Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the association of female caregivers’ oral health literacy with their knowledge, behaviors, and the reported oral health status of their young children. Data on caregivers’ literacy, knowledge, behaviors, and children’s oral health status were used from structured interviews with 1158 caregiver/child dyads from a low-income population. Literacy was measured with REALD-30. Caregivers’ and children’s median ages were 25 yrs (range = 17-65) and 15 mos (range = 1-59), respectively. The mean literacy score was 15.8 (SD = 5.3; range = 1-30). Adjusted for age, education, and number of children, low literacy scores (< 13 REALD-30) were associated with decreased knowledge (OR = 1.86; 95% CI = 1.41, 2.45) and poorer reported oral health status (OR = 1.44; 95% CI = 1.02, 2.05). Lower caregiver literacy was associated with deleterious oral health behaviors, including nighttime bottle use and no daily brushing/cleaning. Caregiver oral health literacy has a multidimensional impact on reported oral health outcomes in infants and young children.

Keywords: oral health literacy, infant oral health, early childhood caries, oral health knowledge, oral health outcomes in young children

Introduction

Despite advances in caries prevention over the past several decades, analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) indicates that the prevalence of caries in children ages 2 to 4 yrs increased from 18% in 1988-94 to 24% in 1999-04 (Tomar and Reeves, 2009). Changes in biological or proximal early childhood caries (ECC) risk factors (Tinanoff et al., 2002; Harris et al., 2004) cannot fully explain this phenomenon. Rather, demographic changes in tandem with emerging and re-emerging distal risk factors or determinants, such as being of minority racial status and certain family characteristics, appear to be a major driving force behind these current trends (Amstutz and Rozier, 1995; Patrick et al., 2006; Edelstein and Chinn, 2009). Another potential determinant that has yet to be investigated is health literacy.

Health literacy is now recognized as an important component of health care (Nielsen-Bohlman et al., 2004). Based on a nationally representative sample, Yin and co-workers reported that nearly 30% of US parents have difficulty understanding and utilizing health information (Yin et al., 2009). Systematic reviews in medicine have confirmed that low literacy is associated with adverse health outcomes such as poor knowledge, morbidity measures, general health status, and the use of health resources (Andrus and Roth, 2002; DeWalt et al., 2004). Two recent comprehensive reviews were conclusive in linking low parental health literacy and deleterious health behaviors that affect child health (Sanders et al., 2009a) and child health outcomes (DeWalt and Hink, 2009).

Most studies have found a direct association between caregiver health literacy and knowledge (DeWalt et al., 2004). In dentistry, caregivers’ infant and early childhood oral health knowledge is of paramount importance, because oral health behaviors are the exclusive domain of the caregiver during the early years of life. In “Oral Health in America,” the Surgeon General stressed that if parents are unfamiliar with the importance and care of their child’s primary teeth, they are unlikely to take the appropriate action that may prevent ECC or may fail to seek professional services (USDHHS, 2000). In short, there are reasons to hypothesize that caregivers’ oral health literacy would be related to their oral health knowledge, behaviors, and the oral health status of their pre-school-aged children. Accordingly, the aim of the present study was to investigate these associations.

Materials & Methods

The study relied upon interview data from 1273 child/caregiver dyads participating in the Carolina Oral Health Literacy (COHL) project (Lee et al., 2010). All caregivers and children were enrolled in the Women, Infants and Children’s Supplemental Nutrition Program (WIC).

Caregivers’ demographic information included age, race, education, and number of children. Age was measured in years and coded as a quintile-categorical indicator variable, because of its non-normal distribution. Race was self-reported as White, African American, or American Indian. Education was coded as a 4-level categorical variable, with 1 = less than high school, 2 = high school/GED, 3 = some technical education or college, 4 = college degree/higher. Number of children was coded as a 4-level categorical variable, with 1 = 1 child, 2 = 2 children, 3 = 3 children, and 4 = 4 or more children. Child demographic data included gender, age, and birth order.

Oral health literacy was measured by means of a validated word recognition test, the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Dentistry (REALD-30), an instrument with good convergent validity and internal consistency: Cronbach’s α = 0.87 (Lee et al., 2007). Scores range between 0 (lowest literacy) and 30 (highest literacy).

