Abstract

We examined to what extent increased parent reports of autistic traits in some children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are the result of ADHD-related symptoms or qualitatively similar to the core characteristics of autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Results confirm the presence of a subgroup of children with ADHD and elevated ratings of core ASD traits (ADHD+) not accounted for by ADHD or behavioral symptoms. Further, analyses revealed greater oppositional behaviors, but not ADHD severity or anxiety, in the ADHD+ subgroup compared to those with ADHD only. These results highlight the importance of specifically examining autistic traits in children with ADHD for better characterization in studies of the underlying physiopathology and treatment.

Keywords: Autism, Autism Spectrum Disorders, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Social Reciprocity, Social Responsiveness Scale, Children's Communication Checklist-2

Clinical anecdotes, case reports, and empirical studies demonstrate that many children display both ADHD and ASD symptoms (Hattori et al., 2006; Holtmann, Bolte, & Poustka, 2007; Mulligan et al., 2009; Nijmeijer et al., 2008; Reiersen & Todd, 2008; Nijmeijer et al., 2009; Rommelse et al., 2009; Rommelse, Franke, Geurts, Hartman, & Buitelaar, 2010). Yet, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), does not allow for the comorbid diagnoses of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Pervasive Developmental Disorders (referred to from here on as autism spectrum disorders, ASD). The prevalence of ADHD symptoms in individuals with a primary clinical diagnosis of ASD ranges between 13% and 50% in population and community based studies (Bradley & Isaacs, 2006; Icasiano, Hewson, Machet, Cooper, & Marshall, 2004; Keen & Ward, 2004; Montes & Halterman, 2006; Ronald, Simonoff, Kuntsi, Asherson, & Plomin, 2008; Simonoff et al., 2008) and between 20% and 85% in clinical samples (de Bruin, Ferdinand, Meester, de Nijs, & Verheij, 2007; Gadow, DeVincent, & Pomeroy, 2006; Gillberg, 1989; Goldstein & Schwebach, 2004; Holtmann, Bolte, & Poustka, 2005; Holtmann et al., 2007; Ogino et al., 2005; Lee & Ousley, 2006; Sinzig, Morsch, Bruning, Schmidt, & Lehmkuhl, 2008; Sturm, Fernell, & Gillberg, 2004; Wozniak et al., 1997). The presence and nature of ASD-like symptoms (i.e., autistic traits) in individuals with a primary diagnosis of ADHD has been increasingly noted (Hattori et al., 2006; Nijmeijer et al., 2008; Nijmeijer et al., 2009; Reiersen, Constantino, Volk, & Todd, 2007; Reiersen et al., 2008; Luteijn et al., 2000; Rommelse et al., 2009; Mulligan et al., 2009). However, this remains an understudied area.

Social difficulties are often reported in children with ADHD but these difficulties are typically interpreted as resulting from ADHD symptoms rather than reflecting the qualitative impairments in social-communicative functioning characteristic of ASD (Biederman et al., 1999; Greene et al., 1996; Hoza et al., 2005; Matthys, Cuperus, & van Engeland, 1999; Bagwell, Molina, Pelham, Jr., & Hoza, 2001; McQuade & Hoza, 2008). For example, several authors suggest that because of their impulsivity, children with ADHD are more likely to be rated as inappropriately intrusive during conversations or play (Abikoff et al., 2002), and are more likely to be rejected by their peers (Hoza et al., 2005; Greene et al., 1996). Using the Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents (SAICA; Orvaschel & Walsh, 1984), Greene et al. (1996) identified a group of children with ADHD as “socially disabled.” These children showed greater impairments in items assessing their ability to “get along with siblings,” “make friends easily,” or “be affectionate” across different contexts (home, school, and free-time). However, social difficulties often remain even after treating ADHD symptoms (see McQuade et al., 2008).

More recently, authors have examined the presence of social and communicative profiles qualitatively similar to those associated with ASD in individuals with ADHD (Nijmeijer et al., 2009; Reiersen et al., 2007; Carpenter, Loo, Yang, Dang, & Smalley, 2009; Geurts et al., 2004; Mulligan et al., 2009; Clark, Feehan, Tinline, & Vostanis, 1999). These studies have used a variety of parent-based instruments to measure deficits in social functioning. With one exception (Mulligan et al., 2009), authors have selected instruments that encompass a broad range of symptoms to capture milder forms on the autism spectrum. For example, Reiersen et al. (2007) identified a subgroup of ADHD children with autistic traits using parent ratings on the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS; Constantino, Przybeck, Friesen, & Todd, 2000; Constantino & Todd, 2000; Constantino & Todd, 2003; Constantino et al., 2003; Constantino et al., 2004), a continuously distributed, single-factor measure of social reciprocity skills associated with ASD (Constantino et al., 2004). Other authors have used the Children's Communication Checklist (CCC) and its revision, the CCC-2 (Geurts & Embrechts, 2008; Bishop & Baird, 2001; Geurts et al., 2004), to measure pragmatic aspects of language and found that children with ADHD are impaired in a similar manner as many children with ASD. Both the SRS and the CCC-2 are broad screening questionnaires that are designed to measure social-communicative impairment which is considered a core characteristic of ASD. They have been shown to discriminate ASD with high sensitivity but only moderate specificity, particularly in the presence of behavioral problems such as ADHD (Charman et al., 2007). Thus, it remains unclear whether elevated SRS or CCC-2 scores in some children with ADHD reflect underlying ASD symptoms or non-specifically increased behavioral difficulties.

The overarching aim of this study was to confirm the presence of elevated ratings of autistic traits in children with ADHD, and to characterize the children who exhibit elevated scores with respect to the severity of autistic traits, ADHD symptoms, and other measures of psychopathology. To accomplish this goal, we examined whether significantly elevated total SRS scores of children with ADHD were due to the severity of items tightly related to autistic traits or to those probing broader behavioral symptoms related to ADHD. Then, we contrasted the ADHD subgroup with elevated SRS ratings (ADHD+) to the remaining children with only ADHD (ADHD-) with respect to the CCC-2 (Bishop, 1998; Bishop, 2003) as a separate measure of autistic traits, as well as to other parent-based measures of psychopathology. Though the focus of this study was on children with ADHD with or without elevated SRS scores, a sample of typically developing children was included for illustrative purposes.

Methods

Sample recruitment

Data were collected from 75 children with DSM-IV-TR based ADHD (60 boys) between the ages of 7.1 and 17.8. Children with ADHD were recruited through referrals from the NYU Child Study Center Child & Family Associates, parent support groups, newsletters, flyers, and web/newspaper advertisements. We screened out prospective ADHD participants with a history of an ASD diagnosis.

Children with ADHD were included in the study if they presented elevated ratings (T score ≥60) on the Conners' Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long-Version (CPRS-R:L; Conners, Sitarenios, Parker, & Epstein, 1998; Conners, 1998) in at least one of the ADHD summary scales and if they were not referred for an explicit ASD diagnostic concern. Diagnosis was confirmed by administration of the Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for Children – Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1997) to the parent and child, separately, with 65 of the cases. To accommodate participants' schedules, the remaining 10 interviews were conducted with a parent/legal guardian only. Of the ADHD children, 38 (51%) were diagnosed with ADHD-Combined type (ADHD-C), 27 (36%) with ADHD-Predominantly Inattentive type (ADHD-I), six (8%) as Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive type (ADHD-HI), and four (5%) as ADHD Not Otherwise Specified (ADHD-NOS). Comorbid diagnoses were present, individually or in combination, in 26 children; they included Anxiety Disorders (two with Specific Phobia, two with Social Phobia, two with Generalized Anxiety Disorder, two with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, one with Panic Disorder, and three Anxiety Disorder NOS), Enuresis (n=5), Learning Disorders (n=2), Specific Language Disorder (n=2); Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD; n=7), one with Dysthymia, one with Tourette's Disorder, one with Tic Disorder, and one with Adjustment Disorder. Twenty-eight (37%) children were treated with psychoactive medication (25 with psychostimulants and one each with risperidone, atomoxetine, or paroxetine).

