Abstract

The structural maintenance of chromosome 1 (Smc1) protein is a member of the highly conserved cohesin complex and is involved in sister chromatid cohesion. In response to ionizing radiation, Smc1 is phosphorylated at two sites, Ser-957 and Ser-966, and these phosphorylation events are dependent on the ATM protein kinase. In this study, we describe the generation of two novel ELISAs for quantifying phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966. Using these novel assays, we quantify the kinetic and biodosimetric responses of human cells of hematological origin, including immortalized cells, as well as both quiescent and cycling primary human PBMC. Additionally, we demonstrate a robust in vivo response for phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 in lymphocytes of human patients after therapeutic exposure to ionizing radiation, including total-body irradiation, partial-body irradiation, and internal exposure to 131I. These assays are useful for quantifying the DNA damage response in experimental systems and potentially for the identification of individuals exposed to radiation after a radiological incident.

INTRODUCTION

In the event of a nuclear or radiological incident in a heavily populated area, the surge in demand for medical evaluation will likely overwhelm our emergency care system, compromising our ability to care for victims with life-threatening injuries or exposures. Historically during such events, much of the surge in demand has come from individuals who neither were exposed to radiation nor required acute medical intervention. Rather, most individuals presenting for care have been victims of mass panic. Hence effective emergency management of a nuclear or radiological event will require two sequential stages: initial rapid identification of exposed individuals among the masses of unexposed followed by triage of victims to dose-appropriate medical interventions based on accurate biodosimetry. Unfortunately, there is a critical unmet need for the radiation diagnostics required to perform both of these stages of emergency management.

Developing procedures for triage and medical management of exposed individuals is complicated by uncertainties concerning the nature of exposure. For example, the severity of injury to individual organs varies with radiation dose rate, quality of radiation (low or high linear energy transfer, LET), heterogeneity of exposure (partial or total body), and source of exposure (external radiation or internal contamination) and is likely modulated by the host’s inherent sensitivity. Physical dosimetry would be essentially impossible. Only biodosimetry has the potential to quantify individual exposures for guiding dose-appropriate medical intervention.

Assays presently available for biodosimetric determinations suffer from inaccuracy, high expense and/or long analysis times, and many are not amenable to point-of-care use in emergency conditions. The “gold standard” for radiation biodosimetry is cytogenetic analysis (chromosome aberrations, micronuclei) of peripheral blood lymphocytes (1). This provides a highly accurate measure of exposure that has the potential to distinguish exposures to different LETs, and it can be used when there are partial-body exposures, thanks to the continual mixing of lymphocytes in blood. Its limitations are that assays take 2–3 days and require culture of cells in laboratories; the assays are not portable. Another parameter, lymphocyte depletion kinetics, requires multiple measurements over many days and leads to dose estimations that are too late for most intervention therapies (2-6). Finally, estimating exposure using time to onset of vomiting is highly inaccurate given the variability of the prodromal syndrome (6, 7). This critical unmet need for adequate radiation exposure biomarkers has stimulated searches for sensitive markers of exposure including gene expression profiles (8-13), protein profiles (14-16), urine metabolomic profiles (17, 18), and changes in tooth enamel (19) as well as work toward automating chromosomal assays to enable high-throughput measurements.

In an effort to identify proteomic changes that may be useful for radiation biodosimetry, we previously performed a large-scale screen that identified 55 ionizing radiation-responsive proteins in human blood-derived cells, including 14 targets not previously reported to be radiation-responsive at the protein level (15). As part of this prior study, we also demonstrated that phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 are induced in peripheral blood cells after total-body irradiation (TBI) in a canine model, demonstrating the feasibility of using blood cell-based proteomic changes for diagnosing radiation exposure.

The structural maintenance of chromosome 1 (Smc1) protein is a member of the highly conserved cohesin complex and is involved in sister chromatid cohesion. The protein forms a heterodimer with the Smc3 protein through the “hinge” domains of each protein. Both Smc1 and Smc3 form functional ATPase domains through the intramolecular association of their N- and C-terminal domains. These ATPase domains are held in place by the α-kleisin complex (Scc1/Mcd1/Rad21), forming a ring structure that maintains the sister chromatids in proximity (20, 21). Smc1 and Smc3 have also been identified as subunits of a distinct recombination complex, RC-1, which also contains DNA polymerase ε and DNA ligase III (22).

In response to ionizing radiation, Smc1 is phosphorylated at two sites, Ser-957 and Ser-966, in a dose- and time-dependent manner. These phosphorylation events are dependent on the ATM protein kinase (23). The significance of the phosphorylation of Smc1 at these two sites was demonstrated by the overexpression of Smc1 constructs where either one or both phosphorylation sites were mutated from serine to alanine. HeLa cells expressing these dominant negative mutant alleles of Smc1 were defective in their intra-S-phase checkpoint and showed increased radiosensitivity (23). Additional experiments using RNA interference-mediated knock-down of Smc1 in HeLa cells also demonstrated the radiosensitivity of these cells, as measured by the kinetics for γ-H2AX/53BP1 foci and cell survival assays (24). Experiments using a Cre-mediated “knockin” of a non-phosphorylatable Smc1 construct under normal genetic control resulted in the same phenotype, loss of S-phase checkpoint and reduced cell viability after exposure to radiation (25, 26). These results suggest the Smc1 is a critical member of the DNA damage response (DDR) network.

In these current studies, we report the development of two novel enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for the quantification of phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966. We characterize these assays by quantifying phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 after exposure of human cells to radiation in vitro and ex vivo, including cultured human lymphoblast lines, cultured human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), and PBMCs from human whole blood irradiated ex vivo. Additionally, we demonstrate induction of phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 in circulating cells after therapeutic exposure of human patients to ionizing radiation, including total-body irradiation, partial-body irradiation, and internal exposure to 131I. These assays are useful for quantifying the DDR response in experimental systems and potentially for the identification of individuals exposed to radiation after a radiological incident.

METHODS

Peptides for Immunization

All peptides used for immunization, screening and standards were synthesized by Chinese Peptide Company (Hangzhou, China). Three peptides were used for immunization; the first peptide (CGSGSQEEGS[p]SQGEDSVSG) corresponds to human Smc1 amino acids 951 to 965 and was synthesized with a phospho-serine at position 957. The second immunization peptide (CGSGDSVSG[p]SQRISS) corresponds to human Smc1 amino acids 961 to 971 with a phosphoserine at position 966. The third immunization peptide (CGCGDLTKYPDANPNPNEQ) corresponds to the C-terminus of the Smc1 protein starting at position 1219. All three immunization peptides were synthesized with an N-terminal linked CGCG spacer. Two peptides were synthesized for counterscreening and are the non-phosphorylated counterparts of the two phospho immunization peptides (CGSGSQEEGSSQGEDS and CGSGDSVSGSQRISS). Two additional peptides were generated for ELISA standards: Smc1_F_Cp (ISQEEGS-pS-QGEDSDLTKYPDANPNPNEQ) and Smc1_F_Dp (EDSVSG-pSQ-RISSIDLTKYPDANPNPNEQ). Both standard peptides contain the C-terminal sequence of Smc1 (AAs 1219 to 1233), which is concatenated with the sequence surrounding either pS957 (AAs 950–962) or pS966 (AAs 960–972). An additional peptide with no homology to Smc1 was used as a nonspecific control in a peptide competition assay: ETWSLPL-pS-QNSASELPASQPQIIEDYESDGT. Peptides used in this study are summarized in Table 1. Standard and control peptide concentrations were determined by Amino Acid Analysis (New England Peptide, Gardner, MA).

TABLE 1.

Summary of Peptides and Monoclonal Antibodies Generated in This Study

| Peptide name | Peptide sequencea | Peptide type | Monoclonal antibodies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smc1-3p | CGSGSQEEGS[p]SQGEDSVSG | immunogen | FHC37Cp-33-1 |

| Smc1-4p | CGSGDSVSG[p]SQRISS | immunogen | FHC37Dp-202-3 |

| Smc1-6 | CGSGDLTKYPDANPNPNEQ | immunogen | FHC37F-6-3 |

| Smc1-3 | CGSGSQEEGSSQGEDS | counter-screen | none |

| Smc1-4 | CGSGDSVSGSQRISS | counter-screen | none |

| FHC37_F_Cp | ISQEEGS-pS-QGEDSDLTKYPDANPNPNEQ | ELISA standard | FHC37F-6-3 and FHC37Cp-33-1 |

| FHC37_F_Dp | EDSVSG-pS-QRISSIDLTKYPDANPNPNEQ | ELISA standard | FHC37F-6-3 and FHC37Dp-202-3 |

pS represents phospho-serine.

Immunization

Rabbit immunizations were conducted by Epitomics Inc. (Burlingame, CA). Each immunization peptide was independently conjugated through the N-terminal cystines to KLH carrier molecules and injected into two 3–4-month-old female New England White rabbits. The rabbits were boosted every 3 weeks for a total of five injections. Sera were collected prior to the first injection and 14 days after the final injection.

Antibody Purification

Antibody was purified from rabbit sera and hybridoma supernatants using HiTrap Protein A HP columns (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Briefly, sera were diluted 1:2 with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to loading. Hybridoma supernatants (2 to 45 ml) were loaded directly onto prewashed columns. The column was washed with PBS and eluted with 0.1 M citric acid (pH 3.0). Three 0.5-ml fractions were collected in tubes containing 0.125 ml 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 9.0) to give a final pH of ~7.4. Protein concentration was determined with the Bradford assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA), and the two or three most concentrated antibody fractions were pooled.

