Abstract

Older age is considered a poor prognostic factor in acute liver failure (ALF) and may still be considered a relative contraindication for liver transplantation for ALF. We aimed to evaluate the impact of older age, defined as age ≥ 60 years, on outcomes in patients with ALF. One thousand one hundred twenty-six consecutive prospective patients from the US Acute Liver Failure Study Group registry were studied. The median age was 38 years (range, 15–81 years). One thousand sixteen patients (90.2%) were younger than 60 years (group 1), and 499 (49.1%) of these had acetaminophen-induced ALF; this rate of acetaminophen-induced ALF was significantly higher than that in patients ≥ 60 years (group 2; n = 110; 23.6% with acetaminophen-induced ALF, P < 0.001). The overall survival rate was 72.7% in group 1 and 60.0% in group 2 (not significant) for acetaminophen patients and 67.9% in group 1 and 48.2% in group 2 for non-acetaminophen patients (P < 0.001). The spontaneous survival rate (ie, survival without liver transplantation) was 64.9% in group 1 and 60.0% in group 2 (not significant) for acetaminophen patients and 30.8% in group 1 and 24.7% in group 2 for non-acetaminophen patients (P = 0.27). Age was not a significant predictor of spontaneous survival in multiple logistic regression analyses. Group 2 patients were listed for liver transplantation significantly less than group 1 patients. Age was listed as a contraindication for transplantation in 5 patients. In conclusion, in contrast to previous studies, we have demonstrated a relatively good spontaneous survival rate for older patients with ALF when it is corrected for etiology. However, overall survival was better for younger non-acetaminophen patients. Fewer older patients were listed for transplantation.

Acute liver failure (ALF) is an extremely severe medical entity characterized by coagulopathy, usually widespread hepatic necrosis, hepatic encephalopathy, and often multiorgan failure in a previously healthy individual.1–6 The prognosis of ALF was until recently very dismal, with survival being the exception to the rule, but it has improved considerably over the past few decades.7 Still, mortality is approximately 30% to 40%, and another 20% to 25% need liver transplantation; this means that only 40% to 45% of ALF patients survive spontaneously (ie, without liver transplantation).3,8,9

Older age is believed to be associated with a poor prognosis. Indeed, age greater than 40 years is one of the factors included in the most widely used model for liver transplantation, the King’s College Hospital criteria.10 Studies from India have revealed age greater than 50 years to be associated with an increased risk of death.11,12 However, initial (retrospective) reports from our group suggested that age does not seem to affect outcome.7 With older age, a decline in hepatic volume and hepatic blood flow occurs13–15; however, it remains unclear if hepatic function also declines.13 Fibrinogen levels and albumin synthesis seem to be normal even in very old individuals.16

Several studies have reported age greater than 60 years as a factor for adverse outcomes of liver transplantation.17–20 In this study, we aimed to evaluate the impact of older age, defined as age greater than or equal to 60 years, on outcomes of ALF.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

One thousand one hundred twenty-six patients with ALF who were enrolled prospectively by the US Acute Liver Failure Study Group8 between 1998 and 2007 were studied. The group included 774 women (68.7%). The criteria for admission to the study were coagulopathy (international normalized ratio ≥ 1.5) and the presence of any degree of hepatic encephalopathy in the absence of evident chronic liver disease. After informed consent was obtained from the next of kin, detailed prospective clinical and laboratory data were entered in an anonymous fashion into case report forms upon admission to the study and 3 weeks later or at the time of death or liver transplantation. At the beginning of the study, we established standard criteria for all etiologic groups that were used by site investigators to determine the diagnosis for each patient. To confirm cases of acetaminophen toxicity leading to ALF, investigators used a history of ingestion of doses exceeding the package labeling (>4 g/24 hours) within 7 days of presentation (in most cases, the quantities greatly exceeded this value) combined with the detection of acetaminophen in the plasma of a patient meeting other qualifications for ALF and the finding of characteristic alanine aminotransferase levels ≥ 3500 IU/L. Most patients met at least 2 of these 3 criteria.21

Statistics

Data are presented as medians (range). Comparisons between groups were made with the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. The chi-square test was used to compare rates between groups, and linear regression analysis was used to evaluate trends over time. Multiple regression analyses were performed to analyze the independent impact of age on prognosis. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