Sixty-nine typically developing children (TDC; 30 boys) were also included for comparison (see Appendix). TDC were recruited from the local community through flyers/advertisements, and word of mouth. Inclusion as a TDC required T-scores below 60 on all four CPRS-R:L ADHD-summary scales (Conners, 1997; Conners et al., 1998).

All children (TDC and ADHD) in this study were participating in ongoing studies at the NYU Child Study Center. All families received compensation of $60 for participating in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from parents and assent from children, as approved by the NYU School of Medicine institutional review board.

Primary Measure of Autistic Traits

Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS)

To identify autistic traits, we used the SRS parent version (Constantino et al., 2003). The SRS is composed of 65 items, 53 of which focus on social-communicative abilities. These items examine the ability to interpret social cues, to maintain social conversation, as well as to initiate social interaction. The 12 remaining items probe repetitive behaviors or restricted patterns of interest. The 65 SRS items have been found to form a single factor underlying ASD that is continuously distributed in the population (Constantino et al., 2003; Constantino et al., 2004).

A total T score on the SRS ≥60 (1 SD above the mean; Constantino & Gruber, 2005) was used as a cut-off to identify children with autistic traits (designated as ADHD+). Some SRS items were missing for six participants with ADHD and five with TDC (one, two, and three responses were missing for seven, three, and one child, respectively; the number of missing items did not differ between children with ADHD and TDC). To account for these missing items on the SRS we used a prorated raw total score for each participant in which the sum of the response scores was divided by the number of answered items and multiplied by 65, the total number of items. Using this prorated raw score, an adjusted total T score was obtained.

Consensus categories for SRS items - Classification based on symptom domains

We sought to identify the SRS items directly associated with the DSM-IV-TR criteria for ASD (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and to distinguish them from those describing behaviors present broadly in other psychiatric disorders, including ADHD. Specifically, each SRS item was classified by eight independent raters (co-authors CL, FXC, ADM, MM, RG, and three scorers from the University of Michigan Autism and Communication Disorders Center) into one of four categories. Three categories were based on the three DSM-IV autism domains: Reciprocal Social Interaction (S), Communication (C), or Restricted, Repetitive, and Stereotyped Patterns of Behavior/Interests (R). A fourth category (Non-SCR) identified items not exclusively related to the DSM-IV ASD diagnostic criteria. This allowed us to examine whether non-SCR items were over-represented in contributing to the elevated total T scores in ADHD+ rather than the ASD related categories (S, C, or R). Following the classification of the 65 SRS items into four categories, we computed the percentage of agreement among the eight raters for each item. Agreement between the eight raters ranged from 100% (for 19 items) to 38% (for two items). Specifically, 71% of the SRS items were coded with ≥75% agreement. For the five items on which no more than four raters agreed, RG and ADM reached a consensus on category assignment (see Appendix for item-by-item consensus and item domain classification in Table 3). As a result of this process, the S category contained 24 items, the C category contained eight items, and the R category contained 10 items. The remaining 23 items were coded as Non-SCR, i.e., not specifically associated with DSM-IV ASD criteria. For each participant, we computed mean summary scores S, C, R and non-SCR by calculating the sum of raw scores (0-3) of all items in the category and dividing it by the number of items within each category.

Other Clinical Measures Used to Characterize ADHD+

We used the Children's Communication Checklist-2 (CCC-2) as an additional measure of autistic traits to further characterize the ADHD+ subgroup in comparison to the ADHD-. The CCC-2 is a 70-item parent-based questionnaire that examines aspects of communicative functioning, including impairment in pragmatic aspects of language (Bishop, 1998; Bishop, 2003). Ten domains, each probed by seven items, are included: speech, syntax, semantics, coherence, inappropriate initiation, stereotyped language, use of context, non-verbal communication, social relations, and interests. The sum of scores on the first seven domains forms the General Communication Composite (GCC). A summary measure of social interests and pragmatic aspects of language, the Social Interaction Deviance Composite (SIDC), is computed by summing the score for the domains inappropriate initiation, nonverbal communication, social relation, and interests and subtracting the sum of the remaining domains (Bishop, 2003; Norbury, Nash, Baird, & Bishop, 2004). A GCC score below 55 in combination with a negative SIDC score, or a SIDC of -15 or below (regardless of the GCC score) suggests a communicative profile characteristic of ASD.

Finally, measures of psychopathology were obtained from parent ratings of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983) and the CPRS-R:L (Conners, 1997). The CBCL is a questionnaire used to measure symptoms often observed in children with varying psychiatric conditions, including externalizing problems such as aggressiveness, hyperactivity, and conduct problems, and internalizing problems, such as mood and anxiety symptoms. The CPRS-R:L assesses the behaviors associated with a diagnosis of ADHD in addition to a broad range of problematic behaviors, such as conduct, cognitive, anxiety, and social problems. Parents also provided demographic information and socio-economic status (SES) was estimated using the Hollingshead Index of Social Position (Hollingshead, 1975). The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI; Wechsler, 1999) provided estimates of IQ.

Statistical Analyses

To assess whether the ADHD+ and ADHD- subgroups differed with respect to any of the SRS consensus categories (S, C, R, and non-SCR), we modeled the four values as a function of subgroup, category, and their interaction, adjusting for age and sex. The S, C, R and non-SCR scores were modeled simultaneously using MANOVA type mixed effects models to account for the correlation between the four measures on the same individual (Song, 2007). To test whether the difference between ADHD+ and ADHD- was the same on all four categories we used a likelihood ratio test for the interaction between subgroups (a factor with 2 levels: ADHD+ and ADHD-) and category (a factor with 4 levels: S, C, R, and non-SCR); i.e., a chi-square test with 3 degrees of freedom. Significance was judged at level α=0.05, two-sided. To eliminate the potential confounding effect of psychopathology, analyses were also conducted adjusting for several covariates: CPRS-R:L DSM-IV-Inattentive, DSM-IV-HI, DSM-IV-Total, CBCL Internalizing behavior problems, CBCL Externalizing behavior problems, and CBCL Total problems. This analysis has 80% power of a two-sided test with α=0.05 to detect differences of magnitude of approximately (Cohen's d) d=0.50 using the mixed effects models without adjusting for covariates.

We compared ADHD+ and ADHD- with respect to categorical factors such as (i) ADHD subtype; (ii) medication (yes/no); (iii) comorbidity (yes/no), (iv) ethnicity, and (v) SES using chi-square tests for independence. Comparisons between ADHD+ and ADHD- for other continuous clinical characteristics (estimates of IQ, CCC-2, CBCL and CPRS-R:L) were based on univariate analyses using ANCOVA, covarying for age and sex. These last tests were two-sided, and, to correct for multiple comparisons on the numerous subscales, significance threshold was set at α=0.001. With our sample, we can detect effects of magnitude d=1.02 using models without covariate adjustment with 80% power. For both power estimates, adjusting for covariates, assuming covariates are associated with outcomes, increases power.

