Abstract

Focally extensive alopecia affecting the distal limbs is a common clinical finding in rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) colonies and is both a regulatory and colony-health concern. We performed diagnostic examinations including physical exams, bloodwork, skin scrapes, surface cytology, and surface bacterial–fungal cultures on 17 rhesus macaques with this presentation of alopecia. Skin biopsies from alopecic skin obtained from each macaque were compared with those of normal skin from the same animal. Immunohistochemistry and metachromatic staining for inflammatory cells were performed to compare alopecic and normal skin. In addition, we compared these biopsies with those previously obtained from macaques with generalized alopecia and dermal inflammatory infiltrates consistent with cutaneous hypersensitivity disorders and with those from animals with normal haircoats. Bacterial and fungal cultures, skin scrapes, surface cytology, and bloodwork were unremarkable. Affected skin showed only mild histologic alteration, with rare evidence of trichomalacia and follicular loss. Numbers of mast cells and CD3+ lymphocytes did not differ between alopecic and normally haired skin from the same animal. The number of mast cells in alopecic skin from animals in the current cohort was significantly lower than that in skin of animals previously diagnosed with a cutaneous hypersensitivity disorder. Numbers of both mast cells and CD3+ lymphocytes in alopecic skin from the current cohort were similar to those from biopsies of animals with normal haircoats. Together, the clinical findings and pathology are consistent with a psychogenic origin for this pattern of alopecia in rhesus macaques.

Alopecia is a major concern in rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) colonies from both a regulatory and colony-health perspective and is currently a focus of research.3,4,6,10,12,18,26,31,32 Numerous causes have been reported, including inflammatory,2,19,25,27 allergic,18,21 genetic,1 nutritional,8,24,28,33 infectious,15 and idiopathic13 etiologies. Despite this information, a default diagnosis of psychogenic self-inflicted alopecia often is reached in the absence of an evidence-based diagnostic approach. Experience in comparative veterinary and human dermatology indicates that there is no single cause of alopecia. Because alopecia can be either a primary or secondary lesion in dermatology, veterinarians and regulatory authorities should have a full understanding of the breadth of diseases that can lead to alopecia and to pursue a systematic dermatologic diagnostic plan to direct appropriate treatment.

Focally extensive alopecia affecting the distal limbs (Figure 1) is a common clinical pattern in the colony we describe here. Generally, these macaques have irregularly shaped patches of hair loss on their forearms or lower legs (or both) that is not necessarily associated with diffuse alopecia on other anatomic sites. This clinical pattern is quite distinct from the generalized alopecia seen in other macaques.

Figure 1.

Clinical appearance of distal limb alopecia, with a well circumscribed area of hair loss without underlying skin inflammation.

Herein, we describe the clinical and pathologic evaluations of rhesus macaques with this specific pattern of alopecia. Locally extensive, noninflammatory alopecia is the only presenting clinical sign in these animals. On the basis of exclusion of other differential diagnoses, we conclude that psychogenic alopecia is the presumptive cause.

Materials and Methods

Rhesus macaques were housed at the New England Primate Research Center (Southborough, MA) and maintained in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.14 The facility is AAALAC-accredited, and all work was approved by Harvard Medical School's Standing Committee on Animals.

The Center maintains a large breeding colony of Indian-origin rhesus macaques in addition to a cohort of macaques that are active in a variety of research protocols. Virologic testing is performed quarterly to semiannually for SIV, simian T-lymphotropic virus type 1, B virus, and simian retrovirus type D as previously described,9 and the breeding colony has been specific pathogen-free from these agents, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and measles virus since 1988. All animals in the colony are monitored monthly for alopecia, as previously described,18 on a scale of 0 to 5 (0, no observable alopecia; 1, alopecia involving less than 10% of the integument; 2, alopecia of 10% to 20% of the integument; 3, 20% to 40% of the integument affected; grade 4, 40% and 60% of the integument affected; and 5, alopecia of more than 60% of the integument).

