Abstract

Development of in vitro models to study smooth muscle cell (SMC) differentiation has been hindered by some peculiarities intrinsic to these cells, namely their different embryological origins and their ability to undergo phenotypic modulation in cell culture. Although many in vitro models are available to study SMC differentiation, careful consideration should be taken so that the model chosen fits the questions being addressed. In this review we will summarize several well established in vitro models available to study SMC differentiation from stem cells and outline novel mechanisms recently identified underlying SMC differentiation programs.

Introduction

Alterations in vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) normal functions and phenotypic modulation play major roles in a number of diseases including atherosclerosis, restenosis, hypertension, and aneurysm 1. A better understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms that control VSMC differentiation is essential to help develop new approaches to both prevent and treat these diseases. Therefore, development of reliable and reproducible in vitro cellular models to study SMC differentiation is needed, yet it has been problematic due to intrinsic peculiarities of SMC.

VSMC originate from at least five different sources of progenitors during embryonic development, including neural crest, proepicardium, serosal mesothelium, secondary heart field and somites 2, 3. VSMC populations from different embryonic origins are observed in different vessels, as well as within segments of the same vessel, albeit, showing sharp boundaries with no intermixing of cells from different lineages. The relevance of the different embryological origins can be observed in many different aspects of SMC function 2, 3 (see Table 1). In addition, SMC responses to environmental signals, such as growth factors, have been observed to vary depending on the developmental origins of SMCs, and these responses are lineage-specific 2. On the other hand, SMC can undergo phenotypic changes, in vitro and in vivo, switching between secretory and contractile phenotypes, thus obscuring our conceptual reference to terminal differentiation in these cells. Several in vitro models to study SMC differentiation from stem cells have become available4-6. Moreover, growing evidence definitely indicates that vascular stem/progenitor cells play a major role in various cardiovascular diseases including atherosclerosis and angioplasty restenosis7. In this review we will summarize current well established in vitro cellular models available to study SMC differentiation from stem cells according to their developmental origins (see Table 2 and Figure 1) and further discuss relevant mechanisms underlying SMC specific differentiation from stem cells.

Table 1. Developmental origins of vascular SMCs.

| Origin | VSMC location | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Neural crest | pharyngeal arch arteries, including ascending aorta, aortic arch, innominate, left and right carotid arteries and right subclavian artery | 95, 96 |

| Proepicardium | coronary vessels | 95, 97 |

| Serosal mesothelium | mesenteric vasculature | 98 |

| Secondary heart field | base of the aorta and pulmonary trunk | 99, 100 |

| Somites | descending thoracic aorta | 101, 102 |

Table 2. Summary of in vitro cellular models to study SMC differentiation.

| Model | Origin | Treatment | SMMHC | Contractile | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C3H/10T1/2 cells | Mouse mesoderm | TGF-β1 | yes | not tested | 4 |

| Monc-1 cells | Mouse neural crest | Serum or TGF-β | yes – SM1 isoform | yes | 5, 34 |

| JoMa1 cells | Mouse neural crest | TGF-β | not tested | not tested | 38 |

| A404 | Mouse pluripotent embryonal carcinoma | atRA followed by puromycin | yes – SM1 isoform | not tested | 6 |

| ESC-EB | Mouse | atRA and db-cAMP | yes –SM2 isoforms | yes | 20, 21 |

| ESC(SMAA or SMMHC promoter/puromycin resistance gene-EB | Mouse | puromycin | yes | yes | 22 |

| ESC-EB followed by magnetic selection of CD34+ cells | Human | PDGF-BB | yes | yes | 23 |

| ESC-EB outgrowth | Human | Combination of media change and different extracellular matrix environments | yes | yes | 24 |

| ESC/iPS adherent monolayer | Mouse and human | atRA | YES | yes | 27, 28 |

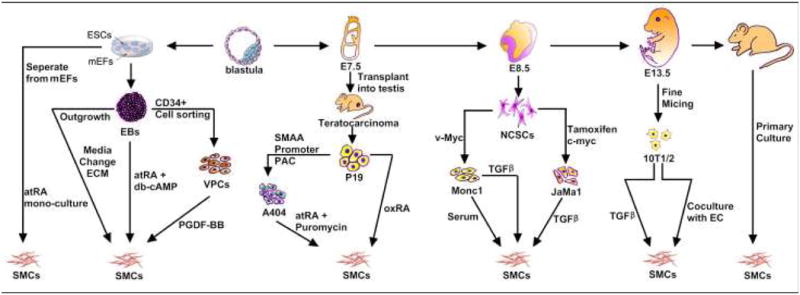

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of cellular models available to study SMC differentiation and their embryonic origins.

ESCs, embryonic stem cells; mEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; SMCs, smooth muscle cells; EC, endothelium cells; NCSC, neural crest stem cells; VPC, vascular progenitor cell; ECM, extracellular matrix; TGF, transforming growth factor; RA, retinoid acid; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor.

Approaches to Smooth Muscle Cell Differentiation in vitro

Embryonic Stem Cell-based Models

P19 and A404

The P19 cell line was derived from cell cultures established from the primary tumor of a teratocarcinoma that formed upon transplantation of a 7.5 day old mouse embryo into the testis 8, 9 and appear to use similar mechanisms as normal embryonic stem cells to differentiate 8. Studies have shown that P19 cells, upon treatment with retinoic acid (RA, 10-6M for 48h) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 7.5% FBS (following 5-7d), differentiate into fibroblast-like cells that express smooth muscle α-actin (ACTA2) 10, acquire calcium influx features and respond to phenylephrine, angiotensin II and endothelin11. However, P19 differentiation into SMCs in response to RA is not highly efficient with less than 1-5% differentiation ratio (Blank and Owens unpublished data) 6, thus requiring additional enrichment methods to increase the yield of SMCs 11.

Multipotent A404 cells are a P19-derived clonal cell line which has ACTA2 promoter/intron-driven puromycin resistance gene 6. When A404 cells are treated with all-trans RA (atRA, 10-6M for 2d) followed by puromycin (0.5 μg/mL for 2 or 5d), they efficiently differentiate into SMC with more than 90% of cells expressing ACTA2 and calponin (CNN1)12 or SM myosin heave chain (MHY11) 6. Additionally, the SMC transcription factor myocardin (MYOCD, an important transcription factor for the regulation of SM-specific genes13, 14) is induced and only the SM1 isoform of MHY11, a marker of late differentiation15, 16, is expressed in this model. A404 cells are an excellent in vitro cellular model to study the regulation of SMC-specific genes during the early steps of SMC differentiation. However, it should be kept in mind that the ACTA2 promoter was introduced to select for a small fraction of P19 cells with a higher propensity for SMC differentiation.

