Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Hyperglycemia in patients admitted for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is associated with increased in-hospital mortality. We evaluated the relationship between admitting (nonfasting) blood glucose and in-hospital mortality in patients with and without diabetes mellitus (DM) presenting with ACS in Oman.

Patients and Methods:

Data were analyzed from 1551 consecutive patients admitted to 15 hospitals throughout Oman, with the final diagnosis of ACS during May 8, 2006 to June 6, 2006 and January 29, 2007 to June 29, 2007, as part of Gulf Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Admitting blood glucose was divided into four groups, namely, euglycemia (≤7 mmol/l), mild hyperglycemia (>7-<9 mmol/l), moderate hyperglycemia (≥9-<11 - mmol/l), and severe hyperglycemia (≥11 mmol/l).

Results:

Of all, 38% (n = 584) and 62% (n = 967) of the patients were documented with and without a history of DM, respectively. Nondiabetic patients with severe hyperglycemia were associated with significantly higher in-hospital mortality compared with those with euglycemia (13.1 vs 1.52%; P<0.001), mild hyperglycemia (13.1 vs 3.62%; P = 0.003), and even moderate hyperglycemia (13.1 vs 4.17%; P = 0.034). Even after multivariate adjustment, severe hyperglycemia was still associated with higher in-hospital mortality when compared with both euglycemia (odds ratio [OR], 6.3; P<0.001) and mild hyperglycemia (OR, 3.43; P = 0.011). No significant relationship was noted between admitting blood glucose and in-hospital mortality among diabetic ACS patients even after multivariable adjustment (all P values >0.05).

Conclusion:

Admission hyperglycemia is common in ACS patients from Oman and is associated with higher in-hospital mortality among those patients with previously unreported DM.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome, admission hyperglycemia, diabetes mellitus, hyperglycemia, in-hospital mortality

INTRODUCTION

It is well known that among patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), diabetes mellitus (DM) is associated with worse outcomes and higher mortality rates.[1,2] Hyperglycemia in patients admitted for ACS is associated with increased in-hospital and long-term mortality in both patients with and without DM.[3–6] Furthermore, hyperglycemia at admission in ACS patients is a stronger predictor for in-hospital and long-term mortality in nondiabetic patients.[7–10]

The burden of DM in Gulf countries is highest among all nations (13–18% vs 6–7% global prevalence) and according to International Diabetic Federation, it will double by 2030.[11] Prevalence of DM among ACS patients in Gulf countries is reported to be 40%.[12] Although the prevalence of DM is increasing, DM remains undiagnosed in many patients. There is currently only a scant literature that has explored the relationship between admitting (nonfasting) blood glucose and in-hospital mortality in ACS patients with or without DM in developing countries like Oman or the Gulf region. Hence, we evaluated the association between admitting blood glucose and in-hospital mortality in ACS patients with and without DM in Oman.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

In this analysis, consecutive ACS patients from a prospective registry, Gulf RACE Registry of Acute Coronary Events (RACE), was used. Gulf RACE was a prospective, multinational, multicentre registry of consecutive patients above 18 years of age hospitalized with the final diagnosis of ACS (unstable angina, ST-elevation, and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction) from various hospitals in six Middle Eastern countries.

There were no exclusion criteria. Recruitment in the pilot phase started from May 8, 2006 to June 6, 2006. Enrollment in the next phase of the registry started on January 29, 2007 and continued for 5 months until June 29, 2007. The present study included patients from the registry admitted to 15 hospitals throughout Oman during this period. Methods of multinational Gulf RACE have already been described previously.[12]

Patients presenting with ACS were stratified into the following two groups on the basis of their diabetic history: nondiabetic group and diabetic group. Diabetic group consisted of patients with a known history of type 1 or type 2 DM treated with diet, oral hypoglycemic agents, or insulin. Demographic and other baseline clinical characteristics of the patients along with in-hospital mortality were elicited. Blood for plasma glucose determinations was collected immediately after admission, and analyzed. Admitting blood glucose was divided into four groups, namely, euglycemia (≤7 mmol/l), mild hyperglycemia (>7–<9 mmol/l), moderate hyperglycemia (≥9–<11 mmol/l), and severe hyperglycemia (≥11 mmol/l).

