Abstract

Background

To assess the racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes and their association with process of care measures for Medicare elderly with localized prostate cancer.

Methods

We used SEER-Medicare databases for the period 1995–2003. African American, non-Hispanic white and Hispanic men with localized prostate cancer were identified and data was obtained for the one year period prior to the diagnosis of prostate cancer and up to eight years of post-diagnosis period. Short-term outcomes were complications, ER visits, readmissions and mortality. Long-term outcomes were prostate cancer-specific and all-cause mortality. Process of care measures were treatment and time to treatment. Cox proportional hazard, logistic and Poisson regressions were used to study the racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes and their association with process of care measures.

Results

Compared with non-Hispanic white patients, African-American patients (Hazard ration [HR], 1.43; 95% confidence interval [CE], 1.19-1.86) and Hispanic patients (HR=1.39; 95% CI-1.03-1.84) had greater hazard of long term prostate specific mortality. African American patients had higher odds of ER visits (Odds Ratio=1.4, CI=1.2, 1.7) and higher all-cause mortality (HR=1.39, CI=1.3, 1.5) compared to white patients. Time to treatment was longer for African American patients and was indicative of higher hazard of all-cause long-term mortality. Hispanic patients receiving surgery or radiation had higher hazard of long-term prostate-specific mortality compared to white patients receiving hormone therapy.

Conclusion

Racial and ethnic disparity in outcome is associated with process of care measures (type and time to treatment). There exists opportunity to reduce these disparities by addressing the process of care measures.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, quality of care, mortality, health resource utilization, race and ethnicity, radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer is the most common malignancy among men in the U.S. The burden of prostate cancer on the healthcare system is immense in both human and economic terms [1]. Added to this, substantial disparities exist in the pattern of prostate cancer care and outcomes across institutions, regions, age and ethnic groups [1–8]. Racial and ethnic disparities also have been documented in various phases of prostate cancer care. Improving the quality of health care across racial and ethnic groups requires attention to the process and outcomes of health services rendered to individuals, with adequate adjustments for various risk factors and personal characteristics [2,8,9]. Though a priority in the health policy arena, quality of care continues to be uneven [1,2,8]. Addressing the variation in quality of care is widely regarded as an important healthcare policy objective and racial and ethnic disparities in quality of care are recognized as a major quality problem [2–11]. Increased variability in care pattern and outcome is linked to lack of agreement in identification of quality of measures [2–11].

The SEER-Medicare linked data has been used to document the variation in health resource utilization and outcomes for prostate cancer [4–7]. African American men were less likely to receive aggressive therapy (OR=0.74, CI=0.70 – 0.79) compared to non-Hispanic white men [6,12]. Additionally, African American men receiving curative treatment reported a differential recovery pattern compared to non-Hispanic white men with prostate cancer [13]. Due to higher use of prostate specific antigen screening coupled with uncertainty in screening and treatment effects, debate on the effectiveness of various treatments continues. In another study using SEER-Medicare data by Godley et al., racial and ethnic disparities were evident both in overall and prostate cancer-specific survival [14]. African American patients had poorer overall survival among those undergoing surgery [14,15]. Studies indicate that treatments for a given stage of prostate cancer vary by geographic region, age and race and ethnicity [4–7,12–24]. In men undergoing prostatectomy, the rates of postoperative and late urinary complications are significantly reduced if the procedure is performed in a high-volume hospital and by a high-volume surgeon [16].

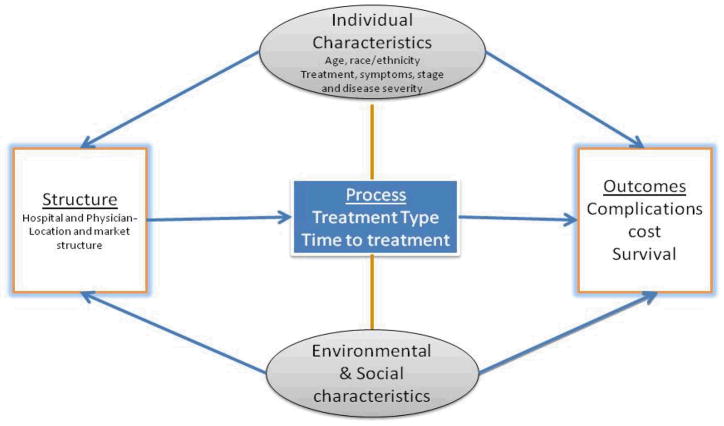

Conceptual Model of Quality of Care

Quality of healthcare is defined as the degree to which healthcare services for individual patients and populations increase the probability of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge [3,10]. As shown in Figure-1, our conceptual model of quality of care consists of three main components - structure, process and outcomes [9,25]. The structural component consists of characteristics of hospitals, physicians and other healthcare workers and is defined as the “resource used by providers or organizations to support the delivery of care to patients” [8–11]. Process of care includes the way physicians and patients interact, the appropriateness and timeliness of treatment and other clinical and non-clinical factors associated with care. The outcome is derivative of the structure and process and includes change in patient health status, satisfaction with care, health related quality of life and functional status [8–11].

