Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) is responsible for significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. Even after successful microbiological cure of TB, many patients are left with residual pulmonary damage that can lead to chronic respiratory impairment and greater risk of additional TB episodes due to reinfection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Elevated levels of the proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α and several other markers of inflammation, together with expression of matrix metalloproteinases, have been associated with increased risk of pulmonary fibrosis, tissue damage, and poor treatment outcomes in TB patients. In this study, we used a rabbit model of pulmonary TB to evaluate the impact of adjunctive immune modulation, using a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor that dampens the innate immune response, on the outcome of treatment with the antibiotic isoniazid. Our data show that cotreatment of M. tuberculosis infected rabbits with the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor CC-3052 plus isoniazid significantly reduced the extent of immune pathogenesis, compared with antibiotic alone, as determined by histologic analysis of infected tissues and the expression of genes involved in inflammation, fibrosis, and wound healing in the lungs. Combined treatment with an antibiotic and CC-3052 not only lessened disease but also improved bacterial clearance from the lungs. These findings support the potential for adjunctive immune modulation to improve the treatment of pulmonary TB and reduce the risk of chronic respiratory impairment.

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is one of the leading infectious disease causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Although current multidrug regimens are generally effective, treatment is lengthy, requiring a minimum of 6 months and sometimes more than 1 year, for patients with drug-resistant TB or other clinical complications.1 Even after successful microbiological cure, pulmonary TB patients are often left with residual lung damage.2–5 Pulmonary impairment after TB treatment has been observed as changes in the structure and function of bronchial parenchymal tissue and the persistence of fibrocavitary lung damage.6,7 The risk and the extent of chronic respiratory dysfunction in individuals after curative therapy have been shown to increase with the number of previous TB episodes.8 Most importantly, one recent study in South Africa found a fourfold higher risk of TB due to reinfection in previously treated patients compared with incidence rates among new TB cases.9

TB is primarily a disease of the lungs.10 Ingestion of inhaled M. tuberculosis by alveolar macrophages and/or dendritic cells of the lung induce the secretion of cytokines and chemokines, which activate the macrophages and orchestrate the recruitment of additional immune cells from the circulation to the site of infection. The accumulation of mononuclear leukocytes around the infected macrophages leads to formation of a layered cellular structure, known as a granuloma. As the granuloma grows, the macrophages differentiate into epithelioid cells, surrounded by T lymphocytes and B cells/plasma cells.11 In large progressive granulomas, the central cellular mass may undergo necrosis, characterized by formation of caseum that can liquefy and drain through a bronchus, resulting in cavity formation, which facilitates efficient transmission of the bacilli. The progressive granulomatous process is ultimately associated with extensive tissue necrosis and fibrosis.

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), produced by activated macrophages and other cells of the immune system, is one of the main proinflammatory cytokines involved in the host immune response to M. tuberculosis infection. Together with interferon gamma, TNF-α is essential for activating macrophages, rendering the cells better capable of controlling the intracellular growth of M. tuberculosis.12 However, the cytokine also drives the pathological process in the granulomas, leading to cell necrosis and irreversible tissue destruction.13 Consequently, there has been some interest in identifying immune modulators that reduce TNF-α production as a means to limit inflammation and improve treatment outcome in TB patients.14,15 For example, thalidomide has been shown to reduce TNF-α production in patients with pulmonary TB and to improve treatment outcome.16,17 To overcome the adverse effects of thalidomide, including teratogenicity and peripheral neuropathy, Celgene Corporation has synthesized a series of new chemical entities that inhibit TNF-α.18 One class of these compounds modulates the innate immune response by inhibiting phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4), an enzyme involved in regulating intracellular levels of cAMP in monocytes and macrophages.19 Celgene's PDE4 inhibitors have been shown to be nonteratogenic and well tolerated by humans as an anti-inflammatory agent in phase 1 clinical studies.20 CC-3052 is one of these PDE4 inhibitors; it is approximately 200-fold more potent than thalidomide in inhibiting TNF-α production by activated macrophages in vitro.21

We have previously established a model of progressive pulmonary TB in the rabbit by infecting animals via the respiratory route with the M. tuberculosis strain HN878.22 The infected rabbits in this model reflect most of the pathological characteristics of human pulmonary TB, including caseation, liquefaction, cavity formation and calcification of granulomas, and the development of fibrosis around the lesions.23 In the present study, we used the rabbit pulmonary TB model to investigate the effect of immune modulation with CC-3052 on the response to treatment with the antibiotic isoniazid (INH). M. tuberculosis infected rabbits were treated with INH in the presence and absence of adjunctive CC-3052, and the extent of immune pathogenesis in the different treatment groups was compared based on histologic analysis and the expression pattern in the lungs of a subset of host genes that are functionally associated with inflammation and/or wound healing and tissue remodeling.

Materials and Methods

Bacteria and Chemicals

M. tuberculosis HN878 (a gift from Dr. James Musser, Houston, TX) was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 media (Difco Laboratories Inc, Detroit, MI) supplemented with 0.5% glycerol, 10% OADC (oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, and catalase; BD Biosciences, Rockville, MD), and 0.25% Tween 80 until mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.5−0.7). Aliquots of stock cultures were stored at −80°C until use. The bacterial inoculum for aerosol infection was prepared from frozen stock cultures as reported earlier.24 All chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated.

Rabbit Infections

Specific pathogen-free New Zealand white rabbits, approximately 2.5 kg, of either sex (Millbrook Farms, Concord, MA) were used as described previously.24 All animals underwent a 1-week period of adaptation after arrival at the animal facility. The rabbits were then infected with M. tuberculosis HN878, using a nose-only aerosol exposure system (CH Technologies Inc., Westwood, NJ). At 3 hours after exposure, the number of colony-forming units (CFU) in the lungs was approximately 3.2 log10. The infectious dose was previously established through dose-response calibration experiments. Rabbits are relatively resistant to M. tuberculosis infection and give rise to 1 granuloma per 50 to 200 bacilli, depending on the strain used for the infection.25 At the dose used, M. tuberculosis HN878 produces a progressive granulomatous response with well-defined granulomas at 4 weeks after infection.22 At defined time points (4, 8, and 12 weeks after infection), rabbits were sedated with a combination of ketamine and xylazine, were euthanized by Euthasol, and underwent necropsy. Lungs were aseptically removed from a group of at least 4 animals, per time point, for bacterial CFU assay, histopathologic examination, and isolation of host and bacterial RNA. The numbers of dorsal subpleural lesions were counted as a measure of gross disease. All procedures with the infected animals were performed in BioSafety Level 3 containment facilities, according to the protocols approved by the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Rabbit Treatment Regimens

Group 1: Antituberculosis Chemotherapy (INH) - INH was administered to rabbits at a dose of 50 mg/kg by gavage, using a flexible rubber feeding tube 5 days a week. INH treatment was started at 4 weeks after infection and continued until 12 weeks after infection.

Group 2: Immunomodulatory Drug (CC-3052) - A second group of rabbits received the PDE4 inhibitor CC-3052, obtained from Celgene Corporation. The compound was freshly prepared each day, in distilled water, and administered by gavage at a dose of 25 mg/kg, using a flexible rubber feeding tube, 5 days per week. The dose of CC-3052 used was previously established in mice and is comparable to the half maximal inhibitory concentration in this animal model.26 Treatment with CC-3052 started at 4 weeks after infection and continued until 12 weeks after infection.

Group 3: Combination Therapy (INH plus CC-3052) - A third group of rabbits received a combination of INH (50 mg/kg) plus CC-3052 (25 mg/kg) 5 days per week. Treatment was initiated concurrently at 4 weeks after infection and continued until 12 weeks after infection.

One group each of uninfected and infected but untreated rabbits served as controls.

CFU Assay

Bacterial loads in the lungs of the infected rabbits were evaluated by plating 10-fold serial dilutions of the organ homogenates onto Middlebrook 7H11 agar plates (BD Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 3 to 5 weeks. Colonies were counted, and results were expressed as number of CFU in the whole lung.

Histology and Morphometry

Formalin-fixed (Fisher Chemical, Whippany, NJ) lung tissues of infected rabbits (untreated or treated with CC-3052 or INH or both) were paraffin embedded and used for standard 5-μm sectioning. Tissue sections were stained with H&E for cellular composition or with acid-fast staining to visualize M. tuberculosis. Van Gieson and Gomori's 1-step trichrome stain were used to visualize fibrous (collagen and elastic fibers) deposition. Morphometric analysis of the numbers of granulomas in the sections and percentage of lung parenchyma involved in the disease was made using Sigmascan Pro Software (Systat Softwares Inc., San Jose, CA).

