Abstract

While it is well accepted that Native Hawaiians have poor health statistics compared to other ethnic groups in Hawaii, it is not well documented if these disparities persist when comparing Native Hawaiian homeless individuals to the general homeless population. This paper examines the Native Hawaiian homeless population living in three shelters on the island of Oahu, to determine if there are significant differences in the frequency of diseases between the Native Hawaiian and non-Native Hawaiian homeless.

A retrospective data collection was performed using records from the Hawai‘i Homeless Outreach and Medical Education (H.O.M.E.) project. Data from 1182 patients was collected as of 12/05/09. Information collected included patient demographics, frequency of self reported diseases, family history of diseases, risk factors, prevalence of chronic diseases, and most common complaints. The data from Native Hawaiians and non-Native Hawaiians were examined for differences and a 1-tail Fisher exact analysis was done to confirm significance.

The data reveals that the Native Hawaiian homeless population is afflicted more frequently with asthma and hypertension compared to other ethnic groups. While diabetes constituted more visits to the clinics for Native Hawaiians compared to the non-Native Hawaiians, there was no significant difference in patient reported prevalence of diabetes. The Native Hawaiian homeless also had increased rates of risky behaviors demonstrated by higher past use of marijuana and methamphetamines. Interestingly, there was a lower use of alcohol in the Native Hawaiian homeless and no significant difference between Native Hawaiians and non-native Hawaiians in current use of illicit drugs, which may represent a hopeful change in behaviors.

These troubling statistics show that some of the health disparities seen in the general Native Hawaiian population persist despite the global impoverished state of all homeless. Hopefully, these results will aid organizations like the H.O.M.E. project to better address the health needs of the Native Hawaiian homeless population.

Introduction

On March 27, 2006 the city and county of Honolulu began a cleanup of Ala Moana Beach Park, which displaced approximately 200 homeless people.1 Many of these displaced individuals returned to the Waianae coast communities on the west shore where they originally came from.2 These individuals added to the large community of homeless already living on the west coast, or Leeward side, of O‘ahu. The beaches of the Waianae coast house homeless tent communities estimated to contain 1,000 – 4,000 individuals. While these numbers are large, they may not accurately account for the hidden homeless population of individuals who sleep with relatives, in cars, or at campsites that are not as visible as the beaches.2,3

In an effort to deal with this problem, emergency shelters were set up around the island of O‘ahu. The first was the Next Step Shelter at Kaka‘ako in March of 2006 followed by another transitional shelter at Kalealoa in October of 2006, located at the former Barbers Point Naval Air Station. Finally, to help curb the growing homelessness on the Leeward coast, construction began on November 18, 2006 for a 300 person emergency transitional shelter.1,2,4 Prior to this point, the two main shelters on O‘ahu were the Institute for Human Services' Men's Shelter and Women's and Children's Shelter, both located in downtown Honolulu.5

In recent years the healthcare needs of these homeless individuals living on the Leeward coast has increased. Waianae Coast Comprehensive Center is the main source of healthcare for Waianae coast residents, especially low-income individuals. The center saw a 234% rise in treated homeless individuals from 429 patients in 2003 to 1,002 in 2006 indicating that there was a growing demand for these services.6

In an effort to help provide quality medical care to the growing number of homeless in Hawai‘i, the Hawai‘i Homeless Outreach and Medical Education (H.O.M.E.) project was established as part of the John A. Burns School of Medicine (JABSOM). The program provides free weekly medical care to the homeless at three shelters on O‘ahu. Their mission is to “improve quality and access to health care for Hawai‘i's homeless, while increasing student and physician awareness and understanding of the homeless and their healthcare needs.” The project currently provides a free student-run clinic at the Kaka‘ako Next Step Shelter, Pai‘olu Kaiaulu Shelter in Waianae, and Onemalu and Onelauena Shelters in Kalaeloa.7

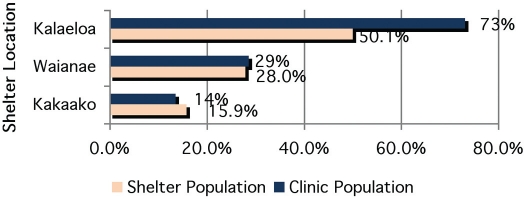

The Waianae coast community is predominately made up of low-income individuals, many of whom are Native Hawaiian. As of August 2006, 60–70% of the Waianae homeless were Native Hawaiian and 700 were children under the age of 18.3 In addition to making up a large proportion of the Leeward coast homeless population, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders are generally overrepresented in lower socio-economic groups.8 In the county of Honolulu, Native Hawaiians made up 16.1% of the general population.8 While Native Hawaiians are similarly represented at the Kaka‘ako shelter (15.9%), they are overrepresented in both the Waianae and Kalaeloa shelters (28.0% and 50.1% respectively).10–12 (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

