Abstract

Background:

Heart failure (HF) is a common medical problem with a high impact on public health. Evidence of gender difference in management of HF is scarce. We conducted a retrospective study to evaluate the presence of gender difference in management of HF patients admitted to the tertiary care hospital in the Aseer region/Saudi Arabia.

Patients and Methods:

A chart review was conducted at Aseer Central Hospital (ACH) on consecutive patients admitted with the primary diagnosis of HF between Jun 2007 and May 2009. Data were collected on clinical and management profiles and analyzed for the presence of gender difference in HF management.

Results:

A total of 206 male patients and 94 female patients with HF were reviewed. Ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathy etiologies were significantly higher in male patients (42.7 vs. 28.7%, P < 0.021) and (13.1% vs. 3.2%, P < 0.008), respectively. Renal failure and atrial fibrillation were significantly higher in female patients with HF (20.2 vs., 5.3% P < 0.001) and (20.2 vs. 10.2%, P < 0.018), respectively. Smoking was significantly higher in male patients (11.7 vs. 0%, P < 0.001). Echocardiography was performed equally for both genders and ejection fraction was significantly higher in female patients (38.2 ± 16.9% vs. 30.4 ± 16.6%, P < 0.001). Beta-blockers were prescribed significantly less to female patients (36.2 vs. 57.8%, P < 0.001), while ACE inhibitors and digoxin were prescribed significantly less to male patients (64.1 vs.75.5%, P < 0.049) and (24.8 vs. 36.2%, P < 0.042), respectively.

Conclusion:

Gender differences were detected in clinical presentation and management of HF. Female patients with HF had less ischemic etiology and smoking, but more atrial fibrillation and renal dysfunction. Female patients were under-treated by Beta-blockers while male patients were under-treated by ACE inhibitors and digoxin. Both genders were investigated equally, and female patients had a better ejection fraction.

Keywords: Gender bias, Heart failure, management

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) is a common medical problem, in which the heart fails to meet the peripheral tissue demands at a normal filling pressure.[1] The global prevalence of HF is estimated to be 2.3–3.9% per annum.[2–4] Around 25 million people around the world are suffering from HF, and each year 2 million new cases of HF are diagnosed. It has a high mortality and morbidity rates and an enormous impact on health care system and public health.[5–10] The incidence and prevalence of HF continue to increase likely due to therapeutic improvement in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction and hypertension and also due to increase in the aging population.

Evidence from the literature showed that gender discrepancies in HF management may exist.[11–16] Elderly women make up a greater proportion of HF patients in those over 75 years of age.[7,8] Earlier studies such as Framingham reported better survival among female patients with HF compared to males.[6,9] Other recent trials with accurate assessment of left ventricular function showed contradicting results where female patients with HF had a higher mortality rate.[17] Although gender bias in ischemic heart disease (IHD) management is well studied,[18–29] the evidence of gender bias in HF management is scarce.

The Aseer region (population of 1,200,000) is located in the southwest of Saudi Arabia covering an area of more than 80,000 km2. The region extends from the high mountains of Sarawat (with an altitude of 3200 m above sea level) to the Red Sea. Health service delivery in the Aseer region is provided by a network of 244 primary health care centers, 16 referral hospitals and one tertiary hospital, Aseer Central Hospital (ACH). ACH, with 500 beds, is run by the Ministry of Health and the College of Medicine of King Khalid University (KKU), Abha.

This study was designed to investigate whether gender difference exists in the management of HF patients admitted to ACH, Aseer region/Saudi Arabia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective cohort of all consecutive patients admitted to ACH with the diagnosis of HF during the period from June 2007 to May 2009 were studied. Patients′ data were reviewed and tabulated for both genders. These data including the clinical profile of HF (demographic data, etiologic factors for HF, associated risk factors for HF such as: diabetes, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and renal failure), and echocardiographic features. Data on the management profile of HF using different therapeutic agents were obtained. Data on both genders were collected and compared. Approval of the local medical ethical committee was obtained. Data were analyzed using SPSS software package. Frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, and median were used to present the data. Chi square and the Student “t” were used as tests of significance at the 5% level.

RESULTS

A total of 206 male patients (68.7%) and 94 female patients (31.3%) with the diagnosis of HF were included.