Total RNA Isolation From Rabbit Lungs

For isolation of total RNA from rabbit lungs, sections of lung tissue were homogenized thoroughly in 10 volumes (wt/vol) of TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), using a PolyTron homogenizer (Kinematica, Lucerne, Switzerland), followed by extraction with 0.3 volume of chloroform (vol/vol). After centrifugation, the cleared supernatant was mixed with precipitation solution and eluted through a column included in the NucleoSpin kit per the manufacturer's protocol (Macherey-Nagel GmbH, Duren, Germany). The extracted host RNA was subjected to DNaseI digestion before final purification using the same kit. The quality and quantity of the total RNA were estimated by agarose gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop (NanoDrop Products, Wilmington, DE).

Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Total RNA from rabbit lungs was subjected to cDNA synthesis using a Superscript III (Invitrogen) kit, as described.27 The cDNA was amplified with gene-specific primers and SYBR green mix (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) per the manufacturer's instructions in an MxPro4000 real-time PCR machine (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The DNA sequences of the primers used for real-time quantitative PCR are listed in Table 1. The CT for each amplified target gene was calculated using MxPro4000 software. Uniform baseline fluorescence was set for all of the genes in each experiment. The transcripts of the rabbit GAPDH gene were used to normalize the CT values of target genes. Fold change was calculated using the formula 2−ΔΔCT and represented as absolute transcript levels or as relative expression after normalization. Each experiment was repeated at least 3 times with RNA samples from four animals per group per time point.

Table 1.

List of Rabbit Genes and Primer Sequences Used in Real-Time Quantitative PCR

| Sequence no. | Gene | Primer | Sequence | NCBI accession no |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TNF-α | Forward | 5′-CTGAGTGACGAGCCTCTAGC-3′ | NM_001082263.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-TTCATGCCGTTGGCCAGCAG-3′ | |||

| 2 | CRP | Forward | 5′-GCCAGAGGCAAGCATTATTC-3′ | NM_001082265.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-CGTGTACTTCACCACGTACT-3′ | |||

| 3 | SPP1 | Forward | 5′-TCTCCTAACACCGCAGAATG-3′ | NM_001082194.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-TCTGTAAGCCACACTGTCAC-3′ | |||

| 4 | ARG1 | Forward | 5′-GGCATCTACATCACAGAAGC-3′ | NM_001082108.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-CTGTGTTCACCGTTCGAGTT-3′ | |||

| 5 | IL-4 | Forward | 5′-CCATGCACCAAGCTGATGAT-3′ | NM_001163177.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-TCCTTGAAGCACCAAGACAC-3′ | |||

| 6 | IL-8 | Forward | 5′-GCTTCGATGCCAGTGCATAA-3′ | NM_001082293.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-GGCAGAGTTCTCTTCCATCA-3′ | |||

| 7 | MMP1 | Forward | 5′-AATGGCTAAGGAAGGCCAAG-3′ | NM_001171139.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-ATCAGGATGATGCGAGTGAC-3′ | |||

| 8 | MMP2 | Forward | 5′-CCGATGTCCAGCGAGTAGAC-3′ | NM_001082209.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-CCATCTTCTTCTTCACCTCA-3′ | |||

| 9 | MMP3 | Forward | 5′-TCTACAACGCCTTCACAGAC-3′ | NM_001082280.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-CCATAGGCACTCCAGAGTTA-3′ | |||

| 10 | MMP9 | Forward | 5′-CGCCAGCTACGACAAGGACA-3′ | NM_001082203.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-AAGTGGTGGCACACCAGAGG-3′ | |||

| 11 | MMP12 | Forward | 5′-CCAACTGGCTGTGACCACAA-3′ | NM_001082771.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-AGCAGCCTCAATGCCTGAAG-3′ | |||

| 12 | MMP13 | Forward | 5′-TCTTGAGCTGGACTCATTGC-3′ | NM_001082037.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-GCAGGATTCAGAGGATGGTA-3′ | |||

| 13 | MMP14 | Forward | 5′-CCACAAGATGCCTCCTCAAC-3′ | NM_001082793.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-GTAGCCGTCCATCACTTGGT-3′ | |||

| 14 | GAPDH | Forward | 5′-GGCGTGAACCACGAGAAGTA-3′ | NM_001082253.1 |

| Reverse | 5′-TCCACAATGCCGAAGTGGTC-3′ |

NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Statistical Analysis

The independent Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric independent data was used for analysis (SPSS software; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant for all of the experiments.

Results

Effect of CC-3052 and INH Treatment on Lung Disease

To study the effect of immune modulation on disease in the lungs of rabbits, animals were infected by the respiratory route to implant approximately 3000 M. tuberculosis HN878 on day zero. Groups of infected rabbits were treated from 4 weeks after infection with INH alone (50 mg/kg per day), CC-3052 alone (25 mg/kg per day), or INH plus CC-3052 or left untreated for an additional 4 or 8 weeks (8 or 12 weeks after infection). Lungs were collected, and portions of the infected tissues were used to enumerate M. tuberculosis by the number of CFU. The growth curve of M. tuberculosis HN878 in the lungs of infected rabbits has been reported previously.22 In short, the bacterial counts in the lungs of untreated rabbits increased exponentially to approximately 7 log10 CFU up to 4 weeks after infection, then stabilized and remain essentially constant for the next 8 weeks. A similar curve of bacterial counts was observed in rabbits treated with CC-3052 alone, indicating that treatment for 4 and 8 weeks did not adversely affect the control of bacillary growth in the lungs (Table 2 and Subbian et al, manuscript submitted). After 4 weeks of INH administration (8 weeks after infection), the numbers of CFU in the lungs of treated rabbits had not been reduced significantly. By 8 weeks of INH monotherapy (12 weeks after infection), the bacillary load was reduced by approximately 1 log10 CFU compared with untreated animals. In contrast, the greatest reduction in CFU was seen in the lungs of rabbits cotreated with CC-3052 plus INH compared with untreated and CC-3052 treated (P = 0.02) or INH treated (P = 0.04) animals at 12 weeks after infection. These results indicate that adjunctive immune modulation with CC-3052 can improve INH-mediated killing of M. tuberculosis in infected rabbits and that treatment with the PDE4 inhibitor alone does not result in uncontrolled bacillary growth in the lungs (Table 2 and Subbian et al, manuscript submitted). Importantly, addition of up to 50× molar excess of CC-3052 and 0.2 μg/mL of INH to an in vitro grown M. tuberculosis culture did not affect the growth significantly (Subbian et al, manuscript submitted). Thus, the impact of CC-3052 treatment on M. tuberculosis, either by itself or in combination with INH, appears to be specific to the in vivo conditions prevailing in the lungs of infected rabbits.

Table 2.

Bacillary Load in the Lungs of M. tuberculosis Infected Rabbit

| Time after infection | Untreated |

CC-3052 |

INH |

INH plus CC-3052 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |

| Day 1 | 3.2 (n = 11) | 0.17 | ||||||

| 4 weeks | 7.3 (n = 8) | 0.43 | ||||||

| 8 weeks | 6.7 (n = 10) | 0.46 | 7.0 (n = 11) | 0.67 | 7.2 (n = 6) | 0.76 | 6.4 (n = 5)⁎ | 0.04 |

| 12 weeks | 6.4 (n = 6) | 1.9 | 6.8 (n = 6) | 0.91 | 5.3 (n = 6) | 0.45 | 4.4 (n = 6)⁎ | 0.71 |

IQR, interquartile range.

Values are in log10 scale.

P < 0.05 between INH and INH plus CC-3052.