Figure 1.

Quality of Care- Conceptual Model

Efforts to reduce racial and ethnic disparities must acknowledge the multidimensional nature of quality of care. There exists paucity in knowledge regarding the process of care factors that contribute to racial and ethnic disparity in prostate cancer outcomes among Medicare elderly. Hence, the objective of this study was to analyze the interplay of process of care measures (treatment type and time to treatment) and patient characteristics and their relationship with short-term outcomes (mortality, complications, re-admissions and ER visits) and long-term outcomes (prostate-specific and all cause mortality) among elderly prostate cancer patients. We used Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked data to examine the racial and ethnic disparity in outcomes and their association with quality of care measures for elderly African American, Hispanic and non-Hispanic white men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer. We hypothesized that some of the racial and ethnic disparity in prostate cancer outcomes can be explained by the process of care measures.

METHODS

Data Sources and Study Sample

We adopted a retrospective design using the linked SEER-Medicare databases. All African American, Hispanic and non-Hispanic white men, aged 66 years and older, and diagnosed with prostate cancer (ICD codes: 185, 233.4, 236.5) between 1995 and 1998 (n=50, 147) were identified. From this cohort, we retained those with localized stage (n=42,522). Of these, 8,476 were excluded due to non availability of treatment and treatment date in SEER and Medicare claims data, leading to a final cohort of 34,046 patients. For this cohort, data was obtained for the one year period prior to the diagnosis of prostate cancer and up to eight years of post-diagnosis period. The lists of procedure codes, revenue center codes and service codes were reviewed to ensure that appropriate codes were used for each year, since Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes change over time.

The SEER-Medicare linked database brings together Medicare administrative claims data and clinical tumor registry data for Medicare recipients [26]. The SEER program collects data on cancer incidence, treatment and mortality in a representative sample of the US population. The data used in this analysis included 13 SEER sites (San Francisco, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, Seattle, Utah, Atlanta, San Jose, Los Angeles, Rural Georgia, and Alaska), encompassing 14% of the US population. With the exception of individuals who are enrolled in health maintenance organizations or who do not have Part B coverage, Medicare data provides information about all inpatient and outpatient utilization of medical care for residents of the US, 65 years and older. SEER-Medicare file integrates the individual’s SEER and Medicare records into a single data file. Of persons in the SEER registry that were diagnosed with cancer at age ≥ 65, 93% have been matched with their Medicare enrollment records, in a linked customized file-the Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary File. In addition to SEER diagnostic information, this file provides Medicare entitlement, utilization and census tract and zip code based socioeconomic data. SEER database provides characteristics of the tumor that are crucial to adequately adjust for disease severity, including histology, stage and grade. SEER also provides information on the extent of disease that may have prognostic significance such as size of primary tumor, and extent and location of lymph node involvement. The SEER-Medicare linked record includes service codes in three Medicare files: (1) Inpatient file; (2) Hospital outpatient standard analytical file (claims for outpatient facility services); and (3) Physician part B file (claims for physician and other medical provider services).

Measurement Strategy

Process of Care Measures

As depicted in the conceptual model (Figure-1), process of care measures are: (1) Treatment type and (2) Time to treatment. Treatment was categorized into three groups. The surgery group includes mono therapy (surgery alone) or multimodal therapy (surgery with external beam radiation therapy or brachytherapy, or surgery with combination of radiation and hormone therapy). The radiation therapy group included radiation therapy alone (external beam radiation or brachytherapy) or radiation therapy with hormonal therapy (multimodal). The third treatment group consisted of hormone therapy alone. Time to treatment (number of days) was defined as time between diagnosis and treatment.

Outcome measures

Short term outcome measures (within 30 days from treatment date) are: (1) mortality; (2) complications; (3) Number of readmissions and (4) Number of ER admissions. Long term outcome measures (up to eight years) are prostate cancer-specific and overall mortality. Survival was determined by Medicare vital statistics as well as SEER linkage to death certificates (National Death Index). Consistent with Alibhai et al (2007, 2009) and Beard et al, (1997), using Medicare inpatient and outpatient claims data, we identified the following groups of complications that occurred within 30 days from treatment - cardiac, respiratory, vascular, wound/bleeding, genitourinary, bowel, miscellaneous medical and miscellaneous surgical [27–31].