Clinical profile of HF patients

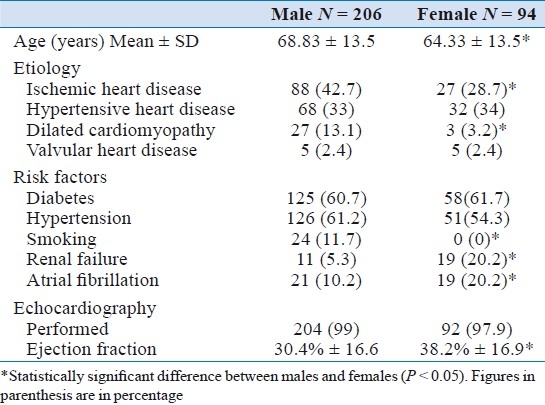

Table 1 showed gender differences in the clinical profile of HF patients. Male patients were significantly older than female patients (68.83 ± 13.5 vs. 64.33 ± 13.5, respectively, P < 0.008).

Table 1.

Gender differences in clinical profile of heart failure patients

As an etiology for heart failure ischemic heart disease and dilated cardiomyopathy were significantly higher in male patients than female patients (42.7 vs. 28.7%, P < 0.021) and (13.1 vs. 3.2%, P < 0.008), respectively, the prevalence of other etiologies were the same in both genders.

Regarding the associated risk factors for HF, smoking was significantly higher in male patients (11.7 vs. 0%, respectively, P < 0.001), whereas atrial fibrillation and renal dysfunction were significantly higher in female patients (20.2 vs. 10.2%, P < 0.018) and (20.2 vs. 5.3%, P < 0.001), respectively. The prevalence of other associated risk factors was the same in both genders.

Echocardiography was performed for the vast majority of male and female patients equally (99% and 97.9%, respectively, P =0.42). However, ejection fraction was significantly higher in female patients compared to male patients (38.2% ± 16.9 vs. 30.4% ± 16.6, respectively, P < 0.001).

Drug treatment for HF patients

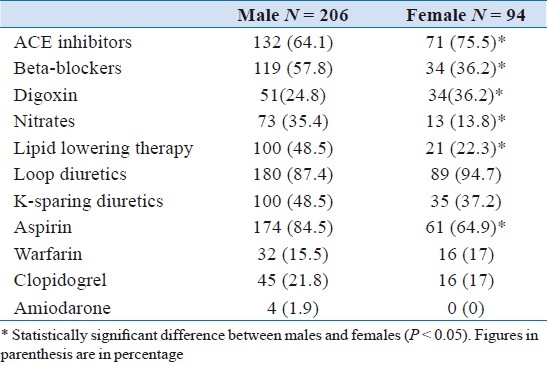

Table 2 shows gender differences in drug treatment of HF. Male patients with HF were prescribed ACE inhibitors and digoxin less significantly than female patients (64.1 vs. 75.5%. P < 0.049) and (24.8 vs. 36.2%, P < 0.042), respectively. Whereas female patients with HF were prescribed beta-blockers and nitrate therapies less significantly than male patients (36.2 vs. 57.8%, P < 0.001) and (13.8 vs. 35.4%, P < 0.001) respectively. In addition, aspirin and lipid lowering therapies were prescribed significantly less for female patients with HF compared to male patients (64.9 vs. 84.5%, P < 0.001) and (22.3 vs. 48.5%, P < 0.001), respectively. The rest of therapeutic agents used in treatment of HF were prescribed for both sexes without a significant difference.

Table 2.

Gender differences in drug treatment of heart failure

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The primary finding of this study relates to the presence of sex differences in both clinical presentation as well as management of HF patients admitted to ACH. Some of these differences are related to biologic differences between both genders, but others could be due to true gender bias in management of HF patients.

In our series ischemic etiology of HF was found more significantly in male patients compared to female patients. This sex difference was reported in other studies.[11,30–32] It is a well known fact that the male gender is a risk factor for IHD. HF due to IHD carries a worse prognosis than HF due to nonischemic causes, thus this finding of less prevalence of IHD in female patients with HF may reflect on better outcomes compared to male patients.

Smoking was significantly less in female patients compared to male patients, which was likely due to the local Saudi conservative sociocultural environment. Renal failure and atrial fibrillation are known risk factors for HF which make prognosis worse when they are associate with HF.[33,34] In our study, both risk factors were significantly more in female patients with HF compared to male patients. These findings make female patients in our series at greater risk regarding worse prognosis. Echocardiography is the mainstay investigational tool for the assessment of left ventricular function in HF patients, our series showed that echocardiography was performed on the vast majority of patients with HF, and there was no evidence of gender difference in utilizing this important investigation. Other reports showed evidence of sex-linked differences in investigating HF patients with less utilization of echocardiography in female patients with HF.[35] Ejection fraction is a practical and useful tool for assessing left ventricular function in HF patients and implicates a prognostication value. Female patients in our series had a better ejection fraction values compared to male patients, a similar finding detected in other studies.[11,32] This might reflect on a better survival in female patients with HF compared to male patients.