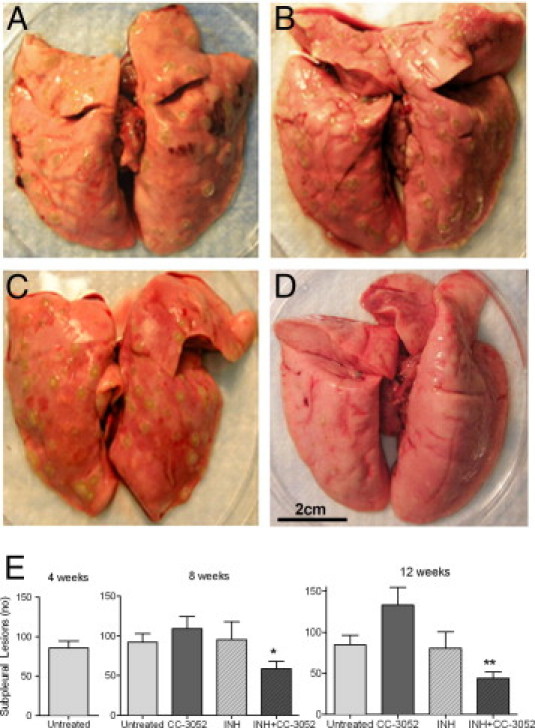

The development of granulomas in the lungs of the same animals was evaluated over time (Figure 1, A–E). Whole rabbit lungs from the four treatment groups (CC-3052 alone, INH alone, INH plus CC-3052, and no treatment) were examined for gross disease at 4, 8, and 12 weeks after infection, and the numbers of visible dorsal subpleural lesions were enumerated (Figure 1). The total number of subpleural lesions counted on the lungs of untreated animals was approximately 80 at 4 weeks after infection and did not change significantly at 8 and 12 weeks after infection (Figure 1E). Treatment with CC-3052 alone resulted in somewhat larger and more numerous lesions compared with the untreated rabbits at both 8 and 12 weeks after infection; however, the differences were not statistically significant. The number of lung lesions in animals treated with INH alone for 4 and 8 weeks (ie, 8 and 12 weeks after infection) was slightly lower but not significantly different from that in untreated controls and CC-3052 treated rabbits. In contrast, treatment with the combination of INH plus CC-3052 significantly reduced the number of subpleural lesions at 8 and 12 weeks after infection in comparison to both the untreated and CC-3052 (P < 0.001) or INH alone treatment groups (P < 0.002). In addition, the lungs of animals treated with INH plus CC-3052 showed less indication of inflammation, appearing pink and smooth at 12 weeks after infection (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Effect of CC-3052 treatment on M. tuberculosis infected rabbit lung pathologic findings. A–D: Gross pathologic findings of rabbit lungs at 12 weeks after infection. A: Untreated. B: CC-3052 treated. C: INH treated. D: INH plus CC-3052 treated. E: Number of subpleural lesions (dorsally) at 4, 8, and 12 weeks after infection. Statistically significant differences in the numbers of lesions were observed between the animals treated with INH plus CC-3052 and INH alone at 8 (asterisk) and 12 (double asterisk) weeks, respectively (P ≤ 0.05).

Effect of CC-3052 and INH Treatment on Lung Histopathologic Findings: Morphometric Analysis

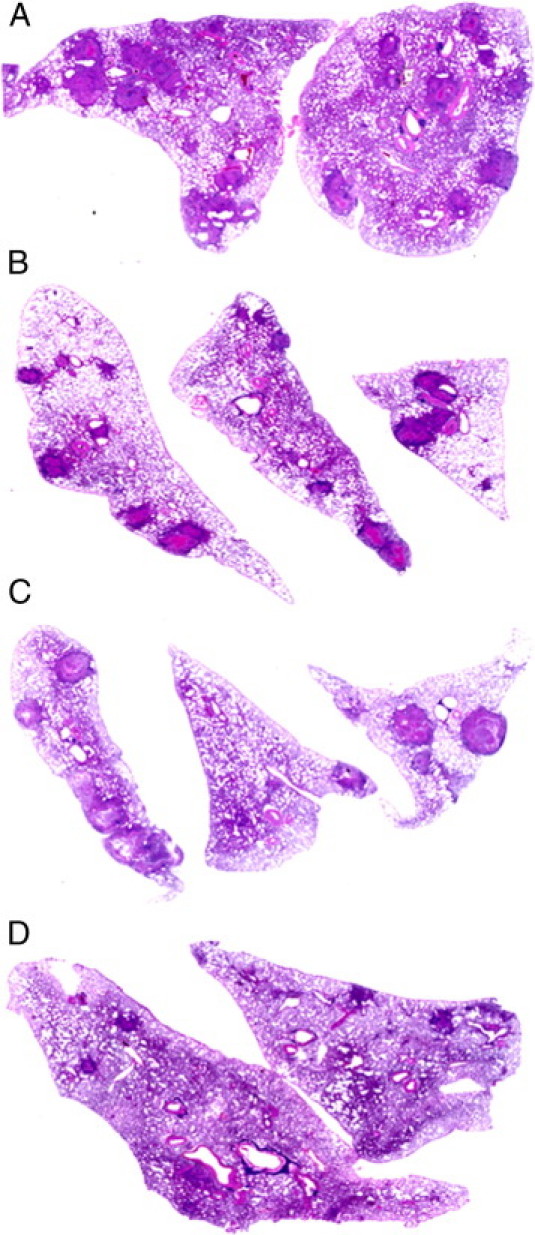

To obtain semiquantitative estimates of the impact of treatment on the histopathologic features in the lungs of infected rabbits, morphometric analysis of tissue sections was performed using Sigmascan Pro Software (Figure 2). At 4 weeks after infection, there was an average of 20/cm2 of granulomas in sections from the lungs of untreated rabbits, and this number did not significantly change for up to 12 weeks of infection (Figure 3A). A similar number of lesions were seen in the lung sections from rabbits treated with CC-3052 alone for 4 weeks. By 8 weeks of CC-3052 treatment, the number of lung lesions in this group had increased not significantly to approximately 25/cm2 lesions. Treatment with INH alone yielded slightly reduced numbers of lesions after 4 weeks (8 weeks after infection) and a larger reduction after 8 weeks of treatment, but the differences were not significant compared with untreated animals. In contrast, rabbits treated with INH plus CC-3052 showed a significant reduction in the number of lung lesions at 8 weeks after infection (4 weeks of treatment) compared with the three other treatment groups (P = 0.0006) and a further reduction at 12 weeks after infection (8 weeks of treatment) compared with the other treatment groups (P < 0.005).

Figure 2.

Morphometric analysis of scanned sections of the lungs of rabbits at 12 weeks after infection, stained with H&E. A: Untreated. B: CC-3052 treated. C: INH treated. D: CC-3052 plus INH treated. Rabbits treated with INH plus CC-3052 had a significantly lower extent of lung infiltration. P ≤ 0.05. Some sections had no granulomas.

Figure 3.

Morphometric measurement of the number of lesions (per square centimeters) and the percentage of the lung section occupied by granulomas in the M. tuberculosis infected rabbit lungs. A: Number of lung lesions. B: Extent of lung involvement. Statistically significant difference in the numbers of lesions observed between animals treated with INH plus CC-3052 and INH alone at 8 and 12 weeks after infection (asterisk). P ≤ 0.05.

Differences in the extent of lung involvement, as defined by the percentage of the area of the section that was occupied by granulomas, were also noted among the treatment groups (Figure 3B). At 4 weeks after infection, approximately 15% of the area of the lung sections was occupied by granulomas. In the untreated animals, the percentage of lung involvement was highest at 8 weeks and declined by 12 weeks after infection. In the CC-3052 alone group, lung involvement was similar to the untreated group at 8 weeks (4 weeks of treatment) but did not decline by 12 weeks after infection (8 weeks of treatment). Treatment with INH alone reduced the percentage of involved lung at 8 weeks to roughly 8%, with a slight further decline by 12 weeks after infection. The greatest reduction in lung involvement was noted in the lungs of rabbits treated with CC-3052 plus INH, which was significantly lower compared with the untreated and CC-3052 treated (P < 0.001) or INH treated (P = 0.03) animals at 8 weeks after infection (4 weeks of treatment). This difference in the extent of lung involvement was even more pronounced at 12 weeks after infection. At this time point, rabbits treated with the combination of INH plus CC-3052 had few small granulomas, indicating that the granulomas were undergoing resorption. In this group, most of the lung parenchyma was intact compared with untreated (P < 0.01), INH treated (P = 0.05), or CC-3052 treated (P < 0.001) animals, and a number of the lung sections had no lesions at all.