Disease severity and demographic covariates

Disease severity was adjusted by using data on prostate cancer stage, grade and histology from SEER database. Charlson comorbidity index was used to assess medical comorbidity using inpatient and outpatient Medicare claims [32,33]. We used diagnostic information from all encounters in one year prior to prostate cancer diagnosis to determine comorbidity as outlined by Klabunde et al [32,33]. Age, race and ethnicity, marital status, geographic area and income data was obtained from the PEDSF.

Statistical Analysis

We tested for the underlying difference in demographic and clinical attributes between African-American, Hispanic and non-Hispanic white patients using t- tests and chi-sq tests. As indicated in our conceptual model (Figure 1), our analyses consisted of two sets of models. In the first set (Models 1–6), we analyzed the association between race and ethnicity and outcomes (short term mortality, complications, number of re-admission and ER visits, prostate cancer-specific mortality and all cause mortality). Cox proportional hazard model was used for mortality outcomes, logistic regression was used for modeling any complication and Poisson models (with zero inflation corrections) were used to model the number of ER visits and readmissions, after adjusting for age, marital status, income, TNM stage, grade, comorbidity and SEER region. The primary variable of interest in all models was race and ethnicity [34,35]. In the second set of models, we analyzed the modifying effects of process of care measures on outcomes. A separate model was developed for treatment (Model 7) and time to treatment (Model 8). We also tested for the effect of interaction of race and ethnicity and process of care measure on outcomes. Analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The study sample consisted of 34,046 localized prostate cancer patients. As shown in Table 1, mean age of the non-Hispanic white group was slightly higher than other groups. The small difference in mean age was statistically significant, possibly due to the large sample size. Also, marital status and Median income differed between the three groups. African American men were less likely to be married and had lower income compared to their non-Hispanic white and Hispanic counterparts. The mean Charlson comorbidity score was higher for African American men, compared to other groups.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (n=34,046)

| Variables | White (n=28,200) | African American (n=3642) | Hispanic (n=2,204) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at diagnosis (SD) | 73.1 (5.4) | 72.4 (5.1) | 72.5 (5.4) | <.0001 |

| Geographic Area (%) | <.0001 | |||

| Metro | 86.8 | 98.5 | 91.9 | |

| Urban and Rural | 13.2 | 1.5 | 8.1 | |

| Marital Status (%) | <.0001 | |||

| Married | 75.8 | 59.3 | 73.6 | |

| Single | 19.2 | 34.5 | 22.0 | |

| Unknown | 5.0 | 6.2 | 4.4 | |

| Charlson comorbidity Mean (SD) | 0.33 (0.86) | 0.60 (1.1) | 0.08 (0.44) | <.0001 |

| Annual median income of census tract Mean (SD) | 42330 (19176) | 25979 (13237) | 33408 (13574) | <.0001 |

| Grade (%) | <.0001 | |||

| Well differentiated | 10.07 | 7.6 | 11.9 | |

| Moderately differentiated | 65.62 | 66.4 | 61.5 | |

| Poorly/undifferentiated | 24.31 | 26.0 | 26.6 | |

| Stage (%) | <.0001 | |||

| ≤T2a | 48.1 | 46.2 | 48.5 | |

| T2b and T2c | 41.6 | 40.7 | 39.8 | |

| ≥T3a | 10.3 | 13.1 | 11.7 |

Abbreviations: SD=Standard deviation

Variation in Process and Outcome Measures

Unadjusted comparison of process and quality of care measures showed significant variation between racial and ethnic groups (Table 2). A higher proportion of Hispanic patients received radical prostatectomy (mono or multi-modal), while a higher proportion of African American patients received external beam radiation therapy (mono or multi-modal). African American group had longer mean time to treatment from date of diagnosis (95.8 days, p<.0001), and higher all-cause mortality. Higher proportion of African American patients had ER visits within 30 days of treatment, whereas, higher proportion of white patients had inpatient visits. Overall, proportion of patients with any complication was higher among non-Hispanic white and Hispanic groups compared to African American group.

Table 2.

Unadjusted process and quality of care measures across racial and ethnic groups (n=34,046)

| White (n=28,200) | African American (n=3,642) | Hispanic (n=2,204) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (%) | <.0001 | |||

| Surgery (mono therapy or multimodal therapy) | 42.3 | 35.1 | 47.9 | |

| 47.5 | 50.6 | 39.3 | ||

| Radiation therapy (mono therapy or multimodal therapy) | 12.2 | 14.3 | 12.8 | |

| Hormone therapy alone | ||||

| Time to treatment (number of days-mean ± SD) | 64.9 (142.3) | 95.8 (231.9) | 60.6 (111.4) | <.0001 |