Antibody Quantification

Antibody concentration was determined by the Bradford assay (BioRad) or by OD280 using a bovine gamma globulin IgG (Pierce, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) standard curve.

Antibody Labeling

Detection antibodies FHC37Cp-33-1 and FHC37Dp-202-3 were biotinylated with the FluoReporter® Mini-Biotin-XX Protein Labeling Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Lymphoblast Cell Cultures

Cells of five lymphoblast cell lines (GM07057, GM10833, GM10860, GM03187 and GM01526) were obtained from the Coriell Institute (Camden, NJ), and cells were grown at 37°C and 95% air/5% CO2 in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 units/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were suspended at 106 cells/ml in fresh medium in T-25 flasks and allowed to equilibrate at 37°C, 95% air/5% CO2 for 36 to 40 h before treatment with ionizing radiation.

Blood Samples

Healthy, nonpregnant adults that had not previously received chemotherapy or radiation treatments were recruited from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC) and/or the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (SCCA) and informed consent was obtained under FHCRC-approved protocols. Informed consent was obtained under FHCRC approved protocols from patients recruited from the SCCA that either were undergoing TBI as part of a conditioning regimen for bone marrow transplantation or were receiving radioimmunotherapy for the treatment of lymphoma. Patients undergoing localized radiation therapy of solid tumors were recruited from the Virginia Mason Medical Center (VMVC), and informed consent was obtained under VMVC-approved protocols. Whole blood samples were collected by venipuncture into K2EDTA tubes and maintained at ambient temperature during transportation to the laboratory.

PBMC Isolation and Culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from whole blood either by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient or red blood cell (RBC) lysis. For Ficoll-Hypaque isolation, whole blood was diluted with an equal volume of PBS, layered over a half volume of Ficoll-Hypaque (density = 1.077) at room temperature, and centrifuged at 900g for 20 min. PBMCs were harvested from the Ficoll-plasma interface with a plastic transfer pipette, treated with Red Cell Lysis Buffer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), and washed twice with PBS.

For PBMCs isolated by RBC lysis, whole blood was mixed with two volumes of RBC lysis buffer (Fisher Scientific) preheated to 37°C and incubated at room temperature with gentle mixing on a Nutator Single-Speed Orbital Mixer (Fisher Scientific) for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 400g for 8 min and treated three more times with RBC lysis buffer. After the final lysis step, cells were rinsed in ice-cold PBS.

PBMC activation and culturing was done in either RPMI-1640 medium or Iscove’s medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 U/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml IL-2 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), and 3 μl/ml CD3/CD28 beads (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained at 0.5–2 × 106 cells/ml for 7 to 10 days at 37°C, 95% air/5% CO2. Cells were resuspended at 0.5 × 106 cells/ml in fresh medium in T-25 flasks and allowed to equilibrate at 37°C, 95% air/5% CO2 for 36 to 40 h before treatment with ionizing radiation.

Cell Irradiations

Cells or whole blood samples were irradiated in a J. L. Shepherd Mark I irradiator using a 137Cs source delivering a dose rate of 5.3 Gy/min. Control cells were mock-irradiated; the mock-irradiated cells were handled in the same manner as the irradiated cells but the irradiator was not turned on.

Protein Lysates

After cellular irradiation or mock treatment, flasks were returned to the incubator for the indicated times. Cells were harvested in prechilled tubes, aliquots were removed for counting, and cells were spun down and washed two times in an equal volume of ice cold PBS. Cell counting was done with a Beckman Coulter Z1 Particle Counter. Cells were lysed at 108 cells/ml in whole cell lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM b-Glycerophosphate, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.005% Tween 20, filter sterilized) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). All lysates were stored in liquid nitrogen and thawed on ice.

λ-Protein Phosphatase Treatment

Protein lysates were generated as above but without the addition of the phosphatase inhibitors. One milligram of lysate was diluted to 400 μl in 1× reaction buffer and incubated with 800 U of λ-protein phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) for 30 min at 30°C. Lysates were returned to ice and used immediately or stored in liquid nitrogen.

Western Blotting

Protein lysates (25 to 50 μg/lane) were adjusted to 1× NuPAGE® LDS Sample Buffer containing NuPAGE® Sample Reducing Agent (Invitrogen) and heated to 98°C for 5 min before being subjected to SDS-PAGE on Tris-Acetate or Bis-Tris Novex gels (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to 0.45-μm nitrocellulose membranes using an XCell II™ Blot Module (Invitrogen). Membranes were placed in 50-ml conical tubes (Falcon 352070, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes NJ) and blocked for 1 h in SuperBlock (Pierce) with 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma) on a rotisserie rotator (Barnstead/Thermolyne, Dubuque, IA) at room temperature. Blocking agent was aspirated away, and protein-A purified antibody was diluted 1:500 and incubated overnight at 4°C in 1× PBS, 10% SuperBlock and 0.1% Tween 20. Membranes were washed two times with 10 ml 1× PBS, 0.1% Tween 20. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) diluted 1:2000 in 1× PBS, 10% SuperBlock and 0.1% Tween 20 was added to the membrane and incubated 1 h at room temperature on a rotisserie rotator. Secondary antibody was aspirated away and the membrane was washed two times with 10 ml 1× PBS, 0.1% Tween 20, 5 min/wash. Then 1× LumiGLO substrate (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) was added and incubated 5 min at room temperature on a rotisserie rotator. The membrane was then exposed to film (CL-XPosure, Pierce), developed, scanned and digitized. Commercial Smc1 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies and used at the manufacturer’s recommended dilutions.

Immunoprecipitation

Thirty microliters of protein-A beads (Invitrogen) were washed 2× in PBS and then incubated with 50 μg of protein lysate in a volume of 100 μl for 1 h at 4°C with mixing by end-over-end tumbling. The protein-A beads were pelleted by centrifugation and the lysates were transferred to a fresh tube and incubated with 30 μl of serum or hybridoma supernatant for 1 h at 4°C with mixing by tumbling. An additional 30 μl of protein-A beads were washed 2× in PBS and then added to the lysate/antibody mix and incubated for an additional hour at 4°C with mixing by tumbling. The protein-A beads were pelleted by centrifugation and washed 2× in PBS, and the antigen was recovered by heating to 98°C for 5 min in 1× LDS loading buffer. Samples were the subjected to SDS-PAGE and evaluated by Western blotting.

Detailed ELISA Procedure

ELISAs were developed in 96-well Costar (EIA/RA Plate no. 3369) plates using rabbit monoclonal antibody FHC37F-6-3 as a capture antibody and biotinylated rabbit monoclonals FHC37Cp-33-1 and FHC37Dp-202-3 as the detection antibodies. Hybrid phospho-peptides were used as calibration standards. The detailed ELISA protocol is as follows:

Coat polystyrene 96-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY) overnight at 4°C with 50 μl/well with FHC37F-6-3 antibody diluted to 6 μg/ml in PBS.

Wash plate three times with 300 μl/well with 1× PBS, 0.05% Tween 20 using an automated plate washer (BioTek ELx405™, Winooski, VT).

Block plates for 1 h at room temperature on an orbital shaker with 150 μl/well Blocking Buffer [10% SuperBlock (Pierce), 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma)].

Wash plates three times with automated plate washer.

Prepare standard phospho-peptide curve by twofold serial dilution in Diluent Buffer (1 mM EDTA, 0.005% Tween 20, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1× PBS, 1% BSA).

Dilute protein lysates in Diluent Buffer and add 50 μl/well; incubate 1 h at room temperature on an orbital shaker.

Wash plates three times with automated plate washer.

Dilute biotinylated detection antibodies FHC37Cp-33-1 (242 ng/ml) or FHC37Dp-202-3 (182 ng/ml) in Diluent Buffer, add 50 μl/well and incubate 1 h at room temperature on an orbital shaker.

Wash plates three times with automated plate washer.

Dilute streptavidin-conjugated HRP (Invitrogen) 1:2000 in Diluent Buffer and incubate 1 h at room temperature on an orbital shaker.

Wash plates three times with automated plate washer.

Add 50 μl/well TMB substrate (Sigma) and incubate at room temperature for 1 to 5 min. Reaction is stopped by the addition of 50 μl/well of 0.4 N HCl.

Measure OD 450 on for end point assays or OD 640 every 40 s over 12 min for kinetic assays on a BioTek Synergy2 plate reader.

Peptide Competition Assay

Protein lysates were generated from LBL GM10834 at 4 h after exposure to 5 Gy. Lysates were diluted 1:80 in dilution buffer and either competitive peptide or the nonspecific control peptide was added at multiple concentrations ranging from 2 pM up to 20 nM. The amount of endogenous phosphorylated Smc1 protein (p-Smc1pS957 and p-Smc1pS966) was measured by ELISA.

Mixing Experiment

Protein lysates were generated from LBL GM10834 4 h after mock exposure or exposure to 5 Gy. The lysates were diluted either 1:160 (p-Smc1pS957 assay) or 1:40 (p-Smc1pS966 assay) in dilution buffer and then mixed at different ratios. The concentration of phosphorylated Smc1 protein was determined by ELISA and quantified by the standard peptide curve.

Standard Addition Experiment

Standard peptide was added to either cell lysate from mock-irradiated LBL GM10834 (diluted 1:20 in dilution buffer) or directly to dilution buffer. The concentration of the spiked standard peptides was determined by ELISA and quantified using the standard peptide curve.