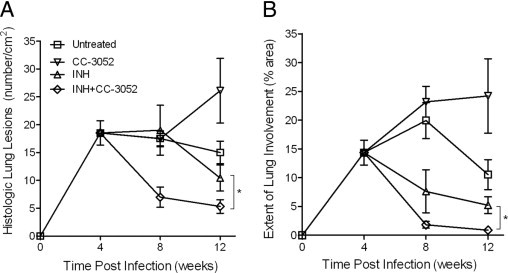

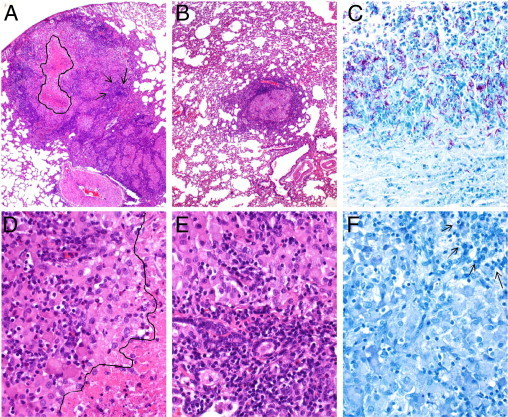

Effect of CC-3052 Plus INH Treatment on Lung Histopathologic Findings

Histopathologic analysis of the lungs of M. tuberculosis infected rabbits at 12 weeks after infection showed that untreated rabbits had multiple large coalescent granulomas, with varying amounts of central necrosis, surrounded by foamy macrophages and peripheral accumulation of lymphocytes and epithelioid macrophages (Figure 4, A and D). Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) were commonly seen in the borders of the necrotic areas and more extensively in association with initiation of liquefaction. In some of the lesions, extensive liquefaction (suppurative granulomas), fibrosis, and the formation of large cavities were observed (Figure 4, B and E). Cross-sections of the cavities showed concentric layers, with an extensive necrotic zone at the luminal surface of the cavity and a fibrotic area, adjacent to a highly cellular granulomatous layer containing large numbers of macrophages, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts. INH-treated rabbits had a similar number of somewhat smaller lesions compared with the untreated animals. The granulomas contained central areas of tissue breakdown and necrosis surrounded by foamy macrophages, with mixed epithelioid macrophages and lymphocytes in the periphery (Figure 4, C and F).

Figure 4.

Histopathology of M. tuberculosis infected rabbit lungs at 12 weeks after infection. A and D: Untreated rabbit. Large confluent granulomas with central necrosis (the area marked by drawing in A and the area under the line in D), surrounded by cuff of lymphocytes (arrows), are observed. B and E: Control untreated rabbit lung with a cavity (the opaque top left area in B and E). Note the layers from the cavity lumen out: an extensive necrotic zone (the area above the marked line in B), with numerous lymphocytes (arrows). The circled area in B is magnified to show the features in E. A fibrotic area adjacent to a highly cellular granulomatous layer is observed below the dotted line in E. C and F: Rabbit treated with INH alone. Large granulomas with central necrosis (the area marked by drawing in C and the area above the marked line in F) and areas of lymphocytes (arrows). Sections were stained with H&E and photographed at ×4 (A–C) or ×40 (D–F) magnification.

Animals treated with CC-3052 alone, at 12 weeks after infection, had the largest and most numerous lesions (Figure 5, A and D). These were highly cellular, containing fewer foamy macrophages and multiple aggregates of epithelioid macrophages surrounded by large numbers of lymphocytes. These lesions were similar to those described in control untreated rabbits at earlier time points (4 and 8 weeks).23 Thus, it appeared that the lung granulomas in the CC-3052 treated animals were less differentiated, more cellular, and larger than the granulomas of untreated infected rabbit lungs. Although some of the granulomas showed extensive necrosis, few cavities were observed in this treatment group. Although treatment with CC-3052 did not impair the control of bacillary growth, based on the bacillary CFU data, it appeared to dampen some component of the immune response responsible for limiting the extent of lung disease. However, the severity of the disease was not increased, as indicated by the observation that only 3.18% ± 3.86% of the area of the granulomas was necrotic in the CC-3052 treated rabbits, compared with 5.19% ± 9.49% in the control animals (estimated by morphometric analysis, data not shown). Moreover, lower numbers of PMNs were seen in the granulomas from CC-3052 treated animals compared with those from untreated animals. In contrast, fewer and smaller lesions were present in the rabbits treated with INH plus CC-3052 relative to the controls and other treatment groups (Figure 5, B and E). These lesions were seldom necrotic and contained a core of epithelioid macrophages surrounded by large numbers of lymphocytes. Acid-fast bacilli staining of the M. tuberculosis infected rabbit lung tissues revealed small numbers of organisms in the foamy macrophages of the granulomas of untreated and CC-3052 treated animals (not shown). In contrast, the granulomas with cavities had very large numbers of bacilli in the necrotic cell debris of the cavity lumen (Figure 5C). Few single acid-fast bacilli were found in the granulomas of INH treated animals and even fewer in the lesions of INH plus CC-3052 treated rabbits (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Histopathologic analysis of M. tuberculosis infected rabbit lungs at 12 weeks after infection. A and D: Rabbit treated with CC-3052 alone. Big confluent granulomas with central necrosis (the area marked by drawing in A and the area under the line in D) and large numbers of lymphocytes (arrows). B and E: Rabbit treated with the combination of INH plus CC-3052. Few small, well-organized granulomas with a central area of epithelioid macrophages and a peripheral cuff of lymphocytes. No necrosis was observed. C: Control untreated animal. Large number of acid-fast bacilli in the area adjacent to the cavity lumen and in the necrotic zone of the granuloma. F: Rabbit treated with INH plus CC-3052. No acid-fast bacilli can be seen in this section. Arrows indicate lymphocytes. Tissue sections were stained with H&E (A, B, D, and E) or acid-fast stain (C and F) and photographed at ×4 (A and B) or ×40 (C–F) magnification.

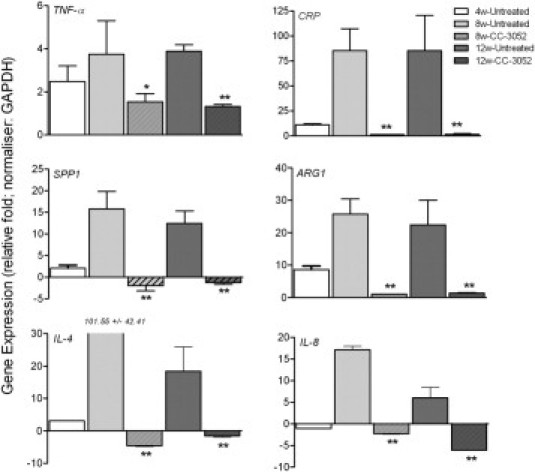

Effect of CC-3052 Treatment on Expression of Selected Host Genes Associated with Inflammation in the Lungs of M. tuberculosis-Infected Rabbits

Because PDE4 inhibition by CC-3052 has been shown to reduce TNF-α production, we analyzed the expression of selected biomarkers of tissue inflammation, including TNF-α. The selected genes included those encoding C-reactive protein (CRP), osteopontin (SPP1), and arginase 1 (ARG1), all of which have been associated with severity of disease either in TB patients or in animals models of the disease.28–31 In addition, expression of the cytokine genes encoding IL-4, which is involved in alternative macrophage activation and maintenance of TH1/TH2 balance during M. tuberculosis infection,32 and IL-8, which is associated with PMN recruitment and activation,33,34 was evaluated. Rabbit gene expression was determined by real-time quantitative PCR analysis of mRNA prepared from the lungs of M. tuberculosis infected animals that were untreated or treated with CC-3052 alone. The housekeeping gene GAPDH was used to normalize the expression of target genes. In the lungs of infected untreated rabbits, TNF-α mRNA levels were elevated at 4 weeks, relative to uninfected animals, then increased further at 8 weeks and maintained at the higher level to 12 weeks after infection (Figure 6). Similar expression patterns were noted for CRP, SPP1, and ARG1, which were low but detectable at 4 weeks, significantly increased at 8 weeks, and remained elevated to 12 weeks after infection. In contrast, the levels of IL-4 and IL-8 mRNAs were low at 4 weeks, then peaked at high levels at 8 weeks and decreased by 12 weeks after infection. Importantly, CC-3052 treatment resulted in significantly reduced expression of TNF-α at both 8 and 12 weeks of M. tuberculosis infection (Figure 6). Inhibition of TNF-α by CC-3052 treatment was associated with 12- to 75-fold reductions in the expression of ARG1, SPP1, and CRP. Similarly, IL-4 and IL-8 mRNAs were reduced more than 110-fold and more than 30-fold, respectively, after 4 and 8 weeks of treatment (8 and 12 weeks after infection) (Figure 6). These observations suggest that the modulation of the rabbit immune response by CC-3052 dampened the host inflammatory response at the level of mRNA expression, as indicated by the down-regulation of genes encoding diverse soluble markers known to be involved in acute inflammation, alternative macrophage activation, and tissue fibrosis.

Figure 6.

Expression of rabbit genes differentially regulated by CC-3052 treatment. Expression of individual genes was quantified by real-time quantitative PCR, normalized against the housekeeping gene GAPDH, and represented as relative fold (log10) compared with the expression levels in uninfected, naive rabbits. Expression level of each gene was measured in triplicates in at least 3 different experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 between CC-3052 treated and untreated animals.