Certain therapeutic agents have shown survival benefit and improve morbidity when prescribed to HF patients (beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, K-sparing diuretics, and digoxin).[36–46] . In our series female patients with HF were significantly prescribed less beta-blockers than male patients with HF. Male patients with HF were prescribed significantly less ACE inhibitors and digoxin compared to female patients with HF.

The underutilization of beta-blockers in female patients with HF could be due to true gender bias or to lower incidence of ischemic etiology for HF in female patients, in which beta-blockers are indicated for ischemic indication.

While underutilization of ACE inhibitors and digoxin in male patients with HF compared to female patients with HF was an unexpected finding, this could be a true paradoxical gender bias (i.e. this time against male patients). There is no logical explanation for under-prescribing both therapies to male patients with HF. Interestingly a similar earlier finding was reported regarding under-prescription of digoxin to male compared to female patients.[47]

In conclusion, several baseline clinical and echocardiographic features were found in our series to differ significantly between women and men. Some characteristics are expected to confer a better prognosis, namely having a higher prevalence of nonischemic etiology, higher left ventricular ejection fraction. Some other features, however, have been related to worse outcome including higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation and renal dysfunction.

Gender differences in therapeutic management of HF were detected in both genders. Female patients were prescribed less beta-blockers while male patients were prescribed less ACE inhibitors and digoxin. The presence of this gender difference in the management of HF should be avoided by better adherence to evidence-based medicine regardless of a patient's gender.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hunt SA, Baker DW, Chin MH, Cinquegrani MP, Feldman AM, Francis GS, et al. Report of the ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Evaluation and management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult. Circulation. 2001;104:2996–3007. doi: 10.1161/hc4901.102568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Kannel WB. The natural history of congestive heart failure: The Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1441–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMurray JJ, Stewart S. Epidemiology, aetiology, and prognosis of heart failure. Heart. 2000;83:596–602. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.5.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosterd A, Hoes AW, de Bruyne MC, Deckers JW, Linker DT, Hofman A, et al. Prevalence of heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction in the general population. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:447–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith WM. Epidemiology of congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55:3A–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90789-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho KK, Anderson KM, Kannel WB, Groosman W, Levy D. Survival after the onset of congestive heart failure in Framingham Heart Study Subjects Circulation. Circulation. 1993;88:107–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilium RF. Heart Failure in the United States 1970–85. Am Heart J. 1987;113:1043–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghali JK, Cooper R, Ford E. Trends in rates for heart failure in the United States 1973-1986: Evidence for increasing population prevalence. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:769–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schocken DD, Arriata MI, Laever PE, Ross EA. Prevalence and mortality rate of congestive heart failure in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:301–6. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Massie BM, Nihir BS. Evolving trends in the epidemiologic factors of heart failure: Rationale for preventive strategies and comprehensive disease management. Am Heart J. 1997;133:703–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70173-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams KF, Jr, Sueta CA, Gheorghiade M, O′Connor CM, Schwartz TA, Koch GG. Gender differences in survival in advanced heart failure.Insights from the FIRST Study. Circulation. 1999;99:1816–21. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.14.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll JD, Carroll EP, Feldman T, Ward DM, Lang RM, McKaughey D, Karp RB. Sex-associated differences in left ventricular function in aortic stenosis of the elderly. Circulation. 1992;86:1099–107. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.4.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindenfeld J, Krause-Steinrauf H, Salerno J. Where are all the women with heart failure? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1417–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrie MC, Dawson NF, Murdoch DR, Davie AP, McMurray JJ. Failure of women's hearts. Circulation. 1999;99:2334–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.17.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendes LA, Davidoff R, Cupples LA, Ryan TJ, Jacobs AK. Congestive heart failure in patients with coronary artery disease: The gender paradox. Am Heart J. 1997;134:207–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zucker DR, Griffith JL, Beshansky JR, Selker HP. Presentations of acute myocardial infarction in men and women. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:79–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The SOLVD Investigators Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:685–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson K, Conroy RM, Mulcahy R, Hickey N. Risk factors and in hospital course of first episode of myocardial infarction or acute coronary insufficiency in women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:932–6. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)90048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kostis JB, Wilson AC, O′Dowd K, Gregory P, Chelton S, Cosgrove NM, et al. Sex differences in the management and long- term outcome of acute myocardial infarction: A statewide study. Circulation. 1994;90:1715–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between women and men hospitalized for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:221–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107253250401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jagal SB, Naylor CD. Sex Differences in the Use of Invasive Coronary Procedures in Ontario. Can J Cardiol. 