RESULTS

Generating Monoclonal Antibodies against Smc1 Total Protein, Phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and Phospho-Smc1Ser-966

Our goal was to generate well-characterized, renewable reagents for generating ELISA assays to quantify phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 in clinical and biological samples. Two rabbits were immunized for each of three Smc1 peptide immunogens (Table 1), two of which contained the phospho-sites of interest. All sera (pre- and postimmune) were screened by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting against lysates from lymphoblasts treated with 0 (mock) or 10 Gy of ionizing radiation (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Additionally, the phospho-specificity of the sera targeting phospho-epitopes was confirmed by demonstrating the sensitivity of the sero-reactivity to λ-protein phosphatase treatment of protein lysates derived from irradiated cells (data not shown). Animals were selected for splenectomy and hybridoma fusion based on the robustness of their immune responses relative to the preimmune sera.

After fusion and initial subcloning, positive primary clones were identified by peptide ELISA using the immunization peptide conjugated to BSA. Twenty-eight positive primary clones were further screened by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. Primary clones that passed the Western blot screen were then selected for subcloning by serial dilution, and 22 secondary clones were again screened by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. Selected clones (Supplementary Fig. 1B) were expanded for antibody production, and purified antibodies were used for ELISA development, as described below. The peptides and the corresponding antibodies generated in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Development and Validation of ELISA Assays for Quantifying Phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and Phospho-Smc1Ser-966

To generate quantification standards for sandwich ELISA-based measurement of phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966, we synthesized two hybrid reference peptide standards (Table 1). These standard peptides contain the C-terminal sequence of Smc1 (amino acids 1219–1233) concatenated with the sequence surrounding either pS957 (amino acids 950–962) or pS966 (amino acids 960–972). The concentrations of the hybrid reference peptide standards were determined by amino acid analysis.

ELISA development was done using the hybrid reference peptide standards. Specifically, assay parameters were systematically and iteratively optimized by varying two variables at a time in a 96-well plate format and selecting the conditions that generated the optimal signal-to-noise ratio for each parameter evaluated. Parameters optimized included coating buffer, timing of plate coating, capture antibody concentration, blocking buffer composition, blocking buffer concentration, diluent buffer, detection antibody labeling, detection antibody concentration, HRP-conjugate, HRP-conjugate concentration, lysate buffer, sample dilution buffer, standard peptide dilution, and substrate. The final, optimized protocol is presented in detail in the Methods section.

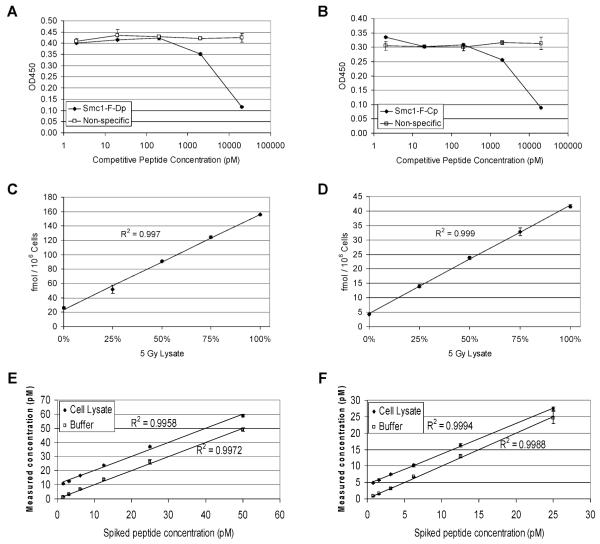

Specificity of the ELISAs was determined by competition experiments. Protein lysate derived from LBL GM10834 cells 4 h after exposure to 5 Gy was spiked with increasing concentrations of either a competitive peptide or a nonspecific control peptide. The competitive peptide for the phospho-Smc1Ser-957 was the standard peptide used in the phospho-Smc1Ser-966 assay, Smc1_F_Dp. This peptide contains the epitope recognized by the capture antibody coupled with the phospho-epitope recognized by the detection antibody FHC37Dp-202-3. With increasing concentrations of the Smc1_F_Dp peptide, there is a decreasing signal detected for the endogenous phosphorylated Smc1pS957 protein as measured by ELISA (Fig. 1A). Similarly, when the lysate is spiked with increasing concentrations of the Smc1_F_Cp peptide, there is a similar competitive loss in the ability to measure levels of the endogenous phosphorylated Smc1pS966 protein (Fig. 1B). Moreover, the specificity of the ELISA for Smc1 was confirmed in four additional ways (data not shown). First, we demonstrated that if the wells of the ELISA plate were blocked with BSA and not coated with capture antibody before the addition of sample (i.e., protein lysate from irradiated LBL or standard peptide), no signal above background was detected. Second, we demonstrated that if protein lysates or peptides were incubated with a molar excess of capture antibody before being added to wells coated with the capture antibody, no signal above background was detected. Both results confirm that the FHC37F-6-3 capture antibody is required. Third, we demonstrated that when the sample (either lysate from irradiated LBL or standard peptide) was incubated with a molar excess of unlabeled detection antibody before the addition of the biotinylated detection antibody, no signal above background was detected. Finally, the phospho-specificity of the ELISA assays was evaluated by treating protein lysates or standard phospho-peptides with λ-protein phosphatase. When de-phosphorylated protein lysates or peptides were used, no signal above background was detected.

FIG. 1.

Validation of ELISA assays. All raw ELISA data are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Panels A and B: Specificity of the assays was determined using competitive peptides. GM10834 cells were treated with 5 Gy of ionizing radiation, and protein lysates were generated 4 h after exposure. Lysates were diluted 1:80 in dilution buffer containing the indicated concentration of competitive or nonspecific peptide, and concentrations of endogenous phosphorylated Smc1 protein were measured by ELISA. The competitive peptide was Smc1_F_Dp for the phospho-Smc1(pS957) assay (panel A) and Smc1_F_Cp for the phospho-Smc1(pS966) assay (panel B). Panels C and D: Linearity of the assays was determined using mixing experiments. GM10834 cells were treated with 5 Gy of ionizing radiation or mock-irradiated, and protein lysates were generated 4 h after exposure. The 5-Gy and 0-Gy lysates were mixed in the indicated proportions. The concentration of phosphorylated Smc1 protein was determined by the phospho-Smc1(pS957) assay (panel C) or the phospho-Smc1(pS966) assay (panel D) using an external peptide calibration curve. The concentrations were normalized to cell count. Panels E and F: Recovery of the assays was determined using standard addition of the peptide to cell lysate matrix. The indicated amount of standard peptide was added to either cell lysate from mock-irradiated GM10834 cells (1:22 final dilution) or to dilution buffer. The concentration of spiked Smc1_F_Cp peptide in each sample was measured using the phospho-Smc1(pS957) assay (panel E), and the concentration of spiked phospho-peptide Smc1_F_Dp was measured by phospho-Smc1(pS966) assay (panel F). Results represent triplicate measurements, and error bars represent standard deviations.

The linearity of the assays was demonstrated using standard mixing experiments. Protein lysates derived from LBL GM10834 cells 4 h after exposure to 5 Gy or mock-irradiated were mixed at different ratios, and the levels of phosphorylated Smc1 protein were determined by the phospho-Smc1Ser-957 ELISA (Fig. 1C) or the phospho-Smc1Ser-966 ELISA (Fig. 1D) using external peptide calibration curves. The R-squared values were greater than 0.99 for both assays.

The recovery of the assays was demonstrated using standard addition of the control peptide to the lysate matrix. Standard peptide was added either to protein lysate from mock-irradiated LBL GM10834 or to dilution buffer (the standard curve). The concentrations of spiked Smc1_F_Cp peptide in each sample were measured using the phospho-Smc1Ser-957 assay (Fig. 1E), and spiked phospho-peptide Smc1_F_Dp concentrations were measured by the phospho-Smc1Ser-966 assay (Fig. 1F). The offset of the cell lysate relative to the buffer is due to low levels of endogenous phospho-Smc1 protein in the cell lysate.

Phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and Phospho-Smc1Ser-966 Show Dose- and Time-Dependent Accumulation in Human Lymphoblasts Exposed to Radiation