% of Native Hawaiians in Clinic Population vs. Shelter Population

In 1988 the Native Hawaiian Health Care improvement Act established programs to improve the health status of Native Hawaiians.13 The Native Hawaiian Health Care Systems Program attempts to improve the health status of Native Hawaiians by increasing health education, health promotion, and preventative medicine with programs like Papa Ola Lokahi. Papa Ola Lokahi (POL) was formed in 1988 to address the health care needs of the Native Hawaiian people. A not-for-profit charitable consortium organization, it serves as an umbrella for Native Hawaiian health care planning activities in the state. Such activities are coordinating health care programs for Native Hawaiians and the Native Hawaiian Health Care program, which also supports scholarships to Native Hawaiians in health professions.8

Despite efforts to improve the health of the Native Hawaiian people, their health status is one of the poorest in the nation, suffering from disproportionately high rates of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, cancers, diabetes, obstructive lung diseases (asthma, bronchitis, emphysema), chronic kidney disease, metabolic syndrome, and obesity, with the highest rate of diabetes amongst ethnic subgroups in Hawai‘i. Native Hawaiians also have a lower life expectancy and higher rates of cardiovascular and diabetes related mortality. Additionally, Native Hawaiians have more behavioral risk factors for diseases, with higher rates of tobacco use, alcohol consumption, methamphetamine use, and dietary fat intake, compounded by lower fruit/vegetable intake, and decreased physical activity. Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders also have lower preventative medicine practices (e.g. cancer screenings) and report greater difficulty in obtaining healthcare.8,13–18 Some of the proposed barriers to improving the health of the Native Hawaiian people are believed to be related to cultural, financial, social and geographic barriers which prevent the utilization of existing health services.8

Given the poor health status of the Native Hawaiian people and the rising healthcare needs of the homeless, especially on the Leeward coast where there is a large proportion of Native Hawaiians, this study aims to determine if there are any health disparities in the Native Hawaiian homeless population compared to the rest of the shelter residents. In this study, we anticipated that Native Hawaiian homeless, like the Native Hawaiian population outside of the shelter, would have poorer health status than the other ethnic groups. The authors also hoped to identify which health problems are most prevalent amongst the Native Hawaiian homeless. If disparities exist between the Native Hawaiian homeless and non-Native Hawaiian populations we hope that this study can be used in order to justify better care for this population through services like the H.O.M.E. project and other clinics that provide care to this population.

Methods

The University of Hawai‘i's Institutional Review Board (IRB) granted approval for this study. A retrospective chart review was performed on the patients seen at the Hawai‘i H.O.M.E. project's free medical clinics. As of 12/05/09, 1182 charts were reviewed which represent the clinics active patient population since its inception on May 30, 2006. The data from intake forms and patient progress notes was de-identified, compiled, categorized and analyzed to determine the occurrence of diseases within the Native Hawaiian homeless population compared to the non-Hawaiian homeless population. For each patient, the self-reported ethnicity, age, sex, medical history, and family history of diseases on the intake forms were reviewed along with the progress note assessment and plan for visit diagnoses.

The items listed on the self reported medical history on the intake forms for both adults and children are found in Table 3 and 4. Pediatric patients are defined as being 17 years or younger. The self reported intake forms also ask about family history (Tables 5–7) and risk factors (Table 10).

Table 3.

Patient Reported Medical Conditions - Adults

| Disease | Native Hawaiians | % | Non-Native Hawaiians | % |

| Acquired Hypothyroid | 5 | 1.8% | 4 | 0.7% |

| Anemia | 16 | 5.6% | 18 | 3.3% |

| Angina | 2 | 0.7% | 2 | 0.4% |

| Asthma | 57 | 20.1% | 74 | 13.5% |

| Bipolar disorder | 6 | 2.1% | 7 | 1.3% |

| Breast CA | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.2% |

| Cataracts | 8 | 2.8% | 13 | 2.4% |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 | 0.4% | 4 | 0.7% |

| Chicken Pox | 128 | 45.1% | 209 | 38.2% |

| Chronic Back Pain | 29 | 10.2% | 64 | 11.7% |

| Cirrhosis | 1 | 0.4% | 3 | 0.5% |

| Colon CA | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.4% |

| Coronary Artery Dz | 2 | 0.7% | 10 | 1.8% |

| Depression | 17 | 6.0% | 31 | 5.7% |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 26 | 9.2% | 57 | 10.4% |