| Median | 31.0 | 59.0 | 31.0 | |

| ER visits-within 30 days of treatment (%) | 3.41 | 4.78 | 2.99 | <.0001 |

| Inpatient hospitalization –within 30 days of treatment (%) | 33.94 | 28.47 | 33.71 | <.0001 |

| Complications -30days- (%) | ||||

| Any | 22.06 | 20.81 | 22.87 | 0.1345 |

| Cardiac | 2.76 | 2.9 | 2.36 | 0.4375 |

| Respiratory | 1.63 | 1.76 | 1.59 | 0.6793 |

| Vascular | 0.62 | 0.55 | 0.41 | 0.9345 |

| Wound | 9.59 | 8.1 | 9.07 | 0.0004 |

| Genito urinary | 10.2 | 10.85 | 11.12 | 0.5183 |

| Miscellaneous | 4.47 | 4.39 | 5.22 | 0.0009 |

| Miscellaneous surgery | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.7803 |

| Bowel | 1.96 | 2.44 | 2.51 | 0.0075 |

| Short term all cause mortality-30 days (%) | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.4419 |

| All cause mortality -8 years follow-up (%) | 19.99 | 25.89 | 18.10 | <.0001 |

| Prostate cancer specific mortality- 8 years follow-up (%) | 1.59 | 2.03 | 2.04 | 0.0549 |

Abbreviations: SD=Standard deviations;

Table 3 presents results of Cox models for association between race and ethnicity and outcomes, with adjustments for age, marital status, TNM stage, comorbidity, geographic area and SEER region. Race and ethnicity was not associated with short term all cause mortality. Compared to non-Hispanic white patients, Hispanic patients had higher odds of any complications (odds ratio (OR) =1.12, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.02, 1.22). African American patients had higher number of ER visits and lower number of inpatient visits, compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts (OR = 1.64, CI =1.42, 1.89 and OR=0.93, CI=0.89, 0.99, respectively). African American (Hazard Ratio (HR) = 1.43, CI=1.19, 1.86) and Hispanic (HR=1.39, CI=1.03, 1.84) patients had higher hazard of prostate cancer specific mortality, compared to non-Hispanic white patients. African American patients also had higher hazard of overall long-term mortality (HR=1.39, CI=1.30, 1.50) compared to non-Hispanic white patients.

Table 3.

Association between Race and Ethnicity and outcomes (n=34,046)

| Short Term |

Long Term (up to eight years) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Model 1) Mortality (HR, CI) |

(Model 2) Any complications (OR, CI) |

(Model 3) Number of ER visits (OR, CI) |

(Model 4) Number of inpatient visits (OR, CI) |

(Model 5) Prostate cancer specific mortality (HR, CI) |

(Model 6) All cause mortality (HR, CI) |

|

| African American | 1.52 (0.92, 2.6) | 1.06 (0.92, 1.15) | 1.64 (1.42, 1.89) | 0.93 (0.89, 0.99) | 1.43 (1.19, 1.86) | 1.39 (1.3, 1.5) |

| Hispanic | 1.7 (0.89, 3.3) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.25) | 1.04 (0.83, 1.29) | 1.02 (0.94, 1.1) | 1.39 (1.03, 1.84) | 0.93 (0.84, 1.01) |

| Reference: white | ||||||

| Age | 1.2 (1.14, 1.39) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.15) | 1.1 (1.09, 1.10) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 1.13 (1.10, 1.42) | 1.1 (1.1, 1.13) |

| Married | 0.67 (0.45, 0.98) | 0.99 (0.93, 1.14) | 0.76 (0.68, 0.85) | 1.0 (0.98, 1.11) | 0.79 (0.66, 0.94) | 0.81 (0.77, 0.85) |

| TNM stage: | ||||||

| T2b andT2c | 0.49 (0.38, 0.79) | 0.69 (0.66, 0.74) | 0.72 (0.64, 0.82) | 0.73 (0.69, 0.76) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.91) | 1.13 (1.1, 1.2) |

| ≥T3a | 0.93 (0.54, 1.6) | 0.73 (0.67, 0.79) | 1.10 (0.89, 1.3) | 0.76 (0.72, 0.81) | 3.6 (2.8, 4.5) | 2.74 (2.39, 2.69) |

| (reference)≤T2a | ||||||

| Geographic area: | ||||||

| Metro | 0.41 (0.27, 2.7) | 0.55 (0.42, 0.67) | 0.69 (0.49, 1.05) | 0.75 (0.66, 0.86) | 0.73 (0.39, 1.3) | 0.78 (0.65, 0.92) |

| Urban | 0.82 (0.28, 2.3) | 0.90 (0.74, 1.11) | 0.99 (0.65, 1.53) | 0.98 (0.86, 1.12) | 1.0 (0.55, 1.9) | 0.94 (0.78, 1.12) |

| (reference) Rural | ||||||

| Charlson comorbidity | 1.04 (0.73, 1.33) | 1.07 (1.04, 1.09) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.22) | 0.95 (0.93, 0.97) | 1.07 (1.04, 1.10) | 1.07 (1.04, 1.5) |