Results

Identification of the ADHD+ Subgroup

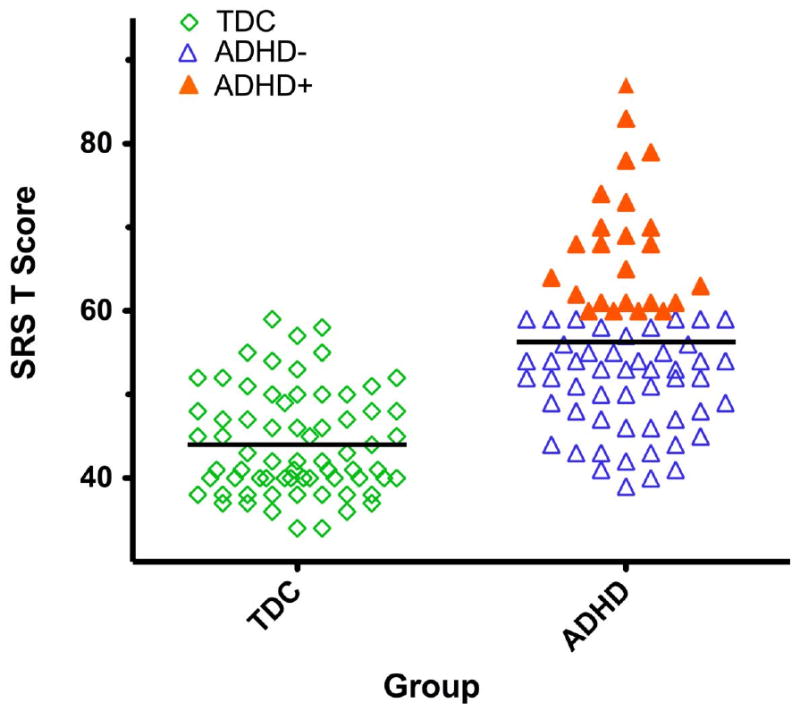

Based on the SRS Total adjusted T score ≥60, 24 (32%) of the children with ADHD were identified as ADHD+. The mean adjusted SRS T scores for ADHD+ was 67.7 ± 7.8 and for ADHD- 50.9 ± 5.8. As Figure 1 shows, the TDC and the ADHD groups as a whole presented with mean SRS Total adjusted T scores below 60 (44.0 ± 6.2 and 56.3 ± 10.2, respectively).

Figure 1.

The Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) Total T Score Distribution is displayed in the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) group (n=75) as a whole and, for illustration, in the typically developing children (TDC) (n=69; open diamonds). Both groups of children with ADHD and TDC had mean total SRS scores (displayed as black lines for each group) below the cut-off of 60 (1 SD above the population mean). However, 24 children with ADHD presented with total scores ≥ 60 and were classified as ADHD+ (filled orange triangles), the remaining 51 were classified as ADHD- (open blue triangles).

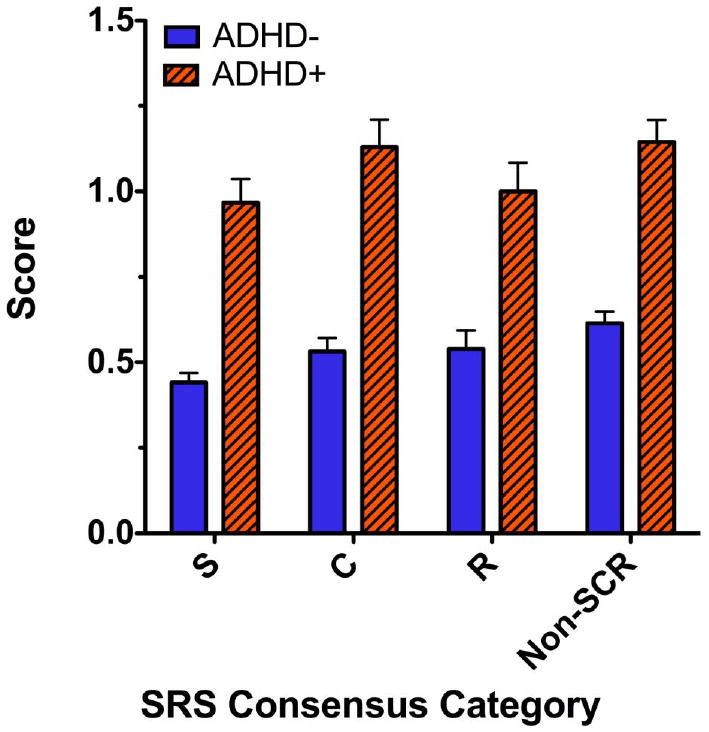

SRS Consensus Coding Differences in ADHD+ and ADHD-

The first question we addressed was whether the differences between ADHD+ and ADHD- were the same across all SRS categories (S, C, R, Non-SCR). The average category scores for both ADHD+ and ADHD- and their differences are reported in Table 2 and depicted in Figure 2. A likelihood ratio test showed that the difference between ADHD+ and ADHD- did not vary significantly across categories (χ2(3) = 2.23, p=0.53). Similar results were found after planned comparisons adjusting for ADHD severity (CPRS-R:L DSM-IV-Inattentive, DSM-IV-HI, and DSM-IV-Total) and for global CBCL measures of psychopathology (Internalizing Problems, Externalizing Problems, and Total Problems). Thus, the ADHD+ children had significantly elevated SRS scores (p<0.001) in each autism-like category as well as in the Non-SCR category, even after accounting for severity of psychopathology. See Table 1.

Table 2. TDC vs. ADHD- vs. ADHD+ Comparisons in Parent Ratings of Psychopathology.

|

TDC (n=69) |

ADHD- (n=51) |

ADHD+ (n=24) |

Group Comparisons | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square | ||||||||||

| x2 | df | p | ||||||||

| ADHD- Combined Type n (%) | - | 22 (43) | 16 (67) | 4.02 | 1 | <0.05 | ||||

| Males n (%) | 30 (43) | 41 (80) | 19 (79) | 20.5 | 2 | <0.001 | ||||

| Current Medication n (%) | - | 20 (39) | 8 (33) | 0.2 | 1 | 0.62 | ||||

| Comobidity Rate n (%) | - | 18 (35) | 8 (33) | 0.4 | 1 | 0.54 | ||||

| ANCOVA (age, sex) | ||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F | df | p | Post-Hoc | |

| Age | 12 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 11 | 3 | - | |||

| Full IQ | 112 | 13 | 110 | 14 | 107 | 14 | 1.0 | 2, 139 | 0.37 | - |

| Verbal IQ* | 114 | 14 | 110 | 14 | 108 | 17 | 1.6 | 2, 137 | 0.21 | - |

| Performance IQ* | 108 | 12 | 106 | 14 | 104 | 12 | 1.5 | 2, 137 | 0.24 | - |

| CPRS-R:L | ||||||||||

| Oppositional | 43 | 4 | 54 | 9 | 63 | 11 | 62.1 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| Cognitive/Inattentive | 46 | 4 | 68 | 9 | 70 | 6 | 238.1 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| Hyperactivity | 45 | 4 | 66 | 13 | 70 | 11 | 96.0 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| Anxious/Shy | 45 | 4 | 52 | 10 | 59 | 14 | 20.9 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Perfectionism | 45 | 5 | 49 | 7 | 53 | 9 | 9.1 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD+ |

| Social Problems | 46 | 2 | 53 | 10 | 61 | 14 | 28.3 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Psychosomatic | 46 | 6 | 54 | 13 | 56 | 15 | 12.7 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Restless-Impulsive | 45 | 4 | 66 | 9 | 70 | 8 | 191.6 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Emotional Lability | 44 | 4 | 51 | 9 | 57 | 15 | 24.4 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| ADHD Index | 44 | 3 | 70 | 8 | 71 | 6 | 380.5 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| GI Total | 44 | 3 | 63 | 8 | 68 | 8 | 175.4 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| DSM-IV Inattentive | 44 | 3 | 69 | 9 | 71 | 7 | 307.3 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| DSM-IV H-I | 45 | 4 | 66 | 13 | 73 | 10 | 114.0 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| DSM-IV Total | 44 | 3 | 70 | 8 | 74 | 5 | 186.4 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| CBCL | ||||||||||

