Abstract

Background

In this chart review, we attempted to evaluate the benefits of adding aripiprazole in veterans with military-related PTSD and comorbid depression, who had been minimally or partially responsive to their existing medications.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of patients who received an open-label, flexible-dose, 12- week course of adjunctive aripiprazole was conducted in 27 military veterans meeting DSM-IV criteria for PTSD and comorbid major depression. Concomitant psychiatric medications continued unchanged, except for other antipsychotics which were discontinued prior to initiating aripiprazole. The primary outcome variable was a change from baseline in the PTSD checklist-military version (PCL-M) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II).

Results

PTSD severity (Total PCL scores) decreased from 56.11 at baseline to 46.85 at 12-weeks (p < 0.0001 from Wilcoxon signed rank test) and the depression severity decreased from 30.44 at baseline to 20.67 at 12-weeks (p < 0.0001 from Wilcoxon signed rank test). Thirty seven percent (10/27) were considered responders, as defined by a decrease in total PCL scores of at least 20 percent and 19% (5/27) were considered as responders as defined by a decrease in total BDI score of at least 50%.

Conclusions

The addition of aripiprazole contributed to a reduction in both PTSD and depression symptomatology in a population that has traditionally demonstrated poor pharmacological response. Further investigations, including double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, are essential to confirm and further demonstrate the benefit of aripiprazole augmentation in the treatment of military related PTSD.

Background

Military-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a serious psychiatric condition often resulting from combat duty in the current wars in Afghanistan and Iraq [1] and past peacekeeping and humanitarian missions [2-4]. Patients with PTSD present with four symptom clusters: reexperiencing of the traumatic event(s), avoidance of reminders and emotional numbing (which are grouped together as one symptoms cluster in DSM-IV, but are seen as distinct and will likely be denoted as such in DSM-V), and hyperarousal symptoms [5,6]. Recent estimates of the prevalence of PTSD in various military and veteran populations have varied from a low of 4.8% in UK military members [7], to 10.3% in Canadian peacekeeping veterans, [8] and 11.2 - 17.1% in U.S. military members returning from the deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan [9]. Military-related PTSD is associated with severe psychosocial dysfunction [10,11].

The therapeutic response to pharmacological interventions for military-related PTSD is often disappointing [10,12-16]. PTSD often presents with co-morbidities such as depression and substance abuse or dependence [17,18]. Amongst veterans, the comorbidity rates may be much higher than in other populations [19,20]. Studies have also demonstrated that veterans with chronic, military-related PTSD often present with significant comorbid psychotic features [21,22] which may contribute to the severe psychosocial dysfunction in this population [10,11].

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and Selective Serotonin/Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) have the most empirical evidence for efficacy in the treatment of PTSD and are usually considered first-line treatment [5,16,23]. SSRIs and SNRIs are also effective agents for the treatment of co-morbid mood and anxiety disorders commonly associated with PTSD. However, the lack of efficacy of antidepressant monotherapy, especially in male combat veterans, [24,25] has led to the frequent use of combination strategies, especially the addition of antipsychotics, in many treatment guidelines for treatment-resistant PTSD [5,26].

The benefit of adding a second-generation antipsychotic, such as risperidone, quetiapine, or olanzapine for the treatment of PTSD in combination with a primary antidepressant has been suggested in numerous small studies, including a few randomized controlled trials [27-30]. These agents appear beneficial in managing hyperarousal symptoms such as hypervigilance and irritability, as well as severe dissociative symptoms [16]. There is also evidence for the addition of aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, and olanzapine for treatment-resistant depression, [31] which often presents as a complicating factor in military-related, chronic PTSD. More recently, the efficacy of aripiprazole in the treatment of PTSD has been demonstrated in three preliminary open-label studies in veteran populations, both as a monotherapy and as an adjunctive treatment [32-34].