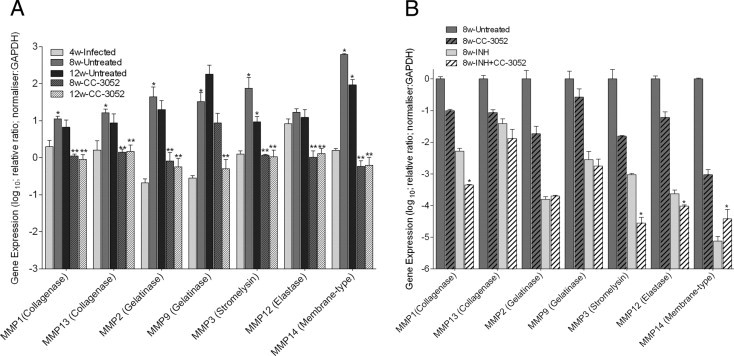

Effect of CC-3052 Treatment on Host Matrix Metalloproteinase Gene Expression in M. tuberculosis-Infected Rabbit Lungs

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) comprise a family of enzymes, which includes collagenases (eg, MMP1 and MMP13), gelatinases (eg, MMP2 and MMP9), stromelysins (eg, MMP3), elastases (eg, MMP12), and membrane-type proteases (eg, MMP14), that are involved in connective tissue homeostasis and remodeling. MMPs are key players in the fibrotic process associated with chronic inflammation and granuloma formation (active TB disease), as well as in resorption of disease and wound healing (repair, connective tissue replacement) during M. tuberculosis infection.35,36 Because TNF-α is involved in granuloma formation and maintenance and has been implicated in the regulation of some MMPs,37–39 we evaluated the impact of CC-3052 immune modulation on the expression of several MMPs by real-time quantitative PCR. We compared the levels of MMP1, MMP13, MMP2, MMP9, MMP3, MMP12, and MMP14 mRNAs in the lungs of M. tuberculosis infected rabbits that were untreated or treated with CC-3052 alone. At 4 weeks of infection, all of these MMP genes were significantly induced in the lungs of infected untreated rabbits, relative to uninfected animals. The expression levels of the collagenase genes MMP1 and MMP13 and gelatinase MMP2 in the untreated animal lungs significantly increased up to 8 weeks and then plateaued by 12 weeks after infection (Figure 7A). Gelatinase MMP9 mRNA levels continued to increase up to 12 weeks after infection. The expression of both stromelysin MMP3 and membrane-type protease MMP14 were significantly increased at 8 weeks and then declined slightly at 12 weeks after infection. Elastase MMP12 expression was induced by 4 weeks and continued at the same levels up to 12 weeks after infection. CC-3052 treatment abrogated the infection-induced expression of all of the tested MMPs at both 8 and 12 weeks after infection (Figure 7A). With the exception of MMP9 at 8 weeks, the MMP genes in the lungs of CC-3052 treated animals at 8 and 12 weeks were expressed at levels similar to or lower than those observed in the rabbits at 4 weeks after infection (before treatment initiation). Overall, the pattern of MMP gene expression in response to CC-3052 treatment reflects potential reduction in progressive inflammation and a dampening of fibrosis and/or tissue remodeling.

Figure 7.

Expression of MMP genes in M. tuberculosis infected rabbit lungs with and without CC-3052 treatment (A) or with INH alone or INH plus CC-3052 (B). Expression of individual genes was quantified by real-time quantitative PCR, normalized against the housekeeping gene GAPDH, and represented as relative fold (log10) compared with the expression levels in uninfected, naive rabbit lungs (A) or relative to 8-week untreated rabbits (B). Expression level of each gene was measured in triplicates in at least 3 different experiments. A: *P < 0.05 between 4 weeks and 8 and/or 12 weeks for untreated samples; **P < 0.05 between CC-3052 treated and untreated samples. B: *P < 0.05 between INH alone and INH plus CC-3052 treated samples.

Effect of INH Plus CC-3052 Treatment on Host MMP Gene Expression in M. tuberculosis-Infected Rabbit Lungs

Because expression of MMP genes is essential for the processes of wound healing and tissue repair, we measured the expression of MMP1, MMP2, MMP3, MMP9, MMP12, MMP13, and MMP14 in the lungs of M. tuberculosis infected rabbits in response to INH treatment alone or in combination with CC-3052. Because the expression of most of the selected MMP genes peaked at 8 weeks of M. tuberculosis infection, the analysis was performed at this time point (Figure 7B). Interestingly, INH treatment significantly reduced the expression of all of the tested MMP genes compared with the untreated controls. The reduction was highest for MMP14 (approximately 5 log10), followed by MMP12, MMP2 (approximately 4 log10), MMP3, MMP9 (approximately 3 log10), MMP1 (approximately 2 log10), and MMP13 (approximately 1 log10). In rabbits cotreated with INH plus CC-3052, the expression levels of MMP1, MMP3, and MMP12 were further significantly reduced compared with treatment with INH alone. In contrast, the expression levels of MMP2, MMP9, and MMP13 were comparable and not significantly different between the two treatment groups. Only the expression of the membrane-type metalloproteinase MMP14 showed higher levels in the INH plus CC-3052 group compared with the INH alone group (Figure 7B). In summary, the findings suggest that INH treatment results in dampening of the infection-induced expression of MMP1, MMP2, MMP3, MMP9, MMP12, MMP13, and MMP14 in the lungs of infected rabbits and that CC-3052 coadministration further reduced the expression of selected genes (MMP1, MMP3, MMP12, and MMP14). This differential regulation of the MMP gene expression between the animals treated with INH and INH plus CC-3052 may explain the improved resorption of the granulomas in the lungs of the cotreated animals seen at 8 and 12 weeks after infection.

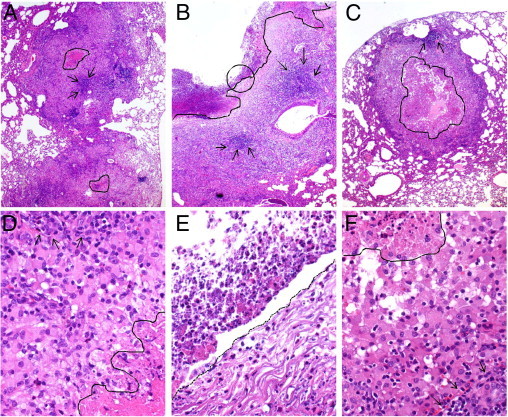

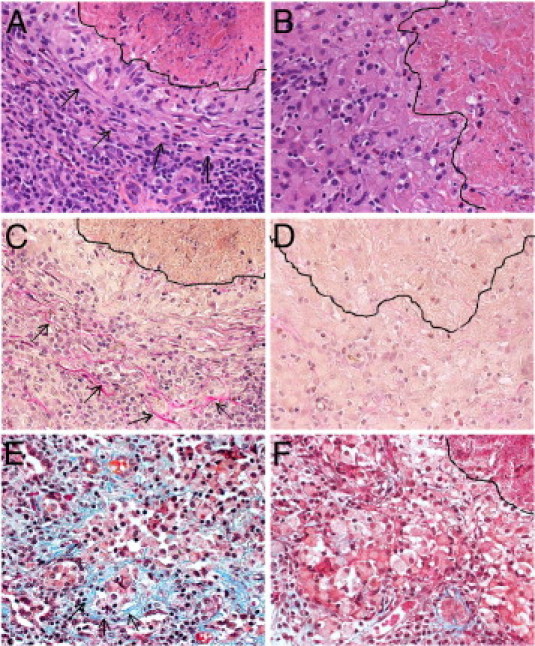

Effect of CC-3052 Treatment on the Lung Fibrosis in M. tuberculosis-Infected Rabbits

To evaluate the extent of the fibrotic process in the lungs of M. tuberculosis infected rabbits in the four treatment groups, Van Gieson and Gomori's trichrome stained sections of the lungs were examined. Little to no fibrosis was seen in the tissues at 4 or 8 weeks after infection (not shown). At 12 weeks after infection, considerable collagen deposition was seen around the granulomas and adjacent to their necrotic centers in the lungs of untreated animals (Figure 8, A, C, and E). In contrast, the lungs of animals treated with CC-3052 contained granulomas with minimal amounts of fibrosis (Figure 8, B, D, and F). Granulomas from the rabbit lungs treated with INH and INH plus CC-3052 showed even lower levels of fibrosis (not shown). Taken together, our findings suggest that the histopathology observation of tissue fibrosis in the lungs of untreated rabbits could be associated with elevated levels of MMP gene expression. Moreover, the reductions in MMP gene expression due to CC-3052 treatment correlated with less fibrosis in and around the granulomas.

Figure 8.