| Emphysema | 1 | 0.4% | 7 | 1.3% |

| Essential hypertension | 51 | 18.0% | 102 | 18.6% |

| Fractures | 25 | 8.8% | 34 | 6.2% |

| GERD | 17 | 6.0% | 45 | 8.2% |

| Glaucoma | 1 | 0.4% | 1 | 0.2% |

| Gonorrhea | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 0.7% |

| Heart failure | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.4% |

| Hepatitis A | 1 | 0.4% | 3 | 0.5% |

| Hepatitis B | 1 | 0.4% | 8 | 1.5% |

| Hepatitis C | 0 | 0.0% | 14 | 2.6% |

| HIV and/or AIDS | 2 | 0.7% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Hyperlipidemia | 16 | 5.6% | 25 | 4.6% |

| Hyperthyroid | 2 | 0.7% | 7 | 1.3% |

| Measles | 44 | 15.5% | 73 | 13.3% |

| Melanoma | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.2% |

| Migraine | 1 | 0.4% | 3 | 0.5% |

| Mumps | 34 | 12.0% | 59 | 10.8% |

| Osteoarthritis | 5 | 1.8% | 34 | 6.2% |

| Peripheral Vascular disease | 1 | 0.4% | 5 | 0.9% |

| Polio | 3 | 1.1% | 2 | 0.4% |

| Renal failure | 1 | 0.4% | 6 | 1.1% |

| Rheumatic Fever | 4 | 1.4% | 3 | 0.5% |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 9 | 3.2% | 25 | 4.6% |

| Rubella | 1 | 0.4% | 1 | 0.2% |

| Scarlet Fever | 1 | 0.4% | 3 | 0.5% |

| Schizophrenia | 2 | 0.7% | 4 | 0.7% |

| Seizure disorder | 4 | 1.4% | 20 | 3.7% |

| Whooping Cough | 7 | 2.5% | 14 | 2.6% |

Table 4.

Patient Reported Medical Conditions - Pediatrics

| Disease | Native Hawaiians | % | Non-Native Hawaiians | % |

| Anemia | 3 | 2.6% | 1 | 0.5% |

| Asthma | 29 | 24.8% | 20 | 9.9% |

| Chicken Pox | 4 | 3.4% | 17 | 8.4% |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.5% |

| Fractures | 3 | 2.6% | 7 | 3.5% |

| Hepatitis A | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.5% |

| Measles | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.5% |

| Mumps | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 1.0% |

| Seizure disorder | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.5% |

| Whooping Cough | 2 | 1.7% | 0 | 0.0% |

Table 5.

Family History in Mother

| Disease | Native Hawaiians | % | Non-Native Hawaiians | % |

| Alcoholism | 39 | 9.7% | 20 | 2.7% |

| Allergies | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Asthma | 49 | 12.2% | 42 | 5.6% |

| Breast CA | 12 | 3.0% | 10 | 1.3% |

| Coronary artery disease | 3 | 0.7% | 7 | 0.9% |

| Depression | 8 | 2.0% | 13 | 1.7% |

| Diabetes | 70 | 17.5% | 91 | 12.1% |

| Heart attack | 36 | 9.0% | 34 | 4.5% |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Hypertension | 68 | 17.0% | 106 | 14.2% |

| Other CA | 56 | 14.0% | 47 | 6.3% |

| Schizophrenia | 4 | 1.0% | 4 | 0.5% |

| Stroke | 36 | 9.0% | 41 | 5.5% |

| Thyroid problems | 1 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% |

Table 7.

Family History in Sibling

| Disease | Native Hawaiians | % | Non-Native Hawaiians | % |

| Alcoholism | 16 | 4.0% | 22 | 2.9% |

| Allergies | 2 | 0.5% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Asthma | 40 | 10.0% | 37 | 4.9% |

| Breast CA | 5 | 1.2% | 7 | 0.9% |

| Coronary artery disease | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 0.4% |

| Depression | 1 | 0.2% | 4 | 0.5% |

| Diabetes | 15 | 3.7% | 43 | 5.7% |

| Heart attack | 7 | 1.7% | 16 | 2.1% |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Hypertension | 11 | 2.7% | 35 | 4.7% |

| Other CA | 6 | 1.5% | 25 | 3.3% |

| Stroke | 5 | 1.2% | 17 | 2.3% |

| Thyroid problems | 1 | 0.2% | 1 | 0.1% |

Table 10.