Embryoid Body differentiation system

Embryoid body (EB) cultures were originally used as a method to differentiate embryonic carcinoma cells 17. EBs are a spontaneously self-assembling 3-dimentional aggregate of pluripotent stem cells grown in vitro in a suspension culture 18. EBs can form all three germ-layers and mimic the processes of early embryonic development 19. Embryonic carcinoma cells 17 as well as ESC 19 can form EBs in vitro. Mouse ESCs can be differentiated into SMCs with the EB method 20-22. Treatment with atRA (10-8M) and dibutyryl-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (db-cAMP, 0.5×10-3M) after EB formed for 6d lead to spontaneously contracting SM-like cells in 67% of the EBs compared to 10% of the control EBs 20, 21. These SM-like cells express ACTA2 as well as the vascular MHY11 isoform and depict electrophysiological properties and response to vasoactive agonists such as angiotensin II, endothelin-1 and KCl similar to those of VSMCs, indicating that these cells are VSMCs instead of visceral SMCs20. One limitation of EB-derived SMCs is that only a fraction of the cells within the EB differentiate into SMC, making it difficult to further analyze the SMCs within EBs20, 21. Other strategies have to be applied to enrich SMCs with this system22. Moreover, in vivo studies showed that the purified SMCs lead to the formation of teratomas when selected with puromycin for short periods of times prior to implantation in mice. Longer puromycin selection times eliminated the formation of teratomas, yet the SMCs were not able to form blood vessels in vivo 22.

Human ESCs can also be differentiated into SMCs with the EB method 23, 24. Isolated CD34+ vascular progenitor cells could differentiate into SM-like cells when treated with platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB, 50ng/mL for 3 passages) and showed spindle-shape morphology. Meanwhile, the cells expressed the SM maker genes ACTA2, MHY11, SM22α (TAGLN), CNN1 and caldesmon and were able to contract in response to carbachol 23. Yet, it is important to note that these cells also expressed the endothelial markers angiopoietin-2 and Tie2, implying that the SMC differentiation process was incomplete. Interestingly, subcutaneous injection of a mixture of endothelial cell-like and SMC-like cells isolated from human EBs into nude mice showed that these cells could form human microvessels in vivo 23. Our group used an alternative approach to differentiate SMCs from EBs derived from human ESCs. In this method, outgrowth from EBs was isolated and differentiated into SMCs using smooth muscle growth medium (SMGM) in combination with matrigel and subsequently DMEM + 5%FBS on gelatin coat 24. The SMCs derived from this protocol showed elongated spindle-shaped morphology and expressed ACTA2, MHY11, TAGLN, calponin and h-caldesmon. The efficiency of this method, as analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis, was of 55.26% for MHY11 and 96.81% for ACTA2 24. Further analysis of the SMCs derived from human EBs showed that they contracted in response to carbachol and KCl treatment, indicating that the SMCs were functional 24.

One of the major advantages of the EB method is that it mimics the processes observed during early embryonic development, including the expression of essential regulatory molecules occurring in the same time course as observed during embryogenesis 19, 25. Additionally, it is possible to use genetically manipulated ESCs to study genes that lead to embryonic lethality in vivo 18. Therefore, EBs allow for the unique opportunity to study molecular mechanisms of SMC differentiation in an environment that recapitulates early embryonic processes, but in vitro. On the other hand, there are also limitations with this method. First, differentiation methods that rely on the addition of soluble factors to the culture media have the disadvantage that only the cells on the exterior of the EB are in direct contact with the media, and the cells within the EBs will not be exposed to the soluble factors 18. Second, many cell types are present within the EBs and methods to separate SMCs from other cell types are needed 22. Finally, heterogeneity within EBs and between EBs occurs due to a lack of axial specification or patterning during differentiation 18, 26.

ESC adherent monolayer culture differentiation system

ESCs and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells have been successfully differentiated into SMCs using an adherent monolayer culture differentiation system 27, 28. In this model, ESCs are separated from the feeder mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and cultured in monolayer in the presence of atRA (10-5M) leading to their differentiation into SMCs at an efficiency between 41-65% for MHY11 expression 27, 28. Morphological change into a SMC-like phenotype is accompanied by the expression of SM marker genes (ACTA2, TAGLN, CNN1 and MHY11) 27, 28 and characteristics of functional SMCs, including: 1) contraction in response to the muscarinic agonist carbachol 27, 28; 2) autonomous SM-like contraction frequency after prolonged culture 27; and 3) functional calcium responses to the vasoconstrictors caffeine, endothelin and the depolarizing agent KCl 28. ESC single layer culture plus stem cell antigen-1-positive (Sca-1) cell selection with collagen IV-based differentiation model also showed the advantage of single layer culture strategy29, 30. With this model, sorted Sca-1+ cells differentiated toward SMCs29 and endothelial cells30. A highly purified SMCs population (>95%) expressing high levels of SMC markers could be achieved after 30 days of continued culture29.

Unlike in EBs, in monolayer models individual ESC is equally exposed to stimuli leading to fairly homogeneous and high-yield differentiation. It can be used with different types of ESCs 27-29 for the study of early events in their differentiation into SMC differentiation. Yet, since this differentiation strategy is not three-dimensional-based as embryogenesis, the spatial gene regulation cues regarding SMC differentiation will be missed. Although ESCs provide a great model to study early stages of development, when these cells are induced to differentiate into a specific lineage, it is unknown whether certain intermediate lineages are skipped and the potential effects of skipping these steps on the differentiation process. This method also works with iPS cells 28, providing a unique chance to generate SMC in vitro from iPS isolated from individual patients suffering from diseases resulting from genetic deficient SMCs. Genetic correction of SMCs in vitro or their modulation could be the basis for future cell- and tissue-based therapy.

Mesoderm Derived Models

C3H/10T1/2 cells

The 10T1/2 cell line was established from 14-17 day old whole C3H mouse embryos 31 and C3H/10T1/2 cells can differentiate into SMCs by being co-cultured with endothelial cells or treated with transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-β1, 1 ng/ml) for 24-48h, evidenced by a phenotypic change from a polygonal into a spindled-shaped phenotype, accompanied by the expression of SM-specific markers (ACTA2, MHY11, CNN1 and TAGLN) 4. This model is very attractive for the studies of SMC differentiation because of (1) availability for purchase of the cells from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), (2) undemanding culture conditions, and (3) easy and quick differentiation using TGF-β1, allowing for fast results.

Nonetheless, it has been suggested that 10T1/2 cells cannot fully differentiate into SMCs upon TGF-β1 treatment but rather to myofibroblasts 3 that do not express MYOCD and showing inconsistency in MHY11 expression 4, 14, 32. These conflicting reports on expression of SM markers in this model are likely due to differences in the culturing methods and manipulation of these cells in different laboratories4. Albeit these caveat, this model is still widely used as a quick method in gain- and loss-of-function studies and to determine whether certain regulatory molecules can induce SMC differentiation.