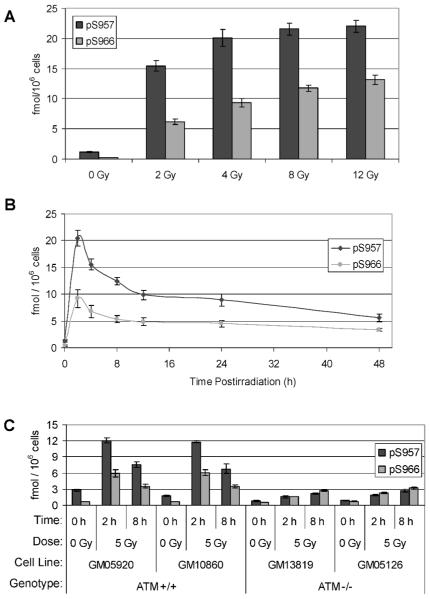

Once the ELISAs had been optimized, they were tested on protein lysates derived from human lymphoblasts after X irradiation or mock irradiation. Both phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 ELISAs detected a dose-dependent accumulation of their respective phospho-analytes between 0 and 12 Gy (Fig. 2A). The radiation-induced level of Smc1Ser-957 was approximately twofold higher than that of Smc1Ser-966 across the dose range tested, whereas the baseline level of Smc1Ser-966 (i.e., in the mock-irradiated sample) was higher than that of Smc1Ser-957. Hence, at 12 Gy there was a 50-fold increase in phospho-Smc1Ser-966 analyte compared to the mock-irradiated sample, while there was a 19-fold increase for the phospho-Smc1Ser-957. Additionally, a time course study after 5 Gy irradiation revealed parallel kinetic responses for both phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966; the levels of both analytes peaked by 2 h after radiation exposure, with the phospho-Smc1Ser-957 ELISA showing a 16-fold induction over baseline and the phospho-Smc1Ser-966 showing a 24-fold induction over baseline (Fig. 2B). Although the response gradually trailed off after peaking by 2 h postirradiation, both phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 remained ~fivefold elevated 48 h after exposure. The ELISA results were corroborated by Western blotting in an independent set of lysates (Supplementary Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Dose-, time- and ATM-dependent responses of Smc1 phosphorylation in human lymphoblasts. All raw ELISA data are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Panel A: Two sets of protein lysates were generated from GM07057 cells 2 h after mock irradiation (0 Gy) or irradiation (2–12 Gy). Lysates were evaluated by ELISA for Smc1 phosphorylation at pS957 and pS966. Each lysate was run in triplicate on two independent plates. The mean concentrations of p-Smc1 (pS957) and p-Smc1 (pS966) were calculated from the standard peptide curve, and the values were normalized to cell count. Values are means ± SD. The average inter-well variation of the measurement was 2.2% for both assays for all dilutions of all lysates across all four plates. The average inter-plate concentration variation was 6% for the p-Smc1(pS957) assay and 4% for the p-Smc1(pS966) assay for all lysates across all plates. Panel B: Two sets of protein lysates were generated from GM07057 cells at the indicated times after mock irradiation (0-h samples) or irradiation with 5 Gy. Lysates were evaluated by ELISA for Smc1 phosphorylation at pS957 and pS966. Each lysate was run in triplicate on two independent plates. The mean concentrations of p-Smc1 (pS957) and p-Smc1 (pS966) were calculated from the standard peptide curve, and the values were normalized to cell count. The average inter-well variation of the measurement was 2.6% for the pS957 assay and 8.6% for the pS966 assay for all dilutions of all lysates across all four plates. The average inter-plate variation was 8.6% for the p-Smc1(pS957) assay and 11.6% for the p-Smc1(pS966) assay for all lysates across all plates. Panel C: Two independent sets of protein lysates were generated from cells of each of four lymphoblast cell lines (ATM+ G05920 and GM10860, ATM− GM13819 and GM05126) at 2 and 8 h after exposure to 5 Gy; control cells were mock-irradiated. Lysates were evaluated by ELISA for Smc1 phosphorylation at pS957 and pS966. Each lysate was run in duplicate and the concentrations of p-Smc1 (pS957) and p-Smc1 (pS966) were calculated from the standard peptide curve. Phospho-Smc1 levels across both lysates are plotted as means ± SD.

The Phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and Phospho-Smc1Ser-966 ELISAs Quantify the Severe Defect in ATM− Cells in Response to Radiation

Cells from patients afflicted with the genetic disorder ataxia telangiectasia (AT) are severely defective in Smc1 phosphorylation in response to ionizing radiation due to a lack of ATM-encoded kinase activity (23, 27). To determine whether our phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 ELISAs could detect this deficiency in AT patient-derived cells, we measured these phospho-analytes in protein lysates derived from ATM+ and ATM− lymphoblasts at 2 and 8 h after exposure to 5 Gy radiation. As expected, the ATM− lymphoblasts showed very low levels of induction of phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 compared with ATM+ cells (Fig. 2C). The low level of phospho-induction in ATM− cells has been described (23) and is likely due to redundant kinase activity of other PI3-kinase family members.

Phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and Phospho-Smc1Ser-966 Induction in Human PBMC after X Irradiation In Vitro or Ex Vivo

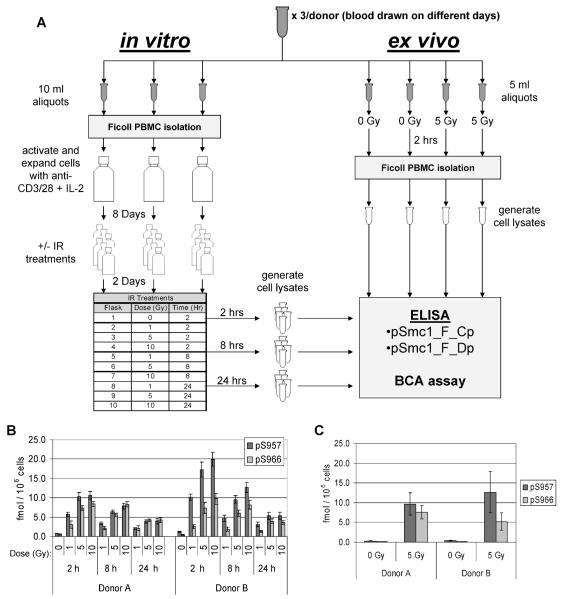

We next determined whether our ELISAs could detect radiation-induced phosphorylation of Smc1 in nonimmortalized human cells of hematological origin in both cycling and quiescent states. After informed consent was obtained, blood was collected by phlebotomy from a healthy 31-year-old male donor (donor A) on three different occasions over 1 month (dates of collection were February 1, February 16 and March 2).

At the time of each of the three collections, seven independent aliquots of blood were prepared as depicted in Fig. 3A. Three 10-ml aliquots were used for technical replicates to examine the response of cycling human PBMCs (shown in the left, in vitro arm in Fig. 3). Specifically, PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll gradient, and the cells were placed in culture and activated with anti-CD3/28 antibodies plus IL-2. Cells were cultured for 8 days and then split into treatment flasks and grown for an additional 2 days. Cells were either mock-irradiated (0 Gy) or exposed to 1, 5 or 10 Gy and returned to the incubator. Cells were harvested at 2, 8 and 24 h postirradiation, and protein lysates were prepared from the cells and evaluated by ELISA in duplicate on two independent ELISA plates.

FIG. 3.

Experimental design for evaluating the phospho-Smc1 response in cycling and quiescent primary human PBMC. Panel A: Blood was collected by phlebotomy from two healthy donors at three different times over a 1-month period. For each sample, seven independent aliquots of blood were prepared as follows: Three 10-ml aliquots were used for technical replicates to examine the response of cycling human PBMCs (shown in the left, “in vitro” arm). PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll gradient, and the cells were placed in culture and activated with anti-CD3/28 antibodies plus IL-2. Cells were cultured for 8 days and then split and grown for an additional 2 days. Cells were either mock-irradiated (0 Gy) or irradiated and returned to the incubator. Cells were harvested at 2, 8 and 24 h after irradiation, and protein lysates were prepared from the cells and evaluated by ELISA in duplicate on two independent ELISA plates (results are shown in Fig. 4A and Supplementary Table 1). In parallel, four 5-ml aliquots were used to examine the response of noncycling human PBMCs (shown in the right, “ex vivo” arm). Two of the blood aliquots were mock-irradiated (0 Gy) and two aliquots were exposed to 5 Gy, and blood was incubated for 2 h. PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll gradient, and protein lysates were prepared from the cells and evaluated by ELISA in duplicate on two independent ELISA plates (results are shown in Fig. 4B and Supplementary Table 1). Panel B: In vitro exposures. Each blood draw was divided into three technical replicates. PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll gradient and the cells were placed in culture and activated with anti-CD3/28 antibodies plus IL-2. Cells were cultured for 8 days and then split and grown for an additional 2 days. Cells were either mock-irradiated (0 Gy) or irradiated. Cells were harvested 2, 8 and 24 h after exposure, and protein lysates were prepared and evaluated by ELISA in duplicate. The mean concentrations of p-Smc1(pS957) and p-Smc1(pS966) were calculated from the standard peptide curve and the values were normalized to cell count. The means ± SD of the values of all measurements for all technical replicates from all three blood draws are plotted. Panel C. Ex vivo exposures. For each of the same three blood draws described in panel A, four additional aliquots of whole blood were set up. Two were mock-irradiated (0 Gy) and two were exposed to 5 Gy. PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll gradient at 2 h after exposure, protein lysates were prepared, and phospho-protein concentrations were measured by ELISA in duplicate. The mean concentrations of p-Smc1(pS957) and p-Smc1(pS966) were calculated from the standard peptide curves, and the values were normalized to cell count. The mean concentration ± SD for all technical replicates from the three blood draws is plotted.

In parallel, four 5-ml aliquots of blood were used to examine the response of noncycling human PBMCs (shown in the right, ex vivo arm in Fig. 3A). Specifically, two of the blood aliquots were mock-irradiated (0 Gy), two aliquots were exposed to 5 Gy, and blood was incubated at 37°C, 95% air/5% CO2 for 2 h, at which time PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll gradient, and protein lysates were prepared from the cells and evaluated by ELISA in duplicate on two independent ELISA plates.

For the cycling cells (i.e., the in vitro arm of the experiment summarized in Fig. 3A), we saw maximum induction of phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 by 2 h (Fig. 3B). At 2 h, the 5- and 10-Gy levels were within one standard deviation of each other, suggesting that the sites were nearing saturation at these doses and this time. At 8 h postirradiation, there were reduced levels of both analytes relative to 2 h, but there was a clear separation of all three doses. At 24 h postirradiation, both phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 levels remained elevated; for example, the signals in the 1-Gy samples were three to four times higher than that in the mock-irradiated samples. For the quiescent cells (i.e., the ex vivo arm of the experiment) (Fig. 3C), we saw induction of both phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 to levels comparable to those observed in the genetically identical cycling cells at the same dose and time (5 Gy, 2 h) (Fig. 3B).