| Anxious/Depressed | 51 | 2 | 58 | 7 | 60 | 9 | 23.1 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | 52 | 4 | 55 | 5 | 61 | 9 | 20.8 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC=ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| Somatic Complaints | 52 | 4 | 56 | 8 | 58 | 9 | 10.2 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Social Problems | 50 | 1 | 57 | 7 | 62 | 9 | 39.8 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Thought Problems | 51 | 3 | 58 | 8 | 64 | 8 | 40.4 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Attention Problems | 51 | 2 | 65 | 7 | 70 | 8 | 144.3 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Rule Breaking Behavior | 51 | 2 | 58 | 7 | 62 | 7 | 36.6 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Aggressive Behavior | 51 | 2 | 58 | 8 | 63 | 7 | 38.0 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Internalizing Prob | 44 | 8 | 55 | 11 | 61 | 9 | 30.9 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Externalizing Prob | 42 | 8 | 56 | 10 | 62 | 7 | 56.6 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Total Problems | 40 | 8 | 59 | 8 | 66 | 6 | 120.6 | 2, 139 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| CCC-2** | ||||||||||

| Speech | 10 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 3.9 | 2, 132 | 0.02 | - |

| Syntax | 10 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 11.9 | 2, 132 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD+ |

| Semantic | 11 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 12.4 | 2, 132 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

| Coherence | 11 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 25.0 | 2, 132 | <0.001 | TDC=ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| Inappropriate Initiation | 12 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 54.7 | 2, 132 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| Stereotyped | 11 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 27.5 | 2, 132 | <0.001 | TDC=ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| Context | 11 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 27.7 | 2, 132 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| Nonverbal | 11 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 45.6 | 2, 132 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| Social Problems | 11 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 42.0 | 2, 132 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| Interests | 11 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 21.5 | 2, 132 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| GCC | 88 | 18 | 72 | 16 | 49 | 15 | 37.5 | 2, 132 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-<ADHD+ |

| SIDC | 3 | 6 | -4.64 | 9 | -7.41 | 8 | 18.6 | 2, 132 | <0.001 | TDC<ADHD-=ADHD+ |

Note: GI=Global Index; H-I=Hyperactive/Impulsive

For 1 child classified as ADHD- (SRS T Score < 60) and 1 child classified as ADHD+ (SRS T score >60) estimates of PIQ and VIQ were unavailable.

As opposed to the other measures, lower scores on the CCC-2 indicate greater impairment; 2 ADHD- and 1 ADHD did not have usable CCC-2 (1 ADHD- and 1 ADHD+ had inconsistent parent scorings, 1 parent of a child classified as ADHD- had not completed the questionnaire). Additionally, 4 TDC did not have usable CCC-2 scores (2 had inconsistent parent scorings and 2 had not completed the questionnaire).

Figure 2.

The mean and standard errors of the scores corresponding to the four categories resulting from the item by item consensus classification of the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) are depicted for the ADHD+ (cross-hatched orange) and ADHD- (solid blue) subgroups. Three of these categories include items related to DSM-IV autism criteria: Social (S), Communication (C), Restricted/Repetitive Behavior/Interests (R), one category includes items not exclusively associated to autism (Non-SCR). As the graph shows, the ADHD+ group not only showed significantly greater increased scores in the non-SCR items but also on the three categories specifically related to autism (S, C, R).

Table 1. SRS Consensus Categories in ADHD+ and ADHD-.

|

ADHD- (n=51) |

ADHD+ (n=24) |

Linear Mixed Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Likelihood Ratio Test for effect of group | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | χ2 | df | p | |

| S | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.97 | 0.34 | 68.98 | 1 | <0.001 |

| C | 0.53 | 0.28 | 1.13 | 0.39 | |||

| R | 0.54 | 0.39 | 1.00 | 0.41 | |||

| Non-SCR | 0.61 | 0.24 | 1.14 | 0.32 | |||

Note: The Likelihood Ratio test for the interaction between group and category was χ2(3)=2.23, p=0.53.

Comparisons between ADHD+ and ADHD-

CCC-2

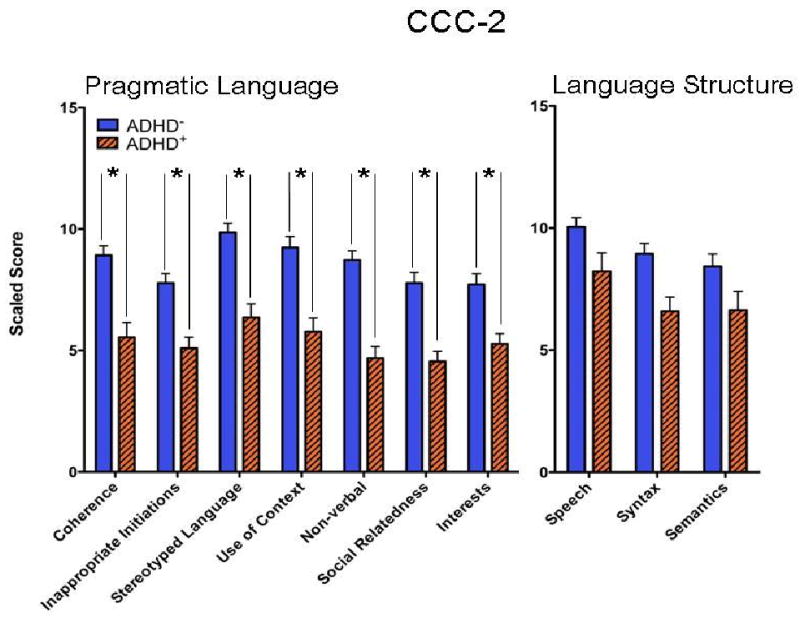

ADHD+ and ADHD- subgroups differed significantly in all CCC-2 domains except those domains that examine structural aspects of language: speech, syntax, and semantic domains. They also did not differ on the summary SIDC domain (see Table 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The mean and standard errors of the scaled scores corresponding to each sub-scale of the Children's Communication Checklist (CCC-2) are depicted for the ADHD+ (cross-hatched orange) and ADHD- (solid blue) subgroups. Three of these sub-scales (Speech, Syntax, and Semantics) are related to structural aspects of language (on the right side of the figure), while the remaining seven sub-scales are related to pragmatic aspects of language (on the left side of the figure). As the graph depicts, the ADHD+ group shows significantly lower (worse) scores on the sub-scales related to pragmatic language but not on the sub-scales related to language structure.

CBCL, CPRS-R:L

The ADHD+ subgroup had significantly higher ratings of oppositional behavior on the CPRS-R:L and greater scores on withdrawn/depressed and total problems scales on the CBCL. Mean CPRS-R:L and CBCL ratings of the other scales did not differ significantly between the ADHD+ and ADHD- subgroups.

ADHD subtypes, medication status, co-morbidity, and demographics

As shown in Table 2, compared to ADHD-, a higher proportion of the ADHD+ children were diagnosed as ADHD-C (43% vs. 67%, respectively), and a lower proportion was diagnosed as ADHD-I (43% vs. 21%, respectively). These proportions differed significantly as tested by a Fisher exact probability test (p<0.05). The ADHD+ and ADHD- subgroups did not differ significantly on ethnicity (χ2 (1, N = 73) = 1.30, p = 0.25), SES (χ2 (1, N = 71) = 0.63, p = 0.43), current use of medication, comorbidity rate, sex, age, or estimates of IQ.