Aripiprazole is a novel antipsychotic with partial agonist activity at D2 receptors and 5HT1A receptors, and antagonist activity at 5-HT2A receptors [35]. Aripiprazole is reported to have less risk for extrapyramidal side effects than traditional antipsychotics [36,37] and has been demonstrated to be effective in treatment-resistant depression [38,39].

Based on the positive results of aripiprazole for both treatment-resistant depression and treatment-resistant PTSD, and on its unique pharmacology, we hypothesized that aripiprazole would be efficacious for treatment-resistant military-related PTSD with comorbid major depression. To reflect general clinical practice, we conducted a retrospective file review to examine the benefits of adding aripiprazole in veterans with military-related PTSD and comorbid depression, who had been minimally or partially responsive to their existing medications. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to examine the efficacy of aripiprazole to treat both chronic PTSD and comorbid depression in a sample of veterans with chronic military-related PTSD where all of the participants had comorbid major depression.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants consisted of a sample of 27 out of 123 consecutive veterans who consented to try aripiprazole augmentation between November 2009 and August 2010. All patients were receiving outpatient psychiatric care at a clinic specializing in the assessment and treatment of military-related psychiatric conditions. The clinic follows a standardized assessment and treatment protocol; the standardized assessments included the PTSD Checklist-Military Version (PCL-M), [40] Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), [41] and Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), [42] administered at intake and at each follow-up appointment over the course of treatment. In addition to providing psychoeducation, the standard psychiatric treatment at the clinic includes symptom management, treatment of comorbid disorders, and management of functional impairment [5]. Participants were prescribed aripiprazole after demonstrating minimal or partial response to their existing antidepressant and/or minimal or partial response to other antipsychotic augmentation strategies. All subjects received a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation and laboratory tests (complete blood count with white count differential, serum electrolytes, glucose, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, liver function tests, and lipid profile). The initial dose of aripiprazole was 2 to 5 mg daily, with further dose titrations based on tolerability and clinical response, up to a maximum of 30 mg daily. Efficacy and adverse effects were assessed and recorded at each follow-up appointment (bi-weekly for the first month and then monthly). Antidepressants, anxiolytics, and mood stabilizers were allowed but had to be kept at a constant dose during the 12- weeks treatment phase. As we were specifically interested in examining the benefits of aripiprazole augmentation in veterans with military-related PTSD, patients not prescribed aripiprazole augmentation were excluded from this chart review. For patients who were already prescribed an antipsychotic, the antipsychotic was discontinued prior to the initiation of aripiprazole.

The sample was derived from a retrospective chart review with approval from the Office of Research Ethics of the University of Western Ontario. Consent from each patient was not obtained specifically for this chart review. However, as part of the initial orientation to the clinic, all patients are asked to provide written consent to participate in research. All patients met the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD and comorbid major depressive disorder. To maximize the generalizability of this evaluation to usual "clinical practice," all comorbid physical and psychiatric conditions were included in the chart review.

Instruments

To diagnose PTSD, the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) [43] was administered by a trained clinician and the diagnosis of major depressive disorder was determined using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)[44] and the psychiatric interview according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria [6]. To assess change in PTSD symptoms with treatment, the PCL-M [40] was used. Similarly, the BDI [45,46] was used to assess change in depressive symptoms as a result of treatment. The SF-36 [47] was used to assess health related quality of life (HRQol). The SF-36 measures functional impairment in eight domains or subscales; the mental health sub scales can be collapsed into the Mental Component Summary (MCS) Score reflecting overall mental health [48]. The PCL-M, the BDI, and the SF-36 were all administered at each follow-up appointment including at intake (t1) and at 1-, 2-, and 3-month follow-ups (t2, t3, and t4) over the course of treatment. The total PCL-M and the total BDI were the primary efficacy variables; the total PCL-M re-experiencing, avoidance/numbing, and hyperarousal subscale scores served as secondary efficacy variables.