Extent of fibrosis in M. tuberculosis infected rabbit lung tissue from an untreated (A, C, and E) rabbit or an animal treated with CC-3052 (B, D, and F) at 12 weeks after infection. The layered appearance of the fibroblasts below the necrotic center (the area above the marked line) of a granuloma is seen in A (arrows). In contrast, the cells are more loosely aggregated in B and F (the area on the left side of the marked line). A fine network of extracellular matrix components, including collagen, can be clearly visualized by the pink staining in the Van Gieson (arrows in C) and the blue staining in the Gomori's trichrome (arrows in E) stained sections of lungs from untreated animals infected with M. tuberculosis. Less staining is seen in the granulomas of the CC-3052 treated rabbits (D and F). Sections were stained with H&E (A and B) or Van Gieson stain (C and D) or Gomori's trichrome stain (E and F) and photographed at ×40 magnification.

Discussion

Using a rabbit pulmonary TB model, we demonstrated that modulation of the host immune response with a PDE4 inhibitor results in an enhanced response to INH therapy, with a striking improvement in the resorption of lung granulomas. The PDE4 inhibitor, CC-3052, achieved this effect without generalized immune suppression, which can lead to disseminated TB. Moreover, although CC-3052 treatment, in the absence of antibiotics, delayed the maturation and resorption of the lung granulomas, it did not adversely affect the ability of the rabbits to control bacillary growth in the lungs. These results confirm similar observations made in the murine model of low-dose aerosol infection, where CC-3052 treatment in combination with INH improved M. tuberculosis clearance and reduced the extent of lung involvement, compared with treatment with INH alone.26 However, the improved lung disease was more striking in the rabbits because, unlike in mice, the granulomatous response in rabbits is similar to that seen in the lungs of humans with TB.23 In addition, treatment of M. tuberculosis in vitro with up to 50× molar excess of CC-3052 did not show any bactericidal or bacteriostatic effect.

A number of soluble immunologic mediators have been associated with severity of disease and poor outcome in patients with TB. Previous studies have shown that the induction of chemokines and proinflammatory cytokines, particularly TNF-α, by M. tuberculosis infection can cause profound local tissue inflammation and destruction at the sites of infection.40,41 Circulating levels of TNF-α in the serum of patients with severe TB have been correlated with clinical deterioration and poor treatment outcome.42 An association between TNF-α expression and the occurrence of necrosis in lesions from HIV-positive TB patients has been reported.43 In addition, several studies using animal infection models of TB have demonstrated the adverse effects of excessive TNF-α production on disease.44,45 In the present study, adjunctive treatment of M. tuberculosis infected rabbits with CC-3052 and INH significantly reduced the level of TNF-α mRNA expression and was associated with a marked reduction in the extent of lung disease. IL-4 expression is associated with the alternative activation of macrophages, and elevated levels of this cytokine have been correlated with both delayed response to treatment46 and greater risk of cavitary disease47 in TB patients. Infection with more virulent M. tuberculosis strains (such as the W-Beijing strain HN878 used in this study) leads to greater IL-4 production than infections with less virulent strains in vitro48 and in vivo.49,50 IL-8 (CXCL8) recruits neutrophils to the site of infection in M. tuberculosis infected guinea pigs34 and is elevated in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids from TB patients.33,51,52 CRP is often routinely monitored as a clinical marker of inflammation. TB patients show elevated serum levels of this protein, which decline with favorable response to treatment.46 Levels of mRNA expression of all of these markers were reduced in M. tuberculosis infected rabbits in response to CC-3052 treatment, supporting the potential benefits of this intervention.

Osteopontin, encoded by SPP1, produced by macrophages and T cells, is up-regulated in inflammatory pleural infusions53 and plays a critical role in granuloma formation in TB.54 High plasma levels of the protein in TB patients were found to correlate with treatment outcome30,55 and the extent of lung lesions.29 A recent study showed osteopontin in association with inflammation, fibrosis, and scarring in a mouse model of wound healing.56 The product of the ARG1 gene, arginase 1, is produced together with gelatinase by neutrophils in response to TNF-α stimulation to promote tissue regeneration in TB.57 Arginase 1 limits the production of nitric oxide by macrophages and is induced by M. tuberculosis and Toxoplasma gondii, two organisms associated with chronic infection.31 Dampened ARG1 expression has been associated with higher NO production by macrophages and better M. tuberculosis control.31 These markers were also inhibited by CC-3052 treatment. Taken together, these observations suggest that macrophage activation was dampened by CC-3052 treatment, reducing the inflammatory damage caused by soluble mediators released by the cells when they are maximally activated. Future studies will address the effect of CC-3052 treatment on the expression of other rabbit genes that encode for cytokines, chemokines, and signaling molecules that are known to be involved in macrophage activation after infection with M. tuberculosis.

Reduced inflammation during CC-3052 treatment was associated with a decrease in the extent of fibrosis in the granulomas of the M. tuberculosis infected rabbit lungs. The MMP family of proteolytic enzymes is primarily involved in the breakdown and remodeling of extracellular matrix during chronic granulomatous diseases and wound healing.58,59 Mice infected with M. tuberculosis have increased levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in infected tissues.60 In TB patients, serum levels of MMP-9 have been correlated with disease severity,61 and one study has shown an association between a promoter polymorphism in MMP-1 and increased risk of fibrosis after pulmonary TB.62 MMP activity may contribute to the extravasation of infected macrophages from the alveolar space into capillaries, thereby facilitating dissemination of mycobacteria around the body and exacerbating disease.63,64 MMP-mediated extracellular matrix degradation is one of the key factors in liquefaction and cavitation in the lungs of TB patients,38,58 and one recent study showed that M. tuberculosis drives excess MMP-9 secretion by pulmonary epithelial cells, causing tissue destruction.65 MMP production has been reported to be induced by cell death (necrosis).52 On TNF-α–mediated macrophage activation, as seen during M. tuberculosis infection, several MMPs have been shown to be induced in vivo and in vitro.66–69 In our study, the induction of MMP and ARG1 expression in the lungs of M. tuberculosis infected rabbits correlated with increased cellular necrosis, as well as PMN accumulation and cell death, at the center of the granuloma. In rabbits treated with CC-3052, reduced MMP and ARG1 expression was associated with more limited necrosis and lower numbers of PMNs in the centers of the granulomas. Interestingly, a homologue of MMP1, a prominent type I collagenase expressed in the caseating granulomas of human TB, is present in the rabbit genome but absent in that of mice. This difference has been suggested as the underlying reason for the lack of caseation and cavitation of mouse granulomas during M. tuberculosis infection.35,36 Further experiments are necessary to elucidate the specific links between TNF-α, MMP induction, PMN accumulation, cavity formation, and tissue remodeling in rabbit granulomas during M. tuberculosis infection. Although changes in mRNA levels address the regulation of gene expression at the transcriptional level, specific activity of proteins, such as MMPs, involves posttranslational modifications and activation.70 However, standardized assay procedures to measure the enzymatic activity of MMP in rabbit tissues are not currently available but are under development (William Bishai, personal communication).

Importantly, CC-3052 treatment was not the only cause of reduced MMP expression in our study. Treatment of M. tuberculosis infected rabbits with INH alone also reduced the expression of MMP genes. Because INH did not significantly reduce the bacillary load in the lungs of infected rabbits after 4 weeks of treatment (ie, 8 weeks after infection), we assume that the drug reduced inflammation in the lungs of treated rabbits by an as yet unknown mechanism. INH targets mycobacterial enzymes involved in cell wall synthesis.71 Therefore, it is possible that the drug modified the synthesis of M. tuberculosis cell wall components that contribute to local inflammation, triggering alterations in host gene expression, including those encoding for MMP.35,58 The combination of antibiotic plus immune modulator, such as INH plus CC-3052 used in this study, had a profound impact on limiting the extent of inflammation and, consequently, on the amount of tissue damage. It is also possible that reduced fibrosis in the presence of CC-3052 may have improved the penetration of INH into the granulomatous lesions, thereby enhancing antimicrobial killing. In the future, we plan to perform pharmacokinetic studies to compare the INH levels inside individual granulomatous lesions of CC-3052 treated and untreated rabbits. These results should clarify the impact of fibrosis on INH availability within the granulomas.

Because the CC-3052 treatment reduces the TNF-α level but does not completely eliminate the production and/or the release of the cytokine, the drug did not lead to general immune suppression in the rabbits. This is important because TNF-α is essential for an effective protective immune response against M. tuberculosis infection.72,73 Treatment of patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, with TNF-α neutralizing drugs is accompanied by a significantly increased risk of reactivation of latent (asymptomatic) M. tuberculosis infection.74,75 In contrast, several PDE4 inhibitors have shown positive results in human clinical trials for the treatment of other inflammatory lung diseases, including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.76 Our results show that adjunctive immune modulation with a PDE4 inhibitor could provide a means to improve clinical outcome in the absence of significant immune suppression or other toxic effects. A similar approach could be applied to TB patients to accelerate bacillary clearance and improve clinical outcome by limiting residual pulmonary damage after successful microbiological cure.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Drs. Claudia Manca, Veronique Dartois, and Helena Boshoff for their interest and valuable suggestions.