To assess oral health knowledge, we used a 6-item knowledge survey (Shick et al., 2005; Mathu-Muju et al., 2008). Caregivers were asked to answer “agree,” “disagree,” or “don’t know” to knowledge-related items such as: “Fluoride helps prevent tooth decay” and “Tooth decay in baby teeth can cause infections that can spread to the face and other parts of the body.” A knowledge score ranging from 0 to 6 was derived from the sum of correct responses. The normality assumption for literacy and knowledge scores was tested by a combined skewness and kurtosis evaluation test (D’Agostino et al., 1990) with α = 0.05.

To assess oral hygiene and high-caries-risk dietary behaviors, we relied upon a set of questionnaire items as modified from Douglass (Douglass et al., 2001). Oral hygiene was assessed with the question, “Do you brush or clean your child’s teeth or gums every day?” Dietary habits were assessed with the following items: “How often does your child drink fruit juices?”; “How often does your child receive sweet snacks?”; “Do you/have you ever put your infant/child to bed with a bottle?” Possible responses for the first two items were “never,” ‘“once a month or less,” “once a week,” “once a day,” and “more than once a day,” while “never” and “ever” were the possible answers to the third item.

Children’s oral health status was assessed by a caregiver-reported question from NHANES: “How would you describe the condition of your child’s teeth?” Response items included “excellent,” “very good,” “good,” “fair,” “poor,” “has no natural teeth,” “don’t know,” and “refuse to answer.”

To examine the distribution of demographic characteristics with literacy, knowledge, behaviors, and infant oral health status, we used descriptive tabular methods. We generated summary statistics to examine the distribution of literacy and knowledge scores by demographic characteristics and behaviors, and status classification [n, percent (%)] by child characteristics. To quantify the associations of literacy with behaviors and knowledge scores, we estimated the corresponding mean score differences and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The relationship between literacy and knowledge was assessed with Spearman’s correlation coefficient (ρ) and 95% CI, computed with bootstrapping (N = 1000 repetitions). This relationship was further examined visually for strata of infant oral health status with corresponding local polynomial smoothing functions. To determine whether deleterious behaviors were associated with poorer reported oral health status, we developed two univariate ordinal logistic regression models to obtain odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI for the association of brushing/cleaning and nighttime bottle use with status.

Two multivariate ordinal logistic regression models were developed to examine the impact of low literacy (arbitrarily defined as the lowest quintile or score < 13) on knowledge and status by obtaining OR and 95% CI. Race and education were covariates that were included a priori in the modeling. Inclusion of additional confounders (age and number of children) in the final models was determined by likelihood ratio tests, comparing nested (reduced) models with the referent (full) model, using the p < 0.1 criterion. All analyses were conducted with Stata 11.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The COHL project enrolled 1273 caregiver/child dyads. Because of small numbers in the respective categories, for this investigation we excluded male caregivers (n = 48, 3.8% of total), Asian individuals (N = 9, 0.7%), and those who did not have English as their primary language (N = 69, 5.4%). This yielded a final sample of 1158 dyads.

Demographic characteristics and behaviors are listed in Table 1. There was a 2:2:1 ratio of Whites, African Americans, and American Indians. Caregivers’ mean and median ages were 27 (SD = 7.0) and 25 yrs, respectively. Approximately 60% had a high school education or less.

Table 1.

Distribution of Infant Oral Health Knowledge and Oral Health Literacy Scores by Demographic Characteristics and Infant Oral Health Behaviors among the COHL Study Caregiver-Child Dyads (n = 1158)

| Knowledge |

Literacy |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | n | % | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 451 | 39.0 | 4.9 (1.0) | 5 | 17.4 (4.9) | 17 |

| African American | 474 | 40.9 | 4.7 (1.0) | 5 | 15.3 (5.2) | 15 |

| American Indian | 233 | 20.1 | 4.7 (1.0) | 5 | 13.7 (5.3) | 14 |

| Education | ||||||

| Did not finish high school | 276 | 23.8 | 4.6 (1.0) | 5 | 12.9 (4.9) | 13 |

| High school diploma or GED | 441 | 38.1 | 4.7 (1.0) | 5 | 15.0 (4.8) | 15 |

| Some technical or college | 382 | 33.0 | 4.9 (0.9) | 5 | 17.9 (4.6) | 18 |

| College degree or higher | 59 | 5.1 | 5.2 (0.7) | 5 | 21.0 (4.6) | 21 |

| Number of children | ||||||

| 1 | 474 | 40.9 | 4.7 (1.0) | 5 | 15.9 (5.2) | 16 |

| 2 | 368 | 31.8 | 4.8 (0.9) | 5 | 15.9 (5.0) | 16 |

| 3 | 186 | 16.1 | 4.8 (0.9) | 5 | 15.9 (5.5) | 16 |

| 4 or more | 130 | 11.2 | 4.8 (1.0) | 5 | 15.1 (5.7) | 15 |

| Age quintiles (years) | 1158 | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Q1 (range: 17.2–21.3) | 232 | 19.8 (0.9) | 4.5 (1.1) | 5 | 14.0 (4.8) | 14.5 |