Analysis

The LOCF data for each visit included the data recorded at that visit or carried forward from the last visit. For the primary outcome, the Wilcoxon signed rank test and effect sizes (Cohen's d) was used to determine the statistical significance of the change from baseline total PCL-M and Total BDI score at each follow-up time point (t2, t3, t4). For the three secondary outcome measures (the PCL-M reexperiencing, avoidance/numbing, and hyperarousal subscale scores), only the effects at t4 were examined. To correct for multiple comparisons, we used Hochberg step-up multiple comparisons procedure [49].

For each of the two main outcomes, we identified responders on our two outcome measures using criteria established in existing literature. More specifically, on the PCL, we identified those with at least a 20% reduction in their total PCL scores as responders; [33] this is in keeping with prior treatment efficacy and more specifically, prior Aripiprazole treatment efficacy studies for PTSD [33]. On the BDI, we identified those with at least a 50% reduction in their symptom scores as responders [50].

Results

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Of the 27 participants, almost all were men (n = 26, 96.3%), with an average age of 39.36 years (SD = 5.98) and an average of 10.26 years (SD = 7.38) with PTSD symptoms. At intake, the majority (n = 20, 74.1%) of the sample had been released from the military. Years of military service averaged 15.04 years (SD = 7.41). Almost all (n = 26, 96.3%) had exposure to combat or to a war zone during their deployment and the most common deployments reported were Afghanistan (n = 9, 33.3%), the former Yugoslavia (n = 8, 29.6%), and Africa (Somalia, Rwanda, Eatrea, and Sierra Leone) (n = 5, 18.5%). All patients were taking an antidepressant prior to initiating aripiprazole, most commonly a norepinephrine dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) (n = 16, 59.3%), followed by noradrenergic specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSA) (n = 12, 44.4%); serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) (n = 11, 41.7%), and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (n = 10, 37%). Most patients (n = 14, 51.9%) were taking two antidepressant and an additional 14.8% (n = 4) were taking three antidepressant. In addition to an antidepressant, 8 patients (30.77%) were prescribed an anticonvulsant, 5 patients (19.23%) were prescribed a stimulant, and 4 patients (15.38%) were prescribed a hypnotic.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the sample

| Demographic and clinical variables | n (%) or mean (sd) |

|---|---|

| Age | 39.36 (6.09) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 26 (96.30%) |

| Female | 1 (3.70%) |

| Canadian Forces (CF) status | |

| Released | 20 (74.07%) |

| Still serving | 7 (25.93%) |

| Current Work Status | |

| Unemployed | 17 (62.96%) |

| Working for Pay | 6 (22.22%) |

| On Sick Leave from Work | 4 (14.81%) |

| Duration of illness | 10.26 (7.38) |

| SF-36 Mental component score | 20.22 (10.11) |

| SF-36 Physical component score | 32.48 (15.06) |

Twenty-seven patients had at least one post-baseline efficacy evaluation thus were included in the efficacy analysis. At intake, all participants met full criteria for PTSD based on the CAPS interview. The average duration of PTSD symptoms was 10.26 years (SD = 7.38), suggesting a chronic course for this sample. Intake scores on the PCL-M and the BDI averaged 56.11(SD = 12.66) and 30.44 years (SD = 7.86), respectively. On the PCL-M, a score of 50 is the conventional cut-off score for a positive screen for PTSD in veteran populations; [51] on the BDI, scores above 29 are considered indicative of severe depression [52]. SF-36 MCS and PCS were 20.22 (SD = 10.11) and 32.48 (SD = 15.06), respectively, indicating significant impairment in scales measuring both mental and physical functioning.

Dose and Tolerability

The final average dose of aripiprazole was 12.40 (SD = 4.35) mg daily. The mean value of weight decrease from baseline (mean = 99.25 kg, SD = 13.35) to the final visit is 1.05 kg (SD = 4.95). Only two patients discontinued the aripiprazole; one patient due to non-response and one due to intolerable restlessness. The remaining 25 patients tolerated the aripiprazole. The most common side effects reported were insomnia (N = 5/27, 18.5%); agitation/irritability (N = 4/27, 14.8%); restlessness (N = 3/27, 11.1%); and fatigue (N = 2/27, 7.4%). The good tolerability was likely related to lower starting doses (2 mg daily) and slow titration (increasing the dose by 2-5 mg every two weeks).