Risk Factors

| Risk factor | Native Hawaiians | % | Non-Native Hawaiians | % |

| Tobacco use (lifetime) | 125 | 31.2% | 223 | 29.8% |

| Current tobacco use | 108 | 26.9% | 170 | 22.7% |

| Average pack years | 20.25 (n=88) | — | 22.96 (n=160) | — |

| Alcohol use | 29 | 7.2% | 91 | 12.1% |

| Average drinks per day | 4.94 (n =19) | — | 3.75 (n= 60) | — |

| History of excessive drinking | 8 | 2.0% | 29 | 3.8% |

| Ever used marijuana | 49 | 12.2% | 47 | 6.3% |

| Current marijuana use | 11 | 2.7% | 20 | 2.7% |

| Ever used methamphetamines | 47 | 11.7% | 38 | 5.1% |

| Current methamphetamine use | 8 | 2.0% | 6 | 0.8% |

| Ever used cocaine | 17 | 4.2% | 18 | 2.4% |

| Current Cocaine use | 3 | 0.7% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Ever used heroin | 4 | 1.0% | 6 | 0.8% |

| Current heroin use | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Victim of domestic violence | 25 | 6.2% | 33 | 4.4% |

| Current victim of domestic violence | 9 | 2.2% | 8 | 1.0% |

| Sexually active | 87 | 21.7% | 144 | 19.2% |

| Condom use (of sexually active) | 6 | 6.9% | 20 | 13.9% |

| Some form of contraception | 21 | 24.1% | 42 | 29.2% |

| Average # of sexual partners | 6.71 (n=69) | 5.14 (n=122) |

During the initial clinic visit, the clinic provider reviews the medical history intake form with the patient or the patient's parent - in the case of pediatric patients. The clinic providers are primarily third year medical students in their family medicine rotation who perform the medical history under the supervision of an attending faculty physician at JABSOM. After each clinic visit the student completes a progress note, with a complete assessment, plan, and medical diagnoses. The attending faculty physician reviews and cosigns all patient progress notes. From these notes the final diagnosis is made from the “Assessment and Plans” section. This data was used to compile a list of the most common ailments, and the prevalence of chronic medical conditions in the homeless population.

The data was examined for differences between the two populations and when differences were evident a 1-tail Fisher exact analysis was done to confirm significance; for purposes of this study a p-value cutoff of 0.05 is deemed significant.

Results

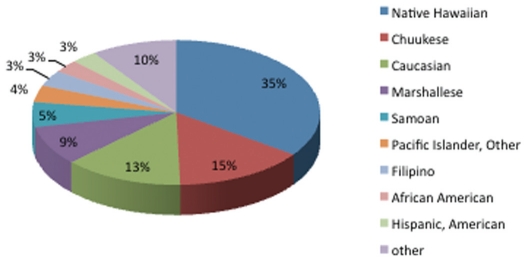

From 1182 charts, 32 were excluded for lack of a provider interview. Although they had registered at the clinic, a follow-up interview by a provider was not performed to complete the history intake form. Therefore, 1150 charts were included in the final analysis, 401 of which were identified as belonging to the Native Hawaiian group. (Table 1) Native Hawaiians represent the largest ethnic group seen in the clinic, comprising 34.9% of the patients seen, followed by Chuukeese (14.7%), Caucasian (13.4%), and Marshallese (8.8%). (Table 2 and Figure 1,2)

Table 1.

Patient Demographics of the H.O.M.E. Clinic

| Native Hawaiians | Other Ethnicity | Total | |

| Number of patients | 404 | 778 | 1182 |

| Number of Patients seen by provider | 401 | 749 | 1150 |

| Number registered but did not see a provider | 3 | 29 | 32 |

| Sex of Patient | |||

| Male | 181 | 381 | 562 |

| Female | 220 | 368 | 588 |

| Age | |||

| Mean age | 28 | 31 | |

| Median age | 28 | 34 | |

| Age range | 0–77 | 0–81 | |

| Total number of pediatric patients (17 or younger) | 119 | 203 | 322 |

| Male | 55 | 103 | 158 |

| Female | 64 | 100 | 164 |

| Kaka‘ako Shelter | 267 | 1325 | 1592 |

| Waianae Shelter | 727 | 664 | 1391 |

| Kalaeloa Shelter | 178 | 130 | 308 |

Table 2.