Neural Crest Stem Cell Derived Models

Monc-1 cells

Monc-1 is an immortalized neural crest cell line that was generated by retroviral transfection of a primary culture of mouse neural crest cells with the v-myc gene 33. Two in vitro SMC differentiation models use Monc-1 cells: a) with 10% fetal bovine serum 5 and b) with TGF-β (5ng/ml for 3d) 34, both resulting in induction of expression of SM markers 5, 34, including the MHY11 and smoothelin (SMTN) markers of highly differentiated stage SMC15, 35, 36. However, SMCs derived from serum treated Monc-1 cells depicted a flattened morphology, similar to the synthetic phenotype of SMC, lack response to carbachol 5, 34 and expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin was not completely eliminated 34, suggesting only a partial epithelial to mesenchymal transformation. In contrast, SMCs derived from TGF-β1 treatment of Monc-1 cells were elongated spindle-shaped morphology34, characteristic of the contractile state of SMC, contracted in response to carbachol and lost expression of E-cadherin 34, indicating that TGF-β treatment of Mon-1 cells seems to be a better model to study differentiation from a neural crest lineage into functional SMC.

While a rapid and reproducible model resulting in the expression of multiple SM markers including MHY11 and SMTN, Monc-1 cells have to be kept in a chemically defined media, referred to as complete medium, quite complicated to prepare in order to retain their undifferentiated state 5, 34, 37. Although a very attractive method to study the differentiation of neural crest-derived SMCs in vitro, limited follow-up studies are yet available to define the Monc-1 as a bona fide SMC differentiation system. Thus, for instance, Monc-1 cells were immortalized by constitutive expression of myc 33, 38. The differentiation program in Monc-1 cells did not seem to be overtly disturbed by the constitutive expression of v-myc, based on the observations that Monc-1 cells could differentiate into neuron, glia, melanocytes and SMCs 5, 33, 34. However, potential effects of v-myc constitutive expression during differentiation on the molecular and cellular processes of the SMC differentiation program remains to be addressed.

JoMa1 cells

The JoMa1 cells are immortalized neural crest stem cells that were derived from neural crest primary cultures from a transgenic mouse line harboring conditional tamoxifen inducible expression of c-myc. Withdrawal of tamoxifen from the culture media, resulting in loss of c-myc expression, and treatment of the JoMa1 cells with TGF-β (1 ng/ml for 6d) induce differentiation into SMCs, as indicated by morphology change and expression of ACTA2 (90% of cells), SM γ-actin and low levels of CNN1 38. A clonally derived subline of JoMa1, termed JoMa1.3, showed a more pure SMC lineage expressing higher levels of CNN1 than its parental line upon TGF-β1 treatment 38.

Unlike in Monc-1 cells, in JoMa1 and JoMa1.3 cells expression of c-myc subsides when these cells are induced to differentiate into SMCs 38 therefore avoiding potential problems with interference of this oncogene with the differentiation program. In that regard, induction of differentiation in the presence of tamoxifen which maintains expression of c-myc in JoMa1 and JoMa1.3 cells lead to cell death, showing incompatibility between the proliferation and differentiation signals in this cell background 38. Although an emerging attractive method to study SMC differentiation from a neural crest lineage, JoMa1 presents similar disadvantages as the Monc-1 system in that it requires a chemically defined media to keep the cells in an undifferentiated state and additional follow up studies may be required to further establish this method.

In summary, a variety of in vitro cellular models are currently available to study SMC differentiation. Nonetheless, their relative advantages together with their intrinsic limitations should be taken into careful consideration to select the model that best suits the experimental questions being addressed.

Mechanisms that Control Smooth Muscle Cell Differentiation in Vitro

SMC differentiation from stem cells is a complex and, at least so far, poorly defined process. Accumulating evidence from the different stem cell-SMC differentiation systems has revealed that a delicately coordinated molecular network orchestrates the program of SMC differentiation from stem cells (Figure 2). Numerous layers of regulation (e.g. epigenetic modifications, gene transcription and translation, post-transcription and post-translation) and various signaling pathways and molecules, such as MYOCD-serum reactive factor (SRF) complex, extracellular matrix (ECM)39, retinoid receptor, TGF family (e.g. SMAD321, 40), Notch family41, reactive oxygen species (e.g. NOX442 and NRF343) and others (e.g. Pitx244 and PIAS145), play major roles in SMC differentiation from stem cells. The present review will not cover all recognized aspects of the mechanisms regulating SMC differentiation at large but will rather focus on the recent progress in the specific field of stem cell differentiation into SMC.

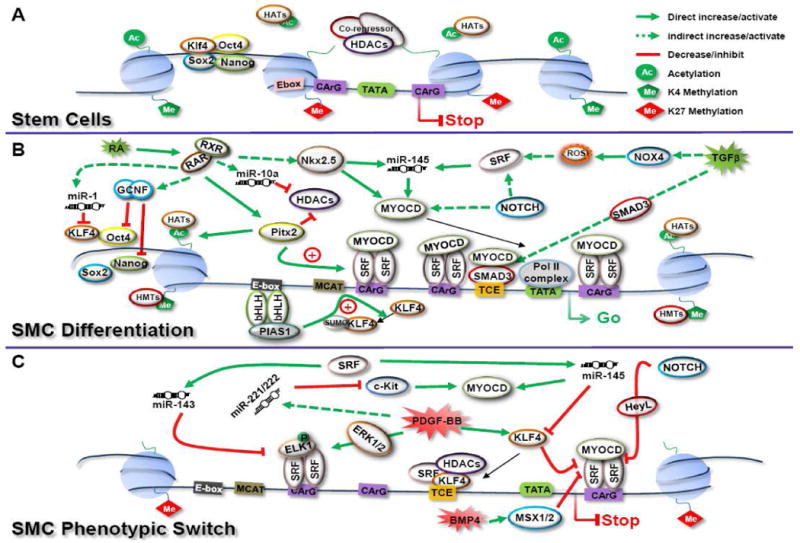

Figure 2. Proposed model for the regulation of SMC specific genes during ESC/SMC differentiation and phenotypic switching.