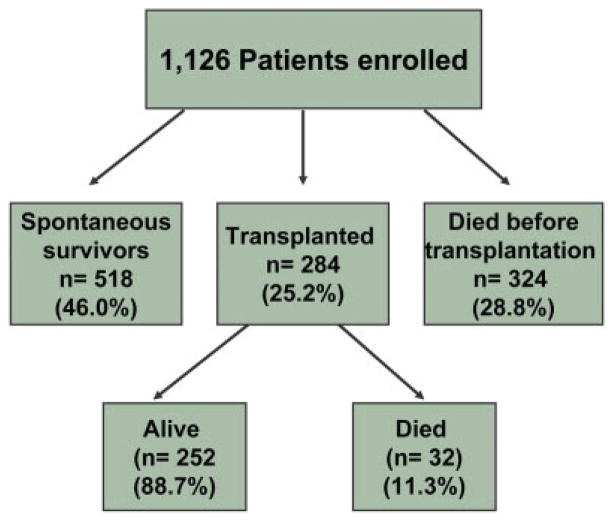

Figure 1 shows the overall outcomes for all patients included in the study. The spontaneous (ie, transplantation-free) survival rate, the liver transplantation rate, and the overall survival rate were 46.0%, 25.2%, and 68.4%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Overall outcome for all acute liver failure patients.

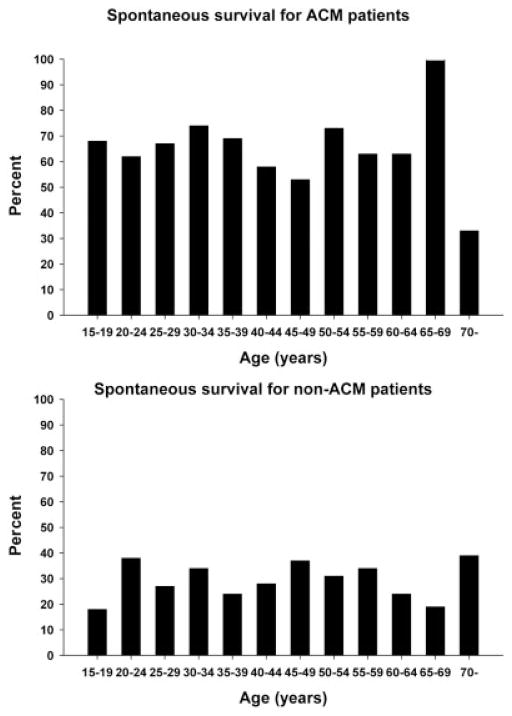

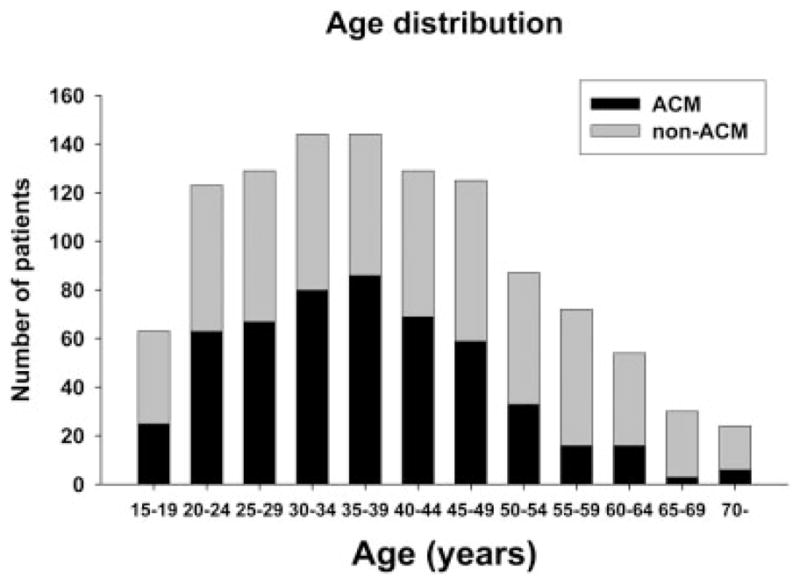

Figure 2 shows the age distribution of the patients. The median age was 38 years (range, 15–81 years). One thousand sixteen patients (90.2%) were younger than 60 years and composed group 1. The 110 patients ≥ 60 years composed group 2. Four hundred ninety-nine patients in group 1 (49.1%) had acetaminophen-induced ALF; this rate of acetaminophen-induced ALF was significantly higher than that in group 2 (22.7%, P < 0.001). Older patients had lower aminotransferases on admission and apparently lower spontaneous survival rates in comparison with younger patients (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Age distribution for all patients. Abbreviation: ACM, acetaminophen.

TABLE 1.