We selected 17 macaques with grade 1 or 2 alopecia and prominent localization to the forearms (Figure 1) or lower legs for further diagnostic work-up. These macaques were all singly housed, either temporarily or permanently, in stainless steel cages conforming to the requirements set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.14 Animals were selected to exclude those with experimental histories that would interfere with this investigation or for whom the procedures in this study would interfere with ongoing experiments. In addition, macaques that had recently given birth were disqualified, to exclude cases of postpartum alopecia. Over the course of 2 to 3 mo, each animal was sedated with ketamine (10 to 15 mg/kg IM; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA) for a diagnostic examination.

Physical examination was performed on all macaques to assess the overall health of the animal and extent of alopecia. Alopecia was assessed by using a standardized dermatology examination form to document lesion type, distribution, and both the type of additional diagnostics and location at which these were performed. In a subset of animals (12 of 17), approximately 6 mL blood was drawn from the femoral vein for a CBC, serum chemistry profile, or both. CBC were performed on a multispecies hematology instrument (Hemavet HV1700FS, Drew Scientific, Waterbury, CT), and chemistry profiles were sent to a diagnostic lab (Idexx Laboratories, North Grafton, MA) for testing.

Additional diagnostics performed during the time of physical examination included skin scrapes (13 of 17 macaques), surface cytology preparations (13 of 17), surface bacterial culture (10 of 17), and dermatophyte cultures (10 of 17). Not all diagnostics were performed on all animals due to various research constraints unrelated to the present project. Skin scrapes were performed by using a blunted scalpel blade, which was scraped against the surface of the skin to remove surface crust material, epidermal cells, and contents of hair follicles. The material was placed onto a glass slide with mineral oil and evaluated microscopically for evidence of parasitism or other pathology. Surface preparations were performed by using double-sided tape adhered to a glass slide. The sticky surface of the slide was pressed to affected regions of skin and stained with a modified Wright–Giemsa stain. Slides were evaluated microscopically for evidence of fungal and bacterial infection. Bacterial cultures were obtained by rubbing a sterile culturette (BBL CultureSwab Liquid Amies, Beckton, Dickinson, and Company, Sparks, MD) over affected skin. Swabs were cultured on tryptose blood agar, Columbia blood agar, and CM agar. Several hairs were plucked from areas immediately adjacent to alopecic areas and placed in sterile media for fungal culture in Sabourand dextrose agar and dermatophyte test medium. Bacterial and fungal cultures were performed at Charles River Research Animal Diagnostic Services (Wilmington, MA).

During the same anesthetic episode, skin biopsies were obtained from all 17 macaques. Each animal was biopsied in both affected skin and unaffected skin of the same extremity. Generally, these biopsies were obtained from skin over the humerus on the lateral aspect of the arm or over the femur on the lateral aspect of the leg. This protocol allowed each animal to serve as its own control when evaluating biopsies both histologically and with special stains. The areas to be biopsied were neither shaved nor prepped aseptically so as to preserve surface material for histologic analysis. Each biopsy site was marked, and lidocaine was instilled subcutaneously. A 6-mm punch biopsy instrument was used to obtain biopsies from both affected and unaffected areas. The biopsy site was sutured, and samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for evaluation by light microscopy. Hair cycle stage was compared between unaffected and alopecic skin on the same animal.

Immunohistochemistry for T cells (CD3+) was performed by using an immunostaining technique on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues, as previously described.34 Briefly, 5-µm sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded alcohol, and rinsed in Tris-buffered saline. Sections were incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min to block endogenous peroxidases and rinsed in Tris-buffered saline for 5 min. Epitope retrieval was accomplished by using heat pretreatment (20 min in microwave). Nonspecific antigen binding was blocked by incubating slides for 10 min with a commercially available protein blocking solution (Dako Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA). Positive control tissue and irrelevant antibody controls were used in each run. Slides were incubated with primary (CD3, catalog no. A0452, Dako) and secondary (biotinylated goat antirabbit CD3) antibodies for 30 min. Color was developed by using freshly prepared ABC Elite solution (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) followed by washing in Tris-buffered saline. Diamino-benzidine-tetrahydrochloride-dihydrate was applied as a chromogen. Sections were counterstained with Mayer hematoxylin, dehydrated through graded ethanol, cleared in xylene, and cover-slipped.