Institutional review board approval was obtained. The treatment for ACS and diabetes were at the discretion of the treating physician.

Statistical analysis

For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages were reported. Differences between groups were analyzed using univariate logistic regression. For continuous variables, mean and standard deviation were reported and analyses were conducted using univariate linear regression. Multivariable adjustment was performed using logistic regression. The dependent variable, in both the nondiabetic and diabetic models, was in-hospital mortality. The main independent variable was blood glucose group, with euglycemia as the reference cohort. Other covariates in the two models included the significant variables in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The results of the logistic models are presented as odds ratio (OR) with the associated 95% confidence interval.

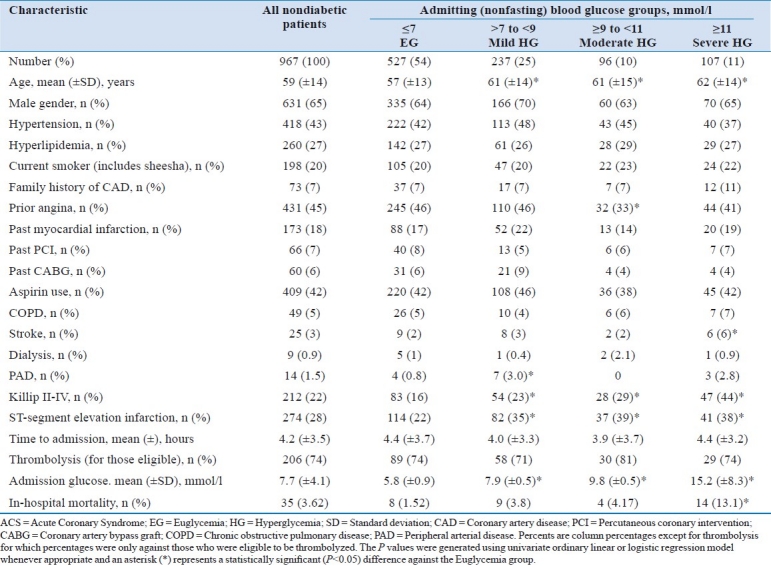

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of ACS patients without documented history of diabetes mellitus

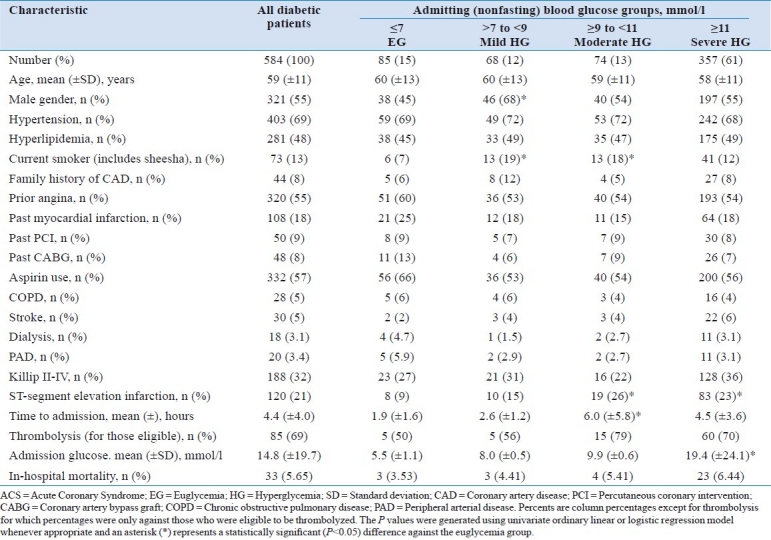

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of ACS patients with documented history of diabetes mellitus