Treatment Efficacy

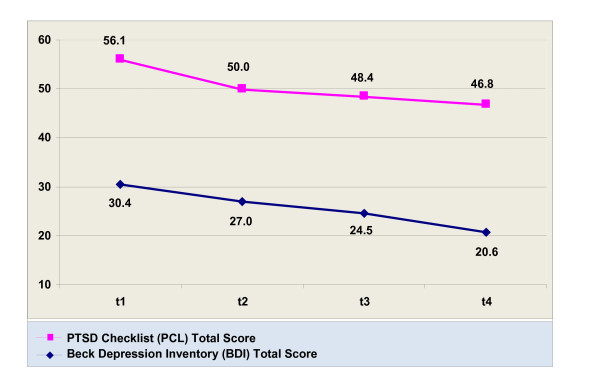

Results from Wilcoxon signed rank tests showed significant decreases between baseline and each of the three follow-ups for the BDI and the PCL, as well as the last visit for the PCL Reexperiencing, Avoidance, and Hyperarousal subscales (Table 2), even after multiple testing correction. The total PCL score decreased from 56.11 (SD = 12.66) at baseline to 46.85 (SD = 13.53) at three months and the total BDI score 30.44 (SD = 7.85) at baseline to 20.67 (SD = 10.05) at three months, figure 1. Effect sizes and changes in the clinical outcome variables from intake to the final visit are reported in Table 3.

Table 2.

Wilcoxon signed rank test between intake and each of the follow-ups

| Outcomes | p-value |

|---|---|

| BDI | |

| Difference between baseline and t2 | 0.0179 |

| Difference between baseline and t3 | 0.0042 |

| Difference between baseline and t4 | <0.0001 |

| PCL | |

| Difference between baseline and t2 | 0.0061 |

| Difference between baseline and t3 | 0.0016 |

| Difference between baseline and t4 | <0.0001 |

| Reexperiencing subscale | |

| Difference between baseline and t4 | 0.0020 |

| Avoidance subscale | |

| Difference between baseline and t4 | 0.0123 |

| Hyperarousal subscale | |

| Difference between baseline and t4 | 0.0043 |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory

PCL: PTSD Checklist

Figure 1.

Change in PCL and BDI total score from baseline (t1) to 3 months (t4) for patients receiving aripiprazole.

Table 3.

Effect sizes and changes in clinical outcome from baseline to final visit (N = 27)

| Intake (t1) | 3-month follow-up (t4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (range) | Mean (SD) | Median (range) | Effect size | |

| BDI Total | 30.44 (7.85) | 29 (14 - 44) | 20.67 (10.05) | 19 (3-43) | 1.09 |

| PCL Total | 56.11 (12.66) | 55 (34-87) | 46.85 (13.53) | 46 (23-67) | 0.90 |

| PCL Reexperiencing | 15.00 (4.42) | 15 (7-25) | 12.61 (4.72) | 12 (5-22) | 0.57 |

| PCL Avoidance | 23.40 (5.22) | 23 (14-34) | 21.05 (6.02) | 21 (10-31) | 0.38 |

| PCL Hyperarousal | 16.04 (4.02) | 16 (10-22) | 13.96 (4.32) | 14 (5-21) | 0.48 |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory

PCL: PTSD Checklist

Cohen's d was calculated for effect size

The number and percentage of responders at each of the follow-ups are reported in Table 4. Thirty seven percent (10/27) were considered responders, as defined by a decrease in total PCL scores of at least 20 percent and for depression, 19% (5/27) were considered responders as defined by a decrease in total BDI score of at least 50%. Overall, a higher percentage of participants met criteria for being a responder on the PCL than the BDI.