To specifically highlight mast cells, toluidine blue staining was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Sections (5-µm) were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded alcohol, and rinsed in water. Sections were stained with filtered toluidine blue for 15 min and washed in tap water, dehydrated through graded ethanol, cleared in xylene, and cover-slipped.

To evaluate the degree of dermal and perifollicular fibrosis, trichrome stain was applied to formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues according to standard protocols.

Cellular infiltrates were quantified by a single investigator (JAK), who was blinded to alopecia status at the time of counting. Labeled cells were counted in five 20× fields, and these counts averaged for both affected and unaffected areas of skin for each animal. The resulting count was expressed as number of cells per millimeter of epidermis. Cell counts were performed in the same manner as for a previous report; 18 therefore, cell counts for both normal and alopecic skin from the current cohort were compared with those previously reported. Statistical analysis was performed by using GraphPad Prism (version 5.01, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Student t tests were used to compare animals between groups and affected and unaffected skin from a single animal.

Results

Demographic information.

The overall demographics of rhesus macaques with alopecia in this colony have been previously reported and increasing age, female gender, and source colony were identified as contributors to the development of alopecia. Overall, 48% of singly housed or pair-housed rhesus macaques had alopecia at some point in their clinical history. 18 Macaques with mild alopecia localized mainly to the distal limbs are the most common single presentation amongst those animals with alopecia, accounting for 45% of documented cases of alopecia in singly housed macaques. Animals with this presentation had an average age of 8.3 y, which was not significantly different when compared with the overall colony age of 7.4 y (t test; P = 0.1436) but was significantly higher than the average age of colony animals without a history of alopecia (6.2 y, t test; P = 0.0009). Macaques as young as 3 y old had this presentation. Both male and female macaques were affected in approximately equal numbers (male, 53%; female, 47%), a distribution that is nearly identical to the overall colony distribution of singly housed macaques (male, 54%; female, 46%). Whereas most of the macaques with distal limb alopecia were born and raised at our facility, animals from a variety of colonies had this presentation, including macaques raised indoors and outdoors.

Results of comprehensive dermatologic examination.

We selected 17 rhesus macaques (representing approximately 25% of colony animals with this presentation) with grade 1 or 2 alopecia of the forearms or lower legs for evaluation. Physical examinations were unremarkable except for focally extensive alopecia of well-demarcated but ill-defined areas of skin on the forearms, lower legs, or both. In most macaques, the alopecic areas were completely denuded of hair. However, others showed thinning of the hair with multiple smaller areas of more complete alopecia. Skin underlying the alopecic areas had no evidence of excoriation, erythema, or other lesions, except for mild lichenification in some cases. Normal haircoats covered other parts of the body, and these animals did not have evidence of truncal alopecia.

Bloodwork results were unremarkable for all 12 macaques tested. There was no evidence of renal disease, liver disease, endocrine disease, or systemic inflammatory disease.

The only bacterium isolated on surface skin culture was Staphylococcus aureus, which was isolated from all 10 macaques sampled. Growth ranged from minimal to moderate between animals. None of the macaques showed evidence of bacterial dermatitis on skin biopsy. S. aureus can be considered a normal commensal in man17 and presumably in rhesus macaques as well. All fungal cultures and skin scrapings were negative, suggesting that neither fungal disease nor parasitic disease played a significant role in the alopecia demonstrated by these animals.