Overall Comparison of Younger and Older Patients

| <60 Years (n = 1016) | ≥60 Years (n = 110) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 700 (68.9%) | 74 (67.3%) | NS |

| Acetaminophen | 499 (49.1%) | 25 (22.7%) | <0.001 |

| Symptom duration (days) | 4 (0–186) | 7 (0–90) | NS |

| HE coma grade III/IV | 648 (63.8%) | 78 (70.9%) | NS |

| INR (AU) | 2.7 (1.5–44.4) | 2.4 (1.5–18) | NS |

| ALT (U/L) | 2,111 (3–26,600) | 1,223 (23–10,956) | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 7.3 (0.3–63.3) | 10.1 (0.2–43.5) | NS |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.7 (0.1–74.8) | 1.7 (0.3–10.7) | NS |

| Liver Tx | 259 (25.5%) | 25 (22.7%) | NS |

| Survival after Tx | 232 (89.6%) | 20 (80.0%) | NS |

| Spontaneous survival | 482 (47.4%) | 36 (32.7%) | 0.004 |

| Overall survival | 714 (70.3%) | 56 (50.9%) | <0.001 |

NOTE: Biochemistry values were recorded on admission to study. Values are given as numbers (%) or medians (range).

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; INR, international normalized ratio; NS, not significant; Tx, transplantation.

For acetaminophen patients, groups 1 and 2 are compared in Table 2. There was a tendency toward higher encephalopathy grades in group 2. Fewer patients in group 2 were listed for transplantation. The gender distribution, symptom duration, liver transplantation rate, biochemical markers (except aminotransferates, and spontaneous survival rates did not differ between the 2 age groups. Figure 3 (upper panel) further shows the spontaneous survival rate, and Fig. 4 (upper panel) shows the liver transplantation rate for all age groups with an acetaminophen etiology.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Younger and Older Patients with an Acetaminophen Etiology (n = 524)

| <60 Years (n = 499) | ≥60 Years (n = 25) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 376 (75.3%) | 20 (80%) | NS |

| Symptom duration (days) | 2 (0–6) | 2 (0–6) | NS |

| HE coma grade III/IV | 324 (64.9%) | 21 (84%) | NS |

| INR (AU) | 2.8 (1.5–44.4) | 2.3 (1.5–6.7) | NS |

| ALT (U/L) | 4091 (136–26,600) | 3342 (104–7861) | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 4.6 (0.3–48.2) | 4.0 (0.2–21.4) | NS |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.0 (0.1–10.5) | 1.4 (0.5–10.7) | NS |

| Listed for Tx | 137 (27.5%) | 2 (8%) | 0.04 |

| Contraindications for Tx | 147 (29.5%) | 8 (32%) | NS |

| Liver Tx | 48 (9.6%) | 0 (0%) | NS |

| Survival after Tx | 40 (83.3%) | NA | NA |

| Spontaneous survival | 324 (64.9%) | 15 (60%) | NS |

| Overall survival | 363 (72.7%) | 15 (60%) | NS |

NOTE: Biochemistry values were recorded on admission to study. Values are given as numbers (%) or medians (range).

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; INR, international normalized ratio; NA, not available; NS, not significant; Tx, transplantation.

Figure 3.

Spontaneous survival rates for patients with an ACM etiology (upper panel) or a non-ACM (lower panel) etiology as a function of age. With linear regression analysis, no trends were found. Abbreviation: ACM, acetaminophen.