Secondary Analyses

To examine the convergence between SRS and CCC-2 criteria in identifying children with ADHD and autistic traits (ADHD+), we determined the number of children with ADHD who met the CCC-2 criteria for a language profile consistent with ASD (i.e., GCC <55 and negative SIDC and/or SIDC < -15, Bishop, 2003). Thirty-five percent (n=25) of the 72 ADHD children with usable CCC-2 parent questionnaires met these criteria; 16 of these children overlapped with the ADHD+ per the SRS≥60 cutoff. Results of a chi-square test confirmed that the CCC-2 and SRS questionnaires were not independent, χ2 (1, N = 72) = 20.19, p < 0.001. Comparisons between the ADHD+ and ADHD- identified using the CCC-2 on the CPRS-R:L, and CBCL ratings yield similar results to the comparisons based on the SRS-identified subgroups (See Tables 5 and 6 in Appendix).

Discussion

In this study, a substantial proportion of the children with ADHD presented with elevated parent ratings of autistic traits (ADHD+). The proportion varied from about one-third, when using either the SRS or the CCC-2, to about one-fifth when both measures were combined to identify ADHD+. This confirmed previous findings of elevated ratings of autistic traits in ADHD (Reiersen et al., 2007; Reiersen et al., 2008; Santosh, Baird, Pityaratstian, Tavare, & Gringras, 2006; Mulligan et al., 2009). In addition we examined the extent to which such increased ratings may have reflected non-ASD symptoms using three different approaches. First, we categorized the SRS items into the three cardinal ASD diagnostic domains (Social, Communication, and Repetitive and Restrictive Behavior) and a category of items non-specifically related to ASD (non-SCR) and used their scores to compare ADHD+ to ADHD-. Previously, authors have suggested that social problems in children with ADHD are a result of the symptoms of this disorder (Greene et al., 1996; Charman et al., 2007; Marton, Wiener, Rogers, Moore, & Tannock, 2009). If the elevations on the SRS were solely a result of the behavioral impairments often observed in children with ADHD (e. g., impulsivity, inattention), we would expect greater elevations on the non-SCR category, than on the S, C, and/or R categories. The similarly elevated scores in all four categories (S, C, R, and non-SCR) observed in ADHD+ indicated that elevated parent rating of autistic traits (S, C, R) per the SRS did not exclusively reflect behavioral symptoms often observed in ADHD, as previously suggested (Greene et al., 1996; Charman et al., 2007; Marton et al., 2009). Second, we obtained similar results when controlling for severity of ADHD symptoms as well as other measures of psychopathology with the CBCL ratings (internalizing and externalizing problems), providing further evidence that elevated SRS ratings in ADHD+ do not simply reflect greater severity of internalizing, externalizing or ADHD symptoms. Third, we repeated the analyses on the SRS consensus categories comparing ADHD children with and without autistic traits per CCC-2 criteria instead of the SRS, and again found that autistic traits did not simply reflect behavioral impairments (as measured by the non-SCR items). Further, significant differences between ADHD+ and ADHD- on the CCC-2 pragmatic and social skills scales, but not on the language structure scales, provide additional evidence that the social reciprocity impairment in ADHD+ resembles the social reciprocity impairment seen in children with ASD. These observations suggest that a substantial number of children with ADHD present with social difficulties that may be qualitatively similar to autistic traits and which should be a focus of assessments and treatment planning.

ADHD+ children did not significantly differ from ADHD- with respect to inattention, hyperactivity or anxiety domains, nor did they differ on estimates of IQ. However, ratings of oppositional behaviors were significantly higher for ADHD+ children. This observation is consistent with the established association of increased social difficulties in children with ADHD and comorbid ODD (Greene et al., 1996; Mulligan et al., 2009; Matthys et al., 1999; Jensen et al., 1999). Similarly, ODD symptom severity has been found to be significantly higher in children with an ASD diagnosis and comorbid ADHD-like symptoms than in children with ASD symptoms alone (Gadow, DeVincent, & Drabick, 2008; Guttmann-Steinmetz, Gadow, & DeVincent, 2009). Less appreciated is the relationship between ODD and ASD traits in children with ADHD, which emerged from our data and from a recent large study of 821 children (Mulligan et al., 2009). In that study, elevated ratings on the Social Communication Questionnaire in ADHD were significantly related to increased prevalence of comorbid ODD and Conduct Disorder (Mulligan et al., 2009). Thus, the presence of elevated ASD traits in children with ADHD should stimulate both clinicians and investigators to further assess for comorbidities including ODD. In contrast to a recent result in an examination of ASD traits among siblings of children with ASD (Virkud, Todd, Abbacchi, Zhang, & Constantino, 2009), the presence of ASD traits in children with ADHD in our sample was not particularly categorical (i.e., did not depend on a specific cutoff). In fact, although we categorized ADHD subgroups with or without autistic traits based on a T-score cutoff of 60 on the SRS, the distribution of SRS scores was continuous. Further, we observed a similar pattern with more stringent cutoffs on the SRS of 65 or 70 (data not shown) and with the CCC-2 scores. The distribution of ASD symptoms in our sample supports the utility of considering ASD traits in ADHD from a dimensional perspective, which considers varying degrees of traits extending in the general population from healthy individuals to clinical groups (e.g., Constantino et al., 2004; Skuse et al., 2009; Di Martino et al., 2009). Examining autistic traits dimensionally in ADHD is more likely to inform our understanding of the underlying physiopathology, in part because of the greater statistical power afforded by dimensional analyses.

Results of this study support the growing literature examining the overlap of ASD and ADHD beyond clinical measures. Recent studies have found that the relation between autistic traits and ADHD symptoms is familial (Mulligan et al., 2009; Nijmeijer et al., 2009) and is mostly accounted for by genetic influences as shown by the greater similarity among monozygotic than dizygotic twins (Ronald et al., 2008). Similarly, a substantial proportion of the genetic influences on self-reported ADHD and autistic symptoms were found to be shared in a young adult twin sample (Reiersen, Constantino, Grimmer, Martin, & Todd, 2008). A clue to one possible source of such a common etiologic relationships was reported by Smalley et al. (2002) who found that ADHD and autism share a common and overlapping susceptible locus in chromosome 16p13. More recently, excessive frequency of large, rare copy number variations in chromosome 16p13 were reported in a well-characterized ADHD sample, thus further supporting the potential overlap between some forms of ADHD and autism (Williams et al., 2010). Beyond the overlap of core diagnostic symptoms of ADHD and ASD, several lines of evidence indicate that these two diagnostic entities share common deficits in other areas including motor coordination (Reiersen, Constantino, & Todd, 2008), attention control and executive functions (Corbett & Constantine, 2006; Reiersen et al., 2008; Fine, Semrud-Clikeman, Butcher, & Walkowiak, 2008; Schatz, Weimer, & Trauner, 2002; Geurts, Verte, Oosterlaan, Roeyers, & Sergeant, 2004), facial affect processing (Sinzig, Morsch, & Lehmkuhl, 2008; Yuill & Lyon, 2007), and theory of mind (Buitelaar, Van der Wees, Swaab-Barneveld, & van der Gaag, 1999; Sinzig et al., 2008). To date, only one MRI study has examined the neuronal overlap between ASD and ADHD. Brieber et al. (2007) found gray matter volume reductions in the parietal lobe and gray matter density reductions in the temporal lobe in both groups. Clearly, further examinations of the overlap between ASD and ADHD are warranted at the neuropsychological, physiological, and genetic domains.