Ethnicities of the H.O.M.E Clinic Patients

| Ethnicity | Male | Female | Total | % of pop |

| Native Hawaiian | 181 | 220 | 401 | 34.9% |

| African American | 16 | 17 | 33 | 2.9% |

| American Indian | 8 | 14 | 22 | 1.9% |

| Asian Other | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.3% |

| Cambodian | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.1% |

| Caucasian | 104 | 50 | 154 | 13.4% |

| Chamorro | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.1% |

| Chinese | 2 | 5 | 7 | 0.6% |

| Chuukese | 69 | 100 | 169 | 14.7% |

| Filipino | 28 | 13 | 41 | 3.6% |

| Hispanic American | 18 | 15 | 33 | 2.9% |

| Hispanic European | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0.6% |

| Japanese | 12 | 3 | 15 | 1.3% |

| Korean | 1 | 4 | 5 | 0.4% |

| Kosraean (KS087) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.1% |

| Laotian | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.2% |

| Marshallese | 39 | 62 | 101 | 8.8% |

| Mixed ethnicity | 8 | 3 | 11 | 1.0% |

| Pacific islander, other | 21 | 22 | 43 | 3.7% |

| Pohnpeian | 7 | 10 | 17 | 1.5% |

| Portugese | 3 | 7 | 10 | 0.9% |

| Samoan | 33 | 31 | 64 | 5.6% |

| Tongan | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.2% |

| Vietnamese | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0.6% |

| Total | 562 | 588 | 1150 | 100.0% |

From the patient reported illnesses in the adult population there is a higher occurrence of asthma (20.1% vs. 13.5%; p-value 0.01) in the Native Hawaiian population. There was no significant difference between the occurrence of self-reported diabetes (9.2% vs. 10.4%; p-value 0.33) or hypertension (18.0% vs. 18.6%; p-value 0.44) in Native Hawaiians compared to other ethnicities. (Table 3) From the patient reported illnesses in the pediatric population, there is also a higher occurrence of asthma in Native Hawaiians (24.8% vs. 9.9%; p-value 4.3x104). (Table 4)

The data from the self reported family history shows a higher occurrence of asthma in the Native Hawaiians at 12.2% vs. 5.6%, 5.7% vs. 3.1%, and 10.0% vs. 4.9% (p-values of 8.6×10−5, 0.022 and 0.001) in the history of the patient's mother, father, and siblings respectively. Native Hawaiians also had a higher percentage of individuals with a family history of alcoholism in their parents (9.7% vs. 2.7% in mothers and 11.2% vs. 5.7% in fathers; p-values 5.2×10−7 and 0.0008), diabetes in their parents (17.5% vs. 12.1% in mothers and 14.0% vs. 8.4% in fathers; p-values 0.009 and 0.002), and a higher paternal history of hypertension (13.7% vs. 10.0%; p-value 0.038). (Tables 5–7)

The prevalence of chronic disease, calculated from the patient progress notes' “Assessment and Plan” section finds higher frequency of asthma (14.0% vs. 6.7%; p-value 5.2×10−5), and essential hypertension (13.7% vs. 9.1%; p-value 0.01) in Native Hawaiian homeless. There was no significant difference found in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus between Native Hawaiians and other ethnicities (7.5% vs. 5.2%; p-value 0.08). (Table 8)

Table 8.

Prevalence of Diseases

| Disease | Native Hawaiians | % | Non-Native Hawaiians | % |

| Allergic rhinitis | 11 | 2.7% | 24 | 3.2% |

| Anemia | 2 | 0.5% | 6 | 0.8% |

| Angina | 8 | 2.0% | 15 | 2.0% |

| Arrhythmia | 2 | 0.5% | 2 | 0.3% |

| Arteriosclerotic disease | 1 | 0.2% | 2 | 0.3% |

| Asthma | 56 | 14.0% | 50 | 6.7% |

| Back Pain | 15 | 3.7% | 42 | 5.6% |

| Bipolar | 2 | 0.5% | 11 | 1.5% |

| Cardiomyopathy | 2 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.1% |

| COPD | 7 | 1.7% | 6 | 0.8% |

| Depression | 14 | 3.5% | 21 | 2.8% |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 30 | 7.5% | 39 | 5.2% |

| Drug dependence | 2 | 0.5% | 4 | 0.5% |

| Dysmenorrhea/Amenorrhea | 11 | 2.7% | 18 | 2.4% |

| Eczema/atopic dermatitis | 16 | 4.0% | 34 | 4.5% |

| GERD | 12 | 3.0% | 15 | 2.0% |

| Gout | 2 | 0.5% | 3 | 0.4% |

| Hyperlipidemia | 5 | 1.2% | 8 | 1.1% |

| Hypertension | 55 | 13.7% | 68 | 9.1% |

| Hypothyroid | 5 | 1.2% | 2 | 0.3% |

| Lung CA | 1 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Osteoarthritis | 7 | 1.7% | 22 | 2.9% |