Abbreviations: HR=Hazard ratio, OR=Odds ratio, CI=confidence interval

Modifying Effect of Process of Care Measures on Racial and Ethnic Disparity in Outcomes

Models 7–8 present the effects of the interactions of process of care measures and race and ethnicity on short term outcomes (Table 4). As seen from Model 7, interaction of race and ethnicity and treatment type was not associated with 30 day all cause mortality. However, Hispanic men receiving radiation therapy were less likely to have complications (OR=0.56, CI=0.33, 0.95) compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts receiving hormone therapy (Table 4). Similarly, African American patients receiving surgery or radiation were less likely to have higher ER visits or higher number of inpatient visits, compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts receiving hormone therapy. As noted from Model 8, African American patients receiving longer time to treatment had higher odds of number of ER visits (OR=1.4, CI=1.2, 1.7). Interaction of race and ethnicity and treatment type was not associated with all cause mortality or with prostate cancer specific mortality (Table 5). However, African American patients with longer time to treatment exhibited higher odds for all cause mortality (HR=1.1, CI=1.05, 1.2) compared to non-Hispanic white patients. Hispanic patients receiving surgery (HR=5.4 CI=1.6, 18.1) or radiation therapy (HR=5.4 CI=1.5, 19.7) had higher hazard of long-term prostate specific-mortality compared to non-Hispanic whites receiving hormone therapy.

Table 4.

Association between race and ethnicity, process variable and short term (30 days) outcomes (n=34,046)

| Models | Mortality (HR, CI) | Any complications (OR, CI) | Number of ER visits (OR, CI) | Number of inpatient visits (OR, CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 7-Interaction between race and treatment* | ||||

| Race: | ||||

| African American | 1.9 (0.65, 5.7) | 1.41 (0.97, 1.8) | 2.7 (1.9, 3.61) | 1.5 (1.2, 1.8) |

| Hispanic | 2.6 (0.77, 8.9) | 1.04 (0.71, 1.54) | 1.3 (0.71, 2.2) | 1.19 (0.82, 1.5) |

| White (reference) | ||||

| Treatment: | ||||

| Surgery | 1.7 (1.0, 2.94) | 6.8 (5.71, 7.7) | 1.9 (1.6, 2.39) | 5.9 (4.69, 6.4) |

| Radiation Therapy | 0.14 (0.05, 0.39) | 0.61 (0.54, 0.69) | 0.46 (0.37, 0.57) | 0.42 (0.38, 0.48) |

| Hormone alone (reference) | ||||

| Interaction: | ||||

| African American X surgery | 0.64 (0.17, 2.43) | 0.77 (0.57, 1.14) | 0.51 (0.36, 0.73) | 0.64 (0.52, 0.79) |

| African American X radiation therapy | 1.7 (0.23, 12.1) | 0.78 (0.55, 1.12) | 0.52 (0.33, 0.82) | 0.71 (0.54, 0.95) |

| Hispanic X surgery | 0.50 (0.12, 2.2) | 0.99 (0.66, 1.5) | 0.72 (0.38, 1.4) | 0.79 (0.58, 1.1) |

| Hispanic X radiation therapy | 0.05 (0.10, 1.3) | 0.56 (0.33, 0.95) | 0.64 (0.27, 1.5) | 0.88 (0.58, 1.3) |

| Model 8-Interaction between race and time to treatment* | ||||

| Race: | ||||

| African American | 0.70 (0.05, 11.1) | 1.17 (0.83, 1.50) | 0.56 (0.43, 0.85) | 1.16 (0.86, 1.39) |

| Hispanic | 0.35 (0.02, 5.3) | 1.56 (1.08, 2.52) | 1.3 (0.57, 2.83) | 0.99 (0.77, 1.31) |

| White (reference) | ||||

| Time to treatment | 0.19 (0.12, 0.30) | 0.75 (0.73, 0.77) | 0.72 (0.68, 0.77) | 0.79 (0.78, 0.81) |

| African American X time to treatment | 1.30 (0.46, 3.93) | 0.99 (0.89, 1.14) | 1.40 (1.16. 1.67) | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) |

| Hispanic X time to treatment | 1.9 (0.67, 5.12) | 0.91 (0.82, 1.01) | 0.93 (0.76, 1.21) | 0.99 (0.94, 1.14) |

All models are adjusted for age, marital status, stage, comorbidity and geographic area.

Abbreviations: HR=Hazard ratio; OR= Odds ratio; CI=confidence interval

Table 5.