The goodness-of-fit of the logistic models were examined using the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic.[13] This test analyses the actual vs the predicted response; theoretically, the observed and expected counts should be close. On the basis of the χ2 distribution, a Hosmer and Lemeshow statistic with a P value greater than 0.05 is considered a good fit. The discriminatory power of the logistic model was assessed by the area under the receiver operative characteristics (ROC) curve, also known as C-index.[14] A model with perfect discriminative ability has a C-index of 1.0; an index of 0.5 provides no better discrimination than chance. Models with area under the ROC curve of greater than 0.7 were preferred. An a priori two-tailed level of significance was set at the 0.05 level. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 11.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 1583 ACS subjects were recruited from hospitals throughout Oman. However, 32 subjects (2%) were excluded due to missing information. The remaining 1551 subjects represents the sample size for this study. Of all, 38% (n = 584) and 62% (n = 967) of the patients were documented with and without a history of DM, respectively. Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients without DM. A substantial proportion (46%) of ACS patients with elevated admitting blood glucose along with 25% (n = 237) in the mild hyperglycemia group, 10% (n = 96) in the moderate hyperglycemia group, and 11% (n = 107) in the severe hyperglycemia group did not have previously recorded DM. The in-hospital mortality in the diabetic group was slightly, but not significantly, higher when compared with the in-hospital mortality of the nondiabetic cohort (5.65 vs 3.62%; P = 0.058).

Patients without a history of DM

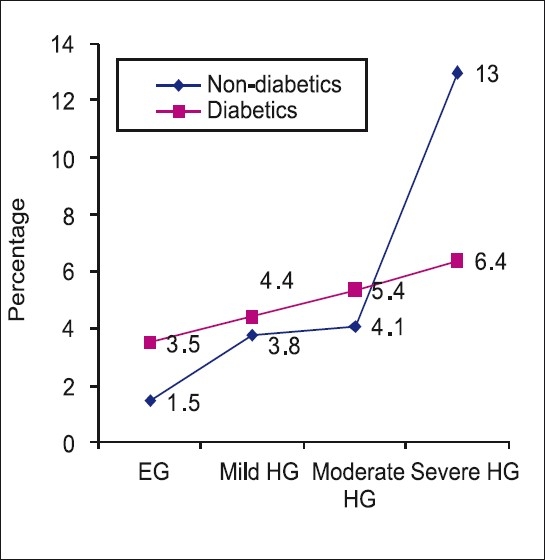

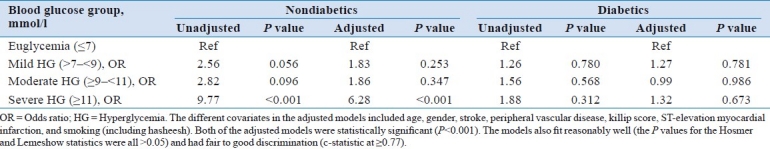

There was a near-linear relationship between admitting (nonfasting) blood glucose levels and in-hospital mortality. Higher admitting blood glucose levels were associated with higher in-hospital mortalities [Figure 1]. Those nondiabetic patients with severe hyperglycemia were associated with significantly higher in-hospital mortality compared with those with euglycemia (13.1 vs 1.52%; P<0.001), mild hyperglycemia (13.1 vs 3.62%; P = 0.003), and even moderate hyperglycemia (13.1 vs 4.17%; P = 0.034). Even after multivariable adjustment, higher admitting blood glucose levels were still associated with higher in-hospital mortality [Table 3]. Specifically, those with severe hyperglycemia were still more likely to be associated with higher in-hospital mortality compared to those with euglycemia (OR, 6.3; P<0.001) or mild hyperglycemia (OR, 3.43; P = 0.011).

Figure 1.

Showing relationship between severity of glycemia and in-hospital mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome. EG = Euglycemia; HG = Hyperglycemia

Table 3.