The entire process depicted in Fig. 3A was repeated independently with blood from a second donor (a healthy 24-year-old male, donor B) that was drawn on three different occasions over 5 weeks (dates of collection were March 29, April 20 and May 3). Cells from this donor showed qualitatively similar results (Figs. 3B and C), although a potentially more robust induction of phospho-Smc1Ser-957 was seen at 2 and 8 h in the in vitro experiment (see Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S3).

FIG. 4.

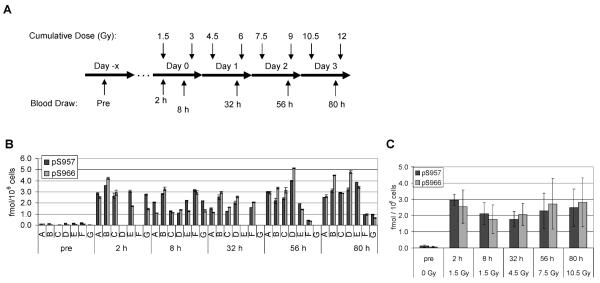

Phospho-Smc1 levels in human PBMCs isolated from patients after total-body radiation (TBI). Panel A: Diagram of the treatment regimen for patients undergoing conditioning for bone marrow transplantation. Patients received 1.5 Gy of TBI twice a day for 4 days. Pretreatment blood samples were obtained 1 to 10 days prior to the first fraction of TBI. Additional blood samples were drawn at the indicated times (approximate, see Supplementary Table 2) after the first fraction. Panel B: PBMCs were isolated from whole blood samples by RBC lysis from seven patients. Protein lysates were prepared and levels of phospho-Smc1 were determined by ELISA (each lysate run in triplicate). Phospho-Smc1 levels are plotted as means ± SD. All raw ELISA data are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Panel C: Phospho-Smc1 levels (mean ± SD) as a function of time. Each point has at least six samples except the point for 56 h, where only five samples were available.

Induction of Phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and Phospho-Smc1Ser-966 in Circulating Cells after Therapeutic Exposure of Humans to Ionizing Radiation

We next determined whether the observed radiation-induced phosphorylation of Smc1 was an artifact of in vitro or ex vivo conditions or whether it also occurred in vivo. After informed consent was obtained, blood was collected by phlebotomy from 15 cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy. Where possible, complete and differential blood counts were obtained from patients within 14 days of their radiotherapy (Supplementary Table 2); these data confirmed that none of the patients had a significant burden of tumor cells in the circulation. Three types of exposure were investigated: TBI (n = 9), partial-body irradiation (n = 5), and internal exposure to a radioisotope (131I) (n = 1). A summary of the patients enrolled in the study and additional clinical and demographic data are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Seven patients received TBI as part of their conditioning regimen for cell transplantation therapy. These patients received 1.5-Gy fractions twice daily for four days (Fig. 4A). Pretreatment blood samples were obtained an average of 5 days (range 1 to 15 days) prior to the first fraction. Post-treatment blood samples were drawn at multiple times (approximately 2, 8, 32, 56 and 80 h) after the first fraction; note that the later blood draws occurred after additional fractions of radiation had been delivered (Fig. 4A). PBMCs were isolated from whole blood samples by RBC lysis and analyzed by our phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 ELISA. As shown in Fig. 4B (see also Supplementary Table 1), all patients showed significant induction of both phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 in their circulating cells after therapeutic radiation exposures. The average induction levels across all patients at 2 h after exposure were 23-fold for phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and 34-fold for phospho-Smc1Ser-966. These levels of induction in vivo are comparable (i.e., within a factor of two- to threefold) to those observed in primary human PBMCs after irradiation (Fig. 3B). As seen in Fig. 4C, overall there was a slight increase in the mean phospho-Smc1 levels across all patients after additional doses of radiation. The small increase in phospho-Smc1 signal is likely due to the time between the deliveries of successive radiation fractions, during which the phospho-Smc1 signal goes down (for example, compare 2 and 8 h in Fig. 4C).

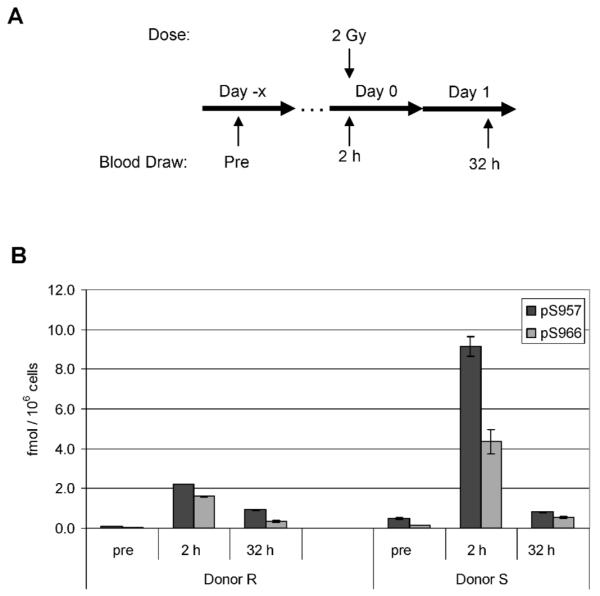

In the seven TBI patients presented in Fig. 4, the kinetics of the phospho-Smc1 response is complicated by the delivery of multiple fractions of radiation and the timing of sample collection. In contrast, two additional patients received a single fraction of 2 Gy, allowing us to determine the persistence of phospho-Smc1 induction after a single exposure (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5B, both phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 showed significant induction at 2 h postirradiation. Furthermore, despite no additional exposure to radiation, both phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 remained elevated at 32 h postirradiation (tenfold and twofold for one donor and fivefold and fourfold for the second donor). Although the response of donor S was significantly greater than that of donor R at 2 h (Fig. 5B), the residual induction of phospho-Smc1 was similar in the two patients at 32 h. Although further studies are warranted, it is interesting to speculate that interindividual differences in inherent radiosensitivity might be most apparent early in the kinetics of activation of the DNA damage response (see also Supplementary Fig. S3A).

FIG. 5.

Phospho-Smc1 levels in human PBMCs isolated from two patients after 2 Gy total-body irradiation. Panel A: Diagram of the treatment regimen for two patients undergoing conditioning for autologous transplantation. The patients received a single 2-Gy dose of TBI. Blood samples were drawn before treatment and at approximately 2 and 32 h after TBI. Panel B: Protein lysates were prepared from PBMCs isolated from whole blood by RBC lysis. Protein lysates were evaluated for levels of phospho-Smc1 by ELISA with each lysate run in triplicate. Phospho-Smc1 levels are plotted as means ± SD. All raw ELISA data are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

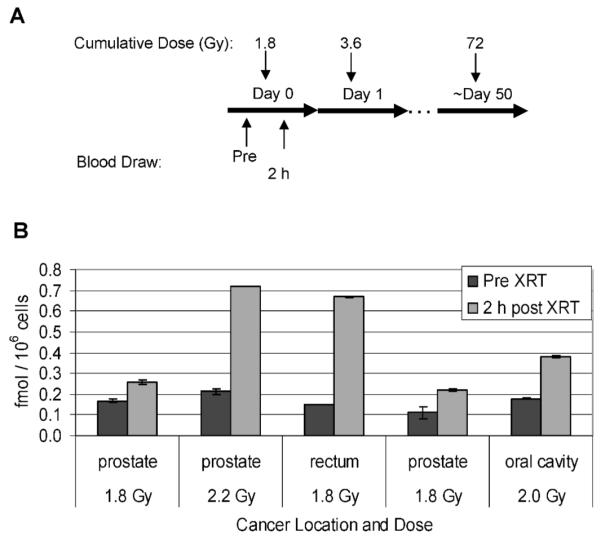

Five patients received partial-body irradiation as part of their treatment regimen for solid tumors of either the prostate, rectum or oral cavity (Supplementary Table 2). All five patients received a single fraction (ranging from 1.8–2.23 Gy) of radiation each day for a total of 25–35 fractions. Pretreatment blood samples were obtained immediately prior to the first fraction, and a second blood sample was obtained approximately 2 h after the first fraction had been delivered. PBMCs were isolated from whole blood samples by RBC lysis and analyzed by the phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 ELISAs. As shown in Fig. 6, all five patients showed significant induction of phospho-Smc1Ser-957, with an average induction across all five patients of 2.6-fold. This was significantly less than the induction level seen after TBI (24-fold), likely due to the more restricted radiation field compared to that for the TBI patients. Additionally, the induction level varied significantly among the patients (ranging from 2.0- to 4.5-fold induction), likely due to a combination of interindividual variation as well as differences among patients in the volume of tissue irradiated and the blood flow through the treatment field.

FIG. 6.