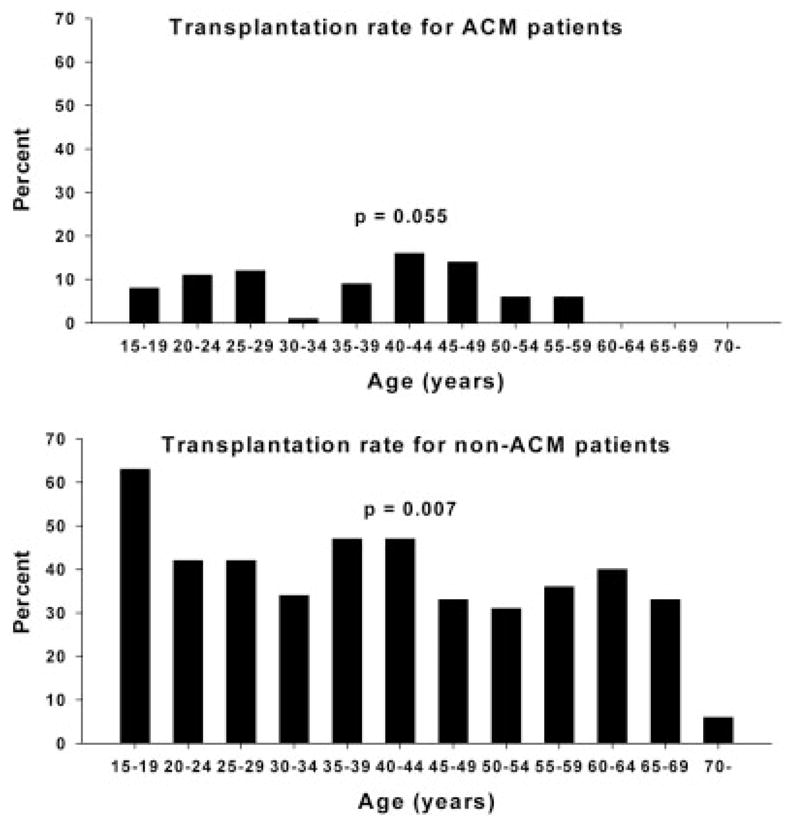

Figure 4.

Transplantation rates for patients with an ACM etiology (upper panel) or a non-ACM etiology as a function of age. With linear regression analysis, a decrease in transplantation was observed with increasing age. Abbreviation: ACM, acetaminophen.

Table 3 compares groups 1 and 2 for non-acetaminophen patients. The non-acetaminophen group (n = 602) consisted of those with drug-induced liver injury (n = 127; 21.1%), hepatitis B (n = 82; 13.6%), autoimmune hepatitis (n = 60; 10.0%), shock liver (n = 47; 7.8%), hepatitis A (n = 31; 5.1%), Wilson’s disease (n = 18; 3.0%), Budd-Chiari syndrome (n = 11; 1.8%), an indeterminate etiology (n = 158; 26.2%), and various other etiologies (n = 68; 11.3%). Pregnancy-related ALF, Budd-Chiari syndrome, and Wilson’s disease were not observed in the older age group, and autoimmune hepatitis was less frequent in the younger age group (8.7% versus 17.6%, respectively, P = 0.026). Fewer patients were listed for transplantation in group 2, and more patients had contraindications for transplantation in this group, including 5 patients for whom old age was listed as a cause for contraindication. These 5 patients were older than 70 years of age. The gender distribution, hepatic coma grade, symptom duration, biochemical markers, and spontaneous survival did not differ between the groups, whereas there was a tendency toward a lower transplantation rate in group 2. Spontaneous survival rates did not differ for age groups, whereas transplantation rates decreased with older age according to linear regression analysis (Figs. 3 and 4, lower panels).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of Younger and Older Patients with a Non-Acetaminophen Etiology (n = 602)

| >60 Years (n = 517) | ≥60 Years (n = 85) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 324 (62.7%) | 54 (63.5%) | NS |

| Symptom duration (days) | 12 (0–186) | 13 (0–117) | NS |

| HE coma grade III/IV | 341 (66.9%) | 56 (65.9%) | NS |

| INR (AU) | 2.6 (1.5–26.1) | 2.5 (1.5–18) | NS |

| ALT (U/L) | 839 (3–13,100) | 758 (23–10,956) | NS |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 19.3 (0.7–63.3) | 14.7 (0.8–43.5) | NS |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.4 (0.1–74.8) | 2.0 (0.3–8.8) | NS |

| Listed for Tx | 300 (58%) | 38 (44.7%) | 0.03 |

| Contraindications for Tx | 95 (18.4%) | 25 (29.4%) | 0.03 |

| Liver Tx | 211 (40.8%) | 25 (29.4%) | 0.058 |

| Survival after Tx | 192 (91.0%) | 20 (80.0%) | NS |

| Spontaneous survival | 159 (30.8%) | 21 (24.7%) | NS |

| Overall survival | 351 (67.9%) | 41 (48.2%) | <0.001 |

NOTE: Biochemistry values were recorded on admission to study. Values are given as numbers (%) or medians (range).

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; INR, international normalized ratio; NS, not significant; Tx, transplantation.

Other contraindications for liver transplantation, besides age, included comorbidities, the medical condition of the patient (eg, uncontrollable infection, multi-organ failure, or severe intracranial hypertension), psychiatric disorders, chronic alcohol use, repeated overdoses, and malignancy and did not differ between acetaminophen and non-acetaminophen patients.