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations

The principal limitation is that we relied exclusively on parent questionnaires as a measure of autistic traits. Further, we did not use gold-standard instruments, such as the ADOS, to rule out ASD. However, we excluded prospective participants with previous diagnoses of ASD, and children were evaluated by experienced clinicians using standardized assessments of psychopathology. In ongoing follow-up studies, we are specifically assessing autistic traits with multiple informants, including direct observations by clinicians blind to presumptive diagnosis. Additionally, our referral sample cannot be considered representative of ADHD; however, we highlight the consistency in the clinical presentation of children in our sample with children in other studies (i.e., Geurts et al., 2004; Reiersen et al., 2007).

In conclusion, the results of this study have implications for the assessment and treatment of autistic traits in children with ADHD both in regard to the recognition of their social difficulties and their increased risk of comorbid ODD. It is likely that the DSM-IV-TR exclusion of the diagnosis of ASD in individuals with ADHD may prevent appropriate identification and targeted treatment. Finally, the appreciation of a specific social impairment associated with ASD in some children with ADHD may provide a means to dissect the biological components underlying these disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by grants from NARSAD and NIMH (K23MH087770) awarded to Adriana Di Martino and to F. Xavier Castellanos by NICHD (R01HD065282), Autism Speaks, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, the Leon Levy Foundation, and the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation.

The authors wish to thank four anonymous clinicians at the University of Michigan Autism and Communication Disorders Center for graciously providing their SRS item classification, Dylan Gee, B.A., for helping in data collection, Sherine Khalil, M.P.A., for her dedicated work on research administration, and Amy Krain Roy, Ph.D., for helpful suggestions on an earlier version of this manuscript. Most of all the authors want to express their sincere gratitude to the parents and their children who have dedicated their time and commitment to this research.

Appendix

Table 3. SRS Item-by-item Consensus Coding.

| Item # | Social (S; 24 items) | % agreement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Incongruent facial expressions | 75 | |

| 6 | Solitary | 88 | |

| 7 | Awareness of others' state of mind | 63 | |

| 10 | Very literal | 75 | |

| 15* | Identifying others' facial expressions and verbal tone | 50 | |

| 16 | Poor eye gaze | 88 | |

| 18 | Trouble forming friendships | 100 | |

| 22 | Engages with other peers | 75 | |

| 23 | Avoids group activities | 100 | |

| 26 | Comforts those in distress | 88 | |

| 27 | Does not initiate social interchanges | 75 | |

| 33 | Socially awkward | 88 | |

| 34 | Avoids emotional intimacy with others | 100 | |

| 37** | Trouble relating to peers | 100 | |

| 38 | Modulates his/her response according to the mood of others | 100 | |

| 45 | Pays attention to what others are interested in | 100 | |

| 46 | Facial expressions are too serious | 88 | |

| 47 | Acts silly or laughs at unsuitable moments | 75 | |

| 54 | Reacts to people as objects | 100 | |

| 55 | Is aware of other's “personal space” | 75 | |

| 56 | Walks in between two people…. | 63 | |

| 60 | Does not display his/her feelings | 100 | |

| 63 | Inappropriately touches others | 75 | |

| 65 | Daydreams | 63 | |

| Communication (C; 8 items) | |||

| 12* | Tells others how he/she feels | 38 | |

| 13 | Poor turn-taking skills during conversations | 88 | |

| 19 | Frustrated in trying to verbally convey ideas | 63 | |

| 21 | Imitation of others' actions | 63 | |

| 35 | No typical flow in conversations | 100 | |

| 40 | Make-believe games | 100 | |

| 51 | Trouble responding to questions in a direct fashion | 75 | |

| 53 | Mechanical speech | 63 | |

| Restricted, Repetitive Behaviors or Interests (R; 10 items) | |||

| 4 | Unusual unyielding patterns of behavior when under stress | 100 | |

| 20 | Odd sensory interests | 100 | |

| 24 | Trouble with transitions or changes in schedule | 100 | |

| 28 | Repetitive thoughts…. | 63 | |

| 31 | Cannot stop thinking about a particular subject/topic | 88 | |

| 39 | Limited interests | 100 | |

| 42 | Particularly responsive to sensory input | 88 | |

| 50 | Hands mannerisms | 100 | |

| 58 | Details instead of the big picture | 88 | |

| 61 | Difficult time modifying his/her views | 100 | |

| Not Autism Specific (Non-SCR; 23 items) | |||

| 1 | More active in social situations | 75 | |

| 3 | Confident when engaging with others | 63 | |

| 5 | Socially naïve | 63 | |

| 8 | Strange bizarre behaviors | 63 | |

| 9 | Overly reliant on adults | 75 | |

| 11 | Confident | 100 | |

| 14 | Clumsy | 88 | |

| 17 | Knows when something is not just | 63 | |

| 25 | Unaware about being different from others | 63 | |

| 29* | His/her peers think he/she is strange | 38 | |

| 30 | Upset in situations with a lot happening | 63 | |

| 32 | Appropriate hygiene | 100 | |

| 36 | Trouble relating to adults | 63 | |

| 41 | Shifts from one task to another | 88 | |

| 43 | Does not display anxiety when parents are gone | 75 | |

| 44 | Poor concept of cause and effect | 75 | |

| 48* | Is humorous | 50 | |

| 49 | Does very well with some things but not with others | 75 | |

| 52* | Aware of being too loud | 50 | |

| 57 | Bullied/teased | 88 | |

| 59 | Suspicious | 88 | |

| 62 | Irrational motivations for doing things | 88 | |

| 64 | Anxious in social interactions | 75 | |

Note:

For items 12, 15, 29, 48, and 52, 4 or fewer coders agreed on any one category. Thus, authors RG and ADM came to a consensus on these items.

Item 37 was consensus coded by 7 clinicians instead of 8. Items from the SRS copyright © 2005 by Western Psychological Services. Item content adapted for scholarly reference purposes and reprinted by permission of the publisher, Western Psychological Services, 12031 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles, California, 90025, U.S.A. (rights@wpspublish.com) Not to be reprinted in whole or in part for any additional purpose without the expressed, written permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Table 4. ADHD- vs. ADHD+ Comparisons in Parent Ratings of Psychopathology (CCC-Based).

|

ADHD- (n=47) |

ADHD+ (n=25) |

Group Comparisons Chi-Square | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x2 | df | p | |||||

| Males n (%) | 40 (85) | 18 (72) | 1.8 | 1 | 0.18 | ||

| ANCOVA (age, sex) | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F | df | p | |