| Other MS complaint | 23 | 5.7% | 59 | 7.9% |

| Peripheral Vascular disease | 1 | 0.2% | 5 | 0.7% |

| Pregnancy | 12 | 3.0% | 19 | 2.5% |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 | 0.2% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Schizophrenia | 3 | 0.7% | 1 | 0.1% |

| 401 | 749 |

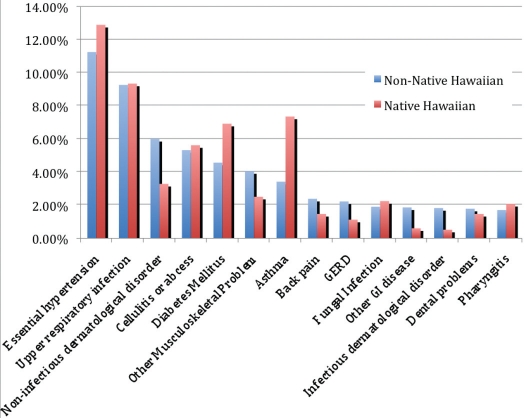

The Most Common Medical Visit Diagnoses data, extracted from the patient progress notes, finds that the most common complaints for both the Native Hawaiians and non-Native Hawaiians are essential hypertension and upper respiratory infection. The Native Hawaiian population, however, has a greater frequency of visits for asthma (7.4% vs. 3.4%; p-value 2.8×10−7) and diabetes mellitus (6.9% vs. 4.6%; p-value 0.002) when compared to the non-Native Hawaiian homeless.(Table 9 and Figure 3) Native Hawaiian clinic visits. While looking at risk factors, the Native Hawaiian homeless population was found to have a decreased current use of alcohol (7.2% vs. 12.1%, p-value 0.005) and an increased past use of both marijuana (12.2% vs. 6.3%; p-value 0.0005) and methamphetamine (11.7% vs. 5.1%; p-value 5.0×10−5) when compared with the rest of the homeless population. (Table 10)

Table 9.

Most Common Medical Visit Diagnoses - Total

| Native Hawaiian | Non-Native Hawaiian | |||

| Diagnosis/ problem | Number | % | Number | % |

| Essential Hypertension | 149 | 12.9% | 283 | 11.2% |

| Upper respiratory infection | 108 | 9.3% | 233 | 9.3% |

| Asthma | 85 | 7.4% | 86 | 3.4% |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 80 | 6.9% | 115 | 4.6% |

| Cellulitis or abscess | 65 | 5.6% | 134 | 5.3% |

| Non-infectious dermatological disorder | 38 | 3.3% | 151 | 6.0% |

| Musculoskeletal problem | 29 | 2.5% | 102 | 4.1% |

| Diarrhea | 28 | 2.4% | 37 | 1.5% |

| Fungal infection | 26 | 2.2% | 48 | 1.9% |

| Pharyngitis | 24 | 2.1% | 43 | 1.7% |

| Depression | 21 | 1.8% | 38 | 1.5% |

| Bronchitis | 19 | 1.6% | 27 | 1.1% |

| Dysmenorrheal/ Amenorrhea | 19 | 1.6% | 33 | 1.3% |

| Back pain | 17 | 1.5% | 60 | 2.4% |

| Dental problems | 17 | 1.5% | 45 | 1.8% |

| Eczema, Atopic Dermatitis | 17 | 1.5% | 34 | 1.4% |

| Otitis Media | 16 | 1.4% | 23 | 0.9% |

| Adult physical exam | 15 | 1.3% | 18 | 0.7% |

| GERD | 13 | 1.1% | 56 | 2.2% |

| Headache | 13 | 1.1% | 30 | 1.2% |

| Otitis Externa | 13 | 1.1% | 24 | 1.0% |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 13 | 1.1% | 19 | 0.8% |

| Allergic Rhinitis | 12 | 1.0% | 35 | 1.4% |

| GI disease | 7 | 0.6% | 47 | 1.9% |

| Infectious dermalogical disorder | 6 | 0.5% | 46 | 1.8% |

| Osteoarthritis | 6 | 0.5% | 28 | 1.1% |

| Total Number of Visits | 1156 | 2516 |

Figure 3.