Surface preparations of affected skin confirmed the results of bacterial culture and fungal culture. Most animals showed variable numbers of bacterial cocci which, in light of culture results, are suspected to be S. aureus organisms. Several macaques also were positive for Malassezia spp. yeast identified by their characteristic peanut-like shape. Because Malassezia spp. organisms are not uncommon in normal necropsy specimens at the colony facility, they are not suspected of contributing to disease. In addition, like S. aureus, Malassezia spp. are part of the normal skin microflora in both humans and veterinary species.7,16

Skin biopsies.

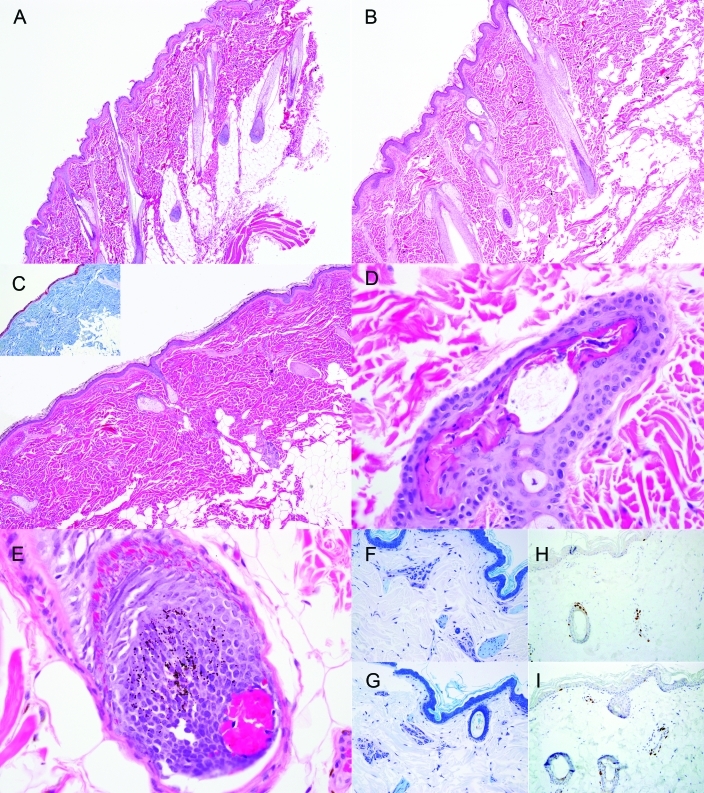

Skin biopsies from unaffected (Figure 2 A) and alopecic (Figure 2 B) skin from the same animal were frequently indistinguishable. In general, no difference was noted in the number of anagen, catagen, and telogen follicles between unaffected and alopecic biopsies from the same animal, and the majority of hairs were in anagen. Two of the macaques had reduced numbers of anagen follicles with corresponding increases in catagen follicles, and another 2 animals had increased numbers of telogen follicles. Rarely, biopsies showed reduced numbers of hair follicles in affected dermis (n = 1, Figure 2 C), trichomalacia (n = 3, Figure 2 D), or intrafollicular hemorrhage (n = 2, Figure 2 E). However, these findings were infrequent. There was negligible perivascular inflammation, no bulbar inflammation or folliculitis, and no evidence of acanthosis, spongiosis, edema, dermal fibrosis, or other pathology that might be expected in animals with more generalized alopecia.18,31,32

Figure 2.

(A) Unaffected skin had a thin epidermis, parallel hair follicles, and little inflammation. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; magnification, ×4. (B) Affected forearm skin generally looked very similar, with no notable differences or obvious epidermal or hair follicle pathology. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; magnification, ×4. (C) Rarely, there was generalized loss of follicular structures but still no inflammation or other pathology. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; magnification, ×4. Trichrome staining (inset) showed no fibrosis or other changes. Several sections had (D) damaged hair follicles or (E) intrafollicular hemorrhage, consistent with trichotillomania. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; magnification, ×40. There were no notable differences in mast cells (stained purple with toluidine blue; magnification, ×20) between (F) unaffected and (G) affected skin or in the numbers of CD3+ T cells (stained brown with CD3 immunostain with DAB chromogen; magnification, ×20) between (H) unaffected and (I) affected skin.