| Full IQ | 107.13 | 13.15 | 111.16 | 15.48 | 0.71 | 1, 68 | 0.40 |

| Verbal IQ* | 108.26 | 13.58 | 110.92 | 17.91 | 0.22 | 1, 67 | 0.64 |

| Performance IQ* | 104.32 | 13.52 | 107.46 | 13.40 | 0.60 | 1, 67 | 0.44 |

| CPRS-R:L | |||||||

| Oppositional | 54.13 | 9.12 | 61.68 | 11.28 | 8.85 | 1, 68 | 0.004 |

| Cognitive/Inattentive | 69.11 | 8.01 | 68.92 | 7.95 | 0.24 | 1, 68 | 0.62 |

| Hyperactivity | 65.04 | 12.77 | 71.36 | 10.19 | 4.16 | 1, 68 | 0.05 |

| Anxious/Shy | 53.15 | 11.37 | 56.24 | 11.49 | 1.75 | 1, 68 | 0.19 |

| Perfectionism | 48.32 | 7.96 | 53.36 | 8.29 | 6.60 | 1, 68 | 0.01 |

| Social Problems | 51.26 | 8.02 | 63.76 | 14.71 | 21.06 | 1, 68 | <0.001 |

| Psychosomatic | 52.00 | 11.62 | 60.48 | 16.08 | 5.96 | 1, 68 | 0.02 |

| Restless-Impulsive | 64.79 | 8.53 | 72.20 | 8.55 | 10.49 | 1, 68 | 0.002 |

| Emotional Lability | 50.79 | 10.86 | 56.60 | 12.01 | 3.44 | 1, 68 | 0.07 |

| ADHD Index | 69.43 | 6.92 | 71.76 | 7.78 | 0.80 | 1, 68 | 0.38 |

| GI Total | 61.74 | 8.31 | 69.00 | 8.00 | 10.98 | 1, 68 | 0.001 |

| DSM-IV Inattentive | 69.11 | 8.21 | 70.96 | 8.19 | 0.29 | 1, 68 | 0.59 |

| DSM-IV H-I | 65.83 | 12.62 | 73.00 | 10.11 | 5.48 | 1, 68 | 0.02 |

| DSM-IV Total | 69.57 | 7.81 | 73.68 | 6.54 | 3.82 | 1, 68 | 0.06 |

| CBCL | |||||||

| Anxious/Depressed | 56.74 | 7.19 | 61.52 | 8.18 | 6.68 | 1, 68 | 0.01 |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | 55.06 | 5.83 | 60.64 | 8.99 | 11.61 | 1, 68 | 0.001 |

| Somatic Complaints | 55.53 | 7.08 | 59.92 | 9.14 | 4.31 | 1, 68 | 0.04 |

| Social Problems | 55.19 | 6.11 | 64.40 | 7.43 | 32.62 | 1, 68 | <0.001 |

| Thought Problems | 58.00 | 7.57 | 64.72 | 7.56 | 13.74 | 1, 68 | <0.001 |

| Attention Problems | 64.91 | 7.28 | 70.40 | 7.19 | 8.00 | 1, 68 | 0.006 |

| Rule Breaking Behavior | 58.19 | 7.28 | 61.88 | 7.32 | 4.13 | 1, 68 | 0.05 |

| Aggressive Behavior | 57.19 | 7.81 | 63.08 | 7.53 | 8.97 | 1, 68 | 0.004 |

| Internalizing Prob | 53.43 | 10.70 | 62.40 | 7.43 | 13.38 | 1, 68 | <0.001 |

| Externalizing Prob | 55.57 | 10.20 | 62.84 | 7.70 | 9.62 | 1, 68 | 0.003 |

| Total Problems | 58.19 | 7.94 | 66.64 | 5.65 | 22.36 | 1, 68 | <0.001 |

| SRS | |||||||

| SRS T Total (adjusted for pro-rating**) | 51.89 | 7.26 | 64.28 | 10.18 | 34.93 | 1, 68 | <0.001 |

Note: GI=Global Index; H-I=Hyperactive/Impulsive

For 1 child classified as ADHD+ estimates of PIQ and VIQ were unavailable.

Six participants with ADHD and five TDC had at least one missing SRS question (one, two, and three responses were missing for seven, three, and one child, respectively; ADHD children and TDC did not differ in the number of missing questions). See text regarding pro-rated scores.

Table 5. SRS Consensus Categories in ADHD+ and ADHD- (CCC-based).

| ADHD- (n=47) |

ADHD+ (n=25) |

Linear Mixed Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Likelihood Ratio Test for effect of group | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | χ2 | df | p | |

| S | 0.46 | 0.23 | 0.86 | 0.38 | 23.19 | 1 | <0.001 |

| C | 0.59 | 0.31 | 0.97 | 0.51 | |||

| R | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.91 | 0.40 | |||

| Non-SCR | 0.67 | 0.29 | 1.01 | 0.39 | |||

Note: The Likelihood Ratio test for the interaction between group and category was χ2(3)=0.43, p=0.93.

Footnotes

At the time of this study Catherine Lord was an Adjunct Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the New York University Child Study Center, NY, NY, USA, while also holding her primary affiliation with the University of Michigan Autism and Communication Disorder Center that is currently her unique affiliation. Maria Angeles Mairena M.S. and Matthew O'Neale, previously at the NYU Child Study Center, are now affiliated with the Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain and New York University, College of Arts & Science, respectively.