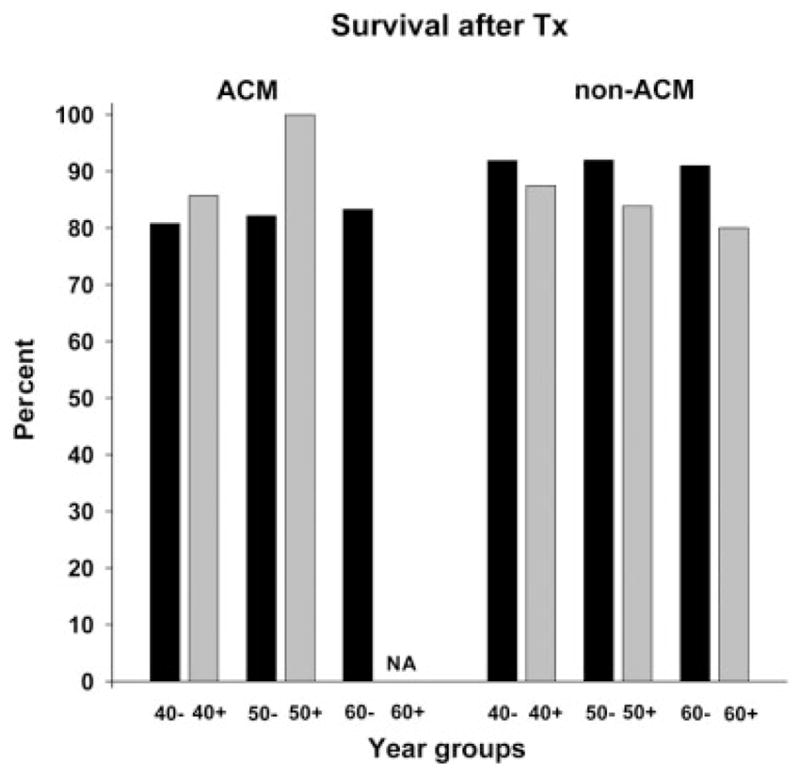

Survival after liver transplantation was not age-dependent (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Survival after transplantation for 48 patients with ACM-induced acute liver failure and for 236 patients with a non-ACM etiology according to age. No significant differences were found. Abbreviations: ACM, acetaminophen; NA, not available; Tx, transplantation.

Age was not a significant predictor of spontaneous survival in multiple logistic regression analyses of outcome for the acetaminophen and non-acetaminophen subgroups with the following variables: age, admission or maximum international normalized ratio, symptom duration, admission bilirubin, creatinine, phosphate, magnesium, acidosis, and hepatic encephalopathy grade (I/II versus III/IV). When transplanted patients were excluded from the analysis, old age was an independent risk factor for nonsurvival in the non-acetaminophen subgroup (P = 0.018), whereas no impact of age was found in the acetaminophen group.

Age > 40 years is a significant risk factor for prognosis in the King’s College Hospital criteria10; therefore, we analyzed outcome with this cutoff level. There were more acetaminophen patients in the group younger than 40 years (n = 322; 53.4%) versus the group of patients 40 years old or older (n = 202; 38.6%, P < 0.001). In the acetaminophen group, the spontaneous survival rate was higher in the younger group than in the older group (68.0% versus 58.9%, respectively, P = 0.043), whereas overall survival and transplantation rates did not differ between the 2 groups. In the non-acetaminophen group, the overall survival was higher in the younger group than in the older group (70.1% versus 60.7%, respectively, P = 0.026). Also, the transplantation rate was higher in the younger group than in the older group (44.1% versus 34.9%, respectively, P = 0.026), whereas the spontaneous survival rate did not differ in the 2 groups.

We previously reported rises in alpha-fetoprotein levels as a sign of hepatic regeneration,22 and we analyzed these data again with respect to age; among nonsurvivors (or transplanted) older than 60 years, 6 of 13 (46%) patients had rising alpha-fetoprotein levels between hospital days 1 and 3 versus only 7 of 51 (13%) patients younger than 60 years (P = 0.018). Among spontaneous survivors, the proportion of patients with alpha-fetoprotein rise did not differ between older and younger patients (57% and 73%, respectively; not significant).

DISCUSSION

The present study has focused on the impact of older age on outcomes of ALF. Overall and spontaneous survival was greater in the younger age group (Table 1); however, this apparently better spontaneous survival for younger patients completely disappeared when we analyzed patients with acetaminophen and non-acetaminophen etiologies separately. Acetaminophen-induced ALF is known to carry a much better prognosis than non–acetaminophen-induced ALF.7,8 Thus, the younger group had more patients with a favorable etiology than the older group. Multiple regression analyses confirmed that age was not an independent risk factor for spontaneous survival, in contrast to findings of previous studies.10,12 Only when excluding transplanted patients did we observe age to be an independent risk factor for non-acetaminophen patients (among whom overall survival was better in the younger group). However, transplanted patients accounted for 30% to 40% of non-acetaminophen patients, and to exclude all these patients with a presumed poor prognosis is not warranted. Also, it should be considered that the relatively small number of older patients, especially in the acetaminophen group, increases the risk of a type II error in the interpretation of the data.