1994;10:239–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw LJ, Miller DD, Romeis JC, Kargl D, Younis LT, Chaitman BR. Gender differences in the non-invasive evaluation and management of patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:559–66. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-7-199404010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H, Bairey-Merz CN, Cohen I, Cabico JA. Gender-related differences in clinical management after exercise nuclear testing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;26:1457–64. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00356-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregor RD, Bata IR, Eastwood BJ, Garner JB, Guernsey JR, Mackenzie BR. Gender differences in the presentation, treatment, and short term mortality of acute chest pain. Clin Invest Med. 1994;17:551–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz LM, Fisher ES, Tosteson ANA, Woloshin S, Chang C, Virnig BA. Treatment and health outcomes of women and men in a cohort with coronary artery disease. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1545–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maynard C, Althouse R, Cequeira M, Olsufka M, Kennedy JW. Underutilization of thrombolytic therapy in eligible women with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:529–30. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90791-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson ER, Anderson WA, Peacock WF, IV, Vaught L, Carley RS, Wilson AG. Effect of a patient's sex on the timing of thrombolytic therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27:8–15. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weaver WD, White HD, Wilcox RG, Aylward PE, Morris D, Auerci A. Comparisons of characteristics and outcomes among women and men with acute myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytic therapy. JAMA. 1996;275:777–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wenger NK. Exclusion of the elderly and women from coronary trials. JAMA. 1992;268:1460–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams KF, Sueta CA, Gheorghiade M, O′Connor CM, Schwartz TA, Koch GG, et al. Gender differences in survival in advanced heart failure: Insights from the FIRST study. Circulation. 1999;99:1816–21. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.14.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon T, Mary-Krause M, Funck-Brentano C. Sex differences in the prognosis of congestive heart failure: Results from the cardiac insufficiency bisoprolol study (CIBIS II) Circulation. 2001;103:375–80. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghali JK, Pin˜a IL, Gottlieb SS, Deedwania PC, Wikstrand JC. Metoprolol CR/XL in female patients with heart failure: Analysis of the experience in MERIT-HF. Circulation. 2002;105:1585–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012546.20194.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freiberger L, Heinisch RH, Bernardi A. Estudo de internações por cardiopatias em um hospital geral (Study of hospitalizations for heart disease in a general hospital) ACM Arq Catarin Med. 2004;33:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coelho FA, Moutinho MA, Miranda VA, Tavares LR, Rachid M, Rosa ML, et al. Associação da síndrome metabólica e seus componentes na insuficiência cardiac encaminhada da atenção primária (Association of metabolic syndrome and its components in heart failure referred from primary) Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007;89:42–51. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2007001300008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mejhert M, Holmgren J, Wändell P, Persson H, Edner M. Diagnostic tests, treatment and follow-up in heart failure patients-is there a gender bias in the coherence to guidelines? Eur J Heart Fail. 1999;1:407–10. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(99)00053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waagstein F, Bristow MR, Swedberg K, Camerini F, Fowler MB, Silver MA, et al. Beneficial effects of metoprolol in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 1993;342:1441–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92930-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CIBIS Investigators and Committees. A randomized trial of beta-blockade in heart failure: The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study (CIBIS) Circulation. 1994;90:1765–73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chadda K, Goldstein S, Byington R, Curb JD. Effect of propranolol after acute myocardial infarction in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1986;73:503–10. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lechat P. Prevention of heart failure progression: Current approaches. Eur Heart J. 1998;19:B12–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ergin A, Eryol NK, Unal S, Deliceo A, Topsakal R, Seyfeli E. Epidemiological and pharmacological profile of congestive heart failure at Turkish academic hospitals. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2004;4:32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). The CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1429–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706043162301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenberg B, Quinones MA, Koilpillai C, Limacher M, Shindler D, Benedict C, et al. Effects of long-term enalapril therapy on cardiac structure and function in patients with left ventricular dysfunction.Results of the SOLVD Echocardiography substudy. Circulation. 1995;91:2573–81. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.10.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The Digitalis Investigation Group. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:525–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Packer M, Gheorghiade M, Young JB, Costantini PJ, Adams KF, Cody RJ, et al. Withdrawal of digoxin from patients with chronic heart failure treated with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307013290101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uretsky BF, Young JB, Shahidi FE. Randomized study assessing the effect of digoxin withdrawal in patients with mild to moderate chronic congestive heart failure: Results of the PROVED Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:955–62. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90403-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harjai KJ, Nunez E, Stewart Humphrey J, Turgut T, Shah M, Newman J. Does gender bias exist in the medical management of heart failure? Int J Cardiol. 2000;75:65–9. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(00)00298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]