Dermal inflammation.

To quantify perivascular inflammation, toluidine blue staining for mast cells and immunohistochemistry for CD3+ lymphocytes were performed. In this cohort, numbers of neither mast cells (mean: alopecic, 9.69; unaffected, 10.28; t test, P = 0.5984) nor CD3+ lymphocytes (mean: alopecic, 17.56; unaffected 21.45; t test, P = 0.0625) were elevated in alopecic skin (Figure 2 G and I, respectively) compared with normal skin (Figure 2 F and H, respectively) from the same animal.

Numbers of CD3+ lymphocytes and mast cells in the current macaques were compared with cell counts obtained during a previous study,18 in which we demonstrated that cell counts were elevated in animals with alopecia compared with those without alopecia and increased with increasing alopecia score. The only difference noted when comparing the biopsies from alopecic skin in the current group with both normal and affected skin in the previous report was a significantly (t test, P = 0.0030) reduced number of mast cells in the alopecic skin of the current macaques (mean, 9.69) compared with alopecic skin from the previous report (mean, 14.79). The number of mast cells in the alopecic skin biopsies of the current group were similar to those found in normal skin in the previous report (mean, 9.93; t test, P = 0.8942). The numbers of CD3+ lymphocytes in alopecic skin did not differ between the current cohort (mean, 17.56) and either unaffected macaques (mean, 13.41; t test, P = 0.0938) or the alopecic animals (mean, 25.36; t test, P = 0.0963) from the previous report.

We also compared the numbers of inflammatory cells in the biopsies from unaffected skin of the current group with those from both alopecic and unaffected skin from the previous cohort.18 As expected, the numbers of mast cells were significantly (t test, P = 0.0095) reduced in unaffected skin from the current macaques (mean, 10.28) compared with alopecic skin from the previous report (mean, 14.79). Numbers of mast cells did not differ between normal skin of both groups (mean: current, 10.28; previous, 9.93; t test, P = 0.8472). However, numbers of CD3+ lymphocytes in the unaffected skin of the current group (mean, 21.45) were elevated compared with normal skin (mean, 13.41; t test, P = 0.0249) but did not differ from those of alopecic skin (mean, 25.36; t test, P = 0.4241) in the previous report.

Discussion

In the present study, we followed a systematic dermatologic diagnostic plan to investigate a specific pattern of localized lower limb alopecia in a group of rhesus macaques. Alopecia was not associated with bacterial, fungal, or parasitic agents. A comparison of skin biopsies between affected and unaffected skin from the affected macaques demonstrated noninflammatory dermatosis with mild hair follicle pathology and some evidence of hair follicle damage, consistent with presumptive psychogenic alopecia.

We previously have demonstrated that some alopecic rhesus macaques, particularly those with more generalized alopecia or alopecia associated with clinical signs such as erythema and pruritus, have skin pathology consistent with a cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction.18 Skin biopsies in these animals were characterized by prominent perivascular mononuclear inflammation composed of increased numbers of mast cells, lymphocytes, and histiocytes, together with mild to moderate acanthosis and hyperkeratosis. In these cases, the inflammation caused pruritus, resulting in self-inflicted alopecia.

We compared biopsies from the current cohort of macaques with those from alopecic and normal skin from the previous survey. Alopecic macaques in the current study had significantly fewer dermal mast cells than did alopecic animals in the previous study. Numbers of CD3+ lymphocytes in alopecic skin did not differ significantly between the 2 cohorts. Together, these findings indicate that the animals in the current group had less inflammation than did those surveyed previously. This result is consistent with a presumptive psychogenic origin for the current pattern of alopecia.