Several prognostic models of outcome of ALF include age as an important risk factor. The most widely used prognostic model, the King’s College Hospital criteria,10 includes age greater than 40 years (or less than 10 years) as an adverse marker of outcome for patients with a non-acetaminophen etiology. Our study confirms a better overall survival for non-acetaminophen patients younger than 40 years, whereas spontaneous survival did not differ between patients younger or older than 40 years. Interestingly, we observed slightly better spontaneous survival in the acetaminophen group among patients younger than 40 years, whereas overall survival was not improved for the younger patient group. Two studies from India have identified age greater than 50 years as a poor prognostic marker.11,12 Also, age greater than 40 years was an independent risk factor for the development of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with acetaminophen overdose in a study from Copenhagen,23 even when corrections were made for later presentation and larger alcohol consumption in the old age group. We cannot explain the differences that we observed with respect to other reports as a difference in patient selection because the aforementioned hospitals and those represented in this study are all tertiary care centers. However, it is possible that less frequent consideration of older individuals for grafting in the United States might limit their initial referral for transplantation. Limited patient referral for patients over 60 years old could cause a selection bias that favors unusually healthy older patients. However, we are not aware of any such differences between the United States and Europe in this regard. The apparent decline in survival for acetaminophen patients over 70 years old may be a real finding or may simply reflect the small sample size in this group (Fig. 3).

We observed that with older age, fewer patients were listed for liver transplantation and fewer underwent transplantation. In the acetaminophen subgroup, no patient older than 60 years was listed, despite the same proportion of contraindications to transplantation as that in patients younger than 60 years. Fewer older patients were also transplanted in the non-acetaminophen subgroup, but in this group, more contraindications to transplantation were met. In our study, survival after transplantation was not lower in older patients (Tables 2 and 3), in contrast to the study of Barshes et al.,24 who found that age greater than 50 years was one of the risk factors for poorer survival following emergency transplantation in a large number of patients registered in the United Network for Organ Sharing database. However, these data were collected between 1988 and 2003, and the likelihood of survival and the overall medical treatment employed for ALF have improved considerably since the beginning of that period.10 A recent British single-center study describes age greater than 45 years as a risk factor for nonsurvival following transplantation for the period of 1994–200425; however, it is worth noting that survival improved considerably in the last half of the observation period.25 The majority of patients in our study were enrolled in the current decade, and this suggests that a comparison with the aforementioned studies is likely to be biased.

Over the past decade, liver transplantation for all causes (not ALF only) for older patients appears to have been increasing in frequency.20 Some studies have reported worse outcome, including lower survival and more frequent development of malignancies, for the elderly,17–19 whereas other studies have reported good results in this age group, even for patients in their seventies.26 A recent British study on liver transplantation found that survival was not decreased for patients older than 60 years or even 65 years.27 This was true for survival at 30 days, 1 year, and 5 years after transplantation. We suggest that transplantation should be considered in older patients in the absence of other contraindications.

It is still not fully elucidated how the liver is affected by increasing age.13,28 In fact, older donor age per se does not appear to adversely affect recipient liver transplantation outcome.29,30 Many hepatic functions, including protein synthesis, remain intact even at a very old age.16 However, liver volume and hepatic blood flow decrease,14,31 and hepatocyte regeneration following partial hepatectomy is reduced considerably in older mice versus younger mice.32,33 Also, the hepatic metabolism of foreign compounds, as judged by the activity of the cytochrome P450 3A system,15,34 and the galactose elimination capacity35 seem to decrease with older age. The hepatocyte morphology changes with older age toward more dense bodies and lipofuscin; however, the importance of these findings remains to be clarified.36 In all, the changes in the liver with aging are not dramatic, and this probably explains the apparently satisfactory recovery from illness that we observed in older patients with ALF. Further support for the hypothesis that hepatic regeneration is preserved in the elderly was found in our data regarding alpha-fetoprotein. Rising alpha-fetoprotein levels were observed in the same proportion of older and younger patients. However, it should also be noted that the lower amino-transferase levels in the elderly (Tables 2 and 3) may reflect a lower hepatic volume in this group.