(A) In undifferentiated ESCs, Oct4, Sox2, Nanog and Klf4 form a core transcription complex maintaining the pluripotent network for stem cell self-renewal. Downstream genes associated with stem cell proliferation and pluripotency are actively transcribed marked with histone 3 lysine 4 methylation (H3K4me) and histone acetylation. Meanwhile, target genes co-occupied by the core transcription complex and encoding SMC specific genes are transcriptionally silent marked with H3K27me associated with the recruitment of HDACs and co-repressors at the regulatory regions of these SMC specific genes. As a result, the regulatory DNA sequence of these SMC specific genes are wrapped in compacted chromatin and blocked the access from MYOCD-SRF complex and subsequent activation. (B) SMC differentiation from ESCs has been shown to be mediated by multiple mechanisms. Extracellular stimuli (including retinoid acid and various growth factors) initiate the permanent shutdown of activation of the pluripotent core transcription complex on pluripotent genes and lead to downstream domino cascades. Ultimately, these serial programs result in dramatic chromatin modification in these regions, marked by histone acetylation and H3K4me and release the compacted chromatin containing the regulatory domain of SMC specific genes to expose the regulatory domains to diverse activator networks, including transcription factors, reactive oxygen species, miRNAs and nuclear receptors, etc. The transcription of most SMC specific genes is mainly activated by SRF binding to CArG boxes located within the regulatory region of SMC specific genes, enhanced by MYOCD. Additional elements further enhance transcription, such as bHLH transcription factors via PIAS-1 and TGFβ control element via SMAD3. (C) SMC phenotypic switching is initiated by various extracellular cues. During this process, transcription of SMC specific markers is downregulated and SMCs undergo the phenotypic transformation from contractile to proliferative/synthetic status. The regulatory networks involved into this change include histone modification that reprogram to deacetylation and H3K27me further closing active chromatin; phosphorylation-ELK1 by ERK1/2 and thereby blocking MYOCD interactions with SRF; KLF-4 and HeyL blocking SRF binding to CArG boxes; and microRNA interference operating post-trasncriptionally on critical regulators. Oct4, octamer-binding protein 4; Sox2, SRY-box containing gene 2; KLF-4, Kruppel like factor 4; HATs, histone acetyltransferases; HDACs, histone deacetylases; HMTs, histone methylation transferases; RXR, retinoid x receptor; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; GCNF, germ cell nuclear factor; miR, microRNA; Pitx2, paired-like homeodomain 2; Nkx2.5, NK2 transcription factor related, locus 5; MYOCD, myocardin; SRF, serum response factor; NOX4, NADPH oxidase 4; PIAS-1, protein inhibitor of activated STAT-1; Pol II, polymerase II; ELK1, ETS domain-containing protein 1; HeyL, hairy/enhancer-of-split related with YRPW motif-like; SMAD3, mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3; Msx, muscle-segment homeobox like protein; TCE, TGFβ control element. bHLH, basic helix-loop-helix; RA, retinoid acid; TGFβ, transforming growth factor β; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; BMP4, bone morphogenetic protein 4; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Me, methylation; Ac, acetylation; SUMO, sumoylation.

Retinoid signaling

RA is a metabolite of vitamin A and one of the most important regulatory factors of gene transcription46. atRA binds to RARα, β, or γ in the nucleus which, in turn, can bind to one of the RXRs (RXRα, β, or γ) and the RXR/RAR heterodimer complex binds to DNA and leads to the activation of RA responsive genes47. At certain RA-responsive genes, the RXR/RAR complex binds to highly compacted, higher-order chromatin, allowing RNA polymerase II and other general transcription factors to activate transcription48 and leading to cell lineage-specific, epigenetic modifications at those genes49, 50. Studies on the effects of retinoids on vasculogenesis have indicated that low or absent levels of atRA have profound consequences for normal vascular development46. A strong RA response signal was predominantly detected in the developing ductus arteriosus and the signal colocalized with the expression of the adult-specific MHY11 isoform, SM251. Direct evidence implicating atRA in vasculogenesis is offered from studies in retinoid receptor knockout mice although, not every single–retinoid receptor null mice showed vasculogenesis deficiency, partially due to generalized growth deficiency (like in RARα−/− or RARγ−/−) and possible functional compensation by other retinoid receptor 52-54.

As indicated in the earlier sections of this review, a number of in vitro studies have shown that atRA positively influence the SMC differentiation program from stem cells. In the P19 embryonic cell model system of SMC differentiation, atRA was shown to stimulate several SMC markers, including ACTA2 and MHY1111, 55, 56 and the expression of MHox11, a homeodomain-containing transcription factor that potentiates the expression of ACTA2. An elevation in the expression of ACTA2 and MHY11 was also observed in atRA-treated ESCs20, 28. Our studies have shown that atRA triggers miR-10a and miR-1 expression in ESCs and subsequently represses HDAC4 and KLF4, respectively and leads to SMC differentiation57, 58. On the other hand, the presence of atRA dramatically increased the frequency of contracting SMCs from ESCs20. These data suggests an important positive role for atRA in the SMC differentiation from stem cells.

Epigenetics and HDAC signaling

Several studies indicate that ESCs are characterized by compact chromatin and less transcription activity compared to differentiated cells. As differentiation advances, chromatin changes to a repressed and inactive state59. Specific residues in the N-terminal tails of histones are prone to numerous reversible post-translational modifications including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation60 and proteolysis61. These modifications are achieved via different chromatin modifying enzyme complexes with opposing functions, which are responsible for the dynamic behavior of chromatin and include histone acetyltranferases (HATs), histone deacetylases (HDACs), DNA methyl transferases (DNMT)62 and histone demethylases63. Recent studies suggest that a “histone bivalent” model (active and inactive histone modifications) regulates ESC status by controlling gene expression for lineage-specific genes, which are silent in pluripotent ESCs, but may be expressed upon differentiation64-67. The suppressive modifications (H3K27me3) and activating marks (H3K4me3 and H3K9ac3) in various cell lineage specific gene promoters have been identified in differentiation66, 67. This model implies that the key developmental-control genes are present in a “primed or poised status” in ESCs as defined by opposite combinations of histone alterations to help maintain pluripotency and suppress developmental gene expression66, 67. This primed or poised epigenetics status must be eliminated in pluripotent stem cells to trigger early development, and later within tissue specific differentiation. It remains unknown how these cues exactly operate in different cell types.

The latest and most detailed descriptions regarding the relationship between epigenetics and SMC differentiation come mostly from studies of SMC phenotypic switch68. Yet, it could be proposed that a mechanism akin could be at play in regulating ESC differentiation into SMCs (Figure 2). MYOCD is a critical SMC specific coactivator of SRF which forms dimer and binds to the CArG element located within SMC specific genes13, 69. The ability and stability of MYOCD-SRF complex binding to regulatory sequence of SMC specific genes substantially controls SMC specific gene expression 68. Several epigenetic components have been shown to affect SMC differentiation by changing the association between MYOCD-SRF complex and regulatory DNA sequence70-72. Among these, HDAC7 was identified to undergo alternative splicing during SMC differentiation from ESCs and led to the enhancement of the binding between SRF dimer and MYOCD. As the result, MYOCD-SRF complex was recruited to the TAGLN promoter and activated SMC marker gene expression 73. Simultaneously, the studies have suggested that the modification of histone features of chromatin containing SMC genes, in response to extracellular cues, in parallel alters the accessibility of MYOCD-SRF complex to DNA sequence of SMC specific genes68, 72, 74. For instance, the status of SMC-specific H3K4Me2 and H4 acetylation at CArG boxes is dynamically regulated corresponding PDGF-BB treatment68. HDAC p300 can associates with the transcription activation domain of MYOCD and induce the expression of SMC genes, whereas, HDAC5 suppress the expression of SMC genes through interaction with different domains of MYOCD75. Moreover, the interaction between KLF4, ELK-1, and HDACs which coordinately mediates the regulation of the SMC specific gene expression has been demonstrated74. This interaction was accompanied by hypoacetylation of histone H4 at the ACTA2 promoter, via recruitment of HDAC2 and HDAC574. These intricate interactions provide harmonized regulatory control over SMC phenotype along with diverse enviroments68.