Table 4.

Frequency of responders at each of the follow-ups

| Measure | Responders (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-month (t2) (n = 27) | 2-months (t3) (n = 27) | 3-month (t4) (n = 27) | |

| PCL | 7(25.93%) | 9(33.33%) | 10(37.04%) |

| BDI | 1(3.70%) | 4(14.81%) | 5(18.52%) |

Responders on the PCL were those with 20% or greater improvement

Responders on the BDI were those with 50% or greater improvement

Additional analyses to examine the efficacy of aripiprazole among those with severe depression (BDI > 29) at intake (n = 14) found significant reductions in PCL symptom scores for this subsample as well, with the PCL scores averaging 61.79 (SD = 9.60), 51.86 (SD = 13.54), 52.14 (SD = 15.53), and 48.71 (SD = 13.02) at intake and each of the follow-ups, respectively. The Wilcoxon signed rank test results showed significant reductions from intake to each of the follow-ups (p = 0.0051, p = 0.0405, and 0.0010 for each of the follow-ups). The percentages of responders on PCL at each of the follow-ups are 35.71%, 42.86%, and 57.14%, respectively. It is worth noting that at t4, having severe depression was found to be associated with higher percentage of responders on PCL (P = 0.0461 from Fisher's exact test).

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies in veterans, [32-34] the addition of aripiprazole contributed to a reduction in PTSD symptomatology in all symptom clusters (reexperiencing, avoidance/numbing, and hyperarousal) and among those with severe comorbid major depression disorder (baseline BDI ≥ 29). A significant number (37%) demonstrated a significant reduction in PTSD symptomatology (decrease in total PCL scores of at least 20%). Also consistent with studies on treatment resistant depression, [53,54] the addition of aripiprazole demonstrated an overall reduction in depression severity from a total BDI score of 30.44 at baseline to 20.67 at three months.

The low response rate of PTSD symptoms observed in this chart review, when compared to the augmentation trial by Roberts and colleagues [33], might be related to higher rates of comorbid depression (100%) in this patient group. Furthermore, unlike the study by Berman [55] where 42% met the criteria for significant decrease in depression severity, in our chart review only a minority (19%) showed decrease in total BDI scores of at least 50%. The low response rate observed in our chart review compared to Berman and colleagues' [55] study might be related to the fact that in Berman's study, patients with comorbid PTSD were excluded. Also in this chart review, most patients (52.9%) reported depression in the severe range and most patients (n = 18, 66.7%) in this sample continue to be symptomatic despite being prescribed combination antidepressant prior to initiating aripiprazole, suggesting significant treatment resistance. Although modest, the response rate is particularly encouraging in a population of chronic military-related PTSD with comorbid major depression in the severe range, which has traditionally demonstrated poor response to pharmacotherapy. Clinically, it stresses the importance of encouraging patients to persist with treatment and to consider augmentation strategies for patients who demonstrate a partial response (25-50% improvement) or no response with optimization of monotherapy.

Due to significant limitations of this chart review, including a small sample size, the retrospective nature of the design, and a lack of a control group, careful interpretation of the findings is warranted. This was a preliminary, open-label retrospective chart review, with a small sample size. However, since most patients in this chart review had PTSD for more than 10 years, with comorbid major depression in the severe range, the observation that the majority of patients had improved scores for both PTSD and depression severity is noteworthy.

Conclusions

Military-related PTSD often presents with comorbid major depression requiring prompt and effective treatment. This chart review demonstrates that the addition of aripiprazole can assist in providing symptom relief in a population that has traditionally demonstrated poor pharmacological response. Further studies including double-blind, placebo-controlled studies are necessary to confirm our findings and further demonstrate the benefit of aripiprazole augmentation in the treatment of military- related PTSD.