Footnotes

Supported by a TB Drug Accelerator Grant from The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (RO1 54338 to G.K.).

S.S. and L.T. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: J.Z. and G.M. are employed by Celgene Corporation. G.K. is a member of the board of Celgene Corporation. The compound CC-3052 used in these studies was provided by Celgene Corporation free of charge. Celgene Corporation had no role in study design, data collection, or analysis. The other authors declare no competing interest.

References

- 1.Treatment of tuberculosis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:1–77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Valliere S., Barker R.D. Residual lung damage after completion of treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:767–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasipanodya J.G., Miller T.L., Vecino M., Munguia G., Garmon R., Bae S., Drewyer G., Weis S.E. Pulmonary impairment after tuberculosis. Chest. 2007;131:1817–1824. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park J.H., Na J.O., Kim E.K., Lim C.M., Shim T.S., Lee S.D., Kim W.S., Kim D.S., Kim W.D., Koh Y. The prognosis of respiratory failure in patients with tuberculous destroyed lung. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:963–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross J., Ehrlich R.I., Hnizdo E., White N., Churchyard G.J. Excess lung function decline in gold miners following pulmonary tuberculosis. Thorax. 2010;65:963–967. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.129999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plit M.L., Anderson R., Van Rensburg C.E., Page-Shipp L., Blott J.A., Fresen J.L., Feldman C. Influence of antimicrobial chemotherapy on spirometric parameters and pro-inflammatory indices in severe pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:351–356. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long R., Maycher B., Dhar A., Manfreda J., Hershfield E., Anthonisen N. Pulmonary tuberculosis treated with directly observed therapy: serial changes in lung structure and function. Chest. 1998;113:933–943. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.4.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hnizdo E., Singh T., Churchyard G. Chronic pulmonary function impairment caused by initial and recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis following treatment. Thorax. 2000;55:32–38. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verver S., Warren R.M., Beyers N., Richardson M., van der Spuy G.D., Borgdorff M.W., Enarson D.A., Behr M.A., van Helden P.D. Rate of reinfection tuberculosis after successful treatment is higher than rate of new tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1430–1435. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1200OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honer zu Bentrup K., Russell D.G. Mycobacterial persistence: adaptation to a changing environment. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:597–605. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samuelson J. Infectious diseases. In: Cotran R.S., Kumar V., Collins T., editors. vol 6. W.B. Saunders Company; Philadelphia, PA: 1999. pp. 349–352. (Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease). ch 8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan G., Freedman V.H. The role of cytokines in the immune response to tuberculosis. Res Immunol. 1996;147:565–572. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(97)85223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cerami A., Beutler B. The role of cachectin/TNF in endotoxic shock and cachexia. Immunol Today. 1988;9:28–31. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(88)91353-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Churchyard G.J., Kaplan G., Fallows D., Wallis R.S., Onyebujoh P., Rook G.A. Advances in immunotherapy for tuberculosis treatment. Clin Chest Med. 2009;30:769–782. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ix