Phospho-Smc1(pS957) levels in human PBMCs isolated from patients undergoing partial-body irradiation for treatment of solid tumors. Panel A: Diagram of the treatment regimen for patients undergoing radiation therapy for solid tumors. Pretreatment blood samples were obtained just prior to and approximately 2 h after the first 1.8-Gy fraction. Panel B: PBMCs were isolated from whole blood samples from four patients by RBC lysis. Levels of phospho-Smc1 were determined by ELISA (each lysate run in triplicate) and plotted as means ± SD. All raw ELISA data are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

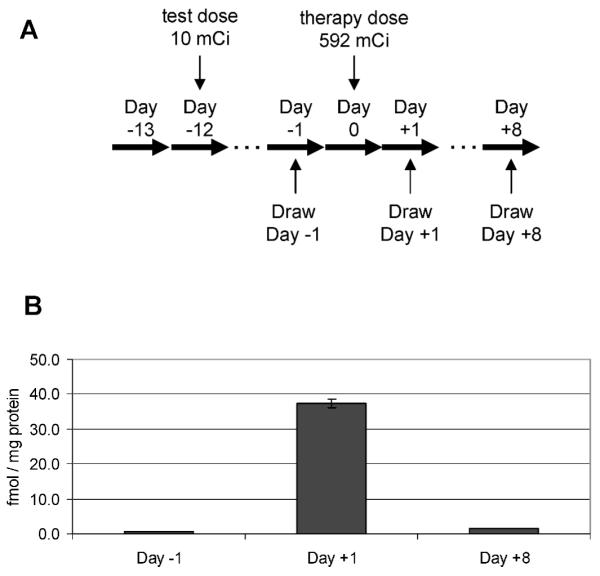

One patient received radioimmunotherapy with 131I-Tositumomab for treatment of a large B-cell lymphoma, providing an opportunity to determine the responsiveness of phospho-Smc1 to internal contamination with a radioisotope. As shown schematically in Fig. 7A, blood samples were obtained from the patient on day −1, day +1 (1 day after receiving a therapeutic dose of 592 mCi of 131I-Tositumomab), and day +8. Twenty-three hours after the administration of the therapy dose, there was a 49-fold induction of phospho-Smc1Ser-957 relative to the pretherapy level (Fig. 7B). At day +8, phospho-Smc1 induction had decreased to 1.9-fold. The high level of phospho-Smc1Ser-957 in the circulating blood cells 23 h after the initial exposure is probably the result of the continuous activation of the DDR in response to the injected radioisotope.

FIG. 7.

Phospho-Smc1(pS957) levels in human PBMCs isolated from a patient undergoing radioimmunotherapy with 131I-Tositumomab for large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Panel A: Diagram of the treatment regimen. Panel B: PBMCs were isolated from whole blood samples by RBC lysis at the indicated times. Protein lysates were prepared, and levels of phospho-Smc1 were determined by ELISA (each lysate run in duplicate). Because the day +1 sample was radioactive, accurate cell counts were not obtained, so the data were normalized to total protein concentration. The mean phospho-Smc1 levels are plotted with error bars representing the range of measurements. All raw ELISA data are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and Phospho-Smc1Ser-966 ELISA Assays Reveal Comparable Radiation-Induced Responses in Immortalized and Primary Human Cells, as Well as in Cells Exposed In Vivo and In Vitro

The phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 ELISAs developed in this study provide an assessment of the activation level of the ATM-dependent DDR in human cells. Our data demonstrate comparable responses (within twofold) between immortalized lymphoblasts and primary human PBMCs (compare Figs. 2 and 3B) and nearly identical responses between genetically identical cycling and quiescent human PBMCs (compare Figs. 3A and B). Furthermore, the corresponding responses are observed in vivo (Figs. 4-7), confirming the physiological relevance of these phosphorylations in humans. These assays have potential applications for basic research studies and for diagnosing radiation exposure in humans, as discussed below.

Measuring the Activity of the DNA Damage Response for Research Studies

Activity of the DDR network has typically been assessed by Western blot analysis or by the enumeration of DNA damage-induced nuclear foci (28, 29) by either fluorescence microscopy (30) or flow cytometry (31, 32). Western blotting is cumbersome and semi-quantitative at best and ideally requires recombinant protein run at multiple dilutions to serve as a quantification standard (33). Expression and purification of recombinant protein is expensive and time-consuming, and the number of samples that can be analyzed per blot is limited by gel size and the number of lanes required for size markers and quantification standards. Automated fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry assays are limited due to the constraint of overlapping foci and the time-dependent change in focus size (32, 34).

Although commercially available ELISAs have been developed for a handful of DDR network members, none is available for detection of phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966. We have developed two sandwich ELISAs that are capable of detecting the phosphorylation of Smc1 at S957 and S966. The two assays use a common monoclonal capture antibody but unique monoclonal antibodies to the two different phosphorylated serines. Both assays use novel phospho-peptide quantification standards, eliminating the cost and difficulties associated with the expression, phosphorylation and purification of recombinant protein standards. These assays provide a potential high throughput and quantitative alternative to Western blot analysis of phospho-Smc1 as a readout of activation of the DNA damage response.

Potential Use of the Phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and Phospho-Smc1Ser-966 ELISA Assays for Diagnosing Radiation Exposure in Humans

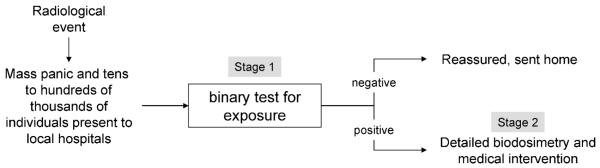

Media coverage of actual and potential nuclear attacks or accidents has left the public with a sensationalized fear of such events, focused on catastrophic outcomes. Our disaster management system must plan for mass panic in the event of a radiological event; otherwise, emergency facilities are likely to be overwhelmed by masses of panicked people asking to be evaluated for exposure and interfering with triage and treatment of those whose lives are imminently in danger (35, 36). In the face of mass panic, effective emergency management of a nuclear or radiological event will require diagnostics for initial triage of the panicked masses as well as for detailed biodosimetry to guide appropriate dose-dependent intervention (Fig. 8). Initial triage (stage 1 triage) is critical to reduce the burden on the healthcare system and conserve precious resources for treatment of individuals acutely at risk. Any diagnostic used for initial triage must be amenable to emergency use on large numbers of panicked people. The sheer number of people to be screened will necessitate ease of use, no need for specialized equipment, little or no training required to administer, little (or no) technician time required, and near-immediate results. For example, one might envision use of a self-administered, lateral flow-based test strip format that could provide a binary distinction between exposed and not exposed.

FIG. 8.

Hypothetical staged triage of large numbers of individuals presenting for evaluation of exposure after a radiological event. In the first round of triage, a binary test could be used to distinguish exposed from unexposed individuals.

After initial triage of victims exposed to ionizing radiation, quantitative biodosimetry (stage 2 triage) is important because moderate exposure to ionizing radiation (<10 Gy) can be survived with dose-appropriate medical intervention (1, 37-39). For example, the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) Radiation Working Group recommends dividing patients into four major treatment categories: normal care (1–3 Gy), critical care (3–5 Gy), intensive care (5–10 Gy), and expectant care (≥10 Gy) (1). A more recent report recommended specific therapeutic guidelines for antibiotics, cytokines and transplantation in the event of a radiological event (40); patients exposed to <2 Gy would receive antibiotics, and patients exposed to <3 Gy would receive cytokine support. Transplantation would be reserved for patients exposed to 7–10 Gy (40). Hence, unlike stage 1 triage, during which a binary distinction between exposed and unexposed would be sufficient, stage 2 triage will require quantitative determination of exposure.

Our data demonstrate that phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 show promise as targets for development of a diagnostic test to detect human radiation exposure. First, both phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 are rapidly induced in human cells, as early as 15 min after exposure to radiation (data not shown). Second, the induction of these phospho-targets is robust in the clinically relevant dose range of 1–12 Gy. Third, the induction of these phospho-targets is not limited to cycling cells, since quiescent human PBMCs also show a robust response. Fourth, the response is physiologically relevant (i.e., not an artifact of in vitro conditions or immortalization), since it is observed both in primary human cells in culture and in circulating cells obtained from patients after therapeutic exposure to ionizing radiation. Fifth, the induction of these phospho-targets occurs after a variety of exposure types, including TBI, partial-body irradiation and internal contamination with radioisotope. Sixth, the ELISA platform we developed to measure the induction of these phospho-targets is widely used in clinical laboratories, and thus the infrastructure and expertise already exist for implementing these assays in clinical laboratories.

Significant additional clinical validation will be needed before the phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 assays can be deployed as diagnostics. For example, it will be imperative to minimize false positives to avoid causing more panic in an emergency situation, so it is imperative to explore whether conditions other than radiation exposure (e.g., smoking, stress, diagnostic imaging procedures, or chemotherapy) might activate the DNA damage response sufficiently to produce a positive test result in the assays. Additionally, it will be important to characterize biological variability of the phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 radiation-induced responses, including both inter- and intraindividual variation (discussed below).

Finally, it will be important to further characterize the kinetics of the in vivo phospho-Smc1 response after radiation exposure. Both our in vivo and in vitro experiments demonstrate that phospho-Smc1 levels reach a maximum at approximately 2 h after exposure (Figs. 2, 3, 5). Although this rapid accumulation is followed by a rapid decline in phospho-Smc1 levels over the next 8 h, we noted a long tail in the kinetic curves, with both phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 remaining significantly elevated above baseline at much later times. For the time courses examined in these studies (as long as 48 h postirradiation), we did not observe a return to baseline levels for phospho-Smc1. For example, in the patients described in Fig. 5, where a single total-body fraction was delivered, the latest time we were able to sample was 32 h, at which point both phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and phospho-Smc1Ser-966 remained significantly elevated (tenfold and twofold for one donor and fivefold and fourfold for the second donor). These ELISAs (in a lateral flow “test strip” format) could easily be stockpiled and rapidly deployed in large urban centers, allowing local municipalities to begin the triage process immediately during the national mobilization in the ensuing days after a disaster. This not only would help alleviate the immediate mass panic at the local level but also would jump start the biodosimetry phase of the national response by identifying the exposed individuals in stage 1 while the infrastructure was established for more detailed biodosimetry to be performed as part of the second stage of triage.