Association between race and ethnicity, process variable and long term (up to eight years) outcomes (n=34,046)

| Models | All cause mortality (HR, CI) | Prostate specific mortality (HR, CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Model 7-Interaction between race and type of treatment (surgery)* | ||

| Race: | ||

| African American | 1.3 (1.10, 2.61) | 1.3 (0.82, 2.1) |

| Hispanic | 0.79 (0.63, 0.99) | 0.30 (0.09, 0.95) |

| White (reference) | ||

| Treatment: | ||

| Surgery | 0.83 (0.77, 0.89) | 0.89 (0.71, 1.1) |

| Radiation therapy | 0.63 (0.58, 0.67) | 0.35 (0.27, 0.46) |

| Hormone therapy (reference) | ||

| Interaction: | ||

| African American X surgery | 1.02 (0.87, 1.2) | 1.2 (0.64, 2.1) |

| African American X radiation therapy | 1.10 (0.91, 1.3) | 1.0 (0.54, 2.1) |

| Hispanic X surgery | 1.20 (0.88, 1.5) | 5.4 (1.6, 18.1) |

| Hispanic X radiation therapy | 1.31 (0.96, 1.7) | 5.4 (1.5, 19.7) |

| Model 8-Interaction between race and time to treatment* | ||

| Race: | ||

| African American | 1.13 (0.86, 1.4) | 1.40 (0.60, 3.2) |

| Hispanic | 0.79 (0.55, 1.13) | 1.4 (0.49, 4.2) |

| White (reference) | ||

| Time to treatment | 0.80 (0.78, 0.82) | 0.72 (0.65, 0.79) |

| African American X time to treatment | 1.1 (1.05, 1.2) | 1.0 (0.82, 1.3) |

| Hispanic X time to treatment | 1.1 (0.95, 1.2) | 0.98 (0.72, 1.4) |

All models are adjusted for age, marital status, stage, comorbidity and geographic area.

Abbreviations: HR=Hazard ratio; OR= Odds ratio; CI=confidence interval

DISCUSSION

Medicare enrolled elderly prostate cancer patients show great variability in healthcare utilization, variation in morbidity and other quality outcomes [1–8]. Quality of care in prostate cancer is a multidimensional construct consisting of structure, process and outcomes. Racial and ethnic disparities in prostate cancer care are documented for each phase of care - prevention, treatment, follow-up and terminal care [4–7, 12–24]. In continuation of our prior research on quality of prostate cancer care assessment, in this study we document the modifying effect of process of care measures on the racial and ethnic differences in prostate cancer outcomes using administrative database. To begin with, we found that in concordance with earlier research, our results confirmed racial and ethnic disparities in prostate cancer outcomes [4–7]. We observed racial and ethnic disparity in the process of care measures (treatment type and time to treatment). Mean and median time to treatment was higher for African American patients, who were also more likely to receive radiation therapy. The results lend substantial support to our hypothesis that some of the racial and ethnic disparity in prostate cancer outcomes can be explained by the process of care measures. Longer time to treatment among African American patients was indicative of higher hazard of overall mortality as well as higher number of ER visits. Also, Interaction of treatment and race and ethnicity was significant was outcomes of complications, ER visits, inpatient visits and mortality (prostate cancer specific and overall).

The journey to assessing quality of care measures in the arena of prostate cancer began with the explorations in variations in outcomes across geographic region, age and racial and ethnic groups. Foundation for assessing quality of care was built by earlier RAND studies [36–43]. These studies used Donabedian model of structure, process, and outcome to conceptualize dimensions of quality of care. Quality of care assessment is essential to develop appropriate clinical and healthcare policy measures to address the burden exerted by prostate cancer. In a premier study, Spencer et al (2003) developed 63 potential indicators and covariates to measure quality of care in prostate cancer [40]. Quality of care in prostate cancer is a multidimensional construct that encompasses various levels of care and clinical and environmental domains [36]. Given the multiple treatment options for localized prostate cancer, quality of care measures are useful for comparing treatment efficacy and variations across provider and geographic level attributes. Process of care quality indicators were found to be superior for those receiving radiation therapy compared to those receiving radical prostatectomy [38]. Examination of compliance with twenty-five quality of care measures developed by RAND to assess structure and process indicated significant variation across hospital type and census based geographic regions [43]. A recent study showed that prostate cancer treatments differed significantly between county hospitals and private providers [44]. Though these studies have successfully applied quality of care measures, there is clear room for further measurement and assessment of quality of prostate cancer care [41].