- 15.Wallis R.S. Reconsidering adjuvant immunotherapy for tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:201–208. doi: 10.1086/430914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tramontana J.M., Utaipat U., Molloy A., Akarasewi P., Burroughs M., Makonkawkeyoon S., Johnson B., Klausner J.D., Rom W., Kaplan G. Thalidomide treatment reduces tumor necrosis factor alpha production and enhances weight gain in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Mol Med. 1995;1:384–397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bekker L.G., Haslett P., Maartens G., Steyn L., Kaplan G. Thalidomide-induced antigen-specific immune stimulation in patients with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:954–965. doi: 10.1086/315328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller G.W., Corral L.G., Shire M.G., Wang H., Moreira A., Kaplan G., Stirling D.I. Structural modifications of thalidomide produce analogs with enhanced tumor necrosis factor inhibitory activity. J Med Chem. 1996;39:3238–3240. doi: 10.1021/jm9603328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corral L.G., Muller G.W., Moreira A.L., Chen Y., Wu M., Stirling D., Kaplan G. Selection of novel analogs of thalidomide with enhanced tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitory activity. Mol Med. 1996;2:506–515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottlieb A.B., Strober B., Krueger J.G., Rohane P., Zeldis J.B., Hu C.C., Kipnis C. An open-label, single-arm pilot study in patients with severe plaque-type psoriasis treated with an oral anti-inflammatory agent, apremilast. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:1529–1538. doi: 10.1185/030079908x301866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marriott J.B., Westby M., Cookson S., Guckian M., Goodbourn S., Muller G., Shire M.G., Stirling D., Dalgleish A.G. CC-3052: a water-soluble analog of thalidomide and potent inhibitor of activation-induced TNF-alpha production. J Immunol. 1998;161:4236–4243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flynn J., Tsenova L., Izzo A., Kaplan G. Experimental Animal Models of Tuberculosis. In: Britton S.H., editor. Handbook of Tuberculosis: Immunology and Cell Biology. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmBH & Co. KGaA; Weinheim, Germany: 2008. pp. 389–426. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan G., Tsenova L. Pulmonary Tuberculosis in the Rabbit: A Color Atlas of Comparative Pathology of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. In: Leong F.J., Dartois V., Dick T., editors. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; Boca Raton, FL: 2010. pp. 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsenova L., Harbacheuski R., Moreira A.L., Ellison E., Dalemans W., Alderson M.R., Mathema B., Reed S.G., Skeiky Y.A., Kaplan G. Evaluation of the Mtb72F polyprotein vaccine in a rabbit model of tuberculous meningitis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2392–2401. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2392-2401.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manabe Y.C., Dannenberg A.M., Jr., Tyagi S.K., Hatem C.L., Yoder M., Woolwine S.C., Zook B.C., Pitt M.L., Bishai W.R. Different strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cause various spectrums of disease in the rabbit model of tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6004–6011. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.6004-6011.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koo M.S., Manca C., Yang G., O'Brien P., Sung N., Tsenova L., Subbian S., Fallows D., Muller G., Ehrt S., Kaplan G. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibition reduces innate immunity and improves isoniazid clearance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the lungs of infected mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subbian S., Mehta P.K., Cirillo S.L., Cirillo J.D. The Mycobacterium marinum mel2 locus displays similarity to bacterial bioluminescence systems and plays a role in defense against reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Djoba Siawaya J.F., Bapela N.B., Ronacher K., Veenstra H., Kidd M., Gie R., Beyers N., van Helden P., Walzl G. Immune parameters as markers of tuberculosis extent of disease and early prediction of anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy response. J Infect. 2008;56:340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inomata S., Shijubo N., Kon S., Maeda M., Yamada G., Sato N., Abe S., Uede T. Circulating interleukin-18 and osteopontin are useful to evaluate disease activity in patients with tuberculosis. Cytokine. 2005;30:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koguchi Y., Kawakami K., Uezu K., Fukushima K., Kon S., Maeda M., Nakamoto A., Owan I., Kuba M., Kudeken N., Azuma M., Yara S., Shinzato T., Higa F., Tateyama M., Kadota J., Mukae H., Kohno S., Uede T., Saito A. High plasma osteopontin level and its relationship with interleukin-12-mediated type 1 T helper cell response in tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1355–1359. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200209-1113OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El Kasmi K.C., Qualls J.E., Pesce J.T., Smith A.M., Thompson R.W., Henao-Tamayo M., Basaraba R.J., Konig T., Schleicher U., Koo M.S., Kaplan G., Fitzgerald K.A., Tuomanen E.I., Orme I.M., Kanneganti T.D., Bogdan C., Wynn T.A., Murray P.J. Toll-like receptor-induced arginase 1 in macrophages thwarts effective immunity against intracellular pathogens. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1399–1406. doi: 10.1038/ni.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y., Broser M., Cohen H., Bodkin M., Law K., Reibman J., Rom W.N. Enhanced interleukin-8 release and gene expression in macrophages after exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its components. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:586–592. doi: 10.1172/JCI117702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyons M.J., Yoshimura T., McMurray D.N. Interleukin (IL)-8 (CXCL8) induces cytokine expression and superoxide formation by guinea pig neutrophils infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2004;84:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elkington P.T., Friedland J.S. Matrix metalloproteinases in destructive pulmonary pathology. Thorax. 2006;61:259–266. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.051979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elkington P.T., O'Kane C.M., Friedland J.S. The paradox of matrix metalloproteinases in infectious disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;142:12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02840.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Kane C.M., Elkington P.T., Friedland J.S. Monocyte-dependent oncostatin M and TNF-alpha synergize to stimulate unopposed matrix metalloproteinase-1/3 secretion from human lung fibroblasts in tuberculosis. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1321–1330. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Kane C.M., Elkington P.T., Jones M.D., Caviedes L., Tovar M., Gilman R.H., Stamp G., Friedland J.S. STAT3, p38 MAPK, and NF-kappaB drive unopposed monocyte-dependent fibroblast MMP-1 secretion in tuberculosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:465–474. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0211OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price N.M., Gilman R.H., Uddin J., Recavarren S., Friedland J.S. Unopposed matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in human tuberculous granuloma and the role of TNF-alpha-dependent monocyte networks. J Immunol. 2003;171:5579–5586. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lasco T.M., Cassone L., Kamohara H., Yoshimura T., McMurray D.N. Evaluating the role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in experimental pulmonary tuberculosis in the guinea pig. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2005;85:245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ly L.H., McMurray D.N. The Yin-Yang of TNFalpha in the guinea pig model of tuberculosis. Indian J Exp Biol. 2009;47:432–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bekker L.G., Maartens G., Steyn L., Kaplan G. Selective increase in plasma tumor necrosis factor-alpha and concomitant clinical deterioration after initiating therapy in patients with severe tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:580–584. doi: 10.1086/517479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bezuidenhout J., Roberts T., Muller L., van Helden P., Walzl G. Pleural tuberculosis in patients with early HIV infection is associated with increased TNF-alpha expression and necrosis in granulomas. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bekker L.G., Moreira A.L., Bergtold A., Freeman S., Ryffel B., Kaplan G. Immunopathologic effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha in murine mycobacterial infection are dose dependent. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6954–6961. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6954-6961.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsenova L., Bergtold A., Freedman V.H., Young R.A., Kaplan G. Tumor necrosis factor alpha is a determinant of pathogenesis and disease progression in mycobacterial infection in the central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5657–5662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Djoba Siawaya J.F., Bapela N.B., Ronacher K., Beyers N., van Helden P., Walzl G. Differential expression of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-4 delta 2 mRNA, but not transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta): TGF-beta RII, Foxp3, gamma interferon, T-bet, or GATA-3 mRNA, in patients with fast and slow responses to antituberculosis treatment. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:1165–1170. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00084-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Condos R., Rom W.N., Liu Y.M., Schluger N.W. Local immune responses correlate with presentation and outcome in tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:729–735. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.3.9705044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manca C., Tsenova L., Freeman S., Barczak A.K., Tovey M., Murray P.J., Barry C., Kaplan G. Hypervirulent M. tuberculosis W/Beijing strains upregulate type I IFNs and increase expression of negative regulators of the Jak-Stat pathway. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:694–701. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aguilar D., Hanekom M., Mata D., Gey van Pittius N.C., van Helden P.D., Warren R.M., Hernandez-Pando R. Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains with the Beijing genotype demonstrate variability in virulence associated with transmission. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2010;90:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Redente E.F., Higgins D.M., Dwyer-Nield L.D., Orme I.M., Gonzalez-Juarrero M., Malkinson A.M. Differential polarization of alveolar macrophages and bone marrow-derived monocytes following chemically and pathogen-induced chronic lung inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:159–168. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Kane C.M., Boyle J.J., Horncastle D.E., Elkington P.T., Friedland J.S. Monocyte-dependent fibroblast CXCL8 secretion occurs in tuberculosis and limits survival of mycobacteria within macrophages. J Immunol. 2007;178:3767–3776. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kasahara K., Sato I., Ogura K., Takeuchi H., Kobayashi K., Adachi M. Expression of chemokines and induction of rapid cell death in human blood neutrophils by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:127–137. doi: 10.1086/515585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moschos C., Porfiridis I., Psallidas I., Kollintza A., Stathopoulos G.T., Papiris S.A., Roussos C., Kalomenidis I. Osteopontin is upregulated in malignant and inflammatory pleural effusions. Respirology. 2009;14:716–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Regan A.W., Hayden J.M., Body S., Liaw L., Mulligan N., Goetschkes M., Berman J.S. Abnormal pulmonary granuloma formation in osteopontin-deficient mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:2243–2247. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.12.2104139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nau G.J., Chupp G.L., Emile J.F., Jouanguy E., Berman J.S., Casanova J.L., Young R.A. Osteopontin expression correlates with clinical outcome in patients with mycobacterial infection. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:37–42. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64514-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mori R., Shaw T.J., Martin P. Molecular mechanisms linking wound inflammation and fibrosis: knockdown of osteopontin leads to rapid repair and reduced scarring. J Exp Med. 2008;205:43–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jacobsen L.C., Theilgaard-Monch K., Christensen E.I., Borregaard N. Arginase 1 is expressed in myelocytes/metamyelocytes and localized in gelatinase granules of human neutrophils. Blood. 2007;109:3084–3087. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-032599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elkington P.T., Emerson J.E., Lopez-Pascua L.D., O'Kane C.M., Horncastle D.E., Boyle J.J., Friedland J.S. Mycobacterium tuberculosis up-regulates matrix metalloproteinase-1 secretion from human airway epithelial cells via a p38 MAPK switch. J Immunol. 2005;175:5333–5340. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gill S.E., Parks W.C. Metalloproteinases and their inhibitors: regulators of wound healing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1334–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rivera-Marrero C.A., Schuyler W., Roser S., Roman J. Induction of MMP-9 mediated gelatinolytic activity in human monocytic cells by cell wall components of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microb Pathog. 2000;29:231–244. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2000.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hrabec E., Strek M., Zieba M., Kwiatkowska S., Hrabec Z. Circulation level of matrix metalloproteinase-9 is correlated with disease severity in tuberculosis patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:713–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang C.H., Lin H.C., Lin S.M., Huang C.D., Liu C.Y., Huang K.H., Hsieh L.L., Chung K.F., Kuo H.P. MMP-1(-1607G) polymorphism as a risk factor for fibrosis after pulmonary tuberculosis in Taiwan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:627–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Faveeuw C., Preece G., Ager A. Transendothelial migration of lymphocytes across high endothelial venules into lymph nodes is affected by metalloproteinases. Blood. 2001;98:688–695. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Izzo A.A., Izzo L.S., Kasimos J., Majka S. A matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor promotes granuloma formation during the early phase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis pulmonary infection. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2004;84:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elkington P.T., Green J.A., Emerson J.E., Lopez-Pascua L.D., Boyle J.J., O'Kane C.M., Friedland J.S. Synergistic up-regulation of epithelial cell matrix metalloproteinase-9 secretion in tuberculosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:431–437. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0011OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Green J.A., Elkington P.T., Pennington C.J., Roncaroli F., Dholakia S., Moores R.C., Bullen A., Porter J.C., Agranoff D., Edwards D.R., Friedland J.S. Mycobacterium tuberculosis upregulates microglial matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -3 expression and secretion via NF-kappaB- and Activator Protein-1-dependent monocyte networks. J Immunol. 2010;184:6492–6503. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parks W.C., Wilson C.L., Lopez-Boado Y.S. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:617–629. doi: 10.1038/nri1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Quiding-Jarbrink M., Smith D.A., Bancroft G.J. Production of matrix metalloproteinases in response to mycobacterial infection. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5661–5670. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5661-5670.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chang J.C., Wysocki A., Tchou-Wong K.M., Moskowitz N., Zhang Y., Rom W.N. Effect of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its components on macrophages and the release of matrix metalloproteinases. Thorax. 1996;51:306–311. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.3.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ra H.J., Parks W.C. Control of matrix metalloproteinase catalytic activity. Matrix Biol. 2007;26:587–596. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vilcheze C., Jacobs W.R., Jr. The mechanism of isoniazid killing: clarity through the scope of genetics. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:35–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.111606.122346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Flynn J.L., Goldstein M.M., Chan J., Triebold K.J., Pfeffer K., Lowenstein C.J., Schreiber R., Mak T.W., Bloom B.R. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is required in the protective immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Immunity. 1995;2:561–572. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin P.L., Plessner H.L., Voitenok N.N., Flynn J.L. Tumor necrosis factor and tuberculosis. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2007;12:22–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.jidsymp.5650027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Keane J., Gershon S., Wise R.P., Mirabile-Levens E., Kasznica J., Schwieterman W.D., Siegel J.N., Braun M.M. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1098–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Harris J., Keane J. How tumour necrosis factor blockers interfere with tuberculosis immunity. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;161:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spina D. PDE4 inhibitors: current status. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:308–315. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]