Although it is known that HDACs play roles in the differentiation of stem cells towards SMCs76, further studies will be required to determine the relationships between histone de/acetylation and SMC differentiation modulators in the stem cell/SMC differentiation system.

Extracellular matrix signaling

Differentiation and cell fate decisions are controlled by their surrounding microenvironment, named stem cell niche77. Stem cell niches are anatomically localized in protected sites of tissues and regulate the cell adherence, growth, migration, apoptosis, and differentiation via external signals77, 78. Among the component of niches, the extracellular matrix (ECM) provides a chemical and mechanical structure, which is essential for development and for responses to physiological/pathophysiological signals79. ECM structure is dictated by the interaction of collagen fibers with each other and with laminin, as well as high-molecular-weight proteoglycans. Furthermore, studies have proven that ECM can modulate the bioactivities of growth factors and cytokines, such as TGF-β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and PDGF78. In addition to the structural stability provided by the cell-secreted ECM constituents, cells residing in the ECM can influence ECM signaling by producing enzymes that cause proteolytic modification of proteins and growth factors in the ECM80.

Previous studies have demonstrated the 3D collagen matrix mimicked such 3D tissue structure in vitro, and induced ESCs to differentiate into various cell lineages81. Collagen IV has been used as coating media to promote vascular progenitor cell differentiation into SMCs in the presence of serum as well as a feeder cell layer with the addition of VEGF or PDGF82, 83. Further studies determined that collagen IV coating facilitated and enriched the differentiation of stem cell antigen-1-positive (Sca-1) vascular progenitor cells from ESCs29. Our group recently developed nanofibrous (NF) poly-L-lactide (PLLA) scaffolds and found that tubular NF PLLA scaffold preferentially supported contractile phenotype of human aorta SMCs under in vitro culture conditions, as evidenced by elevated gene expression levels of SMCs contractile markers including MHY11, SMTN and MYOCD. In vivo subcutaneous implantation studies confirmed human aorta SMC differentiation in the implants82. These observations revealed that both ECM is essential during embryonic SMC differentiation.

miRNA signaling

miRNA is a class of highly conserved, single-stranded, noncoding small RNAs proven to be involved into widespread cellular functions, such as differentiation, proliferation, migration, and apoptosis84, 85. Mature miRNAs associate with a nuclease complex to target mRNAs for the purpose of mediating mRNA silencing primarily through their degradation through Argonaute-catalysed mRNA cleavage, as emerging evidences indicate86, 87, and translational repression84, 88.

Our group has found that miRNAs underwent dynamic changes during the differentiation process from ESCs to SMCs57, 58. Among those, miR-1 and miR-10a showed upregulation and blockade with anti-miR-1 or anti-miR-10a repressed MSC differentiation, evidenced by a significantly reduced VSMC differentiation percentage. Furthermore, individual duplexes between miRNA and potential targets were identified for miR-1:KLF4 and miR-10a:HDAC457, 58. Interestingly, miR-10a activity was regulated by NF-κB in this model of SMC differentiation from ESCs. This result suggests miRNAs play a critical role to regulate SMC differentiation from ESCs in vitro57, 58. Additionally, after the miR-143/145 cluster is found to be one of regulator involved with SMC phenotypic switch89, this cluster has been shown to regulate SMC differentiation from stem cells/progenitor90-93. Deletion of miR-145 impaired the conversion from fibroblasts to VSMCs induced by MYOCD and repressed expression of the SMC contractile apparatus. In addition, overexpression of miR-145 enhanced JoMa1.3 cells differentiation into the VSMC lineage90. The number of contractile VSMCs significantly decreased and the number of synthetic VSMCs remarkably increased in the aorta and the femoral artery in miR-143/miR-145 double knock-out mice, while, simultaneously, the number of noncontractile, proliferating precursors increased 91-93. Furthermore, VSMCs within miR-143/145 double mutant artery showed a significant inhibition in the expression of SMC-specific differentiation markers 91, 92.

Direct evidence that miRNAs are fundamental regulators of VSMC differentiation came from the study of a mouse conditional knockout of the rate-limiting enzyme Dicer in VSMCs of blood vessels that results in late embryonic lethality at E16 to 1794. Loss of VSMC Dicer results in dilated, thin-walled blood vessels, which may be due to a reduction in cellular proliferation. Moreover, the resultant VSMCs exhibited loss of contractile apparatus and ensuing impaired contractility which could be partially rescued by overexpression of miR-145 or MYOCD94. This study further supports that Dicer-dependent miRNAs are essential for VSMC development and function by regulating differentiation and indicates that miRNAs play critical roles in maintaining the differentiated phenotype of VSMCs.

Perspectives

Understanding the detailed mechanisms of stem cell differentiation into SMCs is essential not only for elucidating basic aspects of vascular biology but also exploring clinical therapeutic methods. Although a variety of in vitro cellular models are available to study detailed mechanisms of SMC differentiation, there are two important considerations that should be taken into account when deciding which experimental system to use. Firstly, the variety of embryonic origins of SMCs as discussed above. Thus, it is proposed that individual regulatory regimes regarding differentiation control may exist in SMCs of disparate embryonic origin and therefore, the choice of cellular models to address the specific ideas may make significant difference. Secondly, the intrinsic limitations of in vitro culture of SMCs should be taken into consideration. It is important to keep in mind that it is not known to what extent in vitro differentiation models recapitulate SMC differentiation and maturation in vivo. Therefore, although in vitro models are a very powerful and complementary tool to provide insights into the molecular mechanisms of SMC differentiation in a controlled environment, in vivo experiments are needed to support the findings from the various in vitro models.