Relationship between admitting blood glucose and in-hospital mortality stratified by diabetes mellitus using univariate and multivariable logistic regression

Patients with a history of DM

Only 15% (n = 85) had normal blood glucose levels at admission [Table 2]. Majority of the diabetics were not controlled, with 61% (n = 357) having severe hyperglycemia. There was also a slight near-linear relationship between admitting blood glucose levels and in-hospital mortality, though not as steep compared with those without a history of DM [Figure 1]. However, this relationship between admitting blood glucose levels and in-patient mortality was not significant [Table 1]. There were no significant differences in in-hospital mortalities between those with severe hyperglycemia and those with euglycemia (P = 0.312), mild hyperglycemia (P = 0.525), or those with moderate hyperglycemia (P = 0.738). The relationship between admitting blood glucose and in-hospital mortality was still not evident even after multivariable adjustment using logistic regression [Table 3].

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrates that elevated admission glucose levels are associated with increased in-hospital mortality in nondiabetic ACS patients from Oman. This has been noted in other populations as well.[15–18] The prevalence of new-onset hyperglycemia has varied widely from 3 to 71% depending on the definition used.[16] In our study, 46% of the ACS patients with elevated admitting blood glucose did not have previously recorded DM. This number is dangerously high due to the fact that Middle East population already has high prevalence of DM ranging from 13 to 18%, when compared with global prevalence of 6 to 7%.[11] Moreover, in a recent analysis of Gulf RACE from Oman, the prevalence of diabetes was reported to be 36%, along with 66% prevalence of metabolic syndrome.[19] Furthermore, we demonstrated that the more severe the admitting hyperglycemia in nondiabetic patients, the higher the in-hospital mortality. These findings have been noted across the entire range of ACS, including unstable angina, ST-elevation and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction.[3] Those nondiabetic patients with severe hyperglycemia were associated with significantly higher in-hospital mortality compared with those with euglycemia, mild hyperglycemia, and even moderate hyperglycemia, with near-linear relationship being noted between the admission glucose levels and in-hospital mortality. This near-linear relationship between admission blood glucose and in-hospital mortality was not evident in the diabetic group.

This disparity in in-hospital mortality between diabetic and nondiabetic patients with increasing and severe admitting hyperglycemia is not clearly elucidated, even though overall mortality was higher in the diabetic group. Various causes have been postulated to explain this disparity. Secondary to hyperadrenergic state following ACS, stress-related relative insulin deficiency develops leading to stress hyperglycemia.[6] Cardiovascular stress induces release of catecholamines, cortisol, and glucagon, leading to increases in glucose and free fatty acids that enhance hepatic gluconeogenesis, diminish peripheral glucose uptake, and decrease myocardial glucose utilization, all of which may have adverse effects on myocardial energy metabolism and function in the presence of ischemia.[6]

Previous studies suggested that about 65% of nondiabetic patients with ACS have undetected impaired glucose tolerance and undiagnosed DM.[20,21] Beta-cell dysfunction in patients with acute myocardial infarction but without previously known DM has been demonstrated in a study leading to acute hyperglycemia.[22] An ACS may unmask preexisting insulin resistance and pancreatic cell dysfunction. On the basis of this, it is inferred that many nondiabetic patients are in a prediabetic state and an acute coronary event may unmask their diabetic status. Another important reason could be management bias against nondiabetic patients who are less likely to be monitored for their glucose regulation during admission, than in patients with known DM.[6]

Hyperglycemia in ACS causes impaired left ventricular function, increased incidence of the no-reflow phenomenon (a tendency for arrhythmias), enhanced oxidative stress, enhanced thrombin generation, activated platelet aggregation/thrombosis, and activated coagulation factor VII leading to a proinflammatory state with vasoconstriction and endothelial cell dysfunction.[23,24] Also, hyperglycemia may cause dehydration resulting in volume depletion, decreased stroke volume, and low output failure.[6] All of these can increase the risk of reinfarction, heart failure, or death. Recently, it has been demonstrated that hyperglycemia in ACS is associated with reduced clot permeability and susceptibility to lysis in patients with and without a previous history of DM.[25,26] Among other effects, hyperglycemia induces the increase of cytokines, which causes a neutrophil-mediated injury during reperfusion after myocardial ischemia.[27]