Our findings must be considered in light of limitations that are intrinsic to SEER-Medicare linked dataset. The study sample includes only African American, Hispanic and non-Hispanic white men over 66 years of age who lived in a SEER area and were not enrolled in a HMO. Although SEER is designed to provide a representative sample of the U.S., it includes only relatively small Hispanic population. However, the age and sex distribution for individuals 66 years and older in the SEER areas are comparable with that of the US elderly population. Our findings may not be generalizable to men under 66 or men enrolled in HMOs. While Medicare claims data provide excellent opportunity to analyze prostate cancer care in a broad population, these data have certain limitations. Though our analysis controlled for treatment and other covariates, there is potential for some unaccounted bias. Finally, as depicted in the conceptual model, in the study we do not address the effect of measures of structure (such as hospital and physician attributes), and other potential process of care measures on outcomes. Our goal is to address these in future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

Health care quality, a key concept for medical practice and research, is also a widely used construct in healthcare administration and market research. A major concern of policymakers in the U.S. is the persistent presence of unacceptable variation in quality of care across racial and ethnic groups [1–12]. The first step in eliminating these disparities is to identify their determinants and minimize the overuse, under-use and misuse of health resources, while accounting for individual preferences. More importantly policy measures are needed to identify and implement strategies at the geographic level, health system level, and individual level attributes. A two dimensional approach can be address the issues of quality of care. One dimension is the internal or system/individual level effort to improve the quality of care. The second dimension is the broader or external level where monitoring efforts can be incorporated via collaborations among organizations such as AUA, NCI, ASCO and AHRQ. Some of the measures that can be adopted at the external level are establishing guidelines and achievable performance targets, infusion of technology and expertise, monitoring structure and process measures to ensure enhanced outcomes and finally, providing the necessary funding.

Consistent with earlier studies, our study revealed ethnic variations in quality of care and outcomes. However, our data suggests opportunities to reduce these disparities. For example, the large difference in time to treatment, approximating a full month, suggests the need for an aggressive, patient centered approach immediately after the diagnosis is established. Systems can be modified to ensure that the initial appointment with patient and family occurs as soon as possible. During the first and subsequent visits, practitioners can demonstrate sensitivity to the emotional impact of this diagnosis, explore attitudes of suspiciousness and distrust, and exhibit respect for the individual as a person. Health systems can implement proactive, aggressive monitoring systems from diagnosis, through treatment and early recovery, to ensure that minority patients do not delay the care because of lack of understanding, or miscommunications. Last, these data speak to the need for health systems and health plans to identify minority patients. Without the identification, issues of health equity cannot be measured and therefore, cannot be improved.

In summary, significant opportunity exists to minimize ethnic variations in process of care and improve the overall quality of care. In the era of value based healthcare and accountability in healthcare, it is vital to consider these factors while developing appropriate performance incentives to minimize ethnic disparity in prostate cancer care. We have developed a conceptual model of quality of care that consists of elements of structure, process and outcome of care. This model was envisioned in order to facilitate linkage of the multiple dimensions of quality of care and our study is a small step in this direction. Many studies have shown that structure of care such as hospital and physician is associated with improved outcomes. Future studies are planned to identify additional measures of structure and process and their association with racial and ethnic disparity in outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health-Grant # 5RO3CA 121338-2 and Penn RCMAR 5P30AG031043-03

