Neurol. 288, 92–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schuster T., Krug M., Hassan H., Schachner M. (1998) J. Neurobiol. 37, 359–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kochlamazashvili G., Senkov O., Grebenyuk S., Robinson C., Xiao M. F., Stummeyer K., Gerardy-Schahn R., Engel A. K., Feig L., Semyanov A., Suppiramaniam V., Schachner M., Dityatev A. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 4171–4183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Westphal D., Sytnyk V., Schachner M., Leshchyns'ka I. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 42046–42057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cremer H., Lange R., Christoph A., Plomann M., Vopper G., Roes J., Brown R., Baldwin S., Kraemer P., Scheff S., Barthels D., Rajewsky K., Wille W. (1994) Nature 367, 455–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Allison D. W., Chervin A. S., Gelfand V. I., Craig A. M. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 4545–4554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pollerberg G. E., Burridge K., Krebs K. E., Goodman S. R., Schachner M. (1987) Cell Tissue Res. 250, 227–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leshchyns'ka I., Sytnyk V., Richter M., Andreyeva A., Puchkov D., Schachner M. (2006) Neuron 52, 1011–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Andreyeva A., Leshchyns'ka I., Knepper M., Betzel C., Redecke L., Sytnyk V., Schachner M. (2010) PLoS One 5, e12018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leshchyns'ka I., Sytnyk V., Morrow J. S., Schachner M. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 161, 625–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schachner M. (1997) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9, 627–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Petrini E. M., Lu J., Cognet L., Lounis B., Ehlers M. D., Choquet D. (2009) Neuron 63, 92–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Newpher T. M., Ehlers M. D. (2009) Trends Cell Biol. 19, 218–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Robbins E. M., Krupp A. J., Perez de Arce K., Ghosh A. K., Fogel A. I., Boucard A., Südhof T. C., Stein V., Biederer T. (2010) Neuron 68, 894–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Biederer T., Sara Y., Mozhayeva M., Atasoy D., Liu X., Kavalali E. T., Südhof T. C. (2002) Science 297, 1525–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Keane R. W., Mehta P. P., Rose B., Honig L. S., Loewenstein W. R., Rutishauser U. (1988) J. Cell Biol. 106, 1307–1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Park T. U., Lucka L., Reutter W., Horstkorte R. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 234, 686–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Conchonaud F., Nicolas S., Amoureux M. C., Ménager C., Marguet D., Lenne P. F., Rougon G., Matarazzo V. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26266–26274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jacobson K. A., Moore S. E., Yang B., Doherty P., Gordon G. W., Walsh F. S. (1997) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1330, 138–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pollerberg G. E., Schachner M., Davoust J. (1986) Nature 324, 462–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Simson R., Yang B., Moore S. E., Doherty P., Walsh F. S., Jacobson K. A. (1998) Biophys. J. 74, 297–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kim E., Sheng M. (2004) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 771–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Soroka V., Kolkova K., Kastrup J. S., Diederichs K., Breed J., Kiselyov V. V., Poulsen F. M., Larsen I. K., Welte W., Berezin V., Bock E., Kasper C. (2003) Structure 11, 1291–1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fux C. M., Krug M., Dityatev A., Schuster T., Schachner M. (2003) Mol. Cell Neurosci. 24, 939–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shi S. H., Hayashi Y., Petralia R. S., Zaman S. H., Wenthold R. J., Svoboda K., Malinow R. (1999) Science 284, 1811–1816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kielland A., Bochorishvili G., Corson J., Zhang L., Rosin D. L., Heggelund P., Zhu J. J. (2009) Neuron 62, 84–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kiss J. Z., Wang C., Olive S., Rougon G., Lang J., Baetens D., Harry D., Pralong W. F. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 5284–5292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bodrikov V., Leshchyns'ka I., Sytnyk V., Overvoorde J., den Hertog J., Schachner M. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 168, 127–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sharma K., Fong D. K., Craig A. M. (2006) Mol. Cell Neurosci. 31, 702–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Otmakhov N., Tao-Cheng J. H., Carpenter S., Asrican B., Dosemeci A., Reese T. S., Lisman J. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 9324–9331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Merrill M. A., Chen Y., Strack S., Hell J. W. (2005) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26, 645–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kleene R., Mzoughi M., Joshi G., Kalus I., Bormann U., Schulze C., Xiao M. F., Dityatev A., Schachner M. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 10784–10798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bodrikov V., Sytnyk V., Leshchyns'ka I., den Hertog J., Schachner M. (2008) J. Cell Biol. 182, 1185–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Niethammer P., Delling M., Sytnyk V., Dityatev A., Fukami K., Schachner M. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 157, 521–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Korshunova I., Novitskaya V., Kiryushko D., Pedersen N., Kolkova K., Kropotova E., Mosevitsky M., Rayko M., Morrow J. S., Ginzburg I., Berezin V., Bock E. (2007) J Neurochem 100, 1599–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Aonurm-Helm A., Berezin V., Bock E., Zharkovsky A. (2010) Brain Res. 1309, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Aonurm-Helm A., Zharkovsky T., Jürgenson M., Kalda A., Zharkovsky A. (2008) Brain Res. 1243, 104–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]