| Q2 (range: 21.3–23.8) | 232 | 22.5 (0.7) | 4.7 (1.0) | 5 | 15.5 (5.1) | 15 |

| Q3 (range: 23.8–27.0) | 231 | 25.3 (0.9) | 4.8 (0.9) | 5 | 16.4 (4.8) | 16 |

| Q4 (range: 27.0–31.5) | 232 | 29.1 (1.3) | 4.9 (0.9) | 5 | 16.5 (4.9) | 17 |

| Q5 (range: 31.5–65.6) | 231 | 38.3 (6.0) | 4.9 (0.8) | 5 | 16.4 (6.1) | 16 |

| Infant oral health behaviors | ||||||

| Daily brushing/cleaning | ||||||

| No | 93 | 11.9 | 4.7 (1.1) | 5 | 14.8 (5.6) | 15 |

| Yes | 686 | 88.1 | 4.8 (1.0) | 5 | 16.0 (5.3) | 16 |

| Missing (edentulous) | 379 | |||||

| Have put the child in bed with bottle | ||||||

| Never | 808 | 69.8 | 4.8 (1.0) | 5 | 16.2 (5.3) | 16 |

| Ever | 350 | 30.2 | 4.7 (1.0) | 5 | 14.9 (5.2) | 15 |

| Frequency of juice consumption | ||||||

| Never | 316 | 27.3 | 4.8 (1.0) | 5 | 16.0 (5.2) | 16.5 |

| Occasionally | 242 | 20.9 | 4.8 (1.0) | 5 | 15.1 (5.1) | 15 |

| Once a day | 276 | 23.8 | 4.8 (0.9) | 5 | 16.6 (5.4) | 17 |

| More than once a day | 324 | 28.0 | 4.7 (1.0) | 5 | 15.4 (5.4) | 15 |

| Frequency of sweet snacks consumption | ||||||

| Never | 482 | 41.6 | 4.7 (1.0) | 5 | 15.8 (5.2) | 16 |

| Occasionally | 440 | 38.0 | 4.7 (1.0) | 5 | 15.7 (5.3) | 16 |

| Once a day | 149 | 12.9 | 4.9 (0.9) | 5 | 16.1 (5.6) | 16 |

| More than once a day | 87 | 7.5 | 4.8 (1.0) | 5 | 15.7 (5.0) | 15 |

COHL = Carolina Oral Health Literacy.

n = number of subjects in stratum.

SD = standard deviation.

Infant/child characteristics are listed in Table 2. Age distribution was median = 15, mean = 18, range = 1 to 59 mos. Eighty-two percent were in the 0 to 2 yrs age group, and 33% were edentulous. Among dentate children, the proportion of good/fair/poor status was twice as high in the 24- to 59- vs. the 6- to 23-month-old group (21 vs. 10.5%)

Table 2.

Distribution of Caregiver-reported Oral Health Status by Infant/Child Characteristics among the COHL Study Caregiver-Child Dyads (n = 1158)

| Infant Oral Health Status–n (row %) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant/Child Characteristics | n | % | Poor/Fair/Good | Very Good | Excellent |

| Age (in mos) | |||||

| 1–5 | 323 | 27.9 | |||

| 6–23 | 423 | 36.6 | 37 (10.5) | 82 (23.2) | 234 (66.3) |

| 24–59 | 410 | 35.5 | 86 (21.0) | 111 (27.1) | 213 (51.9) |

| Missing | 2 | ||||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 588 | 50.8 | 63 (15.5) | 103 (25.3) | 241 (59.2) |

| Male | 570 | 49.2 | 61 (16.5) | 93 (25.2) | 215 (58.3) |

| Dentate | |||||

| Yes | 779 | 67.3 | 124 (16.0) | 196 (25.3) | 456 (58.8) |

| No | 379 | 32.7 | |||

| Birth order | |||||

| Only child | 270 | 28.4 | 15 (10.1) | 32 (21.6) | 101 (68.2) |

| First born | 160 | 16.8 | 39 (24.8) | 44 (28.0) | 74 (47.1) |

| Middle | 108 | 11.4 | 23 (21.7) | 29 (27.4) | 54 (50.9) |

| Last | 413 | 43.4 | 30 (12.6) | 57 (23.9) | 151 (63.5) |

| Missing | 207 | ||||

COHL = Carolina Oral Health Literacy.

n = number of subjects in stratum.