Potential Use of the Phospho-Smc1Ser-957 and Phospho-Smc1Ser-966 ELISAS for Studying Interindividual Differences in Inherent Radiosensitivity

The DNA damage response pathway is known to play a key role in cancer, aging and neurodegenerative disease, and it is increasingly becoming a focus of possible treatment strategies (42). Although there has been significant progress in the mechanistic understanding of DNA damage response processes, few studies have bridged the gap between basic research and application to population studies. Unfortunately, population studies of DNA repair capacity have been hindered by the lack of practical, quantitative tools for measuring the DNA damage response in clinical or epidemiological studies. This unmet need was highlighted at a joint NIH workshop for the Working Group on Integrated Translational Research in DNA Repair (43). The phospho-Smc1 ELISAs described in this study hold great promise for clinical and epidemiological studies aimed at characterizing interindividual differences in the cellular DDR and relating these differences to clinically relevant end points such as risk for developing cancer or susceptibility to high-grade toxicity from therapies that induce DNA damage (e.g. radiation therapy, clastogenic chemotherapy).

Smc1 is a particularly attractive target for studying interindividual differences in the DNA damage response. First, Smc1 is the most downstream component of the known ATM-NBS1-BRCA1 signaling pathway, and hence the phosphorylation of Smc1 is dependent on the successful completion of multiple upstream steps in activation of this pathway (26). As a result, phospho-Smc1 has the potential to integrate the functional activity of multiple components of the ATM pathway (26), providing fertile grounds for detecting human variations in the DNA damage response. Second, phospho-Smc1 is induced in response to a wide array of DNA-damaging agents (27, 44, 45), and hence its activation is likely to be a general readout of pathway activity. Third, Smc1 phosphorylation is specifically critical for cell survival and maintenance of optimal chromosomal stability after DNA damage, because it is the only target of ATM in which mutation of the phosphorylation sites affects cellular radiosensitivity (23, 44). Fourth, despite its critical role in the DDR, there is tremendous human variation in the phosphorylation of Smc1 in response to DNA damage. For example, cells from patients afflicted with the genetic disorder AT are severely defective in Smc1 phosphorylation in response to ionizing radiation due to a lack of Atmp kinase activity (Fig. 2C) (27). In fact, a recently published flow cytometry-based assay for measuring the phosphorylation of Smc1 in response to ionizing radiation or bleomycin shows that carriers of mutations in the ATM gene can be detected using this cell-based assay (46).

Our data demonstrate that the phospho-Smc1 ELISAs are able to distinguish ATM+ from ATM− cells (Fig. 2C). An ANOVA-based analysis of interindividual variation in the phospho-Smc1 response in our healthy blood donors (Supplementary Fig. 3A) showed evidence of significant interindividual differences as well. Although much larger studies will be required to draw conclusions about the utility of our assay for assessing interindividual variation, this is an interesting area of future study.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. 1. Screening of rabbit sera and hybridoma supernatants for anti-Smc1 antibodies. Panel A: Rabbit sera were screened against protein lysates isolated 2 h after lymphoblasts were treated with 0 or 10 Gy of ionizing radiation. Lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and evaluated by Western blotting using Protein-A purified antibodies from preimmune (pre) or postimmune (post) rabbit sera. Commercial antibodies to p-Smc1(pS957) and total Smc1 (pan) were included as positive controls. Panel B: Hybridoma supernatants were screened by immunoprecipitation. Antibodies purified from hybridoma supernatants by protein-A affinity columns were used to immunoprecipitate Smc1 from protein lysates generated 2 h after lymphoblasts were treated with 0 or 10 Gy of ionizing radiation. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and evaluated by Western blotting using commercial antibodies to p-Smc1(pS957) and total (pan) Smc1. Input lysates, without immunoprecipitation, were run as a positive controls. Supplementary Fig. 2. Agreement between ELISA and Western blotting for detecting induction of phospho-Smc1. Protein lysates were generated from GM07057 cells at the indicated times after mock irradiation (0 h) or exposure to 2 Gy. Lysates were evaluated for Smc1 phosphorylation at pS957 and pS966 by either ELISA or Western blotting. Panel A: For ELISA, each lysate was run in triplicate. The mean concentrations of p-Smc1 (pS957) and p-Smc1 (pS966) were calculated from the standard peptide curve, and the values were normalized to cell count. The error bars are ± SD. Panel B: For Western blot analysis, 10 μg of each lysate was resolved by SDS-PAGE. The anti-Smc1 capture antibody (FHC37F) was used to evaluate total Smc1 levels, while the two detection antibodies (FHC37Cp and FHC37Dp) were used to evaluate the levels of phospho-Smc1S957 and phospho-Smc1S966. Supplementary Fig. 3. Technical and biological variation for cultured human PBMCs from two donors (analysis of data from Fig. 4A). We performed an ANOVA analysis to characterize the technical and biological variation for each (dose, time) experiment separately. For a given (dose, time) setting, Yijk denotes the array measurement of the kth technical replicate of the jth blood draw of the ith donor, where k = 1,…, nij; j = 1,…, m; i = 1,…,r For the in vitro experiment, we have r = 2, m = 3, nif = 2–3. We employed a mixed effect model: Yijk = u + αi + βij + εijk, where u is the population mean; αi ~ N(0, σ2α) represents the individual effect; βij ~ N(0, σ2β) represents the blood draw effect; and εijk ~ N(0, σ2) represents the measurement errors in technical replicates. The estimated technical variation (σ), within subject variation (σβ) and between subject variation (σα) are shown for pS957 (panel A) and pS966 (panel B). The results indicate that interindividual variation is substantial for pS957, dwarfing the assay and intraindividual variation. Further studies with larger numbers of donors will be needed to verify this preliminary finding. http://dx.doi/10.1667/RR2402.1.S1

Supplementary Table 1. Raw ELISA data for figures. http://dx.doi/10.1667/RR2402.1.S2

Supplementary Table 2. Summary of information on the patients enrolled in the study, including clinical and demographic data. http://dx.doi/10.1667/RR2402.1.S3