Despite possible biases, this study indicates that the prognosis for spontaneous survival among older patients is not inferior to that for younger patients. We suspect that hepatocyte regeneration remains, for the most part, intact in older patients with ALF. Consideration should be given to liver transplantation in older patients with ALF in the absence of other contraindications.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a National Institutes of Health grant (DK U-01 58369) provided by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases for the Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Additional funding was provided by the Tips Fund of the Northwestern Medical Foundation and the Jeanne Roberts and Rollin and Mary Ella King Funds of the Southwestern Medical Foundation.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the members of the Acute Liver Failure Study Group (1998–2006). The members and institutions participating in the Acute Liver Failure Study Group (1998–2006) were as follows: W. M. Lee, M.D. (principal investigator), George A. Ostapowicz, M.D., Frank V. Schiødt, M.D., and Julie Polson, M.D., University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX; Anne M. Larson, M.D., University of Washington, Seattle, WA; Timothy Davern, M.D., University of California, San Francisco, CA; Michael Schilsky, M.D., Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY; Timothy McCashland, M.D., University of Nebraska, Omaha, NE; J. Eileen Hay, M.B.B.S., Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN; Natalie Murray, M.D., Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, TX; A. Obaid S. Shaikh, M.D., University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; Andres Blei, M.D., Northwestern University, Chicago, IL; Atif Zaman, M.D., University of Oregon, Portland, OR; Steven H. B. Han, M.D., University of California, Los Angeles, CA; Robert Fontana, M.D., University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI; Brendan McGuire, M.D., University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL; Ray Chung, M.D., Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA; Alastair Smith, M.B., Ch.B., Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC; Robert Brown, M.D., Cornell/Columbia University, New York, NY; Jeffrey Crippin, M.D., Washington University, St. Louis, MO; Edwin Harrison, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ; Adrian Reuben, M.B.B.S., Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC; Santiago Munoz, M.D., Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA; Rajender Reddy, M.D., University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA; R. Todd Stravitz, M.D., Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA; Lorenzo Rossaro, M.D., University of California Davis, Sacramento, CA; Raj Satyanarayana, M.D., Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL; and Tarek Hassanein, M.D., University of California, San Diego, CA. The University of Texas Southwestern Administrative Group included Grace Samuel, Ezmina Lalani, Carla Pezzia, and Corron Sanders, Ph.D., and the Statistics and Data Management Group included Joan Reisch, Ph.D., Linda Hynan, Ph.D., Janet P. Smith, Joe W. Webster, and Mechelle Murray. The authors further acknowledge all the coordinators from the study sites as well as the patients and families that participated in this study.

Abbreviations

- ACM

acetaminophen

- ALF

acute liver failure

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- INR

international normalized ratio

- NA

not available

- NS

not significant

- Tx

transplantation

Footnotes

This article was presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Boston, MA, November 2–6, 2007, as an oral presentation (abstract 92).