Our study has therapeutic implications. In a study from United Kingdom, 64% of nondiabetic ACS patients with admission glucose >11 mmol/l received no glucose-lowering treatment during hospitalization, which significantly increased short- and long-term mortality.[28] The results from our study underscores the need for effective glucose lowering treatment in patients with admission hyperglycemia to prevent mortality. However, more observational and randomized clinical trial data are needed to establish whether target-driven glucose lowering with insulin improves outcomes in hyperglycemic patients with ACS. According to a statement by the American Heart Association, a reasonable initial approach is to consider intensive glucose control in critically ill ACS patients who have significant hyperglycemia on admission (>9.9 mmol/l).[29]

This study included a large number of patients, but still the limitations of a registry-type study apply. Although multivariate adjustments were performed, unmeasured variables may exist that could not have been adjusted. The present analysis includes a subgroup of Gulf RACE patients in whom admission glucose levels were available; patients without available glucose levels may have differed substantially from those included in this analysis, although the number excluded was rather small (n = 32; 2%). Furthermore, the admission blood glucose may represent either random or fasting levels, which may have different outcomes. Finally, in few patients, admission glucose might be falsely elevated due to glucose-containing infusions, or falsely normal due to intravenous insulin administration.

In conclusion, our results confirm that admission hyperglycemia is common in ACS patients from Oman and is associated with higher in-hospital mortality among nondiabetic patients. This group of patients requires specific care involving monitoring and pharmacological intervention. Furthermore, screening of patients in Gulf countries for possible undiagnosed DM may help decrease future risks.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Franklin K, Goldberg RJ, Spencer F, Klein W, Budaj A, Brieger D, et al. Implication of diabetes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1457–63. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.13.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donahoe SM, Stewart GC, McCabe CH, Mohanavelu S, Murphy SA, Cannon CP, et al. Diabetes and mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2007;298:765–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foo K, Cooper J, Deaner A, Knight C, Suliman A, Ranjadayalan K, et al. A single serum glucose measurement predicts adverse outcomes across the whole range of acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 2003;89:512–6. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.5.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gale CP, Kashinath C, Brooksby P. The association between hyperglycemia and elevated troponin levels on mortality in acute coronary syndromes. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2006;3:80–3. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2006.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goyal A, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Nicolau JC, Hochman JS, Weaver WD, et al. Prognostic significance of the change in glucose level in the first 24 h after acute myocardial infarction: results from the CARDINAL study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1289–97. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stranders I, Diamant M, van Gelder RE, Spruijt HJ, Twisk JW, Heine RJ, et al. Admission blood glucose level as risk indicator of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:982–98. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.9.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capes SE, Hunt D, Malmberg K, Gerstein HC. Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview. Lancet. 2000;355:773–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)08415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahab NN, Cowden EA, Pearce NJ, Gardner MJ, Merry H, Cox JL. ICONS Investigators.Is blood glucose an independent predictor of mortality in acute myocardial infarction in the thrombolytic era? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1748–54. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02483-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadjadj S, Coisne D, Mauco G, Ragot S, Duengler F, Sosner P, et al. Prognostic value of admission plasma glucose and HbA in acute myocardial infarction. Diabet Med. 2004;21:305–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosiborod M, Rathore SS, Inzucchi SE, Masoudi FA, Wang Y, Havranek EP, et al. Admission glucose and mortality in elderly patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: implications for patients with and without recognized diabetes. Circulation. 2005;111:3078–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.517839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.IDF Diabetes Atlas. fourth edition. 2009. [Accessed on 2010 March 29]. Available at: http://www.diabetesatlas.org/content/diabetes-and-impaired-glucose-tolerance .