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH U19 AI067770, which funds the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/University of Washington Center for Medical Countermeasures Against Radiation “Radiation Dose-Dependent Interventions” (http://depts.washington.edu/cmcr/). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Waselenko JK, MacVittie TJ, Blakely WF, Pesik N, Wiley AL, Dickerson WE, Tsu H, Confer DL, Coleman CN, Dainiak N. Medical management of the acute radiation syndrome: Recommendations of the strategic national stockpile radiation working group. Ann. Intern. Med. 2004;140:1037–1051. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-12-200406150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grayson JM, Harrington LE, Lanier JG, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Differential sensitivity of naive and memory CD8+ Tcells to apoptosis in vivo. J. Immunol. 2002;169:3760–3770. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui YF, Gao YB, Yang H, Xiong CQ, Xia GW, Wang DW. Apoptosis of circulating lymphocytes induced by whole body gamma-irradiation and its mechanism. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 1999;18:185–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grace MB, Muderhwa JM, Salter CA, Blakely WF. Use of a centrifuge-based automated blood cell counter for radiation dose assessment. Mil. Med. 2006;171:908–912. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.9.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goans RE, Holloway EC, Berger ME, Ricks RC. Early dose assessment following severe radiation accidents. Health Phys. 1997;72:513–518. doi: 10.1097/00004032-199704000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker DD, Parker JC. Estimating radiation dose from time to emesis and lymphocyte depletion. Health Phys. 2007;93:701–704. doi: 10.1097/01.HP.0000275289.45882.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demidenko E, Williams BB, Swartz HM. Radiation dose prediction using data on time to emesis in the case of nuclear terrorism. Radiat. Res. 2009;171:310–319. doi: 10.1667/RR1552.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amundson SA, Fornace AJ., Jr. Gene expression profiles for monitoring radiation exposure. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 2001;97:11–16. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amundson SA, Bittner M, Meltzer P, Trent J, Fornace AJ., Jr. Induction of gene expression as a monitor of exposure to ionizing radiation. Radiat. Res. 2001;156:657–661. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0657:iogeaa]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amundson SA, Bittner M, Meltzer P, Trent J, Fornace AJ., Jr. Biological indicators for the identification of ionizing radiation exposure in humans. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2001;1:211–219. doi: 10.1586/14737159.1.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amundson SA, Fornace AJ., Jr. Monitoring human radiation exposure by gene expression profiling: Possibilities and pitfalls. Health Phys. 2003;85:36–42. doi: 10.1097/00004032-200307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amundson SA, Grace MB, McLeland CB, Epperly MW, Yeager A, Zhan Q, Greenberger JS, Fornace AJ., Jr. Human in vivo radiation-induced biomarkers: Gene expression changes in radiotherapy patients. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6368–6371. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akerman GS, Rosenzweig BA, Domon OE, Tsai CA, Bishop ME, McGarrity LJ, Macgregor JT, Sistare FD, Chen JJ, Morris SM. Alterations in gene expression profiles and the DNA-damage response in ionizing radiation-exposed TK6 cells. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2005;45:188–205. doi: 10.1002/em.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchetti F, Coleman MA, Jones IM, Wyrobek AJ. Candidate protein biodosimeters of human exposure to ionizing radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2006;82:605–639. doi: 10.1080/09553000600930103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivey RG, Subramanian O, Lorentzen TD, Paulovich AG. Antibody-based screen for ionizing radiation-dependent changes in the mammalian proteome for use in biodosimetry. Radiat. Res. 2009;171:549–561. doi: 10.1667/RR1638.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desai N, Wu H, George K, Gonda SR, Cucinotta FA. Simultaneous measurement of multiple radiation-induced protein expression profiles using the Luminex™ system. Adv. Space Res. 2004;34:1362–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.asr.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyburski JB, Patterson AD, Krausz KW, Slavik J, Fornace AJ, Jr., Gonzalez FJ, Idle JR. Radiation metabolomics. 1. Identification of minimally invasive urine biomarkers for gamma-radiation exposure in mice. Radiat. Res. 2008;170:1–14. doi: 10.1667/RR1265.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tyburski JB, Patterson AD, Krausz KW, Slavik J, Fornace AJ, Jr., Gonzalez FJ, Idle JR. Radiation metabolomics. 2. Dose- and time-dependent urinary excretion of deaminated purines and pyrimidines after sublethal gamma-radiation exposure in mice. Radiat. Res. 2009;172:42–57. doi: 10.1667/RR1703.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swartz HM, Burke G, Coey M, Demidenko E, Dong R, Grinberg O, Hilton J, Iwasaki A, Lesniewski P, Schauer DA. In vivo EPR for dosimetry. Radiat. Meas. 2007;42:1075–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.radmeas.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watrin E, Peters JM. Cohesin and DNA damage repair. Exp. Cell Res. 2006;312:2687–2693. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watrin E, Peters JM. The cohesin complex is required for the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 2009;28:2625–2635. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stursberg S, Riwar B, Jessberger R. Cloning and characterization of mammalian SMC1 and SMC3 genes and proteins, components of the DNA recombination complexes RC-1. Gene. 1999;228:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim ST, Xu B, Kastan MB. Involvement of the cohesin protein, Smc1, in atm-dependent and independent responses to DNA damage. Genes Dev. 2002;16:560–570. doi: 10.1101/gad.970602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauerschmidt C, Arrichiello C, Burdak-Rothkamm S, Woodcock M, Hill MA, Stevens DL, Rothkamm K. Cohesin promotes the repair of ionizing radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks in replicated chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:477–487. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitagawa R, Bakkenist CJ, McKinnon PJ, Kastan MB. Phosphorylation of SMC1 is a critical downstream event in the ATM-NBS1-BRCA1 pathway. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1423–1438. doi: 10.1101/gad.1200304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitagawa R, Kastan MB. The ATM-dependent DNA damage signaling pathway. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2005;70:99–109. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yazdi PT, Wang Y, Zhao S, Patel N, Lee EY, Qin J. SMC1 is a downstream effector in the ATM/NBS1 branch of the human S-phase checkpoint. Genes Dev. 2002;16:571–582. doi: 10.1101/gad.970702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Veelen LR, Essers J, van de Rakt MW, Odijk H, Pastink A, Zdzienicka MZ, Paulusma CC, Kanaar R. Ionizing radiation-induced foci formation of mammalian Rad51 and Rad54 depends on the Rad51 paralogs, but not on Rad52. Mutat. Res. 2005;574:34–49. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sedelnikova OA, Rogakou EP, Panyutin IG, Bonner WM. Quantitative detection of 125IdU-induced DNA double-strand breaks with gamma-H2AX antibody. Radiat. Res. 2002;158:486–492. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2002)158[0486:qdoiid]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roch-Lefevre S, Mandina T, Voisin P, Gaetan G, Mesa JE, Valente M, Bonnesoeur P, Garcia O, Voisin P, Roy L. Quantification of gamma-H2AX foci in human lymphocytes: A method for biological dosimetry after ionizing radiation exposure. Radiat. Res. 2010;174:185–194. doi: 10.1667/RR1775.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka T, Huang X, Halicka HD, Zhao H, Traganos F, Albino AP, Dai W, Darzynkiewicz Z. Cytometry of ATM activation and histone H2AX phosphorylation to estimate extent of DNA damage induced by exogenous agents. Cytometry A. 2007;71:648–661. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothkamm K, Horn S. Gamma-H2AX as protein biomarker for radiation exposure. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita. 2009;45:265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dickinson J, Fowler SJ. Quantification of proteins on Western blots using ECL. In: Walker JM, editor. The Protein Protocols Handbook. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: 2002. pp. 429–438. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerashchenko BI, Dynlacht JR. A tool for enhancement and scoring of DNA repair foci. Cytometry A. 2009;75:245–252. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ketchum LE. Lessons of Chernobyl: SNM members try to decontaminate world threatened by fallout. part II. J. Nucl. Med. 1987;28:933–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsu EB, Casani JA, Romanosky A, Millin MG, Singleton CM, Donohue J, Feroli ER, Rubin M, Subbarao I, Kelen GD. Are regional hospital pharmacies prepared for public health emergencies? Biosecur. Bioterr. 2006;4:237–243. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2006.4.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dainiak N, Ricks RC. The evolving role of haematopoietic cell transplantation in radiation injury: Potentials and limitations. Br. J. Radiol. Suppl. 2005;27:169–174. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dainiak N. Hematologic consequences of exposure to ionizing radiation. Exp. Hematol. 2002;30:513–528. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alpen E. Radiation Biophysics. Academic Press; San Diego: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weisdorf D, Chao N, Waselenko JK, Dainiak N, Armitage JO, McNiece I, Confer D. Acute radiation injury: Contingency planning for triage, supportive care, and transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:672–682. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Posthuma-Trumpie GA, Korf J, van Amerongen A. Lateral flow (immuno)assay: Its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. A literature survey. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009;393:569–582. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alberts B. Redefining cancer research. Science. 2009;325:1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1181224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinlib L, Friedberg EC, Working Group on Integrated Translational Research in DNA Repair Report of the working group on integrated translational research in DNA repair. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2007;6:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kitagawa R, Bakkenist CJ, McKinnon PJ, Kastan MB. Phosphorylation of SMC1 is a critical downstream event in the ATM-NBS1-BRCA1 pathway. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1423–1438. doi: 10.1101/gad.1200304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garg R, Callens S, Lim DS, Canman CE, Kastan MB, Xu B. Chromatin association of rad17 is required for an ataxia telangiectasia and rad-related kinase-mediated S-phase checkpoint in response to low-dose ultraviolet radiation. Mol. Cancer Res. 2004;2:362–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nahas SA, Butch AW, Du L, Gatti RA. Rapid flow cytometry-based structural maintenance of chromosomes 1 (SMC1) phosphorylation assay for identification of ataxia-telangiectasia homozygotes and heterozygotes. Clin. Chem. 2009;55:463–472. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.107128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1. Screening of rabbit sera and hybridoma supernatants for anti-Smc1 antibodies. Panel A: Rabbit sera were screened against protein lysates isolated 2 h after lymphoblasts were treated with 0 or 10 Gy of ionizing radiation. Lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and evaluated by Western blotting using Protein-A purified antibodies from preimmune (pre) or postimmune (post) rabbit sera. Commercial antibodies to p-Smc1(pS957) and total Smc1 (pan) were included as positive controls. Panel B: Hybridoma supernatants were screened by immunoprecipitation. Antibodies purified from hybridoma supernatants by protein-A affinity columns were used to immunoprecipitate Smc1 from protein lysates generated 2 h after lymphoblasts were treated with 0 or 10 Gy of ionizing radiation. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and evaluated by Western blotting using commercial antibodies to p-Smc1(pS957) and total (pan) Smc1. Input lysates, without immunoprecipitation, were run as a positive controls. Supplementary Fig. 2. Agreement between ELISA and Western blotting for detecting induction of phospho-Smc1. Protein lysates were generated from GM07057 cells at the indicated times after mock irradiation (0 h) or exposure to 2 Gy. Lysates were evaluated for Smc1 phosphorylation at pS957 and pS966 by either ELISA or Western blotting. Panel A: For ELISA, each lysate was run in triplicate. The mean concentrations of p-Smc1 (pS957) and p-Smc1 (pS966) were calculated from the standard peptide curve, and the values were normalized to cell count. The error bars are ± SD. Panel B: For Western blot analysis, 10 μg of each lysate was resolved by SDS-PAGE. The anti-Smc1 capture antibody (FHC37F) was used to evaluate total Smc1 levels, while the two detection antibodies (FHC37Cp and FHC37Dp) were used to evaluate the levels of phospho-Smc1S957 and phospho-Smc1S966. Supplementary Fig. 3. Technical and biological variation for cultured human PBMCs from two donors (analysis of data from Fig. 4A). We performed an ANOVA analysis to characterize the technical and biological variation for each (dose, time) experiment separately. For a given (dose, time) setting, Yijk denotes the array measurement of the kth technical replicate of the jth blood draw of the ith donor, where k = 1,…, nij; j = 1,…, m; i = 1,…,r For the in vitro experiment, we have r = 2, m = 3, nif = 2–3. We employed a mixed effect model: Yijk = u + αi + βij + εijk, where u is the population mean; αi ~ N(0, σ2α) represents the individual effect; βij ~ N(0, σ2β) represents the blood draw effect; and εijk ~ N(0, σ2) represents the measurement errors in technical replicates. The estimated technical variation (σ), within subject variation (σβ) and between subject variation (σα) are shown for pS957 (panel A) and pS966 (panel B). The results indicate that interindividual variation is substantial for pS957, dwarfing the assay and intraindividual variation. Further studies with larger numbers of donors will be needed to verify this preliminary finding. http://dx.doi/10.1667/RR2402.1.S1