Competing interests

Drs. Richardson, Fikretoglu and Liu have no disclosures to announce in association with the contents of this issue. Dr. McIntosh has acted as a presenter for, participated on an Advisory Board for, and/or received research funding from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Biovail, Bristol Myers-Squibb, Lundbeck, Forest, Servier, Sanofi-Aventis, Shire, and Janssen-Ortho.

Authors' contributions

DR conceptualized and designed the chart review and drafted the manuscript. DF contributed to the statistical analysis and AL completed the statistical analyses. DR, DF, AL and DM contributed to the interpretation of the results. All the authors contributed to the preparation of the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

J Don Richardson, Email: Don.Richardson@sjhc.london.on.ca.

Deniz Fikretoglu, Email: DENIZ.FIKRETOGLU@forces.gc.ca.

Aihua Liu, Email: liuaihua2002@yahoo.com.

Diane McIntosh, Email: drdianemcintosh@gmail.com.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Veterans Affairs Canada.

References

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan: Mental health problems and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT. The Psychological Demands of Peacekeeping. PTSD Clinical Quarterly. 1996;6(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, King LA, King DW, Orsillo SM, Friedman M. Warriors as Peacekeepers: Features of the Somalia Experience and PTSD. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(6):1001–1010. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Orsillo SM, Friedman M, Erhlich P, Batres A. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Associated with Peacekeeping Duty in Somalia for U.S. Military Personnel. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(5):178–184. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients with Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004. [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th-Text Revision edn. Washington, DC: Author. 2001.

- Iversen A, van Staden L, Hughes J, Browne T, Hull L, Hall J, Greenberg N, Rona R, Hotopf M, Wessely S. et al. The prevalence of common mental disorders and PTSD in the UK military: using data from a clinical interview-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9(1):68. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JD, Elhai J, Pedlar D. Association of PTSD and Depression with Medical and Specialist Care Utilization in Modern Peacekeeping Veterans in CanadaWith Health-Related Disabilities. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1240–1245. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M, Forbes D, Biddle D, Elliott P. Inpatient versus day hospital treatment for chronic, combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: A naturalistic comparison. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:183–189. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200203000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JD, Long ME, Pedlar D, Elhai JD. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Health Related Quality Of Life (HRQol) among a Sample of Treatment- and Pension-Seeking deployed Canadian Forces Peacekeeping Veterans. Can J Psychiatry. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Friedman M. Drug treatment for PTSD: answers and questions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997. pp. 359–371. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shalev A, Bonne, Eth S. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A review. Psychosom Med. 1996. pp. 165–182. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Creamer M, Morris P, Biddle D, Elliott P. Treatment outcome in Australian veterans with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: A cause for cautious optimism? J Trauma Stress. 1999;12:545–558. doi: 10.1023/A:1024702931164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DR, Rosenheck R, Fontana A, Lubin H, Charney D, Southwick S. Outcome of intensive inpatient treatment for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:771–777. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld FB, Marmar CR, Neylan TC. Current Concepts in Pharmacotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(5):519–531. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Creamer M, Hawthorne G, Allen N, McHugh T. Comorbidity as a predictor of symptom change after treatment in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191:93–99. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000051903.60517.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Wolfe J. Comorbidity in post-traumatic stress disorder: An analysis of community and clinical studies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1990;20:1776–1788. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1990.tb01511.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick S, Yehuda R, Giller EJ. Characterization of depression in war-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:179–183. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamner MB, Frueh C, Ulmer HG, Arana GW. Psychotic features and illness severity in combat veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:846–852. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David D, Kutcher G, Jackson E. Psychotic symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;60:29–32. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): The management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. London, vol. NICE Clinical Guideline No. 26.: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. 2005.