References

- 1.Penson DF, Chan JM. Urologic Diseases in America. In: Litwin MS, Saigal CS, editors. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Chapter 4. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2007. pp. 71–123. NIH Pub. No. 07-5512. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smedley BD, et al., editors. Institute of medicine of the national academies. The NAP; Washington, D.C: 2003. Unequal treatment-confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm-A new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross CP, Smith BD, Wolf E, Anderson M. Racial Disparities in cancer therapy-did the gap narrow between 1992 and 2002. CANCER. 2008;112:900–908. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Underwood W, 3rd, Jackson J, Wei JT, et al. Racial Treatment trends in localized/regional prostate carcinoma: 1992–1999. CANCER. 2005;103:538–545. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeliadt SB, Potosky AL, Etzioni R, et al. Racial Disparity in primary and adjuvant treatment for nonmetastatic prostate cancer: SEER-Medicare trends 1991 to 1999. Urology. 2004;64:1171–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirby JB, Taliaferro G, Zuvekas SH. Explaining racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Medical Care. 2006;44(5):I-64–I-72. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000208195.83749.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold MR, et al. Inequality in quality: addressing socioeconomic, racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(19):2579–2584. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1966;44:166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lohr KN, editor. IOM. Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn KL, Malin JL, Adams J, Ganz PA. Developing a reliable, valid and feasible plan for quality-of-care measurement for cancer How should we measure? Medical Care. 2002;40(6 Supp):II-73–III-85. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200206001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Underwood W, De Monner S, Ubel P, et al. Race/ethnicity disparities in the treatment of localize/regional prostate cancer. Journal of Urology. 2004;171:1504–1507. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000118907.64125.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayadevappa R, Johnson JC, Chhatre S, et al. Ethnic Variations in Return to Baseline Values of Patient Reported Outcomes in Older Prostate Cancer Patients. CANCER. 2007;109 (11):2229–38. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godley PA, Schenck AP, Amamoo A, et al. Racial difference in mortality among Medicare recipients after treatment for localized prostate cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95 (22):1702–10. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu KC, Tarone RE, Freeman HP. Trends in prostate cancer mortality among black men and white men in the US. CANCER. 2003;97:1507–1516. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, et al. Outcomes of localized prostate cancer following conservative management. Journal of American Medical Association. 2009;302 (11):1202–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins AS, Whittemore AS, Van Den Eeden SK. Race, prostate cancer survival and membership in a large health maintenance organization. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998;90:986–90. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.13.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polednak AP. Prostate cancer treatment in black and white men: The need to consider both stage at diagnosis and socioeconomic status. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1998;90:101–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shavers VL, Brown ML, Potosky AL, et al. Race/ethnicity and the receipt of watchful waiting for the initial management of prostate cancer. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19:146–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao H, Warrick C, Huang Y. Prostate cancer treatment patterns among racial/ethnic groups in Florida. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2009;101 (9):936–943. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayadevappa R, Chhatre S, Bloom BS, et al. Medical care cost of patients with prostate cancer. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2005;(23):155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Harlan LC, et al. Trends and Black-White differences in treatment for nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Medical Care. 1998;36 (9):1337–1348. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krupski TL, Kwan L, Afifi AA, et al. Geographic and socioeconomic variation in the treatment of prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23 (31):7881–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell IJ, Dey J, Dudley A, et al. Disease-free survival difference between African Americans and whites after radical prostatectomy for local prostate cancer: A multivariate analysis. Urology. 2002;59:907–912. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01609-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jayadevappa R, Schwartz SC, Chhatre S, et al. Satisfaction with care: a measure of quality of care in prostate cancer patients. Medical Decision Making. 2010;30:234–245. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09342753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data-content, research application and generalizability to the United States Elderly Population. Medical Care. 2002;40(supp):IV-3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Virnig BA, Warren JL, Cooper GS, et al. Studying radiation therapy using SEER-Medicare-Linked data. Medical Care. 2002;40(supp):IV-49–54. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Potosky AL, Warren JL, Riedel ER, et al. Measuring complications of cancer treatment using the SEER-Medicare Data. Medical Care. 2002;40(supp):IV-62–68. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alibhai SMH, Leach M, Tomlinson G, et al. 30-day mortality and major complications after radical prostatectomy: Influence of age and comorbidity. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007;97 (20):1525–1532. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alibhai SMH, Leach M, Warde P. Major 30day complications after radical radiotherapy. CANCER. 2009;115:293–302. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beard CJ, Propert KJ, Rieker PP, et al. Complications after treatment with external beam irradiation in early stage prostate cancer patients: A prospective multi institutional outcomes study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15(1):223–229. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klabunde CN, Warren JL, Legler JM. Assessing comorbidity using claims data-an overview. Medical Care. 2002;40(supp):IV-26–35. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Medical Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green WH. Econometric Analysis. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allison PD. Logistic regression –suing the SAS system: Theory and Application. Cairy, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller DC, Montie JE, Wei JT. Measuring the quality of care for localized prostate cancer. The Journal of Urology. 2005;174:425–431. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000165387.20989.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malin JL, Schneider EC, Epstein AM, et al. Results of the National Initiative for Cancer Care Quality: how can we improve the quality of cancer care in the United States? Journal Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:626–634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller DC, Spencer BA, Ritchey J, et al. Treatment choice and quality of care for men with localized prostate cancer. Medical Care. 2007;45:401–409. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000255261.81220.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Litwin MS, Steinberg M, Malin JL, et al. Prostate cancer patient outcomes and choice of providers: Development of an infrastructure for quality assessment. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spencer BA, Steiberg M, Malin J, et al. Quality-of-care indicators for early stage prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:1928–1936. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller DC, Saigal CS. Quality of care indicators for prostate cancer: progress toward consensus. Urologica Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2009;27:427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller DC, Litwin MS, Sanda MG, et al. Use of quality indicators to evaluate the care of patients with localized prostate carcinoma. CANCER. 2003;97:1428–1435. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spencer BA, Miller DC, Litwin MS, et al. Variations in quality of care for men with early-stage prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;20 (22):3735–3742. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parsons JK, Kwan L, Connor SE, et al. Prostate cancer treatment for economically disadvantaged men: a comparison of county hospitals and private providers. CANCER. 2010;116(5):1378–84. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]