Literacy was distributed normally [X2 = 2.0, degrees of freedom (df) = 2, p > 0.05], with mean of 15.8 (SD = 5.3). Caregivers’ knowledge scores were distributed non-normally (X2 = 72.1, df = 2, p < 0.05), with mean of 4.8 (SD = 1.0), with over two-thirds scoring 5 or above. Higher education and age were associated with higher knowledge scores. More pronounced gradients were observed in literacy scores for education, race, and age. We found a significant positive correlation between literacy and knowledge: Spearman’s ρ = 0.19; 95% CI = 0.13, 0.24.

The vast majority reported daily brushing/cleaning children’s teeth/gums; however, 37% of dentate children were reported as having been put to bed with a bottle. We found lower literacy scores among caregivers reporting no daily brushing/cleaning (mean REALD-30 difference = -1.17; 95% CI = -2.33, -0.01; reference, daily brushing/cleaning) and those who had put their child/infant to bed with a bottle (mean REALD-30 difference = -1.28; 95% CI = -1.94, -0.62; reference, having never put their child/infant to bed with a bottle). Daily brushing/cleaning was associated with better reported oral health status (OR = 0.70; 95% CI = 0.46, 1.06) and nighttime bottle use with worse (OR = 1.72; 95% CI = 1.29, 2.28).

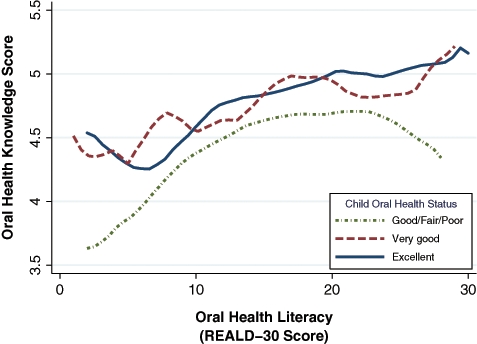

The association between knowledge and literacy scores for strata of status is displayed in the Fig. The illustration suggests that low literacy and knowledge co-exist, particularly among those with worse status. Higher literacy was associated with a trend for better reported status.

Figure.

Relationship between oral health literacy and oral health knowledge for strata of infant oral health status among the Carolina Oral Health Literacy study participants, illustrated by local polynomial fit functions.

The association of literacy and race with knowledge and status is presented in Table 3. For both models, estimates above 1.0 indicate worse reported oral health and poorer oral health knowledge. Independent of race, age, education, and number of children, caregivers’ low literacy was associated with increased odds of reporting poorer status (OR = 1.44; 95% CI = 1.02, 2.05) and lower knowledge scores (OR = 1.86; 95% CI = 1.41, 2.45). American Indian caregivers were the most likely to report poorer status (OR = 1.56; 95% CI = 1.06, 2.29; reference, Whites).

Table 3.

Multivariate Ordinal Logistic Regression Results* of Oral Health Literacy and Race on Reported Oral Health Status and Oral Health Knowledge among the COHL Study Caregivers (n = 1158)

| Child Oral Health Status† |

Oral Health Knowledge‡ |

|

|---|---|---|

| Regressor | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Race | ||

| White | referent | referent |

| African American | 1.04 (0.75, 1.44) | 1.16 (0.91, 1.48) |

| American Indian | 1.56 (1.06, 2.29) | 1.06 (0.78, 1.44) |

| Oral Health Literacy | ||

| OHL score ≥ 13 | referent | referent |

| OHL score < 13 | 1.44 (1.02, 2.05) | 1.86 (1.41, 2.45) |

Models included disjoint indicator terms for caregivers’ age, number of children, and education level. †Status was coded as a 3-level categorical variable where 1 = excellent, 2 = very good, and 3 = poor/fair/good. ‡Knowledge was coded as an ordinal variable corresponding to the knowledge quiz score (range: 0–6). Odds ratios above 1 indicate poorer reported oral health status and lower oral health knowledge scores.

COHL = Carolina Oral Health Literacy.

OR = odds ratio.

CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

There is strong evidence linking caregivers’ low health literacy with negative early childhood health-related behaviors, independent of socio-economic risk indicators (Sanders et al., 2009a; Yin et al., 2009). Deleterious health behaviors (Yin et al., 2007; DeWalt and Hink, 2009) and decreased use of preventive services (Sanders et al., 2007) are 2 potential mediating factors between low literacy and poor pediatric health outcomes. We have examined the interrelationship among literacy, health-related knowledge, and reported behavior in the oral health context.

One of our major thrusts was to examine patterns of association between oral health literacy and oral-health-related factors. We recognize that our findings may be influenced by both social desirability as well as the expert counseling given by the WIC counselors. Even so, over 88% of the caregivers reported daily toothbrushing or cleaning for dentate children, an impressively high figure. The lack of daily toothbrushing and the use of the nighttime bottle were associated with lower literacy. The findings on feeding behaviors suggest that there are opportunities for caregiver education relative to nighttime bottle use; at the same time, it is clear that oral health messages may have reached and resonated with many of these caregivers, especially as related to the consumption of juice and snacks. We attribute this positive finding to the fact that the WIC counselors in North Carolina are nutritionists by training, and they emphasize the judicious use of juice and snacks.

We acknowledge as a potential study limitation the reliance on a generic parental report for a child’s oral health status. Another potential threat to validity is the possibility that caregivers who do not value oral health may report less accurate oral health information. However, analysis of published data supports the strength and validity of such subjective reports. Talekar et al. (2005) analyzed NHANES III data and reported a concordance of parental-reported early childhood oral health status with actual disease and perceived needs.

As is the case with all investigations examining health literacy, it must be acknowledged that low literacy may be a threat to the study’s validity because of the participants’ difficulty in reading and comprehending survey questions (Al-Tayyib et al., 2002). This threat was mitigated in the present study by reliance on in-person interviews by trained personnel.

Although we relied on a convenience sample, the WIC population offered a superb model to address our research aims. Participants were derived from a low-income population, a homogeneity beneficial for investigating the independent impacts of oral health literacy. While limited to one state, the participants were recruited from 9 different sites, representing a broad diversity of individuals, including a robust sample of American Indians.

All previous oral health literacy research has examined care-seeking individuals (Jones et al., 2007; Lee at al., 2007; Miller et al., 2010). A special strength of this study is that the participants were not recruited from a clinical environment, a setting that can introduce selection bias. Considering the strong correlation among knowledge, behaviors, and caries development (Watson et al., 1999; Patrick et al., 2006), our finding of correlation among literacy, knowledge, and behaviors is important. In this context, it should be underscored that oral health literacy estimates derived from word recognition tests such as REALD-30 have been previously shown to correlate well with comprehension and functional health literacy (Gong et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2007).

We found higher literacy to be associated with better reported oral health status, independent of knowledge and other covariates, including race, education, age, and number of children. These findings suggest that oral health literacy is a fundamental dimension that confers oral health impacts above and beyond education and socio-demographic characteristics. This is a seminal discovery, because it may open the door for a possible intervention. It is impossible to change age or race, and very challenging to change education; however, it may be possible, with the right intervention, to enhance oral health literacy in a population of caregivers such as the one under study here, a strategy that has been successful in the medical setting (Bennett et al., 2003; Chew et al., 2004; Sanders et al., 2009b). Another conceptually different strategy to improve caregivers’ behaviors may be to develop an approach that aims educational messages at the literacy level of the recipients.

Under the conditions of this study involving low-income WIC caregivers and young children, lower literacy was consistently and independently associated with lower knowledge and worse caregiver-reported oral health status. Lower literacy was also associated with deleterious oral health behaviors. These findings suggest that REALD-30 can be used to strategically identify caretakers with lower early childhood oral health knowledge and young children with worse oral health status. Taken together, the findings set the stage for the development of strategies that have potential to enhance caregivers’ behaviors to have a favorable impact on the oral health of those children who are among the most vulnerable to ECC.

Acknowledgments

The COHL Project is supported by a grant from the NIDCR (Grant#R01DE018045). A preliminary report of this paper was presented at the 39th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Dental Research, Washington, DC, March 3-6, 2010.