- Van der Kolk B, Dreyfuss D, Micheals M, Shera D, Berkowitz R, Fisler R, Saxe G. Fluoxetine in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:517–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzsberg M, Feldman M, Beckman J, Kudler H, Davidson J. Lack of efficacy for fluoxetine in PTSD: A placebo- controlled trial in combat veterans. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2000;12:101–105. doi: 10.1023/a:1009076231175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Psychiatric Association. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. In Clinical Practice Guiselines Management of Anxiety Disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(Suppl 2):57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Kline NA, Matloff JL. Adjunctive Olanzapine for SSRI-Resistant Combat-Related PTSD: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1777–1779. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamner MB, Faldowski RA, Ulmer HG, Frueh BC, Huber MG, Arana GW. Adjunctive risperidone treatment in post-traumatic stress disorder: a preliminary controlled trial of effects on comorbid psychotic symptoms. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:1–8. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200301000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnelly EP, Ciraulo DA, Knapp CTK. Low-dose risperidone as adjunctive therapy for irritable aggression in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:193–196. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200304000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartzokis G, Freeman T, Roca V. 154th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. New Orleans, LA; 2001. Risperidone for patients with chronic combat related posttraumatic stress disorder. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SH, Lam RW, Parikh SV, Patten SB, Ravindran AV. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(Suppl 1):S1–S2. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal G, Calais L, Cañive J, Lundy S, Pickard J, Toney G. Prospective study to evaluate the efficacy of aripiprazole as a monotherapy in patients with severe chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: an open trial. Pchopharmacology Bulletin. 2007;40:6–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert S, Hamner MB, Durkalski VL, Brown MW, Ulmer HG. An Open-Label Assessment of Aripiprazole in the Treatment of PTSD. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2009;42(1):69–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MT. Aripiprazole in the management of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in returning Global War on Terrorism veterans. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(3):185–187. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000185021.48279.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGavin J, Goa K. Aripiprazole. CNS Drugs. 2002;16:779–786. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200216110-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder S, McQuade R, Stock E, Kaplita S, Marcus R, Safferman A, Saha A, Ali M, Iwamoto T. Aripiprazole in the treatment of schizophrenia:safety and tolerability in short-term, placebo-controlled trials. Schizophr Res. 2003;61:123–136. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swainston H, Perry C. Aripiprazole:a review of its use in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Drugs. 2004;64:1715–1736. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas G, Shelton R, Smith J, Fava M. Augmentation of antidepressants with atypical antipsychotics for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:826–831. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v68n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical Antipsychotic Augmentation in Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Placebo-Controlled Randomized Trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980–991. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies: October 1993; San Antonio, Texas. International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; 1993. The PTSD checklist: Reliability, validity, & diagnostic utility. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinsk MBG. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and lnterpretation Guide. Boston: New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Klauminser G, Charney DS, Keane TM. A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: The CAPS-1. Behavior Therapist. 1990;18:187–188. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. The diagnosis and management of depression. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated; 1993. p. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Kosinski M, Bayliss M, McHorney C, Rogers W, Raczek A. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: Summary results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1995;33:AS264–AS279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. doi: 10.1093/biomet/75.4.800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RJ, Gott BM, Sayuk GS, Freedland KE, Lustman PJ. Antidepressant Pharmacotherapy in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):485–489. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SD, Calhoun PS. The diagnostic accuracy of the PTSD Checklist: A critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(8):976–987. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, Texas: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus RN, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Hennicken D, Fava M, Simon JS, Trivedi MH, Thase ME, Berman RM. The Efficacy and Safety of Aripiprazole as Adjunctive Therapy in Major Depressive Disorder: A Second Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(2):156–165. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31816774f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman RM, Fava M, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, Swanink R, Mcquade RD, Carson WH, Adson D, Taylor L, Hazel J. et al. Aripiprazole Augmentation in Major Depressive Disorder: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study in Patients with Inadequate Response to Antidepressants. CNS spectrums. 2009;14(4):197–206. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900020216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman RM, Marcus RN, Swanink R, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Corey-Lisle PKRN, Khan A. The Efficacy and Safety of Aripiprazole as Adjunctive Therapy in Major Depressive Disorder: A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:843–853. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v68n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]