Most Common Medical Visit Diagnoses

Discussion

Asthma and hypertension appear to afflict the Native Hawaiian homeless much more than the rest of the homeless population. There is a higher occurrence of asthma in both self-reported adult and pediatric populations and higher numbers of Native Hawaiians that have a family history of asthma. This is supported by a higher prevalence of asthma in the Native Hawaiian homeless found in the clinic database and it was also found to be one of the most common complaints bringing patients to the clinic, being third only after hypertension and URI. Asthma has been found to be twice as prevalent in the homeless compared to the general population, due to increased exposure to cigarette smoke, environmental pollutants, and other allergens.19 Given these statistics, we expected to find an increased prevalence of asthma in the Native Hawaiian homeless population, however, non-homeless Native Hawaiians have almost the same prevalence of asthma compared to the homeless clinic population (14% vs. 15.2%).20 This may be due to the fact that only sheltered homeless were included in this study and the numbers for unsheltered homeless may be higher. Despite the lack of an increase in the prevalence of asthma in homeless Native Hawaiians, the disparity between them and other ethnicities with asthma still persists.

Hypertension was found to be the most common chronic medical problem in both the Native Hawaiian and Non-Native Hawaiian homeless. However, similar to asthma, it was found to be more prevalent amongst the Native Hawaiian homeless compared to other ethnicities. Interestingly, the Native Hawaiian population did not self-report having a higher history of hypertension but did have a higher prevalence found during clinic visits. This could represent the fact that the Native Hawaiian patients were not aware of their condition and that it was being newly diagnosed by the H.O.M.E. clinics. This may also be the reason for a lower percentage of the Native Hawaiian homeless having hypertension compared to the general Native Hawaiian population (13.7% vs. 16.7%).20 Since hypertension is a “silent” disease and because the majority of the homeless do not seek “routine” medical care, it can be speculated that many homeless individuals with hypertension may not be getting diagnosed.

While the prevalence of diabetes in the general Native Hawaiian population is higher than other ethnicities, it was not found to be more prevalent in the Native Hawaiian homeless.20 Although there is limited published data documenting poor diets in the general homeless population, it is fairly well known that poverty is associated with both obesity and poor diets, high in polyunsaturated fats and simple carbohydrates, which would put all homeless individuals at risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus.21–23 However, it would be interesting to see if there was a difference in diabetes prevalence rates if the Native Hawaiian numbers were compared only to non-Pacific Islanders given that the Micronesian population probably has a similar prevalence of diabetes compared to the Native Hawaiian population, although data is lacking in this area. Despite the similar prevalence of diabetes amongst the clinic patients, Native Hawaiians did present to the clinics more for care of their diabetes. It is unclear if this indicates that Native Hawaiians required more visits to the clinics in order to manage their diabetes or if they were more diligent in addressing their medical problems. It would be interesting to look at diabetes in the homeless further to start to answer some of these questions.

The Native Hawaiian homeless also have a higher frequency of certain risky behaviors. They have a higher past use of drugs like marijuana and methamphetamines. These risk factors could have contributed to the current poor health status of the Native Hawaiian homeless as well as to their homelessness itself. There were no significant differences in the current use of illicit drugs amongst shelter residents and there was a lower prevalence of alcohol use amongst Native Hawaiians. This data could represent a hopeful improvement of behaviors in the Native Hawaiians. The data could be confounded by the shelter policies at the Pai‘olu Kaiaulu Shelter in Waianae, which strictly prohibits illicit drug use. Despite these drug policies, this represents a drop in current risky behaviors amongst the sheltered Native Hawaiian homeless and a first step toward improving their health status. There are certainly limitations to this study, foremost being that the data gathered is not from randomized homeless individuals, but rather only from sheltered homeless residents who sought care at one of the H.O.M.E. clinic sites. Additionally there may also be limitations on taking accurate family histories from non-native English speakers such as Chuukese and Marshallese patients when comparing prevalence rates. This data may not completely represent the unsheltered homeless or those that seek medical care elsewhere or not at all. Additionally, the data for the shelter demographics represents only a snapshot of the shelter populations at one point in time and it is difficult to represent the sheltered homeless population, as they are a transient population.

Even with its limitations, the study did demonstrate that despite the overall disadvantaged status of homelessness, Native Hawaiians are still at an increased risk of chronic diseases such as hypertension and asthma. Hopefully this information can help providers, like the H.O.M.E. project, to better serve the Native Hawaiian homeless population. Further studies would be warranted to look more closely at the specific chronic diseases in the Native Hawaiian homeless population, to examine the prevalence data in the unsheltered homeless, and to study the impact of providers like the H.O.M.E. project on the health of the homeless, in particular the Native Hawaiian homeless population.

Figure 2.

Ethnicities of H.O.M.E. Clinic Patients

Table 6.