References

- 1.Trey C, Davidson CS. The management of fulminant hepatic failure. In: Popper H, Schaffner F, editors. Progress in Liver Diseases. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; 1970. pp. 282–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee WM, Schiødt FV. Fulminant hepatic failure. In: Schiff ER, Sorrell MF, Maddrey WC, editors. Schiff’s Diseases of the Liver. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. pp. 879–895. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee WM, Squires RH, Jr, Nyberg SL, Doo E, Hoofnagle JH. Acute liver failure: summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2008;47:1401–1415. doi: 10.1002/hep.22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostapowicz G, Lee WM. Acute hepatic failure: a Western perspective. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:480–488. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiødt FV, Lee WM. Fulminant liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:331–349. vi. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(03)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutherford A, Chung RT. Acute liver failure: mechanisms of hepatocyte injury and regeneration. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:167–174. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1073116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiødt FV, Atillasoy E, Shakil AO, Schiff ER, Caldwell C, Kowdley KV, et al. Etiology and outcome for 295 patients with acute liver failure in the United States. Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:29–34. doi: 10.1002/lt.500050102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiødt FV, Larson A, Davern TJ, Han SH, et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947–954. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polson J. Assessment of prognosis in acute liver failure. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:218–225. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1073121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Grady JG, Alexander GJ, Hayllar KM, Williams R. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:439–445. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhiman RK, Jain S, Maheshwari U, Bhalla A, Sharma N, Ahluwalia J, et al. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure: an assessment of the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) and King’s College Hospital criteria. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:814–821. doi: 10.1002/lt.21050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhiman RK, Seth AK, Jain S, Chawla YK, Dilawari JB. Prognostic evaluation of early indicators in fulminant hepatic failure by multivariate analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1311–1316. doi: 10.1023/a:1018876328561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeeh J, Platt D. The aging liver: structural and functional changes and their consequences for drug treatment in old age. Gerontology. 2002;48:121–127. doi: 10.1159/000052829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wynne HA, Cope LH, Mutch E, Rawlins MD, Woodhouse KW, James OF. The effect of age upon liver volume and apparent liver blood flow in healthy man. Hepatology. 1989;9:297–301. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iber FL, Murphy PA, Connor ES. Age-related changes in the gastrointestinal system. Effects on drug therapy Drugs Aging. 1994;5:34–48. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199405010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu A, Nair KS. Age effect on fibrinogen and albumin synthesis in humans. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(pt 1):E1023–E1030. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.6.E1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins BH, Pirsch JD, Becker YT, Hanaway MJ, Van der Werf WJ, D’Alessandro AM, et al. Long-term results of liver transplantation in older patients 60 years of age and older. Transplantation. 2000;70:780–783. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200009150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy MF, Somasundar PS, Jennings LW, Jung GJ, Molmenti EP, Fasola CG, et al. The elderly liver transplant recipient: a call for caution. Ann Surg. 2001;233:107–113. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200101000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrero JI, Lucena JF, Quiroga J, Sangro B, Pardo F, Rotellar F, et al. Liver transplant recipients older than 60 years have lower survival and higher incidence of malignancy. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1407–1412. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2003.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keswani RN, Ahmed A, Keeffe EB. Older age and liver transplantation: a review. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:957–967. doi: 10.1002/lt.20155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, Davern TJ, Lalani E, Hynan LS, et al. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2005;42:1364–1372. doi: 10.1002/hep.20948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiødt FV, Ostapowicz G, Murray N, Satyanarana R, Zaman A, Munoz S, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein and prognosis in acute liver failure. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1776–1781. doi: 10.1002/lt.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt LE. Age and paracetamol self-poisoning. Gut. 2005;54:686–690. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.054619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barshes NR, Lee TC, Balkrishnan R, Karpen SJ, Carter BA, Goss JA. Risk stratification of adult patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation for fulminant hepatic failure. Transplantation. 2006;81:195–201. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000188149.90975.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernal W, Cross TJ, Auzinger G, Sizer E, Heneghan MA, Bowles M, et al. Outcome after wait-listing for emergency liver transplantation in acute liver failure: a single centre experience. J Hepatol. 2009;50:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipshutz GS, Hiatt J, Ghobrial RM, Farmer DG, Martinez MM, Yersiz H, et al. Outcome of liver transplantation in septuagenarians: a single-center experience. Arch Surg. 2007;142:775–781. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.8.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cross TJ, Antoniades CG, Muiesan P, Al Chalabi T, Aluvihare V, Agarwal K, et al. Liver transplantation in patients over 60 and 65 years: an evaluation of long-term outcomes and survival. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1382–1388. doi: 10.1002/lt.21181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmucker DL. Age-related changes in liver structure and function: implications for disease ? Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:650–659. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoofnagle JH, Lombardero M, Zetterman RK, Lake J, Porayko M, Everhart J, et al. Donor age and outcome of liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1996;24:89–96. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson CD, Vachharajani N, Doyle M, Lowell JA, Wellen JR, Shenoy S, et al. Advanced donor age alone does not affect patient or graft survival after liver transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:847–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wakabayashi H, Nishiyama Y, Ushiyama T, Maeba T, Maeta H. Evaluation of the effect of age on functioning hepatocyte mass and liver blood flow using liver scintigraphy in preoperative estimations for surgical patients: comparison with CT volumetry. J Surg Res. 2002;106:246–253. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2002.6462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bucher NL, Swaffield MN. The rate of incorporation of labeled thymidine into the deoxyribonucleic acid of regenerating rat liver in relation to the amount of liver excised. Cancer Res. 1964;24:1611–1625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bucher NL, Swaffield MN, Ditroia JF. The influence of age upon the incorporation of thymidine 2-C14 into the DNA of regenerating rat liver. Cancer Res. 1964;24:509–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cotreau MM, von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ. The influence of age and sex on the clearance of cytochrome P450 3A substrates. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:33–60. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marchesini G, Bua V, Brunori A, Bianchi G, Pisi P, Fabbri A, et al. Galactose elimination capacity and liver volume in aging man. Hepatology. 1988;8:1079–1083. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmucker DL. Hepatocyte fine structure during maturation and senescence. J Electron Microsc Tech. 1990;14:106–125. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1060140205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]