Dermatology of nonhuman primates requires a comparative perspective. In the current study, comparison to feline psychogenic self-inflicted alopecia and human trichotillomania is warranted. Feline psychogenic alopecia is a relatively uncommon diagnosis made by exclusion of pruritic causes of self-traumatic alopecia, namely infectious, parasitic, and allergic disease.11,22 Psychogenic alopecia is characterized by self-trauma, resulting in removal of hairs in well-demarcated, often symmetric, regions, frequently without associated lesions in the exposed skin. Trichomalacia, characterized by distorted hair shafts within amorphous tricholemmal keratin, may be found. Occasionally there are increases in inflammatory infiltrates in the superficial dermis as well as rare mural folliculitis. However, hair follicle abnormalities and inflammation usually are not noted in cases of feline psychogenic self-inflicted alopecia, and skin biopsies can be essentially normal.11,22

In humans, trichotillomania is a clinical disease classified as an impulse control disorder similar to obsessive–compulsive disorder, characterized by repetitive pulling and twisting of hair, resulting in clinically nonscarring alopecia.29 Histopathologic examination of tissues from human patients with trichotillomania demonstrate trichomalacia, follicular and perifollicular hemorrhage, abnormally shaped hair follicles, and lack of inflammation.30 One review of 66 patients with trichotillomania reported the most consistent findings as: catagen hairs (74%), pigment casts (61%), microscopic alopecia (50%), and traumatized hair bulbs (21%). Bulbar inflammation and atrophic anagen hairs were absent.23 Similar results were seen in a second survey of 26 patients.5

Several of these changes, including trichomalacia, follicular hemorrhage, and abnormally shaped follicles, were identified in the animals in this report. In addition, catagen hairs were readily identified in 2 of 17 (12%) macaques, a lower frequency than in humans. In our animals, we observed only sporadic trichomalacia, and pigmented casts were not seen.

It is important to note that, in humans, histopathologic diagnosis using these characteristic features is most effective in tissue specimens from areas affected less than 8 wk.23 This indicates that the timing and site selection of biopsies may affect the histopathologic diagnosis. This issue may explain the histopathologic differences between self-inflicted alopecia in humans, felines, and macaques and requires further investigation.

Anecdotally, caretakers for the current rhesus macaques noted them picking at their hair, especially that of their forearms, with some frequency. A systematic behavioral analysis of the animals in this group was not performed, but the pattern (Figure 1) of well-defined but irregular areas of alopecia is similar to that observed in trichotillomania. However, most of the biopsies obtained from this cohort showed no distinct differences from that of normal skin, and few had evidence of trichomalacia or other findings typical in human trichotillomania. The absence of histopathologic findings in the current study is more typical of the pattern seen with feline psychogenic alopecia.

We do not propose that the clinical pattern in the current macaques is completely analogous to feline psychogenic alopecia. However, the absence of histopathologic findings and the clinical presentation in these rhesus macaques in many ways parallels that of psychogenic alopecia in cats. In both conditions, there are focally extensive regions of near complete alopecia with minimal pathology of underlying skin. In addition, lesions are most prevalent on easily accessed areas of the body—predominantly the medial forelimbs in rhesus macaques and medial forelimbs, caudal abdomen, and inner thigh in cats.22 We propose that in macaques, as in cats, psychogenic alopecia can be diagnosed through exclusion of other differential diagnoses causing pruritus. Whereas seeing animals pulling hair from affected regions would be helpful in confirming the diagnosis, obtaining this proof is difficult from a technical perspective because rhesus macaques often hide various behaviors when under direct observation. Video monitoring of macaques to capture hair-pulling behavior would have been beneficial but was beyond the scope of this report.

Clinicians faced with cases of alopecia need to recognize specific patterns and have a standard diagnostic plan. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of information in the nonhuman primate dermatologic literature regarding these patterns and their associated diagnoses. By recognizing the pattern presented in this report in conjunction with exclusion of other differential diagnoses, clinicians can be justified in attempting behavioral therapy, such as enrichment with forage boards, positive reinforcement training, and socialization, to ameliorate the clinical signs. However, it is important to recognize that this alopecia is relatively mild when compared with the more extensive alopecia that also is common in rhesus macaques. Furthermore, retrospective analyses of animals with more serious psychologic behaviors, such as self-biting, have not correlated those behaviors with alopecia,20 and there is no evidence that animals presenting with alopecia will go on to develop self-injurious behavior or other more serious conditions.