Family History in Father

| Disease | Native Hawaiians | % | Non-Native Hawaiians | % |

| Alcoholism | 45 | 11.2% | 43 | 5.7% |

| Allergies | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Asthma | 23 | 5.7% | 23 | 3.1% |

| Coronary artery disease | 1 | 0.2% | 4 | 0.5% |

| Depression | 1 | 0.2% | 3 | 0.4% |

| Diabetes | 56 | 14.0% | 63 | 8.4% |

| Heart attack | 30 | 7.5% | 61 | 8.1% |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 | 0.2% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Hypertension | 55 | 13.7% | 75 | 10.0% |

| Other CA | 33 | 8.2% | 37 | 4.9% |

| Schizophrenia | 1 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Stroke | 19 | 4.7% | 22 | 2.9% |

| Thyroid problems | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.3% |

References

- 1.Kua Crystal. “City Had No Heart for Homeless, Gov Says: A City Official Notes the Ala Moana Effort Stirred the State to Act”. Honolulu Star Bulletin. Honolulu Star Bulletin, 2 May 2006. Web. 5 Jan. 2010. http://archives.starbulletin.com/2006/05/02/news/story04.html.

- 2.Magin Janis L. “Hawaii's Burgeoning Homeless Population Seeks Refuge on Beaches - Americas - International Herald Tribune.” The New York Times. The New York TImes, 5 Dec. 2006. Web. 5 Jan. 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/05/world/americas/05iht-hawaii.3784081.html.

- 3.Office Of Hawaiian Affairs. OHA Public Information Office, author. OHA Joins Governor's Effort to Find Solutions and Relief to Widespread Homelessness on Oahu's Leeward Coast. OHA Contributes to Homelessness Relief Efforts for Leeward Oahu. Office of Hawaiian Affairs, 7 Aug. 2006. Web. 5 Jan. 2010. http://www.oha.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=244&Itemid=166.

- 4.Hoover Will. “$34M to House Homeless.” Honolulu Advertiser. Honolulu Advertiser, 10 Dec. 2006. Web. 5 Jan. 2010. http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2006/Dec/10/ln/FP612100351.html.

- 5.Institute for Humane Services. Web. 24 April. 2010. http://www.ihshawaii.org.

- 6.Perez Rob. “Health Neglect Strains Main Medical Facility.” Honolulu Advertiser. Honolulu Advertiser, 21 Oct. 2006. Web. 5 Jan. 2010. http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2006/Oct/21/ln/FP610210347.html.

- 7.Hawaii H.O.M.E. Project | Homeless Outreach & Medical Education. Web. 05 Jan. 2010. http://www.hawaiihomeproject.org/index.html.

- 8.“Health Center Program: Special Populations”. Primary Health Care: Health Center Program HRSA. Web. 05 Jan. 2010. http://bphc.hrsa.gov/about/specialpopulations.htm.

- 9.Latest Population Estimate Data. State of Hawaii: Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism; 2009. “Latest Population Estimate Data Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism”. Web. 05 Jan. 2010. http://hawaii.gov/health/statististics/hhs/hhs_08/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Census data for Kakaako Next Step shelter (November 2009)

- 11.Census data for Waianae Pai'olu Kaiaulu shelter (February 2010)

- 12.Census data for Kalaeloa shelter (April 2009 – Februrary 2010

- 13.Blaisdell Richard K. 1995 Update on Kanaka Maoli (Indigenous Hawaiian) Health. Asian American and Pacific Islander Journal of Health. 1996;4.1–3:160–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mau Marjorie K. Cardiometabolic Health Disparities in Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders. Epidemiology Reviews. 2009;31:13–29. doi: 10.1093/ajerev/mxp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaisdell Richard K. The Health Status of the Kanaka Maoli. Asian American and Pacific Islander Journal of Health. 1993;1.2:116–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moy Karen L. Health Indicators of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders in the United States. Journal of Community Health. 2010;35.1:81–92. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9194-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mau Marjorie K. Risk factors associated with methamphetamine use and heart failure among Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Island peoples. Vascular Health and Risk Management. 2009;5(1):45–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dachs Gabi U. “Cancer disparities in indigenous Polynesian populations: Maori, Native Hawaiians, and Pacicific people”. Lancet Oncology. 2008;9(5):473–484. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70127-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zerger S. Chronic Medical Illness and Homeless Individuals: A Preliminary Review of the Literature. National Health Care for the Homeless Council; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawaii Health Survey 2008. Hawaii State Department of Health; http://www.nhchc.org/Publications/literaturereview_chronicillness.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friel S, Baker Pl. Equity, food security and health equity in the Asia Pacific region. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2009;18(4):620–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, Neckerman KM. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiol rev. 2009;31:7–20. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drewnowski A. “Obesity, diets, and social inequalities”. Nutr Rev. 2009 May;67(Suppl 1):S36–S39. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]