References

- 1.Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Majesky MW. Developmental basis of vascular smooth muscle diversity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1248–1258. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida T, Owens GK. Molecular determinants of vascular smooth muscle cell diversity. Circ Res. 2005;96:280–291. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000155951.62152.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirschi KK, Rohovsky SA, D'Amore PA. PDGF, TGF-beta, and heterotypic cell-cell interactions mediate endothelial cell-induced recruitment of 10T1/2 cells and their differentiation to a smooth muscle fate. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:805–814. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain MK, Layne MD, Watanabe M, Chin MT, Feinberg MW, Sibinga NE, Hsieh CM, Yet SF, Stemple DL, Lee ME. In vitro system for differentiating pluripotent neural crest cells into smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5993–5996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.5993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manabe I, Owens GK. Recruitment of serum response factor and hyperacetylation of histones at smooth muscle-specific regulatory regions during differentiation of a novel P19-derived in vitro smooth muscle differentiation system. Circ Res. 2001;88:1127–1134. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams B, Xiao Q, Xu Q. Stem cell therapy for vascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2007;17:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McBurney MW. P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. Int J Dev Biol. 1993;37:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McBurney MW, Rogers BJ. Isolation of male embryonal carcinoma cells and their chromosome replication patterns. Dev Biol. 1982;89:503–508. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudnicki MA, Sawtell NM, Reuhl KR, Berg R, Craig JC, Jardine K, Lessard JL, McBurney MW. Smooth muscle actin expression during P19 embryonal carcinoma differentiation in cell culture. J Cell Physiol. 1990;142:89–98. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041420112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blank RS, Swartz EA, Thompson MM, Olson EN, Owens GK. A retinoic acid-induced clonal cell line derived from multipotential P19 embryonal carcinoma cells expresses smooth muscle characteristics. Circ Res. 1995;76:742–749. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.5.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spin JM, Nallamshetty S, Tabibiazar R, Ashley EA, King JY, Chen M, Tsao PS, Quertermous T. Transcriptional profiling of in vitro smooth muscle cell differentiation identifies specific patterns of gene and pathway activation. Physiol Genomics. 2004;19:292–302. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00148.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Kitchen CM, Streb JW, Miano JM. Myocardin: a component of a molecular switch for smooth muscle differentiation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:1345–1356. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshida T, Sinha S, Dandre F, Wamhoff BR, Hoofnagle MH, Kremer BE, Wang DZ, Olson EN, Owens GK. Myocardin is a key regulator of CArG-dependent transcription of multiple smooth muscle marker genes. Circ Res. 2003;92:856–864. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000068405.49081.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miano JM, Cserjesi P, Ligon KL, Periasamy M, Olson EN. Smooth muscle myosin heavy chain exclusively marks the smooth muscle lineage during mouse embryogenesis. Circ Res. 1994;75:803–812. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.5.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owens GK. Regulation of differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:487–517. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin GR, Evans MJ. Differentiation of clonal lines of teratocarcinoma cells: formation of embryoid bodies in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:1441–1445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.4.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bratt-Leal AM, Carpenedo RL, McDevitt TC. Engineering the embryoid body microenvironment to direct embryonic stem cell differentiation. Biotechnology Progress. 2009;25:43–51. doi: 10.1002/btpr.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doetschman TC, Eistetter H, Katz M, Schmidt W, Kemler R. The in vitro development of blastocyst-derived embryonic stem cell lines: formation of visceral yolk sac, blood islands and myocardium. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1985;87:27–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drab M, Haller H, Bychkov R, Erdmann B, Lindschau C, Haase H, Morano I, Luft FC, Wobus AM. From totipotent embryonic stem cells to spontaneously contracting smooth muscle cells: a retinoic acid and db-cAMP in vitro differentiation model. Faseb J. 1997;11:905–915. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.11.9285489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinha S, Hoofnagle MH, Kingston PA, McCanna ME, Owens GK. Transforming growth factor-beta1 signaling contributes to development of smooth muscle cells from embryonic stem cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1560–1568. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00221.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinha S, Wamhoff BR, Hoofnagle MH, Thomas J, Neppl RL, Deering T, Helmke BP, Bowles DK, Somlyo AV, Owens GK. Assessment of contractility of purified smooth muscle cells derived from embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1678–1688. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreira LS, Gerecht S, Shieh HF, Watson N, Rupnick MA, Dallabrida SM, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Langer R. Vascular progenitor cells isolated from human embryonic stem cells give rise to endothelial and smooth muscle like cells and form vascular networks in vivo. Circ Res. 2007;101:286–294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.150201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie CQ, Zhang J, Villacorta L, Cui T, Huang H, Chen YE. A highly efficient method to differentiate smooth muscle cells from human embryonic stem cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:e311–312. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.154260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishikawa S, Jakt LM, Era T. Embryonic stem-cell culture as a tool for developmental cell biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:502–507. doi: 10.1038/nrm2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rathjen J, Rathjen PD. Mouse ES cells: experimental exploitation of pluripotent differentiation potential. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2001;11:587–594. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang H, Zhao X, Chen L, Xu C, Yao X, Lu Y, Dai L, Zhang M. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into smooth muscle cells in adherent monolayer culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie CQ, Huang H, Wei S, Song LS, Zhang J, Ritchie RP, Chen L, Zhang M, Chen YE. A comparison of murine smooth muscle cells generated from embryonic versus induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:741–748. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao Q, Zeng L, Zhang Z, Hu Y, Xu Q. Stem cell-derived Sca-1+ progenitors differentiate into smooth muscle cells, which is mediated by collagen IV-integrin alpha1/beta1/alphav and PDGF receptor pathways. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C342–352. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00341.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao Q, Zeng L, Zhang Z, Margariti A, Ali ZA, Channon KM, Xu Q, Hu Y. Sca-1+ progenitors derived from embryonic stem cells differentiate into endothelial cells capable of vascular repair after arterial injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2244–2251. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000240251.50215.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reznikoff CA, Brankow DW, Heidelberger C. Establishment and characterization of a cloned line of C3H mouse embryo cells sensitive to postconfluence inhibition of division. Cancer Res. 1973;33:3231–3238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunelli S, Tagliafico E, De Angelis FG, Tonlorenzi R, Baesso S, Ferrari S, Niinobe M, Yoshikawa K, Schwartz RJ, Bozzoni I, Cossu G. Msx2 and necdin combined activities are required for smooth muscle differentiation in mesoangioblast stem cells. Circ Res. 2004;94:1571–1578. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000132747.12860.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao MS, Anderson DJ. Immortalization and controlled in vitro differentiation of murine multipotent neural crest stem cells. J Neurobiol. 1997;32:722–746. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19970620)32:7<722::aid-neu7>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen S, Lechleider RJ. Transforming growth factor-beta-induced differentiation of smooth muscle from a neural crest stem cell line. Circ Res. 2004;94:1195–1202. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126897.41658.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Loop FT, Schaart G, Timmer ED, Ramaekers FC, van Eys GJ. Smoothelin, a novel cytoskeletal protein specific for smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:401–411. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.2.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Eys GJ, Voller MC, Timmer ED, Wehrens XH, Small JV, Schalken JA, Ramaekers FC, van der Loop FT. Smoothelin expression characteristics: development of a smooth muscle cell in vitro system and identification of a vascular variant. Cell Struct Funct. 1997;22:65–72. doi: 10.1247/csf.22.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stemple DL, Anderson DJ. Isolation of a stem cell for neurons and glia from the mammalian neural crest. Cell. 1992;71:973–985. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90393-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maurer J, Fuchs S, Jager R, Kurz B, Sommer L, Schorle H. Establishment and controlled differentiation of neural crest stem cell lines using conditional transgenesis. Differentiation. 2007;75:580–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2007.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki S, Narita Y, Yamawaki A, Murase Y, Satake M, Mutsuga M, Okamoto H, Kagami H, Ueda M, Ueda Y. Effects of extracellular matrix on differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells into smooth muscle cell lineage: utility for cardiovascular tissue engineering. Cells Tissues Organs. 2010;191:269–280. doi: 10.1159/000260061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiu P, Ritchie RP, Fu Z, Cao D, Cumming J, Miano JM, Wang DZ, Li HJ, Li L. Myocardin enhances Smad3-mediated transforming growth factor-beta1 signaling in a CArG box-independent manner: Smad-binding element is an important cis element for SM22alpha transcription in vivo. Circ Res. 2005;97:983–991. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000190604.90049.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurpinski K, Lam H, Chu J, Wang A, Kim A, Tsay E, Agrawal S, Schaffer DV, Li S. Transforming growth factor-beta and notch signaling mediate stem cell differentiation into smooth muscle cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:734–742. doi: 10.1002/stem.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao Q, Luo Z, Pepe AE, Margariti A, Zeng L, Xu Q. Embryonic stem cell differentiation into smooth muscle cells is mediated by Nox4-produced H2O2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C711–723. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00442.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pepe AE, Xiao Q, Zampetaki A, Zhang Z, Kobayashi A, Hu Y, Xu Q. Crucial role of nrf3 in smooth muscle cell differentiation from stem cells. Circ Res. 2010;106:870–879. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.211417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shang Y, Yoshida T, Amendt BA, Martin JF, Owens GK. Pitx2 is functionally important in the early stages of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:461–473. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200711145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawai-Kowase K, Kumar MS, Hoofnagle MH, Yoshida T, Owens GK. PIAS1 activates the expression of smooth muscle cell differentiation marker genes by interacting with serum response factor and class I basic helix-loop-helix proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8009–8023. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8009-8023.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colbert MC. Retinoids and cardiovascular developmental defects. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2002;2:25–39. doi: 10.1385/ct:2:1:25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gudas LJ, Wagner JA. Retinoids regulate stem cell differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:322–330. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li G, Margueron R, Hu G, Stokes D, Wang YH, Reinberg D. Highly compacted chromatin formed in vitro reflects the dynamics of transcription activation in vivo. Mol Cell. 2010;38:41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoenfelder S, Sexton T, Chakalova L, Cope NF, Horton A, Andrews S, Kurukuti S, Mitchell JA, Umlauf D, Dimitrova DS, Eskiw CH, Luo Y, Wei CL, Ruan Y, Bieker JJ, Fraser P. Preferential associations between co-regulated genes reveal a transcriptional interactome in erythroid cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42:53–61. doi: 10.1038/ng.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mongan NP, Gudas LJ. Diverse actions of retinoid receptors in cancer prevention and treatment. Differentiation. 2007;75:853–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2007.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colbert MC, Kirby ML, Robbins J. Endogenous retinoic acid signaling colocalizes with advanced expression of the adult smooth muscle myosin heavy chain isoform during development of the ductus arteriosus. Circ Res. 1996;78:790–798. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.5.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kastner P, Grondona JM, Mark M, Gansmuller A, LeMeur M, Decimo D, Vonesch JL, Dolle P, Chambon P. Genetic analysis of RXR alpha developmental function: convergence of RXR and RAR signaling pathways in heart and eye morphogenesis. Cell. 1994;78:987–1003. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sucov HM, Dyson E, Gumeringer CL, Price J, Chien KR, Evans RM. RXR alpha mutant mice establish a genetic basis for vitamin A signaling in heart morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1007–1018. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krezel W, Dupe V, Mark M, Dierich A, Kastner P, Chambon P. RXR gamma null mice are apparently normal and compound RXR alpha +/-/RXR beta -/-/RXR gamma -/- mutant mice are viable. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9010–9014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suzuki T, Kim HS, Kurabayashi M, Hamada H, Fujii H, Aikawa M, Watanabe M, Watanabe N, Sakomura Y, Yazaki Y, Nagai R. Preferential differentiation of P19 mouse embryonal carcinoma cells into smooth muscle cells. Use of retinoic acid and antisense against the central nervous system-specific POU transcription factor Brn-2. Circ Res. 1996;78:395–404. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yao CC, Breuss J, Pytela R, Kramer RH. Functional expression of the alpha 7 integrin receptor in differentiated smooth muscle cells. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 13):1477–1487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.13.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang H, Xie C, Sun X, Ritchie RP, Zhang J, Chen YE. miR-10a contributes to retinoid acid-induced smooth muscle cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9383–9389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.095612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xie C, Huang H, Sun X, Guo Y, Hamblin M, Ritchie RP, Garcia-Barrio MT, Zhang J, Chen YE. MicroRNA-1 Regulates Smooth Muscle Cell Differentiation by Repressing Kruppel-Like Factor 4. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:205–210. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiblin AE, Cui W, Clark AJ, Bickmore WA. Distinctive nuclear organisation of centromeres and regions involved in pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3861–3868. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schones DE, Zhao K. Genome-wide approaches to studying chromatin modifications. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:179–191. doi: 10.1038/nrg2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duncan EM, Muratore-Schroeder TL, Cook RG, Garcia BA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Allis CD. Cathepsin L proteolytically processes histone H3 during mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation. Cell. 2008;135:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jackson M, Krassowska A, Gilbert N, Chevassut T, Forrester L, Ansell J, Ramsahoye B. Severe global DNA hypomethylation blocks differentiation and induces histone hyperacetylation in embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8862–8871. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.8862-8871.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Agger K, Cloos PA, Christensen J, Pasini D, Rose S, Rappsilber J, Issaeva I, Canaani E, Salcini AE, Helin K. UTX and JMJD3 are histone H3K27 demethylases involved in HOX gene regulation and development. Nature. 2007;449:731–734. doi: 10.1038/nature06145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gillespie RF, Gudas LJ. Retinoid regulated association of transcriptional co-regulators and the polycomb group protein SUZ12 with the retinoic acid response elements of Hoxa1, RARbeta(2), and Cyp26A1 in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:298–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kashyap V, Gudas LJ. Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms distinguish retinoic acid-mediated transcriptional responses in stem cells and fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14534–14548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Azuara V, Perry P, Sauer S, Spivakov M, Jorgensen HF, John RM, Gouti M, Casanova M, Warnes G, Merkenschlager M, Fisher AG. Chromatin signatures of pluripotent cell lines. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:532–538. doi: 10.1038/ncb1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, Jaenisch R, Wagschal A, Feil R, Schreiber SL, Lander ES. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McDonald OG, Wamhoff BR, Hoofnagle MH, Owens GK. Control of SRF binding to CArG box chromatin regulates smooth muscle gene expression in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:36–48. doi: 10.1172/JCI26505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Z, Wang DZ, Pipes GC, Olson EN. Myocardin is a master regulator of smooth muscle gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7129–7134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232341100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Illi B, Scopece A, Nanni S, Farsetti A, Morgante L, Biglioli P, Capogrossi MC, Gaetano C. Epigenetic histone modification and cardiovascular lineage programming in mouse embryonic stem cells exposed to laminar shear stress. Circ Res. 2005;96:501–508. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000159181.06379.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Spin JM, Quertermous T, Tsao PS. Chromatin remodeling pathways in smooth muscle cell differentiation, and evidence for an integral role for p300. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zampetaki A, Zeng L, Xiao Q, Margariti A, Hu Y, Xu Q. Lacking cytokine production in ES cells and ES-cell-derived vascular cells stimulated by TNF-alpha is rescued by HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1226–1238. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00152.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Margariti A, Xiao Q, Zampetaki A, Zhang Z, Li H, Martin D, Hu Y, Zeng L, Xu Q. Splicing of HDAC7 modulates the SRF-myocardin complex during stem-cell differentiation towards smooth muscle cells. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:460–470. doi: 10.1242/jcs.034850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoshida T, Gan Q, Owens GK. Kruppel-like factor 4, Elk-1, and histone deacetylases cooperatively suppress smooth muscle cell differentiation markers in response to oxidized phospholipids. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1175–1182. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00288.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cao D, Wang Z, Zhang CL, Oh J, Xing W, Li S, Richardson JA, Wang DZ, Olson EN. Modulation of smooth muscle gene expression by association of histone acetyltransferases and deacetylases with myocardin. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:364–376. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.364-376.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dressel U, Bailey PJ, Wang SC, Downes M, Evans RM, Muscat GE. A dynamic role for HDAC7 in MEF2-mediated muscle differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17007–17013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fuchs E, Tumbar T, Guasch G. Socializing with the neighbors: stem cells and their niche. Cell. 2004;116:769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Walker MR, Patel KK, Stappenbeck TS. The stem cell niche. J Pathol. 2009;217:169–180. doi: 10.1002/path.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Poschl E, Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Brachvogel B, Saito K, Ninomiya Y, Mayer U. Collagen IV is essential for basement membrane stability but dispensable for initiation of its assembly during early development. Development. 2004;131:1619–1628. doi: 10.1242/dev.01037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Behonick DJ, Werb Z. A bit of give and take: the relationship between the extracellular matrix and the developing chondrocyte. Mech Dev. 2003;120:1327–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen SS, Revoltella RP, Papini S, Michelini M, Fitzgerald W, Zimmerberg J, Margolis L. Multilineage differentiation of rhesus monkey embryonic stem cells in three-dimensional culture systems. Stem Cells. 2003;21:281–295. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-3-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hu J, Sun X, Ma H, Xie C, Chen YE, Ma PX. Porous nanofibrous PLLA scaffolds for vascular tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7971–7977. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sone M, Itoh H, Yamahara K, Yamashita JK, Yurugi-Kobayashi T, Nonoguchi A, Suzuki Y, Chao TH, Sawada N, Fukunaga Y, Miyashita K, Park K, Oyamada N, Taura D, Tamura N, Kondo Y, Nito S, Suemori H, Nakatsuji N, Nishikawa S, Nakao K. Pathway for differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to vascular cell components and their potential for vascular regeneration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2127–2134. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.143149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rana TM. Illuminating the silence: understanding the structure and function of small RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:23–36. doi: 10.1038/nrm2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schickel R, Boyerinas B, Park SM, Peter ME. MicroRNAs: key players in the immune system, differentiation, tumorigenesis and cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27:5959–5974. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466:835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, Bartel DP, Linsley PS, Johnson JM. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;433:769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hutvagner G, Zamore PD. A microRNA in a multiple-turnover RNAi enzyme complex. Science. 2002;297:2056–2060. doi: 10.1126/science.1073827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cheng Y, Liu X, Yang J, Lin Y, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Deitch EA, Huo Y, Delphin ES, Zhang C. MicroRNA-145, a novel smooth muscle cell phenotypic marker and modulator, controls vascular neointimal lesion formation. Circ Res. 2009;105:158–166. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cordes KR, Sheehy NT, White MP, Berry EC, Morton SU, Muth AN, Lee TH, Miano JM, Ivey KN, Srivastava D. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature. 2009;460:705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature08195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Boettger T, Beetz N, Kostin S, Schneider J, Kruger M, Hein L, Braun T. Acquisition of the contractile phenotype by murine arterial smooth muscle cells depends on the Mir143/145 gene cluster. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2634–2647. doi: 10.1172/JCI38864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Elia L, Quintavalle M, Zhang J, Contu R, Cossu L, Latronico MV, Peterson KL, Indolfi C, Catalucci D, Chen J, Courtneidge SA, Condorelli G. The knockout of miR-143 and -145 alters smooth muscle cell maintenance and vascular homeostasis in mice: correlates with human disease. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1590–1598. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xin M, Small EM, Sutherland LB, Qi X, McAnally J, Plato CF, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. MicroRNAs miR-143 and miR-145 modulate cytoskeletal dynamics and responsiveness of smooth muscle cells to injury. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2166–2178. doi: 10.1101/gad.1842409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Albinsson S, Suarez Y, Skoura A, Offermanns S, Miano JM, Sessa WC. MicroRNAs are necessary for vascular smooth muscle growth, differentiation, and function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1118–1126. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.200873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jiang X, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest. Development. 2000;127:1607–1616. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nakamura T, Colbert MC, Robbins J. Neural crest cells retain multipotential characteristics in the developing valves and label the cardiac conduction system. Circ Res. 2006;98:1547–1554. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000227505.19472.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mikawa T, Fischman DA. Retroviral analysis of cardiac morphogenesis: discontinuous formation of coronary vessels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:9504–9508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wilm B, Ipenberg A, Hastie ND, Burch JB, Bader DM. The serosal mesothelium is a major source of smooth muscle cells of the gut vasculature. Development. 2005;132:5317–5328. doi: 10.1242/dev.02141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maeda J, Yamagishi H, McAnally J, Yamagishi C, Srivastava D. Tbx1 is regulated by forkhead proteins in the secondary heart field. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:701–710. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Waldo KL, Hutson MR, Ward CC, Zdanowicz M, Stadt HA, Kumiski D, Abu-Issa R, Kirby ML. Secondary heart field contributes myocardium and smooth muscle to the arterial pole of the developing heart. Dev Biol. 2005;281:78–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Esner M, Meilhac SM, Relaix F, Nicolas JF, Cossu G, Buckingham ME. Smooth muscle of the dorsal aorta shares a common clonal origin with skeletal muscle of the myotome. Development. 2006;133:737–749. doi: 10.1242/dev.02226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pouget C, Gautier R, Teillet MA, Jaffredo T. Somite-derived cells replace ventral aortic hemangioblasts and provide aortic smooth muscle cells of the trunk. Development. 2006;133:1013–1022. doi: 10.1242/dev.02269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]