Alopecia is not only a concern from an animal welfare perspective but also as a potential confounder of experimental research. Dermal inflammation associated with certain causes of alopecia may affect animals’ responses to vaccines, viral inoculations, intradermal tuberculin tests, and so forth. The rhesus macaques in the current report had reduced inflammation, compared with monkeys with more generalized alopecia. This difference indicates that focally extensive distal limb alopecia is less concerning as a potential confounder of experimental research than are other presentations of alopecia.

Focally extensive distal limb alopecia was the only clinical sign seen in some cynomolgus macaques at our facility. A previous study reports that cynomolgus macaques are less likely to develop cutaneous inflammation when compared with SPF rhesus macaques.18 This difference suggests that a different etiology may be responsible for distal limb alopecia and further supports the notion that this presentation may not interfere with experimental work.

The results of the current study indicate that the pathology and clinical findings of rhesus macaques with focally extensive alopecia of their distal limbs is consistent with psychogenic alopecia. This report adds to the growing literature on alopecia in nonhuman primate colonies and provides a standard diagnostic plan for clinicians to use in evaluation of nonhuman primates with alopecia. Future work should be aimed at performing behavioral analysis in animals with this presentation to determine whether they have other behavioral abnormalities and to make direct confirmation of hair-pulling behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by NIH/NCRR grant P51 RR000168-47. We thank the staff of the histology lab at the New England Primate Research Center for their hard work associated with this project. Kristen Toohey assisted with photo preparation. Various veterinary technicians and students in the Department of Primate Resources assisted during biopsy and other diagnostic procedures.