References

- Al-Tayyib AA, Rogers SM, Gribble JN, Villarroel M, Turner CF. (2002). Effect of low medical literacy on health survey measurements. Am J Public Health 92:1478-1480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstutz RD, Rozier RG. (1995). Community risk indicators for dental caries in school children: an ecologic study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 23:129-137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrus MR, Roth MT. (2002). Health literacy: a review. Pharmacotherapy 22:282-302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett IM, Robbins S, Al-Shamali N, Haecker T. (2003). Screening for low literacy among adult caregivers of pediatric patients. Fam Med 35:585-590 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. (2004). Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med 36:588-594 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino RB, Belanger A, D’Agostino RB., Jr (1990). A suggestion for using powerful and informative tests of normality. Am Statistician 44:316-321 [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt DA, Hink A. (2009). Health literacy and child health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Pediatrics 124(Suppl 3):265-274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. (2004). Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med 19:1228-1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass JM, Tinanoff N, Tang JM, Altman DS. (2001). Dental caries patterns and oral health behaviors in Arizona infants and toddlers. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 29:14-22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein BL, Chinn CH. (2009). Update on disparities in oral health and access to dental care for America’s children. Acad Pediatr 9:415-419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong DA, Lee JY, Rozier RG, Pahel BT, Richman JA, Vann WF., Jr (2007). Development and testing of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Dentistry (TOFHLiD). J Public Health Dent 67:105-112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R, Nicoll AD, Adair PM, Pine CM. (2004). Risk factors for dental caries in young children: a systematic review of the literature. Community Dent Health 21(1 Suppl):71S-85S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M, Lee JY, Rozier RG. (2007). Oral health literacy among adult patients seeking dental care. J Am Dent Assoc 138:1199-1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Rozier RG, Lee SY, Bender D, Ruiz RE. (2007). Development of a word recognition instrument to test health literacy in dentistry: the REALD-30—a brief communication. J Public Health Dent 67:94-98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Divaris K, Rozier RG, Baker D, Vann WF., Jr (2010). Oral health literacy levels among a low income population (abstract). J Dent Res 89(Spec Iss A):1206 [Google Scholar]

- Mathu-Muju KR, Lee JY, Zeldin LP, Rozier RG. (2008). Opinions of Early Head Start staff about the provision of preventive dental services by primary medical care providers. J Public Health Dent 68:154-162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E, Lee JY, DeWalt DA, Vann WF., Jr (2010). Impact of caregiver literacy on children’s oral health outcomes. Pediatrics [Epub ahead of print, June 14, 2010] (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, Committee on Health Literacy (2004). Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick DL, Lee RS, Nucci M, Grembowski D, Jolles CZ, Milgrom P. (2006). Reducing oral health disparities: a focus on social and cultural determinants. BMC Oral Health 6(Suppl 1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LM, Thompson VT, Wilkinson JD. (2007). Caregiver health literacy and the use of child health services. Pediatrics 119:e86-e92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LM, Federico S, Klass P, Abrams MA, Dreyer B. (2009a). Literacy and child health: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 163:131-140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LM, Shaw JS, Guez G, Baur C, Rudd R. (2009b). Health literacy and child health promotion: implications for research, clinical care, and public policy. Pediatrics 124(Suppl 3):306-314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shick EA, Lee JY, Rozier RG. (2005). Determinants of dental referral practices among WIC nutritionists in North Carolina. J Public Health Dent 65:196-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talekar BS, Rozier RG, Slade GD, Ennett ST. (2005). Parental perceptions of their preschool-aged children’s oral health. J Am Dent Assoc 136:364-372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinanoff N, Kanellis MJ, Vargas CM. (2002). Current understanding of the epidemiology mechanisms, and prevention of dental caries in preschool children. Pediatr Dent 24:543-551 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomar SL, Reeves AF. (2009). Changes in the oral health of US children and adolescents and dental public health infrastructure since the release of the Healthy People 2010 Objectives. Acad Pediatr 9:388-395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services (2000). Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, US Dept. of Health and Human Services; 7:158-168 Available at: http://www2.nidcr.nih.gov/sgr/sgrohweb/home.htm (URL accessed June 30, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- Watson MR, Horowitz AM, Garcia I, Canto MT. (1999). Caries conditions among 2–5-year-old immigrant Latino children related to parents’ oral health knowledge, opinions and practices. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 27:8-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HS, Dreyer BP, Foltin G, van Schaick L, Mendelsohn AL. (2007). Association of low caregiver health literacy with reported use of nonstandardized dosing instruments and lack of knowledge of weight-based dosing. Ambul Pediatr 7:292-298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HS, Johnson M, Mendelsohn AL, Abrams MA, Sanders LM, Dreyer BP. (2009). The health literacy of parents in the United States: a nationally representative study. Pediatrics 124(Suppl 3):289-298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]