Reference List

- Abikoff HB, Jensen PS, Arnold LL, Hoza B, Hechtman L, Pollack S, et al. Observed classroom behavior of children with ADHD: relationship to gender and comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:349–359. doi: 10.1023/a:1015713807297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, Molina BS, Pelham WE, Jr, Hoza B. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and problems in peer relations: predictions from childhood to adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1285–1292. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Mick E, Williamson S, Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, et al. Clinical correlates of ADHD in females: findings from a large group of girls ascertained from pediatric and psychiatric referral sources. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:966–975. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DV. Development of the Children's Communication Checklist (CCC): a method for assessing qualitative aspects of communicative impairment in children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1998;39:879–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DV. The Children's Communication Checklist- CCC-2 Manual 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DV, Baird G. Parent and teacher report of pragmatic aspects of communication: use of the children's communication checklist in a clinical setting. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2001;43:809–818. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201001475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EA, Isaacs BJ. Inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity in teenagers with intellectual disabilities, with and without autism. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry-Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 2006;51:598–606. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitelaar JK, Van der Wees M, Swaab-Barneveld H, van der Gaag RJ. Theory of mind and emotion-recognition functioning in autistic spectrum disorders and in psychiatric control and normal children. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:39–58. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter RE, Loo SK, Yang M, Dang J, Smalley SL. Social functioning difficulties in ADHD: association with PDD risk. Clinical Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2009;14:329–344. doi: 10.1177/1359104508100890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman T, Baird G, Simonoff E, Loucas T, Chandler S, Meldrum D, et al. Efficacy of three screening instruments in the identification of autistic-spectrum disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:554–559. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark T, Feehan C, Tinline C, Vostanis P. Autistic symptoms in children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;8:50–55. doi: 10.1007/s007870050083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Conners' Rating Scales-Revised User's Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Rating scales in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Use in assessment and treatment monitoring. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK, Sitarenios G, Parker JD, Epstein JN. The revised Conners' Parent Rating Scale (CPRS-R): factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:257–268. doi: 10.1023/a:1022602400621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Davis SA, Todd RD, Schindler MK, Gross MM, Brophy SL, et al. Validation of a brief quantitative measure of autistic traits: comparison of the social responsiveness scale with the autism diagnostic interview-revised. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33:427–433. doi: 10.1023/a:1025014929212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Gruber CP. Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS): Manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Gruber CP, Davis S, Hayes S, Passanante N, Przybeck T. The factor structure of autistic traits. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2004;45:719–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Przybeck T, Friesen D, Todd RD. Reciprocal social behavior in children with and without pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2000;21:2–11. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200002000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Todd RD. Genetic structure of reciprocal social behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:2043–2045. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Todd RD. Autistic traits in the general population: a twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:524–530. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Constantine LJ. Autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Assessing attention and response control with the Integrated Visual and Auditory Continuous Performance Test. Child Neuropsychology. 2006;12:335–348. doi: 10.1080/09297040500350938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin EI, Ferdinand RF, Meester S, de Nijs PF, Verheij F. High rates of psychiatric co-morbidity in PDD-NOS. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:877–886. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino A, Shehzad Z, Kelly C, Roy AK, Gee DG, Uddin LQ, et al. Relationship between cingulo-insular functional connectivity and autistic traits in neurotypical adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:891–899. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine JG, Semrud-Clikeman M, Butcher B, Walkowiak J. Brief report: Attention effect on a measure of social perception. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:1797–1802. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0570-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ, Drabick DA. Oppositional defiant disorder as a clinical phenotype in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:1302–1310. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0516-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ, Pomeroy J. ADHD symptom subtypes in children with pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36:271–283. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts HM, Embrechts M. Language Profiles in ASD, SLI, and ADHD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts HM, Verte S, Oosterlaan J, Roeyers H, Hartman CA, Mulder EJ, et al. Can the Children's Communication Checklist differentiate between children with autism, children with ADHD, and normal controls? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:1437–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts HM, Verte S, Oosterlaan J, Roeyers H, Sergeant JA. How specific are executive functioning deficits in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2004;45:836–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg C. Asperger Syndrome in 23 Swedish Children. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 1989;31:520–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1989.tb04031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S, Schwebach AJ. The comorbidity of Pervasive Developmental Disorder and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: results of a retrospective chart review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2004;34:329–339. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000029554.46570.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene RW, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Ouellette CA, Penn C, Griffin SM. Toward a new psychometric definition of social disability in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:571–578. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199605000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmann-Steinmetz S, Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ. Oppositional Defiant and Conduct Disorder Behaviors in Boys With Autism Spectrum Disorder With and Without Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Versus Several Comparison Samples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori J, Ogino T, Abiru K, Nakano K, Oka M, Ohtsuka Y. Are pervasive developmental disorders and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder distinct disorders? Brain & Development. 2006;28:371–374. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. New Haven: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Holtmann M, Bolte S, Poustka F. ADHD, Asperger syndrome, and high-functioning autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:1101. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000177322.57931.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmann M, Bolte S, Poustka F. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in pervasive developmental disorders: association with autistic behavior domains and coexisting psychopathology. Psychopathology. 2007;40:172–177. doi: 10.1159/000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Mrug S, Gerdes AC, Hinshaw SP, Bukowski WM, Gold JA, et al. What aspects of peer relationships are impaired in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:411–423. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icasiano F, Hewson P, Machet P, Cooper C, Marshall A. Childhood autism spectrum disorder in the Barwon region: A community based study. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2004;40:696–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Arnold LE, Richters JE, Severe JB, Vereen D, Vitiello B. Moderators and mediators of treatment response for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the Multimodal Treatment Study of children with Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:1088–1096. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen D, Ward S. Autistic spectrum disorder: a child population profile. Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice. 2004;8:39–48. doi: 10.1177/1362361304040637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DO, Ousley OY. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in a clinic sample of children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2006;16:737–746. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luteijn EF, Serra M, Jackson S, Steenhuis MP, Althaus M, Volkmar F, et al. How unspecified are disorders of children with a pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified? A study of social problems in children with PDD-NOS and ADHD. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;9:168–179. doi: 10.1007/s007870070040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marton I, Wiener J, Rogers M, Moore C, Tannock R. Empathy and social perspective taking in children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:107–118. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthys W, Cuperus JM, van Engeland H. Deficient social problem-solving in boys with ODD/CD, with ADHD, and with both disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:311–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuade JD, Hoza B. Peer problems in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: current status and future directions. Developmental Disabilities and Research Reviews. 2008;14:320–324. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes G, Halterman JS. Characteristics of school-age children with autism. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2006;27:379–385. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200610000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan A, Anney RJL, O'Regan M, Chen W, Butler L, Fitzgerald M, et al. Autism symptoms in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Familial trait which Correlates with Conduct, Oppositional Defiant, Language and Motor Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:197–209. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0621-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijmeijer JS, Hoekstra PJ, Minderaa RB, Buitelaar JK, Altink ME, Buschgens CJ, et al. PDD symptoms in ADHD, an independent familial trait? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:443–453. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijmeijer JS, Minderaa RB, Buitelaar JK, Mulligan A, Hartman CA, Hoekstra PJ. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and social dysfunctioning. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:692–708. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbury CF, Nash M, Baird G, Bishop D. Using a parental checklist to identify diagnostic groups in children with communication impairment: a validation of the Children's Communication Checklist--2. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2004;39:345–364. doi: 10.1080/13682820410001654883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogino T, Hattori J, Abiru K, Nakano K, Oka E, Ohtsuka Y. Symptoms related to ADHD observed in patients with pervasive developmental disorder. Brain & Development. 2005;27:345–348. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Walsh G. The Assessment of Adaptive Functioning in Children: A review of Existing Measures Suitable for Epidemiological and Clinical Services Research. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, NIMH, Division of Biometry and Epidemiology; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Reiersen AM, Constantino JN, Grimmer M, Martin NG, Todd RD. Evidence for shared genetic influences on self-reported ADHD and autistic symptoms in young adult Australian twins. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2008;11:579–585. doi: 10.1375/twin.11.6.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiersen AM, Constantino JN, Todd RD. Co-occurrence of motor problems and autistic symptoms in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:662–672. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816bff88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiersen AM, Constantino JN, Volk HE, Todd RD. Autistic traits in a population-based ADHD twin sample. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2007;48:464–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiersen AM, Todd RD. Co-occurrence of ADHD and autism spectrum disorders: phenomenology and treatment. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8:657–669. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommelse NN, Franke B, Geurts HM, Hartman CA, Buitelaar JK. Shared heritability of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;19:281–295. doi: 10.1007/s00787-010-0092-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommelse NNJ, Altink ME, Fliers EA, Martin NC, Buschgens CJM, Hartman CA, et al. Comorbid Problems in ADHD: Degree of Association, Shared Endophenotypes, and Formation of Distinct Subtypes. Implications for a Future DSM. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:793–804. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9312-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronald A, Simonoff E, Kuntsi J, Asherson P, Plomin R. Evidence for overlapping genetic influences on autistic and ADHD behaviours in a community twin sample. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2008;49:535–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santosh PJ, Baird G, Pityaratstian N, Tavare E, Gringras P. Impact of comorbid autism spectrum disorders on stimulant response in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a retrospective and prospective effectiveness study. Child Care Health and Development. 2006;32:575–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz AM, Weimer AK, Trauner DA. Brief report Attention differences in Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2002;32:333–336. doi: 10.1023/a:1016339104165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:921–929. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinzig J, Morsch D, Bruning N, Schmidt MH, Lehmkuhl G. Inhibition, flexibility, working memory and planning in autism spectrum disorders with and without comorbid ADHD-symptoms. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2008;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinzig J, Morsch D, Lehmkuhl G. Do hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention have an impact on the ability of facial affect recognition in children with autism and ADHD? European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;17:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skuse DH, Mandy W, Steer C, Miller LL, Goodman R, Lawrence K, et al. Social communication competence and functional adaptation in a general population of children: preliminary evidence for sex-by-verbal IQ differential risk. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:128–137. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819176b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley SL, Kustanovich V, Minassian SL, Stone JL, Ogdie MN, McGough JJ, et al. Genetic linkage of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on chromosome 16p13, in a region implicated in autism. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;71:959–963. doi: 10.1086/342732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song PSK. Correlated Data Analysis: Modeling, Analytics, and Applications. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm H, Fernell E, Gillberg C. Autism spectrum disorders in children with normal intellectual levels: associated impairments and subgroup. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2004;46:444–447. doi: 10.1017/s0012162204000738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virkud YV, Todd RD, Abbacchi AM, Zhang Y, Constantino JN. Familial aggregation of quantitative autistic traits in multiplex versus simplex autism. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2009;150B:328–334. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Williams NM, Zaharieva I, Martin A, Langley K, Mantripragada K, Fossdal R, et al. Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2010 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61109-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak J, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Frazier J, Kim J, Millstein R, et al. Mania in children with pervasive developmental disorder revisited. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1552–1559. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(09)66564-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuill N, Lyon J. Selective difficulty in recognising facial expressions of emotion in boys with ADHD. General performance impairments or specific problems in social cognition? European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;16:398–404. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0612-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]