- 12.Zubaid M, Rashed WA, Almahmeed W, Al-Lawati J, Sulaiman K, Al-Motarreb A, et al. Management and outcomes of Middle Eastern patients admitted with acute coronary syndromes in the Gulf Registry of Acute Coronary Events (Gulf RACE) Acta Cardiol. 2009;64:439–46. doi: 10.2143/AC.64.4.2041607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DWJ. A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115:92–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monteiro S, Monteiro P, Gonçalves F, Freitas M, Providência LA. Hyperglycaemia at admission in acute coronary syndrome patients: prognostic value in diabetics and non-diabetics. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:155–9. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32832e19a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angeli F, Verdecchia P, Karthikeyan G, Mazzotta G, Del Pinto M, Repaci S, et al. New-onset hyperglycemia and acute coronary syndrome: a systematic overview and meta-analysis. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2010;6:102–10. doi: 10.2174/157339910790909413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishihara M, Kojima S, Sakamoto T, Kimura K, Kosuge M, Asada Y, et al. Japanese Acute Coronary Syndrome Study (JACSS) Investigators.Comparison of blood glucose values on admission for acute myocardial infarction in patients with versus without diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:769–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosiborod M, Inzucchi SE, Krumholz HM, Xiao L, Jones PG, Fiske S, et al. Glucometrics in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: defining the optimal outcomes-based measure of risk. Circulation. 2008;117:1018–27. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.740498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panduranga P, Sulaiman KJ, Al-Zakwani IS, Al-Lawati JA. Characteristics, management and in-hospital outcomes of diabetic acute coronary syndrome patients in Oman. Saudi Medical Journal. 2010;31:520–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okosieme OE, Peter R, Usman M, Bolusani H, Suruliram P, George L, et al. Can admission and fasting glucose reliably identify undiagnosed diabetes in patients with acute coronary syndrome? Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1955–9. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norhammar A, Tenerz A, Nilsson G, Hamsten A, Efendíc S, Rydén L, et al. Glucose metabolism in patients with acute myocardial infarction and no previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359:2140–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09089-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallander M, Bartnik M, Efendic S, Hamster A, Malmberg K, Öhrvik J, et al. Beta cell dysfunction in patients with acute myocardial infarction but without previously known type 2 diabetes: a report from the GAMI study. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2229–35. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1931-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ceriello A. Acute hyperglycaemia: a “new” risk factor during myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:328–31. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaidyula VR, Boden G, Rao AK. Platelet and monocyte activation by hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in healthy individuals. Platelets. 2006;17:577–85. doi: 10.1080/09537100600760814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Undas A, Szuldrzynski K, Stepien E, Zalewski J, Godlewski J, Pasowicz M, et al. Reduced clot permeability and susceptibility to lysis in patients with acute coronary syndrome: effects of inflammation and oxidative stress. Atherosclerosis. 2007;196:551–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Undas A, Wiek I, Stêpien E, Zmudka K, Tracz W. Hyperglycemia is associated with enhanced thrombin formation, platelet activation, and fibrin clot resistance to lysis in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1590–5. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esposito K, Nappo F, Marfella R, Giugliano G, Giugliano F, Ciotola M, et al. Inflammatory cytokine concentrations are acutely increased by hyperglycemia in humans: role of oxidative stress. Circulation. 2002;106:2067–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034509.14906.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weston C, Walker L, Birkhead J. National Audit of Myocardial Infarction Project, National Institute for Clinical Outcomes Research.Early impact of insulin treatment on mortality for hyperglycaemic patients without known diabetes who present with an acute coronary syndrome. Heart. 2007;93:1542–6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.108696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deedwania P, Kosiborod M, Barrett E, Ceriello A, Isley W, Mazzone T, et al. Hyperglycemia and acute coronary syndrome.A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Diabetes Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2008;117:1610–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]