References

- 1.Ahmad W, Ratterree MS, Panteleyev AA, Aita VM, Sundberg JP, Christiano AM. 2002. Atrichia with papular lesions resulting from mutations in the rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) hairless gene. Lab Anim 36:61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beardi B, Wanert F, Zoller M, Freyschmidt-Paul P, Bodemer W, Kaup FJ. 2007. Alopecia areata in a rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). J Med Primatol 36:124–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beisner BA, Isbell LA. 2008. Ground substrate affects activity budgets and hair loss in outdoor captive groups of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Am J Primatol 70:1160–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beisner BA, Isbell LA. 2009. Factors influencing hair loss among female captive rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Appl Anim Behav Sci 119:91–100 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergfeld W, Mulinari-Brenner F, McCarron K, Embi C. 2002. The combined utilization of clinical and histological findings in the diagnosis of trichotillomania. J Cutan Pathol 29:207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernstein JA, Didier PJ. 2009. Nonhuman primate dermatology: a literature review. Vet Dermatol 20:145–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cafarchia C, Otranto D. 2008. The pathogenesis of Malassezia yeasts. Parassitologia 50:65–67 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coward DG, Whitehead RG. 1972. Experimental protein-energy malnutrition in baby baboons. Attempts to reproduce the pathological features of kwashiorkor as seen in Uganda. Br J Nutr 28:223–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniel MD, Letvin NL, Sehgal PK, Schmidt DK, Silva DP, Solomon KR, Hodi FS, Jr, Ringler DJ, Hunt RD, King NW, Desrosiers RCl. 1988. Prevalence of antibodies to 3 retroviruses in a captive colony of macaque monkeys. Int J Cancer 41:601–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeJoseph M, Taylor RS, Baker M, Aregullin M. 2002. Fur-rubbing behavior of capuchin monkeys. J Am Acad Dermatol 46:924–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross TL, Gross TL. 2005. Skin diseases of the dog and cat: clinical and histopathologic diagnosis, 2nd ed, Ames (IA): Blackwell Science [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honess P, Gimpel J, Wolfensohn S, Mason G. 2005. Alopecia scoring: the quantitative assessment of hair loss in captive macaques. Altern Lab Anim 33:193–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horenstein VD, Williams LE, Brady AR, Abee CR, Horenstein MG. 2005. Age-related diffuse chronic telogen-effluvium–type alopecia in female squirrel monkeys (Saimiri boliviensis boliviensis). Comp Med 55:169–174 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karjala Z, Desch CE, Starost MF. 2005. First description of a new species of Demodex (Acari: Demodecidae) from rhesus monkey. J Med Entomol 42:948–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klotz SA. 1989. Malassezia furfur. Infect Dis Clin North Am 3:53–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kooistra-Smid M, Nieuwenhuis M, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. 2009. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus burn wound colonization. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 57:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer J, Fahey M, Santos R, Carville A, Wachtman L, Mansfield K. 2010. Alopecia in rhesus macaques correlates with immunophenotypic alterations in dermal inflammatory infiltrates consistent with hypersensitivity etiology. J Med Primatol 39:112–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowe NJ, Chalet M, Breeding J, Kean C, Russell DH. 1982. Psoriasiform dermatosis in a rhesus monkey. Epidermal labeling indexes, polyamines, and histopathologic findings. Arch Dermatol 118:993–996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lutz C, Well A, Novak M. 2003. Stereotypic and self-injurious behavior in rhesus macaques: a survey and retrospective analysis of environment and early experience. Am J Primatol 60:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macy JD, Jr, Huether MJ, Beattie TA, Findlay HA, Zeiss C. 2001. Latex sensitivity in a macaque (Macaca mulatta). Comp Med 51:467–472 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller GH, Kirk RW, Scott DW, Miller WH, Griffin CE. 2001. Muller and Kirk's small animal dermatology, 6th ed, p 1066–1071 Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller SA. 1990. Trichotillomania: a histopathologic study in 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 23:56–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mundy NI, Ancrenaz M, Wickings EJ, Lunn PG. 1998. Protein deficiency in a colony of Western Lowland gorillas (Gorilla g. gorilla). J Zoo Wildl Med 29:261–268 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newcomer CE, Fox JG, Taylor RM, Smith DE. 1984. Seborrheic dermatitis in a rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Lab Anim Sci 34:185–187 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novak MA, Meyer JS. 2009. Alopecia: possible causes and treatments, particularly in captive nonhuman primates. Comp Med 59:18–26 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ovadia S, Wilson SR, Zeiss CJ. 2005. Successful cyclosporine treatment for atopic dermatitis in a rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). Comp Med 55:192–196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasmussen KM, Thenen SW, Hayes KC. 1979. Folacin deficiency and requirement in the squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciuresus). Am J Clin Nutr 32:2508–2518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandoz A, Koenig T, Kusnir D, Tausk FA. 2008. Psychocutaneous diseases. : Fitzpatrick TB, Wolff K, Goldsmith L, Katz S, Gilchrest B, Paller AS, Leffell DJ. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine, 7th ed New York (NY): McGraw–Hill Medical [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stefanato CM. 2010. Histopathology of alopecia: a clinicopathological approach to diagnosis. Histopathology 56:24–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinmetz HW, Kaumanns W, Dix I, Heistermann M, Fox M, Kaup FJ. 2006. Coat condition, housing condition, and measurement of faecal cortisol metabolites—a noninvasive study about alopecia in captive rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). J Med Primatol 35:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinmetz HW, Kaumanns W, Neimeier KA, Kaup FJ. 2005. Dermatologic investigation of alopecia in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). J Zoo Wildl Med 36:229–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swenerton H, Hurley LS. 1980. Zinc deficiency in rhesus and bonnet monkeys, including effects on reproduction. J Nutr 110:575–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yearley JH, Pearson C, Carville A, Shannon RP, Mansfield KG. 2006. SIV-associated myocarditis: viral and cellular correlates of inflammation severity. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 22:529–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]